Abstract

Introduction: Tuberculosis (TB) is a communicable disease common worldwide. Influencing factors in TB outcomes include socio-demographics, as well as disease-related and treatment-related factors. This study aimed to analyze the prevalence trends of unsuccessful treatment outcomes in Southern Tunisia during 1995-2016 and to identify their risk factors. Methods: This was a retrospective study including all notified cases from the tuberculosis center reporting registers in Southern Tunisia between 1995 and 2016. Results: Overall, 2771 TB cases were notified. Unsuccessful treatment outcomes were noted in 196 cases (7%). Unsuccessful treatment outcome was associated with male gender (OR = 1.4; p = 0.023), elderly status (≥60 years, OR = 2.3; p < 0.001), joints and bones site (OR = 2.2; p = 0.002) as well as meningeal involvement (OR = 2.4; p = 0.023). Lymph node (OR = 0.4; p < 0.001) and therapy duration ≥6 months (OR = 0.003; p < 0.001) were statistically associated with lower rate of unsuccessful outcome. Multivariate regression analysis showed that elderly status (AOR = 2.3; p < 0.001), meningeal involvement (AOR = 2.2; p < 0.027) as well as bone and joints involvements (AOR = 2; p = 0.027) were independently associated with unsuccessful outcome. Trends analysis showed that the case-fatality rate significantly increased from 1995 to 2016 (Rho = 0.4; p = 0.032). Conclusions: The high prevalence of unsuccessful outcome suggested important inadequacies in the TB program. An effective strategy to improve therapeutic education of patients with TB is therefore urgently needed.

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) is a communicable disease common worldwide and a leading cause of death worldwide. It is a public health problem because of its high morbidity and mortality.[1] The latest international target of the World Health Organization (WHO) has been set for the period 2015-2035 to achieve a 95% reduction in TB deaths and 90% reduction in TB incidence rate.[2] Death is the worst outcome of a patient with tuberculosis. Nevertheless, other adverse treatment outcomes such as failure can aid disease spread and the development of drug resistance. Influencing factors in TB outcomes include socio-demographics such as gender and age, as well as disease-related, treatment-related factors and adherence to the long course of TB treatment.[3]

According to the WHO Global TB Report 2018, Tunisia is an intermediate endemic country with a recorded incidence of 29/100,000 population in 2017.[4] The trend, which had been decreasing for several years, has been reversed since 2003 and there has been a resurgence of the disease. Tuberculosis is a reportable disease in our country and since 2010, the TB surveillance system has been based on the registration of cases for treatment. The National Tuberculosis Control Program (NTCP) covers the entire territory of Tunisia through its integration into basic health structures. This program is based on the directly observed therapy (DOT) strategy that has been 100% widespread throughout the country since 1999. Also, the NTCP provides free treatment for patients with TB, screening for contacts and compulsory vaccination from birth with the BCG vaccine. Side effects of treatment are monitored monthly by a clinical examination and when necessary through biological exploration. The combined form of treatment tablets has been introduced since 2009 in Tunisia to ameliorate adherence to treatment and to control unsuccessful outcome. The objective of the NTCP is to reduce morbidity and mortality due to tuberculosis. The incidence of mortality was estimated at 2.9 per 100,000 population in 2017.[4] Given that mortality remains high, a deep understanding of predictors of poor outcomes in treatment of TB allows policy makers to plan therapeutic and preventive strategies focused on high-risk groups. Thus, identifying the prevalence of unsuccessful treatment outcome and its associated factors is important to achieve Sustainable Development Goals of the WHO. Goals are pushing down global TB incidence rates from an annual decline of 2% in 2015 to 10% by 2025 and reducing the proportion of people with TB who die from the disease from 15% in 2015 to 5% by 2025.[2] In Southern Tunisia, a highly TB endemic region, data of TB epidemiological and prognostic profiles are scarce and disparate. Major challenges to control TB in Tunisia include poor primary healthcare infrastructure, mainly in rural areas, unregulated private healthcare leading to widespread irrational use of first line and second-line anti-TB drugs and lack of adherence to treatment. In this context, this study aimed to analyze the prevalence trends of unsuccessful treatment outcome in Southern Tunisia, during 1995-2016 and to identify their risk factors.

