HLA Class II Alleles in Romanian Patients with Chronic Hepatitis C

Abstract

Introduction

Methods

Results

Discussion

Conclusion

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cooke, G.S.; Lemoine, M.; Thursz, M.; Gore, C.; et al. Viral hepatitis and the Global Burden of Disease: A need to regroup. J Viral Hepat 2013, 20, 600–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Hanafiah, K.; Groeger, J.; Flaxman, A.D.; Wiersma, S.T. Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection: New estimates of age-specific antibody to HCV seroprevalence. Hepatology 2013, 57, 1333–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Hepatitis C Fact sheet N°164 2014. Available online: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs164/en/ (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- World Health Organization. Hepatitis. Data and statistics. 10 May 2015. Available online: http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/communicable-diseases/hepatitis/data-and-statistics (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- The Romanian Association for the Study of the Liver. Guidelines. RASL recommendations for the treatment of HCV infection (in Romanian). 10 May. Available online: http://www.arsf.eu/guidelines.htm (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Esteban, J.I.; Sauleda, S.; Quer, J. The changing epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection in Europe. J Hepatol 2008, 48, 148–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.S.; Tang, Z.H.; Han, J.C.; Xi, M.; Feng, J.; Zang, G.Q. Expression of ICAM-1, HLA-DR, and CD80 on peripheral circulating CD1 alpha DCs induced in vivo by IFN-alpha in patients with chronic hepatitis B. World J Gastroenterol 2006, 12, 1447–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sim, H.; Wojcik, J.; Margulies, M.; Wade, J.A.; Heathcote, J. Response to interferon therapy: Influence of human leucocyte antigen alleles in patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Viral Hepat 1998, 5, 249–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proceedings of the International Workshop on Epidemiology, Diagnosis and Management of Hepatitis C Infection. Medicine and the Community 1996, 6-7, 132.

- Thursz, M.; Yallop, R.; Goldin, R.; Trepo, C.; Thomas, H.C. Influence of MHC class II genotype on outcome of infection with hepatitis C virus. The HENCORE group. Hepatitis C European Network for Cooperative Research. Lancet 1999, 354, 2119–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yee, L.J.; Thursz, M.R. Hepatitis B and C. In Genetic Susceptibility in Infectious Disease; Kaslow, R., McNichol, J., Hill, A.V., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Yee, L.J. Host genetic determinants in hepatitis C virus infection. Genes Immun 2004, 5, 237–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, K.; Norris, S.; Lebeck, L.; et al. HLA class I allelic diversity and progression of fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 2006, 43, 241–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fanning, L.J.; Levis, J.; Kenny-Walsh, E.; Whelton, M.; O’Sullivan, K.; Shanahan, F. HLA class II genes determine the natural variance of hepatitis C viral load. Hepatology 2001, 33, 224–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, X.; Yu, R.B.; Sun, N.X.; Wang, B.; Xu, Y.C.; Wu, G.L. Human leukocyte antigen class II DQB1*0301, DRB1*1101 alleles and spontaneous clearance of hepatitis C virus infection: A meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol 2005, 11, 7302–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- QIAGEN kit handbook or user manual. QIAGEN Group, 2011.

- Invitrogen Life Technologies. AllSet+ Gold SSP and SSP UniTray. 10 May 2015. Available online: http://www.b2b.invitrogen.com/site/us/en/home/Pro ducts-and-Services/Applications/Clinical-andDiagnostic-Applications/Transplant-Diagnostics/TD-Misc/SSP-Typing/Dynal-AllSet-153-SSP.html (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Singh, R.; Kaul, R.; Kaul, A.; Khan, K. A comparative review of HLA associations with hepatitis B and C viral infections across global populations. World J Gastroenterol 2007, 13, 1770–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| DR genotype | Viral load | Liver fibrosis (Metavir score) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DRB1*0701/#13,15 | Viral persistence | high viremia > 10,300,000 IU/mL | F0 = no fibrosis |

