Numerical Investigation on Rotational Cutting of Coal Seam by Single Cutting Pick

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Principles of the SPH Algorithm and Model Construction

2.1. Numerical Approximation Principle of SPH

2.2. Governing Equation

2.3. Constitutive Model

3. Rock Failure Model and Numerical Implementation

3.1. Shear Failure Model

3.2. Tension Failure Model

- (1)

- If or , the stress state is elastic, and no plastic correction is required.

- (2)

- If and , the stress state is plastic and must be corrected through stress adjustment.

4. Results and Discussion

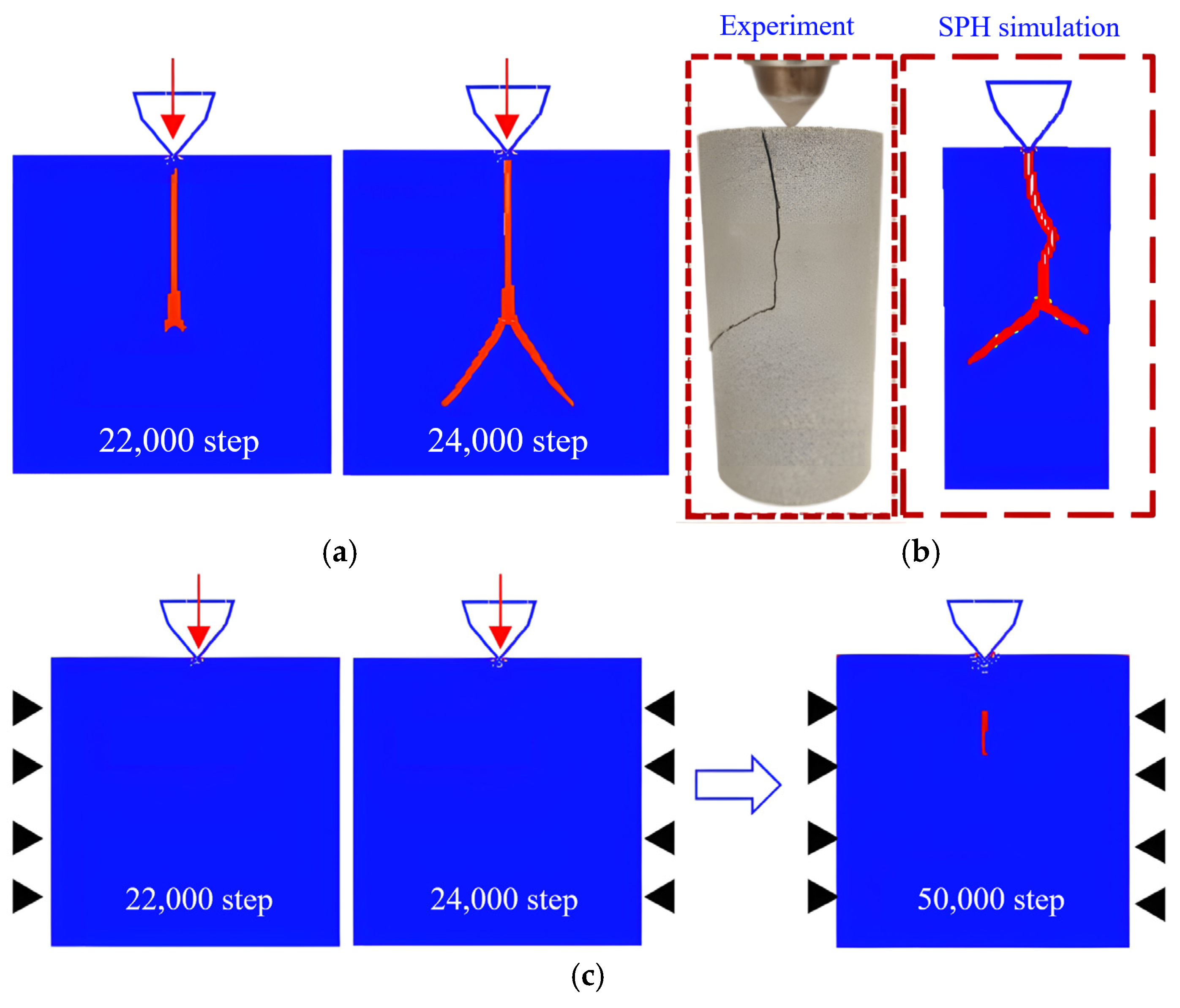

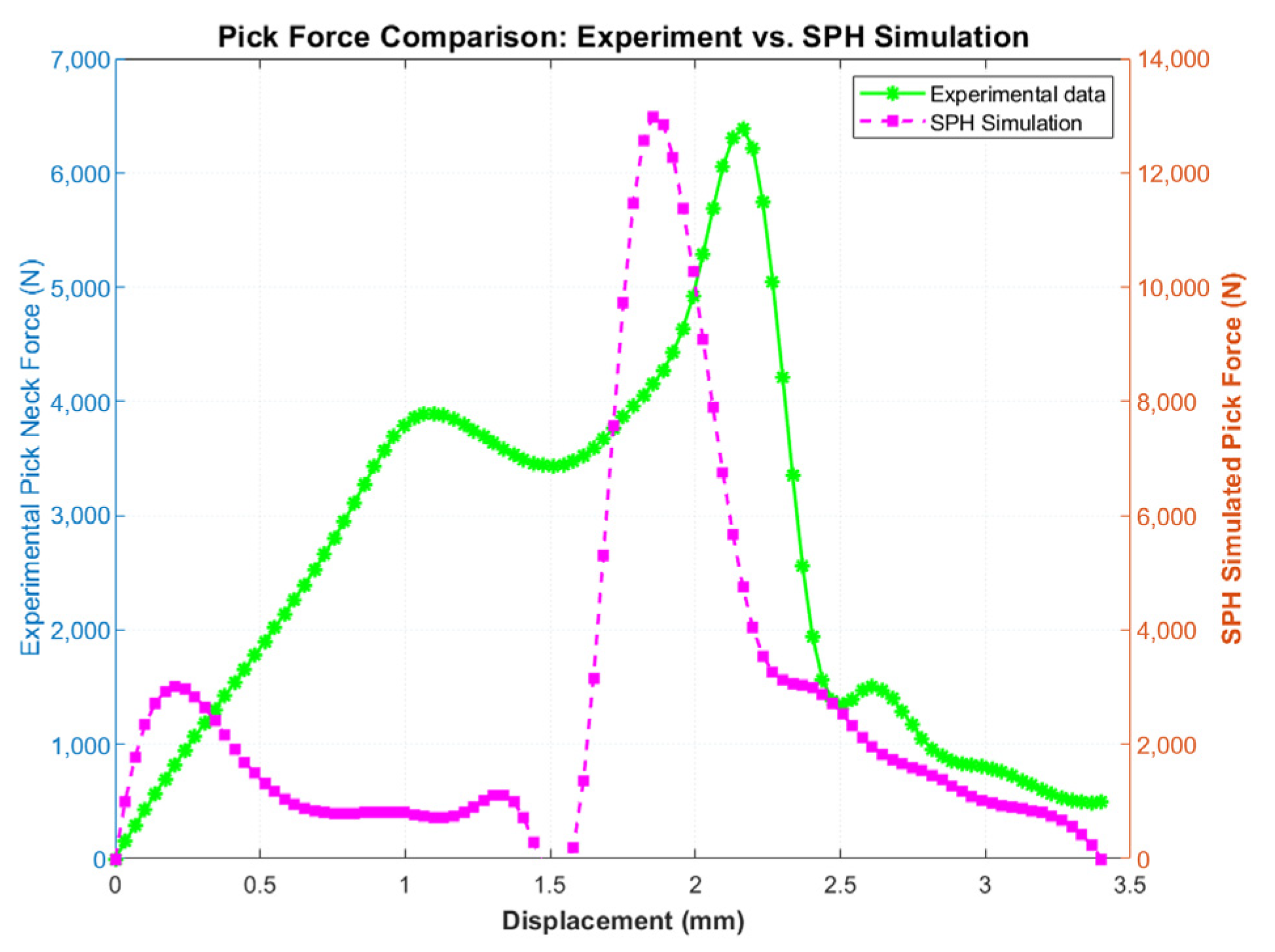

4.1. Verification of Rock Fracture and Damage Simulation

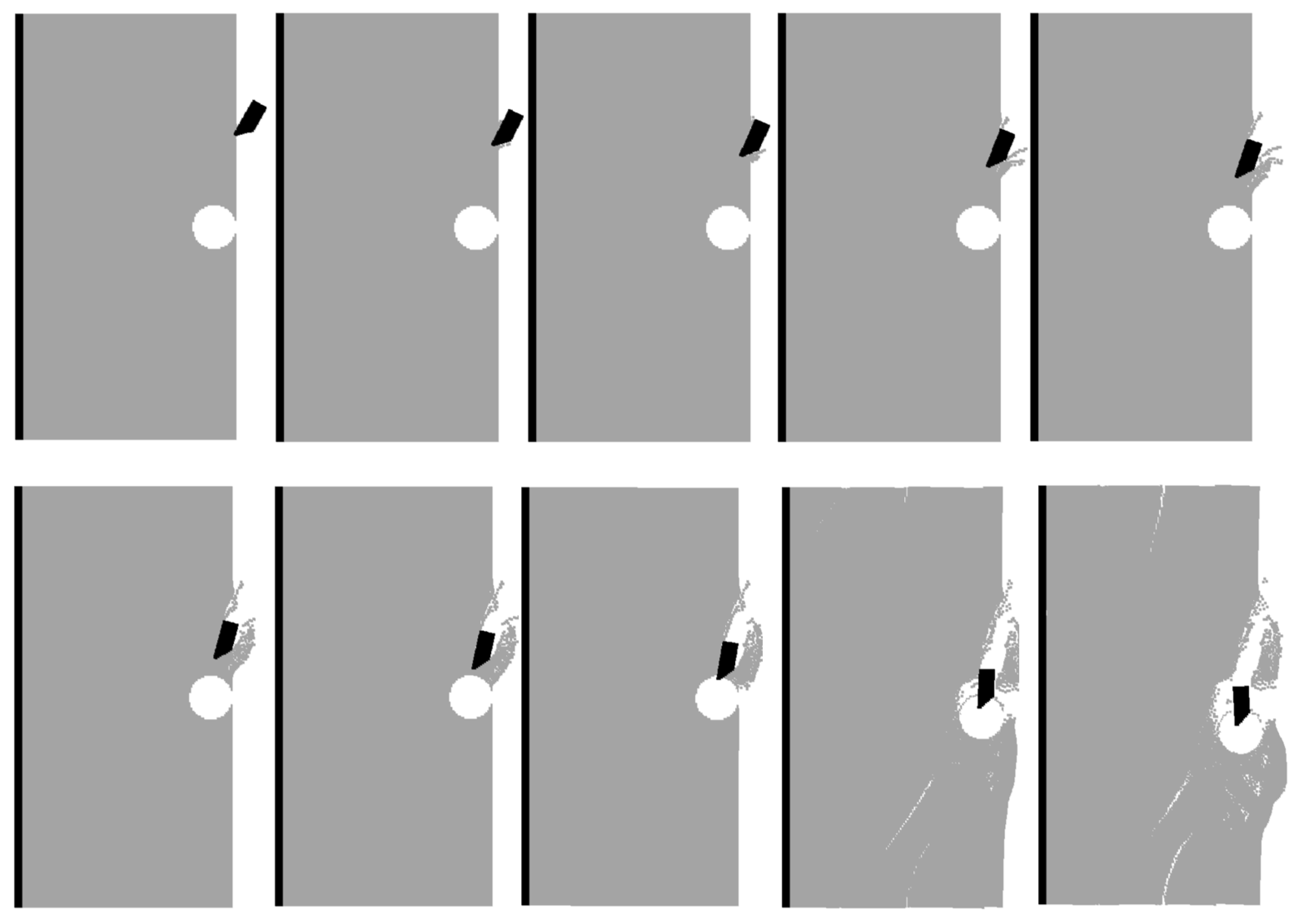

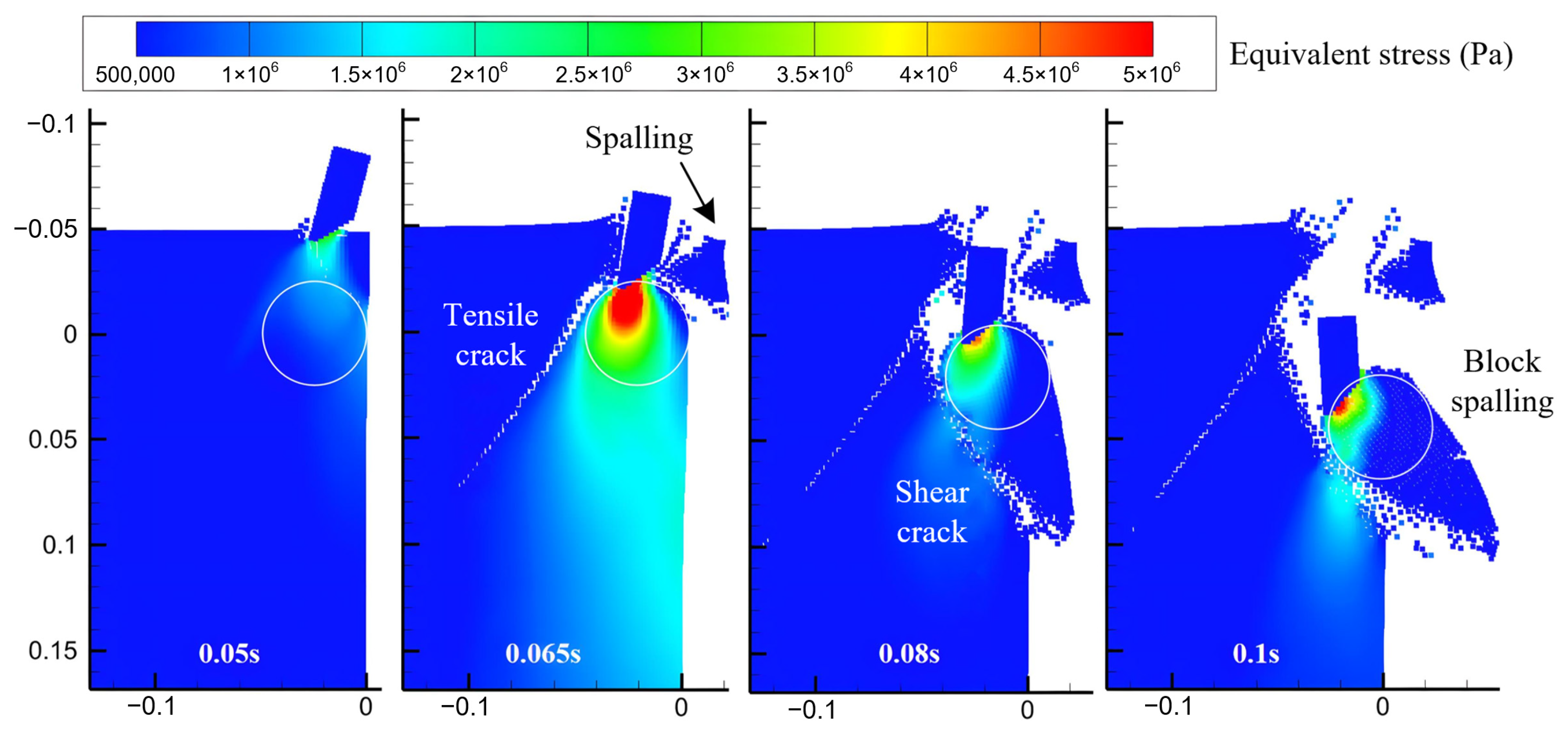

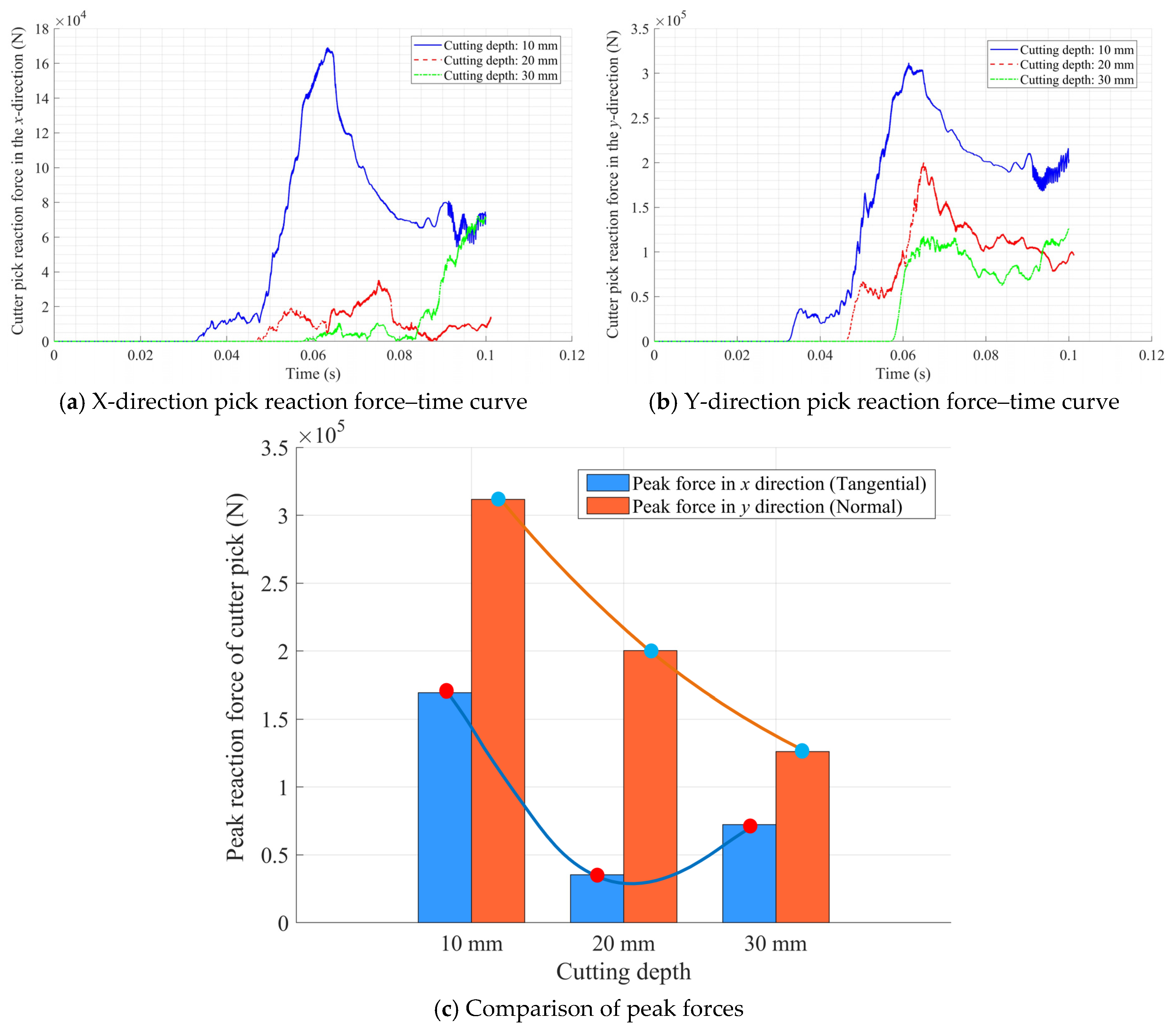

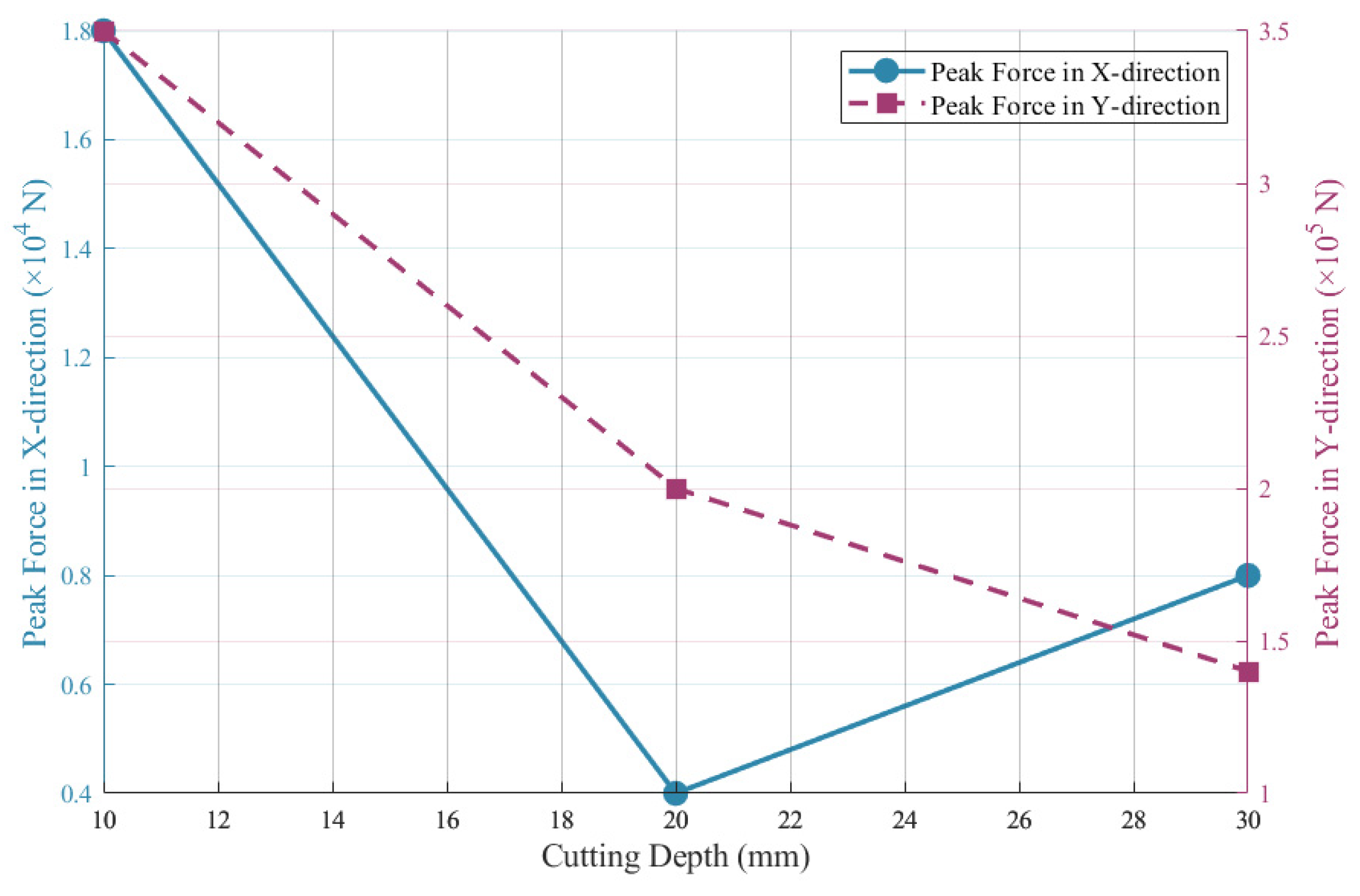

4.2. Cutting Pick Interacting with Hard Nodules in a Coal Seam

4.2.1. Simulation Configurations

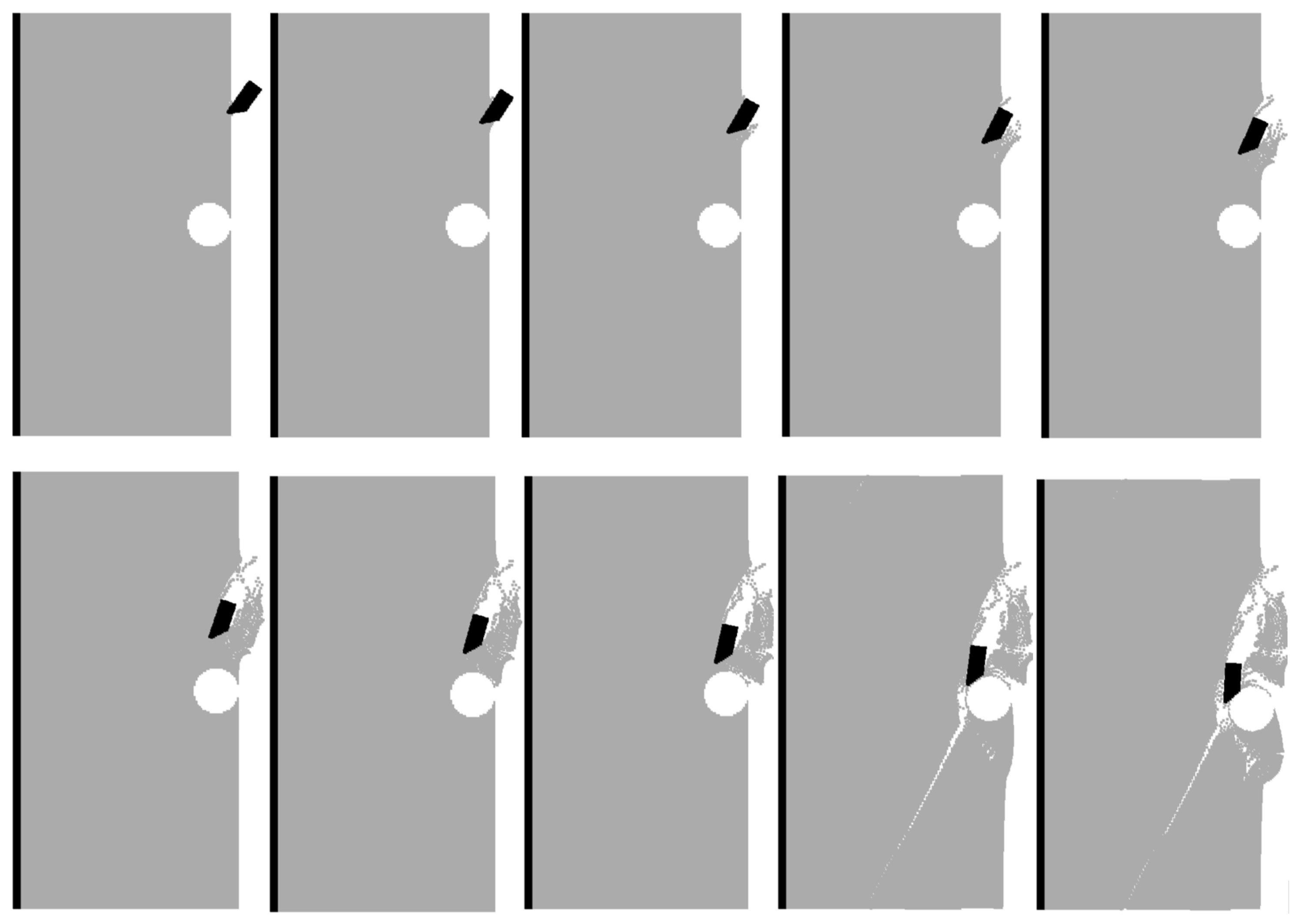

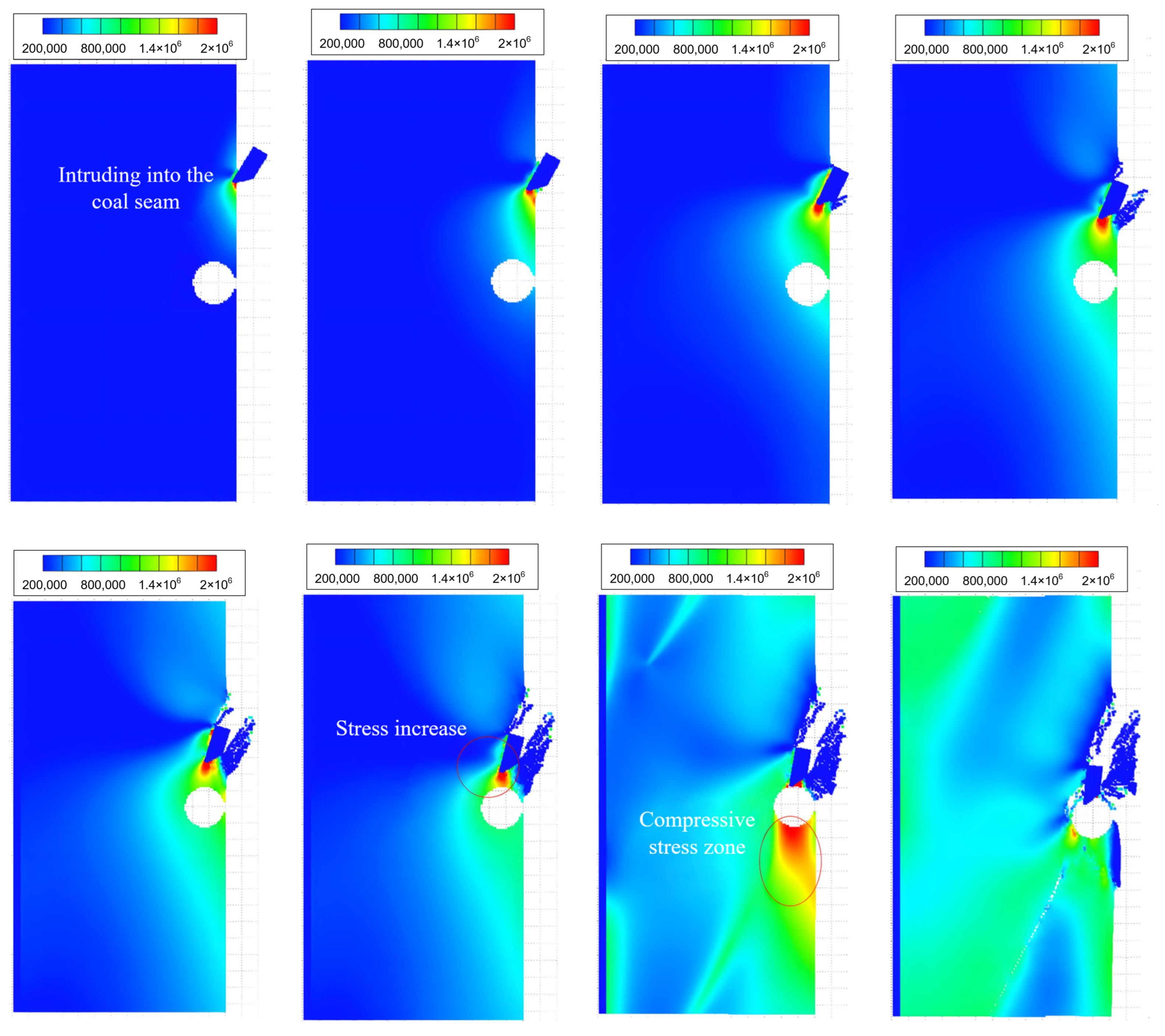

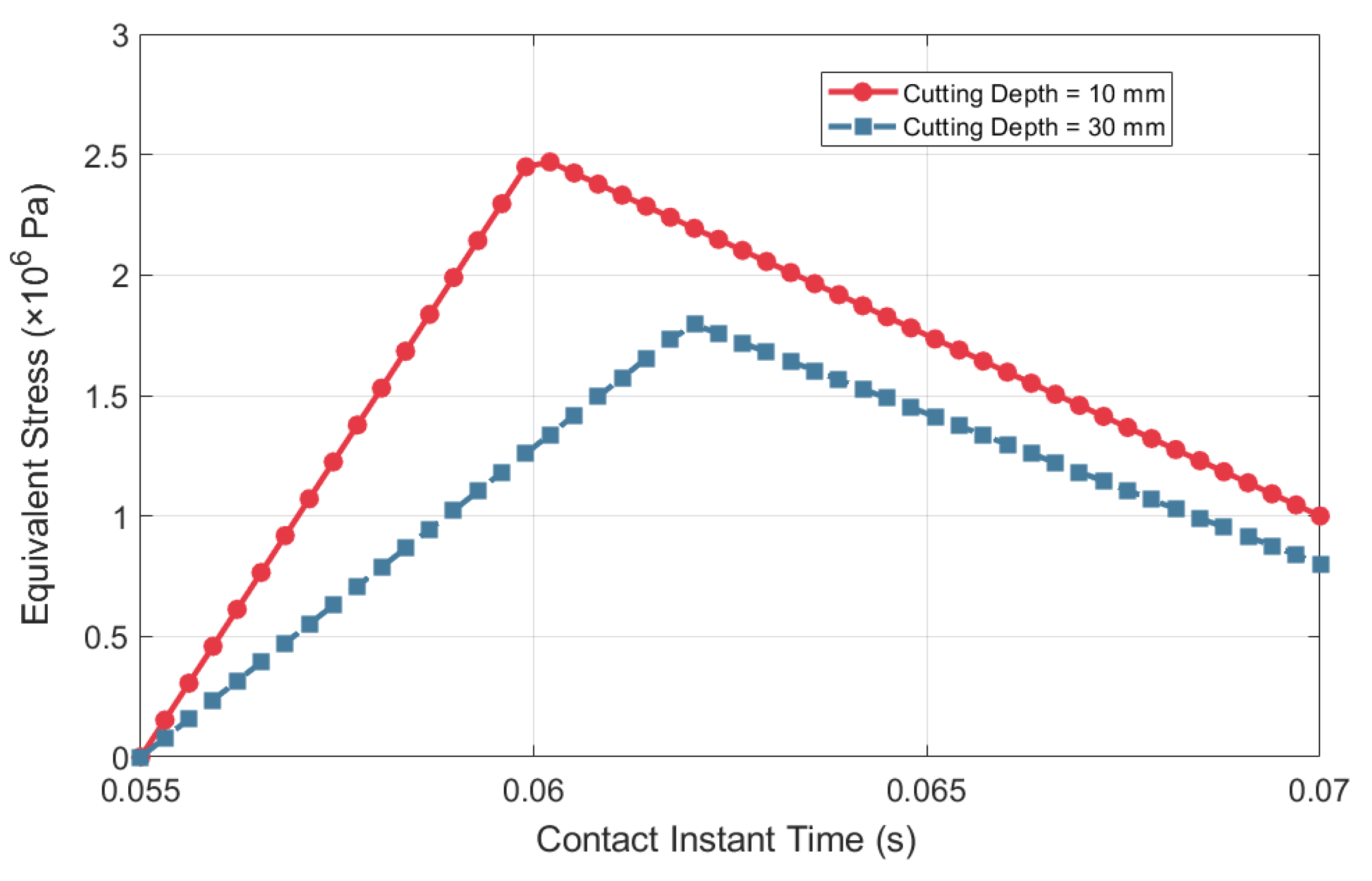

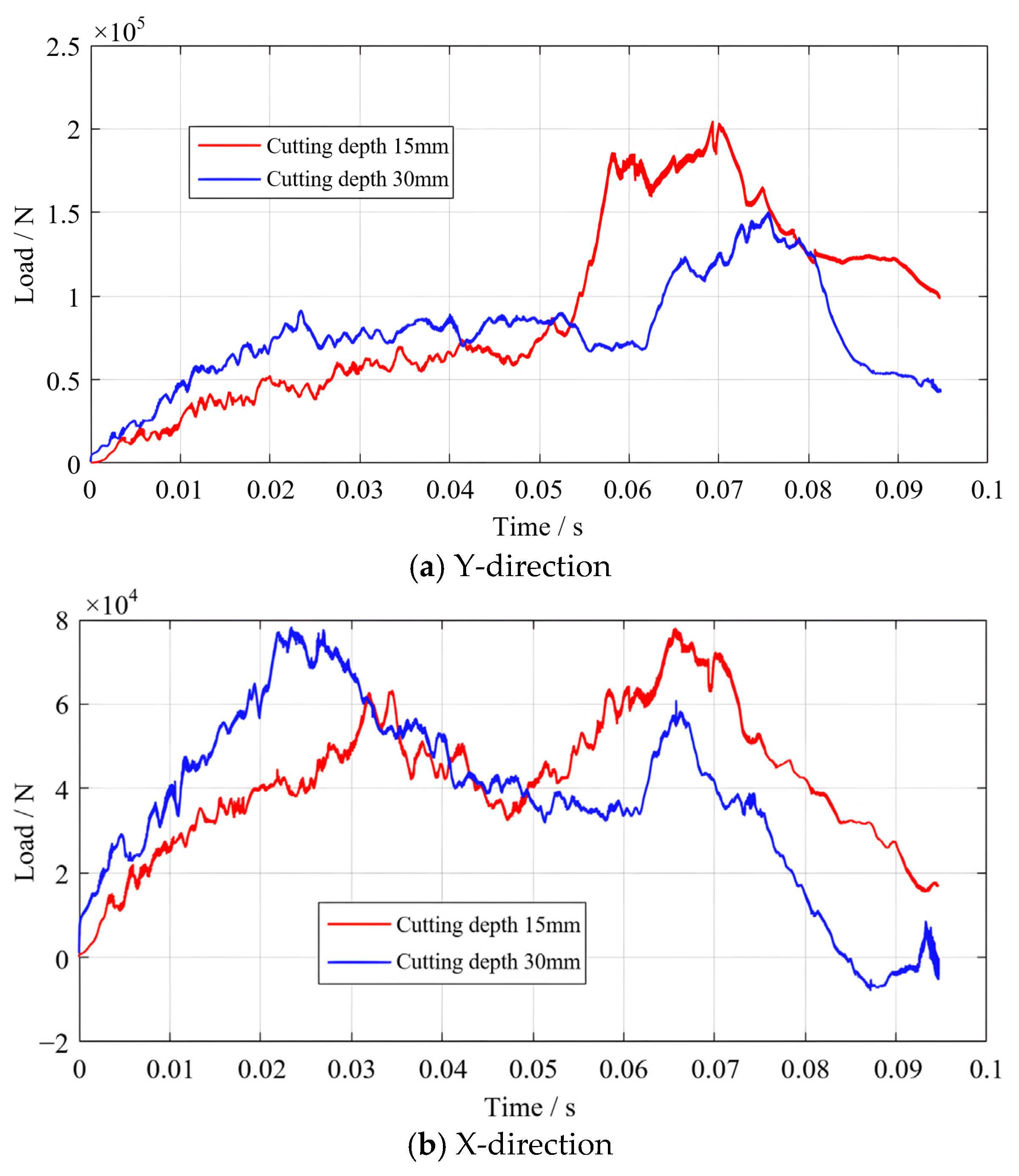

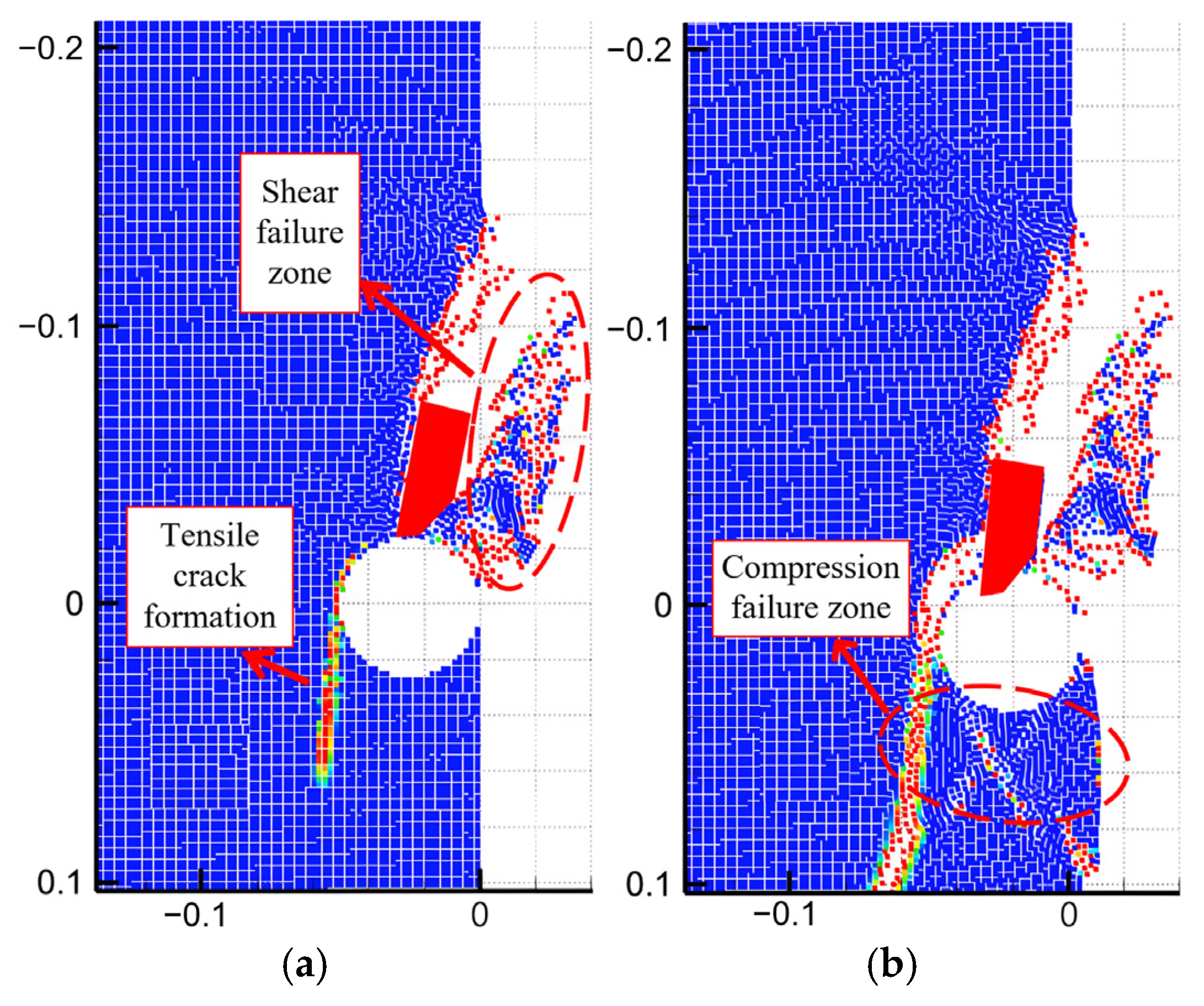

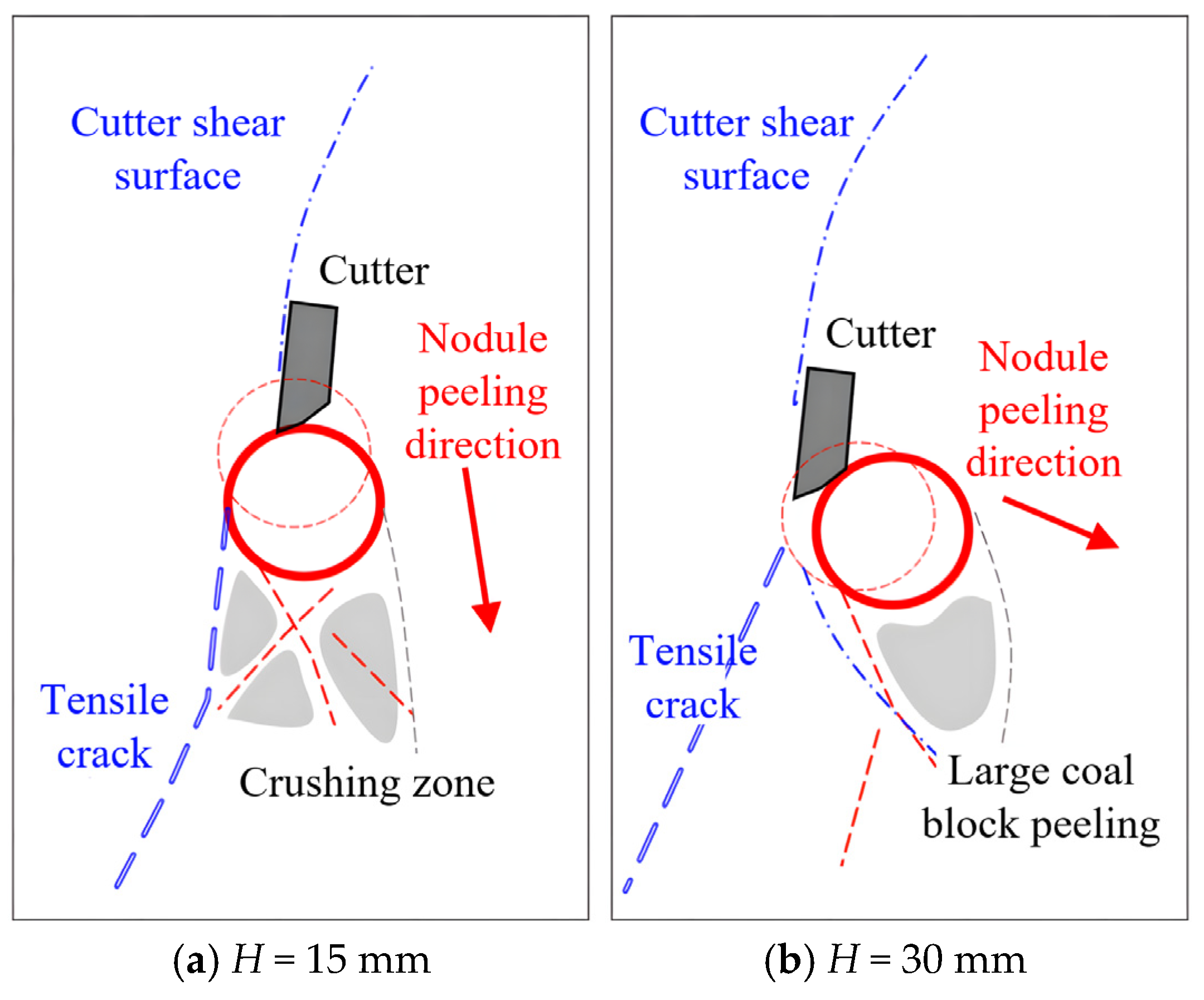

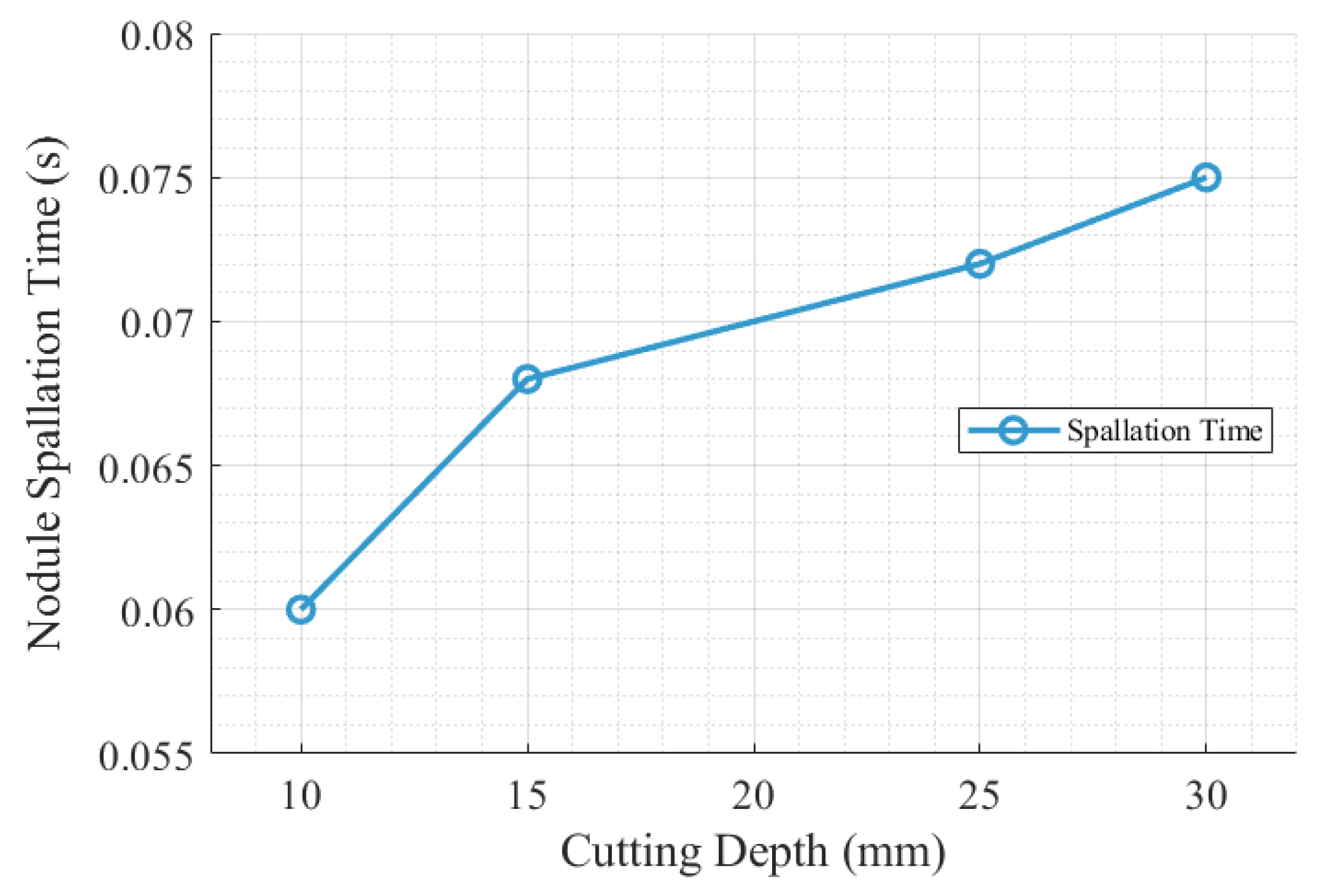

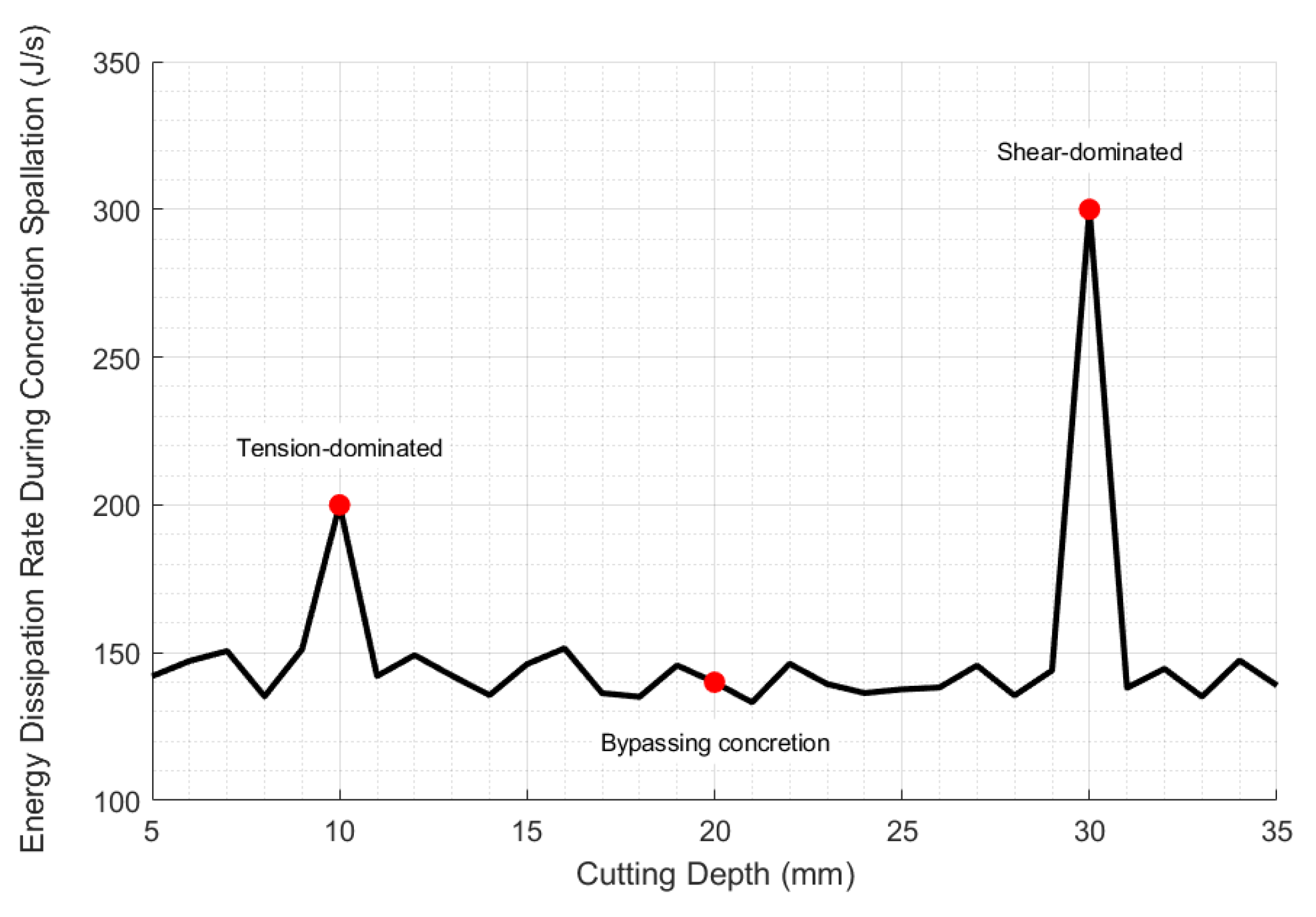

4.2.2. Simulation Results of Cutting into an Intact Coal Wall

4.2.3. Simulation Results of Cutting into a Groove Coal Wall

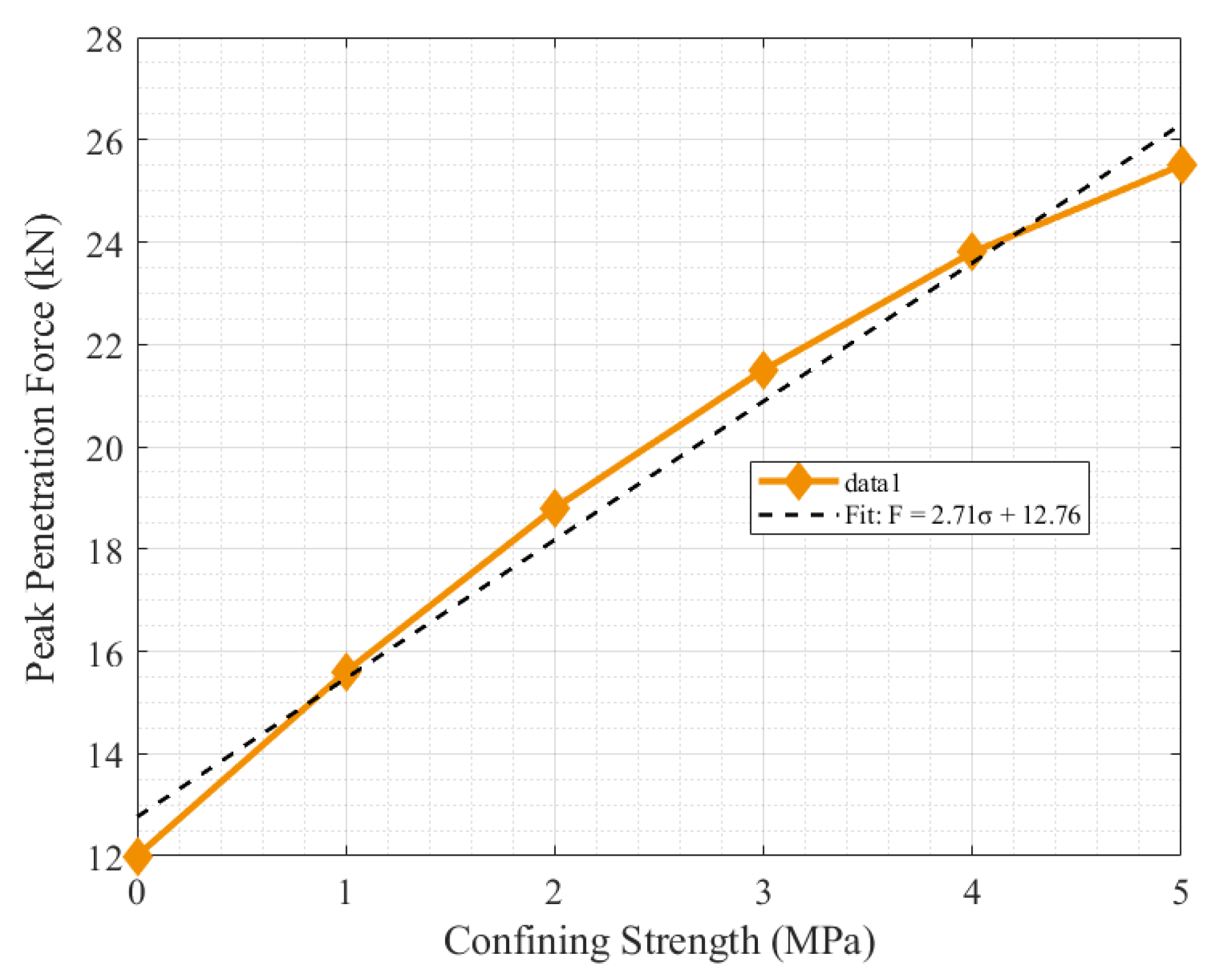

