Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis (HLH): Elusive Diagnosis of Disseminated Mycobacterium avium Complex Infection

Abstract

Introduction

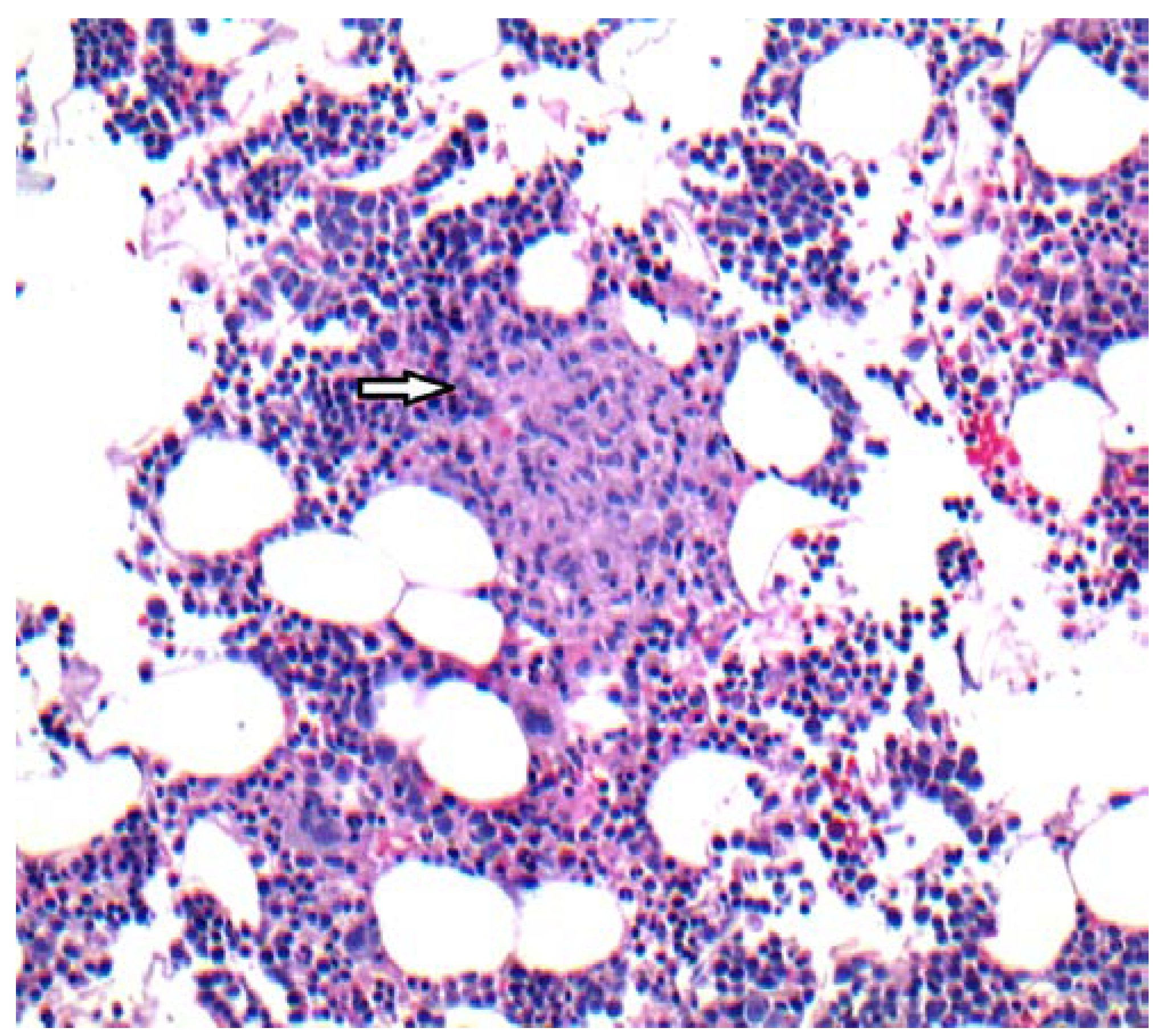

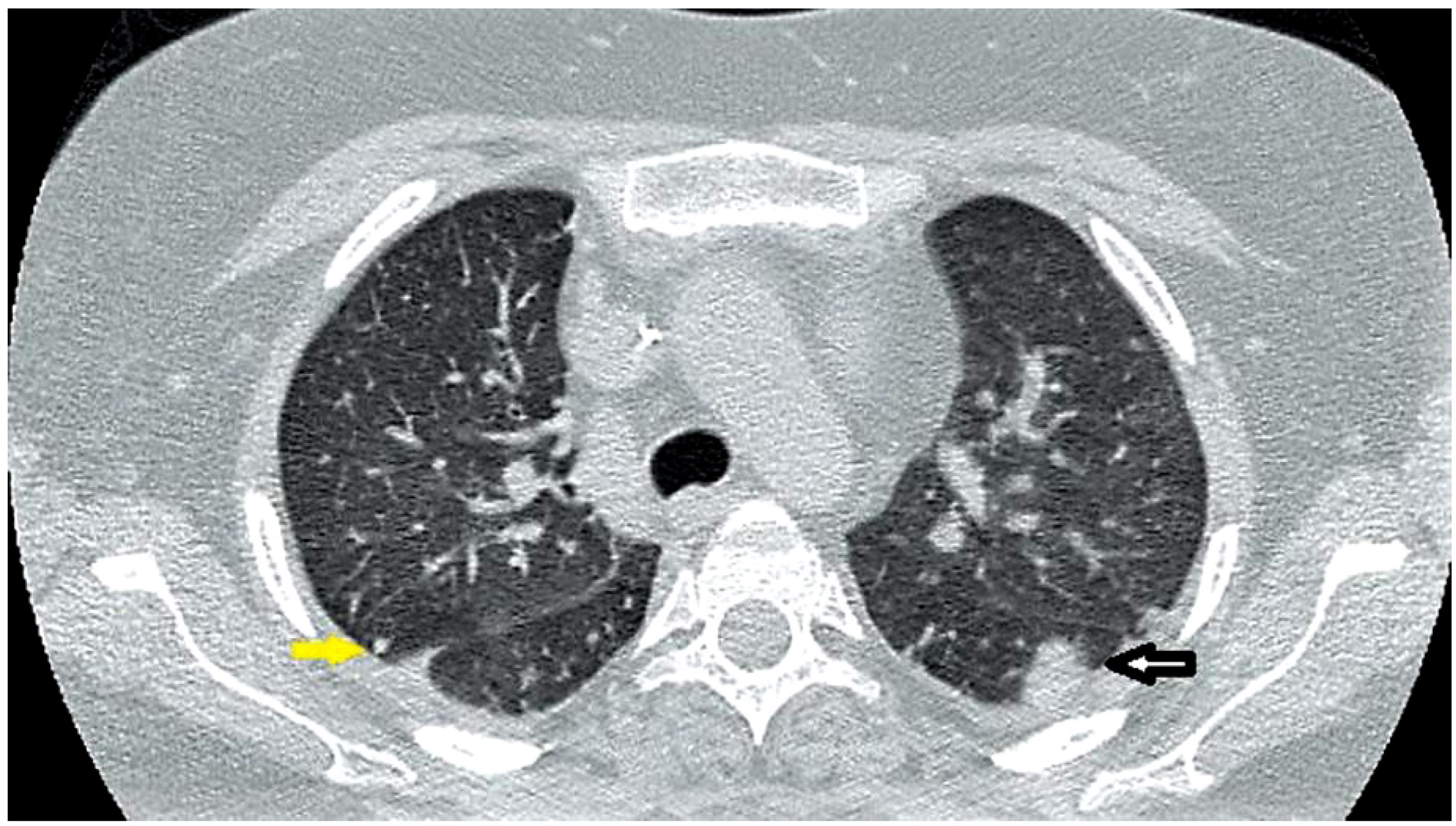

Case report

Discussion

Conclusions

Consent

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Morimoto, A.; Nakazawa, Y.; Ishii, E. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. Pediatr Int 2016, 58, 817–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, H.R.; Ramanan, A.V. Review of haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Arch Dis Child 2011, 96, 688–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henter, J.I.; Horne, A.; Aricó, M.; et al. HLH-2004: Diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2007, 48, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosado, F.G.; Kim, A.S. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: An update on diagnosis and pathogenesis. Am J Clin Pathol 2013, 139, 713–727. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Larroche, C. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults: Diagnosis and treatment. Joint Bone Spine 2012, 79, 356–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, L.; Weitzman, S.S.; Petric, M.; King, S.M. The role of infections in primary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: A case series and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis 2001, 33, 1644–1648. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hui, Y.M.; Pillinger, T.; Luqmani, A.; Cooper, N. Haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis associated with Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. BMJ Case Rep 2015, 2015, pii–bcr2014208220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naha, K.; Dasari, S.; Vivek, G.; Prabhu, M. Disseminated tuberculosis presenting with secondary haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and Poncet’s disease in an immunocompetent individual. BMJ Case Rep 2013, 2013, pii–bcr2012008265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tseng, Y.T.; Sheng, W.H.; Lin, B.H.; et al. Causes, clinical symptoms, and outcomes of infectious diseases associated with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in Taiwanese adults. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 2011, 44, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, Y.H.; Hsu, M.S.; Sheng, W.H.; Chang, S.C. Disseminated Mycobacterium kansasii infection associated with hemophagocytic syndrome. Int J Infect Dis 2010, 14, e262–e264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Chamsi-Pasha, M.A.; Alraies, M.C.; Alraiyes, A.H.; His, E.D. Mycobacterium avium complex-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in a sickle cell patient: An unusual fatal association. Case Rep Hematol 2013, 2013, 291518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koyama, K.; Ohshima, N.; Kawashima, M.; et al. Characteristics of pulmonary Mycobacterium avium complex disease diagnosed later in follow-up after negative mycobacterial study including bronchoscopy. Respir Med 2015, 109, 