1. Introduction

Understanding molecular geometry is essential for elucidating chemical structure and bonding. In particular, the presence of specific bonds, such as N–H and C=O, plays a fundamental role in biological processes [

1]. These bonds influence molecular size, shape, and reactivity, making accurate determination of bond lengths crucial.

Bond length, defined as the distance between the nuclei of two covalently bonded atoms, underpins much of modern chemistry. Experimental determination of bond lengths at the atomic scale remains challenging, with historical data being relatively scarce. Before 1987, most experimental bond-length measurements were obtained via X-ray and neutron diffraction, microwave spectroscopy, and electron diffraction; for a comprehensive compilation of these early data, see Allen et al. [

2]. More recent technological advances have enabled alternative techniques, for instance, Khalaji et al. [

3].

The theoretical investigation of bond lengths dates back to the early 20th century. As early as 1920, Wyckoff and Huggins investigated bond length data in relation to covalent radii, highlighting both the effectiveness and the inherent limitations of the approach [

4]. A detailed historical overview is provided by Pauling [

5], who proposed a quantitative relationship between bond length and bond order. In Pauling’s formulation, bond order is defined as the ratio of the total number of bonds to the number of bond groups, yielding remarkably accurate predictions of bond lengths. The following two models, originally presented by Pauling [

6] and Coulson [

7], remain widely used:

where

and

are the single- and double-bond lengths, respectively,

F is the force constant ratio, and

is the Pauling bond order. Typical parameter values are

Å,

Å, and

.

where

s and

d denote single- and double-bond lengths,

and

their force constants (typically

and

dyn/cm, respectively), and

the Coulson bond order.

In 1941, Schomaker and Stevenson introduced an empirical formula based on electronegativity differences [

8]:

where

and

are covalent radii in picometers,

and

their electronegativities, and

pm. While Equation (

3) generally agrees with experiments, it relies heavily on a single fluorine radius and does not consider other bonding factors.

Numerous experimental studies have investigated bond lengths in biologically and chemically significant molecules. For instance, Harsasius examined the geometry of uracil and its methylated derivatives, while Rossi analyzed the crystal structure of quercetin [

9]. Despite this extensive data, several semi-empirical methods (e.g., MINDO/2, CNDO/2, STO-3G) have been criticized for their limited accuracy [

1]. As a result, theoretical approaches that correlate bond lengths with molecular properties such as electronegativity, covalent radii, and bond order have gained increasing attention [

10,

11].

Density Functional Theory (DFT) has emerged as the standard method for predicting molecular bond lengths, typically achieving accuracies within 0.01–0.02 of experimental values for organic compounds. Another widely used approach is the parametric method 6, a semi-empirical quantum-chemical method commonly applied for bond length optimization and molecular geometry evaluation. Although both methods provides high accuracy, they remain computationally intensive for larger molecular systems. Consequently, while DFT is preferred when sufficient computational resources are available, graph theoretic approaches offer a computationally efficient alternative that retains chemical interpretability.

