Clinical Prediction and Spatial Statistical Analysis of Ascending Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm Structure

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Clinical Variables

2.2. Aortic Data

2.3. Empirical Variogram and Model Fitting

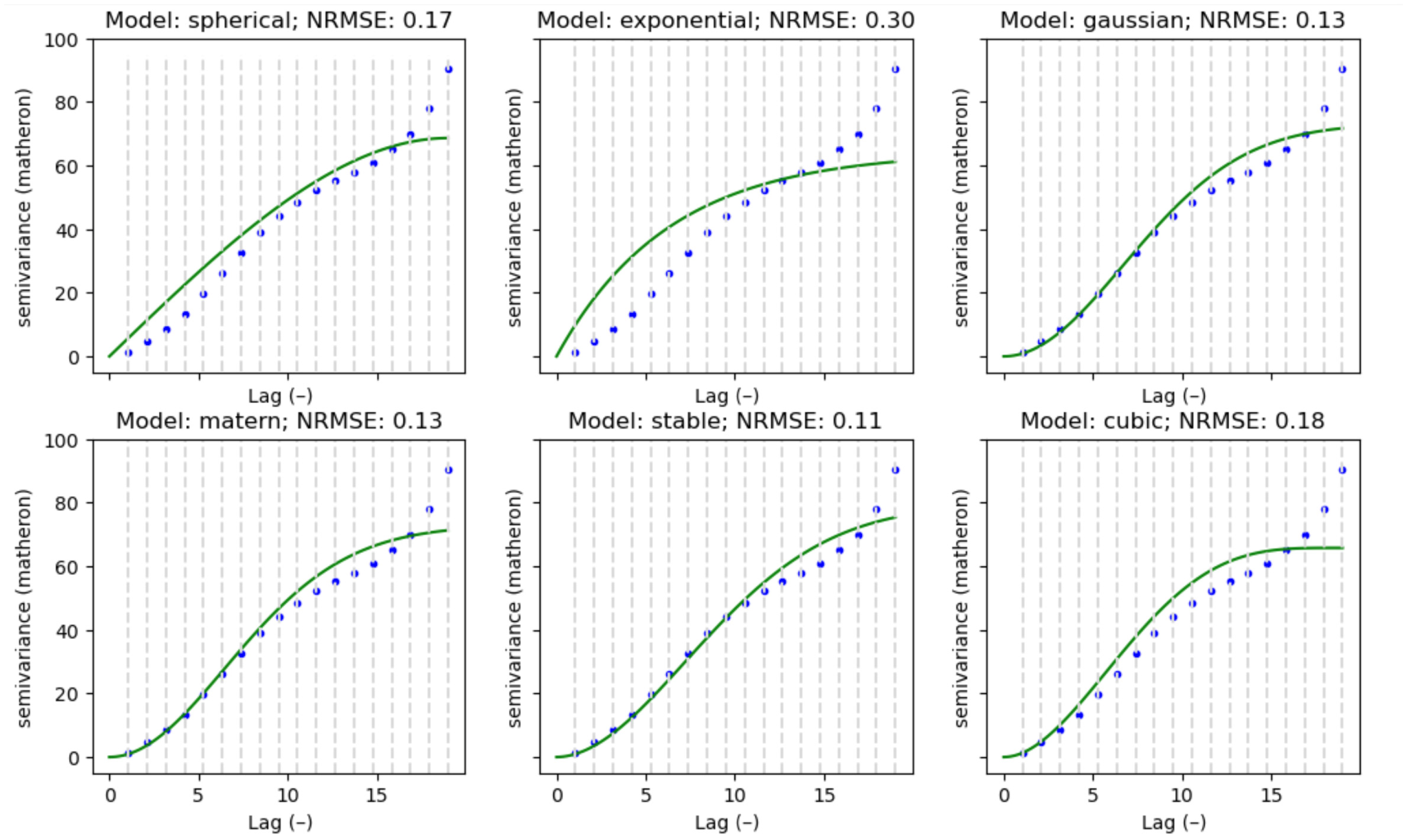

- Spherical: This model describes a gradual increase in variability with distance, until it stabilizes at a maximum range.

