Comparative Performance Analysis of Machine Learning Models for Compressive Strength Prediction in Concrete Mix Design

Abstract

1. Introduction

Research Significance

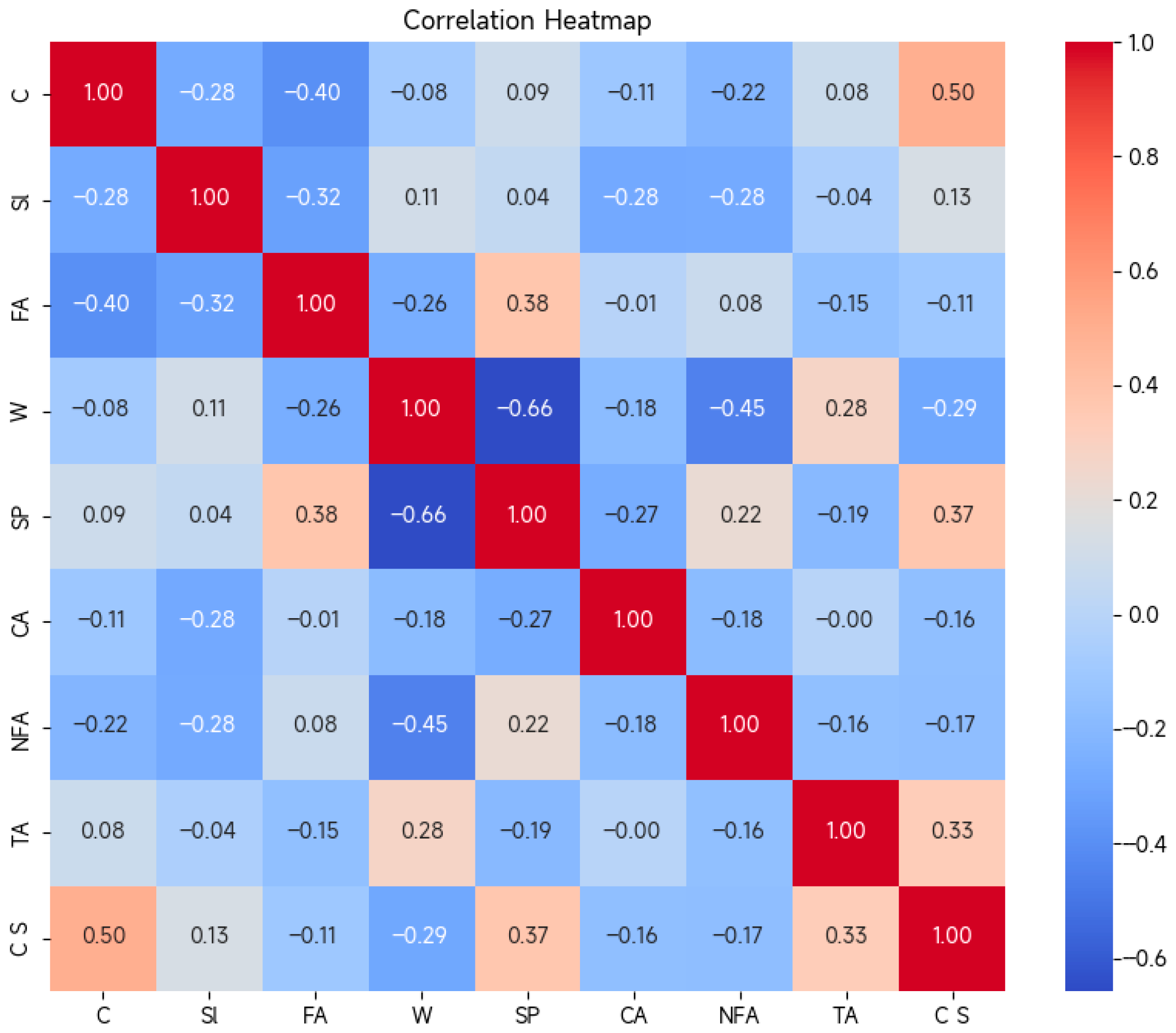

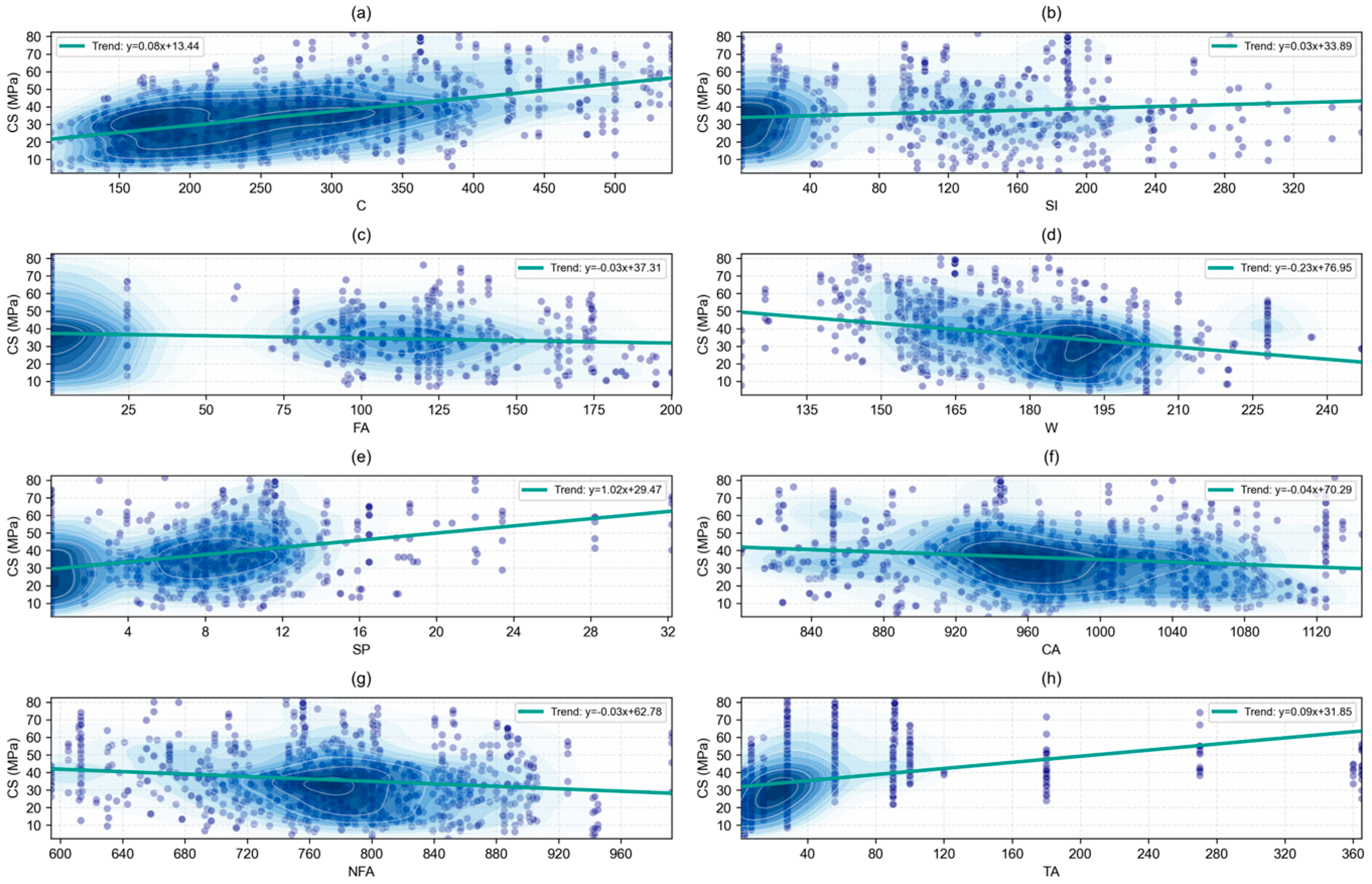

2. Data Preparation

3. Methodology

3.1. Elastic Net Regression

3.2. KNN

3.3. ANN

3.4. SVR

3.5. Random Forest

3.6. XGBoost

3.7. Category Boosting (CatBoost)

3.8. Symbolic Regression

3.9. Statistical Metrics for Model Assessment

3.10. Stacking Technique

3.11. SHAP Analysis

3.12. Model Generalization

4. Model Results

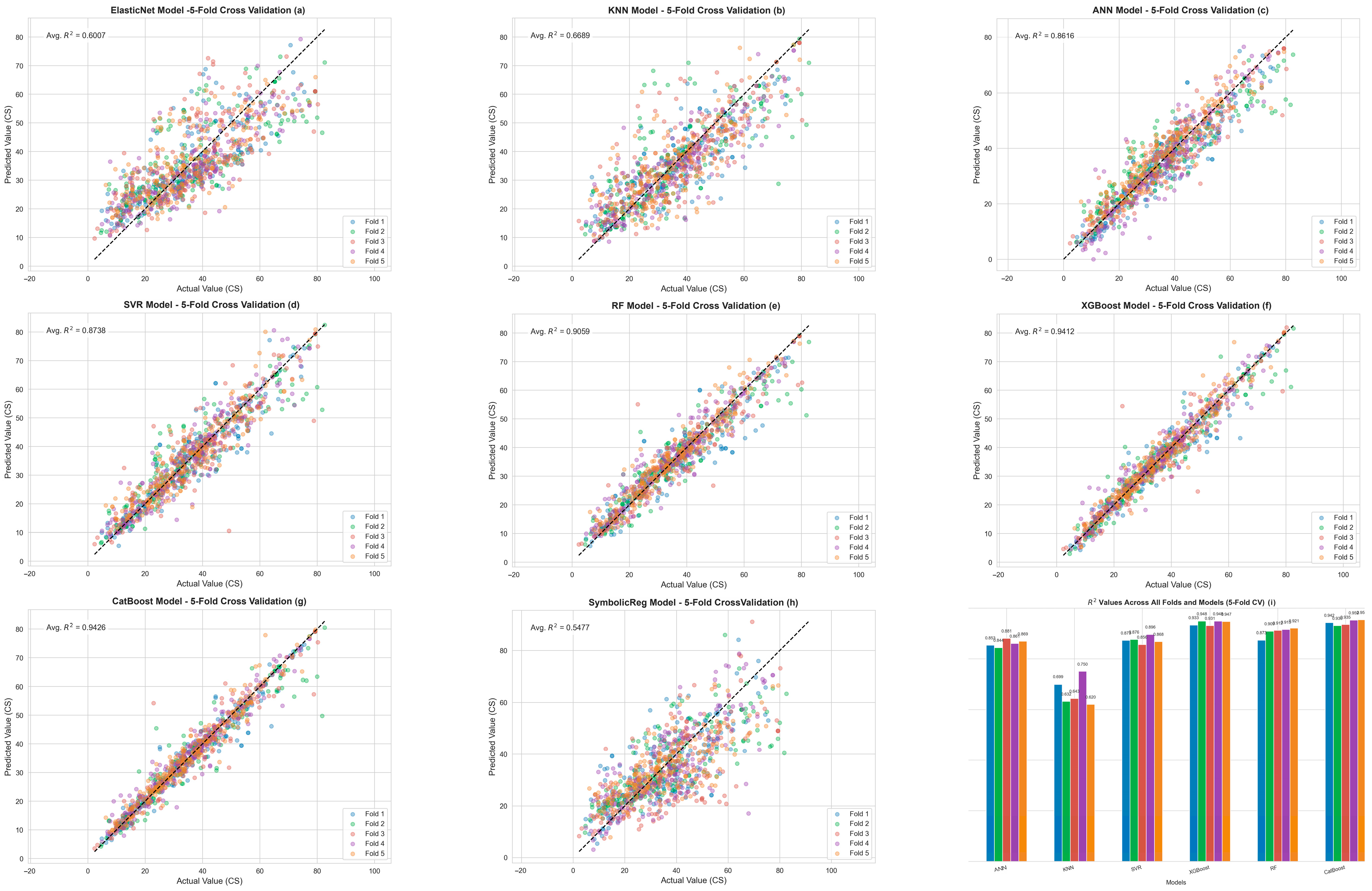

4.1. K-Fold Cross-Validation

4.2. ML with Elastic Net Regression Model Outcomes

4.3. ML with KNN Model Outcomes

4.4. ML with ANN Model Outcomes

4.5. ML with SVR Model Outcomes

4.6. ML with RF Model Outcomes

4.7. ML with XGBoost Model Outcomes

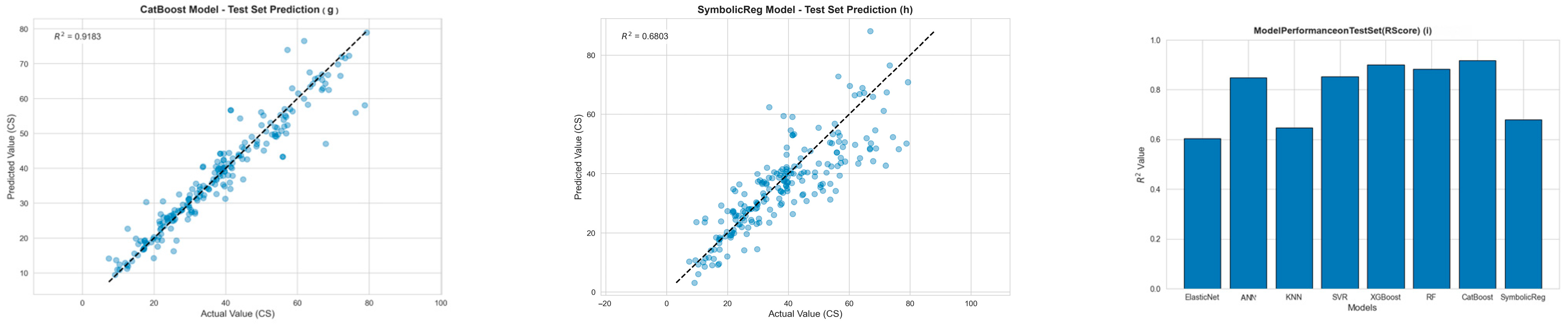

