Barriers to Disinfection of Mobile Touch Screen Devices Amongst a Multidisciplinary Team in Intensive Care Units at a Tertiary Hospital

Introduction

Methods

Setting and questionnaire

Eligibility and sample size

- n—required sample size

- P—percentage occurrence of a state or condition

- E—percentage maximum error required

- Z—value corresponding to level of confidence required

Statistical analysis and ethics

Results

Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of interest

Note

Appendix A. Questionnaire

- Age

- <20

- 21–30

- 31–40

- 41–50

- >50

- Sex

- Male

- Female

- Intensive care unit

- C27

- D12

- D13

- D20

- D22

- C26

- Profession

- Medical doctor

- Nurse

- Physiotherapist

- Dietician

- Other (please specify):

- Rank

- Consultant/senior specialist

- Registrar

- Medical officer

- Nurse

- Student

- Other (please specify):

- Working time

- Day shift

- Night shift

- Average number of patients you interact with per day in the intensive care unit

- <5

- 5–10

- >10

- Do you own a mobile touch screen electronic device (cell phone, iPad, tablet etc.)?

- Yes

- No

- How often do you answer a mobile phone call in the intensive care unit?

- Never

- Sometimes

- Always

- Reason for answering or using a touch screen device at the patient’s bedside

- To look up medical information

- Consult regarding patient management or give advice to other clinicians

- Answer personal calls

- Other (please specify):

- How often do you use a handheld/personal electronic device other than a cell phone in the intensive care unit?

- Never

- Sometimes

- Always

- How often do you clean your touch screen electronic device after using it in the intensive care unit?

- Never

- Sometimes

- Always

- Do you believe electronic devices play a role in spreading resistant microorganisms in the intensive care unit?

- Yes

- No

- Do you think electronic device use should be banned in the intensive care unit?

- Yes

- No

- Are you concerned that cleaning your electronic device with a disinfectant will harm it?

- Yes

- No

- Do you know of any policy or guideline on cleaning your electronic device?

- Yes

- No

- Do you think you should wash your hands before and after using your touch screen device in the intensive care unit?

- Yes

- No

- How often do you touch a patient or their surroundings when working in the intensive care unit?

- Never

- Sometimes

- Always

- How do you decontaminate your touch screen electronic device?

- Alcohol based medium

- Chlorhexidine based medium

- Dry cloth

- Sterile water

- Ammonium based medium

- I don’t decontaminate it

- Other (please specify):

