Abstract

Introduction: One of the most common reasons for pediatric outpatient visits is acute pharyngitis, an upper respiratory tract infection. Bacterial pharyngitis is caused by Group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus (GABHS), also known as Streptococcus pyogenes. This research aimed to assess physicians’ adherence to clinical guidelines for diagnosis, management, and selecting appropriate treatment for children suspected of bacterial pharyngitis. Methods: A retrospective, observational study was conducted by reviewing patient charts for childred aged 3 to 13 years old diagnosed with pharyngitis from June 2019 until December 2019 at the Emergency Department of Palestine Medical Complex (PMC). The Modified Centor score, throat swab collections, and assessment of antimicrobial selection were used to assess the extent of physicians’ adherence to clinical guidelines for appropriate diagnosis and management of pharyngitis. SPSS was used for data analysis. Results: Out of 290 cases diagnosed with acute pharyngitis, 217 patients (74.8%) had a Modified Centor score of ≥2; 126 received antibiotics, and eight had their throat swabbed to confirm the diagnosis; furthermore, 73 patients (25.2%) had a Modified Centor score of <2; 34 of them received antibiotics. Azithromycin was the most commonly prescribed antibiotic (41.3%), followed by amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (38.1%). The frequency of empirical antibiotics prescribing was significantly higher among children with a Centor score >2, older children, and those presenting with fever. Conclusions: Most cases were not appropriately tested to confirm the diagnosis of bacterial pharyngitis and were mostly treated with inappropriate antimicrobial agents such as azithromycin. Nonadherence to clinical guidelines is very evident in this study.

Introduction

One of the most common reasons for pediatric outpatient visits is acute pharyngitis, an upper respiratory tract infection [1]. Viruses contribute to the majority of cases [2]. Adenovirus, respiratory syncytial virus, influenza, parainfluenza, and enteroviruses are common viral causes of pharyngitis [3]. Bacterial pharyngitis is less common and is mainly caused by group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus (GABHS), also known as Streptococcus pyogenes [3]. Throat culture remains the gold standard for diagnosing GABHS pharyngitis. Rapid antigen-detection test (RADT) is another available diagnostic tool [3]. The Infection Disease Society of America (IDSA) recommends swabbing the throat and testing for GABHS pharyngitis by rapid antigen detection test (RADT) and culture should be performed because the clinical features alone do not reliably discriminate between GABHS and viral pharyngitis [4]. Distinguishing between viral and bacterial pharyngitis is essential in guiding therapy. Viral pharyngitis, for instance, requires supportive care only while early recognition of streptococcal pharyngitis and initiating the appropriate antibiotic is crucial in decreasing the risk of possible serious complications such as acute rheumatic fever (ARF) [5].

Yet, antibiotics should not be started empirically even if GABHS pharyngitis is suspected, to prevent inappropriate use of antibiotics, since initiating antibiotics within 9 days of the onset of illness still can prevent ARF [3]. Once GABHS pharyngitis is confirmed, the IDSA recommends that a 10-day course of penicillin be the first-line therapy. In penicillin-allergic patients, alternatives include cephalosporins (preferably first generation), clindamycin, and macrolides [3,4].

Since pharyngitis is a common cause of paediatric outpatient visits, poor adherence to guidelines could lead to a significant unjustified antibiotic overuse. The findings of several previous studies support this concern. In Lithuania, for instance, pharyngitis was one of the three most common indications for prescribing antibiotics in the paediatric population [6]. Moreover, in a study conducted in the United States between 1997 and 2010, the antibiotic prescription rate was 60% [7]. This is a high rate when considering that GABHS infection in school-age children is estimated to account only for 15-30% of cases [3]. This rate is supported by the findings of a study that was conducted in Romania where the rate of positivity for GABHS from a pediatric center was estimated to be 29.9% [8]. In Boston, a retrospective cohort study found that over one-quarter of patients aged 3-18 years were prescribed antibiotics for pharyngitis but did not require antibiotics according to guidelines [9]. Similar findings were seen in another observational retrospective study conducted in Italy, where 56.5% of patients had non-GABHS pharyngitis or unexplained pharyngitis and antibiotics were provided in 63.1% of the cases [10]. In Jordan, researchers found that antibiotics were used to treat 61% of instances of upper respiratory tract infections even though 86% of those patients didn’t require them [11].

Focusing on appropriate antimicrobial use is a healthcare necessity to prevent antimicrobial resistance. Therefore, assessing the usual healthcare providers’ practices in selecting and prescribing antibiotics in the management of pharyngitis is essential to improve prescribing habits and ensure appropriate management since we live in an era where antimicrobial resistance has become a major concern and is thought to become the leading cause of death in a couple of decades [12]. Therefore, this research aimed to assess physicians’ adherence to clinical guidelines for diagnosis, management, and selecting appropriate treatment for children aged 3 to 13 years suspected of bacterial pharyngitis infection in a central governmental hospital in Palestine.

