Abstract

Introduction: Recently, a marked increase in the rate of colistin resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae was observed in Croatian hospitals and the outpatient setting. This prompted us to analyze the molecular epidemiology of these isolates and the mechanisms of spread. Methods: In total 46 colistin-resistant K. pneumoniae isolates from five hospitals and the community were analyzed. The presence of genes encoding broad and extended-spectrum β-lactamases, plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamases and carbapenemases was determined by PCR. Plasmids were characterized by PCR based replicon typing. Isolates were genotyped by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Virulence traits such as hemolysins, hyperviscosity and resistance to serum bactericidal activity were determined by phenotypic methods. Results: High resistance rates were observed for cefuroxime, ceftazidime, cefotaxime, ceftriaxone and ertapenem, ciprofloxacin and gentamicin. The majority of OXA-48 producing isolates were resistant to ertapenem but susceptible to imipenem and meropenem. Nine strains transferred ertapenem resistance to E. coli recipient strain. Thirty-nine strains were phenotypically positive for ESBLs and harbored group 1 of CTX-M β-lactamases. OXA-48 was detected in 39 isolates, KPC-2 in four and NDM-1 in one isolate. The isolates belonged to six PFGE clusters. All isolates were found to be resistant to serum bactericidal activity and all except four strains positive for KPC, produced β-hemolysins. String test indicating hypermucosity was positive in only one KPC producing organism. Conclusions: The study demonstrated the ability of K. pneumoniae to accumulate different resistance and virulence determinants. We reported dissemination of colistin resistant K. pneumoniae in five hospitals, located in different geographic regions of Croatia and in the outpatients setting. mcr genes responsible for transferable colistin resistance were not found, indicating that resistance was probably due to chromosomal mutations.

Introduction

Klebsiella pneumoniae is an opportunistic pathogen that causes a variety of infections in hospitalized patients, including ventilator-associated pneumonia, septicemia and urinary tract infections. It can readily acquire resistance to a wide range of antimicrobials due to the production of extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBL), AmpC-β-lactamases and carbapenemases encoded on mobile genetic elements. Colistin is an old antibiotic with significant activity against the Gram-negative bacteria including K. pneumoniae, which is now being administered as a salvage therapy in patients in whom none of the other antibiotics are active against such isolates. The most common mechanism of colistin resistance in K. pneumoniae is the inactivation of the mgrB gene, encoding a negative feedback regulator of the PhoQ-PhoP signaling system which activates the pmr system, responsible for the modification of the lipopolysaccharide polymyxin target.[1,2,3] Inactivation of the mgrB gene can be mediated by sequence IS1F or IS5-like, disrupting the gene.[3] Moreover, high-level resistance to colistin was found to be mediated by various mutations in the crrB gene among carbapenemase producing K. pneumoniae from Europe, Turkey, South America and South Africa.[4] Plasmid-mediated colistin resistance is associated with acquisition of mcr-1 or mcr-2 genes and is the dominant mechanism of colistin resistance in Escherichia coli, particularly among animal isolates.[5,6] Recently, plasmid-mediated colistin resistance was also reported in K. pneumoniae, but it is still very rare.[7] Colistin resistance in K. pneumoniae is of great concern and is usually associated with carbapenemase and ESBL production.[6,7] OXA-48, VIM-1, or KPC are most frequently linked with colistin resistance. KPC positive and colistin resistant isolates were shown to belong predominantly to the widespread clone ST258 with a few isolates belonging to ST15 and ST273 reported in USA, Greece and Italy.[8,9,10] The majority of the isolates harbored KPC-3 allelic variant and co-produced TEM-1 and OXA-9 contributing to resistance to beta-lactam inhibitor combinations. Colistin resistance was found to be linked to increased virulence in Galleria mellonella, model. The first colistin resistant K. pneumoniae isolates in Croatia were recently reported in the frames of the study on the dissemination of OXA-48 carbapenemases.[11,12]

Analysis of colistin resistance mechanisms of K. pneumoniae and A. baumannii from Croatia was recently published.[13] Whole genome sequence analysis revealed several mutations in the mgrB and rpo genes to be responsible for colistin resistance in K. pneumoniae.

After the first sporadic cases, alarming diffusion of this important resistance determinant was observed in 2019 in several hospitals located in different geographic regions of Croatia and also in the outpatient setting. This prompted us to analyze the molecular epidemiology and routes of spread of this important hospital pathogen.