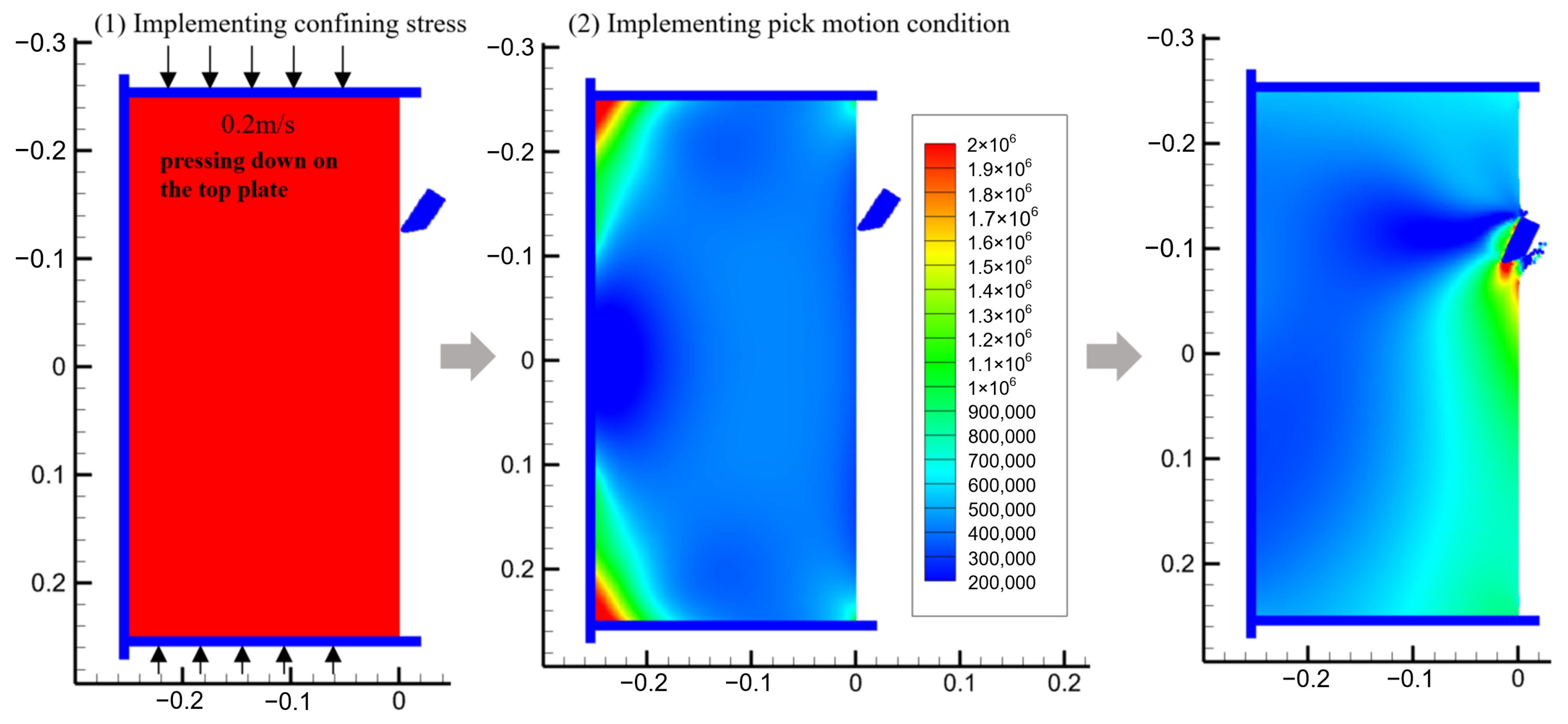

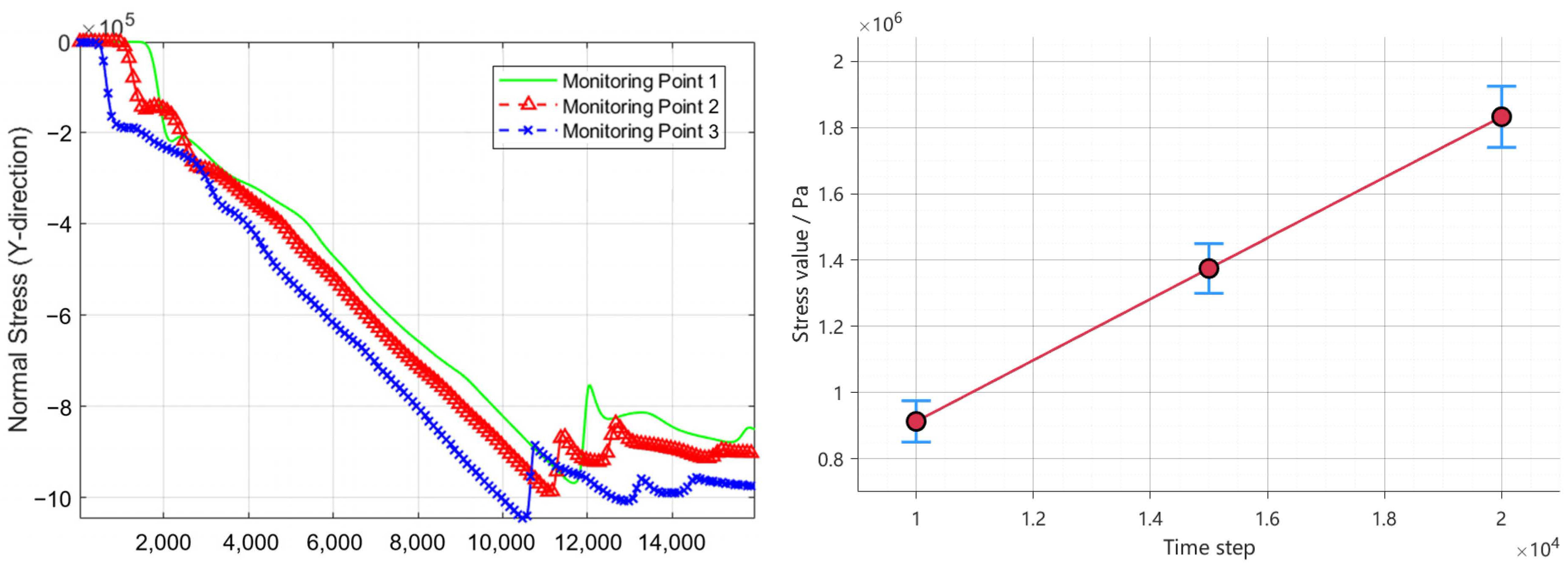

4.2.4. Simulation of Pick Cutting Under Confined Stress Conditions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, D.; Peng, S.; Guo, Y.; Lin, P. Development status and prospect of geological guarantee technology for intelligent coal mining in China. Green Smart Min. Eng. 2024, 1, 433–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, H. Numerical study of forces acting on the drum cutting coal with gangue. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0296624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, Y.; Zheng, Y. Comparative study of the rock-breaking mechanism of a disc cutter and wedge tooth cutter by discrete element modelling. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 2023, 36, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.E.; Kim, M.S.; Yoo, W.K.; Kim, C.-Y. Experimental investigation on the effects of cutting direction and joint spacing on the cuttability behaviour of a conical pick in jointed rock mass. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, D.; Wang, D.; Feng, C. A review of selected solutions on the evaluation of coal-rock cutting performances of shearer picks under complex geological conditions. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 12371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M. Study conical pick cutting performance and fatigue life in breaking rock plate process with numerical simulation. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, P.; Li, D.; Ru, W.; Gong, H.; Wang, M. Hard rock fragmentation by dynamic conical pick indentation under confining pressure. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2024, 183, 105932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Qiao, J.; Zhou, J.; Sun, Z.; Cao, J. Cutting mechanical study of pick cutting coal seams with coal and rock interface. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhao, L.; Shi, B. Coal falling trajectory and strength analysis of drum of shearer based on a bidirectional coupling method. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 9438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, S.F.; Zhou, X.P.; Bi, J.; Xiao, N. The effects of joints on rock fragmentation by TBM cutters using general particle dynamics. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2016, 57, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Yin, F.; Deng, H.; Li, J.; Liu, W. Research on crack propagation and rock fragmentation efficiency under spherical tooth dynamic indentation. Arab. J. Geosci. 2020, 13, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Wu, Y.; Wu, W.; Zhang, H.; Peng, X.; Zhang, X.; Wu, X. Efficient investigation of rock crack propagation and fracture behaviors during impact fragmentation in rockfalls using parallel DDA. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2021, 2021, 5901561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.G.; Wang, J.; Lv, S.; Zhang, X. Numerical simulation analysis of coal rock crushed by disc cutter based on ABAQUS. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 1043, 042010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Shi, X.; Wu, Y. DEM-based 2D numerical simulation of the rock cutting process using a conical pick under confining stress. Comput. Geotech. 2024, 165, 105885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Gao, Q.; Jia, Y.; Zhou, H.; Gao, X.; Jiang, W.; Ma, X. Application of simulation methods and image processing techniques in rock blasting and fragmentation optimization. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 3365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Feng, Y.T.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Z. Discrete element modelling of dynamic behaviour of rockfills for resisting high speed projectile penetration. Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 2021, 127, 721–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, H.; Fukagawa, R.; Sako, K.; Ohno, S. Lagrangian meshfree particles method (SPH) for large deformation and failure flows of geomaterial using elastic–plastic soil constitutive model. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. 2008, 32, 1537–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Liu, X. Improved mesh-free SPH approach for loose top coal caving modeling. Particuology 2024, 95, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhai, M.; Ling, X.; Chu, X.; Hu, B.; Cheng, Y. On the location of multiple failure slip surfaces in slope stability problems using the meshless SPH algorithm. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2020, 2020, 6821548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, T. Research on the coupled water–soil SPH algorithm improvement and application based on two-phase mixture theory. Int. J. Comput. Methods 2022, 19, 2150072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, R.; Fourtakas, G.; Rogers, B.D.; Lombardi, D. A general smoothed particle hydrodynamics (SPH) formulation for coupled liquid flow and solid deformation in porous media. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2024, 419, 116581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.X.; Sun, L.; Chen, Z.; Cheng, C.; Liu, C.F. Multiphase smoothed particle hydrodynamics modeling of forced liquid sloshing. Int. J. Numer. Methods Fluids 2021, 93, 411–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.B.; Zhang, Z.L.; Feng, D.L. A density-adaptive SPH method with kernel gradient correction for modeling explosive welding. Comput. Mech. 2017, 60, 513–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.N.; Le Touzé, D.; Oger, G.; Zhang, A.-M. An accurate SPH Volume Adaptive Scheme for modeling strongly-compressible multiphase flows. Part 1: Numerical scheme and validations with basic 1D and 2D benchmarks. J. Comput. Phys. 2021, 426, 109937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.H.T.; Bui, H.H.; Nguyen, G.D. Effects of material properties on the mobility of granular flow. Granul. Matter 2020, 22, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douillet-Grellier, T.; Jones, B.D.; Pramanik, R.; Pan, K.; Albaiz, A.; Williams, J.R. Mixed-mode fracture modeling with smoothed particle hydrodynamics. Comput. Geotech. 2016, 79, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melosh, H.J.; Ryan, E.V.; Asphaug, E. Dynamic fragmentation in impacts: Hydrocode simulation of laboratory impacts. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 1992, 97, 14735–14759. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G.R.; Liu, M.B. Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics: A Meshfree Particle Method; World Scientific: Singapore, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, X.; Feng, L.; Zhang, Q. Droplet asymmetry bouncing on structured surfaces: A simulation based on SPH method. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2024, 132, 103734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Fu, C.; Zhou, F.; Feng, L.; Zhang, Q. A volume-adaptive smoothed particle hydrodynamics (SPH) model for underwater contact explosion. Theor. Comput. Fluid Dyn. 2025, 39, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Guo, X.; Zhang, Q.; Shen, Z.; Dong, X.; Li, C.; Cao, K. A Lagrangian Mesh-Free Multi-Phase Model for Simulating Complex Dynamics of Bubbly Flows. MetaResource 2025, 2, 11–32. [Google Scholar]