- Exponential: The exponential model describes variability that increases continuously and more rapidly with distance.

- Gaussian: Similarly to the exponential model, but with a smoother decrease.

- Matern: This model is a generalization of the earlier ones and includes an additional parameter that controls the smoothness of the function.

- Stable: The stable model is used for phenomena that show irregular variability, even at large distances.

- Cubic: Variability increases or decreases cubically with distance.

2.4. Aortic Data Processing

- Data collection: For each patient, the data was read from their corresponding file. Each dataset contained a series of observations taken over time, which included various spatial measurements of the region of interest. These data points served as the foundation for the subsequent analysis.

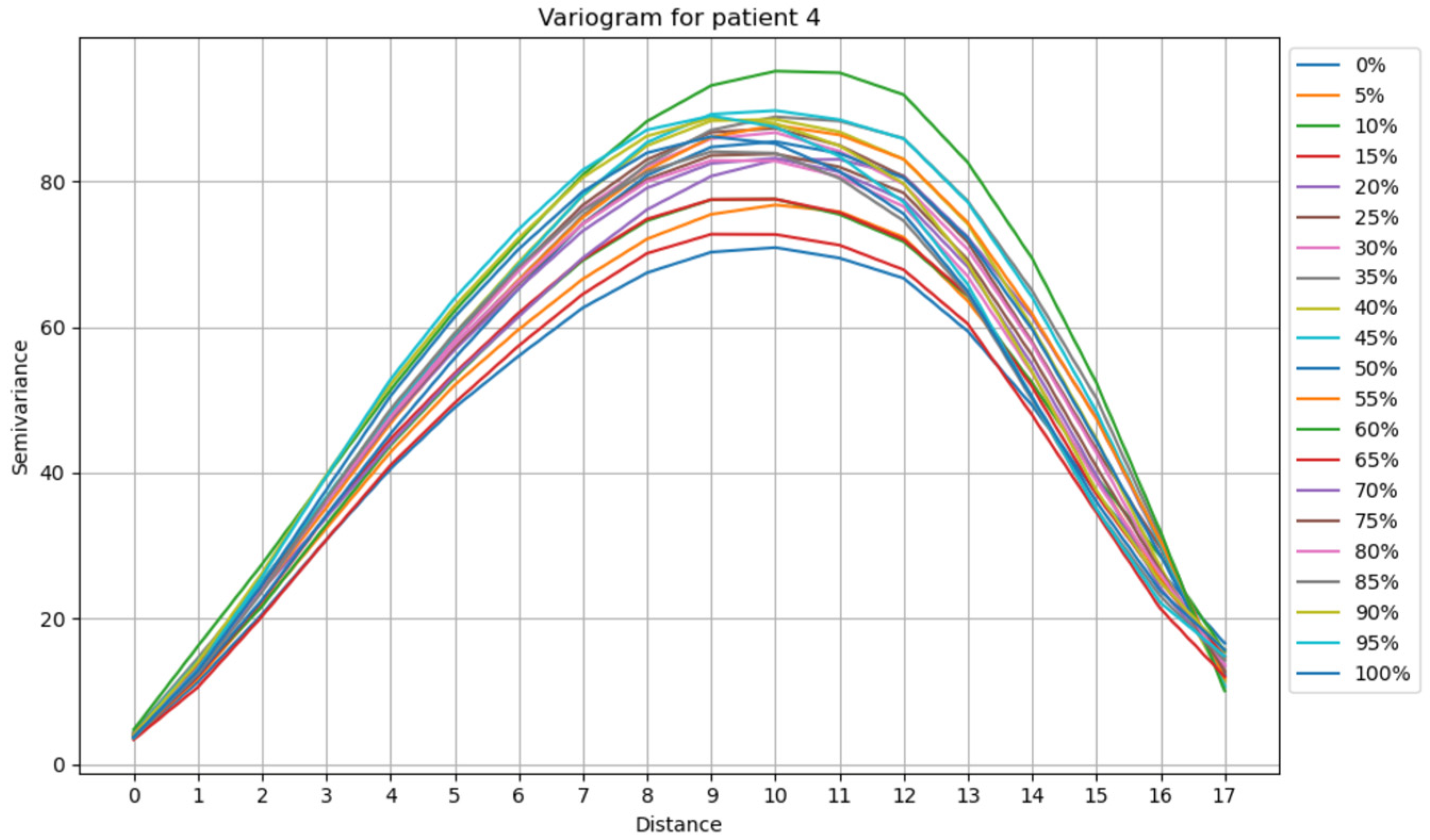

- Distance setup: A predefined set of distances, ranging from 0 to 19 units, was selected to characterize the spatial relationship between the measurement points. These distances represent the intervals over which the differences in the data points were calculated and compared.

- Variogram calculation: For each observation, the experimental variogram was computed using the selected distances. The variogram quantifies the spatial correlation between the measurements at different distances by calculating the squared differences between the values and their spatial lag. The variogram also provides insights into the spatial structure and dependencies of the data.

- Parameter estimation: In addition to calculating the experimental variogram, key parameters of the variogram model were estimated. Twenty experimental variograms were calculated (one for each time point: 0%, 5%,10%, etc.) for each patient. Then, the models mentioned in the previous subsection were used to construct 21 theoretical variograms for each patient with each model. The goal was to determine which model best fits the experimental variograms for each patient (Figure 3). To achieve this, the Normalized Root Mean Squared Error (NRMSE) was calculated for each patient and each model. NRMSE is a metric used to assess the accuracy of a model’s predictions while accounting for the scale of the data. It is a variation in the Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) but normalized to make it more interpretable across different datasets [20].

- Nugget: This parameter represents the small-scale variation or noise in the data, typically reflecting measurement error or fine-scale variability. It corresponds to the value of the variogram at distance zero.

- Sill: The sill represents the plateau level of the variogram, indicating the point at which the spatial correlation between measurements becomes negligible, and further increases in distance no longer influence the variance.

- Range: The range is the distance at which the variogram reaches the sill, indicating the effective spatial distance over which measurements are correlated.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Description of Clinical Data

