Situational and Dispositional Achievement Goals’ Relationships with Measures of State and Trait Sport Confidence: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

Study Purposes and Hypotheses

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Information Sources, Search Strategy, and Search Protocol

2.3. Data Retrieved

2.4. Study Quality Rating Scale

2.5. Risk of Bias Statistics

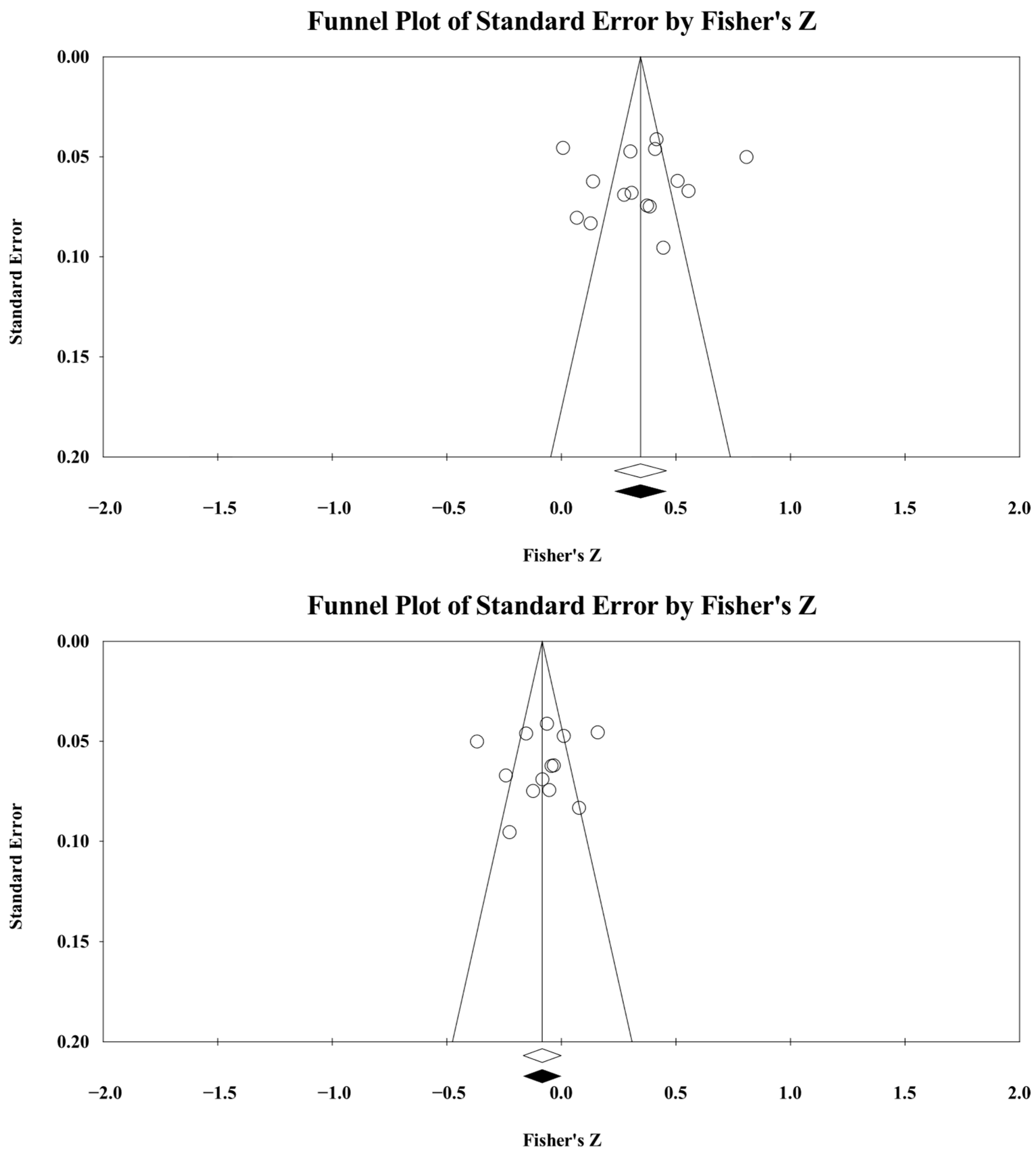

2.6. Summary Statistics and Planned Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.2. Study Quality

3.3. Individual Study Data, Synthesis of Results, and Risk of Bias Across Studies

3.4. Moderator Analyses

3.5. Additional Sensitivity Analyses

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Results

4.2. Limitations and Future Directions

4.3. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Asghar, E., Wang, X., Linde, K., & Alfermann, D. (2013). Comparisons between Asian and German male adolescent athletes on goal orientation, physical self-concept, and competitive anxiety. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 11(3), 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assar, A., Weinberg, R., Ward, R. M., & Vealey, R. S. (2022). The mediating role of self-compassion on the relationship between goal orientation and sport-confidence. Sport Psychologist, 36(4), 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddle, S., Wang, C. K. J., Kavussanu, M., & Spray, C. (2003). Correlates of achievement goal orientations in physical activity: A systematic review of research. European Journal of Sport Science, 3(5), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blank, C., Schobersberger, W., Leichtfried, V., & Duschek, S. (2016). Health psychological constructs as predictors of doping susceptibility in adolescent athletes. Asian Journal of Sports Medicine, 7(4), e35024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borenstein, M. (2019). Common mistakes in meta-analysis and how to avoid them. PDF Provided in CMA Program. Biostat. [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. E., Higgins, J. P. T., & Rothstein, H. R. (2022). Comprehensive meta-analysis software (Version 4). Biostat, Inc.

- Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P., & Rothstein, H. R. (2021). Introduction to meta-analysis. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. (1990). Things I have learned (so far). American Psychologist, 45(12), 1304–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craft, L. L., Magyar, T. M., Becker, B. J., & Feltz, D. L. (2003). The relationship between the Competitive State Anxiety Inventory-2 and sport performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 25(1), 44–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, T., Hill, A. P., Hall, H. K., & Jowett, G. E. (2015). Relationships between the coach-created motivational climate and athlete engagement in youth sport. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 37(2), 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draugelis, S., Martin, J., & Garn, A. (2014). Psychosocial predictors of well-being in collegiate dancers. Sport Psychologist, 28(1), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duda, J. L., & Nicholls, J. G. (1992). Dimensions of achievement motivation in schoolwork and sport. Journal of Educational Psychology, 84(3), 290–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duval, S., & Tweedie, R. (2000). Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot–based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics, 56(2), 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, M. G., Vasconcelos-Raposo, J., & Fernandes, H. M. (2012). Relação entre orientações motivacionais, ansiedade e autoconfiança, e bem-estar subjetivo em atletas brasileiros. Motricidade, 8(3), 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fry, M. D., Hogue, C. M., Iwasaki, S., & Solomon, G. B. (2021). The relationship between the perceived motivational climate in elite collegiate sport and athlete psychological coping skills. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology, 15(4), 334–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayton, W. F., & Nickless, C. J. (1987). An investigation of the validity of the trait and state sport-confidence inventories in predicting marathon performance. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 65(2), 481–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillham, A., Burton, D., & Gillham, E. (2013). Going beyond won-loss record to identify successful coaches: Development and preliminary validation of the Coaching Success Questionnaire-2. International Journal of Sports Science and Coaching, 8(1), 115–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, D., Petlichkoff, L., & Weinberg, R. S. (1984). Antecedents of, temporal changes in, and relationships between CSAI-2 subcomponents. Journal of Sport Psychology, 6(3), 289–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, D., Weiss, M., & Weinberg, R. (1981). Psychological characteristics of successful and nonsuccessful Big Ten wrestlers. Journal of Sport Psychology, 3(1), 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-López, M., Chicau Borrego, C., Marques da Silva, C., Granero-Gallegos, A., & González-Hernández, J. (2020). Effects of motivational climate on fear of failure and anxiety in teen handball players. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(2), 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habeeb, C. M., Barbee, J., & Raedeke, T. D. (2023). Association of parent, coach, and peer motivational climate with high school athlete burnout and engagement: Comparing mediation and moderation models. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 68, 102471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, H. K., & Kerr, A. W. (1997). Motivational antecedents of precompetitive anxiety in youth sport. Sport Psychologist, 11(1), 24–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, H. K., Kerr, A. W., & Matthews, J. (1998). Precompetitive anxiety in sport: The contribution of achievement goals and perfectionism. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 20(2), 194–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harwood, C. G., Keegan, R. J., Smith, J. M. J., & Raine, A. S. (2015). A systematic review of the intrapersonal correlates of motivational climate perceptions in sport and physical activity. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 18, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jekauc, D., Fiedler, J., Wunsch, K., Mülberger, L., Burkart, D., Kilgus, A., & Fritsch, J. (2023). The effect of self-confidence on performance in sports: A meta-analysis and narrative review. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 18(1), 345–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, C., & Nagy, A. (2024). Motivation Profiles, perceived motivational climate, coping perceptions and anxiety among elite young ice hockey players. Physical Culture and Sport. Studies and Research, 105(1), 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kmet, L. M., Cook, L. S., & Lee, R. C. (2004). Standard quality assessment criteria for evaluating primary research papers from a variety of fields. Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research. [Google Scholar]

