Abstract

Introduction: Tuberculosis is currently undergoing a worrying recovery in Morocco. It is becoming a tropical disease again and can take deceptive clinical forms and involve unusual localizations. We report a rare case of pancreatic abscess due to Mycobacterium tuberculosis in an immunocompromised patient. Case report: The patient was 48 years old and was diagnosed with HIV infection 16 months previously during a systematic check-up. He had no notable pathological history, no notion of tuberculosis contagion and no signs of tuberculosis impregnation, and was admitted for the management of epigastric pain associated with an altered general condition. Abdominal CT scan showed a bulbar perforation and multiple deep necrotic adenopathies of infectious or tumoral origin. Direct examination of the pus with Ziehl Neelsen stain was positive (1-10 BAAR/field). Molecular study using the GeneXpert MTB/RIF technique revealed M. tuberculosis complex without rifampicin resistance. The patient was put on antibacillary treatment based on isoniazid, rifampicin, ethambutol and pyrazinamide. The patient died of septic shock with multiple organ failure. Conclusions: The diagnosis of a tuberculous pancreatic abscess may be overlooked because of its rarity and its clinical state simulating a pancreatic tumor, so it should be considered especially in endemic countries like ours.

Introduction

Tuberculosis is a global public health problem. The World Health Organization (WHO) reported 10.6 million new cases of TB with 89% of cases coming from adults (56.5% men and 32.5% women) and 11% from children in 2021. [1] Overall, there were 1.6 million deaths (including 187,000 co-infected with the human immunodeficiency virus—HIV) according to the same WHO report. [1] Globally, tuberculosis is the thirteenth leading cause of death and the second leading cause of death due to infectious disease, after COVID-19. [1] In Morocco, 29,018 new cases of tuberculosis, all forms combined, were recorded in 2020, including 240 cases co-infected with HIV. [2] The extra-pulmonary form represents nearly 1/3 of the tuberculosis cases reported in Morocco. [3] It occurs in decreasing order of frequency in the lymph nodes, genito-urinary, osteo-articular and neuro-meningeal areas. [3] Abdominal location is relatively frequent and represents 5 to 10% of all locations. [3] According to a multicenter study, the pancreatic localization had a rate that varied from 0% to 4.7%. [4] This is an unusual presentation with a polymorphic and non-specific symptomatology. We report a rare case of a fatal tuberculous abscess in a 48-year-old immunocompromised woman simulating a pancreatic tumor and we want to draw the attention of our physicians in front of any pancreatic lesion, to think of tuberculosis especially in an endemic country like ours.

Case report

The patient was 48 years old and had been diagnosed with HIV infection 16 months previously during a systematic check-up. He had no notable pathological history, no notion of tuberculosis contagion and no signs of tuberculosis impregnation, and was admitted for the management of epigastric pain associated with an altered general condition. The history of the disease went back 2 months when he had consulted a local doctor who had prescribed proton pump inhibitors. When these signs persisted, he came to our institution for specialized care. The clinical examination on admission revealed a conscious patient, apyretic, blood pressure 110/60 mmHg, with non-painful right cervical adenopathies, soft and mobile, and frank epigastric sensitivity without defense or contracture, accompanied by immediate postprandial vomiting and dizziness associated with uncalculated weight loss and pale conjunctiva without signs of hepatocellular insufficiency. Electrocardiogram revealed sinus tachycardia. Chest radiograph was normal. Biological examinations showed microcytic anemia at 9.5 g/dL and a nonspecific inflammatory syndrome with C-reactive protein (CRP) at 247 mg/L and ferritinemia at 3634 ng/mL, lipase at 51 IU/L without cytolysis or cholestasis. HIV-1/2 serology was positive with a CD4 count of 100/mm [3]. The viral load was 100,000 copies/mL of blood.