1347–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benson, C.A.; Williams, P.L.; Currier, J.S.; et al. A prospective, randomized trial examining the efficacy and safety of clarithromycin in combination with ethambutol, rifabutin, or both for the treatment of disseminated Mycobacterium avium complex disease in persons with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Clin Infect Dis 2003, 37, 1234–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© GERMS 2017.

Share and Cite

Ordaya, E.E.; Abu Jarir, S.; Yoo, R.; Chandrasekar, P.H. Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis (HLH): Elusive Diagnosis of Disseminated Mycobacterium avium Complex Infection. Germs 2017, 7, 149-152. https://doi.org/10.18683/germs.2017.1120

Ordaya EE, Abu Jarir S, Yoo R, Chandrasekar PH. Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis (HLH): Elusive Diagnosis of Disseminated Mycobacterium avium Complex Infection. Germs. 2017; 7(3):149-152. https://doi.org/10.18683/germs.2017.1120

Chicago/Turabian StyleOrdaya, Eloy E., Sulieman Abu Jarir, Robert Yoo, and Pranatharthi H. Chandrasekar. 2017. "Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis (HLH): Elusive Diagnosis of Disseminated Mycobacterium avium Complex Infection" Germs 7, no. 3: 149-152. https://doi.org/10.18683/germs.2017.1120

APA StyleOrdaya, E. E., Abu Jarir, S., Yoo, R., & Chandrasekar, P. H. (2017). Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis (HLH): Elusive Diagnosis of Disseminated Mycobacterium avium Complex Infection. Germs, 7(3), 149-152. https://doi.org/10.18683/germs.2017.1120