1. Introduction

It is well known that one of the main concerns of human beings lies not only in health but also in finding ways to preserve it (

Vasyl, 2018). Individuals, communities and societies around the globe are concerned with mental health, which is determined by multiple socioeconomic (

Doran & Irina, 2020;

Balon et al., 2016), biological and environmental factors (

Lambrette, 2024); mental health and well-being are fundamental for our collective and individual capacity to think, express feelings, interact with others and enjoy life (

Salud, 2022), and in recent years, the focus on prevention and mental health care has changed from treatment and prevention only to improving the positive aspects of mental health (

Duncan et al., 2021;

Schouler-Ocak, 2023).

Since ancient times, human beings have given great importance to their well-being and overall happiness. Efforts to study these concepts go back to Hellenic philosophy; a satisfying life remains a complex matter, such that it has not been completely clarified (

Hanying, 2023).

Psychological well-being or eudaimonia emphasizes self-realization and growth, the quality of connections with others, self-knowledge, life management and progressing at people’s own pace (

Ryff, 2023), that is, personal development, as well as the ability to create meaning in the face of adversity (

Ryff, 2016). This idea (i.e., eudaimonic well-being) includes the concept of a good life at a secondary level and in a personal and subjective manner (

Kiaei & Reio, 2014). it is possible to improve psychological well-being through behavioral interventions (

Schouler-Ocak, 2023). In this sense, it is important to know the development trajectories of psychological well-being dimensions in order to design interventions that promote mental health and thus achieve a better adaptation to the changes that occur during the life cycle, as well as an optimal execution of the strategies according to the stage lived and considering the characteristics of each person (

Mayordomo et al., 2016).

On the other hand, resilience, a relatively new construct associated with the field of psychology, refers to the factors that favor an individual’s ability to overcome adversity in a healthy way (

Babić et al., 2020). Resilience is not invulnerability or impermeability to stress (

Shackleton et al., 2024), nor is it an intervention technique. Resilience is the ability to endure and defeat adversity, with change and personal self-improvement (

Wu, 2023); resilience is the person’s effective coping in the face of adversity, which not only depends on the situation and the subject but also on the environment and their interaction with it (

Shackleton et al., 2024). Thus, the resilient person is prepared to face contingencies and emerge stronger (

Trejos-Herrera et al., 2023). The resilient personality is made up of three elements that make it possible for resilient responses to be provided in the face of adversity: intrapsychic strengths, skills for action and competencies, and buffer responses (

Puig & Rubio, 2013). Many studies have assessed the association between mental health and resilience; there are several investigations in which resilience has been related to psychological well-being, finding a positive correlation between these variables (

Cejudo et al., 2016;

Guil Bozal et al., 2016;

Shackleton et al., 2024). Resilience is therefore a key point in the development of people’s well-being and health, since if resilient factors and resilient capacity are increased, this could help prevent pathologies as well as improve well-being (

Ovejero Bruna et al., 2016;

Shackleton et al., 2024); resilience research has studied it as a process by which resources protect against the negative impact of stressors to produce positive results (

Shackleton et al., 2024).

In addition to the socio-economic, biological and environmental factors that influence mental health, physical activity has been increasingly recognized as a significant contributor to psychological well-being. Research has consistently shown that engaging in regular physical activity can enhance mental health by reducing symptoms of anxiety and depression, improving mood and increasing overall psychological resilience (

Mammen & Faulkner, 2013;

Schuch et al., 2018). Physical activity is associated with the release of endorphins and other neurochemicals that promote a sense of well-being, while also providing opportunities for social interaction and stress relief (

Craft & Perna, 2004). Furthermore, studies have demonstrated that physical activity can improve self-esteem, cognitive function and emotional regulation, all of which are critical components of psychological well-being (

Biddle & Asare, 2011;

Fox, 1999). Given the growing evidence supporting the positive impact of physical activity on mental health, it is essential to consider its role in interventions aimed at enhancing psychological well-being, particularly among university students who may face high levels of academic stress and emotional challenges.

Arrogante et al. (

2015) proposed a structural model in which resilience was a precursor factor in coping, determining the psychological well-being of nursing, concluding that resilience is an inherent characteristic of nursing personnel, that strategies focused on commitment to the stressful situations determine perceived psychological well-being, and that resilience and more adaptive coping strategies constitute two personal resources that determine psychological well-being.

