Introduction

Actinotignum schaalii is a Gram-positive coccobacillus and is a member of the normal microbiota [

1]. Among older adults and people with underlying structural and functional urological anomalies

A. schaalii is considered as an emerging pathogen leading to urinary tract infections (UTIs) and urosepsis [

2].

It is challenging to identify

A. schaalii in urine using standard microbiology laboratory procedures. It is frequently misidentified as a member of the skin microbiota, such as

Corynebacterium spp., and disposed as a contamination. It grows slowly in enriched blood agar media in 5% CO

2 or an anaerobic atmosphere as a facultative anaerobe. Molecular techniques like 16s rDNA sequencing and/or proteomics-matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization or advanced expert systems like Vitek2 may be necessary for identification [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5].

A. schaalii is susceptible to almost all betalactam antibiotics, but is inherently resistant to co-trimoxazole (TMP-SMX) and fluoroquinolones [

2,

3]. TMP-SXT and ciprofloxacin are commonly used empiric antimicrobials for patients with recurrent UTIs and culture-negative UTIs, and the risk of treatment failure would be higher if infected with

A. schaalii [

2].

Here we describe a young man with ureteric calculus who presented with A. schaalii pyelonephritis.

Case report

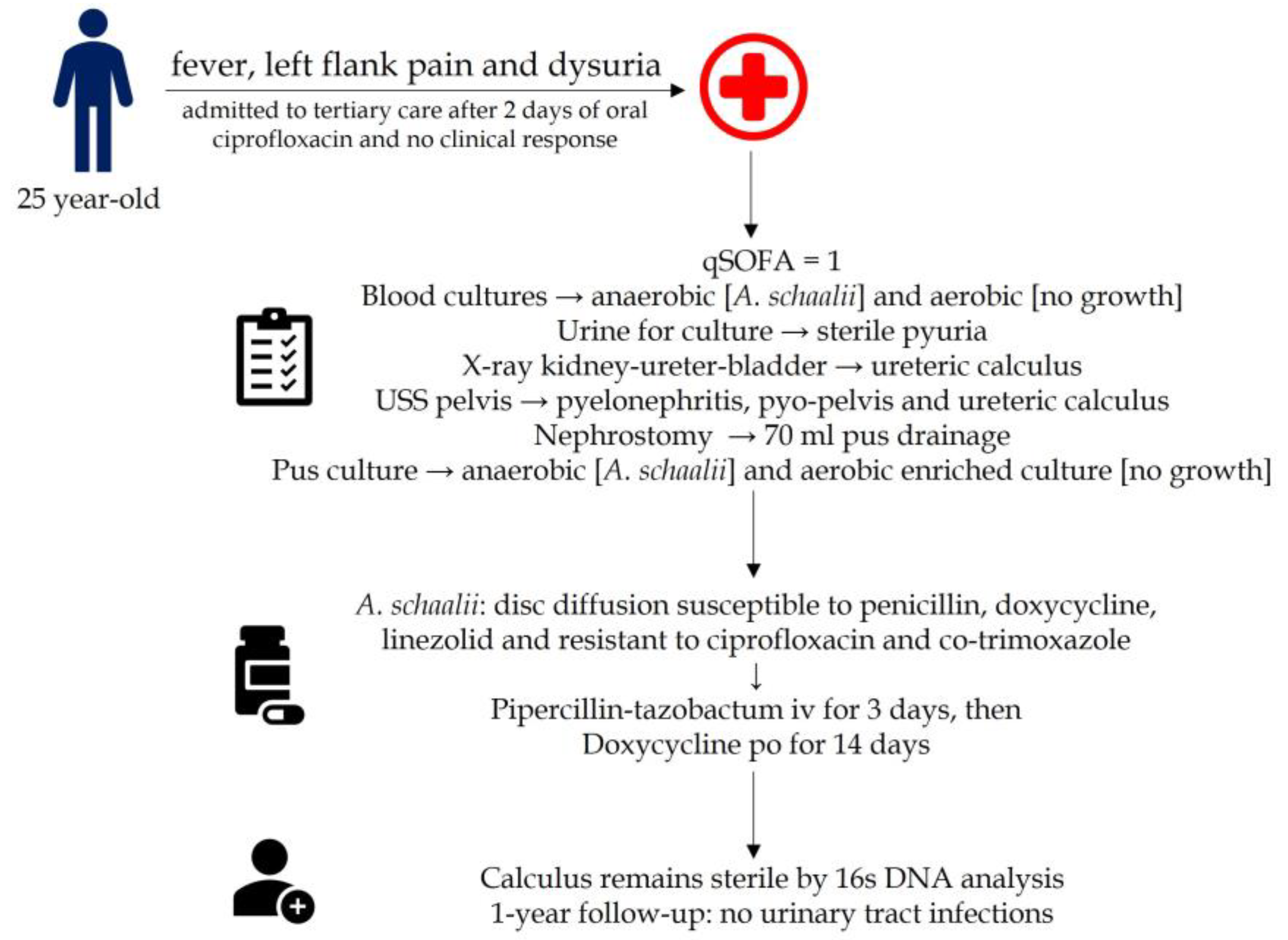

A previously well 24-year-old male presented to a tertiary care unit with fever, left flank pain, and dysuria for two days. He was initially treated with empiric oral ciprofloxacin by the general practitioner while pending a urine culture.

On admission, he looked ill and febrile. The abdominal examination revealed left flank tenderness. His pulse rate was 104 beats/min and his blood pressure was 110/70 mmHg. The rest of the clinical examination was unremarkable. The quick sequential organ functional assessment (qSOFA) score was 1, and he was transferred to the high dependency unit for further management.