Methods

This retrospective, observational study was conducted at the Bahrain Paediatrics Hospital in the Palestine Medical Complex (PMC), a central governmental hospital in Ramallah, Palestine. This 45-bed hospital provides several services for children aged 1 day to 13 years. Pharyngitis cases that were encountered from June 2019 to December 2019 were collected. Exclusion criteria included patients who had suspicions of lower respiratory tract infections or other sources of infections (e.g., urinary tract infections), patients who were on antibiotics at the time of presentation, having other comorbidities (e.g., congenital heart disease), patients to be admitted and those who were discharged against medical advice. Patients less than 3 years old were also excluded because the presentation of GABHS is variable and appropriate management is less defined among this age category [4]. Only cases that were documented in the detailed physician notes as pharyngitis were included. More than 35,000 cases were registered at the emergency department during the study period, of which 537 cases had pharyngitis. After applying the exclusion criteria, a total of 290 cases were included and reviewed.

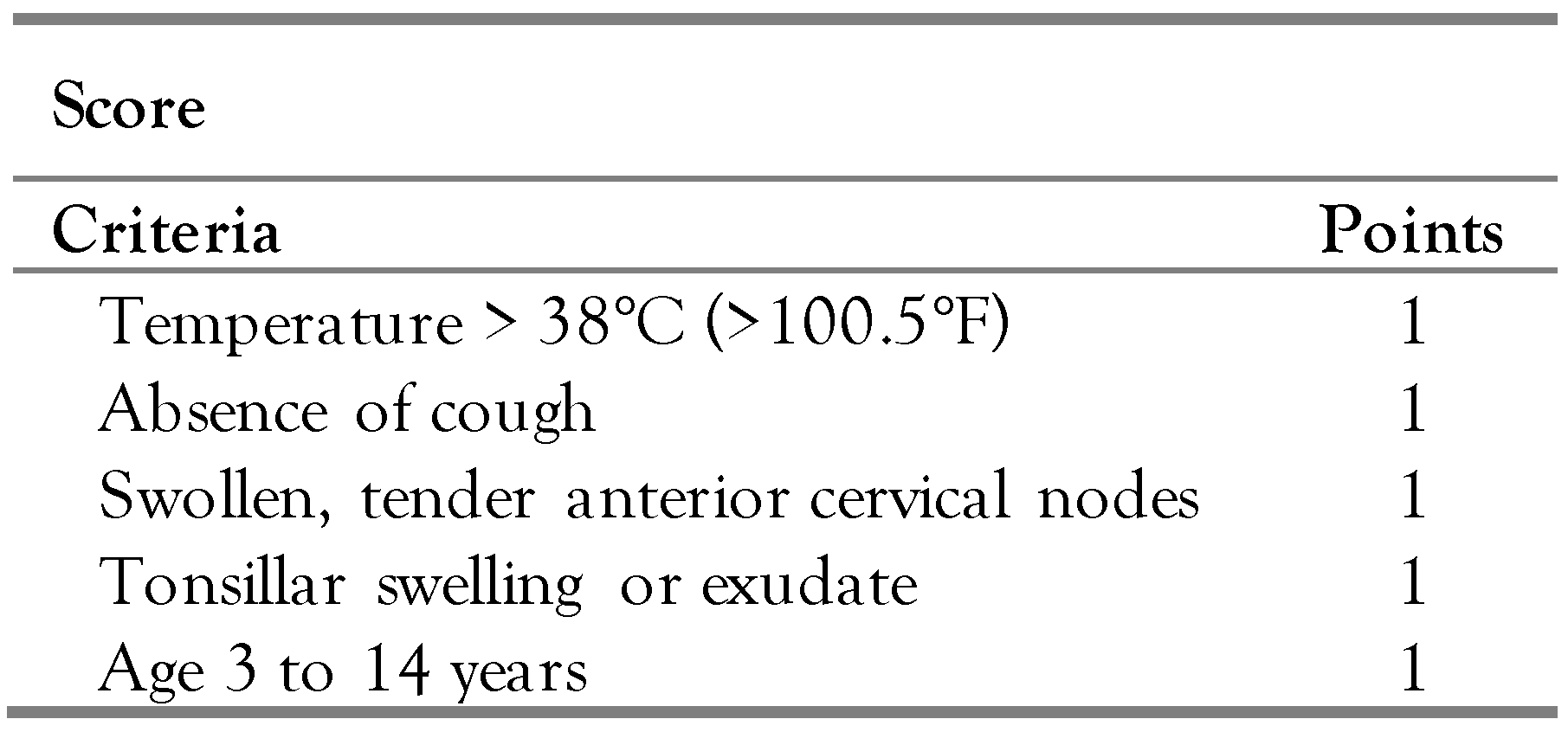

Two teams of a total of four researchers were responsible for data collection. The following data were extracted from each file: demographics (patient file number, gender, age, date of visit, and presence of penicillin allergy), presenting symptoms (fever, cough, tonsillar swelling or exudate, and swollen, tender anterior cervical nodes), and management (throat swab taken or not, antibiotic prescribed or not, and the type of antibiotic). Patient file numbers were kept private and used only to access the mentioned data. The Modified Centor score (or McIsaac score) was calculated for each patient using the indicators mentioned in Table 1 [13]. Microsoft Excel was used to arrange data, and the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) was used for data analysis.

