Case report

A 50-year-old male presented at the emergency department of All India Institute of Medical Sciences Jodhpur, Rajasthan, India with headache for two months, weakness of both lower limbs for 15 days, and altered sensorium and aphasia for one day. He had an episode of fever associated with vomiting 20 days back. The symptoms were sudden in onset and there was no history of trauma. On admission (day 0), the patient was afebrile with stable vitals and a Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) of 10/15 (E3V2M5). Both pupils were of normal size and reactive. Neuromuscular examination revealed left-sided facial palsy and Grade 4 power in left upper limb (sub-optimal movement against resistance). There were no meningeal or cerebellar signs and no other cranial nerve deficits. The rest of the systems were within normal limits. He had no history of diabetes mellitus or other comorbidities. The hematological and biochemical investigations were unremarkable. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis (day +1) showed raised leukocyte count (22 cells/mm3) with lymphocytic pleocytosis, normal glucose (57 mg/dL) and mildly raised protein (105 mg/dL). Gram staining of CSF revealed occasional pus cells with no bacterial or fungal elements. Ziehl-Neelsen staining was negative for acid-fast bacilli. Bacterial and fungal cultures did not grow any pathogenic organism. Cryptococcal antigen test in serum and CSF was negative. Cepheid's cartridge based nucleic acid amplification test (CBNAAT) Xpert MTB/RIF assay (Sunnyvale, CA, USA) was negative for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Non-contrast computed tomography (NCCT) of the brain (day +2) revealed right basal ganglia lesion with perilesional edema. Contrast enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of brain (day +2) showed multiple coalescent abscesses in the right basal ganglia and corpus callosum, extending across the midline into the left parasagittal region with associated ventriculitis. The patient was administered dexamethasone 10 mg IV bolus, followed by 4 mg IM every 6 hours for five days. His GCS improved to 14/15 (E4V5M5) on day +5. Based on clinical suspicion of tuberculous brain abscess, antitubercular treatment (ATT) comprised of isoniazid (300 mg), rifampicin (450 mg), pyrazinamide (1200 mg), ethambutol (1000 mg) and streptomycin (750 mg IM) was initiated. He was discharged from the hospital on day +7 with oral dexamethasone 4 mg thrice daily and ATT, and advised to attend the neurosurgery outpatient department after four weeks for follow-up.

A month after discharge (day +37), the patient was re-admitted to the emergency with altered sensorium and respiratory distress for two days and aphasia for one day, with history of loss of consciousness. He was afebrile with a GCS of 7/15 (E2V1M4) on admission. A follow-up CECT of the brain (day +37) revealed multiple coalescent ring enhancing lesions in the right basal ganglia, extending across the midline to the left parasagittal region and basal part of left frontal lobe. There was a significant increase in perilesional edema with leftward midline shift of 18 mm and dilatation of bilateral ventricular system (

Figure 1). He was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) for ventilator support (day +37). The hematological investigations revealed leukocytosis (12.64×10

3/µL) with 88.6% neutrophils, 6.9% lymphocytes, 4.2% monocytes, 0.1% eosinophils, and 0.2% basophils. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 42 mm/h and C-reactive protein was 6.8 mg/L. Analysis of CSF (day +38) showed raised leukocyte count (35 cells/mm

3) with lymphocytic pleocytosis, normal glucose (62 mg/dL) and raised protein (218 mg/dL). The patient underwent right frontotemporal craniotomy and evacuation of abscess, with external ventricular drain placement in the right frontal horn of the lateral ventricle (day +40). His consciousness improved following surgical intervention. Post-operatively, the patient received ceftriaxone 2 g IV every 12 h for three days, amikacin 750 mg IV once a day for three days and metronidazole 500 mg IV every 8 h for three days. Dexamethasone and ATT were continued according to the previous regimen.

