Across Regions: Are Most COVID-19 Deaths Above or Below Life Expectancy?

Abstract

Introduction

Methods

Assessing reported COVID-19 deaths: above and below life expectancy

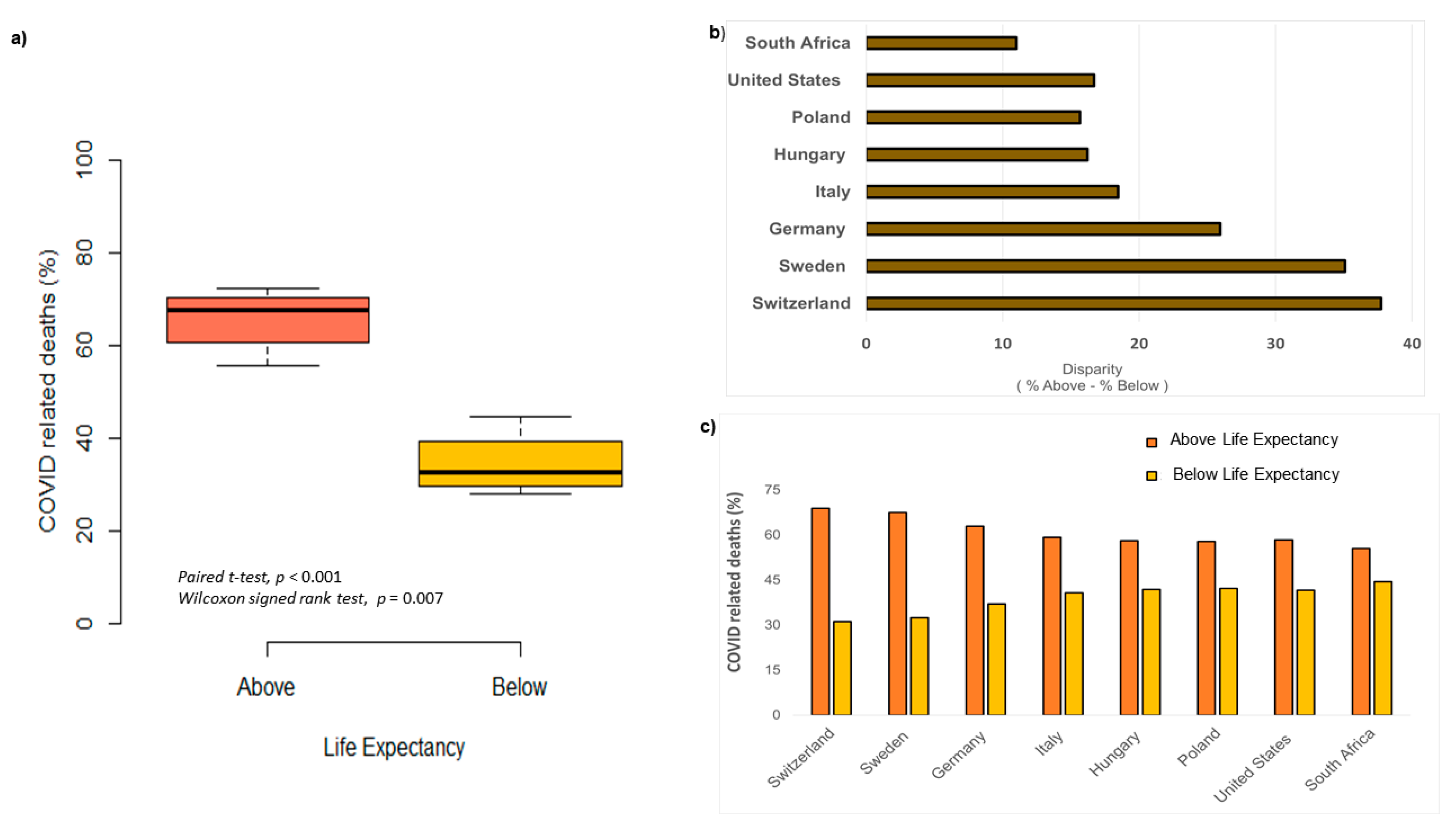

Analysis

Results

Discussion

Pandemics vary in targeted age class, but can they affect fitness?

Can variation in COVID-19 deaths be explained by regional differences?

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of interest

References

- Mann, R.; Perisetti, A.; Gajendran, M.; Gandhi, Z.; Umapathy, C.; Goyal, H. Clinical characteristics, diagnosis, and treatment of major coronavirus outbreaks. Front Med (Lausanne) 2020, 7, 581521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.D.; Harris, C.; Cain, J.K.; Hummer, C.; Goyal, H.; Perisetti, A. Pulmonary and extra-pulmonary clinical manifestations of COVID-19. Front Med (Lausanne) 2020, 7, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascella, M.; Rajnik, M.; Cuomo, A.; Dulebohn, S.C.; Di Napoli, R. Features, evaluation, and treatment of coronavirus (COVID-19). In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mandhana, N.; Myo, M. Pandemic crushes garment industry, the developing world’s path out of poverty. Wall Str. J. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Coro, G. A global-scale ecological niche model to predict SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus infection rate. Ecol Modell 2020, 431, 109187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogen, Y. Assessing nitrogen dioxide (NO2) levels as a contributing factor to coronavirus (COVID-19) fatality. Sci Total Environ 2020, 726, 138605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEvedy, C. The bubonic plague. Sci Am 1988, 258, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radusin, M. The Spanish flu—Part II: The second and third wave. Vojnosanit Pregl 2012, 69, 917–927. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The Global HIV/AIDS pandemic, 2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2006, 55, 841–844. [Google Scholar]