Methods

Outline of the patient registry

Tuberculosis is a mandatory reportable disease in Tunisia. Declaration of cases is done immediately to the regional health directorate using a standardized reporting card which contains socio-demographics data such as gender, age, origin, as well as type and location of TB, treatment regimen, duration of treatment and treatment outcomes.

Data collection

We retrospectively collected data from the tuberculosis center reporting registers (TCRR) in Southern Tunisia between 1995 and 2016. This center was established as an integral part of the national TB control program since 1978. Data were collected using a pre-defined fact sheet including all data in the reporting card.

Study population

This study included all new cases of TB of any age registered between 1995 and 2016. All patients with TB whose diagnosis was made in either public or private health facilities during the study period were included. The diagnosis was made based on bacteriological documentation, failing on histological arguments, radiological and clinical signs, or adequate response to anti-tubercular treatment. Then patients were notified in the TCRR for additional care.

Case definition: tuberculosis treatment outcomes

Patients were classified according to the WHO Guidelines as follows: Treatment outcomes were classified into unsuccessful in case of TB death (a patient with TB who dies for any reason before starting or during the course of treatment) or lost to follow-up (a patient with TB who did not start treatment or whose treatment was interrupted for 2 consecutive months or more), or treatment failed (a patient with TB whose sputum smear or culture is positive at month 5 or later during treatment).[5] As for successful treatment, it was defined as cure or treatment completed.[5]

Statistical analysis

The description of the categorical variables was carried out by the determination of the absolute and relative frequencies. Continuous variables were determined by means and standard deviations or by medians and interquartile range (IQR) according to the distribution of the variable.

We used Chi-square test and Fisher test to compare two frequencies and we determined for each association the odds ratio (OR) and its 95% confidence interval (95%CI). To define the independent risk factors predictive of unsuccessful outcome, we carried out a multivariate analysis using logistic backward stepwise regression (adjusted OR [AOR]; 95%CI; p). We used Spearman's correlation coefficient (Rho) to analyze TB chronological trends. The difference between groups was considered significant when p<0.05.

Ethical considerations

Ethical considerations were conducted according to The Declaration of Helsinki. Ethics approval was not applicable for this study. Data were retrospectively collected from registers of TB declaration in the regional health directorate without patient contact. These data were collected with confidentially and anonymity. This study did not involve human beings or experiments.

Results

Patients’ characteristics

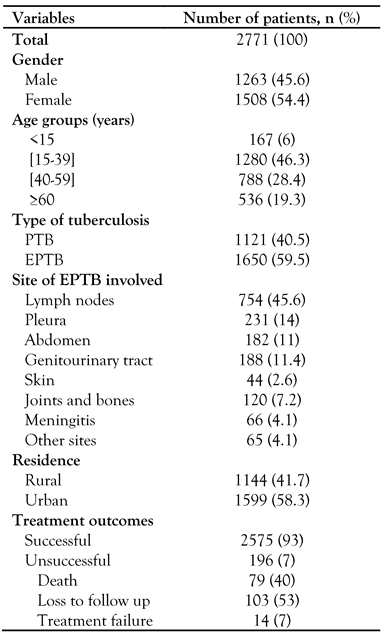

Overall, 2771 TB cases were notified. The most frequent age group was 15-39 years (46.2%). The median age was 38 years (IQR 25-55 years). There were 1508 males (54.4%), with a sex ratio (male/female) of 1.19. The successful outcome rate was 93%. Unsuccessful treatment outcomes were notified in 196 cases (7%). During the study period, we noted that the loss to follow-up rate was 3.5% and the death rate was 2.9%. Pulmonary TB (PTB) was noted in 1650 cases (59.5%). From 1221 cases (40.5%) of extra-pulmonary tuberculosis (EPTB), lymph node TB was the most common form (754 cases; 45.6%) followed by pleural TB (231 cases; 14%) and genitourinary TB (188 cases; 11.4%) – Table 1.

Table 1.

Patients’ characteristics.