4.8. ML with CatBoost Model Outcomes

4.9. ML with Symbolic Regression Outcomes

4.10. Stacking Model Outcomes

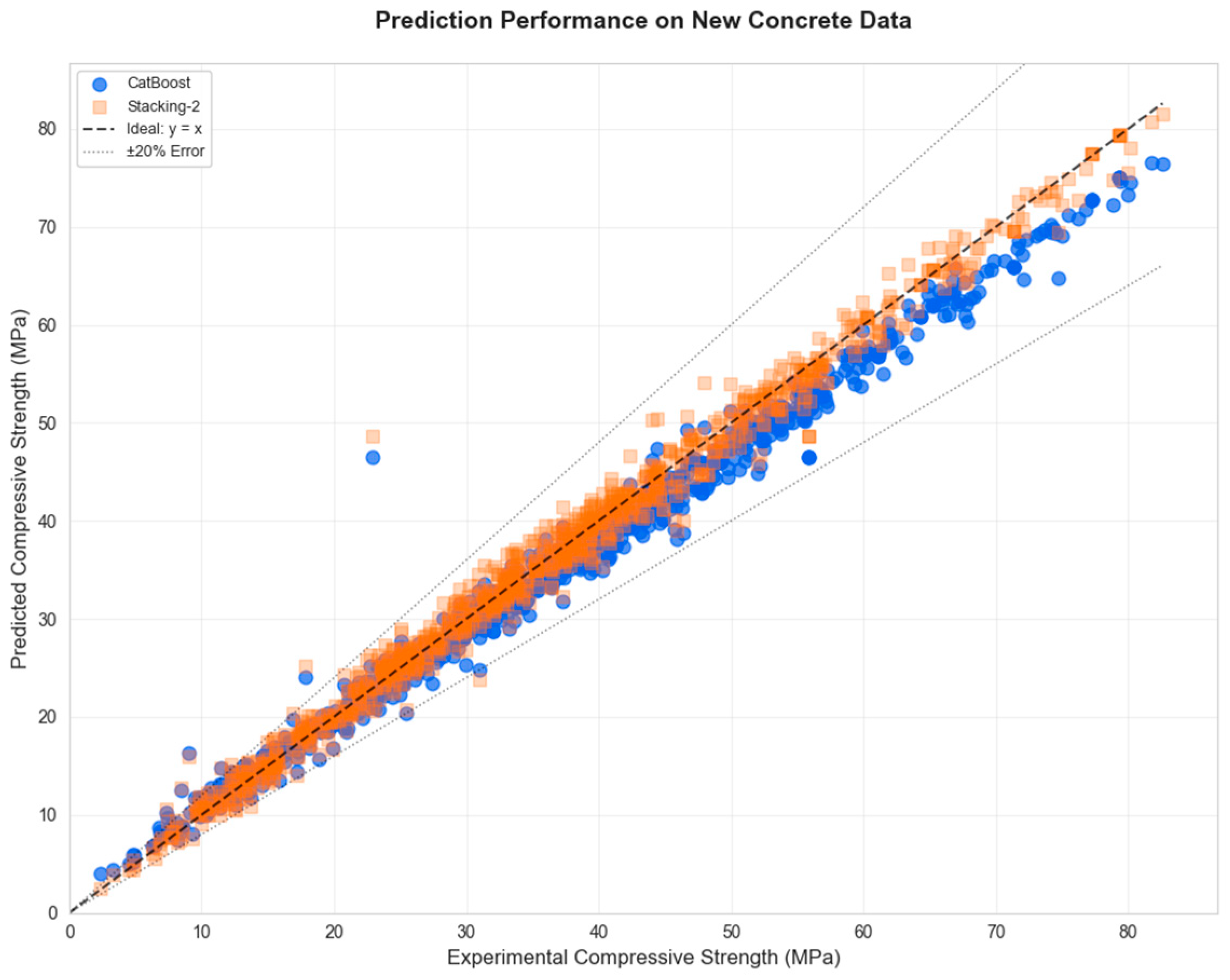

4.11. External Validation Outcomes

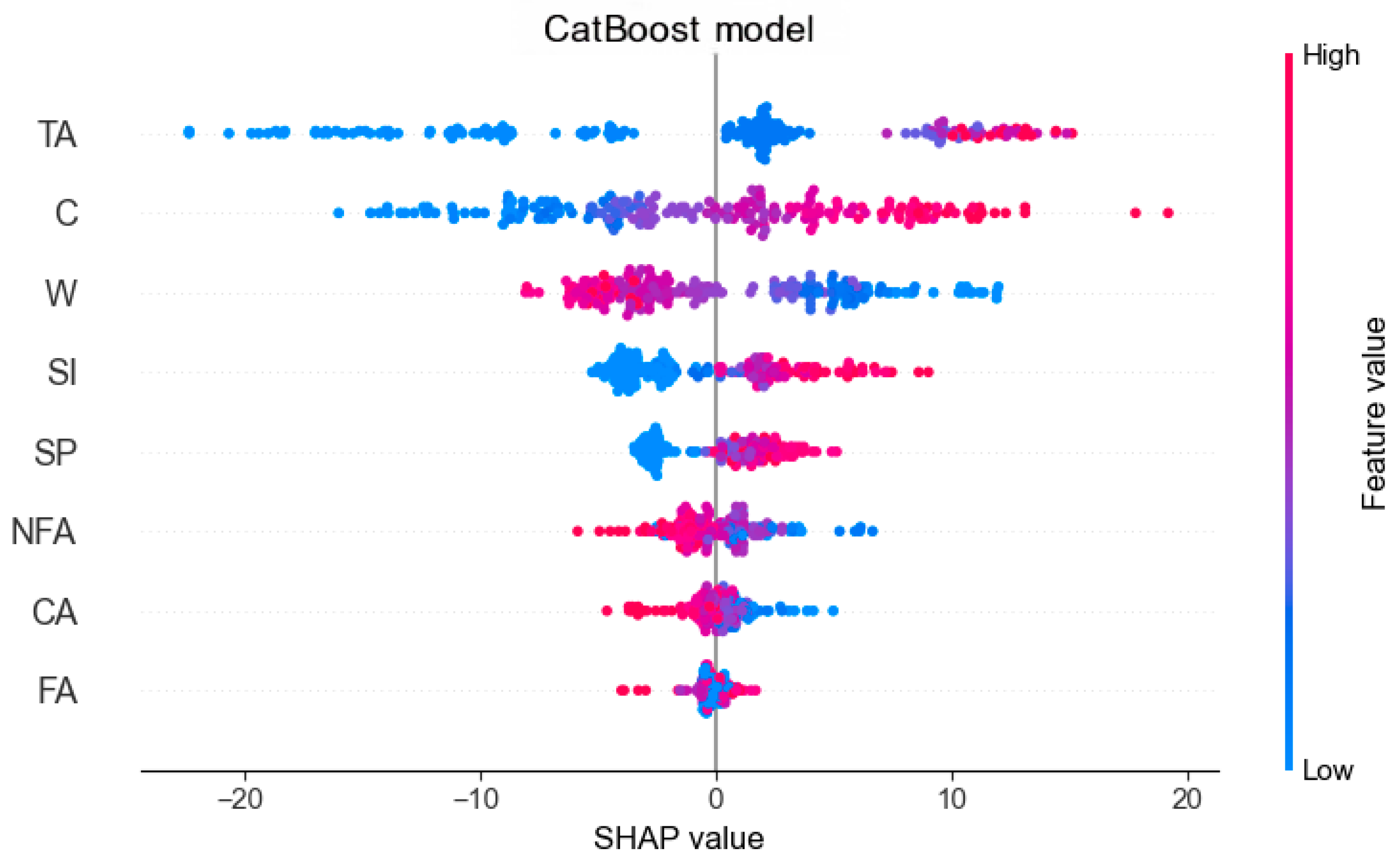

4.12. Sensitivity Analysis Outcomes

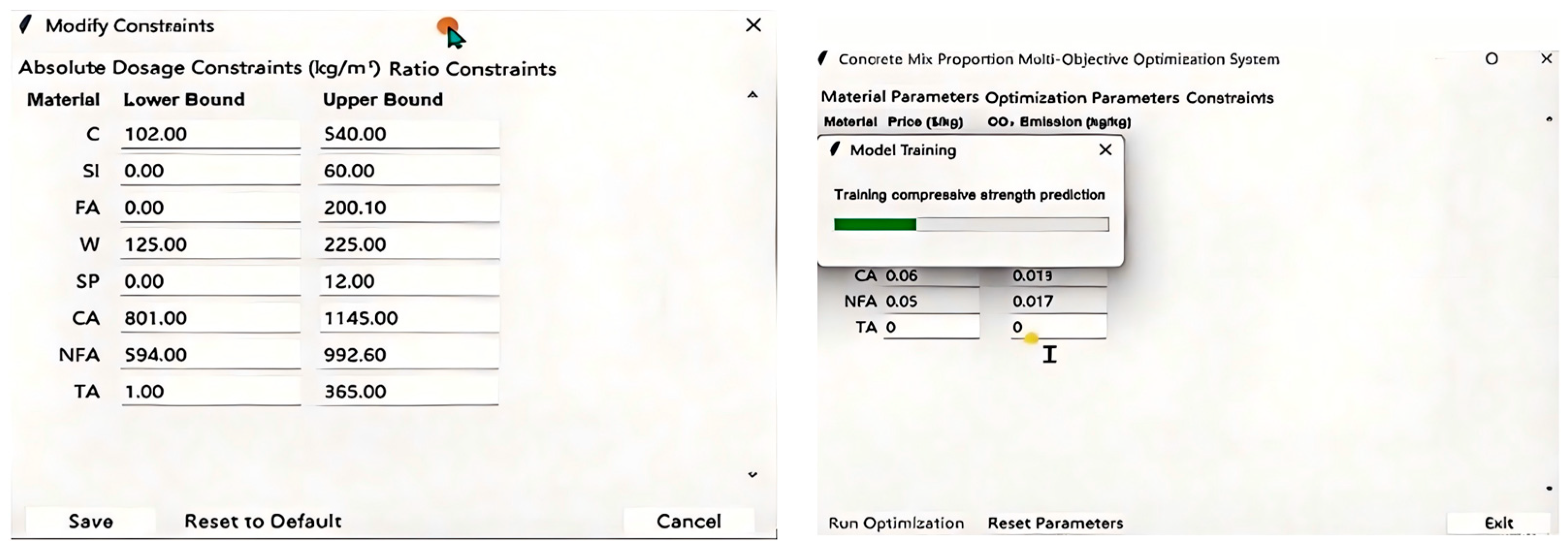

4.13. Development of Graphical User Interface

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- Key outcomes: This study developed and validated a machine learning framework for concrete compressive strength prediction using 1030 UCI dataset samples with eight input parameters (cement, slag, fly ash, water, coarse aggregate, natural fine aggregate, superplasticizer, testing age). Among elastic net, KNN, ANN, SVR, RF, XGBoost, CatBoost, stacking models, and symbolic regression, CatBoost and stacking approaches achieved superior performance via harmonized preprocessing, five-fold cross-validation, and unified SHAP interpretation. External validation with the independent literature data confirmed robust generalizability, identifying cement and testing age as the most critical predictors through sensitivity analysis. A GUI was developed. It enables engineers and researchers to access the CS rapidly, presenting an extremely user-friendly interface to facilitate the use of a machine learning model. It is adaptable to new assumptions, and various scenarios to be obtained in future analyses.

- (2)

- Practical significance: The proposed ML pipeline reduces experimental costs and time by enabling rapid, accurate CS prediction without extensive laboratory testing. Standardized evaluation metrics (R2, MAE, RMSE, MAPE, SI) and interpretable SHAP-based sensitivity analysis facilitate sustainable concrete mix optimization, supporting environmentally conscious material design in civil engineering applications.

- (3)