According to

Ravera et al. (

2016), gender plays a key role in creating resilience, as well as in adaptation pathways.

In their research,

Soysa and Wilcomb (

2015) found that female university students reported lower scores on assessments of psychological health in contrast to their male counter-parts; they also reported that self-efficacy and gender are predictors of well-being. Likewise,

Akhter (

2015), in a study of 100 students, reported statistically significant differences by gender in the levels of psychological well-being, which indicates that there is a difference in psychological well-being between men and women.

The following are the studies carried out with students from Ghana, Turkey, Australia, India and Spain on relationships between resilience, psychological well-being and other variables; it is worth mentioning that in the Mexican context, no research was found in this regard.

In a study conducted by

Cole et al. (

2015) with 431 undergraduate university participants in Ghana, the researchers examined ego resilience and mindfulness and found that these factors cushioned the adverse effects of academic stress on the mental health of university students. An investigation carried out in Turkey with 309 university students by

Malkoç and Yalçın (

2015) assessed the association between resilience, social support, coping and psychological well-being; their findings showed that resilience, coping, and social support from family, friends and other important people predict psychological well-being, and they also showed that the link between resilience and psychological well-being was partially mediated by coping skills.

Aldridge et al. (

2016) examined the relationships between the variables of school environment and the feeling of well-being, life satisfaction, ethnic identity, moral identity and resilience among 2122 Australian students; the authors found that the six factors of school environment were related to students’ well-being, indirectly mediated through a sense of ethical and moral identity, resilience, and satisfaction with life, and the teacher support, school connection and affirmative diversity factors had a direct influence.

In India, researchers explored the relationships between optimism, well-being, resilience and perceived stress in 181 university students. The results revealed that optimism has a significant and positive relationship with well-being and resilience; they also found that well-being was positively correlated with resilience and that resilience is also a predictor of well-being (

Panchal et al., 2016).

Ríos-Risquez et al. (

2016) aimed to examine a model of health to determine the extent to which psychological health was explained by resilience and academic burnout in a sample of 113 Spanish university students; the authors found significant relationships between resilience and the three dimensions of academic burnout. The data also showed a significant and negative relationship between resilience and psychological health, measured as the frequency of psychological symptoms. In terms of resilience and academic burnout, nursing students who reported higher resilience also scored higher on their academic effectiveness and, in turn, showed lower scores for emotional burnout and cynicism.

Resilience, psychological well-being and gender (sex) seem to be related, but we consider it important to further the comprehension of these associations. Thus, the purpose of this research was to build a predictive model of psychological well-being based on sex and resilience factors (strength and confidence, family support, social support and structure). To do this, and in the first place, the psychometric properties of the questionnaires used in this study have been assessed in order to guarantee the adequacy of the selected instruments.

Therefore, the goals of this study were, first, to evaluate the psychometric properties of the QEWB (Questionnaire for Eudaimonic Well-Being) designed by

Waterman et al. (

2010) reviewed by

Schutte et al. (

2013) and the Mexican Resilience Scale (RESI-M) by

Palomar Lever and Gómez Valdez (

2010) and, second, to build a predictive model of the perception of psychological well-being in the dimensions sense of purpose and personal expressiveness with purpose based on the variable sex and the resilience factors (strength and confidence, family support, social support and structure).

Tus, our research questions are: What is the most viable and appropriate factor structure for each of the questionnaires used in the study? And What is the model with the most satisfactory structural fit that explains the functional dependency and interrelationships between the variables studied?

