Abstract

Differential eigenvalue problems arise in many fields of Mathematics and Physics, often arriving, as auxiliary problems, when solving partial differential equations. In this work, we present a method for eigenvalues computation following the Tau method philosophy and using Tau Toolbox tools. This Matlab toolbox was recently presented and here we explore its potential use and suitability for this problem. The first step is to translate the eigenvalue differential problem into an algebraic approximated eigenvalues problem. In a second step, making use of symbolic computations, we arrive at the exact polynomial expression of the determinant of the algebraic problem matrix, allowing us to get high accuracy approximations of differential eigenvalues.

MSC:

34B09; 34L15; 65L15

1. Introduction

Finding eigenfunctions of differential problems can be a hard task, at least for some classical problems. Among others, we can find literature in Sturm–Liouville problems, in Mathieu problems or in Orr–Sommerfeld problems describing the difficulties involved in the resolution of those problems [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. The first difficulty consists of finding accurate numerical approximations for the respective eigenvalues.

In this work, we present a procedure based on the Ortiz and Samara’s operational approach to the Tau method described in [9], where the differential problem is translated into an algebraic problem. This is achieved using the called operational matrices that represent the action of differential operators in a function. We have deduced explicit formulae for the elements of these matrices [10,11] obtained by performing operations on the bases of orthogonal polynomials and, for some families, we have exact formulae, which enables the construction of very accurate operational matrices. The Tau method has already been used for these kinds of problems [5,9,12,13]; however, our work on matrix calculation formulas adds efficiency and precision to the method.

Our main purpose is to use the Tau Toolbox, a Matlab numerical library that is being developed by our research group [14,15,16]. This library allows a stable implementation of the Tau method for the construction of accurate approximate solutions for integro-differential problems. In particular, the construction of the operational matrices is done automatically. These facts led us to think that the Tau Toolbox seems to be useful for these kinds of problems.

Finally, operating with symbolic variables, we define the determinant of those matrices as polynomials and use its roots as eigenvalues’ approximations.

We present some examples showing that, using this technique in the Tau Toolbox, we are able to obtain results comparable with those reported in the literature and sometimes even better.

2. The Tau Method

Let be an order differential operator, where and are some function spaces, and let be functionals representing boundary conditions, so that

is a well posed differential problem.

2.1. The Tau Method Principle

A particular implementation of the Tau method depends on the choice of an orthogonal basis for . A sequence of orthogonal polynomials with respect to the weight function on a given interval of orthogonality satisfies

where and is the Kronecker delta [17].

Let be the space of algebraic polynomials of any degree and let us suppose that is dense in ; then, the solution y of (1) has a series representation . A polynomial approximation of degree is achieved by

where and .

2.2. Operational Formulation

For a given , we define the matrix

and the vector

If, in problem (1), the differential operator is linear and the are linear functionals, then problem (3) can be put in matrix form as

The matrix , called the Tau matrix, can be evaluated from operational matrices, that is, matrices translating into coefficients vectors the action of a differential operator in a function y.

Proposition 1.

Let be an orthogonal polynomial basis, and infinite matrices such that

Then, for each ,

Proof.

For , the result is true by hypothesis. Now, supposing that (5) is true for a , then

and

ending the proof by induction. □

The following result generalizes the algebraic representation from the previous proposition to differential operators.

Corollary 1.

Let be a linear differential operator with polynomial coefficients

and let .

If , then with

where when , and denotes the main block of the matrix with .

In [9], the authors discussed the application of this operational formulation of the Tau method to the numerical approximation of eigenvalues defined by differential equations. They proved that, for a differential eigenvalue problem, where in (1)

and is a parameter, the zeros of approach the eigenvalues of (1).

2.3. Tau Matrices’ Properties

Given that we are dealing with a general orthogonal polynomial basis, instead of particular cases like Chebyshev or Legendre, we can only make assumptions about general properties of Tau matrices . Anyway, we can’t expect to have symmetric matrices and, in general, they can be considered sparse but with a low level of sparsity.