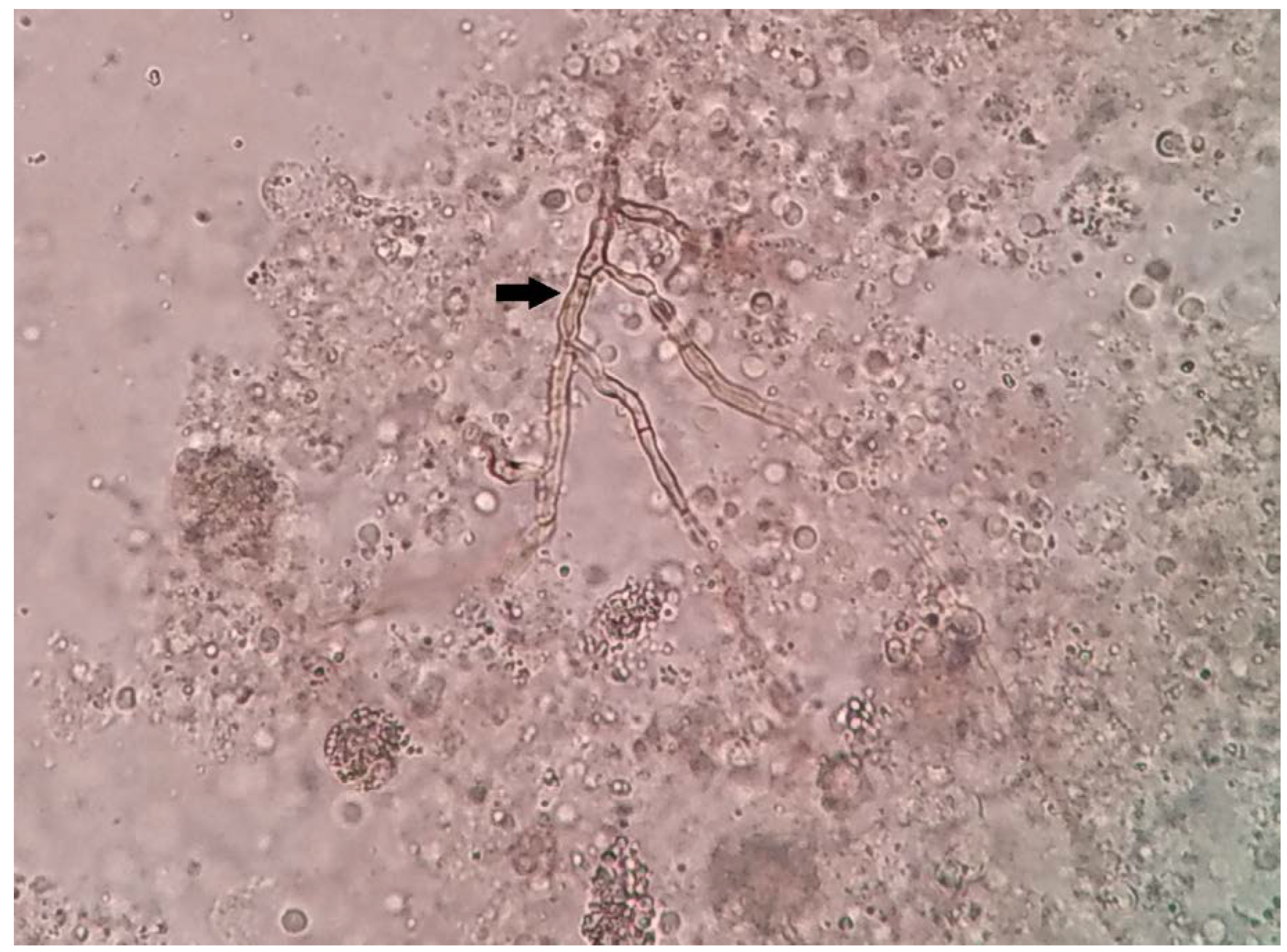

The pus aspirated from the lesion was sent for histopathological and microbiological examinations. Direct microscopy (20% potassium hydroxide mount) revealed pigmented septate fungal hyphae (

Figure 2). Histopathological examination showed necrotizing granulomatous inflammation with brownish black, irregular hyphal elements on hematoxylin eosin staining. GeneXpert MTB/RIF assay (CBNAAT) was negative for

