Introduction

Viral infections are responsible for about 20% of all cancers. In fact, several viruses like Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) or the human herpesvirus 8 (HHV8) are classified as oncogenic while the presence of others viruses has been reported in several cancers [

1]. Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) is a herpesvirus that infects at least half of the population in developed countries and almost everyone in developing ones. In the latent state, the host remains asymptomatic [

2]. The “viral reactivation” in immuno-compromised patients is often associated with immune suppression, chronic inflammation and cancer. In fact, several HCMV proteins (IE1–72, IE-1/IE-2 and pp65) are implicated in apoptosis inhibition, cell proliferation, stem cells induction, immune escape, metastasis, and angiogenesis, which give an oncomodulatory property to the virus. Moreover, HCMV was detected in several cancers such as primary intracerebral tumors, colorectal, breast cancer and mainly gliomas [

2,

3].

Gliomas are a highly heterogeneous group. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), they are classified in four prognostic grades on the basis of degree of anaplasia and in different histological subtypes. Gliomas are generally classified in astrocytomas, oligodendrogliomas and ependymomas. Glioblastomas (WHO grade IV) frequently occur at the level of the white matter of the cerebral hemispheres and are unfortunately the most frequent diffuse astrocytomas [

4]. Before the first detection of cytomegalovirus by Cobbs [

2] and even afterwards, research on gliomas tended to focus on genetic mutations. In fact, histology and grading are not sufficient to fully characterize a glioma. In 2016, the WHO incorporated some molecular characteristics in the CNS classification. In fact, oligodendrogliomas require some molecular changes such as 1p/19q co-deletion, mutations or fusions in key genes located in 1p and also in the promoter of telomerase reverse transcriptase (

TERT) [

4]; while astrocytomas are characterized by additional mutations that occur in tumor protein 53 (

TP53) (80% of cases) and in alpha thalassemia/mental retardation syndrome X-linked gene (

ATRX) [

4].

These genomic alterations are preceded by changes in microenvironment and particular interest is shown in isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH)1/2 mutations. Those mutations are found early and frequently (50–80%) in low-grade glioma patients, as well as in a small fraction of glioblastoma patients (2–20%), especially in those with secondary glioblastomas. Mutations in the

IDH1 and

IDH2 genes are somatic and invariably heterozygous. They can lead to genetic instability [

4].

It also was shown that HCMV induces immune suppression, chronic inflammation, cell proliferation and apoptosis inhibition. However, its involvement in gliomas and other brain tumors types remains controversial. A recent study has shown that regardless of the treatment, the virus is associated with poor prognosis in glioma patients especially in high-grades gliomas (HGGs) [

5]. Also, HCMV reactivation is frequently observed during radio (chemo) therapy in patients with brain tumors and causes encephalopathy but this data remains insufficient to establish an association between the virus and the patient’s prognosis [

6]. In contrast, it is well established that IDH mutation is a better prognosis factor compared to the wild-type IDH in gliomas, making this gene the most important prognostic marker [

4]. However, most studies are interested in the association between HCMV and glioma according to histological classification and the involvement of this virus in gliomas depending on IDH status is not largely studied. Thus, this study aimed to verify the association between HCMV and gliomas considering the IDH subgroup in a Moroccan population and to verify its possible impact on patients’ survival.

Discussion

Primary malignant brain tumors are rare but represent a serious health burden due to their poor outcome. The presence of HCMV in these tumors is largely discussed and its prognostic value was reported in several studies. However, only few studies investigated the association between HCMV and gliomas according to IDH status. This study is the first one conducted in Morocco to determine the prevalence of HCMV in gliomas and its association with IDH status and patients’ survival.