Since in Proposition 1 is an orthogonal basis, then is the tridiagonal matrix with the coefficients of its three term recurrence relation. Therefore, for problems with polynomial coefficients, matrices of Corollary 1 are banded matrices, with all non-zero elements between the diagonals.

Matrices are always strictly upper triangular and so are upper Hessenberg matrices. The resulting block of defined in (4) is a general h upper Hessenberg matrix.

Moreover, one advantage of the Tau method is its ability to deal with boundary conditions, allowing the treatment of any linear combination of values of y and of its derivatives for in (1). Thus, the block in is usually dense, with its entries , made by linear combinations of orthogonal polynomial values and of its derivatives , in prescribed abscissas .

Assembling those blocks and in , we get an upper Hessenberg matrix.

For some problems, whose dependence on the eigenvalues is verified only in the differential equation, we can use Schur complements to reduce matrix sizes. Considering matrix in (4) partitioned as

where is and the other blocks are partitioned accordingly. If is non-singular, then

and the problem is reduced to solve

reducing to the problem dimension. In the worst case, when is singular, we have to work with the matrix .

In the following sections, we illustrate the application of the Tau method to approximate eigenvalues in some classical problems.

3. Problems with Polynomial Coefficients

Sturm–Liouville problems arise from vibration problems in continuum mechanics. The general form of a fourth order Sturm–Liouville equation is

with appropriate initial and boundary conditions, where , , and are given piecewise continuous functions, with and . These conditions mean that (8) has an infinite sequence of real eigenvalues, bounded from above, and each one has multiplicity of at most 2 [1].

If p and q are differentiable functions, it is an elementary task to give (8) the form

From this equation, we derive the operational matrix for the general form of the fourth order Sturm–Liouville differential operator associated with (8)

Assuming that coefficients , and are polynomials, or convenient polynomial approximations of the coefficient functions, then the height of this differential operator is well defined as

where is the polynomial degree. One consequence of Corollary 1 is that to evaluate the block in (4) we have to apply (9) with and truncated to its first lines and columns.

The Tau matrix of a fourth order Sturm–Liouville problem is the matrix , where is the matrix representing boundary conditions and is the first main block of .

Example 1.

Consider the Sturm–Liouville boundary value problem

whose exact eigenvalues satisfy [1,2]

In that case , where I is the identity matrix, and the boundary conditions can be represented by , where and are length n line vectors with the polynomial base values in the boundary domain.

For each , in (7) is an square matrix and its determinant an degree polynomial. We use the Matlab function roots to find its zeros and we inspect their accuracy by testing if they satisfy relation (11).

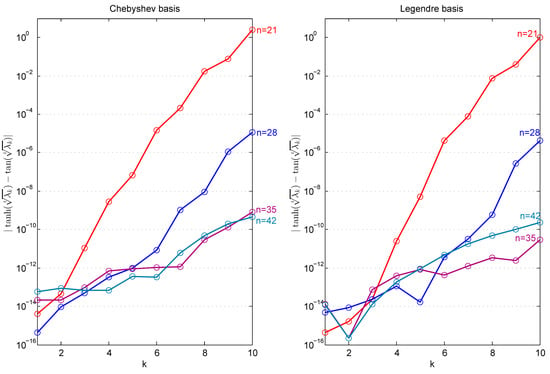

In Figure 1, we present for the first 10 eigenvalues approximations obtained with and , with Chebyshev and Legendre bases shifted to .

Figure 1.

, being the roots of in Example 1.

Example 2.

A very similar problem, presented as the clamped rod problem in [12,18], is

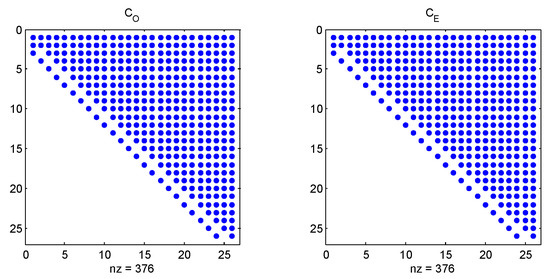

In that case, and whenever we have a symmetric problem and a symmetric base, the matrix in (7) has zeros intercalating all non-zero elements. We can reduce the problem dimension, defining two matrices and with respectively the odd and the even entries of , then . In that case, since is an 4-upper Hessenberg matrix, and are 2-upper Hessenberg matrices. The sparsity pattern of those two matrices, in Legendre basis and with , are showed in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Sparsity pattern of and with in Legendre base, for Example 2.

