Abstract

Introduction: Intravesical Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) instillation is the most effective adjuvant therapy for superficial urinary bladder carcinoma, prolonging disease-free survival. Although it is usually well tolerated, moderate to severe local or systemic infectious complications, including sepsis involving multiple organs, may occur. Case report: We report the unusual case of a man in his mid ‘70s who presented with septic shock and severe acute respiratory failure requiring intubation. Lack of response to antibiotics, history of intravesical BCG instillation and consistent imaging findings led to further investigations, with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid polymerase chain reaction (PCR) results indicating pneumonitis due to Mycobacterium bovis dissemination. Prompt anti-tuberculosis treatment combined with corticosteroids resulted in significant clinical and radiological improvement, supporting the diagnosis of disseminated BCG infection. Conclusions: Due to its non-specific clinical presentation and the relatively low diagnostic yield of conventional microbiological tests, a high index of suspicion is required for prompt diagnosis and treatment of systemic BCG infection. PCR-based assays for mycobacterial DNA identification may represent a valuable tool facilitating timely diagnosis of this uncommon, yet potentially life-threatening infection.

Introduction

Intravesical instillation of bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG), the attenuated live strain of Mycobacterium bovis, is the most effective adjuvant therapy for patients with non-invasive urinary bladder carcinoma (NIBC), prolonging disease-free survival.[1] Although usually well tolerated, local as well as systemic BCG-related adverse reactions after instillation have been reported, with serious side effects (including granulomatous prostatitis, pneumonitis, hepatitis and sepsis) being encountered in less than 5% of patients.[2] Risk factors for hematogenous spread of BCG bacilli during intravesical instillation include disruption of the urothelial barrier due to traumatic catheterization, early instillation after transurethral bladder resection and concurrent urinary tract infection.[1] The reported incidence of BCG infections after bladder instillations is approximately 1%, with extra-pulmonary BCG infections being significantly more frequent than pulmonary.[3] In rare instances life-threatening BCG sepsis associated with multiple organ failure may occur,[4] requiring a high index of suspicion by treating physicians. We report the case of a 73-year-old man who was admitted to the ICU with sepsis and severe acute respiratory failure following BCG instillation and discuss challenges in prompt diagnosis of Mycobacterium bovis dissemination.

Case report

A 73-year-old male non-smoker with a history of superficial bladder carcinoma under adjuvant BCG immunotherapy was transferred to our hospital’s ICU due to sepsis and acute hypoxemic respiratory failure eight days after his BCG immunotherapy session. The patient’s symptoms had started approximately 48 hours following his last intravesical BCG instillation when he developed fever (up to 38.8°C), malaise and shortness of breath. The patient was initially admitted to the Department of Urology and was treated with meropenem and ciprofloxacin under a working diagnosis of complicated urinary tract infection (UTI).