Table 1.

Modified Centor (or McIssac) Score [13].

Calculation of the Modified Centor score (McIsaac score): The McIsaac score was used in this study as a clinical score to assess the likelihood of having GABHS pharyngitis. The clinical importance of this score stems from the fact that it has a sensitivity up to 96.9% compared to physician care, which has a sensitivity of 70.6%. Moreover, specificity is similar compared to physician care. This score assigns points to certain clinical features to identify patients at higher risk for bacterial pharyngitis as shown in Table 1. Any patient scoring two points or more is eligible for throat swab/RADT [14]. In our study, if a patient’s record indicated a fever of more than 38 °C degrees, we deemed them to have a fever. In most cases, fever was unspecified, and the grade was not mentioned; therefore, the patient was not assigned a point. Regarding the other parameters, patients scored the points according to the data documented in their files.

Results

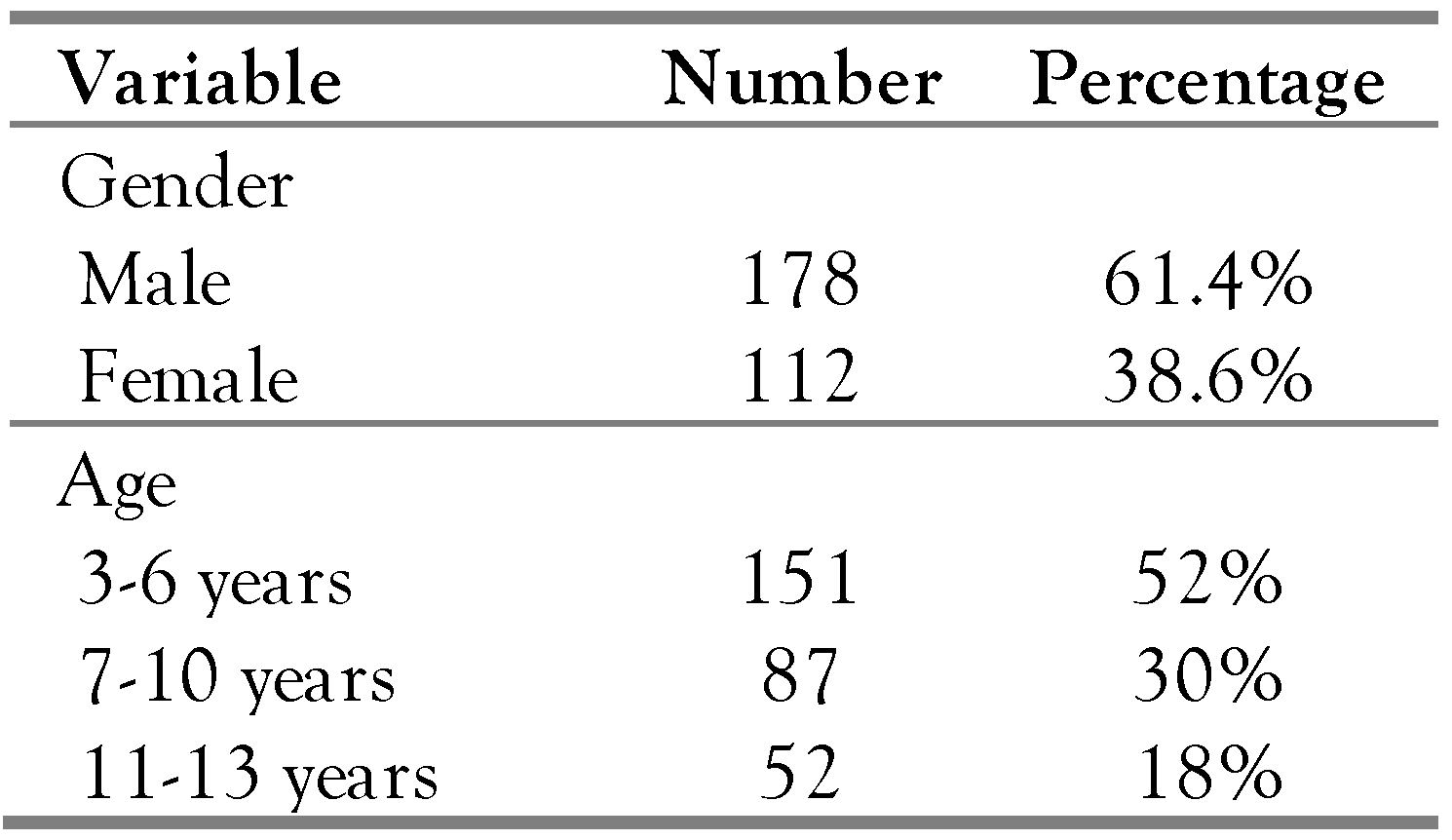

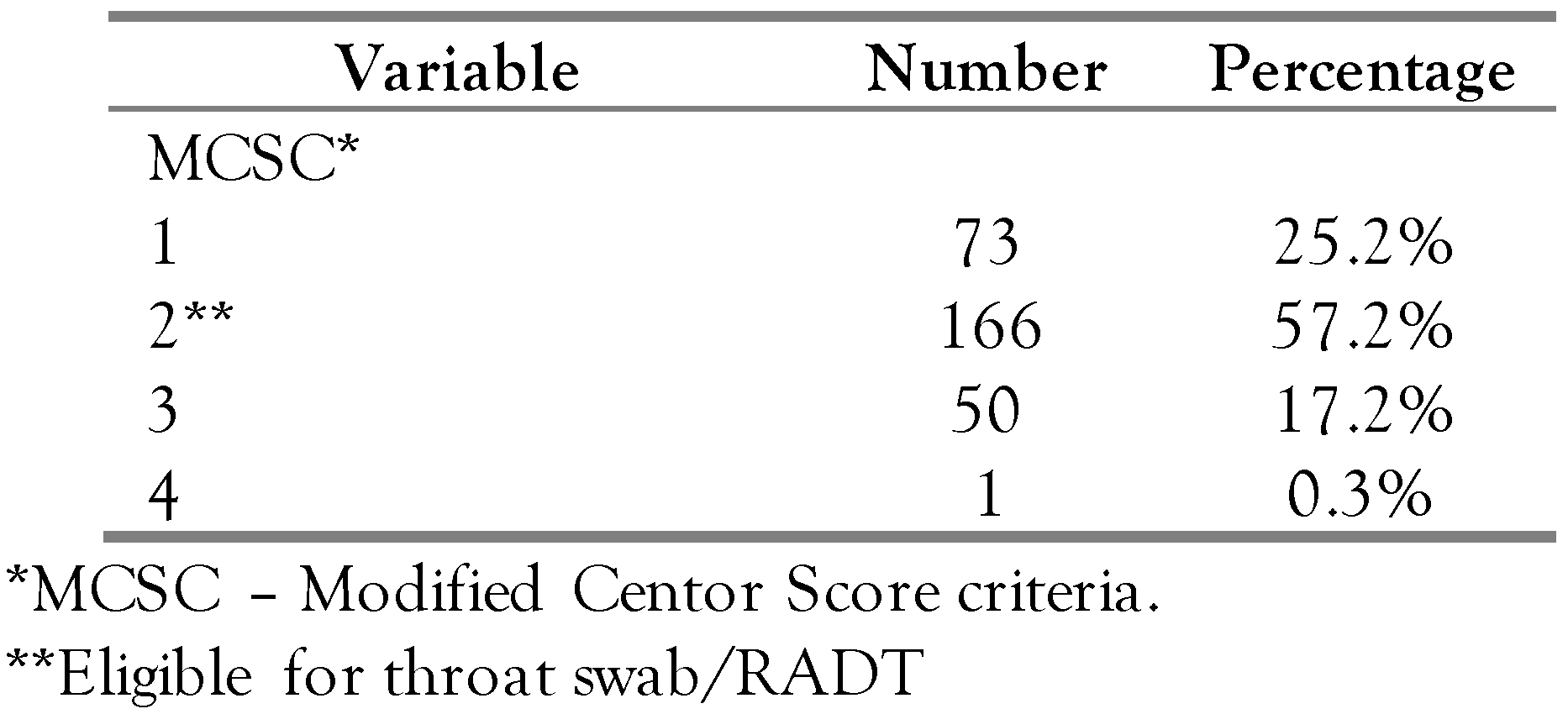

A total of 290 cases were included in this study. The majority were males (61.4%) and in the age range of 3-6 years (52%)—Table 2. Around one-third of the study sample (38%, N = 180) reported fever upon Emergency department visits. The majority of the cases did not complain of swollen cervical nodes (97%, N = 282) or swelling tonsils (97.6%, N = 283). Half of the study sample reported having a cough (N = 145). More than two-thirds of the cases (75%, N = 217) scored two or more on the Modified Centor score criteria (N = 217) (Table 3), of which 58% received antibiotics (N = 126); among the 73 cases with a Modified Centor score of <2, 34 (46.6%) received antibiotics, and no swab was taken for any of them.

Table 2.

Demographics of cases (N = 290).

Table 3.

Modified Centor Score (MSC) results.