Methods

Bacterial isolates

In total 46 colistin resistant non-duplicate (one per patient) K. pneumoniae isolates were collected in seven centers located in different geographic regions of Croatia in order to cover the whole country and to get an insight on dissemination of this important resistance determinant. The participating centers were as follows: General Hospital Karlovac (23 isolates), University Hospital Center Sestre Milosrdnice in Zagreb (2 isolates), University Hospital Center Rijeka (4 isolates), Andrija Štampar Public Health Institute in Zagreb (6 isolates), Public Health Institute Sisak (4 isolates), University Hospital Center Split (4 isolates) and General Hospital Dubrovnik (3 isolates). The isolates originated from various clinical specimens including invasive, clinically relevant (n=33: blood cultures n=2, urine n=28, wound swabs n=2, intraoperative specimen n=1) and surveillance cultures (n=13: tracheal aspirates n=5, bronchoalveolar lavage n=3, rectal swabs n=3, stool n=2) during 2019 except for five outpatient strains which originated from 2016 to 2018. The isolates were identified in the participating centers by conventional biochemical testing, Vitek 2 or MALDI-TOF MS (matrix assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry). The isolates that were stored in the participating centers were sent for molecular analysis to University Hospital Centre Zagreb in the frames of the retrospective study.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing and phenotypic tests for detection of ESBLs, plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamases and carbapenemases

Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of amoxicillin alone and combined with clavulanate, piperacillin/tazobactam, cefazoline, extended-spectrum cephalosporins (ESC: ceftazidime, cefotaxime, ceftriaxone), cefepime, imipenem, meropenem, gentamicin, ciprofloxacin and colistin were determined by the broth microdilution method in Mueller-Hinton broth and 96 well microtiter plates according to CLSI standards[14] and for colistin according to the EUCAST standard [http://www.eucast.org]. The susceptibility to fosfomycin was determined by agar dilution. The susceptibility to ertapenem, sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim, tetracycline and chloramphenicol was determined by disk-diffusion test. The isolates were classified as multidrug-resistant (MDR), extensively drug-resistant (XDR) or pandrug-resistant (PDR) as described previously by Magiorakos et al.[15]

The double disk synergy test (DDST) was done with conventional amoxicillin/clavulanate, ceftazidime, cefotaxime, ceftriaxone and cefepime disks that were applied 20 mm apart to detect ESBLs.[16] CLSI combined disk test using ceftazidime, cefotaxime, ceftriaxone and cefepime disks with and without clavulanic acid was performed to confirm ESBLs production.[14] Plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamases were detected by combined disk test using cephalosporin disks with 3-aminophenylboronic acid (PBA).[14] A modified Hodge test (MHT) and the carbapenem-inactivation method (CIM) were used to screen for the presence of carbapenemases.[17,18] Additionally, the isolates were tested by combined disk tests with imipenem and meropenem alone and combined with PBA, EDTA or both to screen for KPC, MBLs, or simultaneous production of KPC and MBL, respectively.

Conjugation

Colistin, ertapenem and cefotaxime resistance transfer experiments were carried in mating assays employing E. coli J65 recipient strain resistant to sodium-azide.[19] Equal volume of cultures of donor and recipient strains were mixed in Brain-Heart infusion broth and incubated for 18h at 35°C. The transconjugants were selected on MacConkey agar supplemented with either colistin (1 mg/L), ertapenem (1 mg/L) or cefotaxime (2 mg/L) to suppress the recipient strain and sodium azide (100 mg/L) to inhibit the growth of the donor strains.

Molecular detection of resistance genes

A fresh bacterial colony was suspended in 100 µL of sterile, distilled water and boiled at 100°C for 15 min. After centrifugation the supernatant was used as DNA template. Genes conferring resistance to β-lactams, including broad spectrum and extended-spectrum β-lactamases (blaSHV, blaTEM, blaCTX-M, and blaPER-1), plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamases (pAmpC), class A (blaKPC), class B carbapenemases (blaVIM, blaIMP and blaNDM), carbapenem hydrolyzing oxacillinases (blaOXA-48-like) and fluoroquinolone resistance genes (qnrA, qnrB, qnrS) were amplified by PCR using protocols and conditions as described previously.[20,21,22,23] For each PCR reaction 25 µL of emerald master mix, 20 µL of ultrapure water and 1 µL of each primer were mixed with 3 µL of DNA template to obtain the total volume of 50 µL. Genetic context of blaCTX-M genes was determined by PCR mapping with forward primer for ISEcp1 and IS26 combined with primer MA-3 (universal reverse primer for blaCTX-M genes). Flanking regions of blaOXA-48 genes were analysed by PCR using forward primer for IS1999 and reverse primer for blaOXA-48. PCR was used to analyze the inactivation of mgrB genes and to detect plasmid encoded colistin resistance genes mcr-1 and mcr-2.[6]

PCR products were separated in 1% agarose gel and visualized under UV light after staining with ethidium bromide.

Characterization of plasmids

Plasmids were extracted from donor strains and their respective transconjugants with Qiagen (QIAGEN Hamburg, Germany) mini kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After staining with ethidium bromide, the DNA was visualized by ultraviolet light. The size of the plasmid bands was determined by comparison with those of E. coli NTCC 50192 yielding four bands of know sizes of 148, 64, 36 and 7 kb. PCR-based replicon typing (PBRT) was applied to determine the plasmid content of the tested strains.[24] Plasmid extractions obtained from transconjugant strains were subjected to PCR for the detection of KPC and ESBLs in order to determine the resistance gene content of the transconjugants. PBRT was also applied on transconjugants to identify incompatibility groups such as in their respective donors. Positive control strains for PBRT were kindly provided by dr. A. Carattoli (Instituto Superiore di Sanita, Rome, Italy).