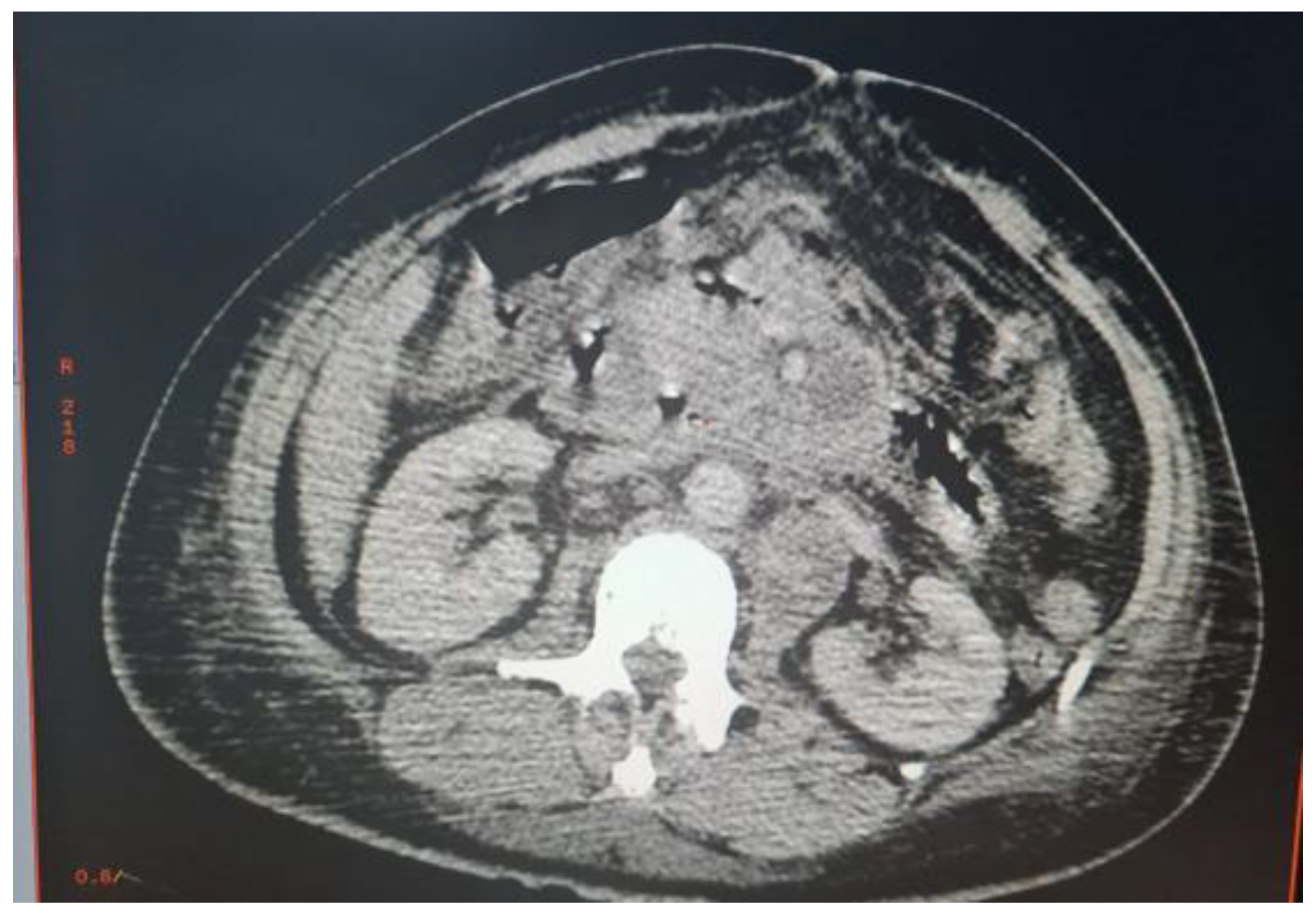

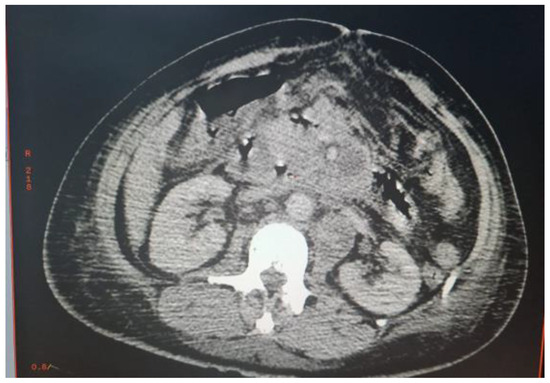

Abdominal CT scan showed a bulbar perforation and multiple deep necrotic adenopathies of infectious or tumoral origin. An exploratory laparotomy was decided (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Multiple deep necrotic intra and retroperitoneal adenopathies.

