A Geography of the Screen: Mapmaking as Bridge between Film and Curatorial Production Processes

Abstract

:1. Research Intent

2. Introduction

- The territory of a map can be understood as the relationship between a defined geographical area and its representation. In filmmaking, the concept allows us to consider the relationships that exist between the filmmaker(s), the subject(s), and place(s).

- The legend of a map is its key. In filmmaking, the legend can be understood as a set of codes that navigate the spectator into and through the work.

- The modality of a map determines how its data is visualised. In filmmaking, it considers how diverse film production technologies and processes mediate how the territory of a map is aestheticised and the resulting effect on our understanding of its subject.

3. Rhea Storr and Phanuel Antwi

4. Compose the Territory

4.1. Framing the Territory

“Far away is close at hand in images of elsewhere”—Graffiti, author unknown, Paddington Station, London, 1970s

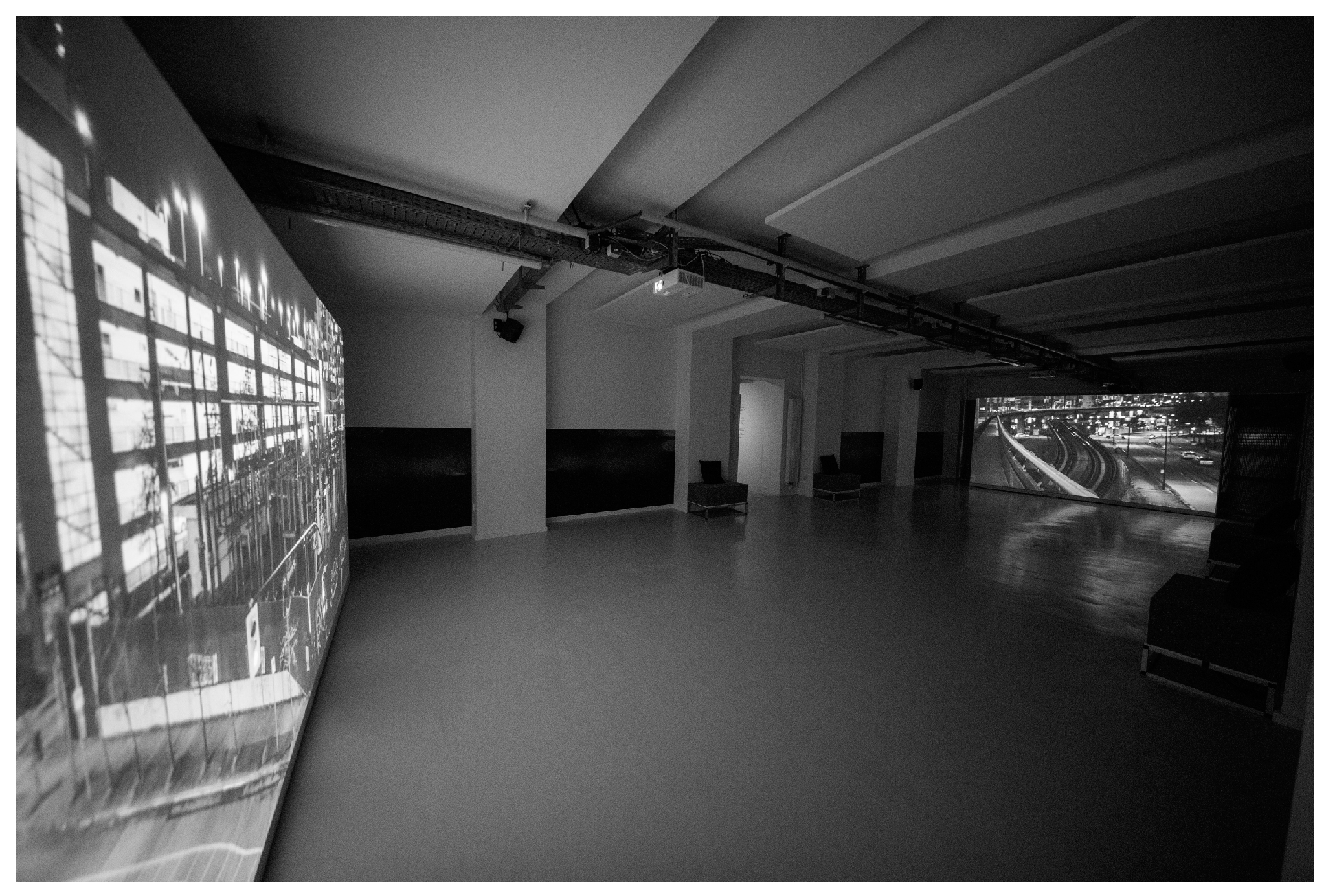

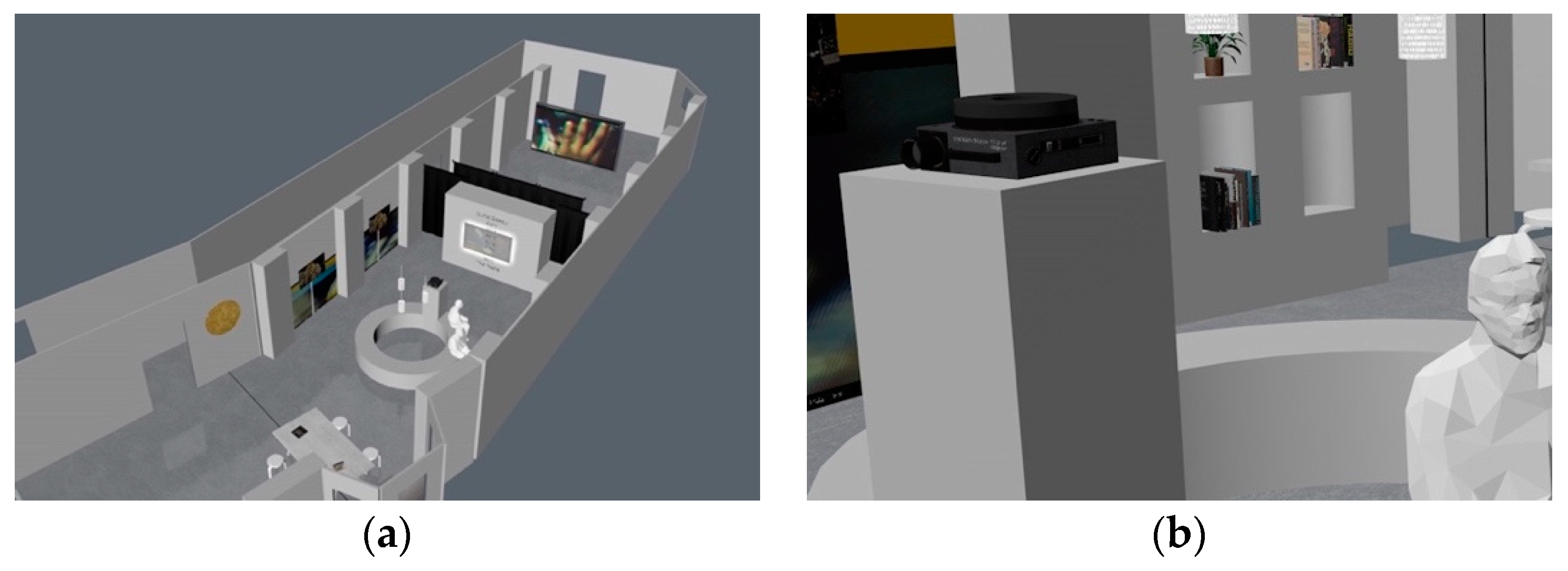

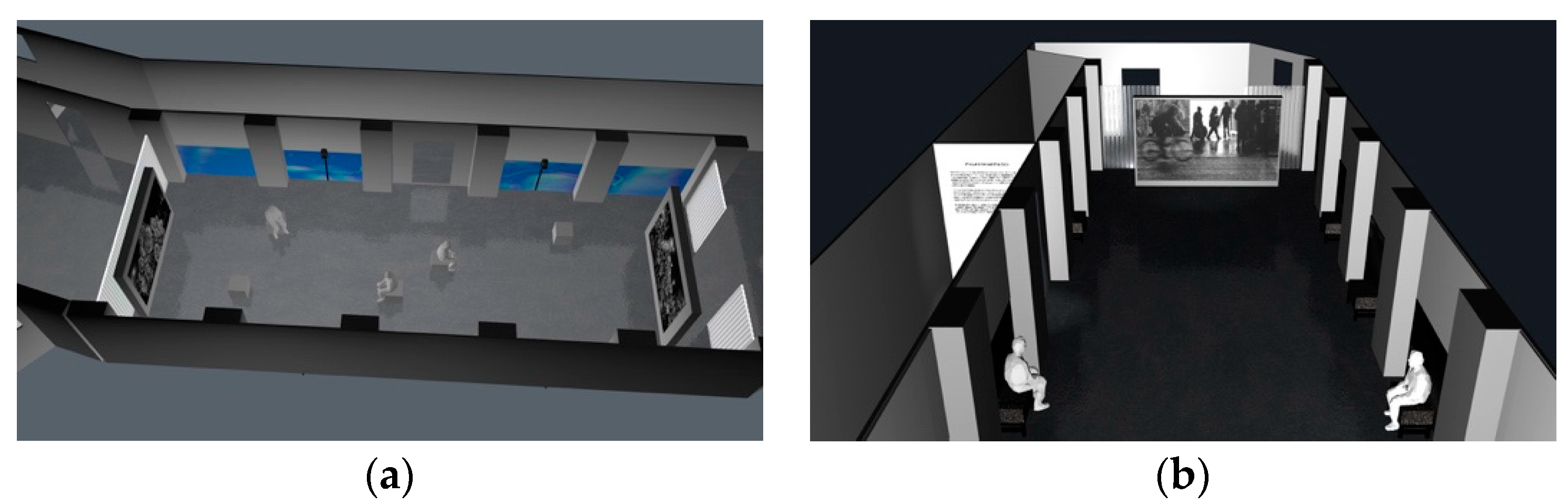

4.2. Framing the Territory: For the Record Design Analysis Part 1

4.3. (Re)Framing the Territory: The Role of Image-Making Technologies in Forming the Territory