The first 14 eigenvalues, evaluated with an matrix, are presented in [12]. In Table 1, we compare those values with our results in the Legendre basis and with and . We present values of , which allows us to verify that our estimates satisfy the property that the kth eigenvalue is proportional to [18].

Table 1.

Eigenvalues of Example 2 presented in [12] and with and in Legendre basis.

Example 3.

Consider the following Sturm–Liouville problem with non-null q and r coefficients

with constants .

The operational matrix (9) for this case is

and , with the same and vectors of the previous example.

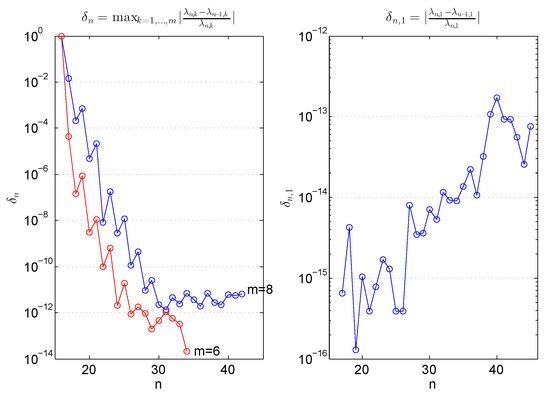

If is the kth root of , and considering as an estimative of the relative error in , then is an estimative of the maximum relative error in the first m eigenvalues of the problem. In Figure 3 left, we present , with and with for Example 3 with and for . In Figure 3 right, the absolute relative error in the lowest eigenvalue is presented for the same n values.

Figure 3.

and , (left) and (right), in Example 3.

In Table 2, we compare our results with those of [2] for the first six eigenvalues, and of [8] for the first 4, obtained with values and .

Table 2.

Eigenvalues of Example 3 presented in [8] and [2] and with .

Example 4.

Now, we consider the Orr–Sommerfeld problem

with fixed constants and function U.

The particular case is the Poiseuille flow and, with and was treated in [3,4,5,12]. The operational matrix in that case is

Like in Example 2, this is an upper Hessenberg matrix with zeros intercalating its non-zero elements and we can reduce the problem dimension, splitting in two matrices the Schur complement of the resulting Tau matrix . Choosing Chebyshev basis, this is the operational version of the Tau procedure of [5], where the author was confined to eigenvalues associated with symmetric eigenfunctions, which is equivalent to finding the eigenvalues of .

In [5], the author obtained for as an 8 decimal places exact value for the most unstable mode of this problem. Working with double-precision arithmetic, we obtain . This value results with that is an matrix , the same dimension used in [5].

In addition, with , the smallest value of R for which an unstable eigenmode exists [5], and , we get the results presented in Table 3, together with those of [5].

Table 3.

Values of of Example 4 with critical values and .

4. Non-Polynomial Coefficients

In the previous section, we solved problems in the conditions of Corollary 1, i.e., with differential operators acting in polynomial spaces. In a more general situation, if some of the coefficients in (6) are non-polynomial functions, then the corresponding matrices are functions of instead of polynomial expressions.

If a non-polynomial function in (6) can be defined implicitly by a differential problem, with polynomial coefficients, then we can first of all use the Tau method to find a polynomial approximation to and use to approximate the matrix .

Example 5.

Mathieu’s equation appears related to wave equations in elliptic cylinders [19]. For an arbitrary parameter q, the problem is to find the values of λ for which non-trivial solutions of

exist with prescribed boundary conditions.

It can be shown that there exists a countably infinite set of eigenvalues associated with even periodic eigenfunctions and a countably infinite set of eigenvalues associated with odd periodic eigenfunctions [19]. We are interested in reproducing some of those values given in there.

