Coupled Chiral Optical Tamm States in Cholesteric Liquid Crystals

Abstract

1. Introduction

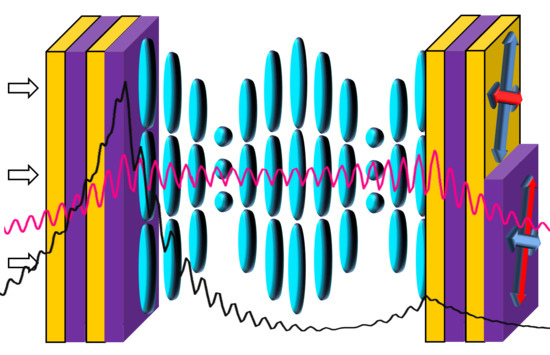

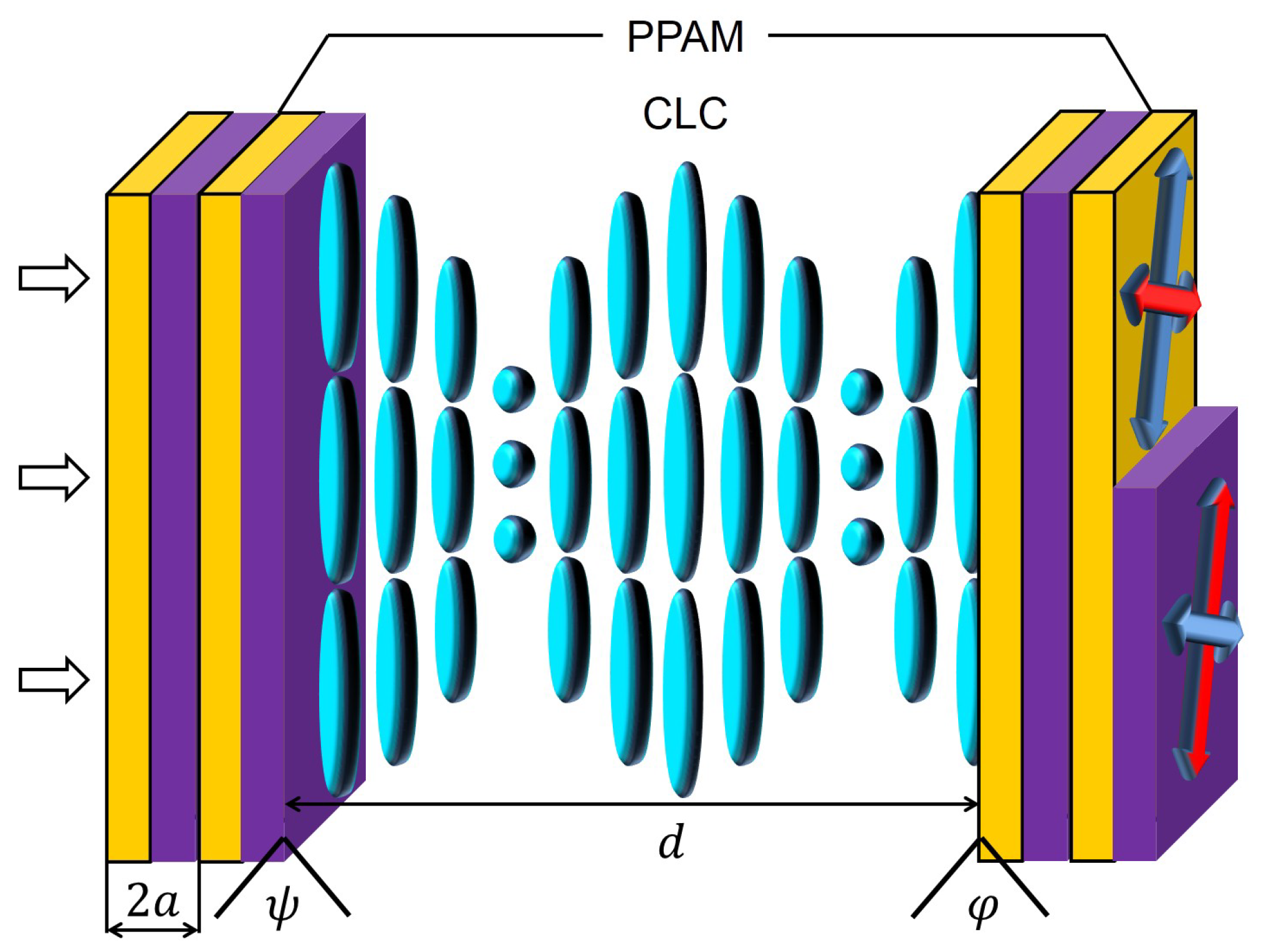

2. Model Description

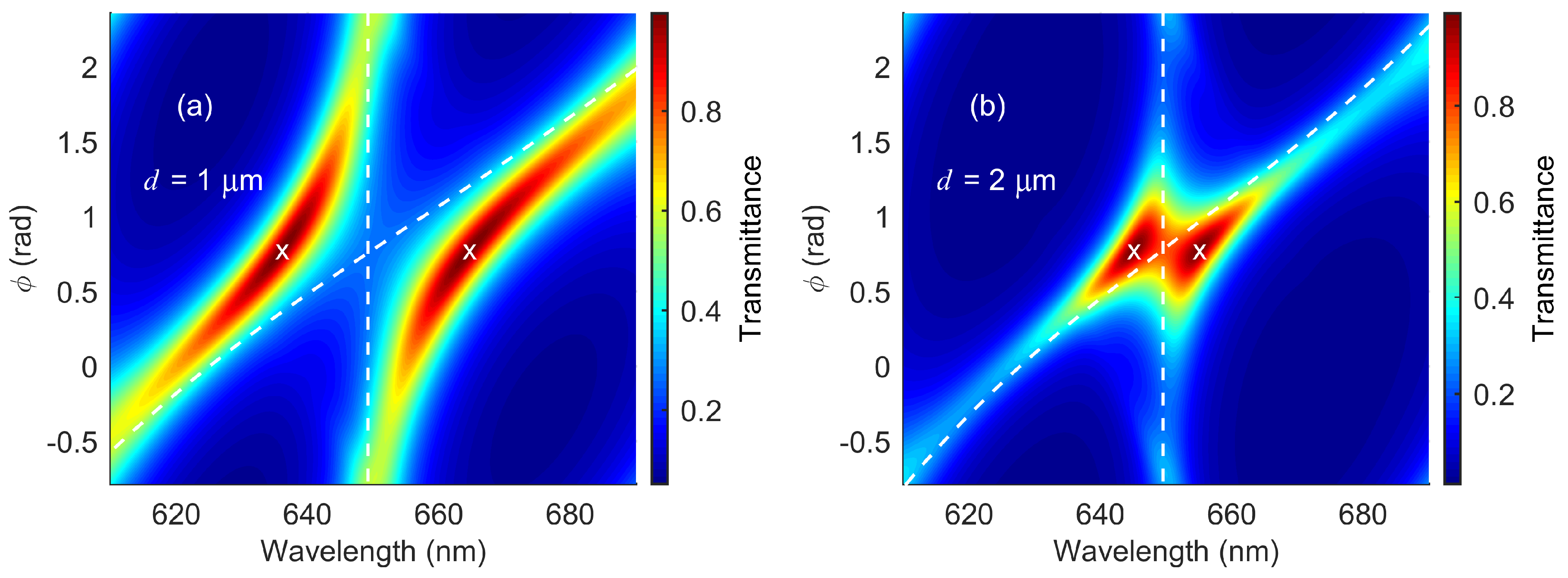

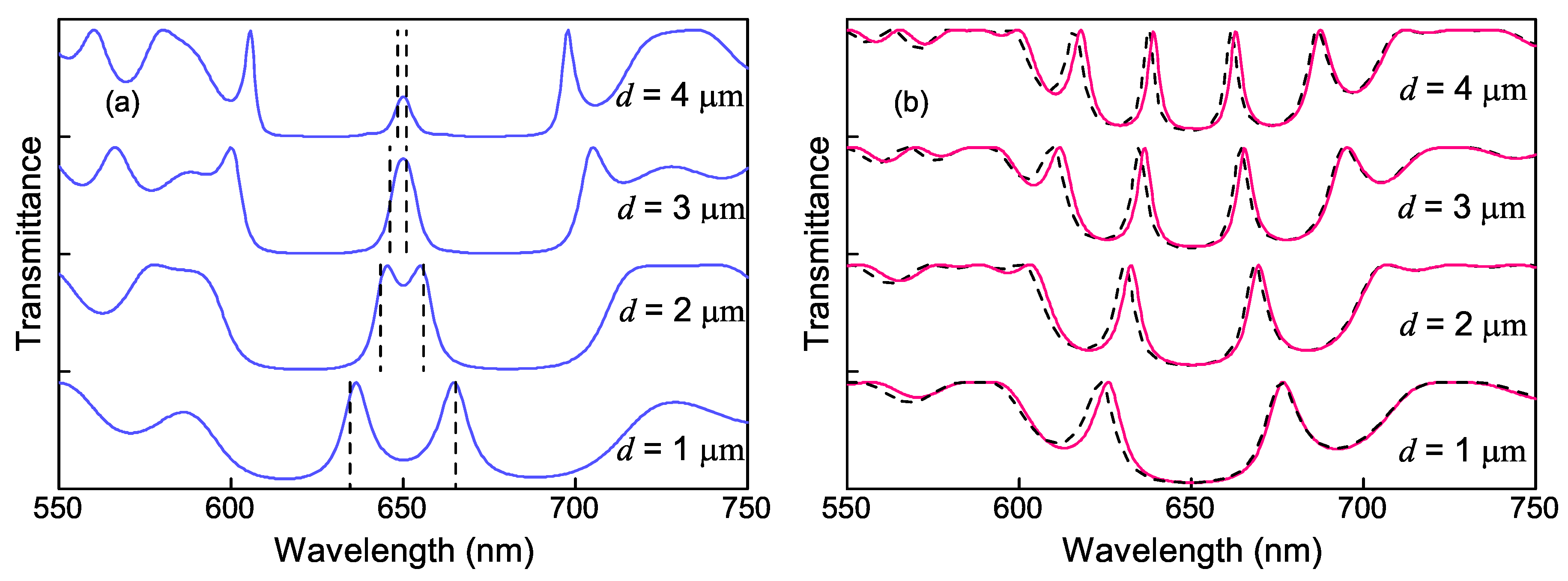

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Goto, T.; Dorofeenko, A.V.; Merzlikin, A.M.; Baryshev, A.V.; Vinogradov, A.P.; Inoue, M.; Lisyansky, A.A.; Granovsky, A.B. Optical Tamm states in one-dimensional magnetophotonic structures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 101, 113902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kavokin, A.V.; Shelykh, I.A.; Malpuech, G. Lossless interface modes at the boundary between two periodic dielectric structures. Phys. Rev. B 2005, 72, 233102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinogradov, A.P.; Dorofeenko, A.V.; Merzlikin, A.M.; Lisyansky, A.A. Surface states in photonic crystals. Phys. Uspekhi 2010, 53, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaliteevski, M.A.; Iorsh, I.; Brand, S.; Abram, R.A.; Chamberlain, J.M.; Kavokin, A.V.; Shelykh, I.A. Tamm plasmon-polaritons: Possible electromagnetic states at the interface of a metal and a dielectric Bragg mirror. Phys. Rev. B 2007, 76, 165415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symonds, C.; Lheureux, G.; Hugonin, J.-P.; Greffet, J.-J.; Laverdant, J.; Brucoli, G.; Lemaitre, A.; Senellart, P.; Bellessa, J. Confined Tamm plasmon lasers. Nano Lett. 2013, 13, 3179–3184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez-Solano, A.; Galisteo-López, J.F.; Míguez, H. Flexible and adaptable light-emitting coatings for arbitrary metal surfaces based on optical tamm mode coupling. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2017, 6, 1700560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.-Y.; Ishii, S.; Yokoyama, T.; Dao, T.D.; Sun, M.-G.; Pankin, P.S.; Timofeev, I.V.; Nagao, T.; Chen, K.-P. Narrowband wavelength selective thermal emitters by confined tamm plasmon polaritons. ACS Photonics 2017, 4, 2212–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.-L.; Feng, J.; Han, X.-C.; Liu, Y.-F.; Chen, Q.-D.; Song, J.-F.; Sun, H.-B. Hybrid Tamm plasmon-polariton/microcavity modes for white top-emitting organic light-emitting devices. Optica 2015, 2, 579–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.-G.; Chen, K.-P.; Jeng, S.-C. Phase sensitive sensor on Tamm plasmon devicess. Opt. Mater. Express 2017, 72, 1267–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Maji, P.S.; Das, R. Tamm-plasmon resonance based temperature sensor in a Ta2O5/SiO2 based distributed Bragg reflector. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2017, 260, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.-L.; Song, J.-F.; Li, X.-B.; Feng, J.; Sun, H.-B. Optical Tamm states enhanced broad-band absorption of organic solar cells. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2012, 101, 243901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.-C.; Kuo, C.-Y.; Hung, Y.-J.; Chen, K.-P.; Jeng, S.-C. Liquid-crystal active tamm-plasmon devices. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2018, 9, 064034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaliteevski, M.; Brand, S.; Abram, R.A.; Iorsh, I.; Kavokin, A.V.; Shelykh, I.A. Hybrid states of Tamm plasmons and exciton polaritons. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2009, 95, 251108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.K.S.