- Future directions: The power of ML models is their data-driven ability, instead of the explicit understanding of underlying physical mechanisms. This means constant and rigorous laboratory validation are needed. CS is determined by many other parameters, including factors like concrete composition, water–cement ratios, moisture levels, substitution rates, diverse environmental factors, etc. [104]. Moving forward, researchers could explore sophisticated data through experimental work, field tests, and other numerical analyses using various methods to better handle CS prediction. The more we understand about the concrete composition versus CS relationship, the better we can understand the nature of concrete and how to optimize the concrete mixture [105,106]. Additionally, future investigations of integrated modeling approaches combining multiple algorithms should be conducted to enhance CS predictive accuracy. Furthermore, creating comprehensive, high-quality datasets that cover not only compressive strength but also other key properties of concrete—including RAC mixtures, which are critical for sustainable construction practices—is essential for improving the accuracy and generalization of predictive tools.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmad, W.; Ahmad, A.; Ostrowski, K.A.; Aslam, F.; Joyklad, P. A scientometric review of waste material utilization in concrete for sustainable construction. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2021, 15, e00683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwankwo, C.O.; Bamigboye, G.O.; Davies, I.E.E.; Michaels, T.A. High volume Portland cement replacement: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 260, 120445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrigoni, A.; Panesar, D.K.; Duhamel, M.; Opher, T.; Saxe, S.; Posen, I.D.; MacLean, H.L. Life cycle greenhouse gas emissions of concrete containing supplementary cementitious materials: Cut-off vs. Substitution. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 263, 121465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golafshani, E.M.; Arashpour, M.; Kashani, A. Green mix design of rubbercrete using machine learning-based ensemble model and constrained multi-objective optimization. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 327, 129518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakkamalayath, J.; Joseph, A.; Baghli, H.A.; Hamadah, O.; Dashti, D.; Abdulmalek, N. Performance evaluation of self-compacting concrete containing volcanic ash and recycled coarse aggregates. Asian J. Civ. Eng. 2020, 21, 815–827. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s42107-020-00242-2 (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Huynh, A.T.; Nguyen, Q.D.; Xuan, Q.L.; Magee, B.; Chung, T.C.; Tran, K.T.; Nguyen, K.T. A machine learning-assisted numerical predictor for compressive strength of geopolymer concrete based on experimental data and sensitivity analysis. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 7726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazouki, G.; Pourghorban, A. Using a hybrid artificial intelligence method for estimating the compressive strength of recycled aggregate self-compacting concrete. Eur. J. Environ. Civ. Eng. 2022, 26, 5569–5593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, D.-K.; Nguyen, T.; Chou, J.-S.; Nguyen-Xuan, H.; Ngo, T.D. A modified firefly algorithm-artificial neural network expert system for predicting compressive and tensile strength of high-performance concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 180, 320–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chithra, S.; Kumar, S.R.R.S.; Chinnaraju, K.; Ashmita, F.A. A comparative study on the compressive strength prediction models for High Performance Concrete containing nano silica and copper slag using regression analysis and Artificial Neural Networks. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 114, 528–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahish, H.A.; Alfawzan, M.S.; Tayeh, B.A.; Abusogi, M.A.; Bakri, M. Effect of inclusion of natural pozzolan and silica fume in cement-based mortars on the compressive strength utilizing artificial neural networks and support vector machine. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 18, e02153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thisovithan, P.; Aththanayake, H.; Meddage, D.P.P.; Ekanayake, I.U.; Rathnayake, U. A novel explainable AI-based approach to estimate the natural period of vibration of masonry infill reinforced concrete frame structures using different machine learning techniques. Res. Eng. 2023, 19, 101388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeyad, A.M.; Mahmoud, A.A.; El-Sayed, A.A.; Aboraya, A.M.; Fathy, I.N.; Zygouris, N.; Asteris, P.G.; Agwa, I.S. Compressive strength of nano concrete materials under elevated temperatures using machine learning. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 24246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahmari, T.S.; Ashraf, J.; Sobuz, M.H.R.; Uddin, M.A. Predicting the compressive strength of fiber-reinforced self-consolidating concrete using a hybrid machine learning approach. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2024, 9, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorgün, E. Characterization of superalloys by artificial neural network method. New Trends Math. Sci. 2022, 1, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.M.H.; Sobuz, M.H.R.; Meraz, M.M.; Tam, V.W.Y.; Hasan, N.M.S.; Shaurdho, N.M.N. Effect of various powder content on the properties of sustainable selfcompacting concrete. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 19, e02274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, J.-S.; Pham, A.-D. Smart artificial firefly colony algorithm-based support vector regression for enhanced forecasting in civil engineering. Comput.-Aided Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 2015, 30, 715–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonebi, M.; Cevik, A.; Grünewald, S.; Walraven, J. Modelling the fresh properties of self-compacting concrete using support vector machine approach. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 106, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyirandayisabye, R.; Li, H.; Dong, Q.; Hakuzweyezu, T.; Nkinahamira, F. Automatic pavement damage predictions using various machine learning algorithms: Evaluation and comparison. Res. Eng. 2022, 16, 100657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.-Y.; Firdausi, P.M.; Prayogo, D. High-performance concrete compressive strength prediction using Genetic Weighted Pyramid Operation Tree (GWPOT). Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2014, 29, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behnood, A.; Behnood, V.; Gharehveran, M.M.; Alyamac, K.E. Prediction of the compressive strength of normal and high-performance concretes using M5P model tree algorithm. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 142, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MAlkharisi, K.; Dahish, H.A.; Youssf, O. Prediction models for the hybrid effect of nano materials on radiation shielding properties of concrete exposed to elevated temperatures. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 21, e03750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, K.; Ahmad, W.; Amin, M.N.; Ahmad, A.; Nazar, S.; Alabdullah, A.A.; Arab, A.M.A. Exploring the use of waste marble powder in concrete and predicting its strength with different advanced algorithms. Materials 2022, 15, 4108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.; Yang, M.; Shang, X.; Xiong, Y.; Zhang, Y. Predicting the compressive strength of UHPC with coarse aggregates in the context of machine learning. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 19, e02627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobuz, M.H.R.; Al-Imran; Datta, S.D.; Jabin, J.A.; Aditto, F.S.; Hasan, N.M.S.; Hasan, M.; Zaman, A.A.U. Assessing the influence of sugarcane bagasse ash for the production of eco-friendly concrete: Experimental and machine learning approaches. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 20, e02839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesh, A.C.; Mohana, R.; Loganathan, P.; Kumar, V.M.; Kırgız, M.S.; Nagaprasad, N.; Ramaswamy, K. Development of alkali activated paver blocks for medium traffic conditions using industrial wastes and prediction of compressive strength using random forest algorithm. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 15152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Saleem, M.; Harrou, F.; Sun, Y. Explainable machine learning methods for predicting water treatment plant features under varying weather conditions. Res. Eng. 2024, 21, 101930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.N.; Nassar, R.-U.-D.; Ahmad, M.T.Q.A.; Khan, K.; Javed, M.F. Investigating the compressive property of foamcrete and analyzing the feature interaction using modeling approaches. Res. Eng. 2024, 24, 103305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harirchian, E.; Hosseini, S.E.A.; Novelli, V.; Lahmer, T.; Rasulzade, S. Utilizing advanced machine learning approaches to assess the seismic fragility of non-engineered masonry structures. Res. Eng. 2024, 21, 101750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isleem, H.F.; Chukka, N.D.K.R.; Bahrami, A.; Oyebisi, S.; Kumar, R.; Qiong, T. Nonlinear finite element and analytical modelling of reinforced concrete filled steel tube columns under axial compression loading. Res. Eng. 2023, 19, 101341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaidi, A.; Bichri, A.; Abderafi, S. Efficient machine learning model to predict dynamic viscosity in phosphoric acid production. Res. Eng. 2023, 18, 101024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinkhonde, D.; Bezabih, T.; Mirindi, D.; Mashava, D.; Mirindi, F. Ensemble machine learning algorithms for efficient prediction of compressive strength of concrete containing tyre rubber and brick powder. Clean Waste Syst. 2025, 10, 100236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taiwo, R.; Yussif, A.-M.; Adegoke, A.H.; Zayed, T. Prediction and deployment of compressive strength of high-performance concrete using ensemble learning techniques. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 451, 138808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katlav, M.; Ergen, F.; Donmez, I. AI-driven design for compressive strength of ultra-high performance geopolymer concrete (UHPFC): From explainable ensemble models to the graphical user interface. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 40, 109915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Xu, J.J.; Lin, L.; Yu, Y. Ensemble machine learning models for compressive strength and elastic modulus of recycled brick aggregate concrete. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 41, 110635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Huang, H. Predicting compressive and flexural strength of high-performance concrete using a dynamic Catboost Regression model combined with individual and ensemble optimization techniques. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 38, 108174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, H.J.; Alyami, M.; Nawaz, R.; Hakeem, I.Y.; Aslam, F.; Iftikhar, B.; Gamil, Y. Prediction of compressive strength of two-stage (preplaced aggregate) concrete using gene expression programming and random forest. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 19, e02581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaskar, A.; Alfalah, G.; Althoey, F.; Abuhussain, M.A.; Javed, M.F.; Deifalla, A.F.; Ghamry, N.A. Comparative study of genetic programming-based algorithms for predicting the compressive strength of concrete at elevated temperature. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 18, e02199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golafshani, E.M.; Kim, T.; Behnood, A.; Ngo, T.; Kashani, A. Sustainable mix design of recycled aggregate concrete using artificial intelligence. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 442, 140994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khademi, F.; Jamal, S.M.; Deshpande, N.; Londhe, S. Predicting strength of recycled aggregate concrete using artificial neural network, adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system and multiple linear regression. Int. J. Sustain. Built Environ. 2016, 5, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahish, H.A.; Almutairi, A.D. Compressive strength prediction models for concrete containing nano materials and exposed to elevated temperatures. Result Eng. 2025, 25, 103975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Farooq, F.; Niewiadomski, P.; Ostrowski, K.; Akbar, A.; Aslam, F.; Alyousef, R. Prediction of compressive strength of fly ash based concrete using individual and ensemble algorithm. Materials 2021, 14, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seghier, M.E.A.B.; Golafshani, E.M.; Jafari-Asl, J.; Arashpour, M. Metaheuristicbased machine learning modeling of the compressive strength of concrete containing waste glass. Struct. Concr. 2023, 24, 5417–5440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, M.K.; Qurashi, M.A.; Zhu, X.Y.; Shah, S.A.R.; Siddiq, M.U. A comparative performance analysis of machine learning models for compressive strength prediction in fly ash-based geopolymer concrete using reference data. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 22, e04207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, H.-V.T.; Nguyen, M.H.; Ly, H.-B. Development of machine learning methods to predict the compressive strength of fiber reinforced self-compacting concrete and sensitivity analysis. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 367, 130339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Prado-Gil, J.; Martínez-García, R.; Jagadesh, P.; Juan-Valdes, A.; Gόnzalez-Alonso, M.-I.; Palecia, G. To determine the compressive strength of self-compacting recycled aggregate concrete using artificial neural network (ANN). Ani Shams Eng. J. 2024, 15, 102548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, N.; Kashem, A.; Das, P.; Ali, M.N.; Paul, S. Prediction of high-performance concrete compressive strength using deep learning techniques. Asian J. Civ. Eng. 2024, 25, 327–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Naghi, A.A.A.; Aamir, K.; Amin, M.N.; Iftikhar, B.; Mehmood, K.; Qadir, M.T. Predicting strength in polypropylene fiber reinforced rebberized concrete using symbolic regression AI techniques. Case Stud. Constr. Mat. 2025, 23, e05024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, K.S.; Islam, A.B.M.S. Symbolic regression model for predicting compression strength of prismatic masonry columns confined by FRP. Buildings 2023, 13, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseri, H.; Jahanbakhsh, H.; Hosseini, P.; Nejad, F.M. Designing sustainable concrete mixture by developing a new machine learning technique. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 258, 120578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseri, H.; Jahanbakhsh, H.; Khezri, K.; Javid, A.A.S. Toward sustainability in optimizing the fly ash concrete mixture ingredients by introducing a new prediction algorithm. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 24, 2767–2803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseri, H.; Hosseini, P.; Jahanbakhsh, H.; Hosseini, P.; Gandomi, A.H. A novel evolutionary learning to prepare sustainable concrete mixtures with supplementary cementitious materials. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 25, 5831–5865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamika, W.; Shashika, D.; Nisal, A.; Pamith, R.; Sumudu, H.; Chinthaka, M.; Meddage, D.P.P. Multiscale modelling and explainable AI for predicting mechanical properties of carbon fibre woven composites with parametric microsscale and mesoscale configurations. Compos. Struct. 2025, 369, 11982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shashika, D.; Perampalam, G.; Sumudu, H.; Meddage, D.P.P.; James, B.P.L. Data-informed design equation based on numerical modelling and interpretable machine learning for the shear capacity of cold-formed steel hollow flange beams with unstiffened and edge stiffened openings. Structures 2025, 81, 110397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, R.Z. Research on the Construction of a Prediction Model for the 28-Day Compressive Strength of Freshly Mixed Concrete. Master’s Thesis, Nanchang Institute of Technology, Nanchang, China, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shashikant, K.; Rakesh, K.; Baboo, R.; Pijush, S. Prediction of compressive strength of high-volume fly ash self-compacting concrete with silica fume using machine learning techniques. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 438, 136933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.S.; Jiang, M.Y.; Tang, M.X.; Liang, H.Q.; Cui, H.; Liu, C.L.; Ji, C.J.; Wang, Y.Z.; Jian, S.M.; Wei, C.H.; et al. Prediction of compressive strength of fly ash-based geopolymers concrete based on machine learning. Res. Eng. 2025, 27, 106492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, J.G.; Zaman, A.; Farooq, F. Machine learning-based prediction of compressive strength in sustainable self-compacting concrete. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 161, 112190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, K.; Rafique, F.; Naseem, Z.; Alqahtani, F.K.; Zafar, I.; Ju, M. Machine learning and multicriteria analysis for prediction of compressive strength and sustainability of cementitious materials. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 21, e04080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, N.; Friedman, J.; Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R. Regularization paths for cox’s proportional hazards model via coordinate descent. JSS J. Stat. Soft. 2011, 39, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.K.; Gao, R.; Ganaie, M.A.; Tanveer, M.; Suganthan, P.N. Random vector functional link network: Recent developments, applications and future directions. Appl. Soft. Comput. 2023, 143, 110377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyelowe, K.C.; Kamchoom, V.; Ebid, A.M.; Hanandeh, S.; LIamuca, J.L.L.; Yachambay, F.P.L.; Palta, J.L.A.; Vishnupriyan, M.; Avudaiappan, S. Optimizing the utilization of metakaolin in pre-cured geopolymer concrete using ensemble and symbolic regressions. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 6858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Őzkilic, Y.O.; Zeybek, O.; Bahrami, A.; Celik, A.I.; Mydin, M.A.O.; Karalar, M.; Hakeem, I.Y.; Roy, K.; Jagadesh, P. Optimum usage of waste marble powder to reduce use of cement toward eco-friendly concrete. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 25, 4799–4819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.A.; Sagong, M.J.; Jung, J.; Kim, E.S.; Kim, H.S. Explainable machine learning for understanding and predicting geometry and defect types in Fe-Ni alloys fabricated by laser metal deposition additive manufacturing. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 22, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekanayake, I.U.; Meddage, D.P.P.; Rathnayake, U. A novel approach to explain the black-box nature of machine learning in compressive strength predictions of concrete using Shapley additive explanations (SHAP). Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 16, e01059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaaban, M.; Amin, M.; Selim, S.; Riad, I.M. Machine learning approaches for forecasting compressive strength of high-strength concrete. SCI Rep. 2025, 15, 25567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.F.; Wang, X. Bayesian optimization of stacking ensemble learning model for HPC compressive strength prediction. Expert. Syst. Appl. 2025, 288, 128281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.H.; Liu, W.S.; Zhou, P.; Wu, A.P.O. Predicting the Compressive Strength of Recycled Concrete Using Ensemble Learning Model; Digital Object Identifier; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, F.; Li, H.Y. A two-level machine learning prediction approach for RAC compressive strength. Buildings 2024, 14, 2885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Yao, T.; Yue, J.; Wang, M.; Xia, S. Compressive strength prediction of BFRC based on a novel hybrid machine learning model. Buildings 2023, 13, 1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migallón, V.; Penadés, H.; Penadés, J.; Tenza-Abril, A.J. A machine learning approach to prediction of the compressive strength of segregated lightweight aggregate concretes using ultrasonic pulse velocity. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Sun, Y.; Jiao, W.; Zheng, J.; Li, Z.; Zhang, S. Prediction of compressive strength and elastic modulus for recycled aggregate concrete based on AutoGluon. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhong, Y.; Liao, G.; Ding, Q.; Zhang, T.; Li, X. Prediction of compressive strength of concrete specimens based on interpretable machine learning. Materials 2024, 17, 3661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, G.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, X. Predicting the compressive strength of environmentally friendly concrete using multiple machine learning algorithms. Buildings 2024, 14, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, K.L.; Xie, S.; Ghannam, M.; Guan, M.; Ning, N.; Li, Y.; Zhang, C. Strength prediction and correlation of cement composites: A cross-disciplinary approach. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 41746–41756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, W.; Zhu, Z.; Sun, H.; Ma, B.; Yang, L. Development of machine learning models for the prediction of the compressive strength of calcium-based geopolymers. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 380, 135159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iftikhar, B.; Alih, S.C.; Vafaei, M.; Elkotb, M.A.; Shutaywi, M.; Javed, M.F.; Deebani, W.; Khan, M.I.; Aslam, F. Predictive modeling of compressive strength of sustainable rice husk ash concrete: Ensemble learner optimization and comparison. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 348, 131285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaia, G.C.; Gastaldini, A.L.G.; Moraes, R. Physical and pozzolanic action of mineral additions on the mechanical strength of high-performance concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2003, 25, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, R.; Li, B.; Elamin, A.; Wang, S.; Tsioulou, O.; Wanatowski, D. Experimental investigation of properties of concrete containing recycled construction wastes. Int. J. Civ. Eng. 2018, 16, 1621–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knaack, A.M.; Kurama, Y.C. Design of concrete mixtures with recycled concrete aggregates. Acids Mater. J. 2013, 110, 483–493. [Google Scholar]

