Examining Students’ Acceptance and Use of ChatGPT in Saudi Arabian Higher Education

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Students’ Acceptance of ChatGPT and Behavioral Intentions

2.2. Students’ Acceptance and Actual Use of ChatGPT

2.3. BI and Use of ChatGPT

2.4. The Role of BI in the Link between Students’ Acceptance and Usage of ChatGPT

3. Methods

3.1. Measures and Scale Development

3.2. Research Sample and Data Collection Method

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results of the Study

5. Discussion and Implications

6. Limitations and Future Research Directions

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hasanein, A.M.; Sobaih, A.E.E. Drivers and Consequences of ChatGPT Use in Higher Education: Key Stakeholder Perspectives. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2023, 13, 2599–2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benuyenah, V. Commentary: ChatGPT use in higher education assessment: Prospects and epistemic threats. J. Res. Innov. Teach. Learn. 2023, 16, 134–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasul, T.; Nair, S.; Kalendra, D.; Robin, M.; Santini, F.d.O.; Ladeira, W.J.; Sun, M.; Day, I.; Rather, R.A.; Heathcote, L. The role of ChatGPT in higher education: Benefits, challenges, and future research directions. J. Appl. Learn. Teach. 2023, 6, 41–56. [Google Scholar]

- Strzelecki, A. To use or not to use ChatGPT in higher education? A study of students’ acceptance and use of technology. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2023, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obaid, O.I.; Ali, A.H.; Yaseen, M.G. Impact of Chat GPT on Scientific Research: Opportunities, Risks, Limitations, and Ethical Issues. Iraqi J. Comput. Sci. Math. 2023, 4, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Watanobe, Y. ChatGPT for education and research: Opportunities, threats, and strategies. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 5783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, M.R. ChatGPT. A conversation on artificial intelligence, chatbots, and plagiarism in higher education. Cell Mol. Bioeng. 2023, 16, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lund, B.D.; Wang, T.; Mannuru, N.R.; Nie, B.; Shimray, S.; Wang, Z. ChatGPT and a new academic reality: Artificial Intelligence-written research papers and the ethics of the large language models in scholarly publishing. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2023, 74, 570–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, M.; Rauschenberger, M.; Schön, E.M. “We Need to Talk About ChatGPT”: The Future of AI and Higher Education. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/ACM 5th International Workshop on Software Engineering Education for the Next Generation (SEENG), Melbourne, Australia, 16 May 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Alotaibi, N.S.; Alshehri, A.H. Prospers and obstacles in using artificial intelligence in Saudi Arabia higher education institutions—The potential of AI-based learning outcomes. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magsamen-Conrad, K.; Upadhyaya, S.; Joa, C.Y.; Dowd, J. Bridging the divide: Using UTAUT to predict multigenerational tablet adoption practices. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 50, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkatesh, V. Adoption and use of AI tools: A research agenda grounded in UTAUT. Ann. Oper. Res. 2022, 308, 641–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahsavar, Y.; Choudhury, A. User Intentions to Use ChatGPT for Self-Diagnosis and Health-Related Purposes: Cross-sectional Survey Study. JMIR Hum. Factors 2023, 10, e47564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menon, D.; Shilpa, K. “Chatting with ChatGPT”: Analyzing the factors influencing users’ intention to Use the Open AI’s ChatGPT using the UTAUT model. Heliyon 2023, 9, e20962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagan, M.; Kilmon, C.; Pandey, V. Exploring the adoption of a virtual reality simulation: The role of perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness and personal innovativeness. Campus-Wide Inf. Syst. 2012, 29, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasilingam, D.L. Understanding the attitude and intention to use smartphone chatbots for shopping. Technol. Soc. 2020, 62, 101280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brachten, F.; Kissmer, T.; Stieglitz, S. The acceptance of chatbots in an enterprise context—A survey study. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 60, 102375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogaji, E.; Balakrishnan, J.; Nwoba, A.C.; Nguyen, N.P. Emerging-market consumers’ interactions with banking chatbots. Telemat. Inform. 2021, 65, 101711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin-Nashwan, S.A.; Sadallah, M.; Bouteraa, M. Use of ChatGPT in academia: Academic integrity hangs in the balance. Technol. Soc. 2023, 75, 102370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Emran, M.; AlQudah, A.A.; Abbasi, G.A.; Al-Sharafi, M.A.; Iranmanesh, M. Determinants of using AI-based chatbots for knowledge sharing: Evidence from PLS-SEM and fuzzy sets (fsQCA). IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2023, 71, 4985–4999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Thong, J.Y.; Xu, X. Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: Extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. MIS Q. 2012, 36, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroughi, B.; Senali, M.G.; Iranmanesh, M.; Khanfar, A.; Ghobakhloo, M.; Annamalai, N.; Naghmeh-Abbaspour, B. Determinants of Intention to Use ChatGPT for Educational Purposes: Findings from PLS-SEM and fsQCA. Int. J. Human–Computer Interact. 2023, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaengchart, Y.; Bhumpenpein, N.; Kongnakorn, K.; Khwannu, P.; Tiwtakul, A.; Detmee, S. Factors influencing the acceptance of ChatGPT usage among higher education students in Bangkok, Thailand. Adv. Knowl. Exec. 2023, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari, C.K.; Bhat, M.A.; Khan, S.T.; Subramaniam, R.; Khan, M.A.I. What drives students toward ChatGPT? An investigation of the factors influencing adoption and usage of ChatGPT. Interact. Technol. Smart Educ. 2023; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar]