- Das, R.; Cleary, P.W. Effect of rock shapes on brittle fracture using smoothed particle hydrodynamics. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 2010, 53, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Yuan, J.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, S.; Wang, S.; Ma, D.; Huang, Y. Numerical investigation on the influence of cutting parameters on rock breakage using a conical pick. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2024, 312, 110607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter Category | Parameter Name | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drum Parameters | Rotational Speed | 60 | r/min |

| Diameter | 0.5 | m | |

| Cutting Parameters | Cutting Depth (H) | 10.0, 20.0, 30.0 | mm |

| Nodule Diameter | 50.0 | mm | |

| Numerical Simulation Parameters | Number of SPH Particles | 32,051 | - |

| Initial Particle Spacing | 2.0 | mm | |

| Time Step | 2.0 × 10−7 | s | |

| Number of Simulation Steps | 500,000 | - | |

| Total Physical Time | 0.1 | s |

| Cutting Depth/mm | X-Direction N | X-Direction Peak Force Variation Rate (Relative to Cutting Depth 10 mm) | Y-Direction | Y-Direction Peak Force Variation Rate (Relative to Cutting Depth 10 mm) | Mechanical Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 1.8 | 0% | 3.5 | 0% | The pick directly contacts the hard nodule, triggering combined shear–tensile failure, resulting in maximum forces in both X and Y directions |

| 20 | 0.38 | −79% | 2.1 | −40% | The pick trajectory bypasses the nodule, and coal failure is dominated by tensile crack propagation, significantly reducing cutting resistance |