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE)

In total 34 isolates, which were available for testing, were subjected to PFGE. Bacterial DNA was prepared and XbaI- was used as restriction endonuclease. Plugs were loaded onto agarose gel and DNA separation was performed with CHEF-DRIII system (Bio-Rad, USA); as described elsewhere.[25] The DNA macrorestriction patterns were compared and analysed using the Gel-Compar software to determine the level of similarity. The dendrogram was computed after band intensity correlation using global alignment with 1.5% optimization and 1% tolerance and unweighted pair-group method using arithmetical averages (UPGMA) clustering. PFGE cluster analysis was carried out with Bionumerics 7.6 (Applied Maths, Belgium) using Dice similarity coefficient and clustering by the UPGMA. Bands smaller than ~50 kb were not included in analysis. Pulsotypes were defined at 80% similarity between macrorestriction patterns. If the strains had two to four different fragments in their Xba patterns they were designed as subtypes. One isolate KC 5852 was subjected to multilocus sequence typing according to the instructions on the Pasteur website.

Infection control measures

Screening methods used for surveillance of nosocomial colonization according to the local ICU procedures include nasal, pharyngeal and rectal swabs as well as urine and stool cultures taken at admission and during ICU stay. Patients are screened for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis (VRE), ESBL producing Enterobacteriaceae and carbapenem and colistin-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii. In case of suspected or confirmed infection, microbiological examination depends on the suspected site of infection (blood culture, tracheal aspirate, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid or urine culture).

Determination of virulence factors

String test was attempted by stretching a mucoviscous string from the colony using a standard bacteriologic loop. If a viscous string >5 mm was formed, isolate was defined as hypermucoviscous.

The production of β hemolysin was tested on human blood agar plate and was considered positive when bacteria were stabbed with a sterile straight wire into 5% human blood agar, and after 18 to 24 h of incubation at 37°C, a clearing zone was observed.

For serum sensitivity testing blood was obtained by venipuncture from three healthy volunteers and was allowed to clot at room temperature for 30 min and overnight at 4°C. After centrifugation at 1,000 g for 15 min at 4°C, serum was removed and pooled. A portion of the pooled serum was decomplemented by heating at 56°C for 30 min and used as test controls. Bacterial susceptibility to serum killing was measured by assessing regrowth after incubation in normal human serum according to Schiller and Hatch method.

Results

Bacterial isolates

The rate of colistin resistant isolates among the total number of K. pneumoniae isolates during the study period was 0.4% (2/420) and (4/875) in University Hospital Sestre Milosrdnice in Zagreb and in University Hospital Center Rijeka respectively, 0.45 % (4/870) in Sisak, 7.9% (126/1590) in University Hospital Split and 9.8% (33/334) in Karlovac. No data were available for Andrija Štampar Public Health Institute because colistin susceptibility is not done as a part of routine diagnostic for outpatient population except in case of carbapenem-resistance when colistin E-test is performed.

