Case report

A 57-year-old man, who worked as a waste picker, presented to the emergency department with a 1-month history of progressive hypogastric pain, dysuria, and urgency. He had previously received antibiotic treatment on two occasions at another healthcare facility (the specific names of antibiotics used were not known). The patient denied any known comorbidities, allergies, or vaccinations. Notably, he reported a history of weekly alcohol, cigarette, and cocaine consumption. Additionally, he had experienced adynamia, weight loss, intermittent fever, and cough with sputum for the past 3 months. On physical examination, the patient appeared malnourished, with a body mass index of 17.2 kg/m2. He exhibited normal vital signs. On auscultation, there were bilateral lung crackles. Abdominal palpation revealed generalized tenderness. Additionally, in the rectal digital exam, the prostate was noted to be nodular and painful.

Laboratory tests revealed elevation of Creactive protein levels (121.4 mg/dL) and altered kidney function (blood urea nitrogen 25.5 mg/dL, creatinine 1.55 mg/dL and an estimated glomerular filtration rate of 52 mL/min/1.73m2). The white blood cell and platelet counts showed no abnormalities (leukocytes 9550 x 103/µL and platelets 451,000/µL). The patient had moderate anemia (hemoglobin 9.1 g/dL, mean corpuscular volume 86.6 fL). Additional investigations included a positive result for fourth-generation HIV test. He had a CD4 cell count of 111/mm3 and an HIV viral load of 1,715,225 copies/mm3. Testing for hepatitis B and C, and cryptococcosis yielded negative results. Non-treponemal test was positive with a titer of 1:32 dilutions, with negative testing on cerebrospinal fluid. Initially, considering a urinary tract infection in an immunocompromised patient, treatment with piperacillin-tazobactam was prescribed.

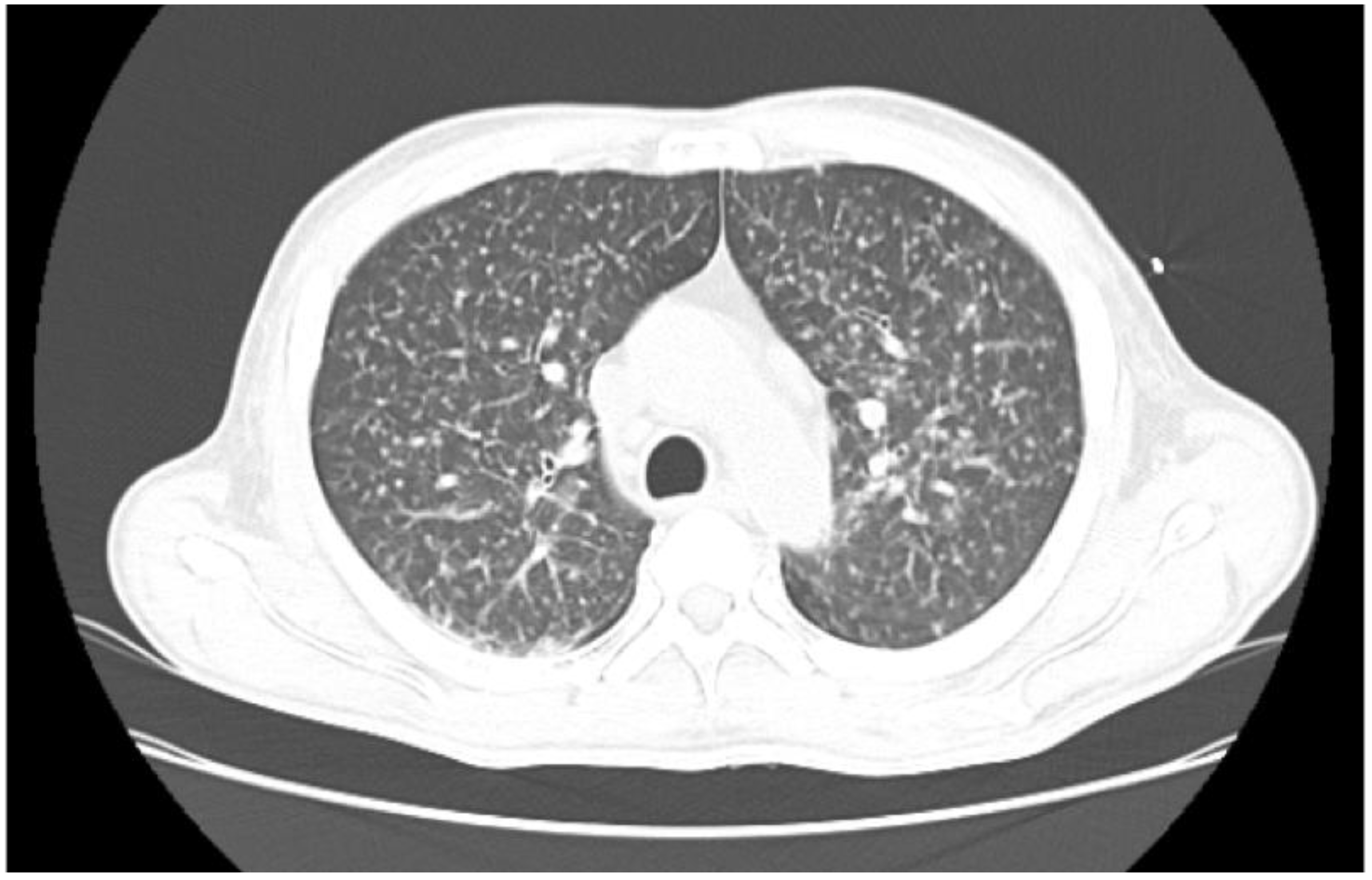

A lung computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a miliary pattern (

Figure 1).