- Jo, H. Understanding AI tool engagement: A study of ChatGPT usage and word-of-mouth among university students and office workers. Telemat. Inform. 2023, 85, 102067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Huo, Y. Are users willing to embrace ChatGPT? Exploring the factors on the acceptance of chatbots from the perspective of AIDUA framework. Technol. Soc. 2023, 75, 102362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oye, N.D.; A.Iahad, N.; Ab.Rahim, N. The history of UTAUT model and its impact on ICT acceptance and usage by academicians. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2014, 19, 251–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, S.; Soliman, M. Game of algorithms: ChatGPT implications for the future of tourism education and research. J. Tour. Futur. 2023, 9, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.K.Y.; Zhou, W. Deconstructing Student Perceptions of Generative AI (GenAI) through an Expectancy Value Theory (EVT)-based Instrument. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.01186. [Google Scholar]

- Duong, C.D.; Vu, T.N.; Ngo, T.V.N. Applying a modified technology acceptance model to explain higher education students’ usage of ChatGPT: A serial multiple mediation model with knowledge sharing as a moderator. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2023, 21, 100883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terblanche, N.; Kidd, M. Adoption factors and moderating effects of age and gender that influence the intention to use a non-directive reflective coaching chatbot. SAGE Open 2022, 12, 21582440221096136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anayat, S.; Rasool, G.; Pathania, A. Examining the context-specific reasons and adoption of artificial intelligence-based voice assistants: A behavioural reasoning theory approach. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2023, 47, 1885–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, H.; Wu, Y. An Empirical Study of Adoption of ChatGPT for Bug Fixing among Professional Developers. Innov. Technol. Adv. 2023, 1, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Q.; Lin, Y.; Yu, Z. Factors Influencing Learner Attitudes Towards ChatGPT-Assisted Language Learning in Higher Education. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2023, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Attitudes and normative beliefs as factors influencing behavioral intentions. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1972, 21, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill Series in Psychology; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Matthews, L.M.; Matthews, R.L.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: Updated Guidelines on Which Method to Use. Int. J. Multivar. Data Anal. 2017, 1, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sinkovics, R.R. The Use of Partial Least Squares Path Modeling in International Marketing. In Advances in International Marketing; Sinkovics, R.R., Ghauri, P.N., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2009; Volume 20, pp. 277–319. ISBN 978-1-84855-468-9. [Google Scholar]

- Do Valle, P.O.; Assaker, G. Using Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling in Tourism Research: A Review of Past Research and Recommendations for Future Applications. J. Travel Res. 2016, 55, 695–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Mitchell, R.; Gudergan, S.P. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling in HRM Research. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2020, 31, 1617–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobaih, A.E.E.; Algezawy, M.; Elshaer, I.A. Adopting an Extended Theory of Planned Behaviour to Examine Buying Intention and Behaviour of Nutrition-Labelled Menu for Healthy Food Choices in Quick Service Restaurants: Does the Culture of Consumers Really Matter? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobaih, A.E. Ethical concerns for using artificial intelligence chatbots in research and publication: Evidences from Saudi Arabia. J. Appl. Learn. Teach. 2024, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Profile | Freq. | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 285 | 54.8 |