The operational matrix for problem (15) is

Our first step to approximate Mathieu’s eigenvalues is to approximate matrix . This can be done by, firstly, considering the function as the solution of a differential problem, using Tau method to get a polynomial approximation . In a second step, the operational matrix is approximated by

and, finally, the last step consists in building the Tau matrix and evaluating the zeros of its determinant.

We take integer values and boundary conditions to get for even r, for odd r, and to get for odd r and for even r.

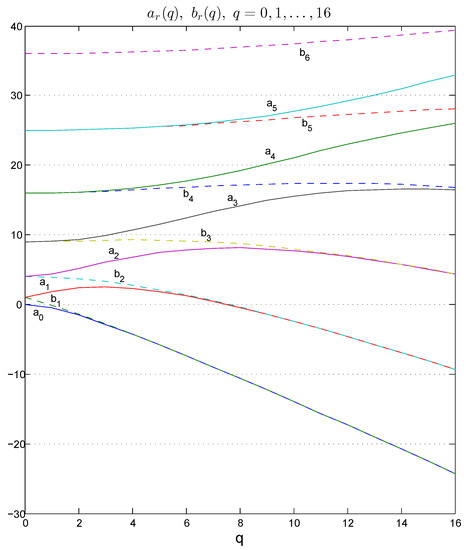

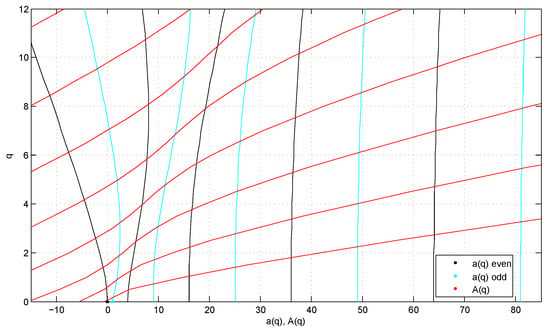

In Figure 4, we show Mathieu eigenvalues and . Values were obtained with a 18th degree polynomial approximation and a Tau matrix in Chebyshev polynomials.

Figure 4.

Mathieu eigenvalues and , for in Example 5.

We can observe, as pointed out in [19], that, for a fixed , we have and that approach as q approaches zero.

Example 6.

Mathieu’s equation also appears coupled with a modified Mathieu’s equation in systems of differential equations as multi parameter eigenvalues problems. The particular case

is studied in [6,7] associated with the eigenfrequencies of an elliptic membrane with semi axes and .

To approximate eigenvalues for this problem, we first have to approximate and by polynomials. Considering, as in the previous example, the 16th degree Tau solution of

and as the same degree Tau solution of

then

and

are matrices approximating the operational matrices associated with differential equations (16).

For each fixed q, we define matrices Tau and , representing Mathieu and modified Mathieu equations, respectively. Defining the nth eigenvalue of , in ascending order, and the mth eigenvalue of , in descending order, in [6], it was proved that and are analytical functions of q. Moreover, for each pair , it was proved the existence and uniqueness of an intersection point of curves and . Those intersections identify the eigenmodes of the elliptic membrane.

In Figure 5, we recover, and extend, figures presented in [6] and in [7]. Intersection points of , the almost vertical curves, and , the oblique curves, are the eigenpairs of (16).

Figure 5.

Mathieu eigenvalues and , for in Example 5. Only values are presented.

5. Nonlinear Eigenvalues Problem

In some differential problems, the eigenvalues can arise in a nonlinear relation with eigenfunctions. Let us consider the following second order problem, related to Weber’s equation:

Example 7.

The operational matrix corresponding to the differential equation is

and so is a polynomial with degree in .

In Table 4, we present the 10 eigenvalues closest to zero, obtained with and with . We can verify that .

Table 4.

Eigenvalues of Example 7 with and . Decimal places presented are those that coincide, until to the first distinct two.