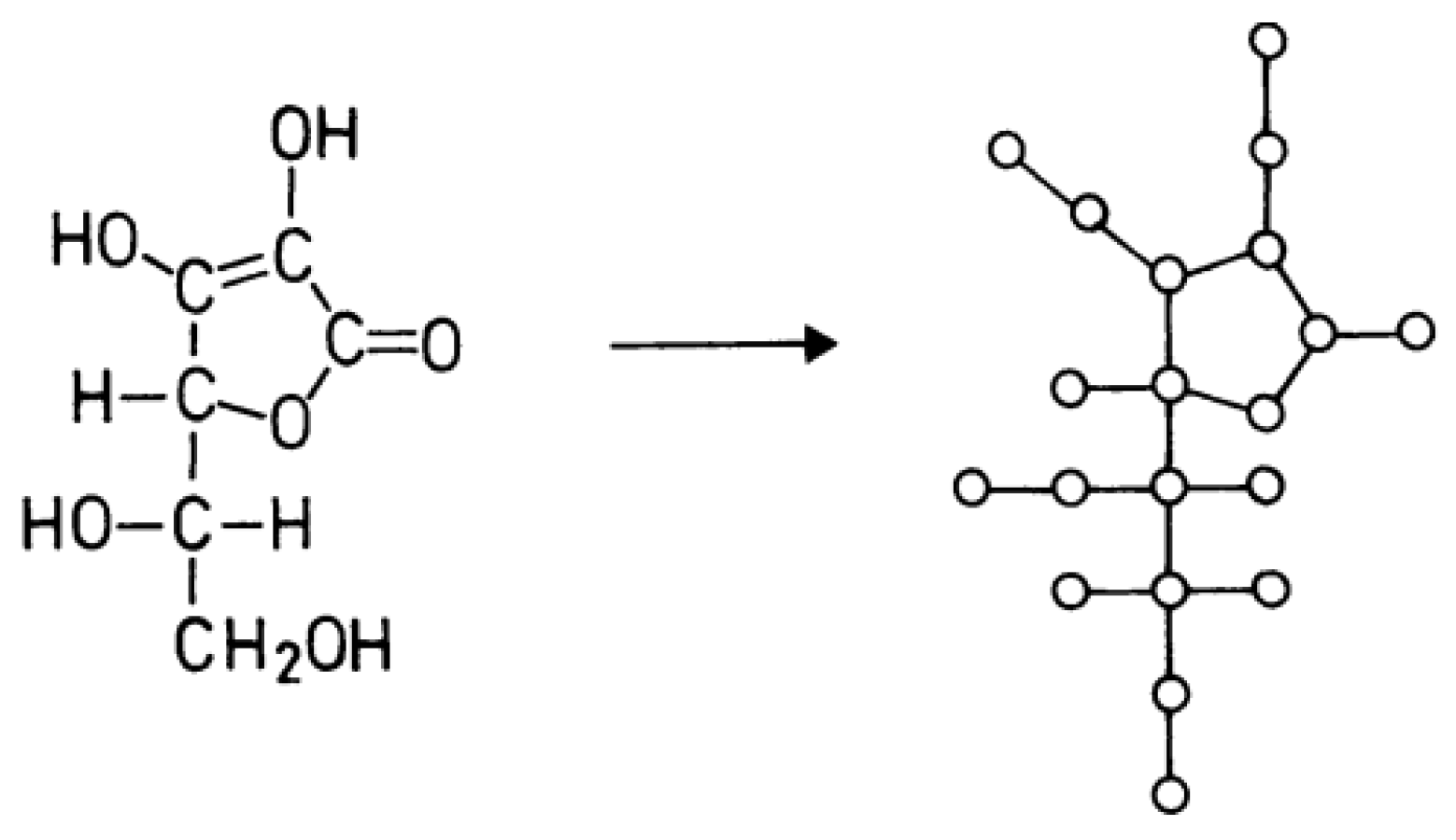

More recently, the application of graph theory to chemical structures has offered new insights. In this framework, atoms are represented as vertices and covalent bonds as edges, allowing the use of topological indices to predict molecular geometry and reactivity.

The graphical representation of a compound is frequently referred to as a

or

. See, for example,

Figure 1.

The depiction of chemical compounds through molecular graphs, first proposed by Sir Arthur Cayley in 1874 [

13], serves as the primary application of graph theory in the field of chemistry. This depiction connects physical characteristics and biological functions with the analogues.

In this study, we are concerned with predicting the bond length of the chemical compound in the group of flavonoids called luteolin with the experimental

X-ray bond length data presented by Cox et al. in [

14]. In this study, we use graph theory, a branch of mathematics, to create a multi-variable model to predict the bond lengths between atoms in the chemical compound luteolin. We use the parameters with a high correlation with the bond length to develop the mathematical model, and the model provides an alternative means of predicting bond lengths without conducting experiments.

This paper is organized as follows: The subsequent section introduces the graph theoretic parameters.

Section 3 details the methodology employed, and the effectiveness and applicability of the model are evaluated in

Section 4. Finally,

Section 5 presents the conclusion and discussion of this paper.

2. Graph and Chemical Parameters

This section outlines the fundamental graph-theoretical and chemical parameters employed in the development of the proposed models.

A graph is a mathematical structure comprising a finite set of vertices V and a set of edges E, where each edge is a two-element subset of V. The degree of a vertex v, denoted , is the number of edges incident to v. The distance between two vertices u and v, written as , is defined as the length of the shortest path connecting u and v in G. The eccentricity of a vertex v, denoted , is the greatest distance from v to any other vertex in the graph.

A vertex u is said to be a neighbor of vertex v if there exists an edge between them, and the set of all such neighbors is called the neighborhood of v, denoted by . More generally, the neighborhood, , refers to the set of all vertices at a distance of at most k from v.

The

atomic radius of an atom

is defined as the minimum distance between its nucleus and outermost electron shell. The

covalent radius of an atom

is defined as half the distance between the nuclei of two identical atoms bonded together covalently. Data for covalent radius was obtained from WebElements, maintained by Mark Winter at the University of Sheffield (UK) [

15]. For a bond between atoms

and

, we define

as the sum of their covalent radii.

Electronegativity,

, refers to an atom’s tendency to attract bonding electrons in a covalent bond. Pauling’s electronegativity was used in this research, and the data were obtained from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) website [

16]. For atoms

and

forming a bond, we define:

- (i)

, the product of their electronegativities,

- (ii)

, the sum of weighted eccentricities,

- (iii)

, the product of weighted eccentricities.