- Meddah, M.S.; Zitouni, S.; Belâabes, S. Effect of content and particle size distribution of coarse aggregate on the compressive strength of concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2010, 24, 505–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokuolu, O.A.; Olaniyi, T.B.; Jacob-Oricha, S.O. Evaluation of calcium carbide residue waste as a partial replacement for cement in concrete. J. Solid. Waste Technol. Manag. 2018, 44, 370–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, P.; Sarker, P. Effect of fly ash on the durability properties of high strength concrete. Procedia Eng. 2011, 14, 1149–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.-H.; Tong, K.T.; Lee, S.; Karamanli, A.; Vo, T.P. Prediction compressive strength of cement-based mortar containing meta-kaolin using explainable Categorical Gradient Boosting model. Eng. Struct. 2022, 269, 114768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.J.; Peethamparan, S. Stepwise regression modeling for compressive strength of alkali-activated concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 141, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winnefeld, F.; Becker, S.; Pakusch, J.; Gotz, T. Effects of the molecular architecture of comb-shaped superplasticizers on their performance in cementitious systems. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2007, 29, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.S.; Kim, Y.J.; Cho, J.R.; Jeon, S.J. Early-age strength of ultra-high performance concrete in various curing conditions. Materials 2015, 8, 5537–5553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topçu, I.B.; Toprak, M.U. Fine aggregate and curing temperature effect on concrete maturity. Cem. Concr. Res. 2005, 35, 758–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakir, N. Experimental study of the effect of curing mode on concreting in hot weather. J. Compos. Adv. Mater. 2021, 31, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berhane, Z. The behaviour of concrete in hot climates. Mater. Struct. 1992, 25, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, F.; Liu, X.; Li, J. Temperature effect modeling in structural health monitoring of concrete dams using kernel extreme learning machines. Struct. Health Monit. 2020, 19, 987–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naas, A.; Taha-Hocine, D.; Salim, G.; Michele, Q. Combined effect of powdered dune sand and steam-curing using solar energy on concrete characteristics. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 322, 126474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastrup, E. Heat of hydration in concrete. Mag. Concr. Res. 1954, 6, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soutsos, M.; Hatzitheodorou, A.; Kwasny, J.; Kanavaris, F. Effect of in situ temperature on the early age strength development of concretes with supplementary cementitious materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 103, 505–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feri, K.; Kumar, V.S.; Romi, A.; Gotovac, H. Effect of aggregate size and compaction on the strength and hydraulic properties of pervious concrete. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Medeiros-Junior, R.A.; de Lima, M.G.; Oliveira, A. Influence of different compacting methods on concrete compressive strength. Matéria 2018, 23, e12152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, S.; Ransinchung, G.D.R.N. Performance evaluation and sustainability assessment of precast concrete paver blocks containing coarse and fine RAP fractions: A comprehensive comparative study. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 300, 124042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahdeo, S.K.; Chandrappa, A.; Biligiri, K.P. Effect of compaction type and compaction efforts on structural and functional properties of pervious concrete. Transp. Dev. Econ. 2021, 7, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, R.; Lapeyre, J.; Ma, H.; Kumar, A. Prediction of compressive strength of concrete: Critical comparison of performance of a hybrid machine learning model with standalone models. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2019, 31, 04019255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, B.A.; Hall, A.; Pilon, L.; Gupta, P.; Sant, G. Can the compressive strength of concrete be estimated from knowledge of the mixture proportions? New insights from statistical analysis and machine learning methods. Cem. Concr. Res. 2019, 115, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Akber, M.Z.; Poon, C.S.; Zheng, W. Predicting the 28-day compressive strength by mix proportions: Insights from a large number of observations of industrially produced concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 400, 132754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Akber, M.Z.; Zheng, W. Prediction of seven-day compressive strength of field concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 305, 124604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaabene, W.B.; Flah, M.; Nehdi, M.L. Machine learning prediction of mechanical properties of concrete: Critical review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 260, 119889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.; El-hassan, K.A.; Shaaban, M.; Mashaly, A.A. Effect of waste tea ash and sugar beet waste ash on green high strength concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 495, 143611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizamir, M.; Wang, M.; Ikram, R.M.A.; Gholampour, A.; Ahmed, K.O.; Heddam, S.; Kim, S. An interpretable XGBoost-SHAP machine learning model for reliable prediction of mechanical properties in waste foundry sand-based eco-friendly concrete. Result Eng. 2025, 25, 104307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, I.-C. Modeling of strength of high-performance concrete using artificial neural networks. Cem. Concr. Res. 1998, 28, 1797–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.Y.; Zhang, L.J.; Lu, J.Y.; Yan, Z.Q. Research on design parameters of mix proportion for recycled aggregate concrete. J. Archit. Civ. Eng. 2016, 33, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