6. Conclusions

Since the pioneering works of Orzag [5] and Ortiz and Samara [9], the Tau method has been scarcely used to solve differential eigenvalues’ problems. With our work, we conclude that the Tau method is a competitive one if we want to evaluate with high accuracy the first eigenvalues, in a large kind of differential problem.

Author Contributions

Formal analysis, J.M.A.M. and M.J.R.; Investigation, J.M.A.M. and M.J.R.; Writing—original draft, J.M.A.M. and M.J.R.; Writing—review and editing, J.M.A.M. and M.J.R.

Funding

This research was partially supported by CMUP (UID/ MAT/ 00144/ 2019), which is funded by FCT (Portugal) with national (MEC) and European structural funds through the programs FEDER, under the partnership agreement PT2020.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Attili, B.S.; Lesnic, D. An efficient method for computing eigenelements of Sturm–Liouville fourth-order boundary value problems. Appl. Math. Comput. 2006, 182, 1247–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzana, H.; Islam, M.S.; Bhowmik, S.K. Computation of Eigenvalues of the Fourth Order Sturm–Liouville BVP by Galerkin Weighted Residual Method. J. Adv. Math. Comput. Sci. 2015, 9, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, S.C.; Schmid, P.J.; Henningson, D.S. Pseudospectra of the Orr–Sommerfeld Operator. SIAM J. Appl. Math. 1993, 53, 15–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop, I.S.; Gheorghiu, C.I. A Chebyshev–Galerkin Method for Fourth Order Problems. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Approximation and Optimization, Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 29 July–1 August 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Orzag, S.A. Accurate solution of the Orr–Sommerfeld stability equation. J. Fluid Mech. 1971, 50, 689–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, A. Eigenmodes and eigenfrequencies of vibrating elliptic membranes: A Klein oscillation theorem and numerical calculations. Commun. Pure Appl. Anal. 2009, 9, 611–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheorghiu, C.I.; Hochstenbach, M.E.; Plestenjak, B.; Rommes, J. Spectral collocation solutions to multiparameter Mathieu’s system. Appl. Math. Comput. 2012, 218, 11990–12000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanane, B. Accurate solutions of fourth order Sturm–Liouville problems. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2010, 234, 3064–3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, E.L.; Samara, H. Numerical solution of differential eigenvalue problems with an operational approach to the Tau method. Computing 1983, 31, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, J.M.A.; Rodrigues, M.J.; Matos, J.C. Explicit formulae for derivatives and primitives of orthogonal polynomials. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1703.00743v2. [Google Scholar]

- Matos, J.M.A.; Rodrigues, M.J.; Matos, J.C. Explicit Formulae for Intergral-Differential Operational Matrices. submitted for publication. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gheorghiu, C.I. Spectral Methods for Differential Problems; Institute of Numerical Analysis: Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Charalambides, M.; Waleffe, F. Gegenbauer Tau Methods with and without Spurious Eigenvalues. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 2008, 47, 48–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Trindade, M.; Matos, J.; Vasconcelos, P.B. Towards a Lanczos Tau-Method Toolkit for Differential Problems. Math. Comput. Sci. 2016, 10, 313–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trindade, M.; Matos, J.; Vasconcelos, P.B. Dealing with functional coefficients within Tau method. Math. Comput. Sci. 2018, 12, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, P.B.; Matos, J.; Trindade, M.S. Spectral Lanczos’ Tau Method for Systems of Nonlinear Integro-Differential Equations. In Integral Methods in Science and Engineering, Volume 1: Theoretical Techniques; Constanda, C., Dalla Riva, M., Lamberti, P.D., Musolino, P., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 305–314. [Google Scholar]

- Chihara, T.S. An Introduction to Orthogonal Polynomials; Dover Publications: Mineola, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Funaro, D.; Heinrichs, W. Some Results About the Pseudospectral Approximation of One-Dimensional Fourth-Order Problems. Numer. Math. 1990, 58, 399–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanch, G. Mathieu Functions. In Handbook of Mathematical Functions; Abramowitz, M., Stegun, I.A., Eds.; Dover Publications: Mineola, NY, USA, 1974; pp. 721–750. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).