Here, the term weighted eccentricity is defined as the product of an atom’s eccentricity in the chemical graph and its electronegativity.

Valency describes an atom’s bonding capacity and is the number of electrons it must gain or lose to achieve a stable configuration. For simplicity, a single bond is denoted by 1, a double bond by 2, and a triple bond by 3. We define a valency-based parameter which helps identify bond types (single, double, or triple bonds), where represents the bond order, taking values of or 3.

We also introduce kth-neighborhood-based descriptors:

- (i)

, the weighted kth neighborhood of the edge with respect to electronegativity,

- (ii)

, the weighted kth neighborhood of the edge with respect covalent radii.

3. Methodology and Model Development

3.1. Model Quality Assessment

The reliability and predictive performance of the proposed multiple linear regression (MLR) models are typically assessed using a combination of statistical measures and diagnostic checks. One of the fundamental indicators is the coefficient of determination (

), which represents the proportion of variance in the dependent variable that is explained by the independent variables in the model. The

value ranges from 0 to 1 and is calculated using the following formula:

where

represents the residual sum of squares and

denotes the total sum of squares. An

value close to 1 indicates a strong explanatory power, while values near 0 suggest limited predictive capability. However, since

can increase with the addition of more predictors, even if they are not meaningful, the adjusted

is also used to penalize model complexity and provide a more robust measure of model fit. Additional metrics such as the root mean square error (RMSE), mean absolute error (MAE), and standard error of the estimate are employed to offer further insight into the model’s accuracy by quantifying the average magnitude of prediction errors. In the model development, multicollinearity among predictors is examined using the correlation matrix and the variance inflation factor (VIF), with high VIF values indicating redundancy that may compromise coefficient estimates.

Residual analysis is also performed to check for homoscedasticity (constant variance of errors), linearity, independence, and normality of residuals. Graphical tools such as residual versus fitted values plots, residuals versus the explanatory variables plots, Q-Q plots, and histogram of the residuals plots are employed to identify potential violations of assumptions or influential data points that may distort the model.