| Authors | ML/DL Methods | Input Parameters | Data Source | R2 | Research Object | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chithra et al. [9] | ANN, MRA | Cement, aggregate ratios, curing time, temperature, density, moisture content | Laboratory experiments | 0.9975 for ANN, 0.6374–0.6717 for MRA | Compressive strength of concrete | ANN outperforms MRA in accuracy for complex |

| Dahish et al. [10] | MNLR, SVM, ANN | Material proportion, chemical composition, relative importance rankings | Experiments and the literature | 0.8898 for MNLR1 Fc28 0.9015 for MNLR2 Fc180 | Compressive strength prediction of cement mortars | Applies support vector machine (SVM) to predict the compressive strength of cement mortar containing NP and SF, expanding the application scenarios of machine learning in the field of building materials |

| Sonebi et al. [17] | SVM | Cement, limestone powder, water, sand, coarse aggregate, superplasticizer (kg/m3), and testing time | Experiments | Polynomial kernel SVM yielded lower R2 values | Prediction of fresh properties of self-compacting concrete (SCC) | Provided an alternative method to simulate tailor-made SCC mixes, reducing the need for extensive trial batches in practice |

| Nyirandayisabye et al. [18] | LR, SVR, RF, KNN, GBR, LGBM | OT, AEBO, OAVP, EPT, EPBM, EPSM, MSR, OBG, OAG | Michigan Department of Transportation and Michigan State University | GBR achieved the highest R2 of 99%, followed by LGBM (98%), stacking regressor and DTR (97%), RFR (95%), LR (64%), and poor performance by KNN and SVR (≈1% or negative R2) | Predict multiple types of asphalt pavement damage | Addressed the lack of comparative studies on ML algorithms for detecting combined pavement damage types |

| Cheng et al. [19] | ANN, MRA, MNLR, SVM, etc. | Concrete and asphalt pavement | Literature and experimental data, institutional datasets | ANN (0.9975), GBR (99%), LGBM (98%) | Compressive strength, asphalt pavement damage prediction | Proposed Genetic Weighted Pyramid Operation Tree (GWPOT) outperformed traditional Operation Tree (OT) |

| Behnood et al. [20] | M5P | Concrete, constituents, ratios, age | 1912 data collected from the published literature | 0.911 | Compressive strength of NC and HPC | Log transformation for non-linearity |

| Alkharisi et al. [21] | LR, M5P, RF, XGBoost | NA dosage, CNTs dosage, temperature, heating duration | 117 experimental data points from cubic concrete specimens exposed to elevated temperatures. Data were sourced from the previously published literature | 0.5962 for LR, 0.7895 for M5P, 0.9732 for RF, 0.9898 for XGBoost | Predict the gamma-ray radiation shielding properties (LAC) of nano-modified concrete (NMC) incorporating NA and CNTs, subjected to elevated temperatures | First study to model the combined influence of NA and CNTs on LAC under high temperatures |

| Golafshani et al. [38] | Various ML techniques (stacking ensemble) | Ingredient quantities; aggregate properties; cement grade (CG); TA | 3519 RAC mixtures were compiled from 120 peer-reviewed scientific studies | Boosting models R2 > 0.99; stacking model R2 = 0.9587 | CS of RAC | Stacking improved model accuracy; sensitivity analysis highlighted concrete TA and cement content as critical factors |

| Muhammad et al. [43] | MLR, ANN, SVM, KNN, DT | FA, sand, CA, SS, NaOH, water, alkaline activator solution, molarity, water–binder ratio (w/c), silica–alumina ratio (Si/Al), curing age, and curing temperature | 563 samples collected from 55 literature studies spanning over 20 years | ANNs > boosting DT > bootstrap DT > SVMs > DT > KNNs > MLR, 0.92 for ANNs (highest performance) | Concrete CS | Shapley additive model explanation identified significant influence factors on CS |

| Mai et al. [44] | DT, LGBM, XGBoost | Cement, coarse aggregate, fine aggregate, water, supplementary materials, fibers, admixtures | 387 data samples collected from 11 international publications | XGBoost R2 = 0.992; DTR2 = 0.986; LGBM R2 = 0.931 | CS of FRSCC | Achieved high predictive performance and stability; sensitivity analysis revealed cement, CA, fine aggregate, water, and sample age as significant factors |

