Healthcare workers (HCWs) are at the epicenter in times of a calamity and are pivotal in the overall response during outbreaks. In times like these, they are at a heightened risk of physical and psychological exhaustion and anxiety due to increased workload with longer working hours, inadequate sleep, and the constant fear of contracting the disease.

Schaufeli et al. [

1] consider “job dedication” to be a crucial aspect of work engagement, which can potentially mitigate burnout. Tedeschi and Calhoun [

2] posit that despite being faced with traumatic events, individuals are able to perceive positive effects in terms of deriving meaning of their situation that can be adaptive, as it provides opportunity for growth for the HCW. Through our study, we explored anxiety and burnout among HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the extent to which these outcomes were associated with work-related factors, specifically job dedication, teamwork, feeling of appreciation and perception and communication of policies. We were further interested in perceived positive experiences among HCWs during outbreaks.

We conducted a cross-sectional online study in KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital (KKH), an 830 bedded hospital that provides tertiary care services to women and children in Singapore. We invited approximately 3500 HCWs including medical professionals i.e., registered doctors and nurses, allied health workers and auxiliary staff members bearing a valid work email address via email or online staff portals to participate. The data was gathered between 7 April–30 May 2020, during which COVID-19 cases were at their peak and also a nationwide lockdown (known as Circuit Breaker) was in place.

The General Anxiety Disorder 7-item (GAD-7) instrument was used to measure anxiety [

3]. The scores ranged between 0 and 21. Those who scored 10 or above were classified as reporting high anxiety. We measured burnout using a validated [

4] non-proprietary single-item burnout question derived from the Physician Work-Life scale. Those scoring 3 or above were classified as reporting burnout. The 3-item Job Dedication subscale of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale was used, where higher scores (ranging from 0-6) indicated high job dedication.

Factors relating to policies and communication were assessed using questions relating to a) timely availability of information and updates b) reliability of information provided, and c) understanding of policies and protocols. Workplace support was examined by asking questions relating to teamwork and if the staff felt appreciated by the department or hospital. Workplace environment was determined based on factors such as working longer than usual, having night duties, close contact with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 patients, and if the staff had previously served during the SARS pandemic. We ran multi-variable logistic regression models separately for anxiety and burnout but kept all other variables consistent in both models. We presented the coefficients and odds ratio and their 95% confidence intervals for both models. A 5% level of significance was considered statistically significant. Stata 15.1 (StataCorp LP, USA) was used to carry out the analyses.

A total of two hundred and twenty-seven (n = 227) HCWs participated in the study. The mean age of the participants was 38.24 (standard deviation (SD) = 11.11) years. Overall, 95% (n = 216) of the respondents were females, 50% (n = 114) were Chinese and the remaining (n = 113) belonged to Indian, Malay or other racial groups. A percentage of 61% (n = 138) were nurses, 15% (n = 34) doctors, 11% (n = 24) allied health professionals and 14% (n = 31) worked in other roles. A total of 67% (n = 152) of HCWs had either occasional or daily contact with confirmed or suspected patients with COVID-19, 59% (n = 135) had night shifts, 30% (n = 68) reported working longer hours than usual and 27% (n = 62) were HCWs during SARS. Most of the respondents, 92% (n = 209), had positive perception of the policies and the corresponding communication, and 23% (n = 52) felt that their team had been working well together. A percentage of 28% (n = 64) always felt appreciated by the department or hospital. The mean job dedication score was 4.43 (SD = 1.07).