Clinical data and outcome

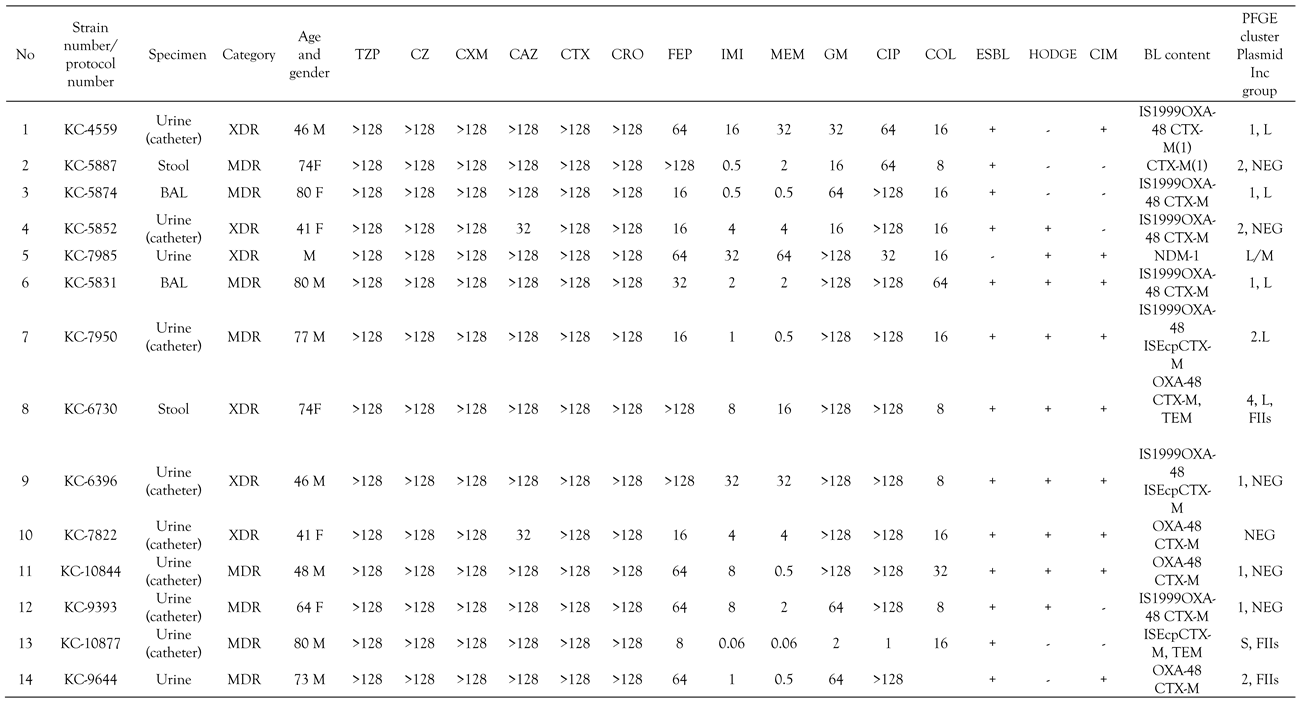

The age of the patients ranged from 41 to 89 years. The majority of the patients from Karlovac hospital were hospitalized at the neurology hospital ward and were immobile due to cerebrovascular insult or motor neuron diseases (Table 1). The route of spread of colistin resistant K. pneumoniae was sharing the same wash basin between patients. Serious comorbidities were recorded in the most patients. Fifteen patients had central nervous system disorders including cerebrovascular insult, intracerebral bleeding, motor neuron diseases and Parkinson disease, four had malignant diseases and two had cardiovascular diseases. Urinary tract infection (UTI) was detected in 28, pneumonia in four, whereas two patients had bloodstream infection and wound infection, respectively. Eleven out of 43 patients (25%) died but the death was due to the underlying disease (all-cause mortality) – Table 1. For four patients the medical records were misplaced. Meropenem combined with colistin was administered in three patients whereas meropenem alone was given to five patients and imipenem to one. Eight patients with UTI received sulfamethoxazole with trimethoprim and one ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin, respectively. Ceftazidime/avibactam was administered in six patients. Amikacin was given as monotherapy in one patient and combined with other antibiotics in two patients. The patients in the outpatient setting from Zagreb and Sisak suffered from UTI or genital infections (prostatitis). The antibiotic choice depended on the hospital center. Meropenem in combination with colistin was the preferred therapeutic option in Karlovac hospital whereas ceftazidime/avibactam was administered in Split, Dubrovnik and Rijeka. Meropenem and imipenem alone were applied if MIC values were in the susceptible range. UTI was treated with sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim or ciprofloxacin providing that in vitro testing showed susceptibility.

Table 1.

Clinical data and virulence factors of colistin resistant K. pneumoniae isolates.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing and phenotypic tests for detection of ESBLs, plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamases and carbapenemases

