Case report

A 38-year-old female with a history of insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus for the past 11 years, diabetic neuropathy, and depression came to the emergency room (ER) with complaints of nausea and vomiting. She also reported poor oral intake, fever, and chills along with epigastric abdominal pain and left shoulder pain for the past 2 weeks. The patient reported fevers with a maximum of 40 °C, responding to antipyretics at home. She had a history of recurrent urinary tract infections (UTI), and the most recent one was 2 months prior to presentation. Six days prior to this hospitalization, she presented to an emergency room with fever and abdominal pain, and she was prescribed amoxicillin-clavulanate for suspected urinary tract infection. Urine culture later showed mixed growth. She denied any history of intravenous drug abuse. On arrival she was normotensive, her temperature was 37.5 °C, her heart rate 103 beats/min, and her respiratory rate 22/min. The examination was significant for poor dentition and generalized abdominal tenderness, which was worse in the left upper quadrant.

Laboratory testing showed leukocytosis with a white blood cell count (WBC) of 14 ×10

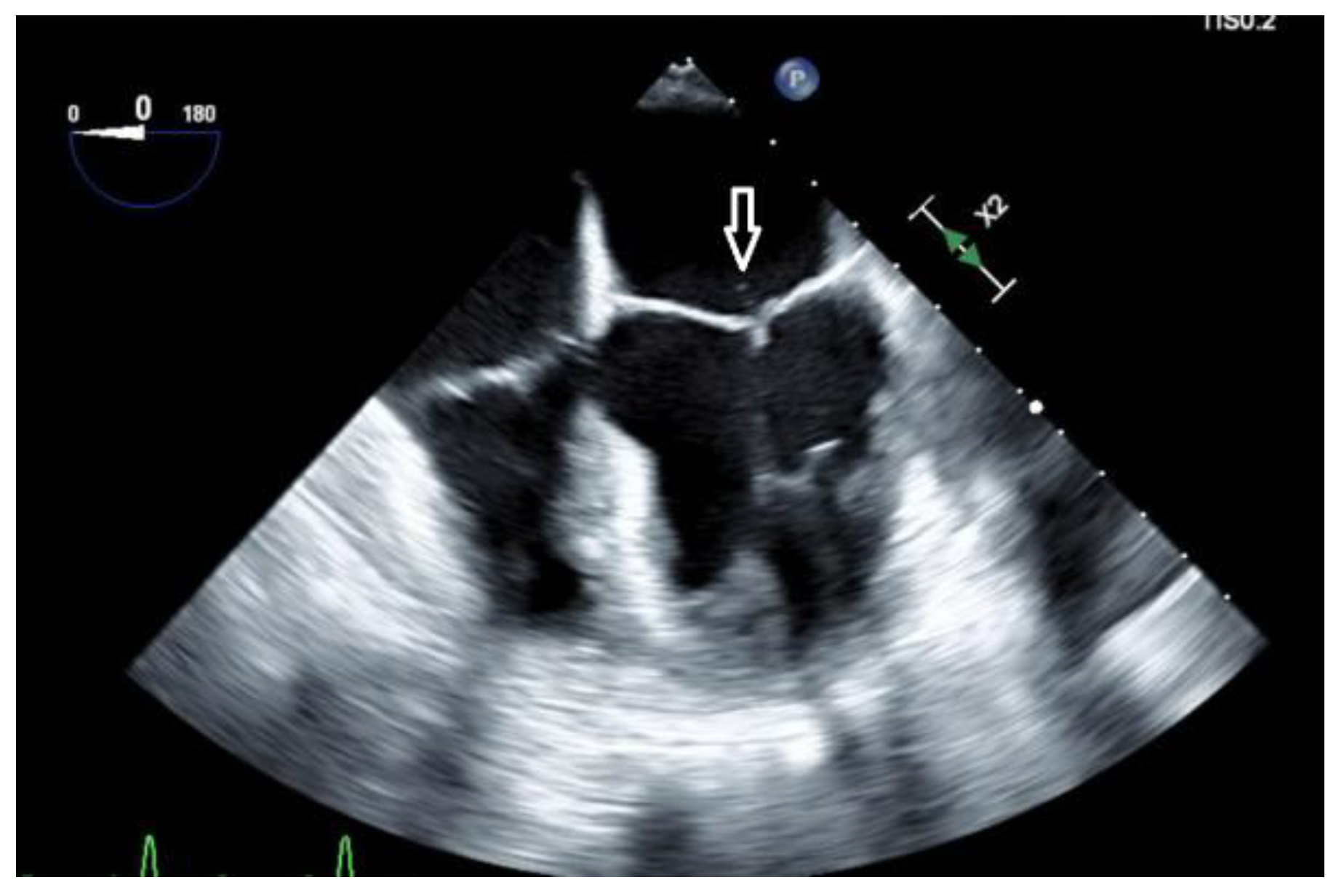

3/mcL with 91% neutrophils, pro-calcitonin elevated at 22.92 ng/mL, C-reactive protein (CRP) 19.37 mg/dL, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) 68 mm/h, hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) 12.2%. She was hyponatremic, hypokalemic, and hypochloremic with values of 133 mmol/L, 3.3 mmol/L, and 96 mmol/L, respectively. A computed tomographic (CT) abdominal scan with contrast showed multiple cystic masses in the spleen with concerns of developing splenic abscess (

Figure 1).

Ultrasound of the abdomen showed splenomegaly with multiple hypoechoic collections with the largest measuring up to 3.6 cm. Empiric treatment with intravenous piperacillin-tazobactam and fluconazole for fungal coverage was initiated. Blood cultures collected on admission did not show any growth in 5 days and urine culture showed contaminants. Extensive infectious disease workup including screening for HIV, syphilis, viral hepatitis, bartonellosis, brucellosis, Lyme disease, tick-borne illnesses, Chlamydia, and fungal antibody test was negative. Autoimmune disorder workup was negative including antinuclear antibody (ANA), antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA), lupus anticoagulant screen, and beta-2 glycoprotein antibody. Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) was negative for valvular vegetation. Blood next-generation sequencing of microbial cell-free DNA (NGS cfDNA) (“Karius Test”, Karius, USA) was ordered. As our patient continued to clinically deteriorate due to worsening sepsis in addition to post-procedure hemorrhage and the blood cultures obtained at admission had returned negative, a multidisciplinary team discussion was held and a decision was made to send out Karius test on the 7th day after admission. At this point, poor periodontal health was considered a possible source of infection and dental X-rays showed multiple dental caries. She continued to have low-grade fevers, but leukocytosis and abdominal pain improved. Antibiotics were switched to ceftriaxone 2 g daily intravenous (IV) dosing on the 4th day after admission. A CT-guided splenic fluid collection aspiration was done yielding 70 mL of blood-tinged purulent fluid and a drain was placed. Unfortunately, as a complication of the above-mentioned procedure, the patient developed splenic hemorrhage leading to hypotension and acute blood loss anemia for which she received intravenous fluids, fresh frozen plasma, and blood transfusions. Definitive control of blood loss was achieved by celiac and splenic CT angiogram and splenic artery embolization. Her WBC count worsened to 23 × 103/mcL and CRP to 23.23 mg/dL. Antibiotics were switched to cefepime 2 g every 8 hours and metronidazole 500 mg every 8 hours IV. Two days later she developed hypotension again, her hemoglobin had dropped to 6.5 mg/dL and there were concerns about continued splenic hemorrhage and hemoperitoneum. She underwent exploratory laparotomy with splenectomy. Surgical pathology showed splenic tissue with focal areas of abscess with necrosis and hemorrhage. Broad-range bacterial PCR (Mayo Clinic Laboratories, USA) of surgical specimens was negative. In the meanwhile, Karius test turned positive for Anaerococcus hydrogenalis. Karius test showed Anaerococcus hydrogenalis 184 DNA molecules per microliter (reference <10). No other organisms were detected.