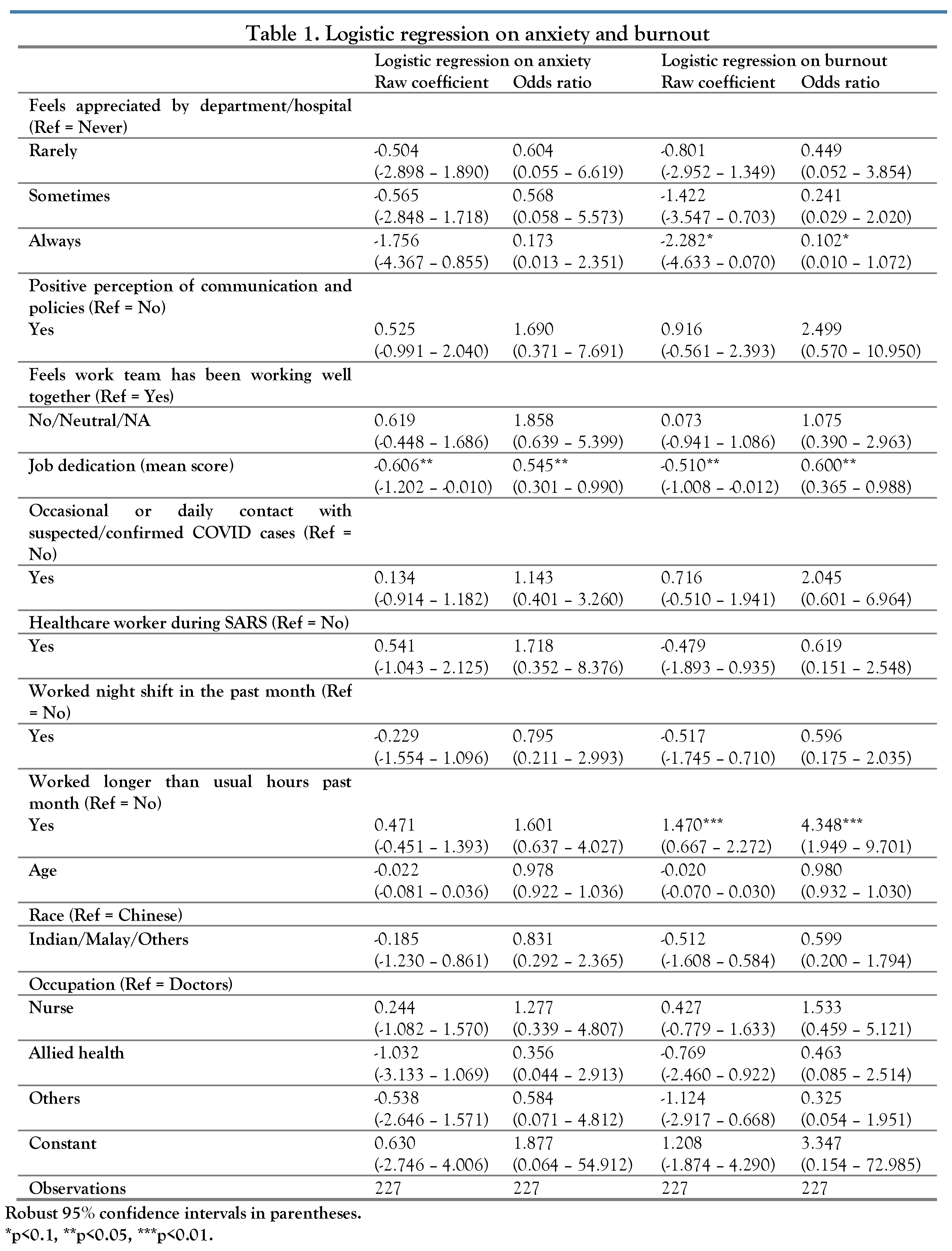

Overall, 14% of the sample reported having high anxiety and 19% reported experiencing burnout. The only factor statistically significantly associated with anxiety was job dedication, where a higher level of job dedication was associated with decreased likelihood of the worker having high levels of anxiety (odds ratio (OR) = 0.545; 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.301; 0.990) (

Table 1). Job dedication was also a significant factor for predicting burnout, with workers having a higher level of job dedication being less likely to endure high levels of burnout (OR = 0.600; 95% CI: 0.365; 0.988). Those who worked for longer hours were more than four times more likely to experience high levels of burnout than those who did not (OR = 4.348; 95% CI: 1.949; 9.701) (

Table 1).