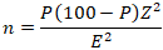

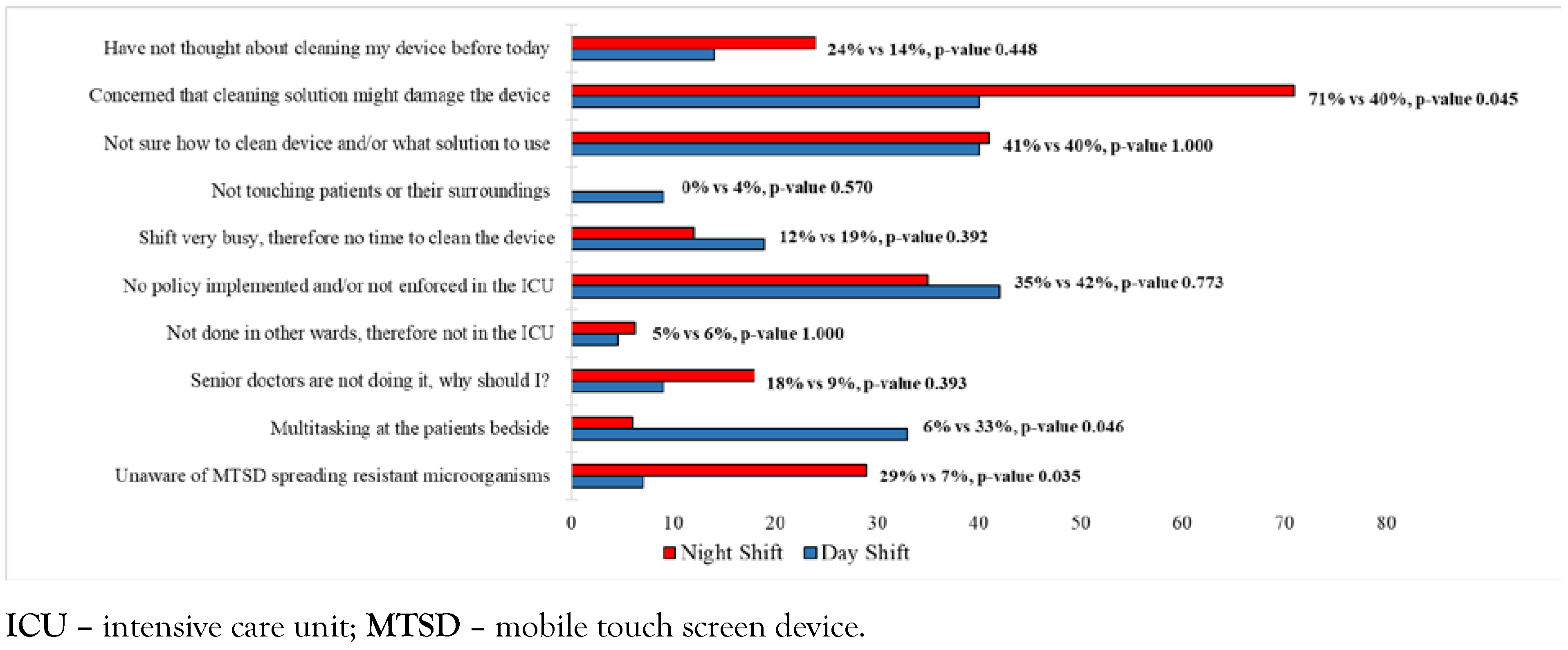

- If you don’t disinfect your electronic touch screen device in the intensive care setting regularly, what is/are the reason(s)? (More than one can be selected)

- Unaware of potential risk

- Multitasking at bedside

- Senior doctors not doing it

- Not done in other wards therefore not in the ICU

- No policy/not enforced to do it

- Day shift very busy therefore no time

- Night shift very busy therefore no time

- They are not touching patient or their surroundings

- Not sure how to clean devices/what solution to use

- Worried cleaning solution might damage the device

- Have not thought about cleaning devices before today

- Other (please specify):

References

- Martina, P.F.; Martinez, M.; Centeno, C.K.; VONSpecht, M.; Ferreras, J. Dangerous passengers: Multidrug-resistant bacteria on hands and mobile phones. J Prev Med Hyg. 2019, 60, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, X.Y.A.; Chong, S.Y.; Koh, S.E.A.; Yeo, B.C.; Tan, K.Y.; Ling, M.L. Healthcare workers’ beliefs, attitudes and compliance with mobile phone hygiene in a main operating theatre complex. Infect Prev Pract. 2020, 2, 100031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taherdoost, H. Determining sample size; How to calculate survey sample size. Int J Econ Manag Systems. 2017, 2, 237–239. [Google Scholar]

- Missri, L.; Smiljkovski, D.; Prigent, G.; et al. Bacterial colonization of healthcare workers' mobile phones in the ICU and effectiveness of sanitization. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2019, 16, 97–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manning, M.L.; Davis, J.; Sparnon, E.; Ballard, R.M. iPads, droids, and bugs: Infection prevention of mobile handheld devices at the point of care. Am J Infect Control. 2013, 41, 1073–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graveto, J.M.; Costa, P.J.; Santos, C.I. Cell phone usage by health personnel: Preventive strategies to decrease risk of cross infection in clinical context. Texto Contexto Enferm. 2018, 27, e5140016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

© GERMS 2021.

Share and Cite

Opperman, C.J.; Khan, F.; Piercy, J.L.; Samodien, N. Barriers to Disinfection of Mobile Touch Screen Devices Amongst a Multidisciplinary Team in Intensive Care Units at a Tertiary Hospital. Germs 2021, 11, 329-336. https://doi.org/10.18683/germs.2021.1270

Opperman CJ, Khan F, Piercy JL, Samodien N. Barriers to Disinfection of Mobile Touch Screen Devices Amongst a Multidisciplinary Team in Intensive Care Units at a Tertiary Hospital. Germs. 2021; 11(2):329-336. https://doi.org/10.18683/germs.2021.1270

Chicago/Turabian StyleOpperman, Christoffel J., Farheen Khan, Jenna L. Piercy, and Nazlee Samodien. 2021. "Barriers to Disinfection of Mobile Touch Screen Devices Amongst a Multidisciplinary Team in Intensive Care Units at a Tertiary Hospital" Germs 11, no. 2: 329-336. https://doi.org/10.18683/germs.2021.1270

APA StyleOpperman, C. J., Khan, F., Piercy, J. L., & Samodien, N. (2021). Barriers to Disinfection of Mobile Touch Screen Devices Amongst a Multidisciplinary Team in Intensive Care Units at a Tertiary Hospital. Germs, 11(2), 329-336. https://doi.org/10.18683/germs.2021.1270