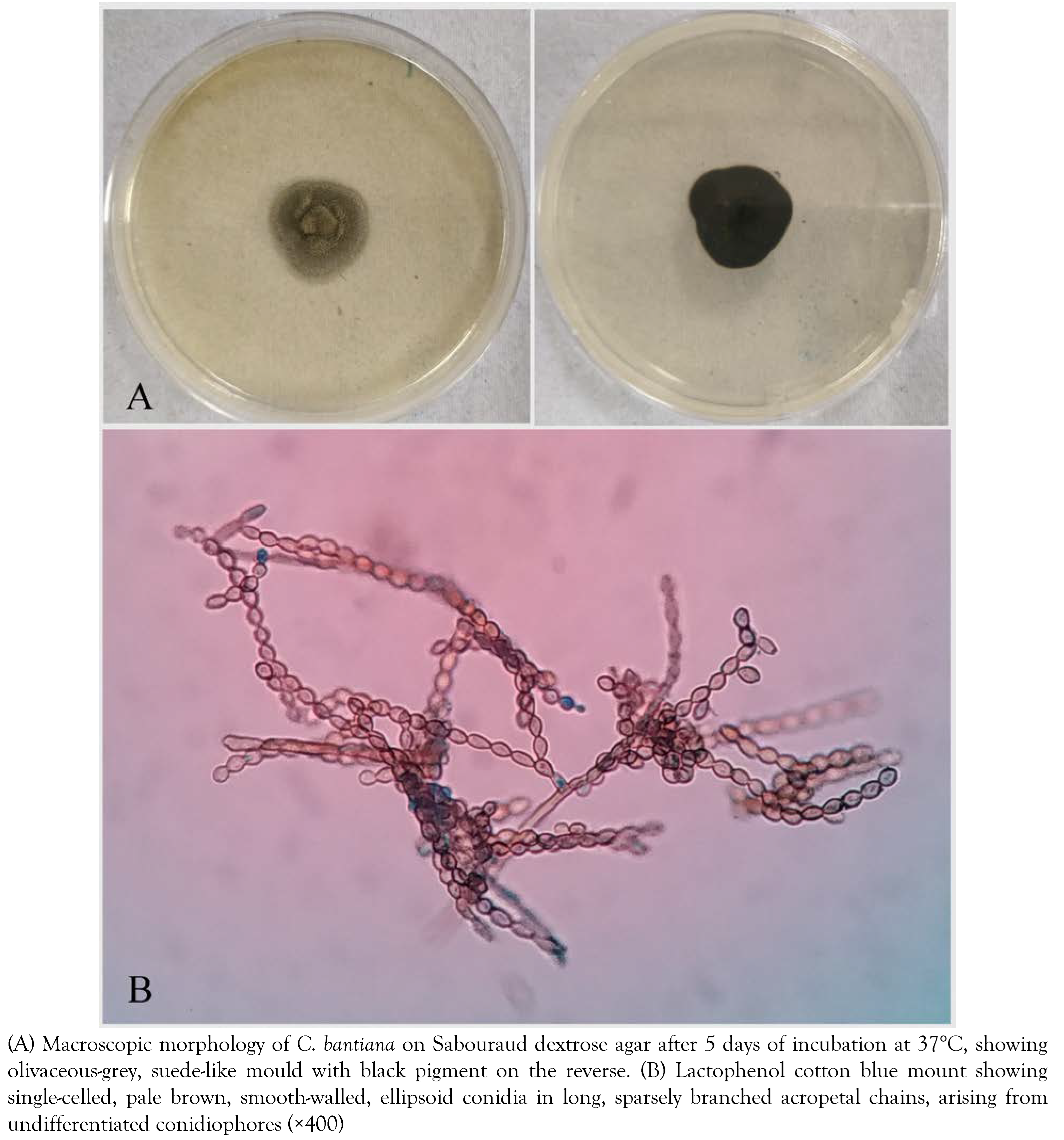

M. tuberculosis. In view of fungal infection, ATT was discontinued and intravenous liposomal amphotericin B (10 mg/kg/day in 5% dextrose over 1 hour) and voriconazole (6 mg/kg IV twice daily on day 1, followed by 4 mg/kg twice daily for the remainder of the treatment) were initiated (day +40). Aerobic and anaerobic bacteriological cultures were sterile after 48 hours of incubation. The specimen was inoculated on Sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA) with gentamicin and 0.01% cycloheximide and incubated at 25°C and 37°C. The media at both the temperatures showed growth of an olivaceous-grey, suede-like mold with black pigment on the reverse after five days of incubation (

Figure 3A). Lactophenol cotton blue (LPCB) mount revealed single-celled, pale brown, smooth walled, ellipsoid conidia in long, sparsely branched, acropetal chains, arising from undifferentiated conidiophores (

Figure 3B). On the basis of characteristic microscopic morphology, resistance to cycloheximide, positive urease test and growth at 42°C, a presumptive identification of

Cladophialophora bantiana was made (day +46). The identity of the isolate was confirmed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region of ribosomal DNA using primer pair ITS1 (5′-GTCGTAACAAGGTTTCCGTAGGTG-3′) and ITS4 (5′-TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3′), and comparing the sequence with the National Centre for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) nucleotide database using basic local alignment search tool (BLAST). The ITS sequence (671 bp) of the isolate showed 100% homology to

C. bantiana GenBank sequences BMU01221 (MW205713) and BMU00225 (MW205712). The sequence was deposited in the GenBank ITS database and published in the NCBI database on 28 February 2021 under the name

Cladophialophora bantiana isolate IL4481 with accession number MW651767. Antifungal susceptibility testing was performed using broth microdilution method according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) document M38 A2. Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values for amphotericin B, voriconazole, posaconazole, itraconazole, caspofungin, anidulafungin and micafungin were 1.0 μg/mL, 0.5 μg/mL, 0.25 μg/mL, 0.5 μg/mL, 8.0 μg/mL, 8.0 μg/mL and 8.0 μg/mL, respectively.