Several studies were interested in the detection of HCMV DNA and proteins in gliomas of different grades of malignancy. Thus, the virus was detected at different rates ranging from 0 to 90% [

2,

9] and this difference was explained by the tumor’s sample size, diagnosis techniques and geographical area [

2,

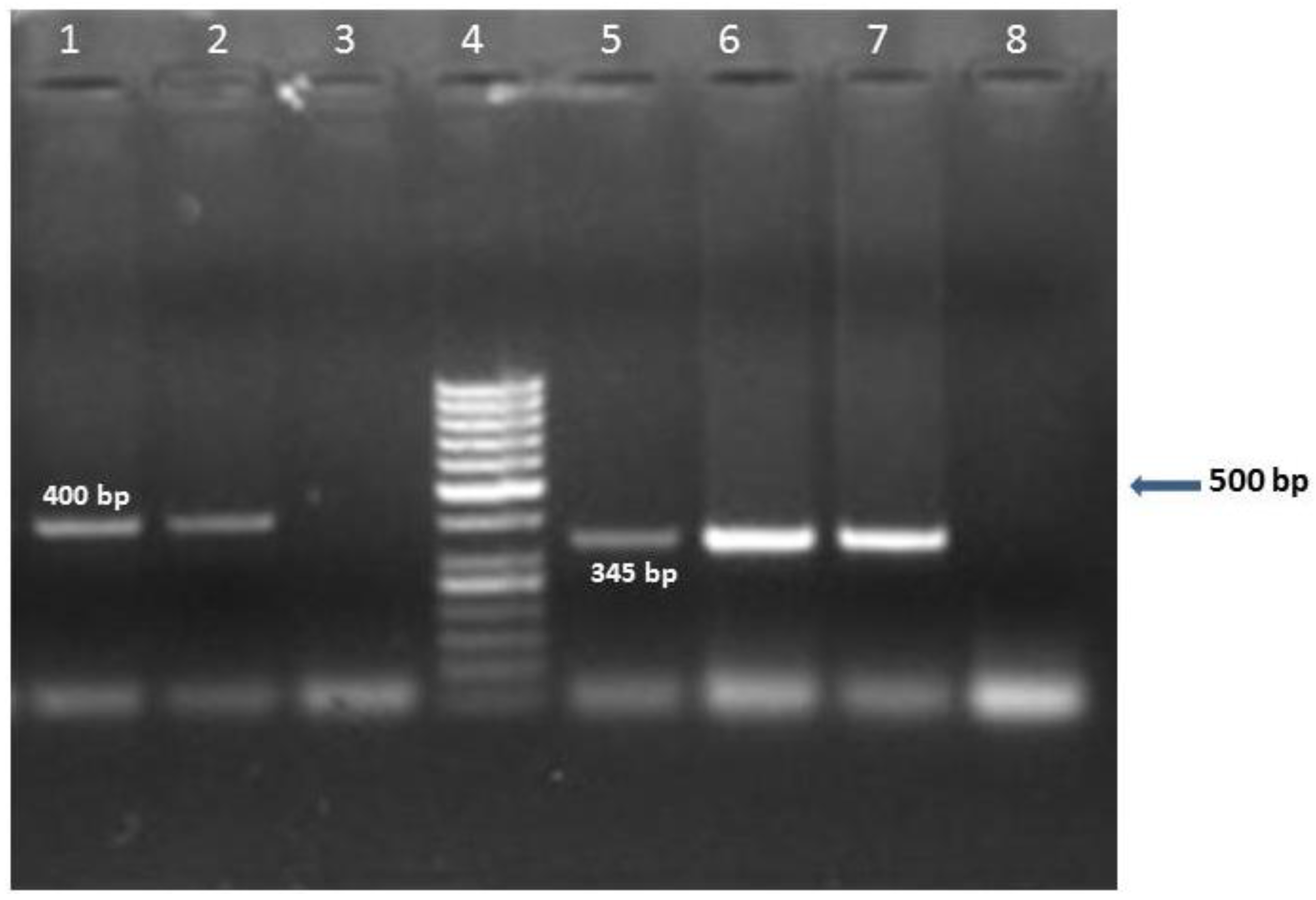

9]. In fact, a great variability in the level of viral detection were observed this last decade with the use of different methodological approaches (IHC, ISH and PCR) and different sampling techniques (fresh or embedded paraffin tissues). In our study, nPCR was used to detect HCMV DNA extracted from fresh-frozen tissues. The primers used target the major immediate-early (IE) gene, which is an important indicator of viral reactivation, and a variety of its products are implicated in immune escape, apoptosis inhibition, cell proliferation and angiogenesis as well as in viral replication [

10]. The detection of IE gene using nPCR is largely used [

8,

11] and has shown large sensitivity when used in fresh-frozen tumor samples. According to Bhattacharjee et al. (2012), this method allows detection of low levels of DNA beyond the limit of real time PCR and helps prevent false positives detection [

8].