-U.; Klein, T.; Klembt, S.; Gutowski, J.; Hommel, D.; Sebald, K. Observation of a hybrid state of Tamm plasmons and microcavity exciton polaritons. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 34392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afinogenov, B.I.; Bessonov, V.O.; Nikulin, A.A.; Fedyanin, A.A. Observation of hybrid state of Tamm and surface plasmon-polaritons in one-dimensional photonic crystals. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2013, 103, 061112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetrov, S.Ya.; Bikbaev, R.G.; Timofeev, I.V. Optical Tamm states at the interface between a photonic crystal and a nanocomposite with resonance dispersion. J. Exp. Theor. Phys. 2013, 117, 988–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pankin, P.S.; Vetrov, S.Ya.; Timofeev, I.V. Tunable hybrid Tamm-microcavity states. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B: Opt. Phys. 2017, 34, 2633–2639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blinov, L.M. Structure and Properties of Liquid Crystals; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2011; ISBN 978-90-481-8829-1. [Google Scholar]

- Vetrov, S.Y.; Pyatnov, M.V.; Timofeev, I.V. Surface modes in “photonic cholesteric liquid crystal—Phase plate—Metal” structure. Opt. Lett. 2014, 39, 2743–2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vetrov, S.Ya.; Pyatnov, M.V.; Timofeev, I.V. Spectral and polarization properties of a ‘cholesteric liquid crystal—Phase plate—Metal’structure. J. Opt. 2015, 18, 015103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyatnov, M.V.; Vetrov, S.Ya.; Timofeev, I.V. Localised optical states in a structure formed by two oppositely handed cholesteric liquid crystal layers and a metal. Liq. Cryst. 