| DRB1*0301/#13,14 | Viral persistence | medium viremia 1,680,000–10,300,000 IU/mL | F1 = portal fibrosis without septa (no or minimal fibrosis) |

| DRB1*11/#13.15 DRB1*0101/#13,17 | Decreased disease severity Viral clearance | low viremia < 1,680,000 IU/mL | F2 = portal fibrosis with few septa F3 = numerous septa without cirrhosis (moderate fibrosis) F4 = severe fibrosis |

| Viral loads at onset RT-PCR (IU/mL) | High > 10,300,000 Medium 10,300,000-1,680,000 | 22.3 49.1 |

| Low < 1,680,000 | 29.7 | |

| Extent of liver fibrosis (Metavir score) | Minimal F0/F1 Medium F2/F3 | 12.1 56.5 |

| Severe F4 | 31.4 | |

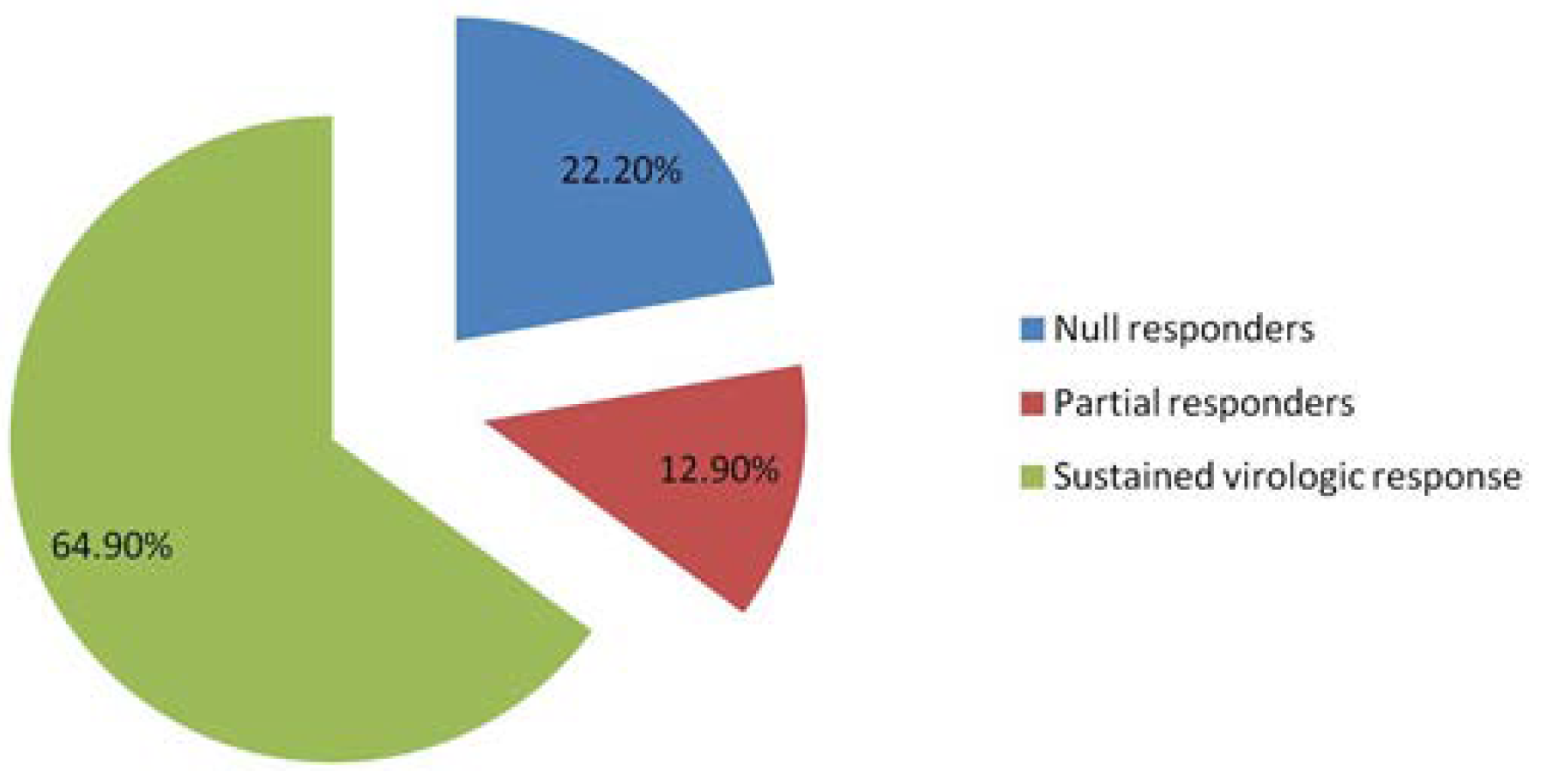

| Therapeutic response 12-20-36 weeks | Null responders after 12 weeks of treatment Partial responders after 20 weeks of treatment | 31.7 18.6 |