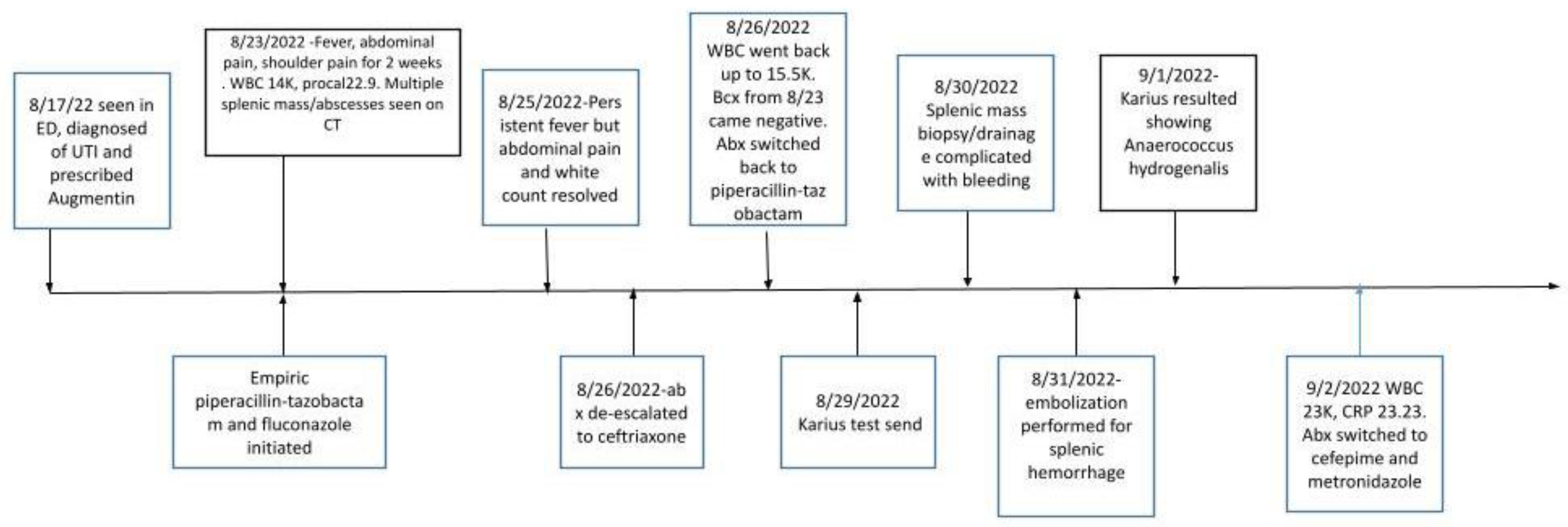

A trans-esophageal echocardiogram (TEE) showed a small mobile filamentous structure on the atrial side of the anterior mitral leaflet which was concerning for infective endocarditis (

Figure 2).

The patient eventually became hemodynamically stable. She successfully completed a 6-week course of cefepime every 8 hours IV and metronidazole 500 mg every 8 hours PO as an outpatient. A wider antibiotic coverage was given because of the complexity of the case, subsequent splenectomy and the presence of multiple dental caries. The timeline of events are depicted in

Figure 3.

Discussion

Blood culture-negative endocarditis (BCNE) is an infection of heart valves without isolation of culprit pathogens on blood culture by using traditional methods.

Coxiella burnetii is the most common organism causing culture-negative endocarditis, and serology can be used for diagnosis. Culture-negative IE is most commonly caused by antibiotic administration before blood culturing, especially in

Streptococcus viridans IE. Other pathogens of BCNE include

Bartonella,

Chlamydia,

Legionella,

Mycoplasma, and

Brucella species and these usually are diagnosed using polymerase chain reaction or serology.[

4]

The prior “modified Duke’s criteria” classified diagnosis as definitive, possible or rejected based on presence of major and minor criteria. Positive blood cultures, evidence of endocardial involvement and new valvular regurgitation are considered “major” criteria for diagnosis. The 2023 Duke-International Society for Cardiovascular Infectious Diseases (ISCVID) IE criteria recommend enzyme immunoassay, polymerase chain reaction (PCR), amplicon/metagenomic sequencing and in situ hybridization methods as new microbiologic minor criteria.[

5] Imaging such as PET CT and cardiac CT and intraoperative inspection are considered new major clinical criteria as well.[

5] Our patient had a vegetation noted on TEE (one major Duke criterion). She met three minor criteria with presence of fever, splenic abscess and NGS testing detecting an organism that can rarely cause IE. As per Fowler et al. “Amplicon or metagenomic sequencing has unresolved issues for the diagnosis of other causes of bacterial culture negative endocarditis (BCNE), including differentiating “true positive” from “contamination” and IE from other causes of bacteremia. Thus, positive serum amplicon or metagenomic sequencing results for organisms other than

C. burnetii,

Bartonella, and

Tropheryma whipplei bacteria should be considered as a Minor Criterion pending further data”.[

5] Our patient did not have any other identifiable source of sepsis other than BCNE, therefore, the positive NGS testing for

Anaerococcus hydrogenalis was considered a causative pathogen for IE. Haddad et al. performed a meta-analysis identifying 13 publications that used NGS for diagnosis of IE.[

6] NGS was considered a valuable tool for diagnosis of BCNE. As the authors state, it is a quicker method for diagnosis that can detect non-viable DNA and therefore it can be used in cases of prior antimicrobial use. They identified the test as a tool to detect previously unidentified pathogens, as in our case. The test still has limited availability, is expensive and can detect both dead and live pathogens, therefore result interpretation does need clinical correlation.[

6] Fortunately, this is an easily available test at our institution, with result turnover in around 72 hours.

