Exploring the Impact of Labour Mobility on the Mental Health and Wellbeing of Skilled Trades Workers in Ontario, Canada

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Setting

2.3. Study Participants

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Study Instruments

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics of Study Participants

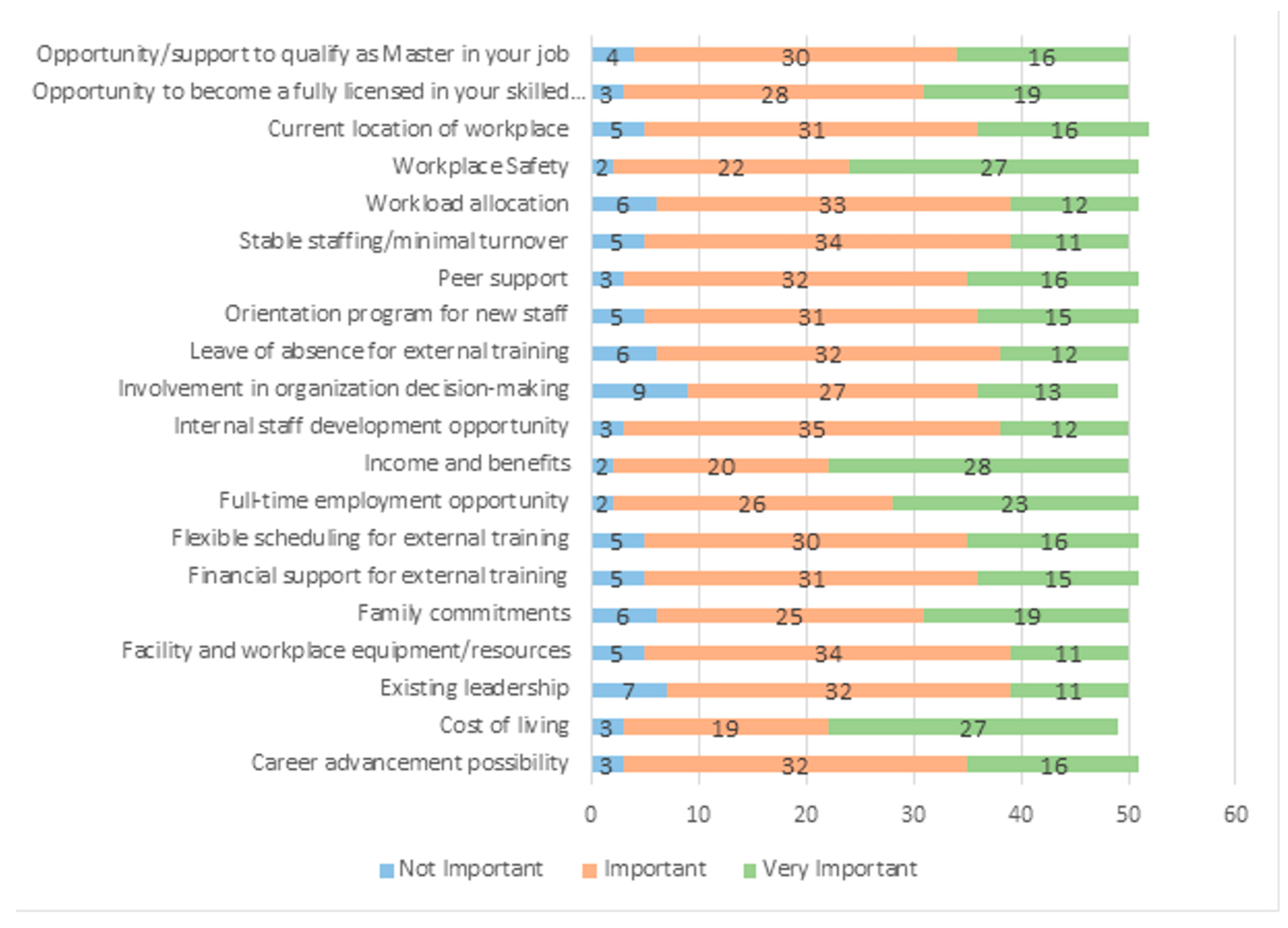

3.2. Importance of Work-Related Factors

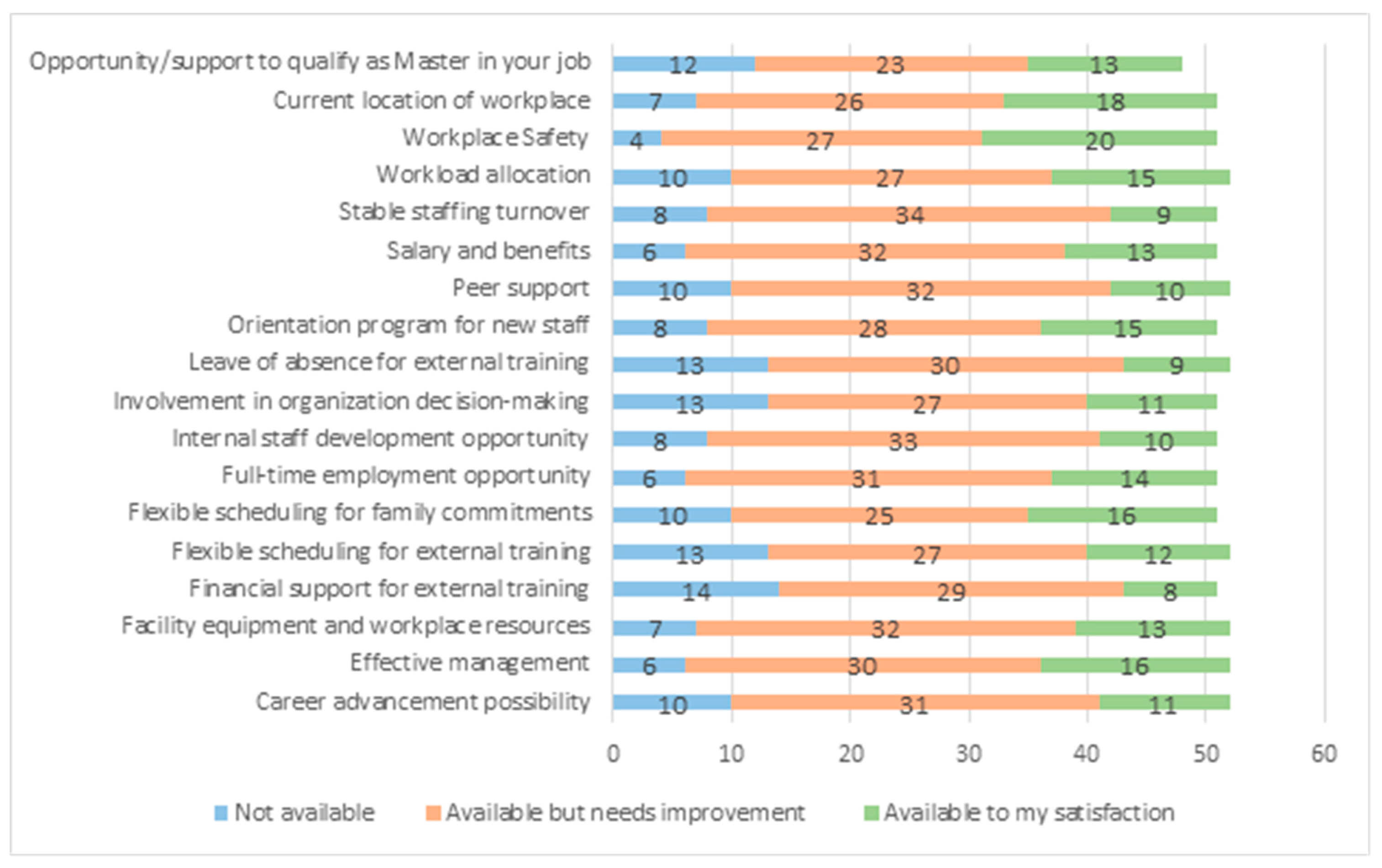

3.3. Availability and Satisfaction with the Work-Related Factors in the Current Workplace

3.4. Burnout

4. Discussion

Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Migration Report 2020. 2020. Available online: https://worldmigrationreport.iom.int/wmr-2020-interactive/ (accessed on 24 May 2023).

- International Labour Office. World Employment Social Outlook; International Labour Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hougaard, C.Ø.; Nygaard, E.; Holm, A.L.; Thielen, K.; Diderichsen, F. Job Mobility and Health in the Danish Workforce. Scand. J. Public Health 2017, 45, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basok, T.; George, G. We