4.4. (Re)Framing the Territory: For the Record Design Analysis Part 2

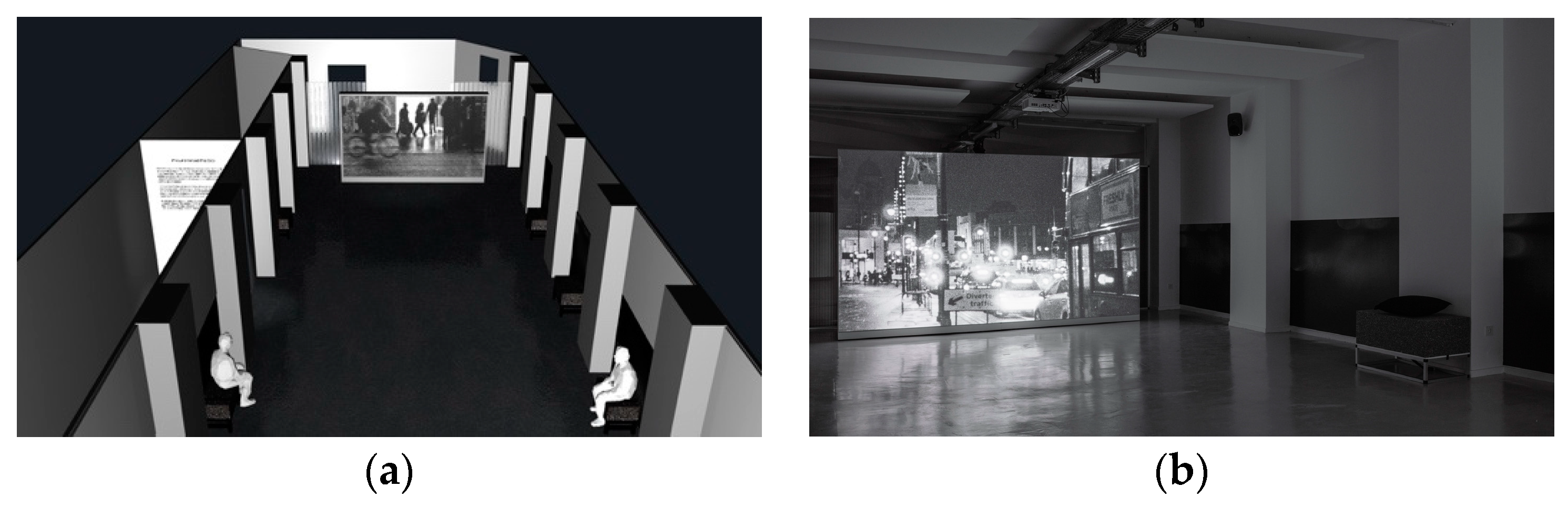

4.5. (Re)Locating the Territory

4.6. (Re)Locating the Territory: For the Record Design Analysis Part 3

5. Defining the Legend

5.1. Opacity

5.2. Design

5.3. Summary

