Minimal Perturbation Engineering for Programmable Optical Skyrmions on Metasurfaces

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Analysis

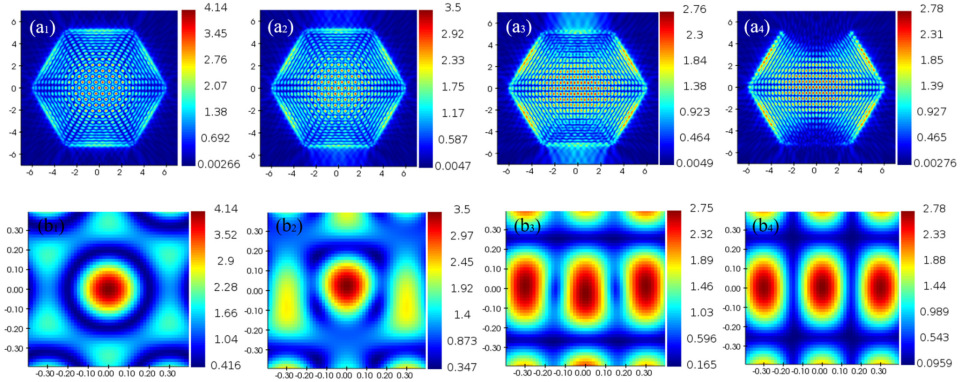

3. Results and Discussion

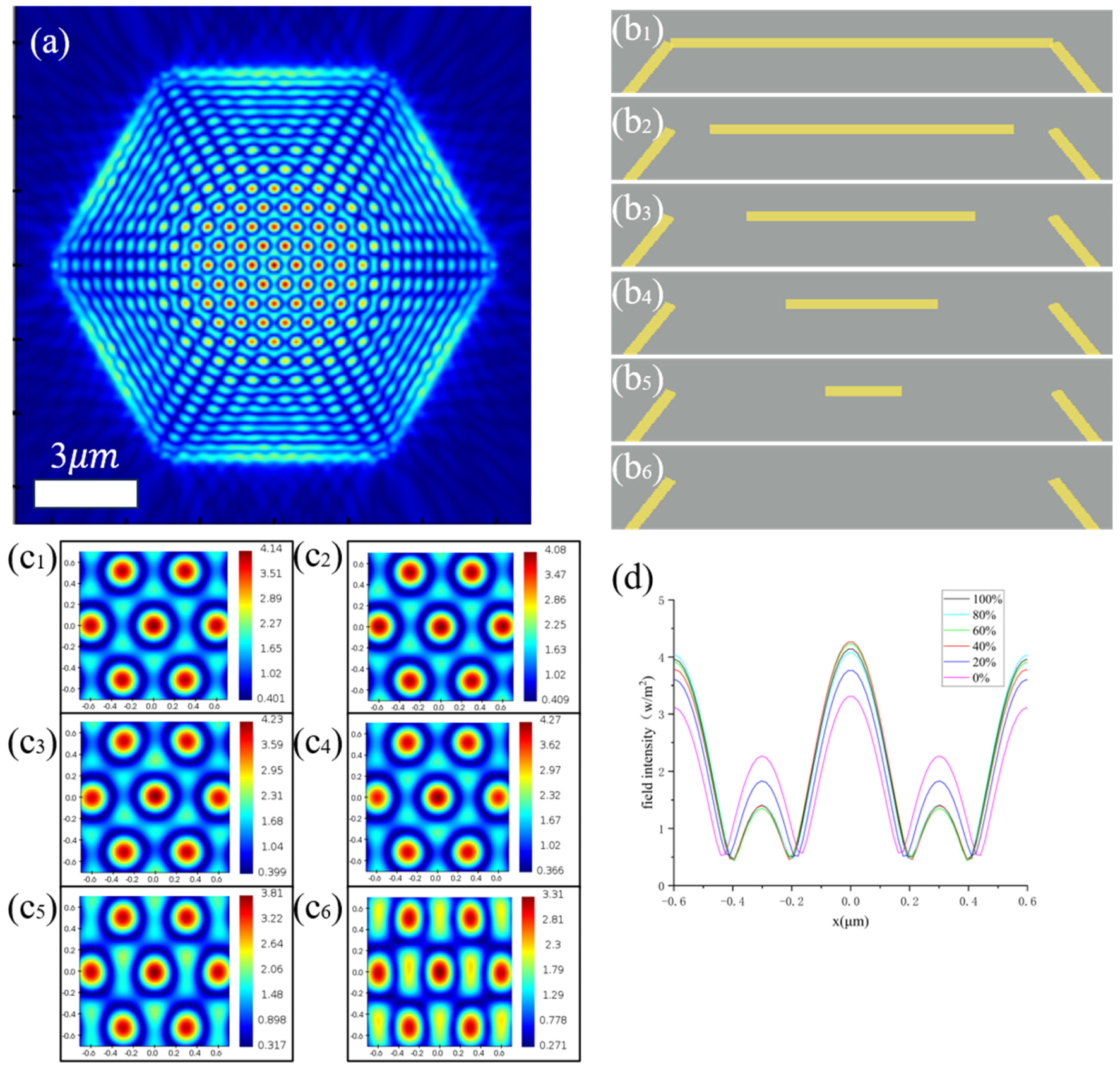

3.1. Intensity of Periodic Optical Lattice with Slit Perturbation Structure

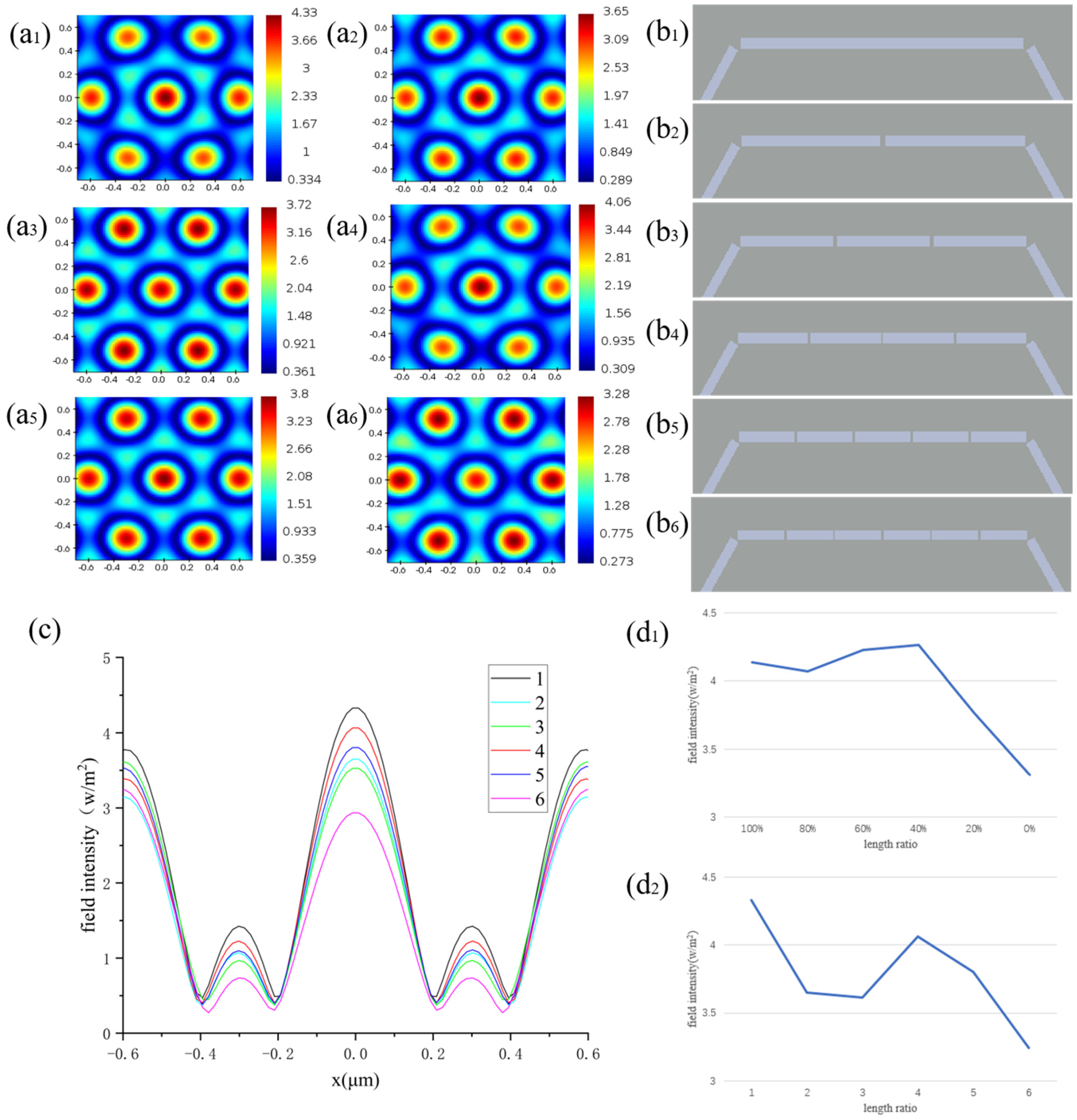

3.2. Polarization Perturbation Structure Period Optical Lattice Intensity

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Skyrme, T.H.R. A unified field theory of mesons and baryons. Nucl. Phys. 1962, 31, 556–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rössler, U.K.; Bogdanov, A.N.; Pfleiderer, C. Spontaneous skyrmion ground states in magnetic metals. Nature 2006, 442, 797–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, A.K.; Kumar, V.; Ma, T.P. Magnetic antiskyrmions above room temperature in tetragonal Heusler materials. Nature 2017, 548, 561–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J.E. The birth of topological insulators. Nature 2010, 464, 194–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mühlbauer, S. Skyrmion lattice in a chiral magnet (February, pg 915, 2009). Science 2011, 333, 1381. [Google Scholar]