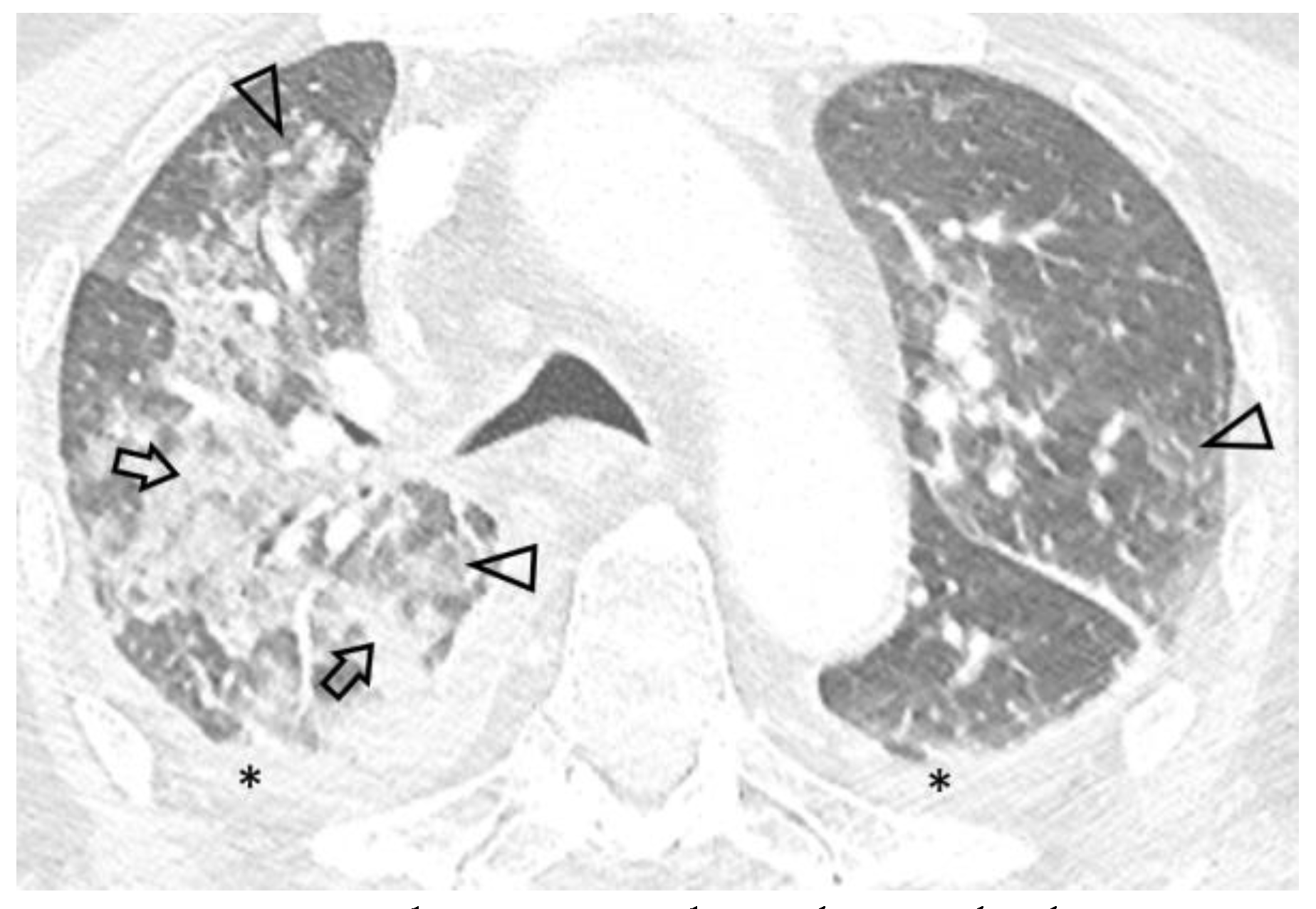

Due to worsening hypoxemic respiratory failure, the patient was transferred to our hospital’s ICU. On admission the patient was febrile (38.3°C), hemodynamically unstable (arterial blood pressure 90/65 mmHg) and in respiratory distress, with bilateral inspiratory rales. Arterial blood gas analysis revealed hypoxemia with respiratory alkalosis (FiO2 0.50, pH 7.46, partial pressure of oxygen 58 mmHg, partial pressure of carbon dioxide 33 mmHg, HCO3 23 mmol/L). Laboratory tests revealed pancytopenia (hemoglobin 11.8 g/dL, white blood cells 3200/μL, platelets 54000/μL), increased C-reactive protein (15.9 mg/dL) and procalcitonin (1.11 ng/mL) levels, hematuria, leukocyturia and mild proteinuria. Serological tests for viral hepatitis and human immunodeficiency virus were negative, as well as markers of immune-mediated disease (antinuclear, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic, anti-glomerular basement membrane and anti-streptolysin O antibodies), while remaining laboratory findings were unremarkable. Chest X-ray on admission showed ill-defined alveolar infiltrates, while thoracic CT demonstrated extensive ground-glass opacities, as well as localized alveolar opacities of all lobes with a predominant peri-broncho-vascular distribution (Figure 1). Small pleural effusions were also noted. Differential diagnosis based on imaging and provided history mainly included a) acute respiratory distress syndrome due to complicated UTI, b) pulmonary infection and c) BCG-related complication.