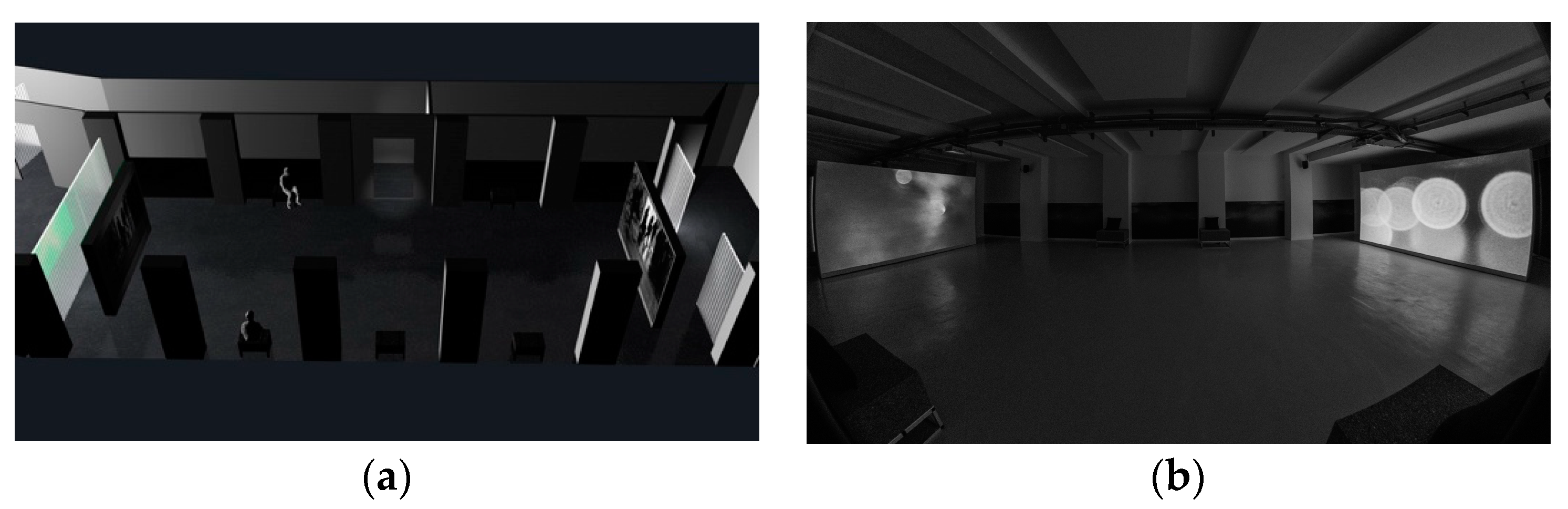

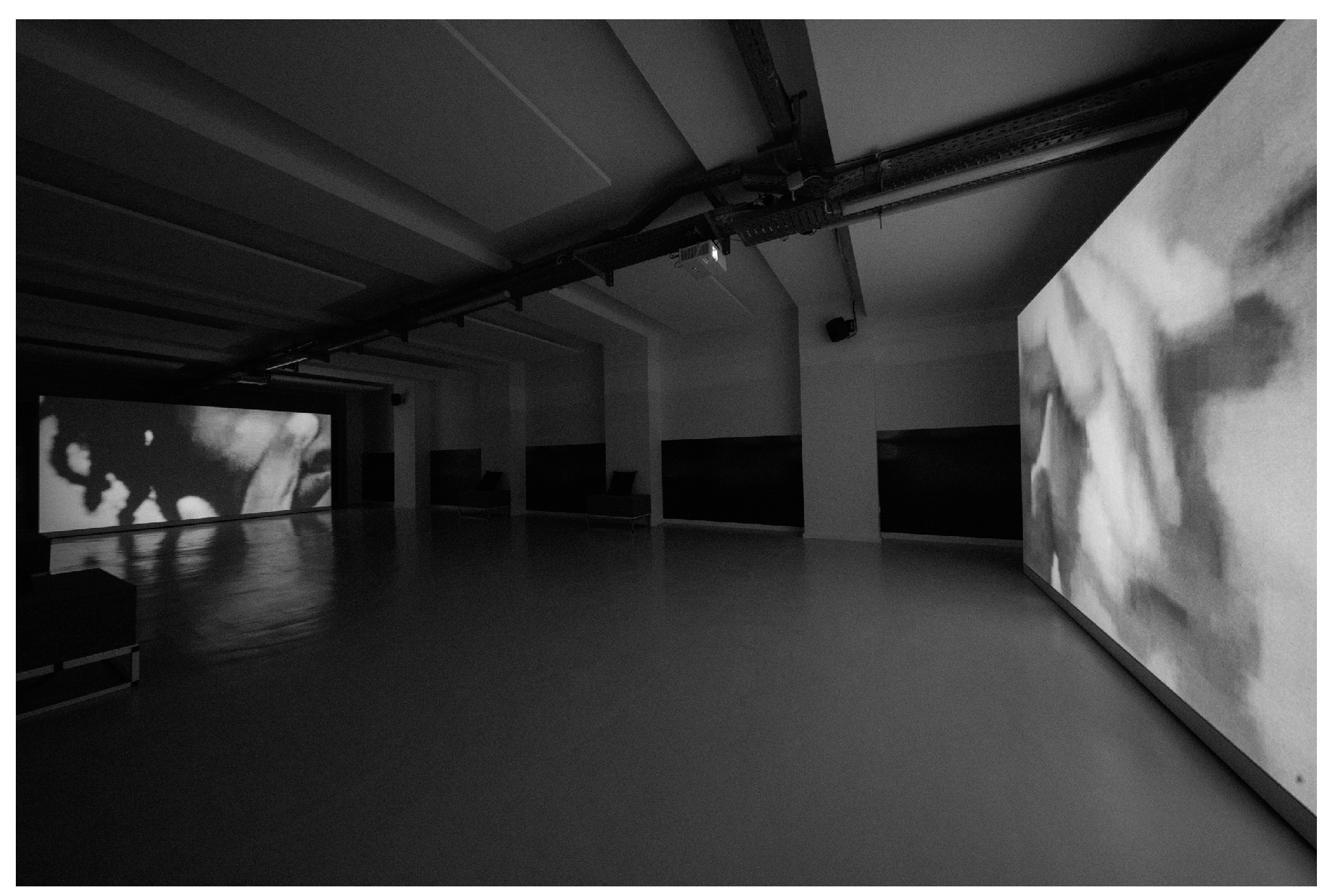

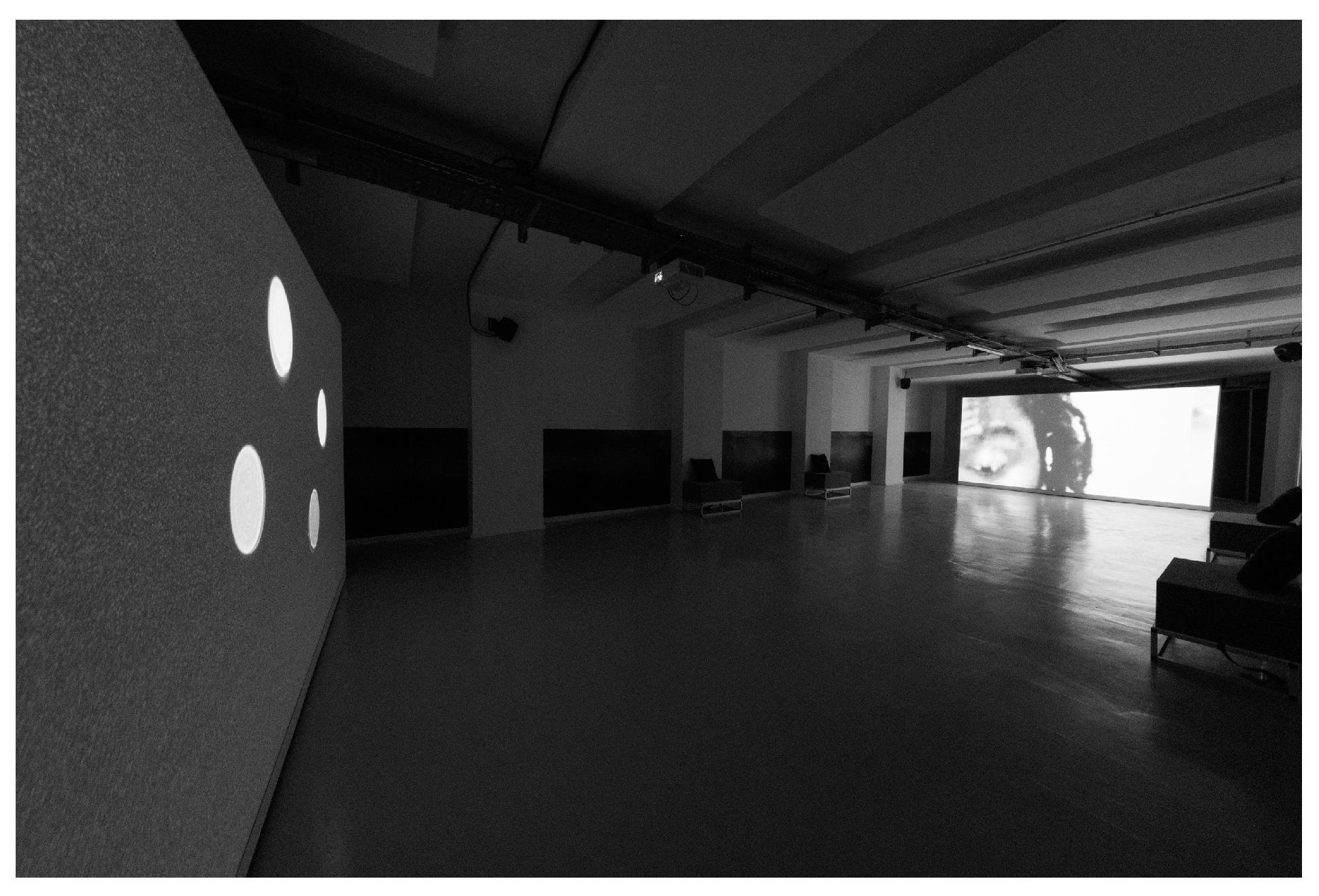

6. Set the Modality

6.1. Defining the Modality

6.2. Deploying the Modality

6.2.1. The Zoom Image

6.2.2. The Zoom Sound

- Our bodies are constantly archiving. Our hearts, (Storr)

- Our hearts, (Antwi)

- Our guts, Our guts,

- Our feet, Our feet,

- Our skin, Our skin,

- Our tongues, Our tongues,

- Our mouths, Our mouths,

- Our anus, Our anus,

- Our unitary tracts, Our unitary tracts,

- Our bloodstream, Our bloodstream,

- In our bodies everything is constantly archiving.