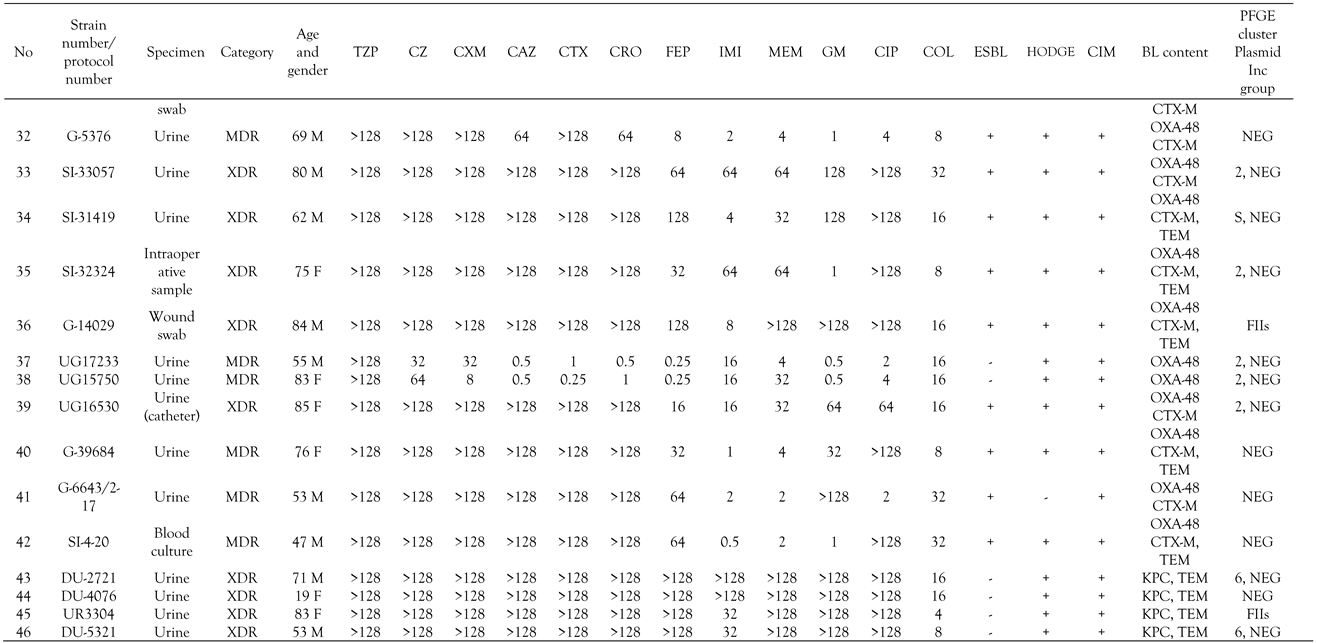

All K. pneumoniae isolates were uniformly resistant to amoxicillin, amoxicillin/clavulanate, piperacillin/tazobactam, cefazoline and colistin. High resistance rates were observed for cefuroxime (45/46, 98%), ceftazidime, cefotaxime, ceftriaxone and ertapenem (44/46, 96%), ciprofloxacin (42/46, 91%) and gentamicin (39/46, 85%). Moderate resistance rates were detected for cefepime (33/46, 72%), imipenem 25/46 (54%) and meropenem 24/46 (52%). Combined disk test with clavulanic acid was positive in all except six strains (40/46, 87%), indicating the production of an ESBL (Table 2). Hodge and CIM test were positive in 31 (67%) and 39 (85%) isolates, respectively, indicating the production of carbapenemase as shown in Table 2. Inhibitor-based tests with PBA and carbapenems was positive in three strains, consistent with production of KPC, whereas inhibitor-based test with EDTA yielded significant augmentation of inhibition zone around carbapenem disks in one strain, being suspicious of MBL production. Twenty-one isolates (43%) were XDR and the rest MDR. XDR isolates were susceptible only to amikacin and ceftazidime/avibactam.

Table 2.

Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs), phenotypic test for β-lactamases, β-lactamase content and plasmid incompatibility group of the tested isolates.

Conjugation

Six OXA-48 positive and three KPC positive strains transferred ertapenem resistance to E. coli recipient strain with the frequency ranging from 2x10-5 to 2.6x10-4. Transconjugants did not harbor any additional resistance determinants to non-β-lactam antibiotics. Cefotaxime and colistin resistance were not transferred from any of the strains.

Molecular detection of resistance genes

All isolates yielded PCR products with primers specific for blaSHV genes, which is consistent with intrinsic SHV-1 or SHV-11 β-lactamase of K. pneumoniae. Thirty-nine strains phenotypically positive for ESBLs tested positive for group 1 of CTX-M β-lactamases as shown in Table 2. OXA-48 was detected in 39 isolates resistant to ertapenem with variable MICs of imipenem and meropenem, whereas blaKPC genes were amplified in four strains uniformly resistant to all three carbapenems. The transconjugants obtained with ertapenem as selective agent had the same blacarb content as their respective donors. blaNDM-1 was found in one strain exhibiting resistance to all carbapenems (Table 2). blaTEM genes were amplified in ten OXA-48 and all KPC producing organisms. blaCTX-M genes were additional only to blaOXA-48, but not to other carbapenemase encoding genes. mcr genes, encoding transferable colistin resistance and qnr genes responsible for reduced susceptibility to fluoroquinolones, were not found. blaOXA-48 genes were preceded by IS1999 insertion sequence in 11 strains whereas ISEcp was found upstream of blaCTX-M gene in only 4 strains. The strains were found to possess wild type mgrB gene by PCR.

Characterization of plasmids

The plasmid of 160 to 170 bp was found in 39 OXA-48 strains. IncL plasmid was identified by multiplex PCR in 8 OXA-48 producing organisms. KPC producing organisms were positive for IncFIIs plasmid while NDM-1 positive strain harbored IncL/M plasmid (Table 2).

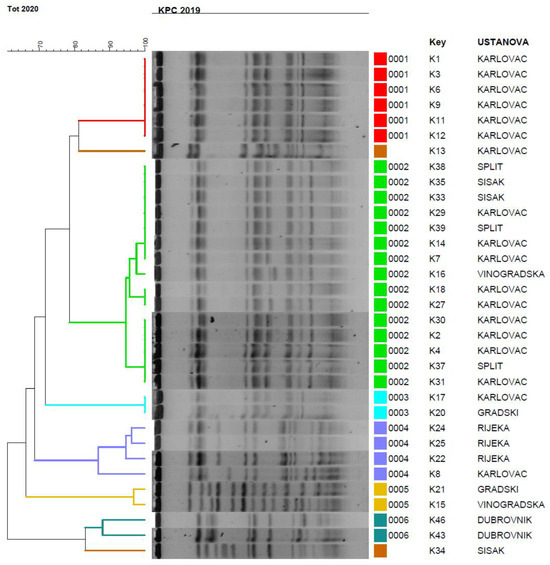

Genotyping

Molecular typing by PFGE identified 6 genetic pulsotypes with highly related isolates (linkage levels >85%) among the 34 tested isolates. The isolates from Karlovac belonged into two pulsotypes with almost identical banding patterns supporting their clonal relatedness (Figure 1). Very similar PFGE profiles were exhibited also for isolates originating from Dubrovnik, Rijeka and Sisak, but certain diversification was observed between the isolates in the same pulsotype. The pulsotype 2 represented the majority of isolates from Karlovac, but also some from other centres like Sestre Milosrdnice Hospital, Split and Sisak (Figure 1). One isolate was singleton. One isolate KC 5852 was found to belong to ST37, the same sequence type previously reported in KPC-2 producing K. pneumoniae from Croatia.

Figure 1.