3.2. Model Development

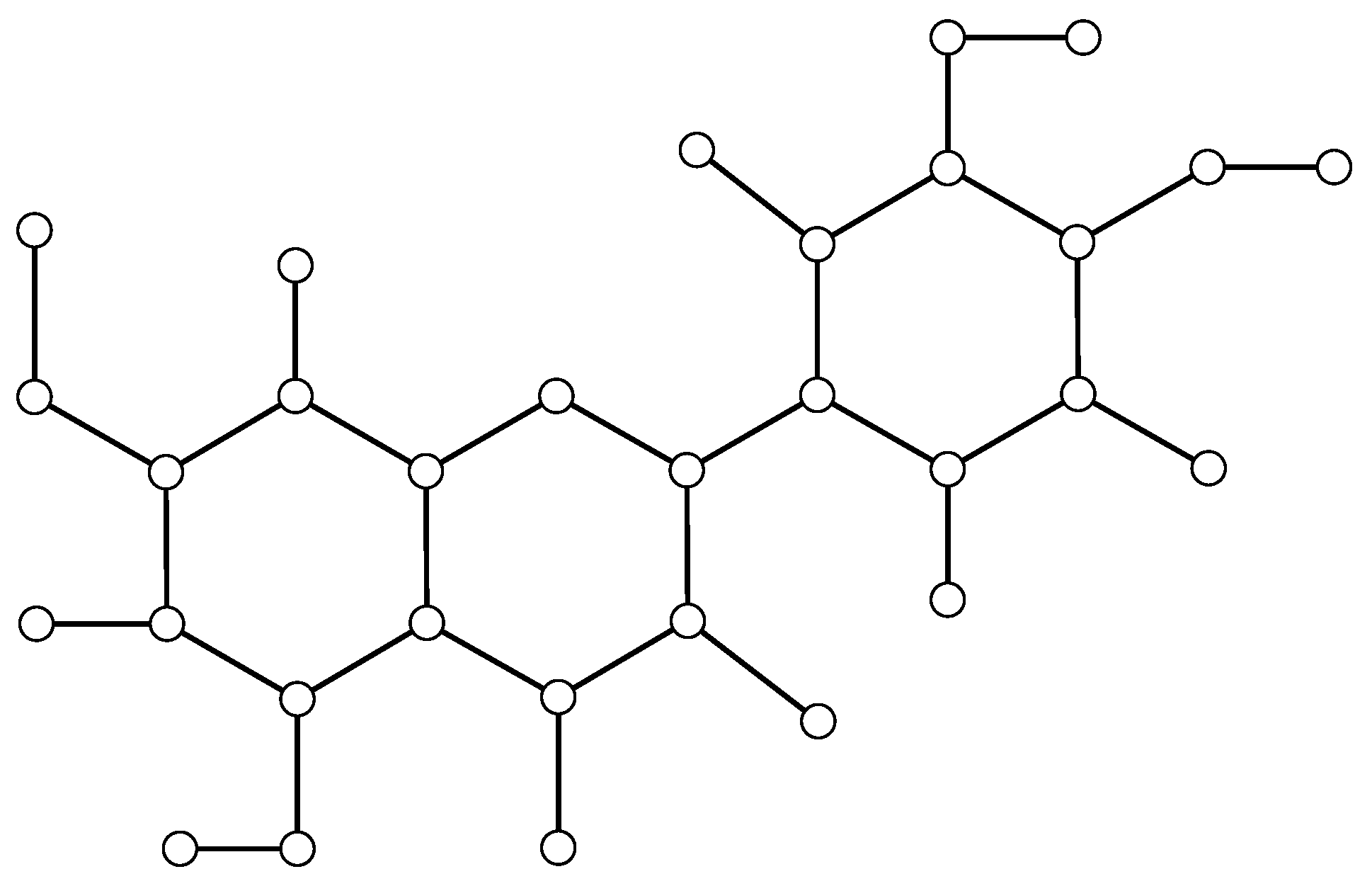

We present two models and compare their predictions. Consider a naturally occurring compound, luteolin, whose molecular structure is shown in

Figure 2 with carbon atoms numbered in black, hydrogen atoms numbered in blue, and oxygen atoms numbered in red.

The molecular graph corresponding to the structure of luteolin is illustrated in

Figure 3.

The general observation from correlation analysis is that bond length is highly correlated with the sum of the covalent radii of the atoms making up a bond, the weighted second neighborhood, and their respective reciprocals, which is summarized in

Table 1 below.

Having first quantified the correlations between the dependent variable and each predictor, we then examine the interrelationships among the independent variables by constructing a correlation matrix and presenting it as a heat map shown in

Figure 4.

From the correlation heat map, several predictors exhibit strong correlations, indicating a risk of multicollinearity and potential overfitting if all are retained. To address this, we performed a backwards-elimination procedure, iteratively removing the least significant variables until only those with p-values below (as reported under “” in the stepwise regression output) remained in the final model.

The dataset provided by Cox [

14] is employed to estimate the constant parameters of the proposed multiple linear regression model. To evaluate the model’s predictive performance; data from the edges

,

,

,

,

, and

7 are excluded during the model development phase. The selected data represent both bonds located on the molecular rings and those located outside the rings equally. These withheld data points are subsequently used to test the model’s ability to generalize to unseen cases.

Two predictive models were developed to achieve a coefficient of determination () as close to 1 as possible. Model 1 was constructed using standard linear regression techniques, while Model 2 employed a domain-specific approach by partitioning the compound into two distinct structural regions and applying the Cobb–Douglas production function to each. The performance of both models was assessed by evaluating their predictive accuracy on a subset of edges excluded from the training dataset.

3.2.1. Model 1

We begin by representing the compound as a molecular graph, as illustrated in

Figure 3, and we formulate a multi-variable linear regression model of the following form:

where:

- (a)

Y denotes the bond length (dependent variable),

- (b)

are the independent variables (molecular descriptors),

- (c)

are the regression coefficients to be estimated,

- (d)

represents the error term.

To identify the most relevant predictors and mitigate multicollinearity, a backward elimination procedure was applied in conjunction with stepwise regression. This process yielded a reduced and optimized model of the following form:

where:

- (a)

Y is the bond length,

- (b)

is a valency-based parameter,

- (c)

is the sum of the covalent radii of the atoms forming the bond,

- (d)

is the weighted second neighborhood descriptor.

After removing statistically insignificant variables, we calculated the variance inflation factors (VIFs) for the remaining predictors. The results, shown in

Table 2, indicate low multicollinearity among the variables.

The final regression model demonstrates strong explanatory power with:

Moreover, the OLS diagnostics presented in

Table 3 confirm the model’s overall statistical significance and robustness.

Table 3.

Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression results.

Table 3.

Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression results.

| | Coefficient | Std. Error | t-Statistic | p-Value | CI Lower (0.025) | CI Upper (0.975) |

|---|

| valency parameter, | 0.0761 | 0.021 | 3.6213 | 0.0014 | 0.0326 | 0.1195 |

| 1/(r1 + r2) | −1.85 | 0.0715 | −25.8593 | 0.0 | −1.998 | −1.702 |

| weighted 2nd Nbd, | 0.0053 | 0.0012 | 4.2483 | 0.0003 | 0.0027 | 0.0078 |

| const | 2.3833 | 0.0782 | 30.4674 | 0.0 | 2.2214 | 2.5451 |

| Model Statistics |

| R-squared | 0.9898 |

| Adj. R-squared | 0.9884 |

| F-statistic | 742.56 |

| Prob (F-statistic) | 5.0439 × 10−23 |

| Log-Likelihood | 65.947 |

| AIC | −123.894 |

| BIC | −118.71 |

The model exhibits a high degree of explanatory power, with an value of 0.9898 and an adjusted of 0.9884, indicating that 99% of the variability in bond length is accounted for by the predictors. The F-statistic of 742.6 with a p-value less than confirms the overall significance of the model.

All three predictors were found to be statistically significant at the 1% level. The coefficient for the valency parameter, , which is the reciprocal of the bond order, is positive (, ). This positive coefficient indicates that as the bond order increases, the valency parameter decreases, leading to a decrease in predicted bond length. This aligns with fundamental chemical principles, where higher bond orders correspond to stronger, shorter bonds. Thus, the model correctly captures the expected inverse relationship between bond order and bond length.

The inverse sum of covalent radii exhibits a strong negative association with bond length (, ), aligning well with chemical intuition that larger atomic sizes yield longer bonds. Additionally, the weighted second neighborhood parameter, which captures topological and electronic effects surrounding the bond, has a positive and significant contribution (, ).

The regression intercept was estimated at 2.3833, and the model showed favorable information criteria (AIC = −123.9, BIC = −118.7). These results demonstrate that the selected descriptors not only have strong statistical support but also convey meaningful physical interpretations, making the model robust and interpretable for predicting bond lengths in molecular systems.

To assess the generalization of the fitted OLS model, 5-fold cross-validation was performed on the selected feature set. In each fold, the data were randomly partitioned (shuffle seed = 42) into training and testing, and the mean squared error (MSE) and coefficient of determination were recorded.

Across the five folds, the MSE ranged from

to

(mean =

,

) and

ranged from

to

(mean =

,

). These narrow intervals indicate that the model’s predictive performance is both strong and stable across different data splits. The consistency of the

value also suggests that multicollinearity and over-fitting are unlikely to bias the estimates. A full breakdown of fold-level metrics is given in

Table 4.

After fitting and validating the final regression model, we proceed to verify that the classical assumptions underlying linear regression are satisfied. In particular, we assess the following:

Potential outliers are identified and evaluated for exclusion. There are different ways of checking whether these assumptions are met; in this study, we primarily employ diagnostic plots (e.g., residual vs. fitted, Q–Q plots) to visually confirm that these assumptions hold.

Figure 5 shows the residuals plotted against the fitted values.

Figure 6 displays a Q–Q plot comparing the sample quintiles of the observed variable with the corresponding theoretical quintiles.

The points in the Q–Q plot lie closely along the 45 degree reference line, indicating that the residuals are strongly correlated with the expected values.

Lastly, a histogram of residuals is plotted to check the distribution of the residuals, as shown in

Figure 7.

The residuals exhibit the characteristic bell-shaped curve of a normal distribution, thereby confirming that the model’s assumption of normally distributed errors holds.

3.2.2. Model 2

We examine luteolin by dividing its molecular graph into two main components:

ring edges and

terminal edges. Ring bonds form closed loops within the molecule and share electrons across the ring, which makes their bond lengths more uniform. In contrast, terminal bonds are found at the ends of the molecule, where the bonding is more localized and mainly depends on the types of atoms involved. In flavonoids like luteolin, rings show strong electron sharing, while terminal parts have more isolated bonds, such as the carbon–oxygen double bond on ring C, which behaves more like an end group than part of the ring system. As illustrated in

Figure 2, luteolin consists of two benzene rings (labeled

A and

B) and an oxygen-containing heterocyclic ring (labeled

C) with a carbon–oxygen double bond and two hydroxyl substituents on each benzene ring. Accordingly, we define:

- 1.

Ring edges: All bonds forming the rings A, B, and C.

- 2.

Terminal edges: The carbon–oxygen single bonds external to the C ring, the oxygen–hydrogen bonds, the carbon–hydrogen bonds, and the carbon–oxygen double bond located on the C ring.

Each component is analyzed separately under the hypothesis that the graph parameters defined above govern bond lengths. Accordingly, we introduce two multiple-regression models with interaction terms, one for each component, to quantify the influence of these parameters. The constants in our models were estimated using the dataset of Zheng [

17]. For the ring edges, we propose a multiple linear regression model that includes a three-way interaction term, allowing each parameter’s effect to depend simultaneously on the other two. The model for the ring edges is specified as follows:

where

denotes the valency-based parameter,

represents the product of the weighted eccentricities of the atoms forming the bond, and

corresponds to the weighted second neighborhood of the respective bond edges, calculated with respect to the electronegativities of the atoms involved. The terms

, for

, are model constants.