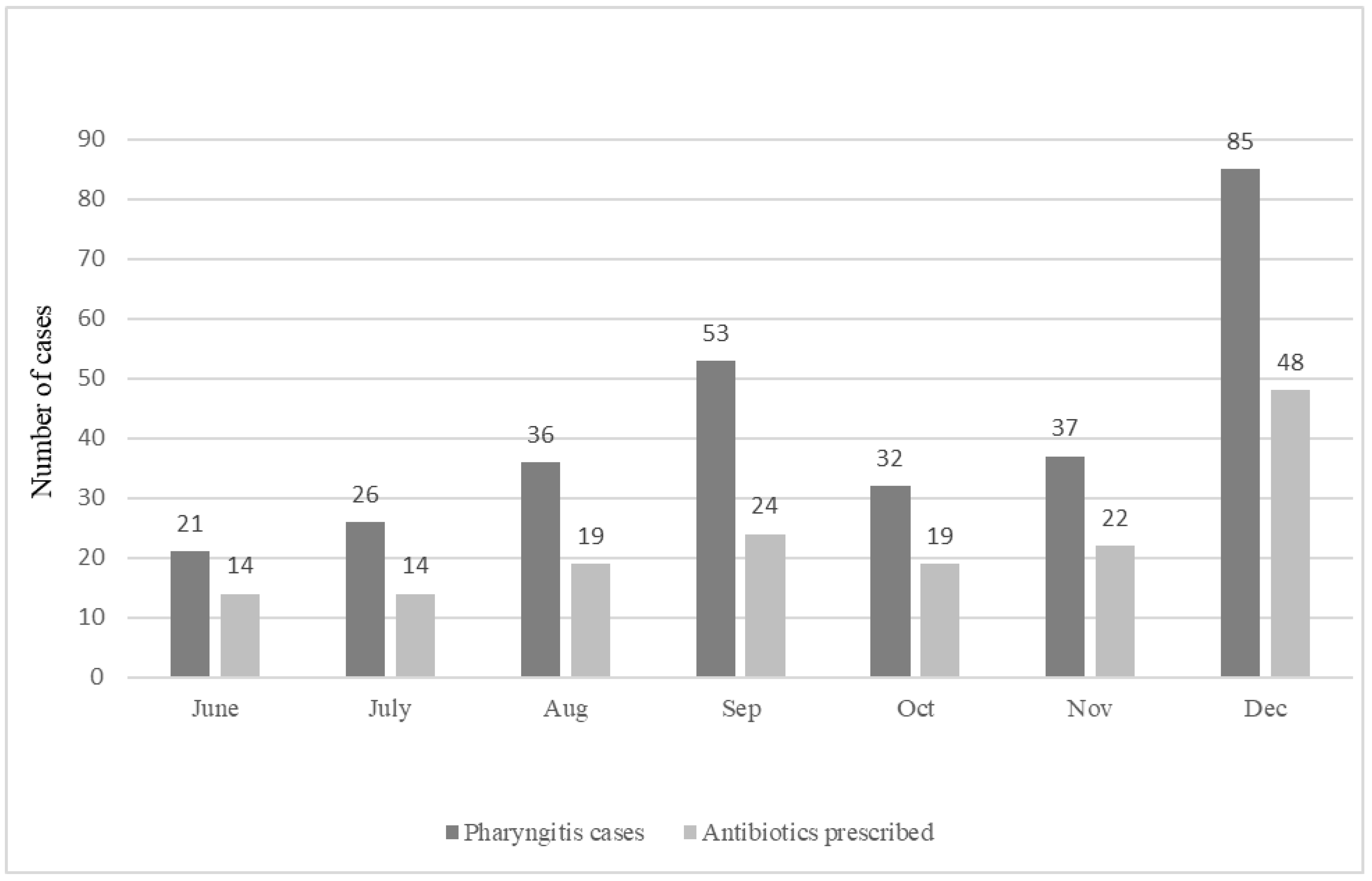

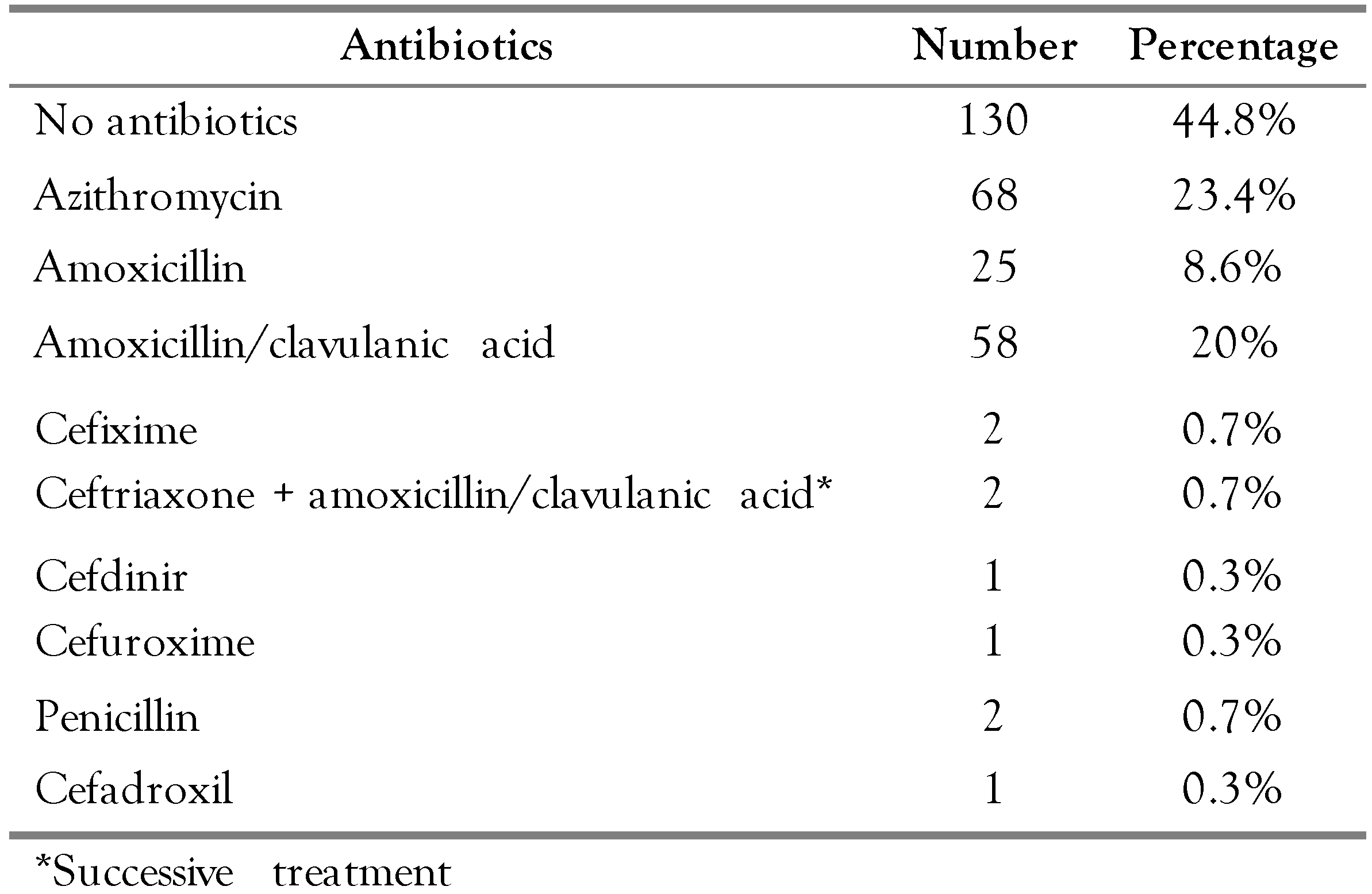

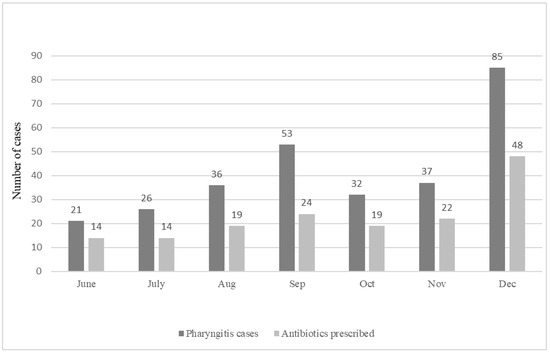

More than half the study sample (55.2%, N = 160) were prescribed antibiotics. Azithromycin was the most commonly prescribed antibiotic (23.4%, N = 68), followed by amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (20%, N = 58)—Table 4. Eight patients underwent throat swabbing (2.8%), all of which had a Centor score of more than two, and 6 of them empirically received antibiotics. Out of the 160 cases that received antibiotics, only two patients had a documented penicillin allergy and were given azithromycin accordingly. Over the seven months, pharyngitis visits were most common in December, followed by September, with the least number of cases in June (Figure 1).

Table 4.

Prescribed antibiotics (N = 290).

Figure 1.

Antibiotics prescribed over the selected months.

The results show a significant correlation between Modified Centor Score value and antibiotic prescribing (r = 0.154, p = 0.009). This indicates that the chance of receiving antibiotics was higher for those presenting with more signs and symptoms. Fever was also significantly associated with antibiotic prescription (r = 0.204, p<0.001). Furthermore, age was an important variable as more antibiotics were prescribed for older children compared to younger children (r = 0.189, p = 0.001). Lastly, the rate of antibiotic prescribing was not altered by the time of the year at which a case was seen (p = 0.520).

Discussion