- Let’s find out what we can about each other based on this thing we carry with us all the time.

6.3. Set the Modality

6.4. Summary

7. Conclusions

- Compose the Territory

- 2.

- Define the Legend

- 3.

- Set the Modality

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Martin Lefebvre describes the relationship between landscape and artist documentary film as one in which landscape determines film form, “in the domain of art, landscape is not so much the result of a work; rather, it is the work itself which is the result of the landscape” (Lefebvre 2007). |

| 2 | This speculative approach is adopted to kindle conversations that foreground Black and Asian voices in subjects where those voices have been historically crowded out in the West, in this case, circling subjects of intimacy, touch, and love. |

| 3 | Referencing here Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s understanding of a “body-in-the-world” in which the presence of our physical body within a space alters our perception of it. As a body-in-the-world, we do not view the world from a detached objective position, but rather we live through our body, which in turn helps shape our experience of space (Jean Nouvel in Cairns 2013). |

| 4 | The dérive can be understood as an embodied practice of ‘drifting’ across an urban environment in an unplanned or unstructured manner. Outlined by Guy Debord in 1956 and later taken up by the Situationist International (1957–72), it is a tool associated with psychogeography. Also defined by Debord, psychogeography explores interpersonal relations with place through affect and the resulting actions of the individual. |

| 5 | Punctum draws the viewer into the image and its themes by sparking their subjectivity, the quality of a photograph that Barthes described as “pricking” or “bruising” him (Barthes 1981). |

| 6 | A reference to the common expression for electrical signal interference as ‘white noise’. |

References

- Antwi, Phanuel. 2020. Email message to author. March 12. [Google Scholar]

- Antwi, Phanuel, and Rhea Storr. 2021. For the Record. Berlin: transmediale studio. [Google Scholar]

- Antwi, Phanuel, Rhea Storr, and Ben Evans James. 2021. Down on Record: Interview with Phanuel Antwi and Rhea Storr. Vancouver, Canada, Conversation conducted October 21. [Google Scholar]

- Appleton, Jay. 1996. The Experience of Landscape. New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Baier, Franz Xaver. 2020. Space Is the Place. Edited by Lukas Feireiss. Cambridge and Leipzig: Spector, pp. 84–98. [Google Scholar]

- Balsom, Erica. 2017. After Uniqueness: A History of Film and Video Art in Circulation. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barad, Karen. 2007. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barthes, Roland. 1981. Camera Lucida. New York: Hill & Wang. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, Walter. 2002. Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings Volume 1: 1913–1926. Edited by Marcus Bullock and Michael W. Jennings. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, Walter. 2008. The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility, and Other Writings on Media. Edited by Michael W. Jennings. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, Walter. 2010. On the Concept of History. Berlin: Suhrkamp Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Böhme, Gernot, and Jean-Paul Thibaud. 2016. The Aesthetics of Atmospheres. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bourriaud, Nicolas. 2009. Relational Aesthetics. Dijon: Les presses du reél. [Google Scholar]

- Brackenbury, Dan. 2022. The Ragpicker’s Topology. London: Royal College of Art. [Google Scholar]

- Bruzzi, Stella. 2006. New Documentary, 2nd ed. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cairns, Graham. 2013. The Architecture of the Screen. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cannell, Nina. 2022. Tectonic Tender. Berlin: Berlinische Gallery. [Google Scholar]

- Corner, James. 2011. The Agency of Mapping: Speculation, Critique and Invention. In The Map Reader: Theories of Mapping Practice and Cartographic Representation. Edited by Martin Dodge, Rob Kitchin and Chris Perkins. New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. 1980. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. London: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenstein, Sergei. 1987. Nonindifferent Nature: Film and the Structure of Things. Edited by Herbert Marshall. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eliasson, Olafur. 2003. The Weather Project. London: Tate Modern. [Google Scholar]

- Fineman, Mia. 2004. Kodak and the Rise of Amateur Photography. In Heilburn Timeline of Art History: Essays. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art. Available online: https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/kodk/hd_kodk.htm (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Galibert-Laîné, Chloé. 2022. Lucerne University of Applied Sciences & Arts, Lucerne, Switzerland. Personal communication.