The nPCR results show that HCMV DNA is present exclusively in tumor group patients. This result may corroborate the hypothesis, which suggests that the tumor microenvironment is favorable to the reactivation of the virus and that the oncomodulatory properties of HCMV could be beneficial to the tumor evolution [

10]. So, to verify this hypothesis, it will be necessary to verify the serological status of HCMV in each studied population, ethnic groups or geographical area. In fact, if HCMV is considered as oncomodulator, its rate in cancer cases will depend on its prevalence in the concerned geographical area. Unfortunately, there is a lack of data on HCMV seroprevalence in several countries notably in Morocco rendering its actual incidence undetermined. Therefore, such association must be studied in the future.

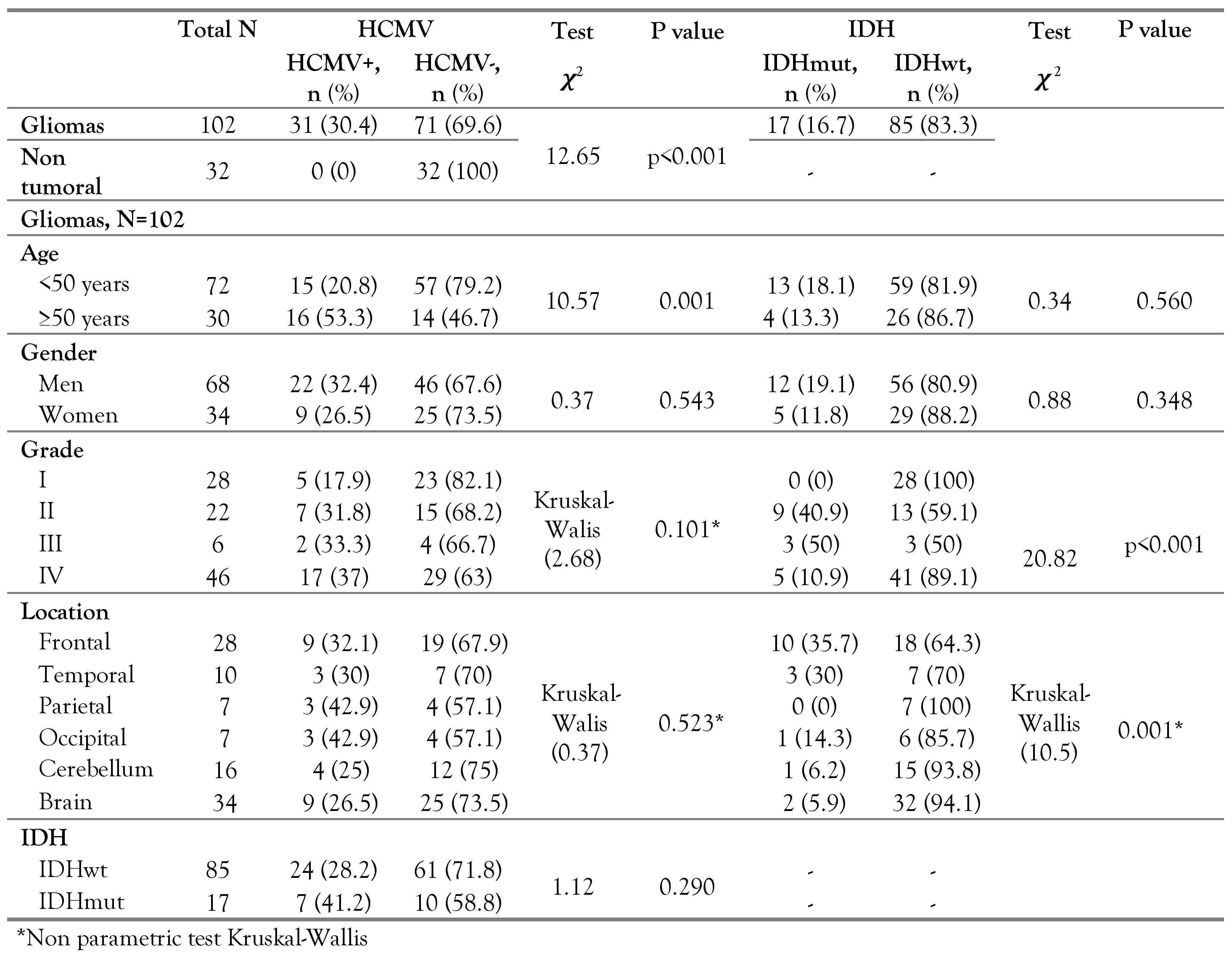

The HCMV was detected with a rate of 30.4% (31/102) in gliomas (independently of their histology) (p<0.001). This rate is different from those detected in England (94%) [

8], in Iran (70.1%) [

12] and in China (28.6–43.6%) [

10]. No significant association was obtained between HCMV and gender even if the infection rate appears to be higher in men than in women. However, a significant association was obtained between HCMV and the age of glioma patients (p=0.001) with higher prevalence in older population (>50 years). In fact, in the elderly, HCMV can play a role in the weakness of immunity functions [