The improper management of pharyngitis and the lack of adherence to clinical guidelines is very evident in this study, as shown in the results. Around three-quarters of the cases had a Modified Centor score of ≥2. According to clinical guidelines, a Modified Centor score of ≥2 necessitates testing for GABHS pharyngitis using a throat swab or RADT, as the likelihood for GABHS pharyngitis in patients is estimated to be 20.5% and increases as the score increases [15]. Antibiotic therapy should be started once GABHS pharyngitis is documented by RADT or throat culture, except for cases identified as chronic GABHS carriers since a positive swab is not indicative of disease in all cases [16,17]. Throat swabs were not used routinely in the studied setting, which led to the expected overprescribing of antibiotics. Only eight throat cultures were obtained, yet 160 patients (55%) received antibiotics empirically, without any confirmatory test for the presence of bacterial pharyngitis. This finding is alarming and would lead to significant overuse of antibiotics. Throat swabs are an essential part of pharyngitis management, and their use is recommended strongly in various clinical guidelines to properly guide therapy and decrease unnecessary antibiotics use [18]. Previous studies showed that only 25% of patients with a Centor score of ≥3 had a documented positive throat culture for GABHS pharyngitis [19]. Furthermore, antibiotics were ordered for patients with a Centor score <2 without ordering a throat swab to confirm the diagnosis or offering the patient an observation period to monitor symptoms severity while providing symptomatic treatment, which represents a major deviation from clinical guidelines.