| Jesús et al. [45] | ANN | Cement, admixtures, water, fine aggregate, coarse aggregate, fine aggregate, superplasticizer, percentage of recycled aggregate | 515 mix designs are collected from the existing literature | Family I: R2 = 0.9299; Family II: R2 = 0.824; Family III: R2 = 0.8775; Family IV: R2 = 0.7991 | 28-day CS of self-consolidating concrete (including RAC) | Developed a prediction equation |

| Parameter | Unit | Type | Minimum | Mean | Maximum | Std | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | kg/m3 | Input | 102 | 281.17 | 540 | 104.51 | 0.51 | −0.52 |

| Sl | kg/m3 | Input | 0 | 73.9 | 359.4 | 86.28 | 0.8 | −0.51 |

| FA | kg/m3 | Input | 0 | 54.19 | 200.1 | 64 | 0.54 | −1.33 |

| W | kg/m3 | Input | 121.8 | 181.57 | 247 | 21.36 | 0.07 | 0.122 |

| SP | kg/m3 | Input | 0 | 6.2 | 32.2 | 5.97 | 0.91 | 1.411 |

| CA | kg/m3 | Input | 801 | 972.92 | 1145 | 77.75 | −0.04 | −0.6 |

| NFA | kg/m3 | Input | 594 | 773.58 | 992.6 | 80.18 | −0.25 | −0.1 |

| TA | Day (1–365) | Input | 1 | 45.66 | 365 | 63.17 | 3.27 | 12.17 |

| CS | MPa | Output | 2.33 | 35.82 | 82.6 | 16.71 | 0.42 | −0.31 |

| Models | Optimal Hyperparameters |

|---|---|

| Elastic net regression | α = 0.003, R = 0.1 |

| KNN | Power parameter = “Euclidean distance”, K = 6 |

| ANN | Hidden layer size = (128, 64), activation = ‘ReLU’, optimization algorithm = ‘adam’, initial learning rate = 1 × 10−3, dropout = 0.2, batch size = 64, patience = 20 |

| SVR | Kernel = radial basis function, γ = ‘scale’, regularization parameter = 297, ε = 2.50 |

| RF | Maximum depth = 40, minimum samples leaf = 1, minimum samples split = 5, number of estimators = 500 |

| XGBoost | Subsample ratio = 0.8585, γ = 0.9757, learning rate range = 0.12, maximum tree depth = 3, number of estimators = 900, L1 regularization term = 0.3749, L2 regularization term = 0.8558 |

| CatBoost | Bagging temperature = 5.8, depth = 7, iterations = 300, L2 regulation term = 3, learning rate = 0.1, random strength = 1.0, subsample ratio = 0.8 |

| Symbolic regression | Population size = 500, generations = 20, stopping criteria = 0.01, crossover probability = 0.7, subtree mutation probability = 0.1, hoist mutation probability = 0.05, point mutation probability = 0.1, max samples = 0.9 |

| Errors | Phases | Elastic Net Regression | KNN | ANN | SVR | RF | XGBoost | Catboost | Symbolic Regression |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE (MPa) | Training | 10.36 | 7.47 | 4.6 | 3.73 | 3.14 | 1.57 | 1.47 | 8.45 |

| MAE (MPa) | 8.19 | 5.7 | 3.4 | 2.8 | 2.38 | 0.97 | 1.09 | 6.58 | |

| MAPE (%) | 31.51 | 22.01 | 11.84 | 10.15 | 8.98 | 3.43 | 3.80 | 23.62 | |

| R2 | 0.62 | 0.8 | 0.93 | 0.95 | 0.97 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.74 | |

| SI | 0.29 | 0.21 | 0.13 | 0.1 | 0.91 | 0.04 | 0.96 | 0.72 | |

| RMSE (MPa) | Testing | 10.46 | 8.6 | 5.68 | 5.94 | 5.72 | 4.34 | 4.85 | 9.99 |

| MAE (MPa) | 8.33 | 6.34 | 4.3 | 4.28 | 4.29 | 2.82 | 2.83 | 7.53 | |

| MAPE (%) | 32.55 | 23.37 | 13.94 | 14.58 | 15.14 | 9.29 | 9.79 | 25.44 | |

| R2 | 0.6 | 0.65 | 0.85 | 0.85 | 0.88 | 0.90 | 0.92 | 0.68 | |

| SI | 0.3 | 0.27 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.82 | 0.12 | 0.89 | 0.68 |

| Stacking Models | Individual ML Models (Used) | Training Set | Testing Set | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ElasticNet | KNN | ANN | SVR | RF | XGBoost | CatBoost | Symbolic Regression | RMSE (MPa) | MAE (MPa) | MAPE (%) | R2 | SI | RMSE (MPa) | MAE (MPa) | MAPE (%) | R2 | SI | |

| Stacking-2 | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | √ | √ | □ | 1.4225 | 0.8685 | 3.2123 | 0.9928 | 0.0402 | 4.5115 | 2.9161 | 8.8894 | 0.9258 | 0.1226 |

| Stacking-3 | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | √ | √ | √ | 1.4271 | 0.8752 | 3.2168 | 0.9927 | 0.0403 | 4.5217 | 2.9172 | 8.8957 | 0.9255 | 0.1229 |

| Stacking-4 | □ | □ | □ | □ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 1.4271 | 0.8752 | 3.2168 | 0.9927 | 0.0403 | 4.5217 | 2.9172 | 8.8957 | 0.9255 | 0.1229 |

| Stacking-5 | □ | □ | □ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 1.449 | 0.8965 | 3.3161 | 0.9925 | 0.0409 | 4.5206 | 2.9215 | 8.9135 | 0.9255 | 0.1229 |

| Stacking-6 | □ | □ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 1.449 | 0.8965 | 3.3161 | 0.9925 | 0.0409 | 4.5206 | 2.9215 | 8.9135 | 0.9255 | 0.1229 |

| Stacking-7 | □ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 1.4462 | 0.891 | 3.309 | 0.9925 | 0.0408 | 4.5133 | 2.9211 | 8.9241 | 0.9257 | 0.1227 |

| Stacking-8 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 1.4448 | 0.8894 | 3.2959 | 0.9925 | 0.0408 | 4.5146 | 2.9207 | 8.9223 | 0.9257 | 0.1227 |

| Reference | Material Used | Predicted Properties | ML Algorithm | Reported R2 Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current Study | UCI dataset and other 952 data samples collected from various sources | CS | XGBoost, CatBoost | 0.99 |

| Golafshani et al. [38] | 3519 data samples collected from various sources | CS | XGBoost, LightBoost, CatBoost | 0.9587 |

| Li and Wang [66] | 400 data samples obtained from the literature | CS | RF, CatBoost | 0.97 |

| Pan et al. [67] | UCI dataset and 63 samples of 2 different RAC | CS | XGBoost, DT, ET | 0.985 |

| Qi and Li [68] | 1100 experimental database | CS | XGBoost, LightBoost | 0.964 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, J.; Guan, D.; Liu, X. Comparative Performance Analysis of Machine Learning Models for Compressive Strength Prediction in Concrete Mix Design. Math. Comput. Appl. 2025, 30, 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/mca30060128

Liu J, Guan D, Liu X. Comparative Performance Analysis of Machine Learning Models for Compressive Strength Prediction in Concrete Mix Design. Mathematical and Computational Applications. 2025; 30(6):128. https://doi.org/10.3390/mca30060128

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Junyu, Dayou Guan, and Xi Liu. 2025. "Comparative Performance Analysis of Machine Learning Models for Compressive Strength Prediction in Concrete Mix Design" Mathematical and Computational Applications 30, no. 6: 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/mca30060128

APA StyleLiu, J., Guan, D., & Liu, X. (2025). Comparative Performance Analysis of Machine Learning Models for Compressive Strength Prediction in Concrete Mix Design. Mathematical and Computational Applications, 30(6), 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/mca30060128