- Kuan, G., & Roy, J. (2007). Goal profiles, mental toughness and its influence on performance outcomes among wushu athletes. Journal of Sports Science & Medicine, 6(CSSI-2), 28–33. [Google Scholar]

- Kyllo, L. B., & Landers, D. M. (1995). Goal setting in sport and exercise: A research synthesis to resolve the controversy. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 17(2), 117–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lochbaum, M., Cooper, S., & Limp, S. (2022a). The athletic identity measurement scale: A systematic review with meta-analysis from 1993 to 2021. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 12(9), 1391–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lochbaum, M., Kazak Çetinkalp, Z., Graham, K.-A., Wright, T., & Zazo, R. (2016a). Task and ego goal orientations in competitive sport: A quantitative review of the literature from 1989 to 2016. Kinesiology, 48(1), 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lochbaum, M., & Lane, A. M. (2025). Mapping 50 years of sport psychology–performance meta-analyses: A PRISMA-ScR Scoping Review. Sports, 13(12), 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lochbaum, M., Sherburn, M., Sisneros, C., Cooper, S., Lane, A. M., & Terry, P. C. (2022b). Revisiting the self-confidence and sport performance relationship: A systematic review with meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(11), 6381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lochbaum, M., & Sisneros, C. (2024a). A systematic review with a meta-analysis of the motivational climate and hedonic well-being constructs: The importance of the athlete level. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 14(4), 976–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lochbaum, M., & Sisneros, C. (2024b). Situational and dispositional achievement goals and measures of sport performance: A systematic review with a meta-analysis. Sports, 12(11), 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lochbaum, M., Sisneros, C., & Kazak, Z. (2023). The 3 × 2 achievement goals in the education, sport, and occupation literatures: A systematic review with meta-analysis. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 13(7), 1130–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lochbaum, M., Zazo, R., Kazak Çetinkalp, Z., Wright, T., Graham, K.-A., & Konttinen, N. (2016b). A meta-analytic review of achievement goal orientation correlates in competitive sport: A follow-up to Lochbaum et al. (2016). Kinesiology, 48(2), 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonsdale, C., Hodge, K., & Jackson, S. A. (2007). Athlete engagement questionnaire [dataset]. In PsycTESTS dataset. American Psychological Association (APA). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, R., Burton, D., Vealey, R. S., Bump, L., & Smith, D. E. (1983). Competitive state anxiety inventory—2 [dataset]. In PsycTESTS dataset. American Psychological Association (APA). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, P., Rosado, A., Ferreira, V., & Biscaia, R. (2017). Personal and social responsibility among athletes: The role of self-determination, achievement goals and engagement. Journal of Human Kinetics, 57(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, B. D. (1996a). Trait sport confidence, goal orientation and competitive experience of female collegiate volleyball players. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 82(3_suppl), 1085–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, B. D. (1996b). The relationship between middle school aged students goal orientation, self-confidence and competitive sport experience. Journal of Human Movement Studies, 31(1), 39–45. [Google Scholar]