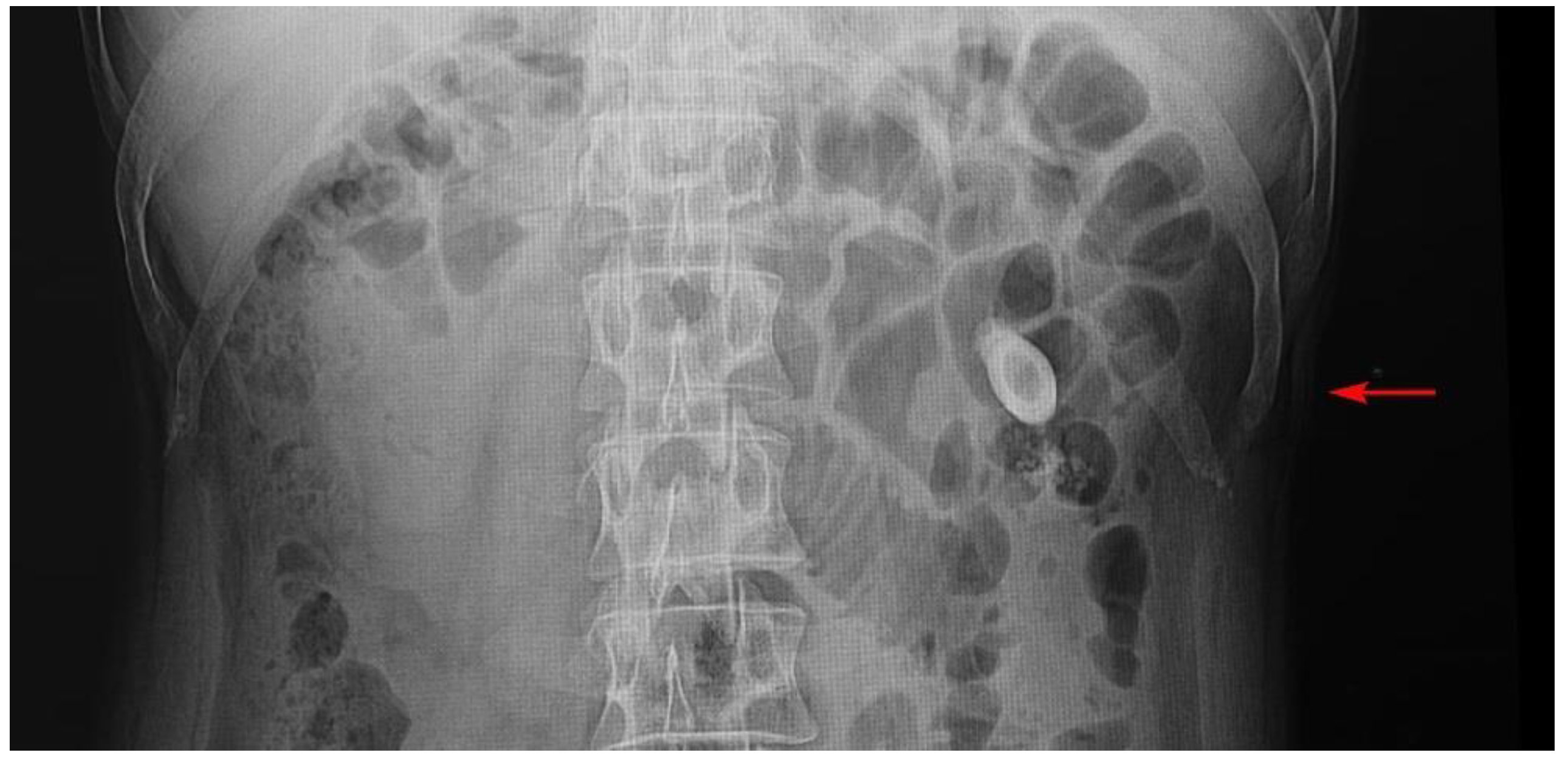

Blood cultures and urine cultures were done and empirical intravenous (IV) piperacillintazobactam was started. His on-admission Creactive protein (CRP) was 231 mg/L and his full blood cell count was 23.1 cells/µL with neutrophil leukocytosis [19.3 cells/µL]. His urine output was normal and the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was >90 mL/min. His random and fasting blood sugar was 136 and 104 mg/L, respectively. The hemoglobin A1c was 5.6%. Ultrasound scan of the pelvis revealed leftsided pyelonephritis with pyo-pelvis and left ureteric calculi (

Figure 1). Also detected was a moderate hydronephrosis of the left kidney. A nephrostomy tube was inserted to relieve the obstruction which drained pus and was sent to microbiology laboratory in aerobic and anaerobic blood culture bottles for culture and antimicrobial susceptibilities.

Two days later blood culture flagged positive for Gram-positive bacilli from the anaerobic bottle and the urine culture remained negative. Following VITEK 2 anaerobic card and MALDITOF analysis (Bruker, USA), it was identified as

A. schaalii. Similarly, pus from an anaerobic culture bottle was flagged positive and identified as

A. schaalii by VITEK 2 anaerobic card and MALDI-TOF analysis. Urine culture remained negative, and the full report suggests sterile pyuria. Antimicrobial susceptibilities are done using the disc diffusion method, however, no interpretative criteria are available for this isolate in either Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute standards [

6]. or the EUCAST antimicrobial susceptibility database [