| 30 | 0.77 | −57% | 1.4 | −60% | Without direct nodule contact, the pick must drive a larger volume of coal to undergo shear slip, causing the X-direction force to rebound while the Y-direction force continues to decrease. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tian, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Q.; Song, Y.; Han, Y.; Feng, L.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, X. Numerical Investigation on Rotational Cutting of Coal Seam by Single Cutting Pick. Processes 2026, 14, 531. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14030531

Tian Y, Zhang S, Zhang Q, Song Y, Han Y, Feng L, Liu H, Zhang Y, Dong X. Numerical Investigation on Rotational Cutting of Coal Seam by Single Cutting Pick. Processes. 2026; 14(3):531. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14030531

Chicago/Turabian StyleTian, Ying, Shengda Zhang, Qiang Zhang, Yan Song, Yongliang Han, Long Feng, Huaitao Liu, Yingchun Zhang, and Xiangwei Dong. 2026. "Numerical Investigation on Rotational Cutting of Coal Seam by Single Cutting Pick" Processes 14, no. 3: 531. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14030531

APA StyleTian, Y., Zhang, S., Zhang, Q., Song, Y., Han, Y., Feng, L., Liu, H., Zhang, Y., & Dong, X. (2026). Numerical Investigation on Rotational Cutting of Coal Seam by Single Cutting Pick. Processes, 14(3), 531. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14030531