In the study, the Centor score influences the practitioner’s decision on prescribing antimicrobial agents. The higher the Centor score, the higher the chance of antibiotic prescribing (r = 0.154, p = 0.009), and the more signs and symptoms the child experience, the more likely physicians will attribute it to bacterial causes and recommend antibacterial therapy. This type of practice could be acceptable if a throat swab preceded the empirical therapy to either confirm a diagnosis or change the course of therapy. However, there might be certain alarming information demanding and justifying empirical antibiotics before obtaining swab results. These include limited conditions where a patient has a high suspicion of GABHS pharyngitis, i.e., having a diagnosis of scarlet fever, an asymptomatic child having a household member with documented GABHS infection, or in cases where the patient (or a family member) has a history of ARF [3]. Throat swab has a vital role in confirming the specific diagnosis, which cannot be made relying only on clinical features. Therefore, the diagnosis should always be confirmed using throat culture or RADT prior to antibiotic initiation [3]. Confirming the diagnosis is a safe practice even when MCS is >2 (i.e., GABHS is suspected) since starting antibiotics in bacterial pharyngitis within 9 days of symptom onset can still prevent the development of complications (mainly rheumatic fever) [3,5].

In this study, fever was the most common complaint occurring in one-third of the study sample and was significantly associated with antibiotics prescribing. This finding agrees with other studies where the fever was the most common clinical feature in confirmed bacterial cases [19]. However, the symptoms of bacterial pharyngitis overlap with those of viral pharyngitis, and decisions made solely based on the presence of fever might lead to antibiotic overuse [20]. The results show an inappropriate use of antimicrobial agents either by indication or by selection. Antimicrobial agents were prescribed without a definite diagnosis to confirm bacterial pharyngitis as stated previously, furthermore assuming confirmed diagnosis, the inappropriate selection of an antimicrobial agent was alarming. For example, azithromycin was prescribed for 68 patients (41%), whereas only two patients had a documented penicillin allergy (Table 4). Oral penicillin V or amoxicillin are recommended in treating GABHS pharyngitis and should be selected as first-line agents for patients without penicillin allergies [21]. These agents have a narrow spectrum of activity, few side effects, and reasonable cost [4]. Macrolides and cephalosporins can be alternatives for type I and II penicillin allergies, respectively [3]. However, macrolide use in pharyngitis was reported to be substantially increasing against the recommendations of treatment guidelines [7]. This finding is similar to previous findings involving paediatric patients [7]. In a study that was conducted in Canada, for example, antibiotics were prescribed inappropriately in 85% of cases in preschool children having pharyngitis [10]. Another study from the United States showed that over a quarter of children received antibiotics for pharyngitis, although these were not indicated according to treatment guidelines [9]. Physicians are advised to adhere to clinical guidelines regarding antibiotic selection as there is no evidence that macrolides are clinically superior to penicillin in the absence of penicillin allergy [22]. This indicates that antibiotic overprescribing is a global issue that the healthcare sector is facing, not only in our studied setting.

Pharyngitis cases can be seen anytime throughout the year, but peak seasons depend on the causative agent, generally during winter, while pharyngitis cases due to viral causes are usually seen in the summer [3,23]. These infection characteristics are very evident in the study sample as the highest incidence was in December (Figure 1) and a gradual increase of visits was seen from June to September, as shown in Chart 1. However, the seasonal peak of the infections did not alter the healthcare providers’ course of action in prescribing antibiotics, as the rate of antibiotic prescribing was not altered by the time of the year at which patients were seen (p = 0.520). Another interesting finding is that the antibiotic prescribing rate was significantly higher in older children compared to younger children, possibly out of fear of developing serious complications such as ARF. Overall, the results of this study show a wide gap in clinical guidelines and usual practice in the management of pharyngitis.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Strengths: The study was conducted in a central governmental hospital where most of the nearby population receives medical help. The hospital hosts pediatric residency program, so the study reflects the practice of current and future pediatricians.

Limitations: Only seven months were included since ICD-10 codes were not correctly used and case collection through electronic search was not feasible. Data were collected manually through reviewing all ER cases, and it is therefore subjected to human errors.

Conclusions

Nonadherence to clinical guidelines is very evident and alarming in this study. Therefore, adapting clinical protocols and establishing antimicrobial stewardship programs to include physicians and clinical pharmacists to monitor, recommend, restrict, implement protocols and educate healthcare providers on the appropriate use of antimicrobial agents is warranted in the Palestinian health institutions. Furthermore, adherence to clinical guidelines in confirming the diagnosis and selecting the appropriate antimicrobial if indicated in the management of pharyngitis is warranted in preventing antimicrobial resistance, improving patient outcomes, preventing complications, and decreasing healthcare costs.

Author Contributions

SN, HS and HF were responsible for the study design. SN planned and supervised the project. HS, HF, RA, MM collected data. HS, HF, RA, MM and SN wrote the first draft equally. HF, HS, SN and MD did data analysis. SN, HS and HF interpreted the data. ADA and MD reviewed and edited the article. SN and HN critically revised the first draft and made appropriate amendments. HN submitted the article to the journal. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

None to declare.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Research Committee of the Faculty of Graduate Studies, Health Sciences Department, Arab American University approved the study. All methods were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the corresponding author on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to express their heartfelt gratitude to all health teams at Palestine Medical Complex for their support.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors—none to declare.

