Network Analysis of the Association between Minority Stress and Activism in LGB People from Poland

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Minority Stress

1.2. Understanding Activist Engagement

1.3. Role of Activism for Queer Individuals in the Context of Minority Stress

1.4. Aim of This Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Procedure

2.2. Participants

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Demographic Survey

2.3.2. Internalized Homophobia

2.3.3. Expectations of Rejection

2.3.4. Concealment

2.3.5. Sexual Minority Negative Events

2.3.6. Activism

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Differences between Homosexual and Bisexual People in Minority Stress and Activism

3.2. Differences between Activists and Non-Activists in Minority Stress and Activistic Attitude

3.3. Correlations between Minority Stress and Activism

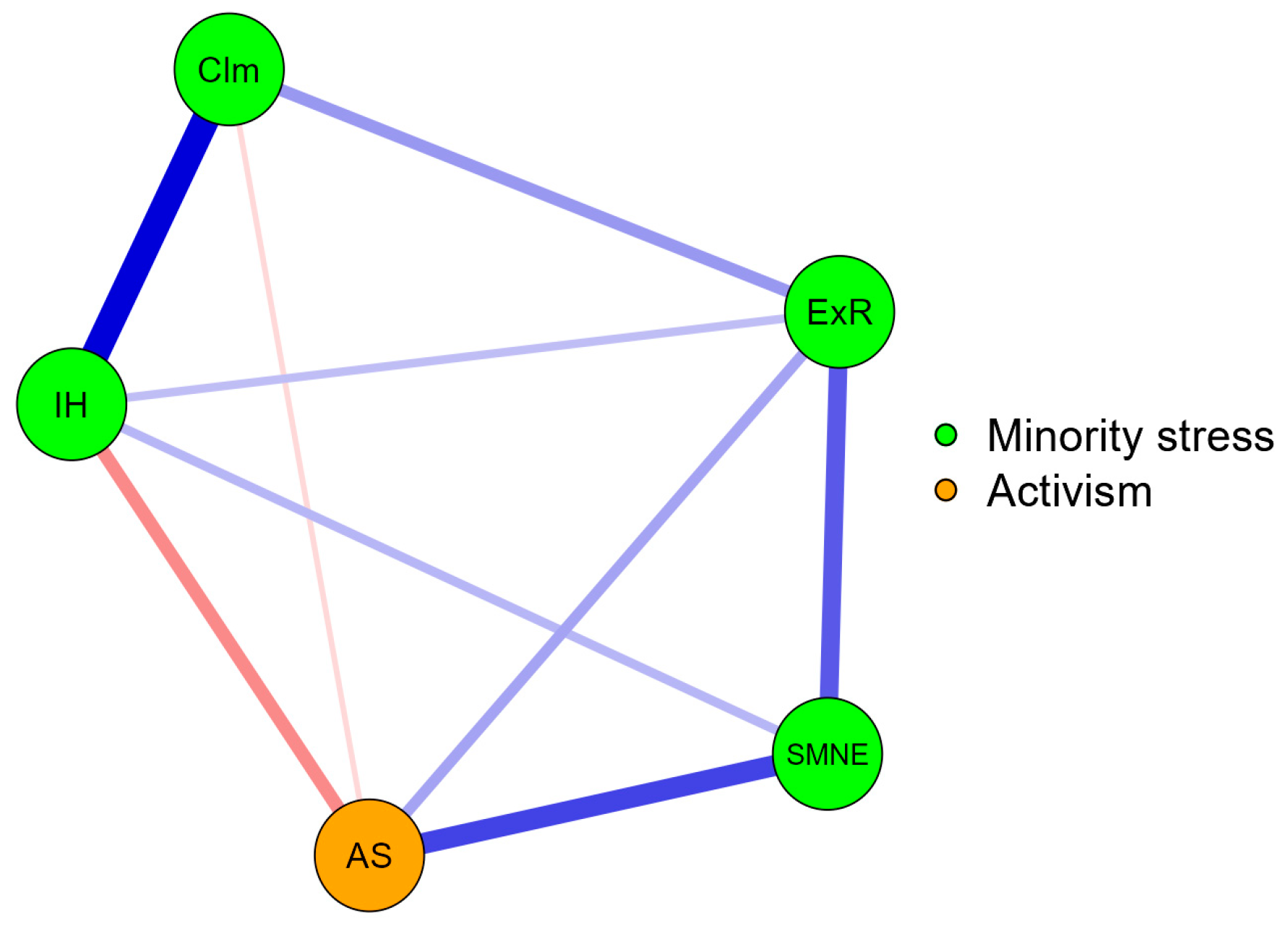

3.4. Network Analysis for Associations between Minority Stress and Activism

4. Discussion

4.1. Intergroup Differences

4.2. Associations between Sexual Minority Stress and Activism

4.3. Limitation of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Meyer, I.H. Prejudice, Social Stress, and Mental Health in Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Populations: Conceptual Issues and Research Evidence. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 5, 674–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rich, A.J.; Salway, T.; Scheim, A.; Poteat, T. Sexual Minority Stress Theory: Remembering and Honoring the Work of Virginia Brooks. LGBT Health 2020, 7, 124–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, H.; Zhou, N.; Fine, M.; Liang, Y.; Li, J.; Mills-Koonce, W.R. Sexual Minority Stress and Same-Sex Relationship Well-Being: A Meta-Analysis of Research Prior to the U.S. Nationwide Legalization of Same-Sex Marriage. J. Marriage Fam. 2017, 79, 1258–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frost, D.M.; Meyer, I.H. Internalized Homophobia and Relationship Quality among Lesbians, Gay Men, and Bisexuals. J. Couns. Psychol. 2009, 56, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoy-Ellis, C.P. Minority Stress and Mental Health: A Review of the Literature. J. Homosex. 2023, 70, 806–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, I.H. Prejudice and Discrimination as Social Stressors. In The Health of Sexual Minorities; M. E. Northridge, W.I.H.M., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 242–267. [Google Scholar]