13] and the progression of immuno-senescence can be responsible for increasing the rate of viral infections recurrence and the risk of mortality [

13]. Considering the opportunistic nature of HCMV infection, our result can corroborate the hypothesis of HCMV reactivation following systematic or focal immunosuppression associated to gliomas.

In glioma patients, HCMV tends to be more prevalent in grade IV than in other grades (p=0.1). Even if this difference is not statistically significant, this result can corroborate those obtained in other geographical areas [

10,

12]. Thus, the high rate of HCMV detected in glioblastomas can be related to the favorable conditions of reactivation related to this tumor characteristics (immune-suppressed phenotype, extensive mitosis, vascularity and necrosis, profound infiltrating cells, and secretion of growth factors and inflammatory cytokines) which are also partially present in anaplastic gliomas [

12]. The fact that reactivation occurs only in the tumor microenvironment and not in the surrounding healthy tissue [

10] can confirm that the conditions created by the tumor and particularly glioblastoma promote the reactivation of the virus. Thereafter, HCMV plays a role in oncomodulation and in tumor progression. To explain the rates of this virus in different glioma grades, the serological HCMV status is an additional important factor that could be considered. Evidently, the rate of HCMV detection (activated infection) depends on the rate of latent infection and, in some way, on the rate of seropositive patients. Unfortunately, this data is not available.