The patient was weaned off mechanical ventilation on day +46 and transferred to the neurosurgery ward with ongoing antifungal treatment. On day +56, he developed high grade fever with altered sensorium, tachypnea, respiratory distress and a fall in oxygen saturation, for which he was transferred to the ICU and re-intubated. Chest X-ray being suggestive of pneumonitis, he was started on broad spectrum antibiotics comprised of meropenem (1 g IV every 8 hours) and amikacin (15 mg/kg IV in two divided doses). However, his clinical condition deteriorated and he died due to multiple organ failure on day +59.

Discussion

We report a case of brain abscess caused by

Cladophialophora bantiana in an immunocompetent male that was initially misdiagnosed as tuberculoma and treated with antitubercular therapy. A delay in the diagnosis resulted in a fatal outcome despite surgical intervention and antifungal therapy.

C. bantiana is a highly neurotropic fungus belonging to the order Chaetothyriales, and it accounts for nearly 50% of the cases of brain abscess caused by phaeoid fungi [

1]. The disease has a worldwide distribution with the majority (57.3%) of the cases being reported from Asian countries, particularly from India (50%) [

3]. In the past two decades, India has witnessed an exponential rise in

C. bantiana brain abscesses from 16 cases between 1950 and 2000 to 47 cases between 2001 and 2020 [

2,

3,

4,

5]. A retrospective analysis of medical records over a 10-year period (2004-2014) from a tertiary care institute in North India revealed that

C. bantiana accounted for 8.1% of all fungal brain abscess cases [

3]. To date, the largest series of 10 cases over a period of 27 years has been reported from a neuroscience institute in Southern India [

6]. The disease affects both immunocompetent and immunocompromised individuals with a slightly higher prevalence in the former group, and a male preponderance [

1,

3].