Hypotheses

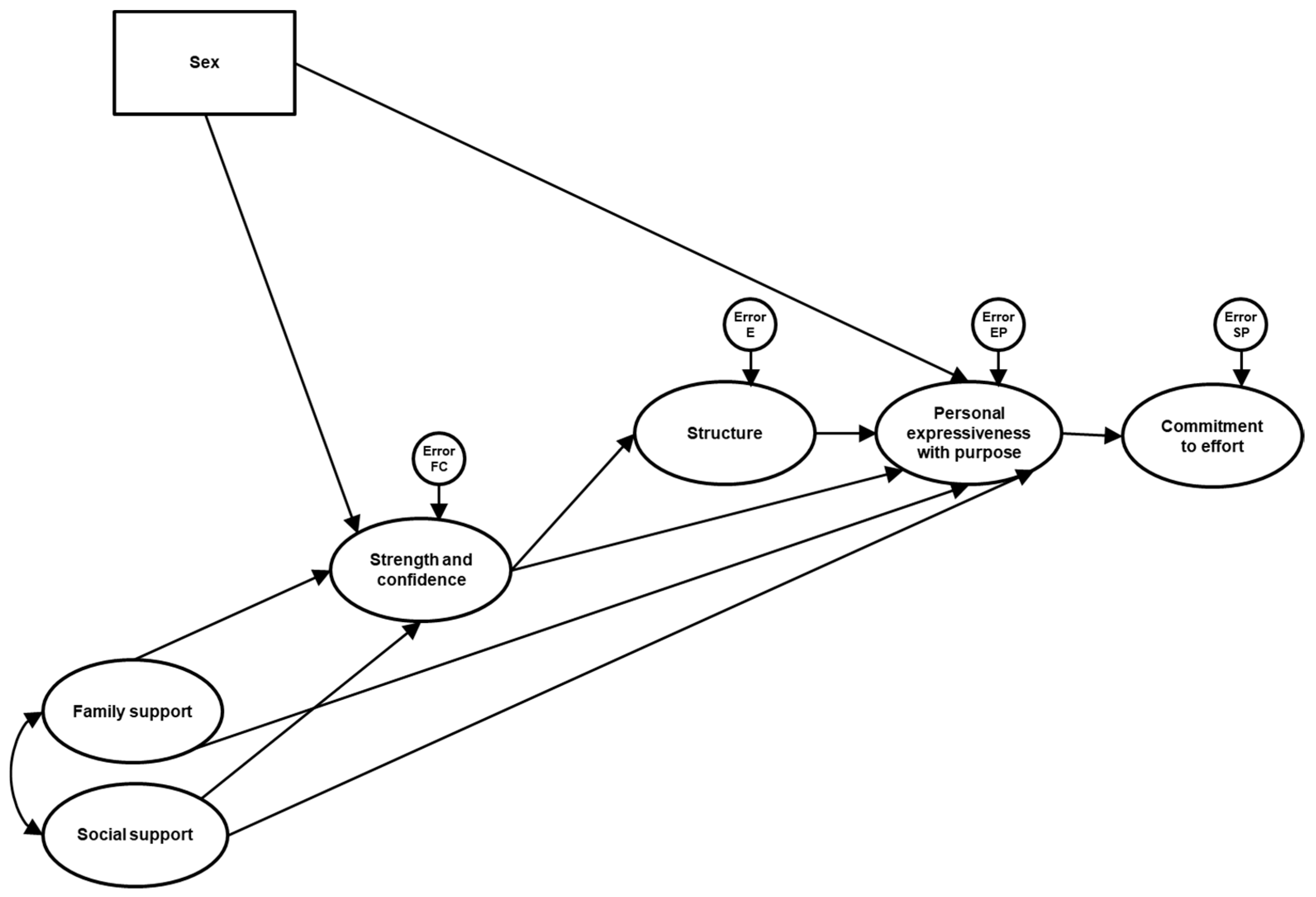

From the initially proposed model that integrates the relationships between perceived psychological well-being, sex, and the factors of strength and trust, family support, social support, and resilience structure (

Figure 1), the following hypotheses emerge:

Effects of Gender on Psychological Well-Being:

H1: The variable of sex has an indirect effect on the perception of psychological well-being mediated by the strength and confidence factor and the resilience structure factor.

H2: The variable of sex has a direct effect on the perception of psychological well-being.

Effects of Resilience Factors on Psychological Well-Being:

H3: The factors of family support, social support, strength and confidence, and structure have a direct effect on the perception of psychological well-being.

H4: The factors of family support and social support indirectly influence psychological well-being through the strength and confidence factor and the structure factor.

H5: The strength and confidence factor indirectly influences psychological well-being through the structure factor.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Of the 1200 invited to participate, only 1190 subjects participated in the study, comprising 628 women (52.77%) and 562 men (47.23%), all university students from Mexico and corresponding to the students who answered all the questionnaires used in this study, and the average age was 20.66 ± 1.89 years.