Are Part of This Place, but I Do Not Think I Belong. Temporariness, Social Inclusion and Belonging among Migrant Farmworkers in Southwestern Ontario. Int. Migr. 2021, 59, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BlueBranch Inc. Available online: https://bluebranch.ca/ (accessed on 24 May 2023).

- Finnie, R.; Dubois, M.; Miyairi, M. How Much Do They Make? New Evidence on the Early Career Earnings of Trade Certificate Holders. J. Organ. Psychol. 2021, 21, 113–139. [Google Scholar]

- New Registrations in Apprenticeship Programs in Canada Falls in 2019, Led by Sharp Declines in Alberta. 2020. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/201209/dq201209c-eng.htm (accessed on 24 May 2023).

- Morissette, R. Barriers to Labour Mobility in Canada: Survey-Based Evidence; Statistics Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2018.

- Lefebvre, R.; Simonova, E.; Wang, L. Labour Shortages in Skilled Trades- The Best Guestimate? In Issue in Focus; Certified General Accountants Association of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- BuildForce. Construction and Maintenance Looking Forward: An Assessment of Construction Labour Market from 2022 to 2027; Build Force Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Labour Shortage Trends in Canada. 2022. Available online: https://www.statcan.gc.ca/en/subjects-start/labour_/labour-shortage-trends-canada (accessed on 12 February 2023).

- Fair, R.; Sood, S.; Johnston, C.; Tam, S.; Li, B. Analysis on Labour Challenges in Canada, Second Quarter of 2022. Statistics Canada. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-621-m/11-621-m2022011-eng.htm (accessed on 12 February 2023).

- Canivet, C.; Aronsson, G.; Bernhard-Oettel, C.; Leineweber, C.; Moghaddassi, M.; Stengård, J.; Westerlund, H.; Östergren, P.O. The negative effects on mental health of being in a non-desired occupation in an increasingly precarious labour market. SSM-Popul. Health 2017, 3, 516–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristensen, T.S.; Borritz, M.; Villadsen, E.; Christensen, K.B. The Copenhagen Burnout Inventory: A New Tool for the Assessment of Burnout. Work Stress 2005, 19, 192–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. NIOSH Generic Job Stress Questionnaire; CDC and NIOSH: Cincinnati, OH, USA, 2017.