PFGE dendrogram of K. pneumoniae isolates. Pulsotypes were defined at 80% similarity between macrorestriction patterns. If the strains had two to four different fragments in their Xba patterns they were designed as subtypes. Vinogradska: Sestre Milosrednice hospital in Zagreb The isolates were assigned into six clusters with two isolates having unique PFGE patterns and being designated as singletons.

Determination of virulence factors

All isolates were found to be resistant to serum bactericidal activity and all except four strains positive for KPC, produced β-hemolysins as shown in Table 1. String test indicating hypermucosity was positive in only one KPC producing organism.

Infection control measures

In general hospital Karlovac with outbreak in neurology ICU, infection control measures were implemented and the outbreak was terminated. Infected patients were separated from non-infected patients by cohorting. Patients admitted to the hospitals and healthcare workers were also screened for K. pneumoniae carriage. Furthermore, environmental specimens within the hospital wards such as surfaces surrounding beds, equipment and soap dispensers, were screened for MDR Gram-negative bacteria. The results of the audit were that the healthcare providers were educated by infection control team how to perform hand hygiene and to use personal protective equipment. Moreover, they were instructed for proper disinfection of tools and equipment in the intensive care units and maintenance of catheters, injection practices, and other medical services in adherence with the infection control protocols of the facility. The outbreak was terminated in the neurology intensive care unit when the staff stopped sharing the washing utensils (wash basins) between the patients and each patient obtained his/her own utensils.

Discussion

The study demonstrated a sustained outbreak of colistin resistant K. pneumoniae in five hospitals, located in different geographic regions of Croatia and in the outpatients setting. mcr genes responsible for transferable colistin resistance were not found, indicating that resistance was probably due to mutations in mgrB genes, but experimental data supporting this speculation are required. The clarification of the resistance mechanism was beyond this study.

Colistin resistance was associated in the majority of cases with OXA-48 which is now the most widespread type of carbapenemase in Croatia.[11] A few isolates from southern regions of Croatia (Dubrovnik and Split) were found to co-harbor KPC carbapenemases. The isolates positive for OXA-48 exhibited very low MICs of meropenem and imipenem with the majority of isolates being in the susceptible range. All except seven isolates co-harbored additional group 1 CTX-M β-lactamase associated with high level resistance to ESC and gentamicin. OXA-48 was probably carried by IncL plasmid responsible for horizontal spread of this important resistance determinant. Difficulties in transfer of plasmid from K. pneumoniae donor strains are likely due to the high molecular mass expected for the IncL plasmid identified in these strains. Because of this technical limitation, it was not possible to determine the location of blaOXA-48 genes. Four KPC producing organisms showed high level of resistance to all antibiotics except for sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim.

Croatia has a national surveillance system set in place and specific guidelines for the management of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae, along with the obligation to report them to the health authorities. Despite these measures we have seen an increase of OXA-48 producing organisms, similar to the situation in other European countries. However, there is no national surveillance programme for monitoring colistin resistance.

The production of ESBL, predominantly belonging to the CTX-M family, was associated with resistance to ESC. In this study the majority of OXA-48 positive organisms harbored ESBLs and attributable ESC resistance, which is in contrast with the previous study which analysed OXA-48 colistin susceptible K. pneumoniae.[11,12] ESBL positive isolates exhibited resistance to gentamicin and fluoroquinolones due to the additional aac and qnr genes usually located at the same plasmid. All isolates showed a high level of resistance to amoxicillin/clavulanate and piperacillin/tazobactam, which is consistent with both OXA-48 β-lactamase resistant to inhibitors and KPC which also efficiently hydrolyze penicillins. Almost half of the isolates were XDR, limiting the therapeutic options.

Based on resistance gene content, three clones were identified: a large cluster with OXA-48 positive isolates containing 39 isolates and two small clusters, one with KPC (4 isolates) and one with CTX-M-group 1 as the sole β-lactam resistance mechanism (two isolates), respectively. One single isolate harbored NDM-1 carbapenemase. OXA-48 exhibited variable MICs of carbapenems ranging from susceptibility to frank resistance. All except two OXA-48 positive isolates demonstrated resistance to ESC due to additional CTX-M β-lactamase and were classified as MDR. Four KPC and one NDM-1 producing organisms were XDR. Interestingly, colistin resistance in northern or middle regions of Croatia (Zagreb, Sisak and Karlovac) was associated with OXA-48 whereas in southern areas of Croatia (Split and Dubrovnik) with KPC. In other European countries colistin resistance was in the majority of cases linked to KPC carbapenemases, in contrast to our study where OXA-48 was the dominant carbapenem resistance determinant.[9,10] Colistin resistance in some centers such as Karlovac and Split reached an alarming rate of 7.9% and 9.8%, respectively.

The OXA-48 positive isolates exhibited variable MICs of imipenem and meropenem ranging from 0.5 to >128 mg/L making the phenotypic detection difficult and unreliable. All isolates showed reduced susceptibility to ertapenem in disk-diffusion test, which is used as screening method for carbapenemase production. Due to the very variable level of carbapenem resistance, microbiologists rely on the phenotypic tests. An important proportion of OXA-48 positive isolates exhibited resistance only to ertapenem, with MICs of imipenem and meropenem being in the susceptible or intermediate susceptible range. For that reason, laboratory detection of OXA-48 poses a serious challenge to clinical microbiologists. KPC and NDM positive organisms showed high level of resistance to almost all antibiotics and XDR phenotype. False negative Hodge and CIM tests observed in some isolates were linked solely to OXA-48 carbapenemase.