3.2. Analysis of the Empirical Variogram

Analysis of the Variograms Parameters

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vasan, R.S.; Pan, S.; Xanthakis, V.; Beiser, A.; Larson, M.G.; Seshadri, S.; Mitchell, G.F. Arterial stiffness and long-term risk of health outcomes: The Framingham Heart Study. Hypertension 2022, 79, 1045–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dieter, R.; Dieter, R.; Dieter, R., III. Diseases of the Aorta; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pasta, S.; Rinaudo, A.; Luca, A.; Pilato, M.; Scardulla, C.; Gleason, T.G.; Vorp, D.A. Difference in hemodynamic and wall stress ofascending thoracic aortic aneurysms with bicuspid and tricuspid aortic valve. J. Biomech. 2013, 46, 1729–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pham, T.D.; Golledge, J. Pattern analysis of imaging markers in abdominal aortic aneurysms. In Proceedings of the 2013 6th International Conference on Biomedical Engineering and Informatics, Hangzhou, China, 16–18 December 2013; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, M.H.; Appoo, J.J.; Saczkowski, R.; Smith, H.N.; Ouzounian, M.; Gregory, A.J.; Herget, E.J.; Boodhwani, M. Association of mortality and acute aortic events with ascending aortic aneurysm: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2018, 1, e181281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erbel, R.; Aboyans, V.; Boileau, C.; Bossone, E.; Bartolomeo, R.D.; Eggebrecht, H.; Evangelista, A.; Falk, V.; Frank, H.; Gaemperli, O.; et al. 2014 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of aortic diseases. Eur. Heart J. 2014, 35, 2873–2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czerny, M.; Grabenwöger, M.; Berger, T.; Aboyans, V.; Della Corte, A.; Chen, E.P.; Desai, N.D.; Dumfarth, J.; Elefteriades, J.A.; Etz, C.D.; et al. EACTS/STS Guidelines for diagnosing and treating acute and chronic syndromes of the aortic organ. Eur. J. Cardio-Thorac. Surg. 2024, 65, ezad426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maiti, S.; Thunes, J.R.; Fortunato, R.N.; Gleason, T.G.; Vorp, D.A. Computational modeling of the strength of the ascendingthoracic aortic media tissue under physiologic biaxial loading conditions. J. Biomech. 2020, 108, 109884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farzaneh, S.; Trabelsi, O.; Avril, S. Inverse identification of local stiffness across ascending thoracic aortic aneurysms. Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol. 2019, 18, 137–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansour, A.M.; Peterss, S.; Zafar, M.A.; Rizzo, J.A.; Fang, H.; Charilaou, P.; Ziganshin, B.A.; Darr, U.M.; Elefteriades, J.A. Prevention of aortic dissection suggests a diameter shift to a lower aortic size threshold for intervention. Cardiology 2018, 139, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tjahjadi, N.S.; Kim, T.; Marway, P.S.; Jorge, C.A.C.; Baker, T.J.; Hazenberg, C.; van Herwaarden, J.A.; Patel, H.J.; Figueroa, C.A.; Burris, N.S. Three-dimensional assessment of ascending aortic stiffness, motion, and growth in ascending thoracic aortic aneurysm. Eur. Heart J.-Imaging Methods Pract. 