- van Buuren, S.; Groothuis-Oudshoorn, K. Mice: Multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J. Stat. Softw. 2011, 45, 1–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowrouzi, B.; Rukholm, E.; Larivière, M.; Carter, L.; Koren, I.; Mian, O. An Examination of Retention Factors among Registered Practical Nurses in North-Eastern Ontario, Canada. Rural Remote Health 2015, 15, 3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haan, M.; Jin, H.; Paul, T. The Mobility of Construction Workers in Canada: Insights from Administrative Data. Appl. Spat. Anal. Policy 2023, 16, 91–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liljegren, M.; Ekberg, K. Job Mobility as Predictor of Health and Burnout. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2009, 82, 317–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Dai, J.; Wu, N.; Gao, J.; Fu, H. The Mental Health and Depression of Rural-to-Urban Migrant Workers Compared to Non-Migrant Workers in Shanghai: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. Health 2019, 11 (Suppl. S1), S55–S63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Leoncini, R.; Tsai, Y. Intellectual Property Rights Protection, Labour Mobility and Wage Inequality. Econ. Model. 2018, 70, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Cao, J.; Zhang, P.; Wu, G. Investigating the Relationship between Work-To-Family Conflict, Job Burnout, Job Outcomes, and Affective Commitment in the Construction Industry. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lingard, H.; Francis, V. Does a Supportive Work Environment Moderate the Relationship between Work-family Conflict and Burnout among Construction Professionals? Constr. Manag. Econ. 2006, 24, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Wu, Y.; Li, H.; Dan, C. Job Burnout, Work-Family Conflict and Project Performance for Construction Professionals: The Moderating Role of Organizational Support. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, J.; Gou, X.; Li, H.; Xia, N.; Wu, G. Linking Work–Family Conflict and Burnout from the Emotional Resource Perspective for Construction Professionals. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2021, 14, 1093–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouellet-Léveillé, B.; Milan, A. Results from the 2016 Census: Occupations with Older Workers; Statistics Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2019.

- Okereke, G.K.O.; Omeje, H.O.; Nwaodo, S.I.; Chukwu, D.U.; Asogwa, J.O.; Obe, P.I.; Uwakwe, R.C.; Uba, M.B.I.; Edeh, N.C. Reducing Burnout among Building Construction and Mechanical Trade Artisans: The Role of Rational Emotive Behaviour Intervention. J. Ration.-Emot. Cogn.-Behav. Ther. 2022, 40, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.; Fruhen, L.; Burton, C.; McQuade, S.; Loveny, J.; Griffin, M.; Page, A.; Chikritzhs, T.; Crock, S.; Jorritsma, K.; et al. Impact of FIFO Work Arrangements on the Mental Health and Wellbeing of FIFO Workers; Centre for Transformative Work Design: Perth, WA, Australia, 2018; 498p. [Google Scholar]

- Bowers, J.; Lo, J.; Miller, P.; Mawren, D.; Jones, B. Psychological Distress in Remote Mining and Construction Workers in Australia. Med. J. Aust. 2018, 208, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorow, S.; O’Leary, V.; Hilario, C.; Cherry, N.; Daigle, A.; Kelly, G.; Lindquist, K.; Garcia, M.M.; Shmatko, I. Mobile Work and Mental Health a Preliminary Study of Fly-In Fly-Out Workers in the Alberta Oil Sands. 2021. Available online: https://www.cismforcommunities.org/s/Mobile-Work-and-Mental-Health-Report-Dorow-et-al-2021-11-10.pdf (accessed on 14 June 2023).

| Variable | Employees (n = 58) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (Years), Mean (SD) | 32.80 (12.70) | |

| Gender, n (%) | Male | 44 (75.9) |

| Female | 12 (20.7) | |

| Ontario born, n (%) | Yes | 6 (10.3) |

| No | 52 (89.7) | |

| Canada born, n (%) | Yes | 15 (25.9) |

| No | 43 (74.1) | |

| Marital status, n (%) | Single | 38 (65.5) |

| Married | 13 (22.4) | |

| Divorced | 6 (10.3) | |

| Widowed | 1(1.7) | |

| Highest education level, n (%) | Incomplete high school | 10 (17.2) |

| Completed high school | 19 (32.8) | |

| College certificate | 3 (5.2) | |

| College diploma | 6 (10.3) | |

| University graduate degree | 17 (29.3) | |

| University undergraduate degree | 1 (1.7) | |

| Training in Ontario, n (%) | Yes | 18 (31) |

| No | 37 (63.8) | |

| Primary language, n (%) | English | 25 (43.1) |

| Persian | 2 (3.4) | |

| Spanish | 1 (1.7) | |

| Ukrainian | 1 (1.7) | |

| Arabic | 23 (39.7) | |

| Kurdish | 1 (1.7) | |

| Turkish | 1 (1.7) | |

| Dari | 1 (1.7) | |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | White European/North American | 9 (15.5) |