M. tuberculosis was confirmed via real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) GeneXpert

® and Mycobacterial Growth Indicator Tube (MGIT) culture testing on sputum. Abdominal CT scans revealed an 18-cc abscess affecting the prostate and the right seminal vesicle (

Figure 2). Urine culture and RTPCR for

Chlamydia trachomatis and

Neisseria gonorrhoeae were negative. Transurethral drainage of the prostatic abscess was performed, and RTPCR of the sample identified

M. tuberculosis confirming the diagnosis of a tuberculosis prostate abscess. Susceptibility of

M. tuberculosis to rifampin by RT-PCR was documented.

The antituberculosis treatment regimen was initiated, consisting of rifampicin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol, in accordance with Colombia Health Ministry recommendations. Additionally, antiretroviral therapy with emtricitabine/tenofovir and dolutegravir was started 14 days later to prevent immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome, according to the national recommendations. The patient's condition and symptoms improved, leading to his eventual discharge. Information related to outpatient follow-up was not available.

Discussion

We have presented a case of a patient with de novo HIV infection with a prostate abscess caused by

M. tuberculosis. UGTB represents the third most common form of extrapulmonary tuberculosis [

1]. The likelihood of developing tuberculous kidney and prostate abscesses is higher in individuals living with HIV compared to those who are not infected [

2]. Prostatic tuberculosis typically presents as granulomatous prostatitis, and the formation of a prostatic abscess is an exceedingly rare occurrence [

1,

3]. Chronic inflammation and caseous necrosis caused during

M. tuberculosis infection can produce cavities and abscesses within the prostate [

2]. These abscesses can potentially drain into surrounding tissues, leading to the formation of fistulas in regions such as the perineum, urethra, or scrotum [

2].

Clinical findings in UGTB often include symptoms such as dysuria, nocturia, polyuria, and prostatic enlargement [

3,

4]. These symptoms may be accompanied by chronic pain in the flank and inguinal region, as well as sexual dysfunction [

4]. It is crucial to consider a broad range of differential diagnoses, including urinary tract infection, urethritis, epididymitis, prostatitis (commonly caused by microorganisms such as

Escherichia coli,

Proteus mirabilis,

Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and

Chlamydia trachomatis), spermatocele, and malignancy [

3,

4]. Furthermore, in cases of chronic epididymitis or prostatitis that do not respond to standard antibiotic treatments, consideration of potential genitourinary involvement should be warranted [

2]. In the present clinical case, urine culture and RT-PCR test for

N. gonorrhoeae and

C. trachomatis were negative. In addition, empiric antibiotic treatment was started to cover the most frequent bacterial pathogens until the final diagnosis of UGTB was reached.

While a combination of symptoms and imaging techniques can raise suspicion of urogenital tuberculosis (UGTB), microbiologic confirmation remains essential for an accurate diagnosis. Historically, diagnosis relied on biopsy histology and mycobacterial cultures [

1,

3,

4]. but modern molecular techniques are changing the diagnostic process, as in this case. In comparison to the current gold standard (MGIT culture), RTPCR exhibits excellent diagnostic performance, particularly for confirming the diagnosis. In urogenital tissues (renal, prostate, epididymis, penile, and soft tissue) samples, RT-PCR demonstrates a sensitivity of 87.5% and specificity of 86.7% [

5]. In urine samples, its sensitivity ranges from 94.6% to 100%, while specificity falls between 86.5% and 100% [

6,

7].

Furthermore, a comprehensive Cochrane metaanalysis incorporated data from 13 studies involving patients with suspected genitourinary tuberculosis. These studies included 1199 specimens from urine or tissue biopsy [

8]. Among these studies, 8 did not report HIV status, 1 included HIV-negative patients, and 4 had between 1% and 10% of patients living with HIV. A meta-analysis revealed that RT-PCR demonstrates a sensitivity of 82.7% and a specificity of 98.7% when diagnosing UGTB [

8]. These results underscore the reliability, performance and effectiveness of RT-PCR for UGTB diagnosis.

The primary objectives of UGTB treatment encompass eradicating the infection through antituberculous agents, managing complications, and addressing comorbidities and associated risk factors [

2]. Pharmacological therapy for UGTB closely mirrors that of pulmonary TB, with a standard 6-month duration of treatment recommended globally [

9]. Despite this, there is a notable absence of randomized controlled trials investigating the optimal treatment duration for UGTB. Surgical intervention becomes necessary in approximately 50% of patients during or after pharmacological treatment to achieve cure. The standard management protocol for these patients should invariably involve drainage of the prostatic abscess [

10]. as exemplified in our case. Otherwise, antiretroviral therapy is necessary to reduce morbidity and mortality in people living with HIV, and preventive therapy with isoniazid reduces the risk of tuberculosis in populations with both early and advanced HIV disease. It is important to rule out active tuberculosis before preventive treatment with isoniazid can be administered.