2025, 3, qyae133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.; Morgant, M.C.; Marín-Castrillón, D.M.; Walker, P.M.; Glélé, L.S.A.; Boucher, A.; Presles, B.; Bouchot, O.; Lalande, A. Aortic local biomechanical properties in ascending aortic aneurysms. Acta Biomater. 2022, 149, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valente, R.; Mourato, A.; Carvalho, A.; Xavier, J.; Brito, M.; Avril, S.; Tomás, A.; Fragata, J. Patient-Specific In-vivo Dynamic Motion of Ascending Thoracic Aortic Aneurysms from Cine CTA. 2025; submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, K.P. Machine Learning: A Probabilistic Perspective; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mai, C.K.; Reddy, A.B.; Raju, K.S. Machine Learning Technologies and Applications; Springer: Singapore, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, A.C.; Guido, S. Introduction to Machine Learning with Python: A Guide for Data Scientists; O’Reilly Media, Inc.: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Webster, R.; Oliver, M. Geostatistics for Environmental Scientists; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Moraga, P. Spatial Statistics for Data Science: Theory and Practice with R; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Mahdi, E.; Abuzaid, A.H.; Atta, A.M.A. Empirical variogram for achieving the best valid variogram. Commun. Stat. Appl. Methods 2020, 27, 547–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyndman, R.J.; Koehler, A.B. Another look at measures of forecast accuracy. Int. J. Forecast. 2006, 22, 679–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redheuil, A.; Yu, W.-C.; Wu, C.O.; Mousseaux, E.; de Cesare, A.; Yan, R.; Kachenoura, N.; Bluemke, D.; Lima, J.A.C. Reduced ascending aortic strain and distensibility: Earliest manifestations of vascular aging in humans. Hypertension 2010, 55, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Oviedo Rodríguez, K.; Carvalho, A.; Valente, R.; Xavier, J.; Tomás, A.C. Clinical Prediction and Spatial Statistical Analysis of Ascending Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm Structure. Math. Comput. Appl. 2026, 31, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/mca31010010

Oviedo Rodríguez K, Carvalho A, Valente R, Xavier J, Tomás AC. Clinical Prediction and Spatial Statistical Analysis of Ascending Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm Structure. Mathematical and Computational Applications. 2026; 31(1):10. https://doi.org/10.3390/mca31010010

Chicago/Turabian StyleOviedo Rodríguez, Katalina, Alda Carvalho, Rodrigo Valente, José Xavier, and António Cruz Tomás. 2026. "Clinical Prediction and Spatial Statistical Analysis of Ascending Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm Structure" Mathematical and Computational Applications 31, no. 1: 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/mca31010010

APA StyleOviedo Rodríguez, K., Carvalho, A., Valente, R., Xavier, J., & Tomás, A. C. (2026). Clinical Prediction and Spatial Statistical Analysis of Ascending Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm Structure. Mathematical and Computational Applications, 31(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/mca31010010