A literature review published in 2019 analyzed 34 reported cases of GPAC-associated-IE. It was noted that GPAC-associated IE is more frequent in males, and in patients with prosthetic valves and often required surgical treatment for cure.[

7] Contrary to these findings, our patient was a young female with native valve endocarditis, which was successfully treated with antibiotics. However, she did have uncontrolled diabetes at the time of diagnosis which probably increased her risk of such infection.

GPACs account for 25-30% of all anaerobic bacteria from clinical specimens.

Anaerococcus,

Peptostreptococcus,

Finegoldia,

Peptoniphilus, and

Parvimonas are the most common GPAC genera associated with human infections.[

2] GPACs are known to cause soft tissue, bone, and female genital tract infections and are also commonly isolated in polymicrobial wound infections, and IE is rarely caused by GPACs, accounting for less than 1% of cases of IE.[

8]

The genus

Anaerococcus consists of Gram-positive, non-spore-forming, strictly anaerobic, non-motile cocci.[

9] They do not form any particular arrangement under the microscope and can be found in chains, pairs, tetrads, or even disorganized masses.[

9]

Anaerococcus was previously categorized under the genus

Peptostreptococcus. Anaerococcus hydrogenalis was initially grouped under

Peptostreptococcus group A-1 and was later re-classified as a new species called

Peptostreptococcus hydrogenalis in 1990 by Ekaki et al. It received the species name “

hydrogenalis” because, on gas chromatography, it produced large amounts of hydrogen from peptone-yeast extract medium and peptone yeast glucose broth (PYG). They metabolize peptones and amino acids with the major metabolic product of PYG being butyric acid and acetate.[

9]

The genus

Anaerococcus consists of 13 species and

A. prevotii. These bacteria are usually found in the vaginal, skin, and nasal flora and are usually isolated in polymicrobial abscesses.[

1,

9]

The first case of

A. octavius associated with bacteremia has been reported by Cobo et al. recently in the year 2019. In this case, the blood cultures grew Gram-positive cocci in anaerobic blood agar and the mass-spectrometry technique identified the strain as

Clostridium beijerinckii. On confirmatory testing with 16S rRNA sequence analysis, the species was identified as

A. octavius. Thus, a definitive and reliable diagnosis of anaerobic cocci species was made using molecular techniques.[

10] While proteomic techniques such as mass spectrometry are very useful and heavily used, their limitation is that the organism will be identified only if the spectral database has the peptide mass fingerprints.[

11] Badri et all in their retrospective population based study, reported 43 cases of bacteremia due to

Anerococcus.[

12]

Identification of GAPCs via traditional laboratory techniques is difficult because of meticulous sample collection requirements, long incubation time, sensitivity to oxygen, tedious phenotypic identification process, and considerable changes in the taxonomy over the years with the addition of new species often leading to inconclusive species identification. GPACs are often isolated in polymicrobial samples and thus often are overlooked in terms of clinical significance.[

8] Nevertheless, newer molecular diagnostic techniques like PCR, mass spectrometry, 16s rRNA sequencing, and cell-free microbial DNA testing (Karius Test) now help in the more precise identification of these largely understudied organisms.[

3,

8]

Karius test is a commercially available metagenomic next-generation sequencing test that can identify cell-free microbial DNA from over 1,200 pathogens, which was useful in the identification of the organism causing IE in our patient. The advantages of NGS include its ability to detect cfDNA of DNA viruses, fungi, and protozoa in plasma, both in cases of localized or systemic infection.[

3] It has also been shown that NGS can detect fastidious infection despite prior use of antibiotics, keeping in mind that the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics prior to obtaining appropriate culture can significantly reduce the sensitivity of the test.[

13]

GPACs including

Anaerococcus species are traditionally susceptible to penicillins although reports of resistance to tetracycline, erythromycin, levofloxacin, and clindamycin have been communicate.[

7] In our patient, due to poor dentition, a decision was made to treat broadly for polymicrobial infection (including anaerobes), and the patient was treated with cefepime and metronidazole for 6 weeks. Due to blood cultures remaining negative, antibiotic susceptibility testing was not possible.