| Female | 235 | 45.2 | |

| Age | Less than 20 years | 241 | 46.3 |

| 20 to 25 years | 267 | 51.3 | |

| 26 to 30 years | 12 | 2.4 | |

| Study level | Freshman (year one) | 116 | 22.2 |

| Sophomore (year two) | 123 | 23.7 | |

| Junior (year three) | 147 | 28.3 | |

| Senior (year four) | 134 | 25.8 | |

| No | 113 | 21.7 | |

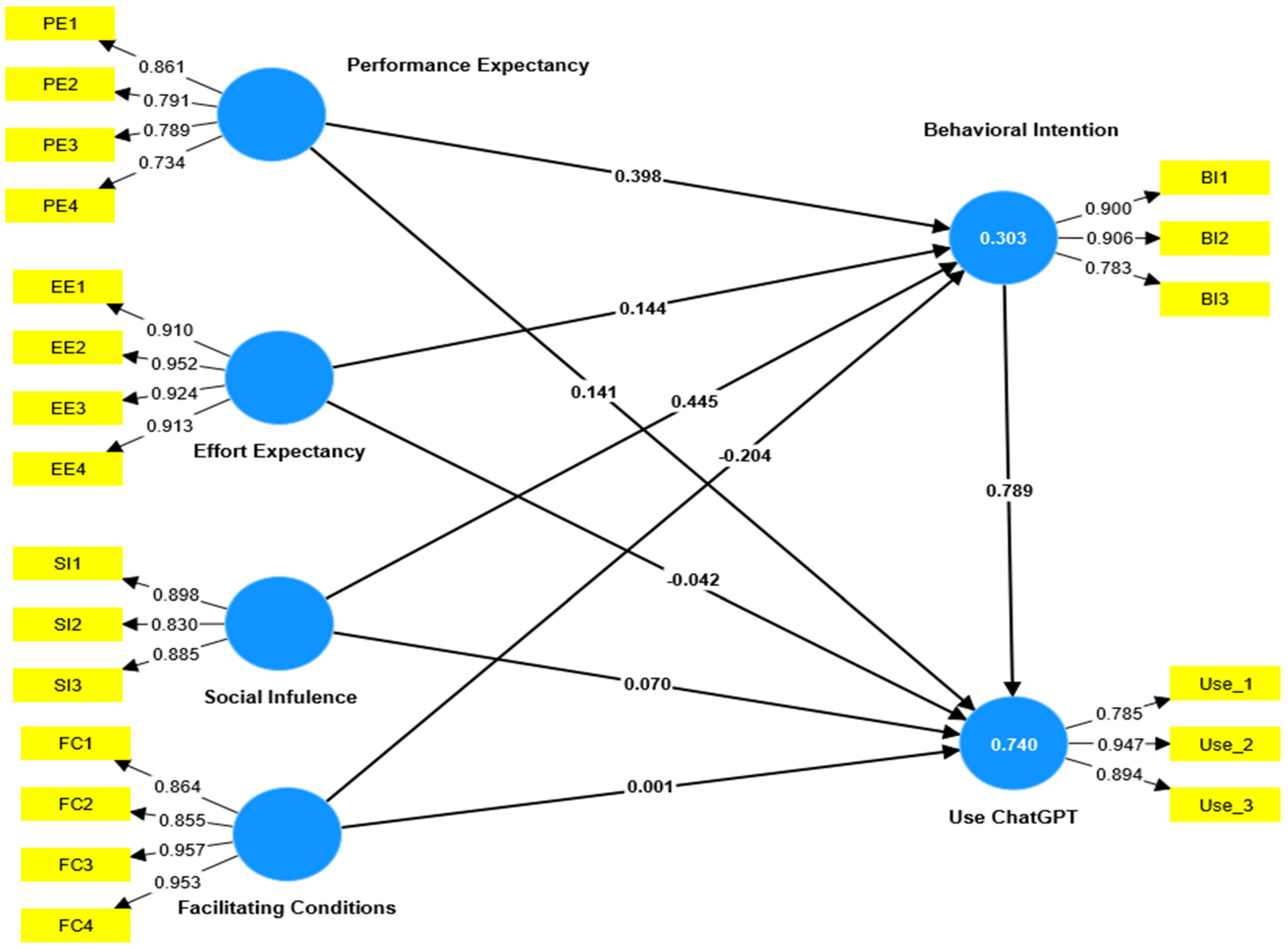

| Scale Variables and Items | Loadings | VIF | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PE: (α = 0.806, CR = 0.815, AVE = 0.632) | |||

| PE1 | “ChatGPT is a valuable tool for my academic pursuits” | 0.861 | 1.613 |

| PE2 | “Utilizing ChatGPT improves the probability of attaining important objectives in your academic pursuits” | 0.791 | 1.710 |

| PE3 | “ChatGPT enhances productivity in academic studies by expediting the completion of tasks and projects” | 0.789 | 1.523 |

| PE4 | “Using ChatGPT can elevate my academic performance” | 0.734 | 1.613 |

| EE: (α = 0.944, CR = 0.959, AVE = 0.855) | |||

| EE1 | “I find it easy to learn how to use ChatGPT” | 0.910 | 4.033 |

| EE2 | “Communication with ChatGPT is transparent and easy to comprehend” | 0.952 | 4.832 |

| EE3 | “ChatGPT is user-friendly and intuitive” | 0.924 | 4.256 |

| EE4 | “I find it effortless to acquire expertise in using ChatGPT” | 0.913 | 3.679 |