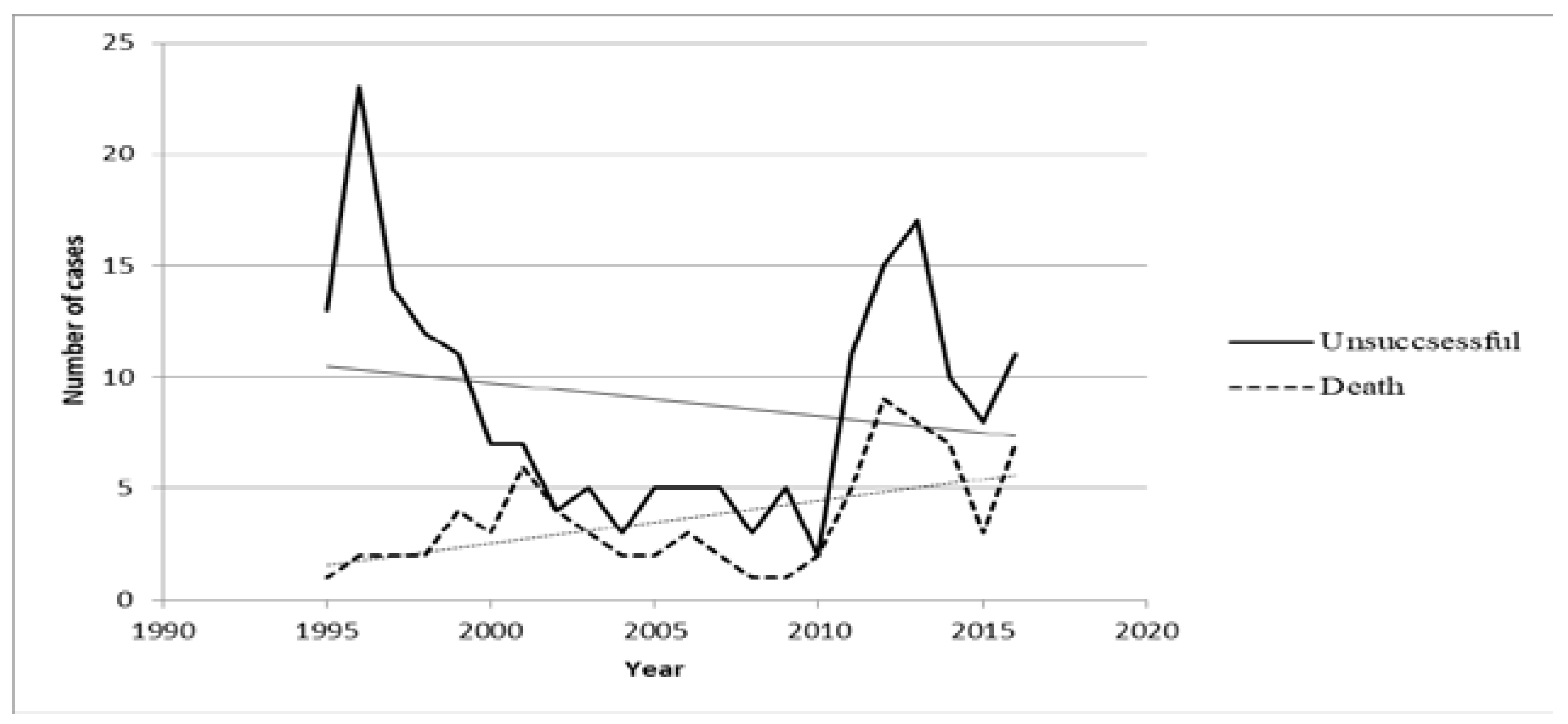

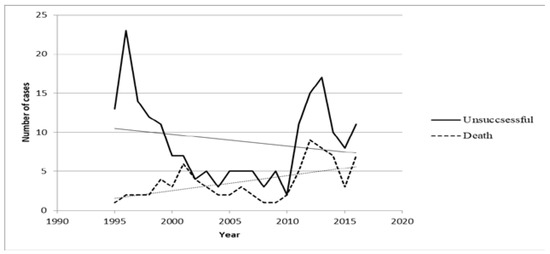

Trends analysis showed that the number of cases with unsuccessful outcome decreased from 1995 to 2016 (Rho=-0.14; p=0.520) and that the TB lethality rate significantly increased from 1995 to 2016 (Rho=0.4; p=0.032) – Figure 1. However, trends analysis showed that the number of cases with severe forms of TB did not increase from 1995 to 2016 (Rho=-0.16; p=0.480).

Figure 1.

Chronological trends of unsuccessful outcomes and deaths between 1995-2016.