Figure 1.

Axial 0.6 mm slice through the upper lung fields demonstrates asymmetric ground glass (arrowheads) and alveolar (arrows) opacities with a centrilobular distribution. Bilateral pleural effusion (*) is also seen.

Specimens for blood, urine and sputum cultures were collected and empirical broad-spectrum antibiotic treatment was continued. Due to worsening hypoxemia and respiratory distress not responding to non-invasive mechanical ventilation the patient was intubated on ICU day 2. Multiple bacterial and fungal blood, urine and sputum cultures were negative, as well as sputum acid-fast stains for mycobacteria and serum interferon-gamma release assay (QuantiFERON®). On ICU day 4, flexible fiberoptic bronchoscopy with broncho-alveolar lavage fluid (BALF) collection for microbiology and cytopathological analysis was performed, which yielded a positive real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) result for Mycobacterium bovis DNA, while BALF PCR for Aspergillus, as well as BALF immunofluorescence assay for Pneumocystis jirovecii were negative. Thus, the diagnosis of disseminated BCG infection was established and was subsequently confirmed by positive BALF culture for M. bovis ssp. Anti-tuberculosis treatment including isoniazid 300 mg, rifampin 600 mg and ethambutol 1500 mg combined with intravenous prednisolone 50 mg once daily was initiated, while broad-spectrum antibiotic treatment was terminated. Within two weeks of anti-tuberculosis treatment, marked improvement in clinical and laboratory status was achieved and the patient’s respiratory failure resolved, allowing successful weaning from mechanical ventilation.

On ICU Day 56 the patient was discharged and transferred to the Department of Thoracic Medicine. A six-month anti-tuberculosis treatment was completed.

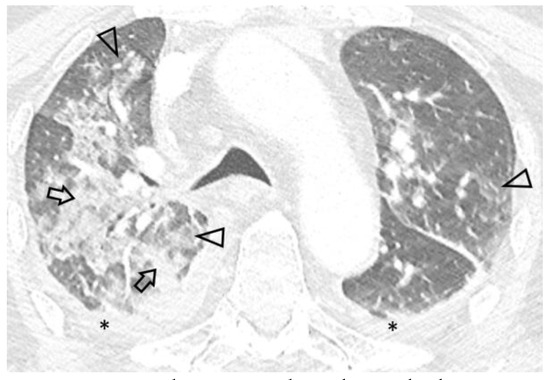

A follow-up chest CT performed five months after diagnosis showed significant improvement of pulmonary disease with subtotal resolution of pre-existing ground-glass opacities and increased pleural effusions (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Axial 0.6 mm slice, level similar to Figure 1, demonstrates subtotal resolution of opacities with residual centrilobular ground glass nodules (arrowheads) and increased left pleural effusion, extending into the major fissure (*).

Discussion

BCG is a vaccine against tuberculosis developed by Albert Calmette and Camille Guérin. This attenuated live strain of Mycobacterium bovis with its lost virulence but retained antigenicity has been proven to be the most effective adjunctive therapy for non-invasive urothelial bladder cancer.[1] The precise immunological mechanism underlying BCG therapy has not yet been fully characterized. BCG immunotherapy has been suggested to exert its complex anti-tumor actions by three distinct mechanisms: infection of urothelial cancer cells, induction of anti-tumor effects and, most importantly, initiation of immune reactions, which are characterized by local immune activation involving multiple cytokines and local migration of polymorphonuclear cells, ultimately resulting in tumor cell death.[5] Of note, the presence of genetic divergence in distinct BCG strains has been associated with differences in elicited immune responses without, however, being clear if such changes might translate into significant clinical impact. This uncertainty was confirmed in a recent meta-analysis by Del Giudice et al.[6] studying the comparative efficacy of different BCG strains in bladder cancer treatment, where no clinically relevant difference was noted.