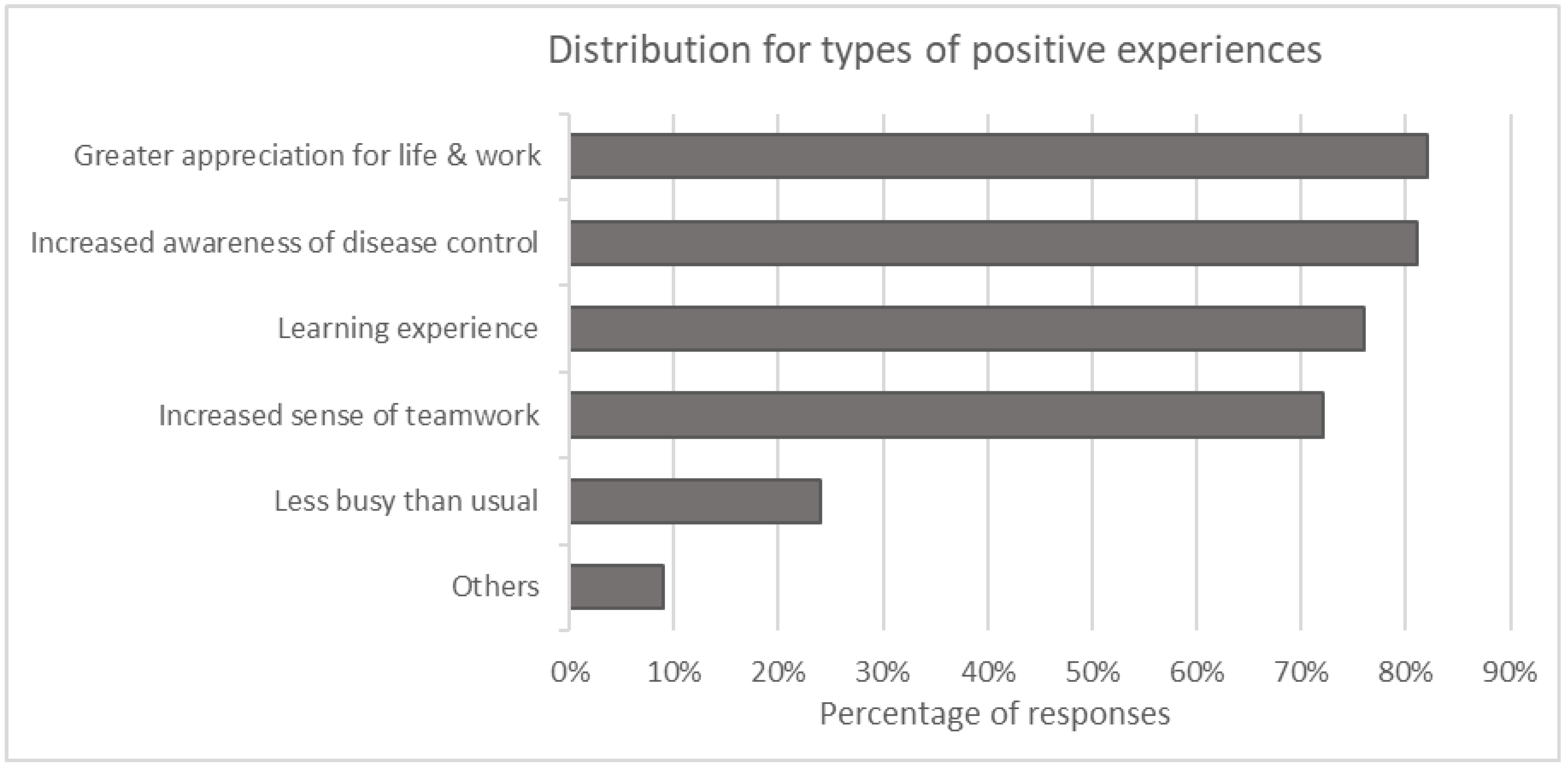

A total of 54% (n = 123) of the participants derived positive experiences out of the situation (

Figure 1). Of these 123 individuals, more than 80% found the pandemic situation to have increased their appreciation of life and work, and an increased awareness of disease control. This was closely followed by observing the situation as a learning experience and having heightened sense of togetherness, which were felt by about 70% of the individuals.

Our findings are consistent with prior studies that have reported poorer HCW outcomes during the pandemic [

5]. We further found that a higher level of job dedication was protective, as it potentially creates a heightened sense of purpose and personal satisfaction. HCWs who reported high job dedication were less likely to be anxious or burnt out. Our findings showed that working longer hours during a pandemic worsened burnout. Taken together, our study suggests the importance of balancing work job hours and job dedication among the HCWs during times of increased load on the healthcare system. This is similar to a study by Jang et al. that attributed the high prevalence of emotional exhaustion to long-term COVID-19 work participation and having to work in a risky workplace. They also highlighted that workplace factors such as insufficient break time, concern for safety, increased workload contribute to psychological distress [

6].

Our study showed that 92% of HCWs had positive perception of the policies and their communication. An effective and integrated communication system is critical during a pandemic response. A key lesson learnt during the SARS pandemic was the importance of rapid and accurate information collation and transmission and, to keep the HCWs and the members of the public informed in a timely manner [

7]. Therefore, it was essential that trustworthy, updated evidence-based, accurate and credible information was circulated to all HCWs in a timely fashion to prevent misinformation.

The positive experiences of HCWs should be noted. For example, hospital workers reported to have an increased awareness of disease control. This would help the hospital staff to be better prepared for the future. Some participants reported that working during a pandemic had increased their appreciation for life and work. They found that the situation provided a positive learning experience and an increased sense of togetherness.

Our study has some limitations. First, we conducted our survey in one hospital serving women and children and thus the generalizability of our findings is limited. Second, participation in the study was voluntary and 95% of our participants were females, which may indicate a self-selection bias. Finally, being a cross-sectional survey, our research is only a snapshot in time.

In conclusion, we wish to highlight the need for advanced interventions in times of crisis to address mental-health concerns of employees and to safeguard their emotional and psychological wellbeing.

Factors such as increasing job dedication and positive experiences in the workplace may be useful in mitigating anxiety and burnout in staff during such times.