- Morales-Sanchez, V., Caballero-Cerbán, M., Postigo-Martín, C., Morillo-Baro, J. P., Hernández-Mendo, A., & Reigal, R. E. (2022). Perceived motivational climate determines self-confidence and precompetitive anxiety in young soccer players: Analysis by gender. Sustainability, 14(23), 15673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, M., & Duda, J. (1995). Relations of goal orientations and expectations on multidimensional state anxiety. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 81(3_suppl), 1107–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, J. G. (1984). Achievement motivation: Conceptions of ability, subjective experience, task choice, and performance. Psychological Review, 91(3), 328–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntoumanis, N., & Biddle, S. (1998). The relationship between competitive anxiety, achievement goals, and motivational climates. Research Quarterly for Exercise & Sport, 69(2), 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orwin, R. G. (1983). A fail-safe N for effect size in meta-analysis. Journal of Educational Statistics, 8(2), 157–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozer, B., & Kocaeksı, S. (2013). Soccer players efficacy belief, CSAI-2C, SCAT perception and success comparison. Turkish Journal of Sport and Exercise, 15(2), 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., & Moher, D. (2021). Updating guidance for reporting systematic reviews: Development of the PRISMA 2020 statement. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 134, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettersen, S. D., Martinussen, M., Handegård, B. H., Rasmussen, L.-M. P., Koposov, R., & Adolfsen, F. (2023). Beyond physical ability—Predicting women’s football performance from psychological factors. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1146372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineda-Espejel, H. A., Alarcón, E., López-Ruiz, Z., & Trejo, M. (2018). Orientaciones de meta como mediadoras en la relación entre perfeccionismo y ansiedad precompetitiva [Goal orientations as mediators in the relationship between perfectionism and precompetitive anxiety]. RICYDE. Revista Internacional de Ciencias Del Deporte, 14(52), 148–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineda-Espejel, H. A., Alarcón, E., Morquecho-Sánchez, R., Morales-Sánchez, V., & Gadea-Cavazos, E. (2021). Adaptive social factors and precompetitive anxiety in elite sport. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 651169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineda-Espejel, H. A., Alarcón, E., Trejo, M., Chávez, C., & Arce, R. (2016). Personal factors associated with pre-competitive anxiety in elite gymnasts [Dejavniki osebnosti povezani s predtekmovalno napetostjo pri vrhunskih telovadcih in telovadkah]. Science of Gymnastics Journal, 8(3), 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineda-Espejel, H. A., López-Walle, J., & Tomás, I. (2015). Factores situacionales y disposicionales como predictores de la ansiedad y autoconfianza precompetitiva en deportistas universitarios. Cuadernos de Psicología Del Deporte, 15(2), 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reigal-Garrido, R. E., Crespillo-Jurado, M., Morillo-Baro, J. P., & Hernández-Mendo, A. (2018). Autonomy support, perceived motivational climate and psychological sports profile in beach handball players [Apoyo a la autonomía, clima motivacional percibido y perfil psicológico deportivo en jugadores de balonmano playa]. Cuadernos de Psicología del Deporte, 18(3), 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, G. C. (1992). Motivation in sport and exercise: Conceptual constraints and convergence (G. C. Roberts, Ed.). Human Kinetics. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, A. D., Lázaro, J. P., Fernandes, H. M., & Vasconcelos-Raposo, J. (2009). Caracterização dos níveis de negativismo, activação, autoconfiança e orientações motivacionais de alpinistas. Motricidade, 5(2), 63–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, R. (1979). The file drawer problem and tolerance for null results. Psychological Bulletin, 86(3), 638–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancho, A. Z., & Ruiz-Juan, F. (2014). Factores determinantes de la ansiedad en atletas veteranos españoles. Universitas Psychologica, 13(3), 1047–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Rosa, F. J., Montero-Carretero, C., Gómez-Landero, L. A., Torregrossa, M., & Cervelló, E. (2022). Positive and negative spontaneous self-talk and performance in gymnastics: The role of contextual, personal and situational factors. PLoS ONE, 17(3), e0265809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarı, İ., & Bizan, İ. (2022). The role of parent-initiated motivational climate in athletes’ engagement and dispositional flow. Kinesiology, 54(1), 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selfriz, J. J., Duda, J. L., & Chi, L. (1992). The relationship of perceived motivational climate to intrinsic motivation and beliefs about success in basketball. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 14(4), 375–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swann, C., Moran, A., & Piggott, D. (2015). Defining elite athletes: Issues in the study of expert performance in sport psychology. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 16, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tastan, Z., Toros, T., & Kesilmis, I. (2020). The evaluation of mental toughness and goal orientation in students licensed in coaching education departments. Ambient Science, 7(Sp1), 380–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vealey, R. S. (1986). Conceptualization of sport-confidence and competitive orientation: Preliminary investigation and instrument development. Journal of Sport Psychology, 8(3), 221–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vealey, R. S., & Campbell, J. L. (1988). Achievement goals of adolescent figure skaters: Impact on self-confidence, anxiety, and performance. Journal of Adolescent Research, 3(2), 227–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voight, M. R., Callaghan, J. L., & Ryska, T. A. (2000). Relationship between goal orientations, self-confidence and multidimensional trait anxiety among Mexican-American female youth athletes. Journal of Sport Behavior, 23(3), 271–288. [Google Scholar]