C. bantiana is a ubiquitous soil saprophyte and infection is probably acquired through inhalation of airborne conidia, followed by hematogenous dissemination to the brain [

3]. Direct extension from adjacent paranasal sinuses or from a subcutaneous traumatic inoculation site has also been suggested. The presence of melanin in the hyphal wall confers protection against oxidative stress and facilitates CNS invasion [

7,

8].

Brain involvement manifests in the form of SOL and presents as headache, hemiparesis, seizures, altered sensorium, fever, vomiting, aphasia, dysarthria, and visual disturbance [

3,

8]. The lesions are predominantly observed in the frontal (53.1%) and parietal (42.3%) lobes and less commonly in the occipital region (10%) [

1]. Diagnosis is often delayed due to clinical and radiological similarities with other common SOL like tumor or tuberuloma, [

1,

9]. as happened in the present case. A retrospective analysis of 124 cases of

C. bantiana brain abscess by Chakrabarti et al. showed that diagnosis was delayed with a mean duration of 115 days after developing symptoms [

3].

The laboratory diagnosis of cerebral phaeohyphomycosis is challenging. In the absence of specific biomarkers or serological tests, the diagnosis chiefly relies on microscopic demonstration of pigmented fungal hyphae in clinical specimens and isolation of the fungus in culture. Although presumptive identification can be made on the basis of microscopic morphology of cultured strains, a definitive identification to species level can only be achieved by ITS1/ITS2 or D1/D2 sequencing and/or matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) analysis [

10].

Antifungal susceptibility testing is not routinely recommended as breakpoints have not yet been established by CLSI or European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST). Most isolates of

C. bantiana demonstrate low MICs against voriconazole, posaconazole and itraconazole, variable MIC against amphotericin B and high MICs against echinocandins [

3,

8,

10]. Similar findings were observed with our isolate.

Until 2020, there was no consensus guideline for the treatment of invasive phaeohyphomycosis. In February 2021, the European Confederation of Medical Mycology together with the International Society for Human and Animal Mycology and the American Society for Microbiology proposed a set of comprehensive recommendations for diagnosis and management of rare mould infections as a part of the One World-One Guideline initiative [

10]. This global guideline focuses on clinical decision making and treatment approaches against invasive infections caused by rare moulds, including phaeohyphomycosis, while addressing the diagnostic and therapeutic options in different settings. According to this global guideline, complete surgical excision of abscess together with combination antifungal therapy should be the treatment of choice. None of the drugs has been found to be independently associated with improved survival. Liposomal AmB (3-10 mg/kg/day) alone or in combination with a triazole and/or echinocandin or voriconazole monotherapy (2 × 6 mg/kg/day on day 1; then 2 × 4 mg/kg/day from day 2) together with 5-flucytosine (50-150 mg/kg/day) are recommended as the first-line treatment for

C. bantiana brain abscess [

10]. A recent systematic review by Kantarciogli et al. showed a survival rate of 40.8% among patients who received AmB [

8]. The use of AmB deoxycholate is discouraged due to poor CNS penetration and potential risk of adverse effects. The newer triazoles like voriconazole and posaconazole have good CNS penetration and favorable in vitro activity against

C. bantiana. Echinocandins lack CSF penetration and demonstrate poor in vitro activity against

C. bantiana, [

3]. as observed in our isolate.

Despite aggressive medical and surgical interventions, the mortality rate of

C. bantiana brain abscess remains very high (65-70%), [

1,

3]. with the majority of the deaths occurring between one month and six months following admission to the hospital, irrespective of the treatment modality [

8]. This can be attributed to delay in the diagnosis, variable in vitro antifungal susceptibility of the fungus, and the extent of lesion. In our case, a fungal etiology of the brain abscess was not in the diagnostic consideration as it is relatively rare in immunocompetent individuals and the clinical and radiological features were mimicking those of tuberculoma, which accounts for the majority of the intracranial SOL in India [

11]. Moreover, a negative CSF GeneXpert does not rule out CNS tuberculosis due to low sensitivity of the assay. All these factors resulted in a diagnostic dilemma, which contributed to fatal outcome in our case.