- Botha, M.; Frost, D.M. Extending the Minority Stress Model to Understand Mental Health Problems Experienced by the Autistic Population. Soc. Ment. Health 2020, 10, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewster, M.E.; Velez, B.L.; Geiger, E.F.; Sawyer, J.S. It’s like Herding Cats: Atheist Minority Stress, Group Involvement, and Psychological Outcomes. J. Couns. Psychol. 2020, 67, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cyrus, K. Multiple Minorities as Multiply Marginalized: Applying the Minority Stress Theory to LGBTQ People of Color. J. Gay Lesbian Ment. Health 2017, 21, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrester, S.N.; Gallo, J.J.; Whitfield, K.E.; Thorpe, R.J., Jr. A Framework of Minority Stress: From Physiological Manifestations to Cognitive Outcomes. Gerontologist 2019, 59, 1017–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, D.; Leblanc, A.; Devries, B.; Alston-Stepnitz, E.; Stephenson, R.; Woodyatt, C. Couple-Level Minority Stress: An Examination of Same-Sex Couples’ Unique Experiences. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2017, 58, 002214651773675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iniewicz, G.; Sałapa, K.; Wrona, M.; Marek, N. Minority Stress among Homosexual and Bisexual Individuals—From Theoretical Concepts to Research Tools: The Sexual Minority Stress Scale. Arch. Psychiatry Psychother. 2017, 3, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neilands, T.; Leblanc, A.; Frost, D.; Bowen, K.; Sullivan, P.; Hoff, C.; Chang, J. Measuring a New Stress Domain: Validation of the Couple-Level Minority Stress Scale. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2020, 49, 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, L.A.; Hastings, P.D. Integrating the Neurobiology of Minority Stress with an Intersectionality Framework for LGBTQ-Latinx Populations. New Dir. Child Adolesc. Dev. 2018, 2018, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witherspoon, R.; Thaeodore, P. Exploring Minority Stress and Resilience in a Polyamorous Sample. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2021, 50, 1367–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, T.L.; Szymanski, D.M. Heterosexist Discrimination and LGBQ Activism: Examining a Moderated Mediation Model. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 2018, 5, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montagno, M.J.; Garrett-Walker, J.J. LGBTQ+ Engagement in Activism: An Examination of Internalized Heterosexism and LGBTQ+ Community Connectedness. J. Homosex. 2022, 69, 911–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szymanski, D.M.; Goates, J.D.; Strauss Swanson, C. LGBQ Activism and Positive Psychological Functioning: The Roles of Meaning, Community Connection, and Coping. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 2021, 10, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiden-Rootes, K.M.; Hartwell, E.E.; Nedela, M.R. Comparing the Partnering, Minority Stress, and Depression for Bisexual, Lesbian, and Gay Adults from Religious Upbringings. J. Homosex. 2020, 68, 2323–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinstein, B.A.; Dyar, C. Bisexuality, Minority Stress, and Health. Curr. Sex. Health Rep. 2017, 9, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klar, M.; Kasser, T. Some Benefits of Being an Activist: Measuring Activism and Its Role in Psychological Well-being. Polit. Psychol. 2009, 30, 755–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasko, K.; Szastok, M.; Grzymala-Moszczynska, J.; Maj, M.; Kruglanski, A.W. Rebel with a Cause: Personal Significance from Political Activism Predicts Willingness to Self-sacrifice. J. Soc. Issues 2019, 75, 314–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasso, M.T.; Yoxon, B.; Karampampas, S.; Temple, L. Relative Deprivation and Inequalities in Social and Political Activism. Acta Polit. 2019, 54, 398–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.J.; Pettigrew, T.F.; Pippin, G.M.; Bialosiewicz, S. Relative Deprivation: A Theoretical and Meta-Analytic Review. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2012, 16, 203–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kteily, N.; Bruneau, E. Backlash: The Politics and Real-World Consequences of Minority Group Dehumanization. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 43, 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piazza, J.A. Poverty, Minority Economic Discrimination, and Domestic Terrorism. J. Peace Res. 2011, 48, 339–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruglanski, A.W.; Gelfand, M.J.; Bélanger, J.J.; Sheveland, A.; Hetiarachchi, M.; Gunaratna, R. The Psychology of Radicalization and Deradicalization: How Significance Quest Impacts Violent Extremism. Polit. Psychol. 2014, 35, 69–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winiewski, M. Doświadczenie przemocy in Sytuacja społeczna osób LGBTA w Polsce. In Raport za Lata 2019–2020; Winiewski, M., Świder, M., Eds.; Kampania Przeciw Homofobii; Stowarzyszenie Lambda Warszawa: Warsaw, Poland, 2021; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Budziszewska, M.; Górska, P.; Knut, P.; Łada, P. Hate No More: Raport o Polsce: Homofobiczne i Transfobiczne Przestępstwa z Nienawiści a Wymiar Sprawiedliwości; Kampania Przeciw Homofobii: Warszawa, Poland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Country Ranking|Rainbow Europe. Available online: https://www.rainbow-europe.org/country-ranking (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Gorski, P.C.; Chen, C. Frayed All over: The Causes and Consequences of Activist Burnout among Social Justice Education Activists. Educ. Stud. 2015, 51, 385–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, D.; Van Beers, R.A. Unintentional Consequences: Facing the Risks of Being a Youth Activist. Educ. 2020, 26, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña, A.M.; Meier, L.; Nah, A.M. Exhaustion, Adversity, and Repression: Emotional Attrition in High-Risk Activism. Perspect. Polit. 2023, 21, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, K.A.; Ramirez, J.L.; Galupo, M.P. Increase in GLBTQ Minority Stress Following the 2016 US Presidential Election. In The 2016 US Presidential Election and the LGBTQ Community; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2020; pp. 132–153. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudoir, S.R.; Wang, K.; Pachankis, J.E. What Reduces Sexual Minority Stress? A Review of the Intervention “Toolkit”. J. Soc. Issues 2017, 73, 586–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, I.H. Resilience in the Study of Minority Stress and Health of Sexual and Gender Minorities. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 2015, 2, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, D.M.; Fine, M.; Torre, M.E.; Cabana, A. Minority Stress, Activism, and Health in the Context of Economic Precarity: Results from a National Participatory Action Survey of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, and Gender Nonconforming Youth. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2019, 63, 511–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Testa, R.J.; Habarth, J.; Peta, J.; Balsam, K.; Bockting, W. Development of the Gender Minority Stress and Resilience Measure. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 2015, 2, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A Flexible Statistical Power Analysis Program for the Social, Behavioral, and Biomedical Sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldblum, P.; Waelde, L.; Skinta, M.; Dilley, J. The Sexual Minority Stress Scale. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Górska, P. LGBT Rights-Related Collective Action by Minority and Majority Group Members. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Górska, P. Efekt “Tęczowej Zarazy”? Postawy Polaków Wobec Osób LGBT w Latach 2018–2019; Center for Research on Prejudice: Warsaw, Poland, 2020; Available online: http://cbu.psychologia.pl/2021/02/20/efekt-teczowej-zarazy-postawy-polakow-wobec-osob-lgbtw-latach-2018-2019/ (accessed on 19 June 2024).