The procedures performed were a pancreatic abscess puncture for bacteriological study and an epiploon biopsy for anatomical-pathological study. The postoperative consequences were marked by hemodynamic instability and respiratory distress. The patient was transferred to the surgical intensive care unit where he was intubated and ventilated. A series of blood cultures composed of an aerobic and anaerobic bottle and a cytobacteriological examination of the urine were performed. CRP, procalcitonin and a complete blood count were also requested. When the inflammatory parameters increased (CRP 345 mg/L, procalcitonin 4 µg/L and white blood cells 22,000/mL), an i.v. antibiotic therapy based on ceftriaxone 1 g × 3 per day associated with gentamicin 160 mg per day was initiated. Direct examination of the pus with Ziehl Neelsen stain was positive (1-10 BAAR/field). Molecular study using the GeneXpert MTB/RIF technique revealed M. tuberculosis complex (MTBC) without rifampicin resistance. Cytobacteriological examination of urine was sterile and blood cultures were declared negative by the BD BACTECTM 9000 System (Becton Dickinson, USA) after 5 days of incubation. Cultures on liquid medium BACTECTM MGITTM (Mycobacterial Growth Indicator Tube) and solid medium Löwenstein-Jensen (LJ) were positive after 8 days and 21 days of incubation respectively. Sputum from 3 days old was negative for Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex by direct examination and GeneXpert MTB/RIF. Anatomopathological examination of the epiploon concluded the absence of malignant proliferation. The patient was put on antibacillary treatment based on isoniazid, rifampicin, ethambutol and pyrazinamide. The patient died of septic shock with multiorgan failure after 6 days of hospitalization.

Within the context of epidemiological surveillance of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex species, we performed molecular typing using multiplex real-time PCR as described below.

The extraction from the culture in solid medium LJ was performed in two steps: the first step consisted of putting a few colonies in 50 µL of lysis buffer followed by shaking for a few seconds and incubation at 95 °C for 5 min. The second step consisted in adding 50 µL of neutralization buffer followed by shaking for a few seconds and centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 5 min. The supernatant was collected and used for amplification.

Typing of the different species of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex was done using real-time PCR.

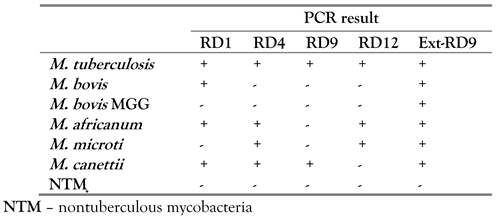

We performed two multiplex PCRs to detect the five regions present in the different species of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. The first multiplex PCR targeted three regions (RD1, RD4 and RD9). The second multiplex included two regions (RD12 and ext-RD9). [5]

We used the same primers and probes from the original protocol for RD1, RD4, RD9, RD12 and ext-RD9 as reported by Halse et al. [5] This assay was performed in a 25 µL volume using the Roche LightCycler-FastStart DNA Master Hybridization Probes kit (Roche Diagnostics Corporation, USA). Each reaction mixture consisted of 1 LightCycler-FastStart DNA Master Hybridization Probes mix, 4 mM MgCl2, 450 nM forward and reverse primers, 125 nM probes, sterile water, and 5 µL of DNA template. Thermocycling conditions were as follows: 1 cycle at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 45 cycles at 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 1 min. Thermocycling, fluorescence data collection, and data analysis were performed with a 7500 fast real-time PCR system (v. 2.0.2) (ABI) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, with the passive reference dye, ROX, turned off. [5]

Interpretation of MTBC-RD real-time PCR: a positive target result (cycle threshold (CT) value of <45) indicated that the RD was present, and a negative target result (CT value undetermined) indicated that the RD was absent. The resulting target patterns for each specimen were compared to the signature patterns in Table 1 to determine a match to the signature pattern for each species of MTBC. [5] Mycobacterium tuberculosis was the species detected by real-time PCR in our case.

Table 1.

Model of interpretation by species of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex [1].