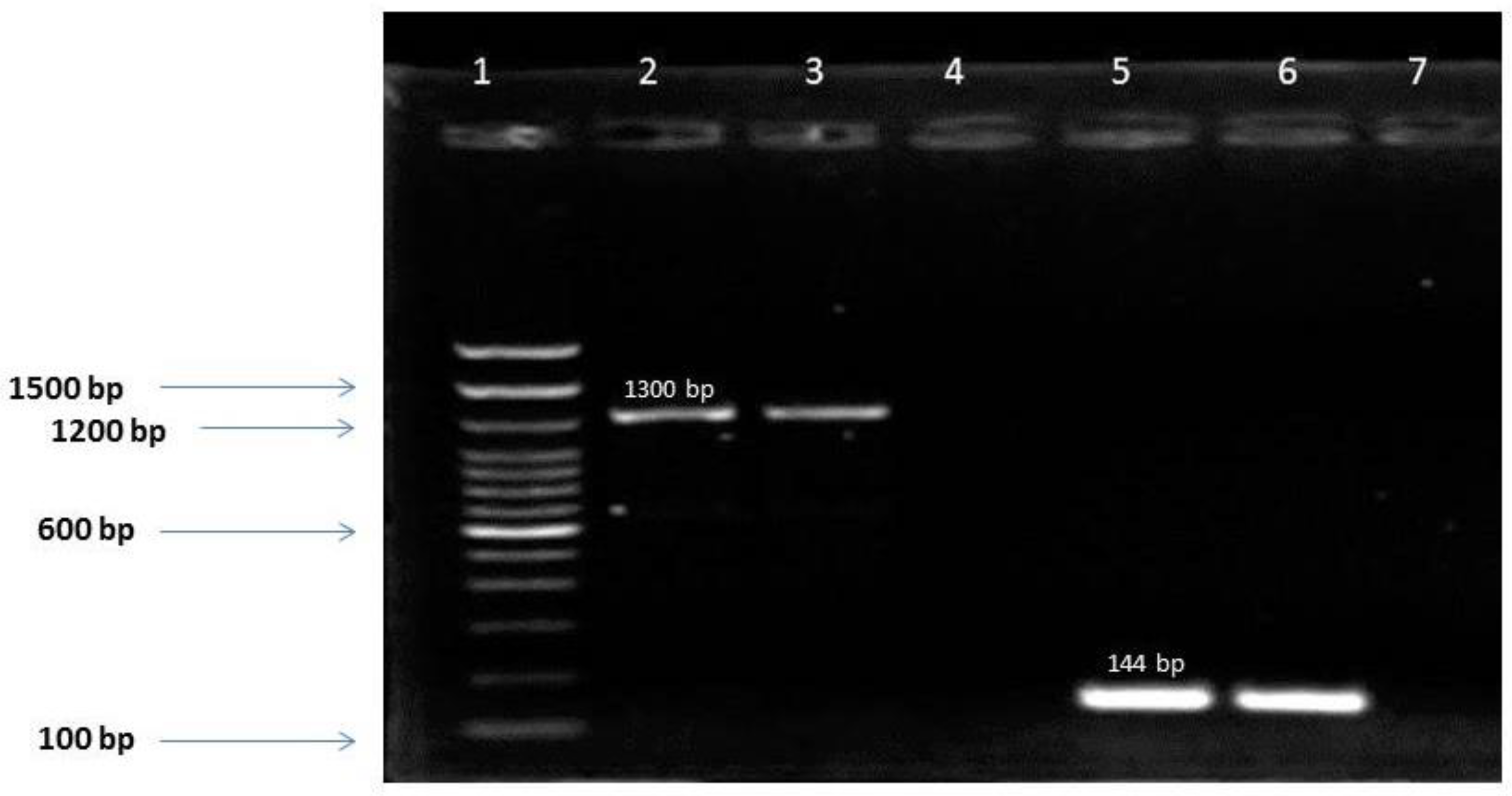

In this study, the IDH1 (R132) mutation was detected in 16.7% of gliomas and none of R100 IDH1 or R172 IDH2 was found. This result was not surprising since mutations R100 IDH1 and R172 IDH2 were rare in gliomas [

14]. The prevalence of the IDH mutations varies according to glioma grade. In fact, Yao et al. showed that IDH mutations were associated with a less aggressive glioma phenotype compared to the wild type and with a less invasive characteristic of low grade gliomas [

15]. This was confirmed by our results since IDH1 mutation was detected in 40.9%, 50% and 10.9% of grade II, III and IV respectively (p<0.001). The low mutation rate detected in glioblastomas was comparable to that obtained in other studies notably in the USA (12%) [

16]. It also implies a predominance of primary glioblastomas in our cohort (IDHwt: 41/46).

The IDH mutation was not associated with patients’ age even if it was slightly more predominant in younger people (<50 years) (18.1% vs. 13.3% in >50 years). This tendency was reported in others studies [

12,

17] and can be explained by the frequent occurrence of IDH mutation in grade II-III gliomas (which are predominant in young patients) compared to primary glioblastomas (which are more frequent at old age) [

17]. Also, IDH mutations are more frequent in males, which is concordant with the results of most studies [

12,

17]. This trend has not yet been explained and the implication of hormonal and/or metabolic factors deserves to be explored.

More than half of IDH1 mutations (10/17) were obtained in patients with frontal lobe tumors (p=0.004), which was in accordance with US results [

17]. In fact, the IDH mutated gliomas were predominantly located in a single lobe, such as the frontal lobe and temporal lobe, where tumors can be removed simply [

15].