References

- Gerber, M.A. Pharyngitis. In Principles and Practice of Pediatric Infectious Disease, 3rd ed.; Long, S.S., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.K.; Park, C.S.; Kim, J.W.; et al. Guidelines for the antibiotic use in adults with acute upper respiratory tract infections. Infect Chemother 2017, 49, 326–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanz, R.R. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics, 20th ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Shulman, S.T.; Bisno, A.L.; Clegg, H.W.; et al. Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of group A streptococcal pharyngitis: 2012 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2012, 55, 1279–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pichichero, M. Treatment and prevention of streptococcal pharyngitis in adults and children. In UpToDate; Post, T.W., Ed.; UpToDate: Waltham, MA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Karinauske, E.; Kasciuskeviciute, S.; Morkuniene, V.; Garuoliene, K.; Kadusevicius, E. Antibiotic prescribing trends in a pediatric population in Lithuania in 2003-2012: Observational study. Medicine 2019, 98, e17220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dooling, K.L.; Shapiro, D.J.; Van Beneden, C.; Hersh, A.L.; Hicks, L.A. Overprescribing and inappropriate antibiotic selection for children with pharyngitis in the United States, 1997-2010. JAMA Pediatr 2014, 168, 1073–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miron, V.D.; Bar, G.; Filimon, C.; Gaidamut, V.A.; Craiu, M. Streptococcal pharyngitis in children: A tertiary pediatric hospital in Bucharest, Romania. J Glob Infect Dis 2021, 13, 154–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brennan-Krohn, T.; Ozonoff, A.; Sandora, T.J. Adherence to guidelines for testing and treatment of children with pharyngitis: A retrospective study. BMC Pediatr 2018, 18, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbieri, E.; Donà, D.; Cantarutti, A.; et al. Antibiotic prescriptions in acute otitis media and pharyngitis in Italian pediatric outpatients. Ital J Pediatr 2019, 45, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Omari, M.; Yahia, G.; Khader, Y.; Batieha, A.; Dauod, A.S. Antibiotics in upper respiratory tract infections: Appropriateness of the practice in Jordan. Jordan Med J 2011, 44, 413–419. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. New Report Calls for Urgent Action to Avert Antimicrobial Resistance Crisis. 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/29-04-2019-new-report-calls-for-urgent-action-to-avert-antimicrobial-resistance-crisis (accessed on 27 February 2023).

- Fine, A.M.; Nizet, V.; Mandl, K.D. Large-scale validation of the centor and mcisaac scores to predict group A streptococcal pharyngitis. Arch Intern Med 2012, 172, 847–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McIsaac, W.J.; Kellner, J.D.; Aufricht, P.; Vanjaka, A.; Low, D.E. Empirical validation of guidelines for the management of pharyngitis in children and adults. JAMA 2004, 291, 1587–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- University of Saskatchewan. Pharyngitis: Management Considerations. 2019. Available online: https://www.rxfiles.ca/rxfiles/uploads/documents/ABX-Pharyngitis.pdf (accessed on 27 February 2023).

- College of Registered Nurses of Saskatchewan. Pharyngitis: Adult & Pediatric. Ears, Eyes, Nose, Throat and Mouth Clinical Decision Tool for RNs with Authorized Practice [RN(AAP)s]. 2022. Available online: https://www.crns.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Pharyngitis-Adult-Pediatric-CDT-2022.pdf (accessed on 27 February 2023).

- Rick, A.M.; Zaheer, H.A.; Martin, J.M. Clinical features of group A streptococcus in children with pharyngitis: Carriers versus acute infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2020, 39, 483–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunnarsson, R.; Ebell, M.H.; Wächtler, H.; et al. Association between guidelines and medical practitioners’ perception of best management for patients attending with an apparently uncomplicated acute sore throat: A cross-sectional survey in five countries. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e037884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balasubramanian, S.; Amperayani, S.; Dhanalakshmi, K.; Senthilnathan, S.; Chandramohan, V. Rapid antigen diagnostic testing for the diagnosis of group A beta-haemolytic streptococci pharyngitis. Natl Med J India 2018, 31, 8–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustafa, Z.; Ghaffari, M. Diagnostic methods, clinical guidelines, and antibiotic treatment for group A streptococcal pharyngitis: A narrative review. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2020, 10, 563627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flood, S.; Woods, J. Strep Pharyngitis in Children: Review of the 2012 IDSA Guidelines. Available online: https://www.aliem.com/strep-pharyngitis-pediatric-idsa-2012-guidelines/ (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Satti, A.M.; Alkenany, H.A.; Alsafi, M.Y.; Hussain, M.A. Efficacy of macrolides versus penicillins against streptococcal pharyngitis: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Inf J Pharma Sci 2016, 6, 1698–1704. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, J.C.; Nizet, V. Pharyngitis. In Principles and Practice of Pediatric Infectious Disease, 5th ed.; Long, S.S., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 202–208.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© GERMS 2023.