| SI: (α = 0.850, CR = 0.904, AVE = 0.760) | |||

| SI1 | “People who play a crucial role in my life are of the opinion that I should utilize ChatGPT” | 0.898 | 1.806 |

| SI2 | “People who shape my behavior recommend the utilization of ChatGPT” | 0.830 | 2.287 |

| SI3 | “Those whose opinions I hold in high esteem suggest that I make use of ChatGPT” | 0.885 | 2.835 |

| FC: (α = 0.939, CR = 0.950, AVE = 0.825) | |||

| FC1 | “I am adequately equipped with the necessary resources to make use of ChatGPT” | 0.864 | 3.984 |

| FC2 | “I am proficient in utilizing ChatGPT due to acquired knowledge” | 0.855 | 4.035 |

| FC3 | “ChatGPT is suitable for the technologies I utilize” | 0.957 | 4.157 |

| FC4 | “When facing difficulties with ChatGPT, it is possible to receive support and aid from external sources” | 0.953 | 3.984 |

| BI: (α = 0.831, CR = 0.855, AVE = 0.747) | |||

| BI1 | “I have decided to continue using ChatGPT in the times ahead” | 0.900 | 2.366 |

| BI2 | “I am dedicated to utilizing ChatGPT as a tool for my studies” | 0.906 | 2.343 |

| BI3 | “I aim to continue using ChatGPT on a frequent basis” | 0.783 | 1.572 |

| Actual Use (AU) (α = 0.848, CR = 0.853, AVE = 0.771) | |||

| AU1 | “I intend to use the knowledge and skills I acquired from the ChatGPT in my educational activities” | 0.785 | 1.578 |

| AU2 | “The knowledge and skills I acquired from the ChatGPT will be useful to me in class” | 0.947 | 4.134 |

| AU3 | “Using ChatGPT has helped to improve my academic performance” | 0.894 | 4.109 |

| BI | EE | FC | PE | SI | Usage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BI | 0.864 | |||||

| EE | 0.058 [0.73] | 0.925 | ||||

| FC | −0.171 [0.154] | 0.450 [0.523] | 0.908 | |||

| PE | 0.297 [0.354] | 0.166 [0.188] | −0.027 [0.066] | 0.795 | ||

| SI | 0.319 [0.361] | −0.136 [0.159] | −0.046 [0.045] | −0.293 [0.354] | 0.872 | |

| Usage | 0.801 [0.195] | 0.017 [0.044] | −0.160 [0.141] | 0.348 [0.417] | 0.286 [0.312] | 0.878 |

| Paths | Path Coefficient | t Statistics | p Values | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PE -> BI [H1]. | 0.398 | 6.346 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| EE -> BI [H2]. | 0.144 | 2.596 | 0.009 | Accepted |

| SI -> BI [H3]. | 0.445 | 7.095 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| FC -> BI [H4]. | −0.204 | 4.635 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| PE -> ChatGPT usage [H5]. | 0.141 | 4.489 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| EE -> ChatGPT usage [H6]. | −0.042 | 1.610 | 0.107 | Rejected |

| SI -> ChatGPT usage [H7]. | 0.070 | 2.603 | 0.009 | Accepted |

| FC -> ChatGPT usage [H8]. | 0.001 | 0.026 | 0.979 | Rejected |

| BI -> ChatGPT usage [H9]. | 0.789 | 27.366 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| Specific indirect paths | ||||

| PE -> BI -> ChatGPT usage [H10]. | 0.314 | 6.076 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| EE -> BI -> ChatGPT usage [H11]. | 0.114 | 2.575 | 0.010 | Accepted |

| SI -> BI -> ChatGPT usage [H12]. | 0.352 | 6.708 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| FC -> BI -> ChatGPT usage [H13]. | −0.161 | 4.540 | 0.000 | Accepted |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sobaih, A.E.E.; Elshaer, I.A.; Hasanein, A.M. Examining Students’ Acceptance and Use of ChatGPT in Saudi Arabian Higher Education. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2024, 14, 709-721. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe14030047

Sobaih AEE, Elshaer IA, Hasanein AM. Examining Students’ Acceptance and Use of ChatGPT in Saudi Arabian Higher Education. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2024; 14(3):709-721. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe14030047

Chicago/Turabian StyleSobaih, Abu Elnasr E., Ibrahim A. Elshaer, and Ahmed M. Hasanein. 2024. "Examining Students’ Acceptance and Use of ChatGPT in Saudi Arabian Higher Education" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 14, no. 3: 709-721. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe14030047

APA StyleSobaih, A. E. E., Elshaer, I. A., & Hasanein, A. M. (2024). Examining Students’ Acceptance and Use of ChatGPT in Saudi Arabian Higher Education. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 14(3), 709-721. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe14030047