| Sustained virologic response after 36 weeks of treatment | 50.1 | |

| Age Years | 28-45 (n=12) >45 (%) (n=42) | 22.2 77.7 |

| Gender | Male (n=23) Female (n=31) | 42.5 57.4 |

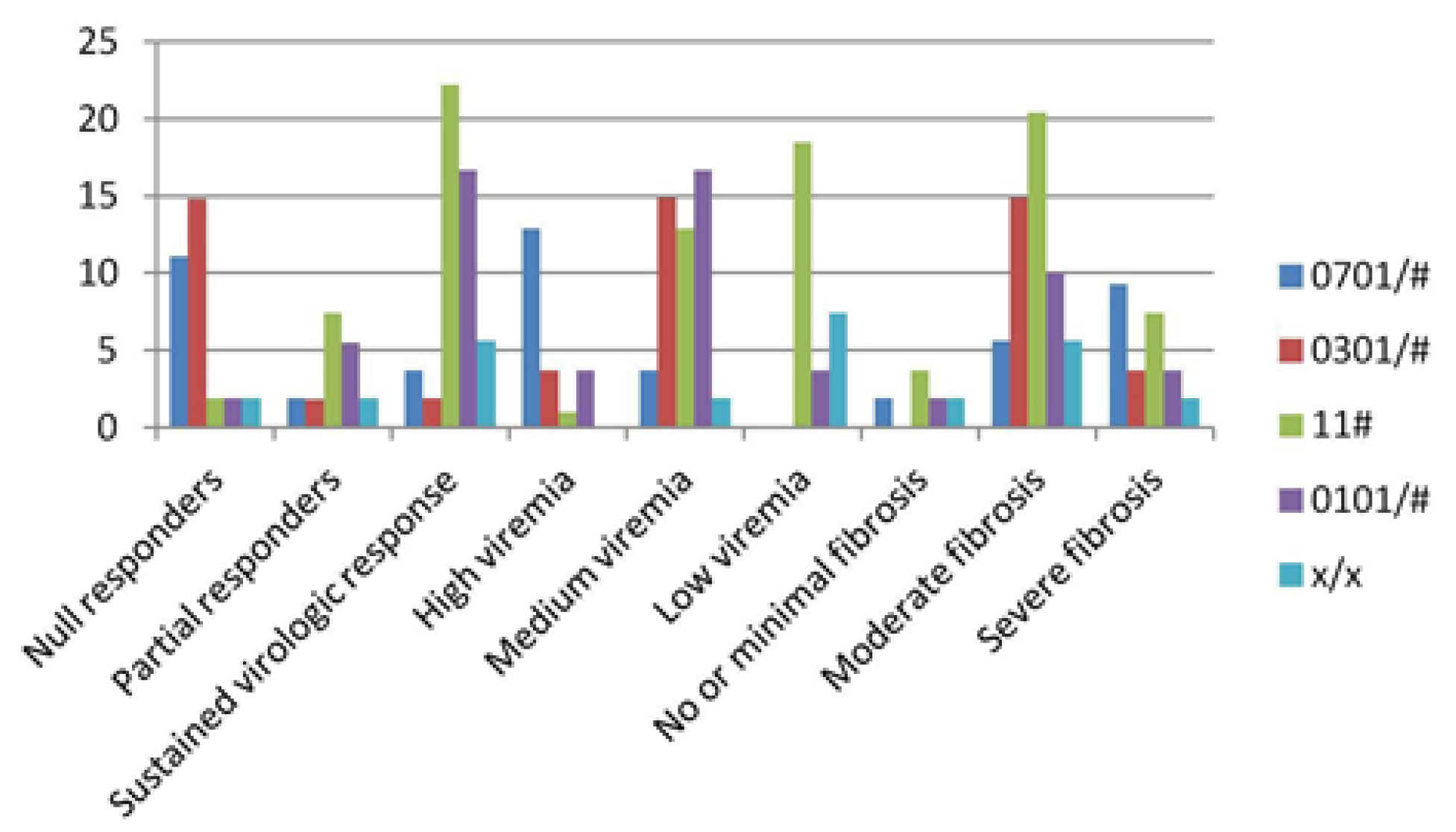

| DRB1*genotypes | 0701/# 0301/# (n= 9) (n=10) | 11# (n=17) | 0101/# (n=13) | x/x (n=5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Therapeutic response | |||||

| Null responders (%) | 11.1 | 14.8 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.9 |

| Partial responders (%) | 1.9 | 1.8 | 7.4 | 5.5 | 1.9 |

| Sustained virologic responders (%) | 3.7 | 1.9 Viral load | 22.2 | 16.7 | 5.6 |

| High viremia (%) | 12.9 | 3.7 | 1 | 3.7 | - |

| Medium viremia (%) | 3.7 | 14.9 | 12.9 | 16.7 | 1.9 |

| Low viremia (%) | - | - Fibrosis score | 18.5 | 3.7 | 7.4 |

| No or minimal fibrosis (%) | 1.9 | - | 3.7 | 1.9 | 1.9 |

| Moderate fibrosis (%) | 5.6 | 14.9 | 20.4 | 10 | 5.6 |

| Severe fibrosis (%) | 9.3 | 3.7 | 7.4 | 3.7 | 1.9 |

© GERMS 2015.

Share and Cite

Gheorghe, L.; Rugină, S.; Dumitru, I.M.; Franciuc, I.; Martinescu, A.; Balaș, I. HLA Class II Alleles in Romanian Patients with Chronic Hepatitis C. Germs 2015, 5, 44-49. https://doi.org/10.11599/germs.2015.1070

Gheorghe L, Rugină S, Dumitru IM, Franciuc I, Martinescu A, Balaș I. HLA Class II Alleles in Romanian Patients with Chronic Hepatitis C. Germs. 2015; 5(2):44-49. https://doi.org/10.11599/germs.2015.1070

Chicago/Turabian StyleGheorghe, Loredana, Sorin Rugină, Irina Magdalena Dumitru, Irina Franciuc, Alina Martinescu, and Iulia Balaș. 2015. "HLA Class II Alleles in Romanian Patients with Chronic Hepatitis C" Germs 5, no. 2: 44-49. https://doi.org/10.11599/germs.2015.1070

APA StyleGheorghe, L., Rugină, S., Dumitru, I. M., Franciuc, I., Martinescu, A., & Balaș, I. (2015). HLA Class II Alleles in Romanian Patients with Chronic Hepatitis C. Germs, 5(2), 44-49. https://doi.org/10.11599/germs.2015.1070