Although BCG immunotherapy is usually well tolerated without causing significant morbidity, local or systemic complications varying from self-limited irritative voiding symptoms to life-threatening sepsis may arise. In a series of 2026 patients Lamm et al. reported a 4.8% incidence of major systemic complications, which among others included hepatitis and pneumonitis (0.7%), cytopenia (0.1%) and sepsis (0.4%), while distant organ involvement manifesting as osteomyelitis, mycotic vascular infections or endophthalmitis, was less common.[2]

Disseminated BCG infection following BCG immunotherapy, presenting as either pulmonary infection or sepsis is extremely rare. A recent nationwide cohort study from Denmark including 6753 patients reported a BCG-related infection incidence of 1%, with pulmonary BCG infections and sepsis representing 30% and 3% of those cases, respectively.[3] The combination of these two conditions, as presented here, might be even less common. Pulmonary involvement may manifest either as a result of hematogenous spread of M. bovis, mimicking miliary tuberculosis[7] or, more frequently, as interstitial pneumonitis with bilateral ground-glass opacities on chest imaging.[8] In addition to his severe hypoxemic respiratory failure, our patient presented with septic shock. Although life-threatening BCG sepsis is rare, estimated to affect approximately 1 in 3000 patients treated with BCG immunotherapy,[3] its presence should be suspected in any patient who, following intravesical BCG instillation, develops fever and hypotension with potential progression to multi-organ failure.

The pathogenetic mechanism by which BCG immunotherapy leads to the development of disseminated BCG-related disease is not entirely understood. It is still debated whether systemic complications are the result of an immunological reaction, i.e., granulomatous inflammation or of an active infection. The presence of granulomas in various tissues in the absence of positive acid-fast stains, culture and PCR testing for mycobacterial DNA, as reported in some cases, might indicate a hypersensitivity reaction to BCG’s immune-stimulating effect,[9] which could explain the favorable response to treatment with corticosteroids. Contrary to this, in other cases, like ours, existence of viable mycobacteria in various biological specimens was demonstrated,[10] supporting the theory of hematogenous systemic infection due to urinary bladder epithelial disruption. Probably both aforementioned mechanisms coexist, contributing to the pathogenesis of systemic complications.

Laboratory confirmation of disseminated BCG-related disease can be challenging. In our patient, acid-fast stains for mycobacteria and QuantiFERON® were negative on ICU day 2, while the correct diagnosis was based on M. bovis DNA identification in BALF by real-time PCR and was subsequently confirmed by positive BALF culture for M. bovis ssp. Positive cultures for M. bovis are infrequently reported in patients with lung involvement. Diagnostic performance rates for acid-fast bacilli staining, conventional mycobacterial culture and PCR-based assays in the cohort of Perez-Jacoiste Asin et al. were 25.3%, 40.9% and 41.8%, respectively.[4] Consequently, even when all conventional microbiological tests yield negative results, this does not exclude the possibility of BCG infection. Regarding PCR-based assays, using a highly sensitive and specific real-time PCR assay for M. tuberculosis complex identification in blood specimens of ten patients undergoing BCG instillation, Siatelis et al. were able to detect BCG bacteremia in the two cases with systemic complications (fever and fatigue), while the remaining patients who were negative for BCG bacteremia presented no fever or other systemic signs, indicating that early detection of mycobacterial DNA in blood or BALF specimens using a real-time PCR protocol may aid the treating physician in diagnosing a probable systemic BCG infection.[11]

There are no established guidelines for the treatment of BCG infection. Current evidence supports a three-drug anti-tuberculosis regimen including rifampicin, isoniazid and ethambutol for a minimum of six months, while addition of systemic corticosteroids may be necessary in severe cases of systemic BCG infection according to practice recommendations by the European Association of Urology.[1] In our patient, prednisolone added to anti-tuberculous therapy resulted in quick resolution of septic shock and respiratory failure.