7]. Based on the CLSI Gram positive bacilli break points, the isolates were susceptible to penicillin including ampicillin, piperacillin-tazobactam and doxycycline, and resistant to ciprofloxacin, erythromycin, and co-trimoxazole. He was treated with IV piperacillin-tazobactam for three days and with the clinical improvement and CRP response (34 mg/L), piperacillin-tazobactam was stopped and he was discharged with oral doxycycline 100 mg 12 hourly for 14 days.

His ureteric calculus was removed two weeks following his episode of urosepsis and he was followed up at the urology clinic. The ureteric calculus was sterile following microbiology cultures and 16s DNA analysis. For about one year after the episode of pyelonephritis, he has not had urinary tract infections (

Figure 2).

Discussion

A. schaalii was formerly thought to be a urinary commensal. The entire genome was recently sequenced, revealing genes that code for attachment pili, which may facilitate urothelial colonization [

5]. It is considered as an emerging urinary pathogen commonly found in the elderly.

A. schaalii has already been detected in different regions in the world including Europe and North America [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. This would be the first case found in South Asia. Our patient was young, but had a ureteric calculus, which is an independent risk factor for developing urinary tract infections including pyelonephritis. Pyelonephritis due to

A. schaalii is rare among young adults and follows ureteric calculus. The finding of ureteric calculus is incidental and the patient had not had signs and symptoms suggestive of renal or ureteric calculus. The calculus was sterile and there may not be an association between developing renal calculi and

A. schaalii infection. However, ureteric obstruction and edges of calculus, if sharp, can cause micro damage to the ureteric epithelium, thus ascending microorganisms when they reach the vicinity, can lead to the development of pyelonephritis and bacteremia [

4,

5,

8,

9].