| Middle Eastern | 22 (37.9) | |

| Asian East | 2 (3.4) | |

| Mixed Background | 1 (1.7) | |

| Other | 6 (10.3) | |

| Prefer not to answer | 3 (5.2) | |

| Black African | 3 (5.2) | |

| Asian South | 5 (8.6) | |

| Asian Southeast | 1 (1.7) | |

| Black Caribbean | 3 (5.2) | |

| Aboriginal/Metis/Inuit, n (%) | Yes | 1 (1.7) |

| No | 57 (98.3) | |

| Employment status, n (%) | Full-time, contract | 24 (41.4) |

| Full-time, permanent | 18 (31) | |

| Part-time, contract | 4 (6.9) | |

| Part-time, permanent | 6 (10.3) | |

| Other | 4 (6.9) | |

| Current smoker, n (%) | Yes | 19 (32.8) |

| No | 37 (63.8) | |

| Union, n (%) | Yes | 2 (3.4) |

| No | 53 (91.4) | |

| Stay in the current position for the next 5 years, n (%) | Yes | |

| No | ||

| Type of Burnout | Mean [SD] | Minimum Score | Maximum Score | Median | Moderate Burnout * (n) | High Burnout * (n) | Severe Burnout * (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personal burnout | 46.41 [22.09] | 0.00 | 100 | 45.83 | 15 | 6 | 1 |

| Work-related burnout | 43.21 [19.03] | 14.28 | 100 | 42.85 | 19 | 2 | 1 |

| Colleague-related burnout | 30.36 [22.94] | 0.00 | 100 | 25.00 | 11 | 2 | 1 |

| Type of Burnout | Variable | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Personal Burnout | Age | 0.78 |

| Gender | 0.80 | |

| Level of Education | 0.59 | |

| Born in Canada | 0.20 | |

| Trained in Ontario | 0.85 | |

| Employment Status | 0.79 | |

| Work-related Burnout | Age | 0.26 |

| Gender | 0.36 | |

| Level of Education | 0.83 | |

| Born in Canada | 0.31 | |

| Trained in Ontario | 0.44 | |

| Employment Status | 0.68 | |

| Colleague-Related Burnout | Age | 0.25 |

| Gender | 0.60 | |

| Level of Education | 0.53 | |

| Born in Canada | 0.97 | |

| Trained in Ontario | 0.85 | |

| Employment Status | 0.90 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chattu, V.K.; Bani-Fatemi, A.; Howe, A.; Nowrouzi-Kia, B. Exploring the Impact of Labour Mobility on the Mental Health and Wellbeing of Skilled Trades Workers in Ontario, Canada. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2023, 13, 1441-1451. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe13080105

Chattu VK, Bani-Fatemi A, Howe A, Nowrouzi-Kia B. Exploring the Impact of Labour Mobility on the Mental Health and Wellbeing of Skilled Trades Workers in Ontario, Canada. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2023; 13(8):1441-1451. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe13080105

Chicago/Turabian StyleChattu, Vijay Kumar, Ali Bani-Fatemi, Aaron Howe, and Behdin Nowrouzi-Kia. 2023. "Exploring the Impact of Labour Mobility on the Mental Health and Wellbeing of Skilled Trades Workers in Ontario, Canada" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 13, no. 8: 1441-1451. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe13080105

APA StyleChattu, V. K., Bani-Fatemi, A., Howe, A., & Nowrouzi-Kia, B. (2023). Exploring the Impact of Labour Mobility on the Mental Health and Wellbeing of Skilled Trades Workers in Ontario, Canada. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 13(8), 1441-1451. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe13080105