- Vosloo, J., Ostrow, A., & Watson, J. C. (2009). The relationships between motivational climate, goal orientations, anxiety, and self-confidence among swimmers. Journal of Sport Behavior, 32(3), 376–393. [Google Scholar]

- Woodman, T., & Hardy, L. (2003). The relative impact of cognitive anxiety and self-confidence upon sport performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Sports Sciences, 21(6), 443–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z., Luo, F., Liu, X., Li, J., Zhou, Y., & Luo, J. (2025). Examining the effects of competitive state anxiety and goal orientation on sports performance of college track and field athletes. Frontiers in Psychology, 16, 1607747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarauz-Sancho, A., Ruiz-Juan, F., Flores-Allende, G., & Arufe Giráldez, V. (2016). Variables predictoras de la percepción del éxito: Aspectos diferenciales en corredores de ruta [Predictor variables of the perception of success: Differential aspects in route runners]. Revista Internacional de Medicina y Ciencias de La Actividad Física y Del Deporte, 16(63), 601–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zmora, G., Trowbridge, C. A., & Been, E. (2026). Psychological Performance determinants in wheelchair basketball: The roles of self-efficacy, sport-confidence, and goal orientation. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, 43(1), 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Country | Sample Size | %F | Level | Sport | AGT | Sport Confidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asghar et al. (2013) Study 1 | CN, DE | 522 | 0 | I | Soccer | GO | S |