The research group was selected through convenience sampling, targeting students enrolled in the Human Motricity and Physical Education programs at the Faculty of Physical Culture Sciences. All eligible students were invited to participate, and those who met the inclusion criteria and completed the study protocols were included in the final sample.

The sample was obtained through convenience sampling, trying to cover the representativeness of the different semesters of the degrees offered at the Faculty of Physical Culture Sciences of the 2600 students enrolled.

2.2. Instruments and Variables

QEWB (Questionnaire for Eudaimonic Well-Being) is a psychological well-being questionnaire designed by

Waterman et al. (

2010) and reviewed by

Schutte et al. (

2013). The QEWB consists of 21 Likert-type items that consistently measure well-being based on the philosophy of eudemonia. Seven of the items are stated in the negative sense. It is characterized by three factors: sense of purpose (α = 0.77), personal expressiveness with purpose (α = 0.73), and commitment to effort (α = 0.61).

In the studied model, only the dimensions of a sense of purpose and personal expressiveness with purpose, factors 1 and 2, resulting from the confirmatory factor analyses, were used.

The Mexican Resilience Scale (RESI-M) by

Palomar Lever and Gómez Valdez (

2010) is a Likert-type scale and consists of 43 items grouped into five factors: strength and self-confidence (α = 0.92), social competence (α = 0.87), family support (α = 0.87), social support (α = 0.84) and structure (α = 0.79).

In the studied model, four dimensions of the scale were used: strength and confidence, family support, social support and structure resulting from the confirmatory factor analyses.

For sex the value 0 represents women and 1 represents men.

2.3. Procedure

This research complies with articles 13, 20 and 21 of the Mexican General Health Law on Health Research; in addition, the study was approved by the Scientific Committee of Research and Postgraduate Studies of the Faculty of Physical Sciences Culture at the Autonomous University of Chihuahua. Thus, students enrolled in both undergraduate degree programs offered by the faculty (Human Motricity and Physical Education) were invited to participate. Two self-report instruments were then applied, QEWB and RESI-M, by means of a personal computer (administrator module of the instrument of the typical performance scale editor), in two sessions that lasted approximately 50 min, in the laboratories or computer centers of the FCCF. Before answering the questionnaires, participants were given instructions to access the instrument, while underscoring that the collected data would remain confidential and that their participation was voluntary. That is, they were told that they could withdraw from the study at any time if they so desired; however, the importance of the research was emphasized.

To ensure transparency in the participant selection process, the study applied specific inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria required participants to be undergraduate students enrolled at the Faculty of Physical Culture Sciences, aged between 18 and 28 years, and willing to provide informed consent. Exclusion criteria included students who did not complete all questionnaires or withdrew from the study at any point. These criteria were implemented to maintain the integrity of the sample and ensure the reliability of the results.

Once the instruments were applied, the results of the scale editor version 2.0 were compiled (

Blanco et al., 2013).

For the data analyses, the statistical software SPSS 18.0 and AMOS 21.0 were used.

2.4. Data Analyses

2.4.1. Construct Validity and Reliability of the Instruments

To assess the fit of the factorial structure of the instruments with the studied sample, confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs) were performed using the AMOS 21 program (

Blanco et al., 2013). In each factor, the variances of the error terms were defined as free criteria, while the factor loads were related to one so that the scale was the same as the items. According to

Thompson (

2004), when CFA is employed, researchers must verify not only the model fit, but they should compare the fit of various models in order to select the best one.

For the psychological well-being questionnaire, four measurement models were compared: Model 1 (QEWB-3a), a three-factor model according to the distribution proposed by

Schutte et al. (

2013); for model 2, the items that presented discrimination indices below 0.30 were removed; this model is similar in its factor structure to model 1. Model 3 (QEWB-3c), a three-factor model, was used according to the results of the exploratory factor analysis, and Model 4 (QEWB-3d) was also used, which corresponds to the trifactorial structure of the previous model, eliminating the items that were not sufficiently well explained. And for the resilience scale, two measurement models were compared: Model 1 (RES-IM-5a), a five-factor model according to the original distribution of the items within the questionnaire, and Model 2 (RESIM-5b), which corresponds to a structure of five factors according to the distribution of the model without the items with the lowest saturation in each factor.