Discussion

Abdominal localization is a relatively common extra-pulmonary form of tuberculosis, accounting for 5-10% of all localizations. [3] This frequency is higher and may double to triple in HIV-positive subjects. In abdominal tuberculosis, the ileocecal region is most often affected. [3] Other abdominal locations include lymph nodes, peritoneum, liver and spleen. The pancreas is rarely affected by Mycobacterium tuberculosis even in countries with a high prevalence of tuberculosis, with an incidence ranging from 2% to 4.7% according to studies. [6] This rarity may be due to the enzymes produced by the pancreas, which give the pancreatic gland a resistance to invasion by M. tuberculosis. Pancreatic involvement may be primary, by direct ingestion of Mycobacterium, or secondary, due to highly bacilliferous pulmonary lesions by the hematogenous or lymphatic route. Pancreatic tuberculosis affects men and women equally. The median age of reported cases is about 40 years, and children are rarely affected. [3] In our case the age of our patient was 48 years.

The diagnosis of pancreatic tuberculosis is often unrecognized or made late. In most cases, the clinical and radiological aspects are not specific. This disease presents itself on imaging either by:

- -

- A solid form. In this case it should be differentiated from pancreatic adenocarcinoma and focal chronic pancreatitis.

- -

- A cystic form, in which case the differential diagnosis will be mainly with cystic neoplasms of the pancreas (pseudocysts and tumors).

- -

- A mixed form, in which necrotic pancreatic adenocarcinoma should also be considered.

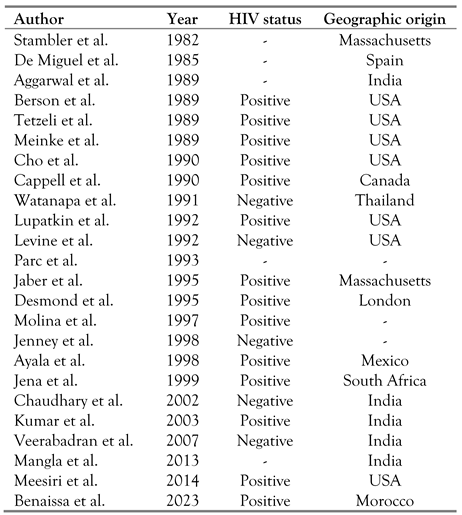

Pancreatic tuberculosis may also manifest itself as an abscess (Table 2), a mass or a cystic lesion of the pancreas. Twenty-one cases of tuberculous abscesses of the pancreas have been reported to date. Tuberculous pancreatic abscesses are more common in HIV-positive patients, probably due to a weaker immunologic response and a higher bacterial load. Our case represented the twenty-second case of tuberculous pancreatic abscess. Chang et al. reported a case in which the patient had a cystic mass in the body of the pancreas with portal and retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy. [6] Other presentations, such as multicystic pancreatic masses, enlarged pancreas, calcifications and peripancreatic nodules have also been described.

Table 2.

Pancreatic tuberculous abscesses and geographic origin [6].

Among abdominal tuberculosis, there is also tuberculous ileitis, which is a rare entity and poses diagnostic difficulties with chronic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and in particular Crohn’s disease. [7] Correct etiological diagnosis of IBD is essential for appropriate treatment, as unnecessary anti-tuberculosis treatment increases the risk of toxicity and multidrug resistance and delays treatment of Crohn’s disease, while steroids and infliximab, commonly used in the treatment of Crohn’s disease, may accelerate the dissemination of tuberculosis and promote intestinal perforation. [7]

Beside abdominal tuberculosis, there is osteoarticular tuberculosis, which accounts for 2–5% of all tuberculosis and 9-20% of extrapulmonary tuberculosis, but also cerebral tuberculosis, which is the second most frequent localization after tuberculous meningitis. It accounts for 10-30% of intracranial expansive lesions in developing countries, compared to 0.2% in some Western countries. [8,9]