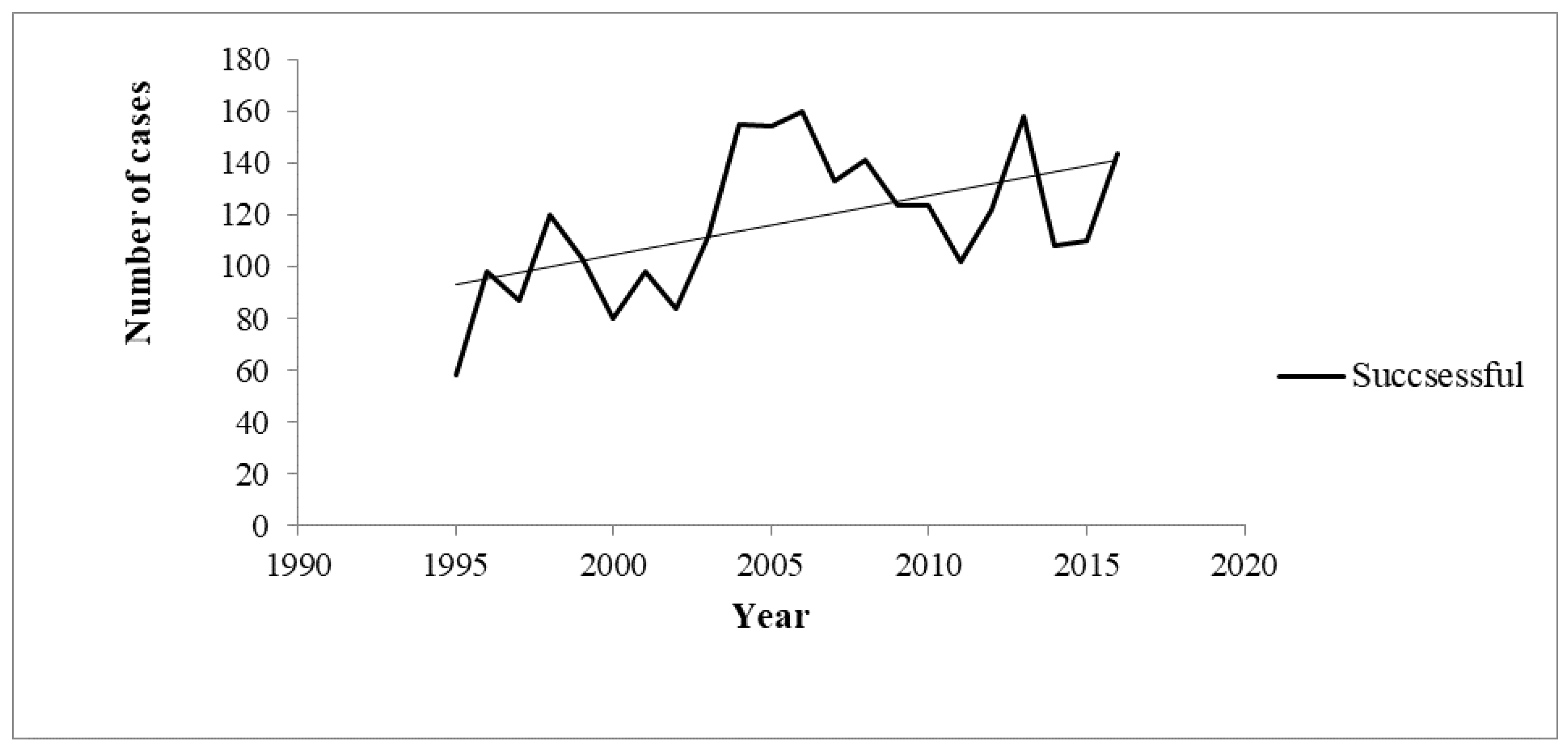

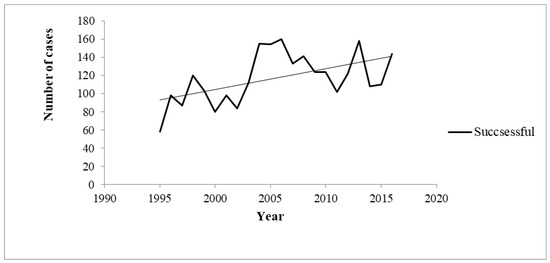

On the other hand, the chronological trend of the number of cases with successful outcome increased from 1995 to 2016 (Rho=0.4; p=0.032) – Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Chronological trends of successful outcomes between 1995 and 2016.