2017, 44, 674–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyatnov, M.V.; Vetrov, S.Ya.; Timofeev, I.V. Localized optical modes in a defect-containing liquid-crystal structure adjacent to the metal. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B: Opt. Phys. 2017, 34, 2011–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timofeev, I.V.; Vetrov, S.Ya. Chiral optical Tamm states at the boundary of the medium with helical symmetry of the dielectric tensor. JETP Lett. 2016, 104, 380–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timofeev, I.V.; Pankin, P.S.; Vetrov, S.Ya.; Arkhipkin, V.G.; Lee, W.; Zyryanov, V.Ya. Chiral optical Tamm states: Temporal coupled-mode theory. Crystals 2017, 7, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, F.; Wang, Z.; He, S.; Shalaev, V.M.; Kildishev, A.V. Broadband high-efficiency half-wave plate: A supercell-based plasmonic metasurface approach. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 4111–4119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuhisa, Y.; Ozaki, R.; Yoshino, K.; Ozaki, M. High Q defect mode and laser action in one-dimensional hybrid photonic crystal containing cholesteric liquid crystal. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2006, 89, 101109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudakova, N.V.; Timofeev, I.V.; Pankin, P.S.; Vetrov, S.Y. Polarization-preserving anisotropic mirror on the basis of metal–dielectric nanocomposite. Bull. Russ. Acad. Sci. Phys. 2017, 81, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudakova, N.V.; Timofeev, I.V.; Bikbaev, R.G.; Pyatnov, M.V.; Vetrov, S.Ya.; Lee, W. Chiral Optical Tamm states at the interface between a cholesteric and an all-dielectric polarization-preserving anisotropic mirror. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1808.06243. [Google Scholar]