Fine needle aspiration (FNA) is the first line diagnostic technique, especially in countries where tuberculosis is endemic, in order to avoid unnecessary exploratory laparotomy. [6] In our patient, such an attitude would have been preferable. The final diagnosis is based on the detection of M. tuberculosis, but this is often difficult because of the paucibacillary nature of extrapulmonary tuberculosis. The Ziehl Neelsen staining technique on smears for acid-fast bacilli (AFB) plays a key role in the diagnosis of tuberculosis, but it has a low sensitivity (10% to 40%) with a good specificity (100%). [10] In our case, microscopic examination with Ziehl Neelsen stain was frankly positive with a scale of 1-10 AFB/field. Conventional culture on solid medium remains the gold standard for positive diagnosis, but the major limitation is its slow growth (3-4 weeks). The advent of rapid molecular tests has shortened these times. Among these methods, the GeneXpert MTB/RIF, a fully automated technique, allows the detection of mycobacteria of the tuberculosis complex and the rpoB gene with high sensitivity and specificity. It provides rapid results. The time to report the results is 2 h. Studies comparing the Xpert MTB/RIF test and standard culture have shown that the sensitivity and specificity of the Xpert MTB/RIF test for extrapulmonary tuberculosis are significantly higher, with respectively 84.9% (vs. 72.92%) and 92.5% (vs. 80.97%), [10] thus allowing for early and appropriate management of extrapulmonary tuberculosis.

Molecular epidemiological studies can provide useful information on the spread of tuberculous bacilli during epidemics and have also helped to study TB transmission dynamics. In addition, molecular typing has highlighted the great differences in pathobiological properties of MTBC species. [1] Thus, identifying the types of MTBC strains responsible for TB in a particular geographic region could help strengthen the TB control program in that particular geographic area, and alert TB program staff to monitor the transmission of particular strains. Digestive tuberculosis is usually dominated by Mycobacterium bovis. This time we report a case of digestive tuberculosis due to the species Mycobacterium tuberculosis which testifies to the efforts made by the health authorities at the national level in the fight against bovine tuberculosis.

Conclusions

The diagnosis of a tuberculous pancreatic abscess may be overlooked because of its rarity and its clinical state simulating a pancreatic tumor, so it should be considered especially in endemic countries like ours.

Author Contributions

E.B. has written the manuscript, A.M. has revised it and M.E. has given final approval to the version to be published. All authors read and approved the final version of the article.

Funding

None to declare.

Conflicts of interest

All authors—none to declare.

Consent

Written informed consent for publication of clinical details was obtained from the patient.

Availability of Data

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

References

- World Health Organization. Tuberculose. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/fr/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tuberculosis (accessed on 11 May 2023).

- Chahboune, M.; Barkaoui, M.; Iderdar, Y.; et al. [Epidemiological profile and diagnostic and evolutionary features of TB patients at the Diagnostic Centre for Tuberculosis and Respiratory Diseases in Settat, Morocco]. Pan Afr Med J. 2022, 42, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Barni, R.; Lahkim, M.; Achour, A. [Abdominal pseudotumoral tuberculosis]. Pan Afr Med J. 2012, 13, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Panic, N.; Maetzel, H.; Bulajic, M.; Radovanovic, M.; Löhr, J.M. Pancreatic tuberculosis: A systematic review of symptoms, diagnosis and treatment. United European Gastroenterol J. 2020, 8, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halse, T.A.; Escuyer, V.E.; Musser, K.A. Evaluation of a single-tube multiplex real-time PCR for differentiation of members of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex in clinical specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 2011, 49, 2562–2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhary, P.; Bhadana, U.; Arora, M.P. Pancreatic tuberculosis. Indian J Surg. 2015, 77, 517–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurzu, S.; Molnar, C.; Contac, A.O.; Fetyko, A.; Jung, I. Tuberculosis terminal ileitis: A forgotten entity mimicking Crohn’s disease. World J Clin Cases 2016, 4, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gbané-Koné, M.; Koné, S.; Ouali, B.; et al. [Osteo articular tuberculosis (Pott disease excluded): About 120 cases in Abidjan]. Pan Afr Med J. 2015, 21, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koffi, P.N.; Ouambi, O.; El Fatemi, N.; El Maaquili, R. [Cerebral tuberculoma a diagnostic challenge: Case study and update]. Pan Afr Med J. 2019, 32, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mechal, Y.; Benaissa, E.; El Mrimar, N.; et al. Evaluation of GeneXpert MTB/RIF system performances in the diagnosis of extrapulmonary tuberculosis. BMC Infect Dis. 2019, 19, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© GERMS 2023.