Fitting the model to the data by Cox [

14], we obtain the values of the constants as follows:

For the terminal edges, we propose a multiple linear regression model that incorporates a two-way interaction term, allowing the effect of one descriptor to depend on the other. The model is expressed as follows:

where

represents the sum of the radii of the atoms forming the bond, and

corresponds to the weighted second neighborhood of the respective bond edges, calculated with respect to the electronegativities of the atoms involved. The terms

, for

, are model constants.

Fitting the model to the data by Cox [

14], we obtain the values of the constants as follows:

Combining the two models (

6) and (

7) accurately predicts the bond length of all the edges in the compound luteolin, with

, adjusted

, and root mean square

.

The plots of the fit using the least square fitting method and the residuals are given in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9.

The model fitting plot shows a strong linear relationship between predicted and experimental bond lengths, with an value of , indicating that over of the variability in the experimental bond lengths is explained by the model. The points closely follow the identity line, confirming high predictive accuracy.

The residual plot, which displays residuals versus predicted values, helps assess model assumptions. Ideally, residuals should be randomly scattered around zero without any clear pattern. In this case, most residuals are tightly clustered around zero, and no clear pattern is observed.

4. Model Testing and Performance

The predictive performance of the proposed models (Model 1 and Model 2) was benchmarked against the established method of Schomaker and Stevenson [

8] and quantum-chemical calculations performed at the Parametric Method 6 (PM6) level using MOPAC. This evaluation was conducted on a hold-out set of six bonds, specifically

–

,

–

,

–

,

–

,

–

, and

–

, which were systematically omitted from the training datasets to provide an independent test of predictive performance. The comparative results are summarized in

Table 5.

With only a negligible difference between the two models’

values, we evaluated their predictive performance on the six testing edges relative to Schomaker’s model and the parametric method 6 (PM6) using adjusted

, the root mean square error (RMSE), and the mean absolute error (MAE).

Table 6 presents the adjusted

, RMSE, and MAE for all four models. Models 1 and 2 demonstrate competitive predictive accuracy compared to the parametric method 6 and slightly superior to Schomaker’s model, with Model 1 yielding the lowest root mean square error and mean absolute error, indicating that it provides the best overall performance.

This comparison demostrates that Models 1 and 2 represent improved formulations over both the Schomaker–Stevenson model [

8] and the PM6 computational method. Their superior performance suggests that the models may have captured additional interatomic interactions within the compound that were not accounted for in the earlier approaches.

Model Validation and Benchmarking

Experimental bond-length data obtained from crystallographic studies of three flavonoids were used to provide an informative validation of the proposed models. Accordingly, three comparative tables were developed to evaluate the bond lengths predicted by Model 1, Model 2, the semi-empirical PM6 method, and the Schomaker–Stevenson model against the corresponding experimental measurements. Statistical performance indicators, including the coefficient of determination (), root mean square error (RMSE), and mean absolute error (MAE), were employed to assess predictive accuracy quantitatively.

Table 7,

Table 8 and

Table 9 provides a comparative evaluation of the predictive performance of Model 1, Model 2, the Schomaker–Stevenson model, and the Parametric Method 6 (PM6) based on bond-length data for quercetin, kaempferol and -(-)epicatechin reported in [

9,

18,

19], respectively. The comparison underscores the relative accuracy and internal consistency of the proposed graph-theoretical models when compared to semi-empirical computational approaches. Notably, Models 1 and 2 exhibit predictive accuracies closely aligned with experimental measurements, demonstrating their robustness and suggesting their potential applicability to other flavonoid compounds with comparable structural complexity.

The results indicate that both proposed models reproduce the experimental geometries with accuracy comparable to, and in some instances exceeding, that of the PM6 method. This suggests that the underlying graph-theoretical framework effectively captures essential structural features of flavonoid systems. However, the current validation is limited by the small number of experimentally characterized compounds. A more statistically robust evaluation would require expanding the dataset to include a broader range of flavonoid structures.

The predictive performance of the models was evaluated based on the adjusted

, the root mean square error, and the mean absolute error, as summarized in

Table 10. The comparative evaluation of the four predictive approaches across three flavonoid compounds demonstrates that both graph-theoretical models, particularly Model 2, exhibit strong predictive accuracy and consistency relative to semi-empirical methods. On average, Model 2 achieved the highest adjusted

values and the lowest RMSE and MAE across all datasets, indicating superior alignment with experimental bond lengths. Model 1 also performed competitively, often surpassing the PM6 semi-empirical method in both error metrics. In contrast, the Schomaker–Stevenson model consistently displayed the weakest predictive performance. Overall, the findings suggest that the proposed graph-theoretical framework offers a reliable and broadly applicable method for representing and predicting the structural characteristics of flavonoid compounds exhibiting comparable molecular architectures.