High variability of carbapenem MICs could be attributable to variable expression of blaOXA-48 genes. Surprisingly, the MICs of meropenem were higher than those of imipenem in the majority of isolates in spite of the fact that imipenem is, generally, better hydrolyzed by oxacillinases.

Part of the OXA-48 positive isolates were positive for IS1999 upstream of the blaOXA-48 gene which is responsible for the mobilization of blaOXA-48 genes and enhances the expression of the gene. Analysis of the flanking regions of blaOXA-48 gene revealed IS1R element between IS1999 and the OXA-48 encoding gene. ISEcp which mediates the mobility and expression of the blaCTX-M gene was found in only three strains, which could explain lack of transferability of cefotaxime resistance.

IncFIIs plasmid was dominant among isolates. In the previous studies it was associated with the spread of KPC carbapenemase, but in the present study it was found in isolates harboring OXA-48 and CTX-M β-lactamases. IncL/M was found in the NDM positive organism which is in concordance with the previous results. Similar types of plasmids were obtained in the previous studies on carbapenemases in Croatia.[11,12,13] Unlike in Italy, our KPC producing organisms did not harbor blaTEM-1 or blaOXA-9 genes.[9,10] The antibiotic susceptibilities were similar with high level of resistance to the majority of antibiotics, but our isolates were uniformly resistant to gentamicin in contrast to the Italian isolates reported. Regarding the virulence factors, production of β-hemolysins was linked to OXA-48 positivity whereas hyperviscosity was found only in one KPC producing organism. Both groups of isolates showed resistance to serum bactericidal activity allowing them to cause severe systemic infections such as bloodstream infections. However, septicemia was diagnosed in only two patients and in general, mortality rate was lower than expected concerning MDR or XDR phenotype. Ceftazidime/avibactam was shown to be associated with favorable therapeutic outcome. There was no association between the severity of infection or outcome and the presence of certain virulence traits.

Spread of carbapenemase producing K. pneumoniae was polyclonal, similarly as in the previous studies and probably mediated by horizontal spread of plasmids belonging to the same incompatibility group.[11,12,13] Polyclonal spread including various STs and PFGE patterns was also reported in Italy,[9,10] while in USA dissemination of colistin resistant K. pneumoniae was monoclonal.[8] However, some clonal similarity was observed between isolates from Karlovac and those from Zagreb and Sisak indicating a possible epidemiological link probably due to patient or staff transfer. Infection control measures were implemented and the outbreak in Karlovac was terminated. ST37 was previously reported among isolates from Croatia with different types of carbapenemases, indicating that the same isolate lineages can evolve and acquire different resistance traits. The strength of the study is detailed molecular analysis of additional resistance mechanisms such as ESBLs and carbapenemases and inclusion of multiple centers, but the limitation is that the mechanism of colistin resistance was not clarified and that the genotyping was done by an “old” method such as PFGE whereas MLST as the portable method enabling international comparisons of the isolates, was done for only one isolate. Future studies should employ whole genome sequencing to analyze the complete resistance and also virulence gene content of these successful isolates.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the study found a rapid spread of colistin-resistant K. pneumoniae in different geographic regions of Croatia, usually associated with OXA-48 and in a lesser extent with KPC or NDM carbapenemases. High diversity of additional resistance determinants associated with colistin resistance was noticed. Colistin resistance was detected not only in the hospital setting but also in the community indicating the dissemination of these important resistance determinants outside of the hospital setting. Plasmid-mediated colistin resistance was not identified in any of the strains, which is in concordance with other studies.[1,9,10]

The spread of colistin resistance determinants among outpatients is particularly raising concern pointing to the efflux of this important resistance determinant to the community and environment. Colistin has been extensively used in our hospitals during the last ten years, and the presence of colistin resistance among K. pneumoniae with different resistance phenotypes and genotypes isolated from different Croatian hospitals emphasizes the need for restricted use of colistin and early recognition of such strains. Monitoring the distribution and dissemination of emerging antibiotic resistance determinants is essential in order to enforce adequate control measures and to adjust antimicrobial therapy guidelines in various hospital settings.

Author Contributions

TT, MJ, SK contributed to: laboratory analysis (susceptibility testing, PCR, PFGE). SS, KN, AB, MK, MT, MBŠ contributed to: strain and data collection. JV contributed to: critical review of the manuscript. BB contributed to: experimental work and manuscript preparation. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was partly supported by Horizon 2020 project FAPIC (Fast Assay for Pathogen Identification and Characterisation), grant agreement ID: 634137 (funded under H2020-EU.3.1.3).

Conflicts of Interest

All authors – none to declare.

Ethical statement

Not necessary. The study was done on bacterial isolates and did not include human or animal subjects.