Predictors of unsuccessful outcomes

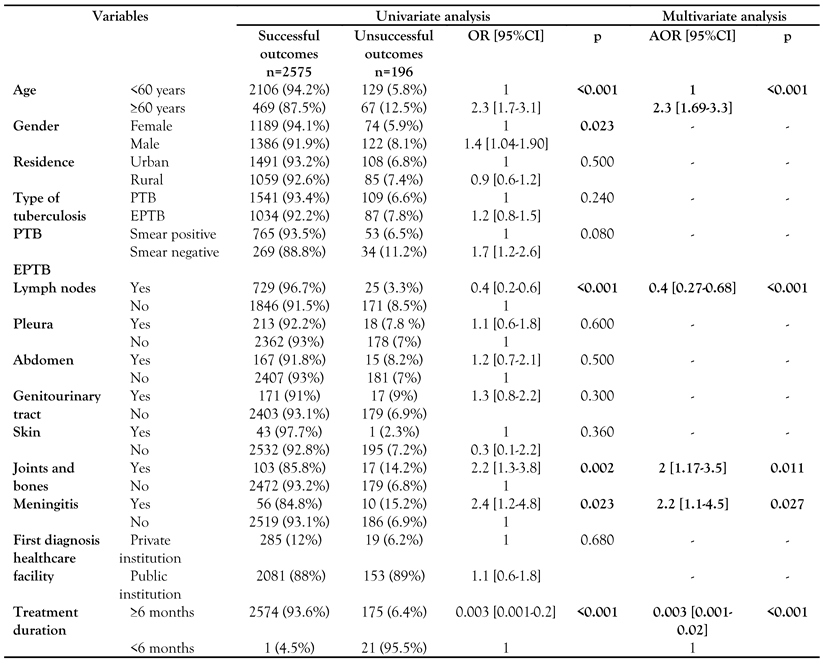

Unsuccessful outcome was associated with male gender (OR=1.4; p=0.023), elderly status (≥60 years, OR=2.3; p<0.001), joints and bones site TB (OR=2.2; p=0.002) as well as meningeal involvement (OR=2.4; p=0.023). Lymph node (OR=0.4; p<0.001) and therapy duration ≥6 months (OR=0.003; p<0.001) were statistically associated with a lower rate of unsuccessful outcome (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of treatment outcomes in patients with tuberculosis in Southern Tunisia (1995-2016).

Multivariate regression analysis showed that elderly age (AOR=2.3; p<0.001), meningeal involvement (AOR=2.2; p<0.027) as well as bone and joints involvement (AOR=2; p=0.027) were independently associated with unsuccessful outcome. On the other hand, lymph node (AOR=0.4); p<0.001) and therapy duration >6 months (AOR=0.003; p<0.001) were independently associated with a lower rate of unsuccessful outcome (Table 2).

Discussion

This original study highlighted the epidemiological profile and treatment outcomes of patients with TB in Southern Tunisia. It was a long-term study for two decades, covering a time span of 22 years, which made the results more precise and fruitful.

In this study, the successful treatment outcome rate was higher than the WHO rate reported in 2016. The latest treatment outcome data for new cases showed a global treatment success rate of 82% in 2016.[4] Otherwise, the rate of unsuccessful outcomes of TB treatment was 7%. It was however, lower than that of Northwestern Ethiopia (12.9%).[3] Reasons for these discrepancies may be attributed to the methodology with respect to sample size. It could be also explained by the regular follow up in the TB center in Southern Tunisia. The main unsuccessful treatment outcome was “lost to follow up”. Otherwise, it was higher than other rates reported from Northwestern Ethiopia (2.4%).[3] Feeling better after initiation of treatment could be an explanation for the early loss to follow up.[6,7] Moreover, poor knowledge on TB was cited as a predictor of loss to follow up.[6,8,9] Also, unawareness of the possibility of cure may encourage loss to follow-up.[8,10] Therefore, adequate patient education at initiation of treatment enhancing on returning to consultation on the scheduled date can increase the compliance to treatment. Health education could be an effective strategy that was adopted from many countries to ameliorate the prognosis.[6,11,12] In fact, nurses play a key role in the TB control strategy. It has been reported that home visits performed by nurses enable an interpersonal contact, which allows the identification of patients' needs and difficulties.[13]