Using VITEK 2 and MALDI-TOF, we were able to identify the blood culture isolate. However, the urine culture remained negative, and urine analysis suggested sterile pyuria. Because the organism grows in an anaerobic environment and therefore, by routine urine culture performed in aerobic and microaerobic incubations, may not grow, the chances of missing it are high. Also, it is a slow grower found as a Gram-positive bacillus, considered as a contaminant earlier [

4,

5,

8,

9,

10]. Ciprofloxacin and cotrimoxazole are commonly used to treat patients with urinary tract infections empirically and used as an oral step-down option following pyelonephritis and urosepsis. Here too he was initially treated with ciprofloxacin by a general practitioner and subsequently, the lack of response led to his admission to a tertiary care center.

Routine anaerobic urine culture is not done in patients with suspected urinary tract infections. Also, when found in blood, Grampositive bacilli grown in anaerobic or aerobic media are often considered as a contaminant unless the patient has a prosthesis [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

8]. However, urinary Gram staining would be helpful to provide information about

A. schaalii. Here urine Gram staining remained undetected, but pus obtained from the nephrostomy tube, which was incubated in an anaerobic environment, grew

A. schaalii.A. schaalii should be considered in cases of urinary tract infections among patients with structural and functional urinary tract anomalies. Processing the clinical specimens anaerobically and subsequently following the use of novel molecular, phenotypic, and proteomics diagnostics would be helpful to isolate the pathogen.

Conclusions

A. schaalii urinary tract infections including urosepsis are rare among young adults and patients with renal or ureteric calculi. The detection of A. schaalii is difficult as it is an anaerobic pathogen, and routinely, urine culture is not done using anaerobic media. The urine Gram staining may have a role in detecting and considering anaerobic media to isolate A. schaalii in patients with structural and functional urinary tract anomalies. Moreover, novel diagnostic platforms are important to speciate the pathogen. Also, the lack of pathogen-specific breakpoints for antimicrobial susceptibilities made it a problem to decide on appropriate therapy.

Author Contributions

JAASJ followed up the patient and drafted the manuscript. GRR has provided the supervision for the case management. Both authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of their case report and any accompanying images.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of interest

All authors—none to declare.

References

- Cattoir, V.; Varca, A.; Greub, G.; Prod'hom, G.; Legrand, P.; Lienhard, R. In vitro susceptibility of Actinobaculum schaalii to 12 antimicrobial agents and molecular analysis of fluoroquinolone resistance. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010, 65, 2514–2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lotte, R.; Lotte, L.; Ruimy, R. Actinotignum schaalii (formerly Actinobaculum schaalii): A newly recognized pathogen-review of the literature. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016, 22, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molitor, E. Obituary. Rev. Med Microbiol. 2016, 27, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beguelin, C.; Genne, D.; Varca, A.; et al. Actinobaculum schaalii: Clinical observation of 20 cases. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011, 17, 1027–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lotte, L.; Lotte, R.; Durand, M.; et al. Infections related to Actinotignum schaalii (formerly Actinobaculum schaalii): A 3-year prospective observational study on 50 cases. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016, 22, 388–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing, CLSI supplement M10, 31st ed; CLSI: Wayne, PA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST). Clinical breakpoints and dosing of antibiotics. Available online: https://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/EUCAST_files/Breakpoint_tables/v_14.0_Breakpoint_Tables.pdf.

- Gomez, E.; Gustafson, D.R.; Rosenblatt, J.E.; Patel, R. Actinobaculum bacteraemia: A report of 12 cases. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2011, 49, 4311–4313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loïez, C.; Pilato, R.; Mambie, A.; Hendricx, S.; Faure, K.; Wallet, F. Native aortic endocarditis due to an unusual pathogen: Actinotignum schaalii. APMIS. 2018, 126, 171–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kakodkar, P.; Hamula, C. A 2-year retrospective case series on isolates of the emerging pathogen Actinotignum schaalii from a Canadian tertiary care hospital. Microorganisms. 2022, 10, 1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]