References

- Cannateli, A.; Giani, T.; D'Andrea, M.M.; et al. MgrB inactivation is a common mechanism of colistin resistance in KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae of clinical origin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 5696–5703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falagas, M.E.; Rafailidis, P.I.; Matthaiou, D.K. 2010. Resistance to polymyxins: mechanisms, frequency and treatment options. Drug Resist Updat. 2010, 13, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayol, A.; Poirel, L.; Brink, A.; Villegas, M.V.; Yilmaz, M.; Nordmann, P. 2014. Resistance to colistin associated with a single amino acid change in protein PmrB among Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates of worldwide origin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 4762–4766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayol, A.; Nordmann, P.; Brink, A.; Vilegas, M.V.; Dubois, V.; Poirel, L. High-level resistance to colistin mediated by various mutations in the crrB gene among carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017, 61, e01423–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordmann, P.; Poirel, L. Plasmid-mediated colistin resistance: an additional antibiotic resistance menace. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016, 22, 398–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.Y.; Wang, Y.; Walsh, T.R.; et al. Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: a microbiological and molecular biological study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016, 16, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Emergence of a novel mobile colistin resistance gene, mcr-8, in NDM-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2018, 7, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanovich, T.; Adams-Haduch, J.; Tian, G.B.; et al. Colistin-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC)-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae belonging to the international epidemic clone ST258. Clin Infect Dis. 2011, 53, 373–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, E.P.; Cervoni, M.; Bernardo, M.; et al. Molecular epidemiology and virulence profiles of colistin-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae blood isolates from the Hospital agency “Ospedale dei Colli”, Naples, Italy. Front Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mammina, C.; Bonura, C.; Di Bernardo, F.; et al. Ongoing spread of colistin-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in different wards of an acute general hospital, Italy, June to December 2011. Euro Surveill. 2012, 17, 20248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedenić, B.; Slade, M.; Žele-Starčević, L.; et al. Epidemic spread of OXA-48 beta-lactamase in Croatia. J Med Microbiol. 2018, 67, 1031–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedenić, B.; Sardelić, S.; Luxner, J.; et al. Molecular characterization of class B carbapenemases in advanced stage of dissemination and emergence of class D carbapenemases in Enterobacteriaceae from Croatia. Infect Genetic Evol. 2016, 43, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Onofrio, V.; Conzemius, R.; Varda-Brkić, D.; et al. Epidemiology of colistin-resistant, carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae and Acinetobacter baumannii in Croatia. Infect Genet Evol. 2020, 81, 104263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 26th ed.; CLSI supplement. M100-S; CLSI: Wayne, PA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Magiorakos, A.P.; Srinivasan, A.; Carey, R.B.; et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012, 18, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarlier, V.; Nicolas, M.H.; Fournier, G.; Philippon, A. Extended broad-spectrum β-lactamases conferring transferable resistance to newer β-lactam agents in Enterobacteriaceae: hospital prevalence and susceptibility patterns. Rev Infect Dis. 1988, 10, 867–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Lim, Y.S.; Yong, D.; Yum, J.H.; Chong, Y. Evaluation of the Hodge test and the imipenem-EDTA-double-disk synergy test for differentiating metallo-β-lactamase-producing isolates of Pseudomonas spp. and Acinetobacter spp. J Clin Microbiol. 2003, 41, 4623–4629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Zwaluw, K.; de Haan, A.; Pluister, G.N.; Bootsma, H.J.; de Neeling, A.J.; Schouls, L.M. The carbapenem inactivation method (CIM), a simple and low-cost alternative for the Carba NP test to assess phenotypic carbapenemase activity in gram-negative rods. PLoS One. 2015, 10, e0123690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elwell, L.P.; Falkow, S. The characterization of R plasmids and the detection of plasmid-specified genes. In Antibiotics in laboratory medicine, 2nd ed.; Lorian, V., Ed.; Williams and Wilkins: Baltimore, 1986; pp. 683–721. [Google Scholar]

- Nüesch-Inderbinen, M.T.; Hächler, H.; Kayser, F.H. Detection of genes coding for extended-spectrum SHV β-lactamases in clinical isolates by a molecular genetic method, and comparison with the E test. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1996, 15, 398–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arlet, G.; Brami, G.; Décrè, D.; et al. Molecular characterization by PCR-restriction fragment polymorphism of TEM beta-lactamases. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995, 134, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodford, N.; Ward, M.E.; Kaufmann, M.E.; et al. Community and hospital spread of Escherichia coli producing CTX-M extended-spectrum β-lactamases in the UK. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2004, 54, 735–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poirel, L.; Walsh, T.R.; Cuveiller, V.; Nordman, P. Multiplex PCR for detection of acquired carbapenemases genes. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011, 70, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carattoli, A.; Bertini, A.; Villa, L.; Falbo, V.; Hopkins, K.L.; Threlfall, E.J. Identification of plasmids by PCR-based replicon typing. J Microbiol Methods. 2005, 63, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufman, M.E. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. In Molecular bacteriology. Protocols and clinical applications, 1st ed.; Woodfor, N., Johnsons, A., Eds.; Humana Press Inc. Totowa: New York, 1998; pp. 33–51. [Google Scholar]

© GERMS 2021.