Unsuccessful outcome for patients with TB was associated with male gender. Similarly, previous studies showed that male gender can be a risk factor for non-compliance to TB treatment.[6] In Morocco, which is a country sharing similar geographical and demographic characteristics with Tunisia, a recent study showed that male gender is a risk of failure, loss to follow up, or treatment relapse (OR=2.29).[14] This gender disparity might be due to economic reasons. Men are the main contributors to the family income, which makes it difficult to afford to take time off for medical visits. Travel time to and from the clinic represents indeed time absent from work and potentially less money earned.[15] Another explanation for this association could also be tobacco smoking. Prevalence of tobacco use in males is higher than in women. In fact, studies have shown associations between tobacco use and failure to complete the treatment.[7,16]

Similar to other studies, older age was associated with unsuccessful outcome in our study. In fact, having an age >60 years can favor death and loss to follow up.[16,17] In India, 14% of all patients with TB were older and had a 38% higher risk of unfavorable treatment outcome as compared to all other patients with TB.[18] Another study reported a high rate of treatment loss to follow up in the elderly.[19] It could be explained by the poor memory of appointment dates, comorbidities and the inability to visit the clinic due to the absence of another family member to accompany them.[18] Treatment loss to follow up in the elderly may be lowered by providing quality geriatric health services.

As opposed to our study, previous studies showed that residence area is an important determinant for treatment compliance and outcome. In Southern Ethiopia, a study showed that patients from rural areas were 1.5 times more likely to develop unsuccessful outcome than those from urban areas (AOR=1.5).[20] Patients from rural areas probably are less aware of TB treatment, and there is a long distance between their homes and the treatment centers.[21] Regarding the site of EPTB, patients with meningeal TB were more likely to develop unsuccessful outcome. Similar findings were reported from many other studies.[22] This is probably due to the increased chances of misdiagnosis with a long delay in starting treatment, long treatment duration, complications from which patients suffered due to meningeal TB and drug resistance.[23] In contrast, patients with lymph node TB had a lower rate of unsuccessful outcome. Tuberculosis adenitis is recommended to be managed as a systemic disease with anti-tuberculosis medication.[24]

Study limitations

This original study highlighted the treatment outcomes and adherence to TB treatment in Southern Tunisia, but it had some limitations. This was a retrospective study based only on data available in the TB center reporting registers. Some of the sampled patients lost to follow up in our study were not traced, whereas others might have died without notification to the center. Thus, prospective, and multi-center studies would improve on these limitations.

Considerations for the future

To improve adherence to treatment and reduce the rate of treatment failure and mortality, remedial measures must be introduced to involve more doctors who are the gold standard in the implementation of the national program. Good registration practices are needed to ensure and support effective patient outcomes. The case registration and notification system are part of the health information management system. It includes detailed forms on patients, which are compiled at the site of care and summarized in laboratory records of medical centers. The system for patient registration and notification allows systematic evaluation of disease evolution and treatment outcomes, and monitoring the performance of the entire program (cohort analysis).

Conclusions

The implementation of multidimensional evidence-based practices was associated with a reduction in SSIs following knee and hip arthroplasty procedures. Achieving a prolonged and continuous implementation of this approach is needed to maintain improved outcomes.

Author Contributions

MBH, HBA, MK, HF, JD and MBJ designed and supervised the study and drafted the manuscript. MBH, HBA, MK, FH, FS and TBJ collected the data. MBH, HBA, MK, MaBJ, MT and MBJ conducted the statistical analyses and drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

None to declare.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors – none to declare.

References

- World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2017. Available online: http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/ (accessed on 20 April 2019).

- World Health Organization. WHO end TB strategy. Available online: https://www.who.int/tb/post2015_strategy/en/ (accessed on 20 April 2019).

- Melese, A.; Zeleke, B.; Ewnete, B. Treatment outcome and associated factors among tuberculosis patients in Debre Tabor, Northwestern Ethiopia: a retrospective study. Tuberc Res Treat. 2016, 2016, 1354356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2019. Available online: http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/ (accessed on 28 February 2019).