- Preston, S.H. American longevity: Past, present, and future. Cent. Policy Res. 1996, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gorina, Y.; Hoyert, D.; Lentzner, H.; Goulding, M. Trends in causes of death among older persons in the United States. Aging Trends 2005, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucman, G. Global wealth inequality. Annu Rev Econ 2019, 11, 109–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerman, R.I.; Yitzhaki, S. A note on the calculation and interpretation of the Gini index. Econ Lett 1984, 15, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Antiga, L. Coronaviruses and immunosuppressed patients: The facts during the third epidemic. Liver Transpl 2020, 26, 832–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, P.; Yang, X.L.; Wang, X.G.; et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 2020, 579, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer, Z. Poverty, wealth inequality and health among older adults in rural Cambodia. Soc Sci Med 2008, 66, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Administration for Community Living. 2019 profile of older Americans. 2020. Available online: https://acl.gov/sites/default/files/Aging%20and%20Disability%20in%20America/2019ProfileOlderAmericans508.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2020).

- Borak, J. Airborne transmission of COVID-19. Occup Med (Lond) 2020, 70, 297–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Zhang, B.; Lu, J.; et al. Characteristics of household transmission of COVID-19. Clin Infect Dis 2020, 71, 1943–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhadra, A.; Mukherjee, A.; Sarkar, K. Impact of population density on COVID-19 infected and mortality rate in India. Model Earth Syst Environ. 2020, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawood, F.S.; Iuliano, A.D.; Reed, C.; et al. Estimated global mortality associated with the first 12 months of 2009 pandemic influenza A H1N1 virus circulation: A modelling study. Lancet Infect Dis 2012, 12, 687–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliabadi, A.A.; Rogak, S.N.; Bartlett, K.H.; Green, S.I. Preventing airborne disease transmission: Review of methods for ventilation design in health care facilities. Adv Prev Med 2011, 2011, 124064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowell, G.; Nishiura, H. Transmission dynamics and control of Ebola virus disease (EVD): A review. BMC Med 2014, 12, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, J.C. Similarity is not enough: Tipping points of Ebola Zaire mortalities. Physica A: Stat Mech Appl 2015, 427, 277–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. J Sustain Tour 2020, 29, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Duan, H.J.; Chen, H.Y.; et al. Age and Ebola viral load correlate with mortality and survival time in 288 Ebola virus disease patients. Int J Infect Dis 2016, 42, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopel, J.; Perisetti, A.; Roghani, A.; Aziz, M.; Gajendran, M.; Goyal, H. Racial and gender-based differences in COVID-19. Front Public Health 2020, 8, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Economist. Tracking COVID-19 Excess Deaths Across Countries. 2020. Available online: https://www.economist.com/graphic- detail/coronavirus-excess-deaths-tracker (accessed on 1 August 2020).

- Center for Disease Control, National Vital Statistics System. U.S. Mortality Data Files, 1987–2013. Available online: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data_access/vitalstatsonline.htm (accessed on 1 August 2020).

- Ejaz, H.; Alsrhani, A.; Zafar, A.; et al. COVID-19 and comorbidities: Deleterious impact on infected patients. J Infect Public Health 2020, 13, 1833–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster, P.; Forster, L.; Renfrew, C.; Forster, M. Phylogenetic network analysis of SARS-CoV-2 genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2020, 117, 9241–9243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surleac, M.; Banica, L.; Casangiu, C.; et al. Molecular epidemiology analysis of SARS-CoV-2 strains circulating in Romania during the first months of the pandemic. Life (Basel) 2020, 10, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavian, C.; Pond, S.K.; Marini, S.; et al. Sampling bias and incorrect rooting make phylogenetic network tracing of SARS-COV-2 infections unreliable. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2020, 117, 12522–12523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brufsky, A.; Lotze, M.T. Ratcheting down the virulence of SARS-CoV-2 in the COVID-19 pandemic. J Med Virol 2020, 92, 2379–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The world Factbook. Country Comparisons: Gini Index Coefficient—Distribution of Family Income. 2020. Available online: https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/field/gini- index-coefficient-distribution-of-family-income/country- comparison (accessed on 1 August 2020).

- Junaid, K.; Ejaz, H.; Abdalla, A.E.; et al. Effective immune functions of micronutrients against SARS-CoV-2. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Country | Life Expectancy |

|---|---|

| Sweden | ~80 |

| Switzerland | ~80 |

| Germany | ~80 |

| Italy | ~80 |

| Hungary | ~75 |

| Poland | ~75 |

| United States | ~75 |

| South Africa | ~60 |

© GERMS 2025.

Share and Cite

Malik, R.J. Across Regions: Are Most COVID-19 Deaths Above or Below Life Expectancy? Germs 2021, 11, 59-65. https://doi.org/10.18683/germs.2021.1241

Malik RJ. Across Regions: Are Most COVID-19 Deaths Above or Below Life Expectancy? Germs. 2021; 11(1):59-65. https://doi.org/10.18683/germs.2021.1241

Chicago/Turabian StyleMalik, Rondy J. 2021. "Across Regions: Are Most COVID-19 Deaths Above or Below Life Expectancy?" Germs 11, no. 1: 59-65. https://doi.org/10.18683/germs.2021.1241

APA StyleMalik, R. J. (2021). Across Regions: Are Most COVID-19 Deaths Above or Below Life Expectancy? Germs, 11(1), 59-65. https://doi.org/10.18683/germs.2021.1241