- Berreman, D.W. Optics in stratified and anisotropic media: 4 × 4-matrix formulation. J. Opt. Soc. Am. 1972, 62, 502–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belyakov, V.A.; Semenov, S.V. Optical defect modes in chiral liquid crystals. J. Exp. Teor. Phys. 2011, 112, 694–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avendano, C.G.; Ponti, S.; Reyes, J.A.; Oldano, C. Multiplet structure of the defect modes in 1D helical photonic crystals with twist defects. J. Phys. A Math. Gen. 2005, 38, 8821–8840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iorsh, I.; Panicheva, P.V.; Slovinskii, I.A.; Kaliteevski, M.A. Coupled Tamm plasmons. Tech. Phys. Lett. 2012, 38, 351–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belyakov, V.A. Diffraction Optics of Complex-Structured Periodic Media; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1992; ISBN 978-1-4612-4396-0. [Google Scholar]

- Yariv, A.; Yeh, P. Optical Waves in Crystals; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1984; ISBN-13: 978-0471430810, ISBN-10: 0471430811. [Google Scholar]

- Haus, H.A. Waves and Fields in Optoelectronics; Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1984; ISBN-13: 9780139460531, ISBN-10: 0139460535. [Google Scholar]

- Dolganov, P.V.; Gordeev, S.O.; Dolganov, V.K.; Bobrovsky, A.Y. Photo- and thermo-induced variation of photonic properties of cholesteric liquid crystal containing azobenzene-based chiral dopant. Mol. Cryst. Liq. Cryst. 2016, 633, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Z.; Patel, J.S. Behavior of cholesteric liquid crystals in a Fabry-Perot cavity. Opt. Lett. 1999, 24, 1759–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdulhalim, I. Unique optical properties of anisotropic helical structures in a Fabry-Perot cavity. Opt. Lett. 1999, 31, 3019–3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pyatnov, M.V.; Timofeev, I.V.; Vetrov, S.Y.; Rudakova, N.V. Coupled Chiral Optical Tamm States in Cholesteric Liquid Crystals. Photonics 2018, 5, 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics5040030

Pyatnov MV, Timofeev IV, Vetrov SY, Rudakova NV. Coupled Chiral Optical Tamm States in Cholesteric Liquid Crystals. Photonics. 2018; 5(4):30. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics5040030

Chicago/Turabian StylePyatnov, Maxim V., Ivan V. Timofeev, Stepan Ya. Vetrov, and Natalya V. Rudakova. 2018. "Coupled Chiral Optical Tamm States in Cholesteric Liquid Crystals" Photonics 5, no. 4: 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics5040030

APA StylePyatnov, M. V., Timofeev, I. V., Vetrov, S. Y., & Rudakova, N. V. (2018). Coupled Chiral Optical Tamm States in Cholesteric Liquid Crystals. Photonics, 5(4), 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics5040030