- Al Khawaja, U.; Stoof, H.T.C. Skyrmion physics in Bose-Einstein ferromagnets—Art. no. 043612. Phys. Rev. A 2001, 64, 043612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, J.; Zumer, S. Quasi-two-dimensional Skyrmion lattices in a chiral nematic liquid crystal. Nat. Commun. 2011, 2, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolas, A.; Veissier, L.; Giner, L. A quantum memory for orbital angular momentum photonic qubits. Nat. Photonics 2014, 8, 234–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Xu, B.W.; Zhong, W. Device-Independent Quantum Secure Direct Communication with Single-Photon. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2023, 19, 014036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romming, N.; Hanneken, C.; Menzel, M. Writing and Deleting Single Magnetic Skyrmions. Science 2013, 341, 636–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maccariello, D.; Legrand, W.; Reyren, N. Electrical detection of single magnetic skyrmions in metallic multilayers at room temperature. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2018, 13, 233–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fert, A.; Cros, V.; Sampaio, J. Skyrmions on the track. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2013, 8, 152–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaosa, N.; Tokura, Y. Topological properties and dynamics of magnetic skyrmions. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2013, 8, 899–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kedia, H.; Foster, D.; Dennis, M.R. Weaving Knotted Vector Fields with Tunable Helicity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016, 117, 274501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, X.R.; Yang, A.P.; Shi, P. Photonic Spin Lattices: Symmetry Constraints for Skyrmion and Meron Topologies. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2021, 127, 237403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, L.P.; Yang, A.P.; Zayats, A.V. Deep-subwavelength features of photonic skyrmions in a confined electromagnetic field with orbital angular momentum. Nat. Phys. 2019, 15, 650–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Cao, R.X.; Miao, B.F. Creating an Artificial Two-Dimensional Skyrmion Crystal by Nanopatterning. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2013, 110, 167201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, D.A.; Maranville, B.B.; Balk, A.L. Realization of ground-state artificial skyrmion lattices at room temperature. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafezi, M.; Mittal, S.; Fan, J. Imaging topological edge states in silicon photonics. Nat. Photonics 2013, 7, 1001–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, W.M.; Ren, Z.C.; Wang, X.L. Polarization structure transition of C-point singularities upon reflection. Sci. China-Phys. Mech. Astron. 2025, 68, 244211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.R.; Yang, H.H.; Cao, Y.S. Photonic orbital angular momentum transfer and magnetic skyrmion rotation. Opt. Express 2018, 26, 8778–8790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.W.; Beg, M.; Zhang, B. Driving magnetic skyrmions with microwave fields. Phys. Rev. B 2015, 92, 020403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spektor, G.; Prinz, E.; Hartelt, M. Orbital angular momentum multiplication in plasmonic vortex cavities. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabg5571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spektor, G.; Kilbane, D.; Mahro, K. Revealing the subfemtosecond dynamics of orbital angular momentum in nanoplasmonic vortices. Science 2017, 355, 1187–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, K.J.; Yu, Z.F.; Fan, S.H. Realizing effective magnetic field for photons by controlling the phase of dynamic modulation. Nat. Photonics 2012, 6, 782–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.B.; Hesselink, L.; Liu, Z.W. Large positive and negative lateral optical beam displacements due to surface plasmon resonance. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2004, 85, 372–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Xiao, X.; Hu, C. Broadband Surface Plasmon Polariton Directional Coupling via Asymmetric Optical Slot Nanoantenna Pair. Nano Lett. 2014, 14, 704–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.L.; Song, X.W.; Ji, B.Y. Demonstrating a two-dimensional-tunable surface plasmon polariton dispersion element using photoemission electron microscopy. Opt. Lett. 2019, 44, 2935–2938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.M.; Qin, Y.L.; Lang, P. Investigation of a dual-hole structure-based broadband femtosecond nondiffracting SPP beam emitter by photoemission electron microscopy. Opt. Laser Technol. 2022, 146, 107538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Mechelen, T.; Jacob, Z. Universal spin-momentum locking of evanescent waves. Optica 2016, 3, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bliokh, K.Y.; Nori, F. Transverse and longitudinal angular momenta of light. Phys. Rep.-Rev. Sec. Phys. Lett. 2015, 592, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.H.; Suh, W.; Joannopoulos, J.D. Temporal coupled-mode theory for the Fano resonance in optical resonators. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A-Opt. Image Sci. Vis. 2003, 20, 569–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bliokh, K.Y.; Nori, F. Characterizing optical chirality. Phys. Rev. A 2011, 83, 021803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meiler, T.; Frank, B.; Giessen, H. Dynamic tailoring of an optical skyrmion lattice in surface plasmon polaritons: Comment. Opt. Express 2020, 28, 33614–33615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.Y.; Ji, B.Y.; Lang, P. Impact of the geometry of the excitation structure on optical skyrmion. Opt. Express 2023, 31, 37929–37942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, P.B.; Christy, R.W. Optical Constants of the Noble Metals. Phys. Rev. B 1972, 6, 4370–4379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, T.J.; Janoschka, D.; Dreher, P. Ultrafast vector imaging of plasmonic skyrmion dynamics with deep subwavelength resolution. Science 2020, 368, eaba6415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Liu, Q.; Duan, H.G. Wavelength-tuned transformation between photonic skyrmion and meron spin textures. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2024, 11, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| proportion of full length | 100% | 80% | 60% | 40% | 20% | 0% |

| 4.137 | 4.071 | 4.229 | 4.262 | 3.764 | 3.309 | |

| variation | / | −1.6% | +2.2% | +3.0% | −9.0% | −20.0% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, Z.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, D. Minimal Perturbation Engineering for Programmable Optical Skyrmions on Metasurfaces. Photonics 2025, 12, 1170. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics12121170

Zhao Z, Wang Q, Zhang D. Minimal Perturbation Engineering for Programmable Optical Skyrmions on Metasurfaces. Photonics. 2025; 12(12):1170. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics12121170

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Zhening, Qi Wang, and Dawei Zhang. 2025. "Minimal Perturbation Engineering for Programmable Optical Skyrmions on Metasurfaces" Photonics 12, no. 12: 1170. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics12121170

APA StyleZhao, Z., Wang, Q., & Zhang, D. (2025). Minimal Perturbation Engineering for Programmable Optical Skyrmions on Metasurfaces. Photonics, 12(12), 1170. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics12121170