- Glissant, Édouard. 1990. Poetics of Relation. Michigan: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ingold, Tim. 2000. Making Culture and Weaving the World. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lamas, Salomé. 2016. Parafiction. Milan: Mousse Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, Henri. 1991. The Production of Space. Translated by Donald Nicholson-Smith. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, Martin. 2007. Landscape and Film, 1st ed. New York: Taylor and Francis. Available online: https://www.perlego.com/book/1603840/landscape-and-film-pdf (accessed on 30 June 2022).

- Litvintseva, Sasha, Benny Wagner, and Jussi Parikka. 2022. What a Film Can and Can’t Do. BOMB Magazine. Available online: https://bombmagazine.org/articles/sasha-litvintseva-and-beny-wagner-interviewed/(accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Mason-Deese, Liz. 2020. Countermapping. International Encyclopedia of Human Geography, 2nd ed. Edited by Audrey Kobayashi. Amsterdam: Elsevier, vol. 2, pp. 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. 2019. The Film and the New Psychology. In Philosophers on Film from Bergson to Badiou. Edited by Christopher Kul-Want. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 97–112. [Google Scholar]

- Merx, Sigrid. 2020. When Fact Is Fiction: Documentary Art in the Post-Truth Era. Edited by Nele Wynants. Amsterdam: Valiz. [Google Scholar]

- Midal, Alexandra. 2019. Fiction Practice: Prototyping the Otherworldly. Edited by Mariana Pestana. Porto: Onomatopee. [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan, Simon. 2006. Art Encounters Deleuze and Guattari: Thought Beyond Representation. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Parpa, Erica. 2018. Athens, June 18. Wellington: Atlas and Adam Art Gallery. [Google Scholar]

- Ponech, Trevor. 1999. What Is Non-Fiction Cinema? Colorado: Westview Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rancière, Jacques. 2007. The Emancipated Spectator. Artforum International 45: 271–80. [Google Scholar]

- Rivers, Ben. 2016. Ways of Worldmaking. Milan: Mousse Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Sontag, Susan. 1977. On Photography. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. [Google Scholar]

- Storr, Rhea. 2017. Henry. Film. Available online: https://www.rheastorr.com/film/henry (accessed on 11 May 2020).

- Storr, Rhea. 2018. A Protest, A Celebration, A Mixed Message. Film. Available online: https://www.rheastorr.com/film/aprotest (accessed on 12 August 2020).

- Storr, Rhea. 2019. Bragging Rights. Film. Available online: https://www.rheastorr.com (accessed on 12 August 2020).

- Storr, Rhea. 2020a. Here Is the Imagination of the Black Radical. Film. Available online: https://www.rheastorr.com/film/hereistheimagination (accessed on 12 August 2020).

- Storr, Rhea. 2020b. Email message to author. March 12. [Google Scholar]

- Wiens, Birgit, ed. 2019. Contemporary Scenography: Practices and Aesthetics in German Theatre, Arts and Design. London: Methuen. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, Patrick. 2008. Liminal Space in Architecture: Threshold and Transition. Master’s thesis, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN, USA. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

James, B.E. A Geography of the Screen: Mapmaking as Bridge between Film and Curatorial Production Processes. Arts 2023, 12, 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12030094

James BE. A Geography of the Screen: Mapmaking as Bridge between Film and Curatorial Production Processes. Arts. 2023; 12(3):94. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12030094

Chicago/Turabian StyleJames, Ben Evans. 2023. "A Geography of the Screen: Mapmaking as Bridge between Film and Curatorial Production Processes" Arts 12, no. 3: 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12030094

APA StyleJames, B. E. (2023). A Geography of the Screen: Mapmaking as Bridge between Film and Curatorial Production Processes. Arts, 12(3), 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12030094