Conclusions

Systemic BCG infection is a rare, but potentially life-threatening complication of BCG immunotherapy in patients with superficial bladder cancer. This diagnosis must be taken into consideration in every patient presenting with constitutional symptoms while receiving such treatment, even when initial diagnostic workup yields negative results. PCR-based assays for mycobacterial DNA identification may be a valuable diagnostic tool for early detection of systemic BCG infection. Physicians managing BCG-treated patients should exhibit a high index of suspicion and clinical awareness to recognize and manage this severe complication.

Author Contributions

Conception and design: DM, EK. Acquisition of data: CP, EP. Analysis and interpretation of data: EK, MR. Drafting of the manuscript: DM. Revision of the manuscript: EK, MR. Final approval of manuscript: DM, EK, CP, MR, EP. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

None to declare.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors – none to declare.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report and the accompanying images.

References

- Babjuk, M.; Burger, M.; Capoun, O.; et al. European Association of Urology Guidelines on Non-muscleinvasive Bladder Cancer (Ta, T1, and Carcinoma in Situ). Eur Urol. 2022, 81, 75–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamm, D.L.; van der Meijden, P.M.; Morales, A.; et al. Incidence and treatment of complications of bacillus Calmette-Guerin intravesical therapy in superficial bladder cancer. J Urol. 1992, 147, 596–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsen, E.; Nordholm, A.; Lillebaek, T.; Holden, I.; Johansen, I. The epidemiology of bacille Calmette-Guérin infections after bladder instillation from 2002 through 2017: a nationwide retrospective cohort study. BJU Int. 2019, 124, 910–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Jacoiste Asín, M.; Fernández-Ruiz, M.; López-Medrano, F.; et al. Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) infection following intravesical BCG administration as adjunctive therapy for bladder cancer: incidence, risk factors, and outcome in a single-institution series and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2014, 93, 236–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, D.B.; Siref, L.E.; Feloney, M.P.; Hauke, R.J.; Agrawal, D.K. Immunological basis in the pathogenesis and treatment of bladder cancer. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2015, 11, 265–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Giudice, F.; Asero, V.; Bologna, E.; et al. Efficacy of different bacillus of Calmette-Guérin (BCG) strains on recurrence rates among intermediate/high-risk nonmuscle invasive bladder cancers (NMIBCs): single-arm study systematic review, cumulative and network metaanalysis. Cancers (Basel). 2023, 15, 1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colmenero, J.; Sanjuan-Jimenez, R.; Ramos, B.; Morata, P. Miliary pulmonary tuberculosis following intravesical BCG therapy: case report and literature review. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012, 74, 70–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caramori, G.; Artioli, D.; Ferrara, G.; et al. Severe pneumonia after intravesical BCG instillation in a patient with invasive bladder cancer: case report and literature review. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2013, 79, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Delimpoura, V.; Samitas, K.; Vamvakaris, I.; Zervas, E.; Gaga, M. Concurrent granulomatous hepatitis, pneumonitis and sepsis as a complication of intravesical BCG immunotherapy. BMJ Case Rep. 2013, 2013, bcr2013200624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewandowska, K.; Lewandowska, A.; Baranska, I.; et al. Severe respiratory failure due to pulmonary BCGosis in a patient treated for superficial bladder cancer. Diagnostics (Basel). 2022, 12, 922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siatelis, A.; Houhoula, D.P.; Papaparaskevas, J.; Delakas, D.; Tsakris, A. Detection of bacillus Galmette-Guérin (Mycobacterium bovis BCG) DNA in urine and blood specimens after intravesical immunotherapy for bladder carcinoma. J Clin Microbiol. 2011, 49, 1206–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© GERMS 2023.