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for treatment of tuberculosis. Available online: https://www.who.int/tb/publications/2010/9789241547833/en/ (accessed on 28 February 2019).

- Tachfouti, N.; Slama, K.; Berraho, M.; et al. Determinants of tuberculosis treatment default in Morocco: results from a national cohort study. Pan Afr Med J. 2013, 14, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaiswal, A.; Singh, V.; Ogden, J.A.; et al. Adherence to tuberculosis treatment: lessons from the urban setting of Delhi, India. Trop Med Int Health. 2003, 8, 625–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tola, H.H.; Tol, A.; Shojaeizadeh, D.; Garmaroudi, G. Tuberculosis treatment non-adherence and lost to follow up among TB patients with or without HIV in developing countries: a systematic review. Iran J Public Health. 2015, 44, 1-11. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Slama, K.; Tachfouti, N.; Obtel, M.; Nejjari, C. Factors associated with treatment default by tuberculosis patients in Fez, Morocco. East Mediterr Health J. 2013, 19, 687–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oblitas, F.Y.; Loncharich, N.; Salazar, M.E.; David, H.M.; Silva, I.; Velásquez, D. Nursings role in tuberculosis control: a discussion from the perspective of equity. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2010, 18, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis control: surveillance, planning, financing: WHO report 2005. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/144 569/9241562919_eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 5 March 2019).

- Aït-Khaled, N.; Alarcón, E.; Armengol, R.; et al. Prise en charge de la tuberculose. Guide des éléments essentiels pour une bonne pratique, 6ème édition; Union Internationale Contre la Tuberculose et les Maladies Respiratoires (L'union): Paris, 2010; p. 64. [Google Scholar]

- Ministério Da Saúde. Manual de recomendações para o controle da tuberculose no Brasil. Available online: http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/manual_rec omendacoes_controle_tuberculose_brasil.pdf (accessed on 6 March 2019).

- Dooley, K.E.; Lahlou, O.; Ghali, I.; et al. Risk factors for tuberculosis treatment failure, default, or relapse and outcomes of retreatment in Morocco. BMC Public Health. 2011, 11, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolappan, C.; Subramani, R.; Karunakaran, K.; Narayanan, P.R. Mortality of tuberculosis patients in Chennai, India. Bull World Health Organ. 2006, 84, 555–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naidoo, P.; Peltzer, K.; Louw, J.; Matseke, G.; McHunu, G.; Tutshana, B. Predictors of tuberculosis (TB) and antiretroviral (ARV) medication non-adherence in public primary care patients in South Africa: a cross sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2013, 13, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gust, D.A.; Mosimaneotsile, B.; Mathebula, U.; et al. Risk factors for non-adherence and loss to follow-up in a three-year clinical trial in Botswana. PLoS One. 2011, 6, e18435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ananthakrishnan, R.; Kumar, K.; Ganesh, M.; et al. The profile and treatment outcomes of the older (aged 60 years and above) tuberculosis patients in Tamilnadu, South India. PLoS One. 2013, 8, e67288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oshi, D.C.; Oshi, S.N.; Alobu, I.; Ukwaja, K.N. Profile and treatment outcomes of tuberculosis in the elderly in southeastern Nigeria, 2011-2012. PLoS One. 2014, 9, e111910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dale, D.; Nega, D.; Yimam, B.; Ali, E. Predictors of poor tuberculosis treatment outcome at Arba Minch General Hospital, Southern Ethiopia: a case-control study. J Tuberc Ther. 2017, 2, 110. [Google Scholar]

- Belo, M.T.; Luiz, R.R.; Teixeira, E.G.; Hanson, C.; Trajman, A. Tuberculosis treatment outcomes and socio-economic status: a prospective study in Duque de Caxias, Brazil. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011, 15, 978–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherian, J.J.; Lobo, I.; Sukhlecha, A.; et al. Treatment outcome of extrapulmonary tuberculosis under Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme. Indian J Tuberc. 2017, 64, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huo, Y.; Zhan, Y.; Liu, G.; Wu, H. Tuberculosis meningitis: early diagnosis and treatment with clinical analysis of 180 patients. Radiol Infect Dis. 2019, 6, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, P.R.; Janmeja, A.K. Tuberculous lymphadenitis. J Assoc Physicians India. 2009, 57, 585–590. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

© GERMS 2021.