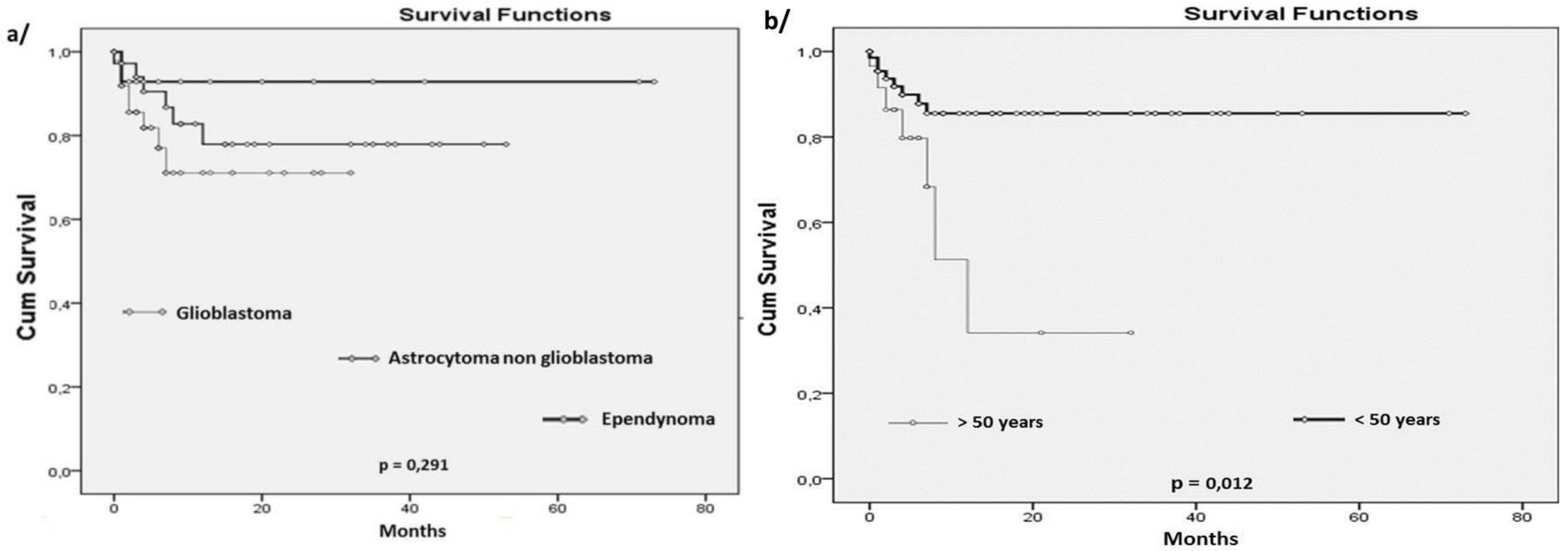

OS in glioma patients were determined according to several variables: age, tumor histology, IDH status and HCMV infection. Several studies [

18,

19] reported that survival was associated with the patient’s age in gliomas. The obtained results confirm this data and show that mOS in older patients (>50 years) was 26.4 months compared to 63.3 months for the younger patients (<50 years) (p=0.012). This difference can be explained by the prevalence of glioblastoma in the older population. In fact, patients with glioblastomas had the lowest mOS (23.8 months) compared to those with others astrocytoma types (42.7 months). This result (despite its lack of statistical significance (p=0.291)) was not surprising and is in accordance with those reported in Sweden and the USA (with survival averages of 15.7 and 36 months for glioblastomas and others astrocytomas, respectively) [

18,

20]. In fact, grade II-III astrocytomas are less aggressive and probably show some molecular characteristics (as IDH mutation) that can be associated with relatively good prognosis; they also occur in younger age and in patients with more active immune response, that will probably have an impact on the tumor evolution and patients’ OS.