Given the limited availability of experimental bond-length data for the compounds under study, the semi-empirical parametric method 6 (PM6) was adopted as a computational benchmark for model validation. The performance of the proposed models was evaluated by comparing the predicted bond lengths against PM6 reference values using standard statistical measures, including the coefficient of determination (

), and the root mean square error (RMSE). Consistently high correlations demonstrate that the graph-theoretical descriptors effectively reproduce PM6-level geometric trends. Nevertheless, further validation against experimental measurements, once such data become available, remains necessary to establish the absolute predictive accuracy of the models. The predictive capability of the proposed models was further evaluated using an independent validation dataset comprising four flavonoid compounds, apigenin, genistein, hesperetin, and catechin. For each compound, the bond lengths predicted by Model 1 and Model 2 were compared against PM6-optimized geometries to assess the models’ generalization performance across structurally related flavonoids. Since the numerical trends can be clearly intepreted from the tabulated results, graphical figures were deemed unnecessary. The complete results are presented in

Table 11,

Table 12,

Table 13,

Table 14 and

Table 15.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

This study presents a graph-theoretical framework for estimating bond lengths in molecular systems, demonstrated using flavonoid compounds as a case study. The results highlight the capability of mathematical models to predict key structural parameters with high accuracy, offering a computationally efficient alternative to traditional experimental and quantum-chemical methods. While experimental determination of bond lengths remains resource-intensive, the proposed models provide a reliable means of approximation based on topological and atomic descriptors.

The correlation analysis indicated that the sum of covalent radii, , was the most significant predictor of bond length, exhibiting a correlation coefficient of , consistent with established physical principles. The weighted second-neighborhood parameter, which quantifies the electronegativity-weighted atomic environment around a bond, also contributed meaningfully by capturing local electronic delocalization effects. Together with bond order, these descriptors formed the basis of Model 1, which achieved a high predictive accuracy (). Model 2, incorporating weighted eccentricity and neighborhood-based parameters, likewise demonstrated strong performance. These results suggest that combining atomic-scale geometric and electronic descriptors within a graph-theoretical framework can yield quantitatively accurate bond-length predictions.

In comparing predictive performance, both models achieved results comparable to the Parametric Method 6 (PM6) and superior to the classical Schomaker–Stevenson formulation. This indicates that graph-theoretic descriptors can effectively approximate quantum-derived bond-length data while offering major advantages in computational simplicity and interpretability. However, these findings are presently limited to the flavonoid compounds examined and should not be generalized beyond molecules with similar structural and electronic characteristics without further validation.

Luteolin was selected as a representative case within the subclass of polyphenolic flavonoids due to its well-characterized structure and availability of experimental bond-length data. Nonetheless, the flavonoid family is structurally diverse, encompassing numerous subclasses with varying degrees of conjugation, hydroxylation, and substitution patterns. Thus, luteolin cannot be considered representative of all flavonoids, but rather of compounds sharing analogous molecular topologies. Future work should systematically evaluate the applicability of the proposed model across broader flavonoid subclasses and other organic compound families.

While the present models demonstrate strong internal consistency and agreement with experimental data, their predictive generality remains to be established. The current dataset is limited in chemical scope, and further testing on larger, structurally diverse molecular datasets will be necessary to assess the robustness of the approach. Consequently, the proposed framework should be viewed as an initial step toward a generalizable model, pending validation across multiple compound classes.

Several refinements could enhance the current formulation. Incorporating geometric parameters such as bond angles and torsional strain, as well as energetic descriptors like bond dissociation energy, would likely improve predictive accuracy. Moreover, extending the molecular graph representation to three dimensions could capture spatial effects and conformational flexibility not accounted for in planar models. Future developments may also leverage nonlinear regression and graph-based machine learning algorithms, such as graph neural networks, to model complex, higher-order dependencies among descriptors.

Beyond bond-length prediction, the proposed framework provides a foundation for broader applications in computational chemistry and cheminformatics. The identified descriptors, sum of covalent radii, weighted neighborhood indices, bond order, and weighted eccentricity can serve as key features for quantitative structure–property or structure–activity models. These descriptors could aid in predicting molecular stability, reactivity, or biological activity when combined with experimental or simulated datasets.