- Meyer, I.H. Minority Stress and Mental Health in Gay Men. In Psychological Perspectives on Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Experiences; Garnets, L.D., Kimmel, D.C., Eds.; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 699–731. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, J.L.; Dean, L. Developing a Community Sample of Gay Men for an Epidemiologic Study of AIDS. Am. Behav. Sci. 1990, 33, 546–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Link, B.G. Understanding Labeling Effects in the Area of Mental Disorders: An Assessment of the Effects of Expectations of Rejection. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1987, 52, 96–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, K.L.; Holmberg, D. Perceived Social Network Support and Well-Being in Same-Sex versus Mixed-Sex Romantic Relationships. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2008, 25, 769–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielding, K.S.; McDonald, R.; Louis, W.R. Theory of Planned Behaviour, Identity and Intentions to Engage in Environmental Activism. J. Environ. Psychol. 2008, 28, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jew, G.; Tran, A.G. Understanding Activist Intentions: An Extension of the Theory of Planned Behavior. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 41, 4885–4897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Categories | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sexual Identification | Bisexual | 94 | 48.96 |

| Lesbian and gay | 98 | 51.04 | |

| Gender Identification | Women | 111 | 57.81 |

| Men | 70 | 36.46 | |

| Nonbinary | 11 | 5.73 | |

| Education | Primary | 12 | 6.25 |

| Vocational | 3 | 1.56 | |

| Secondary | 96 | 50.00 | |

| Higher | 81 | 42.19 | |

| Place of residence | Village | 24 | 12.50 |

| City up to 20,000 inhabitants | 8 | 4.17 | |

| City 20 to 50 thousand inhabitants | 19 | 9.90 | |

| A city of 50,000 to 100,000 inhabitants | 14 | 7.29 | |

| A city of 100,000 to 500,000 inhabitants | 49 | 25.52 | |

| City from 500,000 up to one million inhabitants | 39 | 20.31 | |

| A city with over 1 million inhabitants | 39 | 20.31 |

| Variable | Lesbian & Gay (n = 98) | Bisexual (n = 94) | t (190) | p | d | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | ||||

| Internalized Homophobia | 16.10 | 5.37 | 16.61 | 5.00 | –0.67 | 0.502 | –0.10 |

| Expectation of Rejection | 12.90 | 3.95 | 12.18 | 4.21 | 1.22 | 0.225 | –0.10 |

| Concealment | 11.97 | 4.80 | 11.80 | 4.40 | 0.26 | 0.797 | 0.04 |

| SM Negative Events | 15.67 | 10.29 | 11.63 | 6.97 | 3.18 | 0.002 | 0.46 |

| Activism Scale | 14.91 | 5.81 | 15.30 | 5.24 | –0.49 | 0.626 | –0.07 |

| Variable | Non-Activist (n = 141) | Activist (n = 51) | t (190) | p | d | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | ||||

| Internalized Homophobia | 16.31 | 5.13 | 16.45 | 5.38 | –0.16 | 0.870 | –0.03 |

| Expectation of Rejection | 12.32 | 3.94 | 13.18 | 4.44 | –1.29 | 0.200 | –0.21 |

| Concealment | 11.64 | 4.46 | 12.57 | 4.95 | –1.24 | 0.216 | –0.20 |

| SM Negative Events | 12.24 | 8.47 | 17.71 | 9.38 | –3.84 | <0.001 | –0.63 |

| Activism Scale | 13.76 | 5.49 | 18.80 | 3.64 | –6.10 | <0.001 | –1.00 |

| Scale | Range | M | SD | IH | ExR | Clm | SMNE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. IH | 9–36 | 16.35 | 5.18 | ||||

| 2. ExR | 6–24 | 12.55 | 4.08 | 0.20 ** | |||

| 3. Clm | 6–27 | 11.89 | 4.60 | 0.45 *** | 0.23 ** | ||

| 4. SMNE | 0–47 | 13.69 | 9.03 | 0.13 | 0.35 *** | 0.08 | |

| 5. AS | 3–21 | 15.10 | 5.52 | −0.17 * | 0.21 ** | −0.10 | 0.33 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Krok, A.; Kardasz, Z.; Rogowska, A.M. Network Analysis of the Association between Minority Stress and Activism in LGB People from Poland. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2024, 14, 1853-1867. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe14070122

Krok A, Kardasz Z, Rogowska AM. Network Analysis of the Association between Minority Stress and Activism in LGB People from Poland. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2024; 14(7):1853-1867. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe14070122

Chicago/Turabian StyleKrok, Aleksandra, Zofia Kardasz, and Aleksandra M. Rogowska. 2024. "Network Analysis of the Association between Minority Stress and Activism in LGB People from Poland" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 14, no. 7: 1853-1867. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe14070122

APA StyleKrok, A., Kardasz, Z., & Rogowska, A. M. (2024). Network Analysis of the Association between Minority Stress and Activism in LGB People from Poland. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 14(7), 1853-1867. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe14070122