Moreover, several studies show significant association between OS and IDH status with a better prognosis in IDH mutated patients. In our study, the OS of glioma patients was not significantly associated with IDH mutation even if a difference in mOS between IDHmut (44.6 months) and IDHwt (37.9 months) was observed. This lack of association was also reported in other studies notably in US and Japan [

21,

22]. This tendency was also observed with glioma grades. In fact, several hypotheses were formulated to explain the better OS of glioma patients with IDH mutation. It has been demonstrated that IDH1/2 catalyzes the oxidative decarboxylation of isocitrate to α-ketoglutarate (α-KG) and is the main source of NADPH in the human brain. Mutation in IDH1 and IDH2 enzymes leads to the reduction of α-ketoglutarate (KG) to 2-hydroxyglutarate (2-HG) and to a low level of NADPH. The 2-HG has properties of an oncometabolite and its accumulation in the cell contributes to oncogenesis. The reduced production of NADPH in addition to NADPH consumption by mutated IDH1 may make gliomas sensitive to irradiation and chemotherapy [

23]. However, patients’ age, composition of tumor population, status of other genes such as 1p/19q and TP53 and their association with IDH can impact the OS and must be considered when analyzing results of studies. In fact, i) oligodendrogliomas grade II generally present positive outcome compared to astrocytomas grade II, so including more oligodendroglioma patients in studies can impact the results of IDH mutation effect on prognosis; ii) IDH mutations are more frequent in young patients, which have generally good prognosis. iii) IDH mutation was strongly associated with the 1p/19q co-deletion and the TP53 mutation. In grade II oligodendrogliomas, an association between the IDH mutation and the 1p/19q co-deletion was reported and a prolonged survival in patients with IDH mutation could simply be due to the 1p/19q co-deletion; iv) in astrocytomas grade II, TP53 mutations were reported as a worse prognostic factor, raising the prognostic impact of IDH mutations in astrocytic tumor [

4]. Thus, the lack of association between the OS and IDH status in our study can be explained by the size and composition of the tumor population (only 3 oligodendrogliomas grade II-III, 25 astrocytomas grade II-III and 46 glioblastomas). Further study is warranted to elucidate any potential interactions between these variables.

While IDH mutation is generally defined as a good prognostic factor in patients with glioma, the impact of HCMV on survival remains controversial. Comparison of patients’ OS according to HCMV infection independently of glioma histology showed a significant association (p=0.009). In fact, mOS of HCMV+ glioma patients was lower (34.8 months) compared to HCMV- ones (63.6 months). This result is in accordance with those obtained in several studies [

5,

6]. When considering glioma grades, the survival analysis showed that HCMV+ glioblastoma patients had significant poor OS (p=0.024) but not in grades II-III glioma. This can be explained by: i) the glioblastoma characteristics (as previously mentioned) that provide favorable molecular and biological microenvironment for HCMV reactivation, while oncomodulatory effects of HCMV would promote tumor progression and thereby contribute to reducing the patient’s OS. In fact, tumor-associated macrophages (TAM) are present in the glioblastoma microenvironment. They display an M2 phenotype and support the establishment of Th2 response (production of cytokines such as IL-10) that can promote immune evasion; they can be also infected by HCMV. It was also demonstrated that high TAM density is a hallmark of reduced overall survival in glioblastoma [

24]. ii) HCMV may also remain latent, during a very long time, in neuro stem cells (NSCs). Its reactivation in these cells promotes gliomagenesis in the glioblastoma microenvironment [25].

The glioma patients’ OS was also determined according to combined HCMV and IDH status. The IDHwt/HCMV+ glioblastoma patients subgroup had the worst prognosis, while the IDHmut/HCMV- subgroup significantly had the best prognosis (p=0.002). According to these data, the questions about the possible interaction between IDH and HCMV and the mechanism by which they can impact the OS are raised. In fact, on the one hand, the IDH1-wt activity detected in primary glioblastomas (which is predominant in our study) is an important factor in metabolic adaptation. It supports an aggressive growth of this tumor despite difficult metabolic conditions [

23]. IDHwt is also more prevalent in glioblastomas and shows more resistance to radiotherapy and chemotherapy than IDHmut cases. So glioblastomas IDHwt show worse prognosis [

23]. On the other hand, HCMV is present in all glioma grades with predominance in glioblastomas and is known to play a role in increasing the tumor aggressiveness; moreover its systemic infection decreases the OS of glioblastoma patients [

5]. The lack of association between HCMV presence and IDH status in the present study suggests that HCMV and IDH act as independent factors. Thus, the poor survival observed in IDHwt/HCMV+ patients can be related to the cumulative action of these two probably independent factors. Larger studies are needed to elucidate the links/potential interaction between HCMV and IDH status.