| Asghar et al. (2013) Study 2 | DE, PK | 271 | 0 | I | Field Hockey | GO | S |

| Assar et al. (2022) | US | 418 | 50.5 | A | Mix | GO | T |

| Blank et al. (2016) | AT | 1265 | 31.3 | A | Mix | GO | T |

| Curran et al. (2015) | UK | 260 | 57.7 | Y | Soccer | MC | T |

| Draugelis et al. (2014) | US | 182 | 86.3 | A | Dance | MC | T |

| Fernandes et al. (2012) | BR | 169 | 17.2 | M | Mix | GO | S |

| Fry et al. (2021) | US | 467 | 62.3 | A | Mix | MC | T |

| Gillham et al. (2013) Study 3 | US | 396 | 57.3 | A | Mix | MC | T |

| Gómez-López et al. (2020) | ES | 479 | 48.0 | A | Handball | MC | S |

| Habeeb et al. (2023) | US | 150 | 43.3 | I | Mix | MC | T |

| Hall and Kerr (1997) | UK | 111 | 32.4 | Y | Fencing | GO | S |

| Hall et al. (1998) | UK | 119 | 62.2 | I | Cross-Country | GO | S |

| Kiss and Nagy (2024) | HU | 293 | 0 | M | Ice-hockey | MC | S, T |

| Kuan and Roy (2007) | MY | 40 | 48.0 | A | Wushu | GO | T |

| Martins et al. (2017) | PT | 472 | 23.7 | M | Mix | GO | T |

| Morales-Sanchez et al. (2022) | ES | 113 | 44.0 | I | Soccer | MC | S, T |

| Newton and Duda (1995) | US | 107 | NR | R | Tennis | GO | S |

| Ntoumanis and Biddle (1998) | UK | 146 | 42.5 | A | Mix Team | GO, MC | S |

| Ozer and Kocaeksı (2013) | TR | 41 | 0 | Y | Soccer | GO | S |

| Pettersen et al. (2023) | NO | 156 | 100 | E | Soccer | MC | T |

| Pineda-Espejel et al. (2015) | MX | 211 | 54.7 | A | Mix Team | MC, GO | S |

| Pineda-Espejel et al. (2016) | Mix | 37 | 48.0 | E | Gymnastics | GO | S |

| Pineda-Espejel et al. (2018) | Mix | 171 | 52.6 | E | Mix | GO | S |

| Pineda-Espejel et al. (2021) | Mix | 217 | 48.4 | E | Mix | MC | S |

| Reigal-Garrido et al. (2018) | ES | 112 | 44.64 | E | Beach Handball | MC | T |

| Rodrigues et al. (2009) | Mix | 45 | 11.1 | M | Mountaineering | GO | S |

| Sancho and Ruiz-Juan (2014) | ES | 401 | 17.7 | A | Track | GO | S |

| Santos-Rosa et al. (2022) | ES | 258 | 100 | I | Gymnastics | MC | S |

| Sarı and Bizan (2022) | TR | 180 | 54 | I | Mix | MC | T |

| Tastan et al. (2020) | TR | 269 | NR | A | Mix | GO | T |

| Vealey and Campbell (1988) | US | 106 | 89.6 | I | Figure Skating | GO | T |

| Voight et al. (2000) | US | 196 | 100 | I | Volleyball | GO | T |

| Vosloo et al. (2009) | US | 151 | 61.6 | I | Swimming | MC, GO | S |

| Wu et al. (2025) | CH | 87 | 44.8 | A | Track | GO | S |

| Zarauz-Sancho et al. (2016) | ES, MX | 1795 | 15.3 | M | Running | GO | S |

| Zmora et al. (2026) | IL | 48 | 20.8 | M | Basketball | GO | T |

| Effect Size Statistics | Heterogeneity | Bias | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| k | ES | 95% CI | 95% PI | Q | τ2 | I2 | FS | Orwin | Trim/Fill | ES [95% CI] | |

| Task climate | 15 | 0.33 | 0.23, 0.43 | −0.13, 0.68 | 192.67 | 0.05 | 92.73 | 2728 | 39 | 0 | No change |

| Ego climate | 13 | −0.08 | −0.16, −0.00 | −0.38, 0.23 | 79.12 | 0.02 | 84.83 | 102 | 0 | 0 | No change |

| Task orientation | 26 | 0.27 | 0.21, 0.32 | −0.01, 0.51 | 137.26 | 0.02 | 81.78 | 3785 | 42 | 0 | No change |

| Ego orientation | 26 | 0.11 | 0.06, 0.17 | −0.15, 0.36 | 138.93 | 0.02 | 82.01 | 721 | 2 | 3L | 0.09 [0.03, 0.14] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the University Association of Education and Psychology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Quick, H.; Lochbaum, M. Situational and Dispositional Achievement Goals’ Relationships with Measures of State and Trait Sport Confidence: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2026, 16, 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe16020018

Quick H, Lochbaum M. Situational and Dispositional Achievement Goals’ Relationships with Measures of State and Trait Sport Confidence: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2026; 16(2):18. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe16020018

Chicago/Turabian StyleQuick, Hannah, and Marc Lochbaum. 2026. "Situational and Dispositional Achievement Goals’ Relationships with Measures of State and Trait Sport Confidence: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 16, no. 2: 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe16020018

APA StyleQuick, H., & Lochbaum, M. (2026). Situational and Dispositional Achievement Goals’ Relationships with Measures of State and Trait Sport Confidence: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 16(2), 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe16020018