2.4.2. Structural Equations Analysis for the Proposed Model

Before using the analysis of structural equations (SEM) to carry out the analysis of the proposed model and to be able to contrast the proposed hypotheses, it was verified that the assumptions underlying this technique were fulfilled, especially those of normality and linearity, for which the values were analyzed for asymmetry and kurtosis and the matrix dispersion graphs of the different variables considered in each model.

Then, from the correlation matrix, SEM was performed using the Maximum Likelihood (ML) estimation method, applying bootstrap resampling procedures for non-normality cases (

Byrne, 2013;

Kline, 2023) in order to test the set of hypothesized explanatory relationships, even though in AMOS 21.0 the ML is especially robust for possible cases of non-normality, especially if the sample is sufficiently large and the asymmetry and kurtosis values are not extreme (asymmetry < |2| and kurtosis < |7|).

The fit of the models was verified using the Chi-square, the goodness of fit index (GFI), the Standardized Residual Mean Square Root (SRMR) and the Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) as absolute measures of fit. The Adjusted Goodness Index (AGFI), the Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI), and the Comparative Goodness-of-Fit Index (CFI) were used as measures of incremental fit. The Chi-square ratio on the degrees of freedom (CMIN/DF) and the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) were used as parsimony fit measures (

Blanco et al., 2013;

Elosua Oliden & Zumbo, 2008). For the GFI, AGFI, TLI, and CFI, values greater than 0.90 and less than 0.08 were established for the RMSEA and SRMR (

Kline, 2023;

Sijtsma, 2009).

Once the best model was obtained, the direct or indirect influence among the variables was examined.

4. Discussion

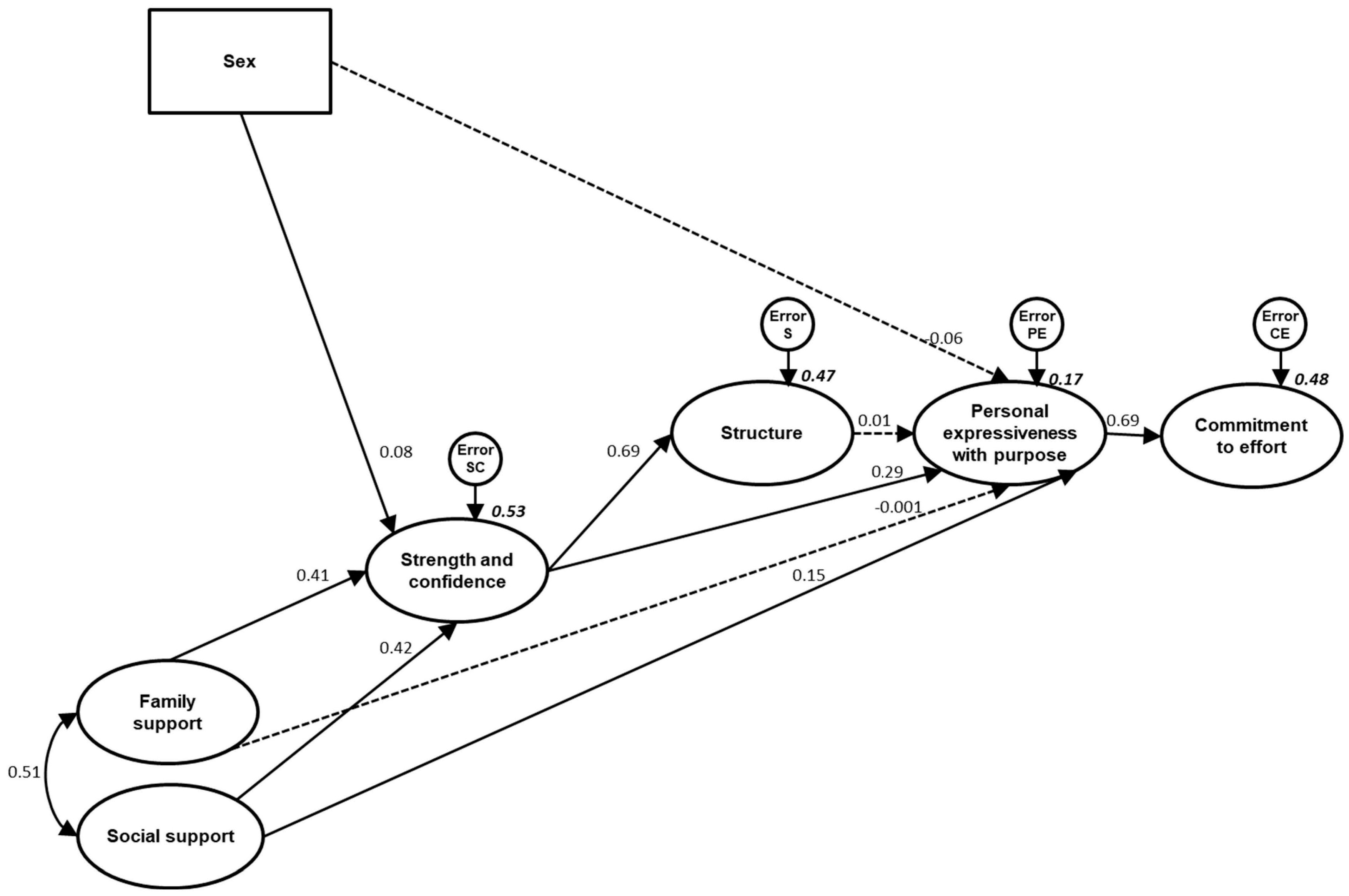

The second goal was to build a predictive model of the perception of psychological well-being in the dimensions of a sense of purpose and personal expressiveness with purpose based on the variable sex and the resilience factors (strength and confidence, family support, social support and structure).

Confirmatory factor analyses performed for the QEWB, the fourth model with three factors, explained 70% of the variance and showed adequate intercorrelations among the factors, providing evidence of an adequate discrimination validity among them. The overall results of the CFA for RESIM of the second model tested, corresponding to a pentafactorial structure, explains 77% of the variance, observing discriminant validity. The participants’ social and cultural differences (for university students in the area of physical activity) could underlie the observed discrepancies between the QEWB of

Schutte et al. (

2013) and the differences found between the model proposed by

Palomar Lever and Gómez Valdez (

2010).

Regarding the prediction of perceived psychological well-being through sex and resilience, most of the hypotheses raised from the initially proposed model have been fulfilled in such a way that both sex and resilience factors positively predict the perception of psychological well-being in the dimension of personal expressiveness with purpose, and this in turn has a positive direct effect on the sense of purpose dimension of psychological well-being; these results are consistent the findings from other research (

Atkinson et al., 2009;

Palomar Lever & Gómez Valdez, 2010;

Ryff, 2023).

In particular, the variable of sex and the family support and social support factors show a positive indirect effect on the perception of psychological well-being through the strength and confidence factor.

The findings of this study are consistent with previous research that has highlighted the importance of resilience and social support in promoting psychological well-being. For example,

Arrogante et al. (

2015) found that resilience and adaptive coping strategies were significant predictors of psychological well-being among nursing professionals, which aligns with our results regarding the mediating role of resilience factors. Similarly,

Soysa and Wilcomb (

2015) reported that self-efficacy and gender were key predictors of well-being, further supporting the indirect effects of sex and resilience observed in our study. Additionally, the positive relationship between family support and psychological well-being echoes findings from

Malkoç and Yalçın (

2015), who demonstrated that social support from family and friends significantly predicted well-being among university students. These comparisons underscore the robustness of our findings and highlight the universal importance of resilience and social support in shaping psychological well-being across different populations.

One of the contributions of this study is the analysis of the interrelationships among all the variables, since no models were found in the literature with the three variables studied; for example, the study by

Arrogante et al. (

2015) found that resilience and more adaptive coping strategies constitute two personal resources that determine psychological well-being, as in the research by

Soysa and Wilcomb (

2015), who reported that self-efficacy and sex are predictors of psychological well-being, results that partially agree with the present study.

Limitations

The present study has some limitations, among them that the participants are all university students, which limits the possibility of generalizing the results; another limitation is that the measurement instruments are self-reported, which may lead to social desirability bias.