In summary, this work introduces a mathematically rigorous and computationally efficient approach to molecular geometry prediction using graph-theoretical methods. The results demonstrate that topological and atomic descriptors can provide physically meaningful estimates of bond lengths for selected flavonoid compounds. Although the general applicability of the model requires further validation across diverse molecular families, the findings establish a strong conceptual and methodological basis for future exploration of graph-theoretic models in chemical structure prediction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S.A.A., E.J., R.J.M., E.M.-B., M.Z., S.M. and F.N.; methodology, S.M., F.N., M.Z. and A.S.A.A.; software, S.M., F.N., M.Z. and A.S.A.A.; formal analysis, S.M., F.N. and M.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, M.Z. and A.S.A.A.; writing—review and editing, S.M., F.N., M.Z. and A.S.A.A.; supervision, E.J., R.J.M., E.M.-B., S.M. and F.N.; project administration, S.M. and F.N.; funding acquisition, S.M. and F.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the DSI-NRF Centre of Excellence in Mathematical and Statistical Sciences (CoE-MaSS), South Africa, and the IMU-CDC project grant.

Data Availability Statement

All crystallographic data used in this study are publicly available from the references cited in the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Harsányi, L.; Császár, A.; Császár, P. Equilibrium geometries of uracil and its C- and N-methylated derivatives. J. Mol. Struct. Theochem 1986, 137, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, F.; Kennard, O.; Watson, D.; Brammer, L.; Orpen, A.; Taylor, R. Tables of bond lengths determined by X-ray and neutron diffraction. Part 1. Bond lengths in organic compounds. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1987, 2, S1–S19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalaji, A.; Mighani, H.; Kazemnejadi, M.; Gotoh, K.; Ishida, H.; Fejfarova, K.; Dusek, M. Synthesis, characterization, crystal structure and theoretical studies on 4-bromo-2-[(E)-6- methyl-2-pyridyliminomethyl] phenol. Arabian J. Chem 2017, 10, S1808–S1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, J.C. Atomic Radii in Crystals. J. Chem. Phys. 1964, 41, 31–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauling, L. Bond numbers and bond lengths in tetrabenzo[de,no,st,c1,d1] heptacene and other condensed aromatic hydrocarbons: A valence bond treatment. Struct. Sci. 1980, 36, 1898–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauling, L.; Brockway, L.O.; Beach, J.Y. The dependence of inter atomic distance on single bond-double bond resonance. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1935, 57, 2705–2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulson, C.A. The electronic structure of some polyenes and aromatic molecules. VII. Bonds of fractional orders by the molecular orbital method. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 1939, 169, 413–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schomaker, V.; Stevenson, D.P. Some Revisions of the Covalent Radii and the Additivity Rule for the Lengths of Partially Ionic Single Covalent Bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1941, 63, 37–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, M.; Rickles, L.F.; Halpin, W.A. The crystal and molecular structure of quercetin: A biologically active and naturally occurring flavonoid. Bioorg. Chem 1986, 14, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzah, M.O. A Comparative Study of Bond Order and Bond Length Calculations of Some Conjugated Hydrocarbons using Two Different Methods. Adv. Res. Chem. Sci. 2017, 24, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, P.F.; Smith, B. Single Bond Lengths of Organic Molecules in the Solid State. Glob. J. Sci. Front. Res. 2015, 16, 55–60. [Google Scholar]

- Gutman, I.; Polansky, O.E. Chemical Graphs. In Mathematical Concepts in Organic Chemistry; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cayley, F.R.S. On the mathematical theory of isomers. Lond. Edinb. Dublin Philos. Mag. J. Sci. 1874, 47, 444–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, P.; Kumarasamy, Y.; Nahar, L.; Sarker, S.; Shoeb, M. Luteolin. Acta Cryst. 2003, 59, o975–o977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, M. WebElements: The Periodic Table on the Web; Copyright Mark Winter, University of Sheffield: Sheffield, UK. Available online: https://www.webelements.com/ (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. Electronegativity in the Periodic Table of Elements. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/periodic-table/electronegativity (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Zheng, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Liang, Q.; Chen, D.; Guo, R. Theoretical studies on the hydrogen-bonding interactions between luteolin and water: A DFT approach. J. Mol. Model. 2016, 22, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milenković, D.; Marković, J.M.D.; Dimić, D.; Jeremić, S.; Amić, D.; Pirković, M.S.; Marković, Z.S. Structural characterization of kaempferol: A spectroscopic and computational study. Maced. J. Chem. Chem. Eng. 2019, 38, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fronczek, F.R.; Gannuch, G.; Mattice, W.L.; Tobiason, F.L.; Broeker, J.L.; Hemingway, R.W. Dipole moment, solution, and solid state structure of (–)-epicatechin, a monomer unit of procyanidin polymers. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1984, 2, 1611–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |