Modeling of Methane + Propane Mixed-Gas Hydrate Formation Processes in a Batch-Type Reactor Under Isothermal Condition

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. CH4 + C3H8 Mixed-Gas Hydrate Formation Experiments

2.1. Experimental Procedures

2.2. Experimental Results

3. Numerical Calculation Models for the Formation Processes of Methane + Propane Mixed-Gas Hydrates

3.1. Thermodynamic Model

3.1.1. Phase Equilibrium

3.1.2. Vapor Phase

3.1.3. Liquid Phase

3.1.4. Hydrate Phase

3.2. Calculation Method

3.2.1. Matching to Experimental Conditions

3.2.2. Numerical Models

- Homogeneous-type model: after the hydrate forms, guest molecules are redistributed to result in a hydrate phase of uniform composition.

- Layered-type model: after some hydrate forms, that hydrate composition is fixed, resulting in hydrate layers of different composition.

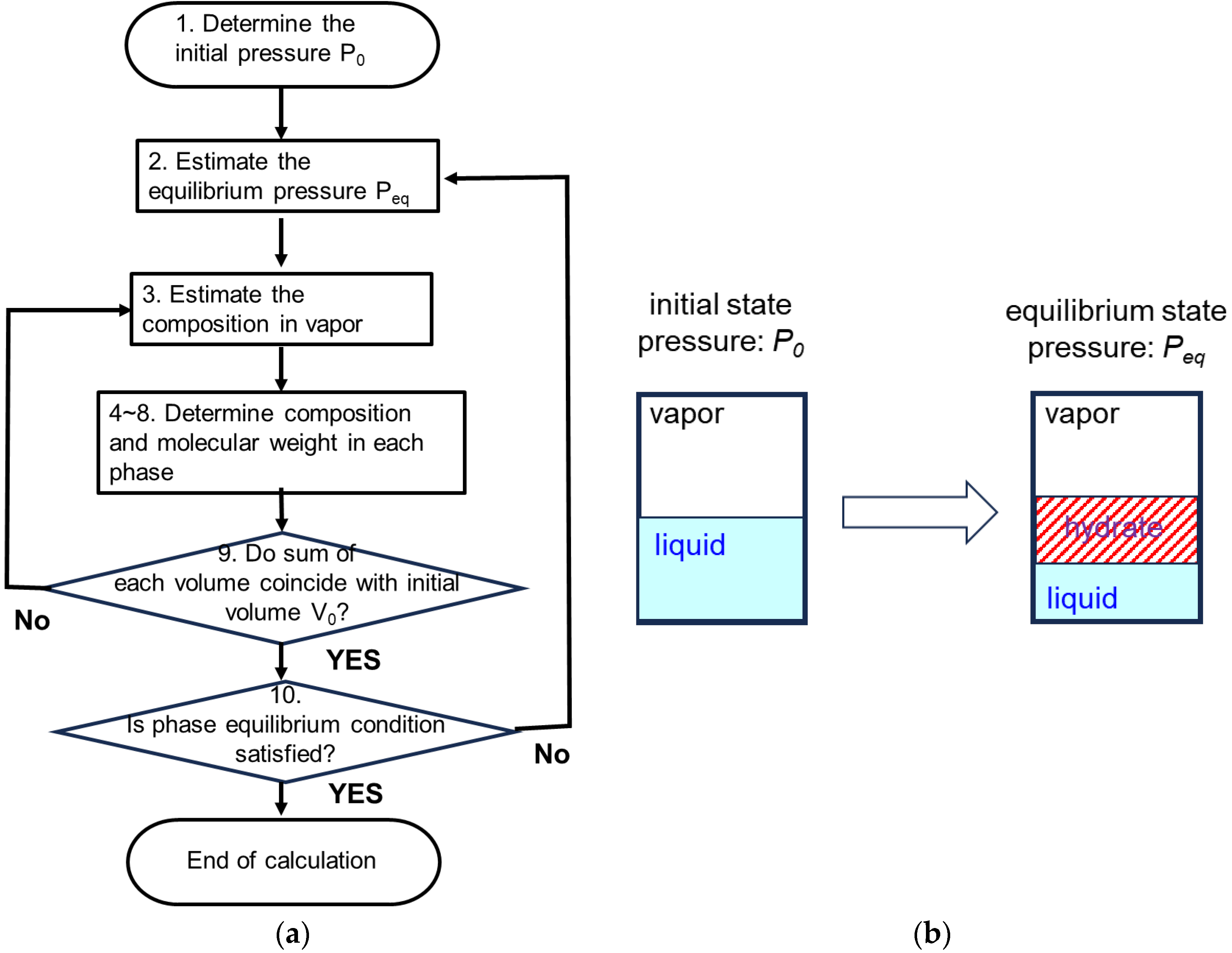

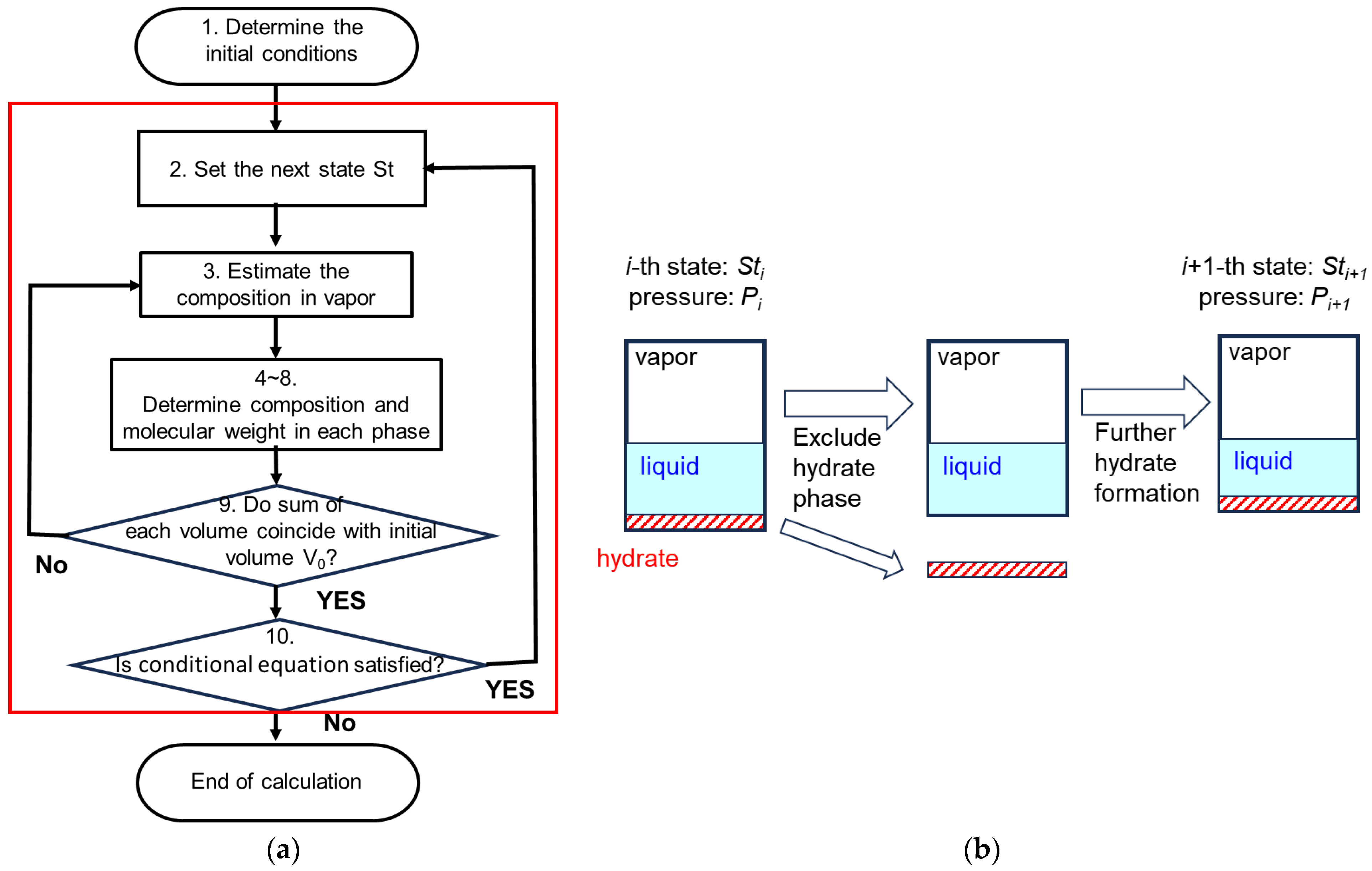

3.2.3. Calculation Flow for the Homogeneous-Type Model

- Determine the initial state

- Vapor phase: Determine the initial pressure P0 and determine the molecular weights of CH4 and C3H8 based on Equations (3)–(8).

- Liquid phase: Determine the molecular weight of water based on the density of water.

- Consider an arbitrary state St in which three phases exist: vapor, liquid, and hydrate. Assume that the pressure P of the vapor phase in this state is in the range 0 < P < P0.

- Assume that the composition ratios in the vapor phase in the arbitrary state St are based on each vapor phase molecular weight by

- Here, the water ratio is Pwsat,L/P, based on Equation (13) and the P from step 2.

- The vapor phase fugacity fV is calculated using Equations (3)–(9).

- Using Henry’s law (11–12), the composition ratios of the liquid phase based on each liquid-phase molecular weight is calculated using the fugacity of vapor phase fV.

- Calculate cage occupancies in the hydrate phase using Equations (20)–(23) and the fugacity of vapor phase fV.

- Based on the cage occupancies, calculate the hydrate composition based on each hydrate-phase molecular weight by .

- Using the composition of each phase from 3, 5, and 7, convert Equations (24)–(26) into a system of linear equations with three unknowns and solve them to find the molecular weight of each phase for each substance.

- Calculate the volume of each phase using Equations (3), (14) and (18) and determine whether Equation (27) is sufficiently satisfied.

- Satisfied: go to 10.

- Not satisfied: the assumed vapor composition in 3 cannot exist, so try again with a different composition.

- Calculate the fugacity using Equations (10), (15), and (16) to determine whether the phase equilibrium condition (2) is sufficiently satisfied.

- Satisfied: pressure P, assumed in 2, and the arbitrary state St are considered to be in equilibrium. As such, the calculation ends.

- Not satisfied: pressure P assumed in 2 could not be the equilibrium pressure, so try again with a different pressure as the equilibrium pressure.

3.2.4. Calculation Flow for Layered-Type Model

- Determine the initial state.

- Vapor phase: Determine the initial pressure P0 to be calculated, and determine the molecular weights of CH4 and C3H8 based on Equations (3)–(8).

- Liquid phase: Determine the molecular weight of water based on the water density.

- Consider state Sti after some crystallization processes have occurred, dropping pressure to Pi.

- As with the homogeneous-type model, assume the vapor phase in state Sti has a composition based on each vapor phase molecular weight as .

- Here, the water ratio is Pwsat,L/P, based on Equation (13) and P set in 2 above.

- Calculate the vapor phase fugacity fV using Equations (3)–(9).

- Using Henry’s law (Equations (11) and (12)) and the vapor phase fugacity fV, calculate the composition ratio of the liquid phase based on each liquid-phase molecular weight as .

- Calculate cage occupancies in the hydrate phase using Equations (20)–(23) and fV.

- Based on the cage occupancies, calculate the composition ratio of the hydrate phase, based on each hydrate-phase molecular weight as .

- Using the composition ratios of each phase found in 4, 5, and 7, convert Equations (24)–(26) into a system of linear equations with three unknowns and solve them to find the molecular weight of each phase for each substance.

- Calculate the volume of each phase using Equations (3), (14), and (18) and determine whether the following equation is sufficiently satisfied:

- Satisfied: go to 10.

- Not satisfied: the composition ratio of vapor phase assumed in 3 cannot exist, so try again with a different composition ratio.

- Calculate the fugacity using Equations (10), (15), and (16) to determine whether the conditional Equation (28) is satisfied.

- Satisfied: go to 11.

- Not satisfied: the pressure Pi set in 2 and the state at that time Sti have reached equilibrium, so we assume that hydrate formation has stopped and thus end the calculation.

- As the pressure Pi set in 2 was not the equilibrium pressure, we assume the gas hydrate crystallization will continue. Given that the composition in the gas hydrate phase does not change (in this model), the gas hydrate that has formed will be excluded. Then, repeating from 2, the process will proceed as we consider the state Sti+1 where the pressure has decreased to Pi+1.

- From then on, steps 3 to 11 are repeated until gas hydrate formation stops.

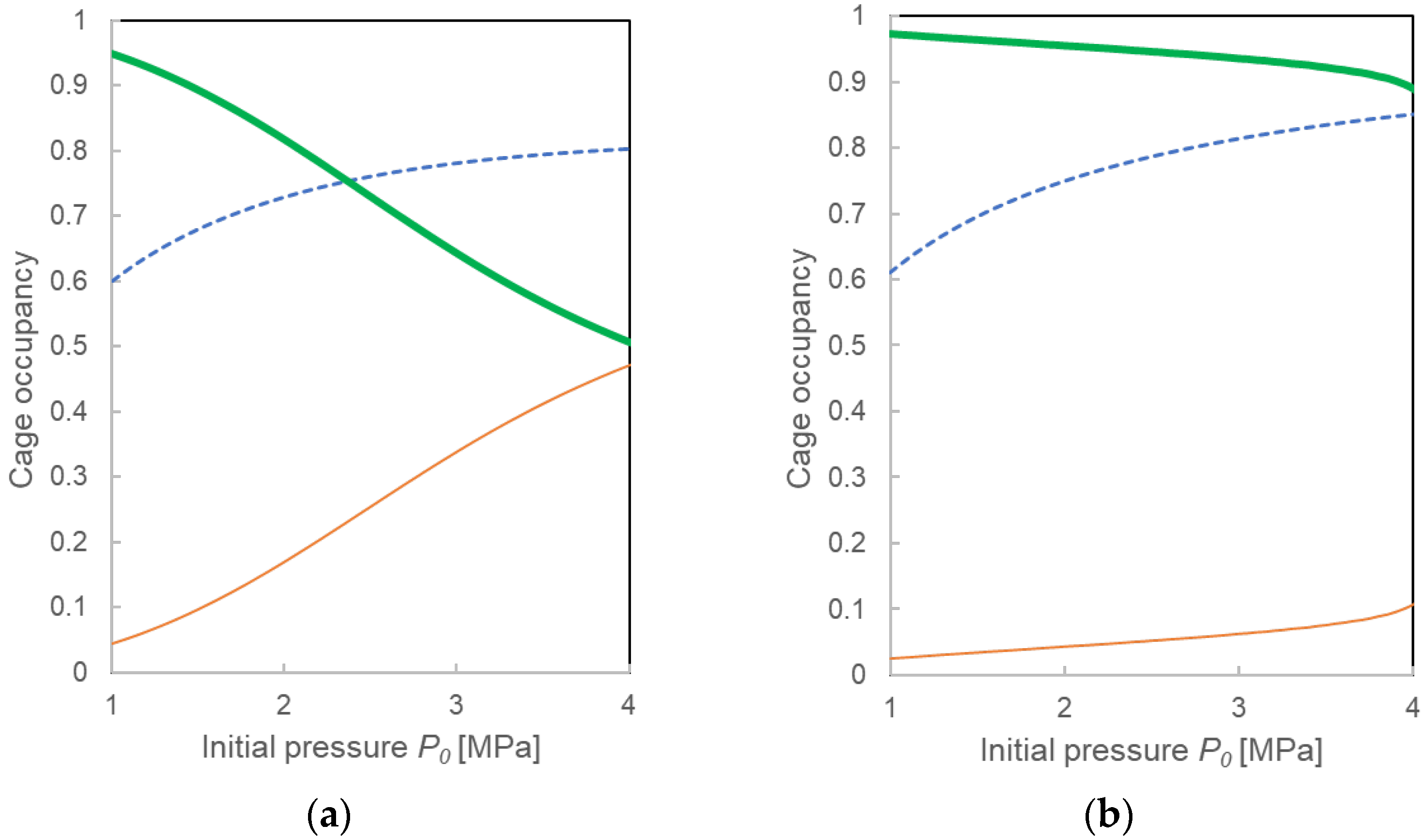

3.3. Calculation Results

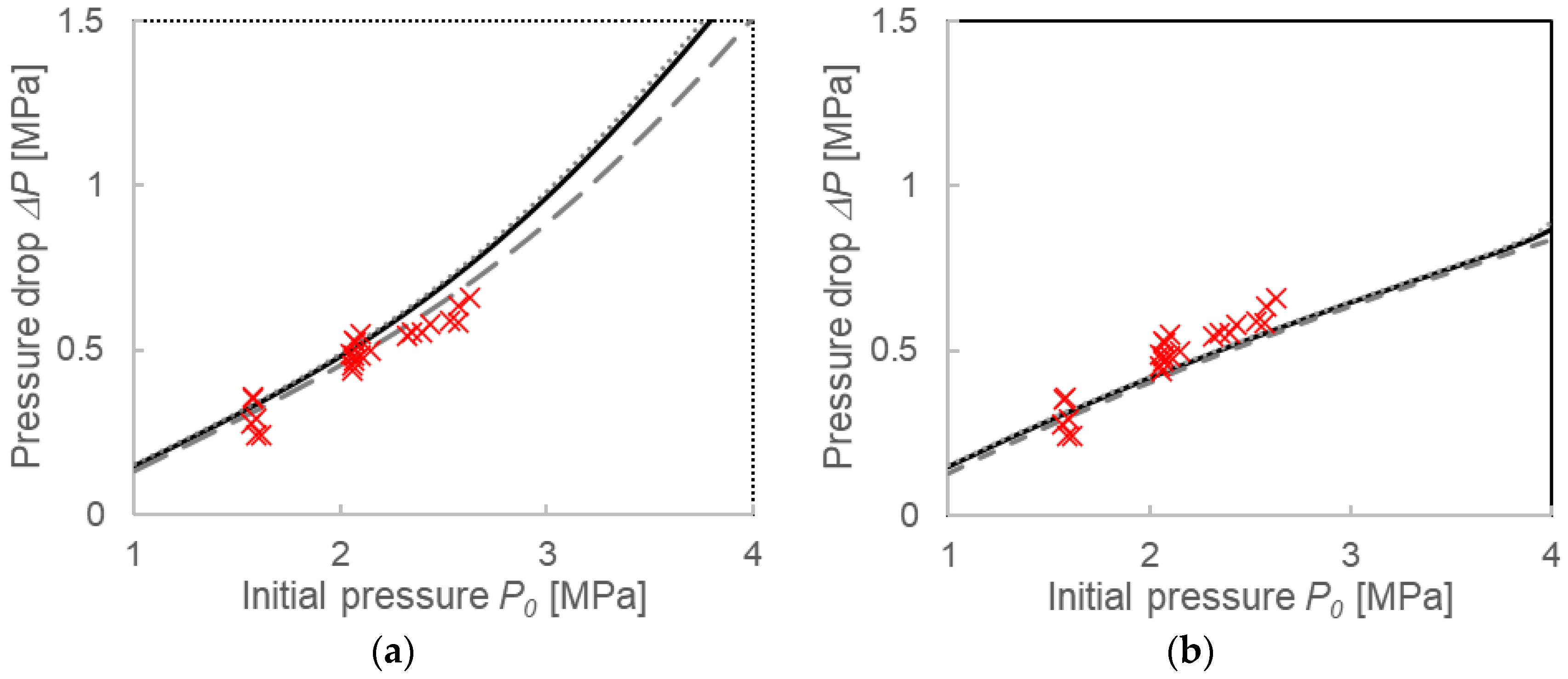

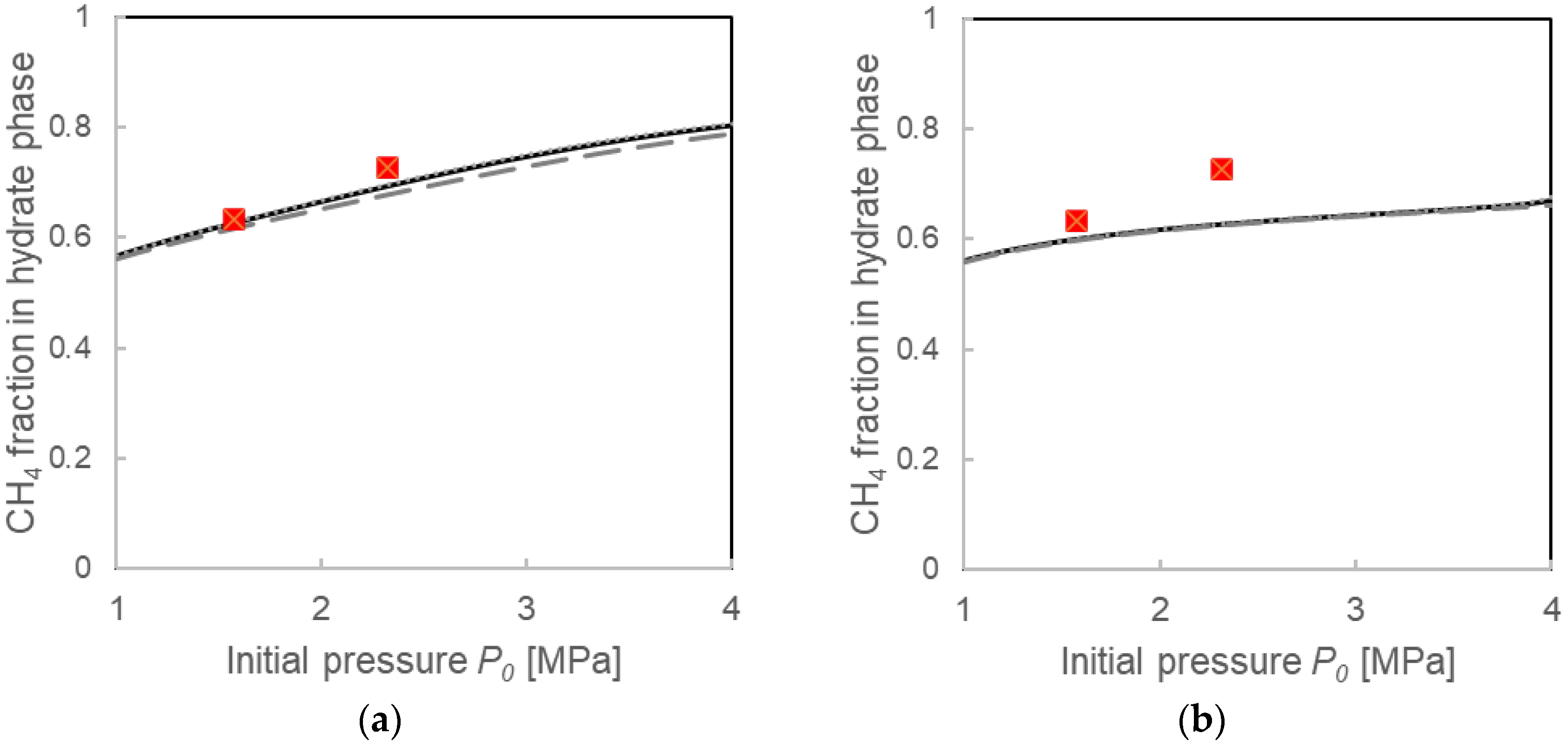

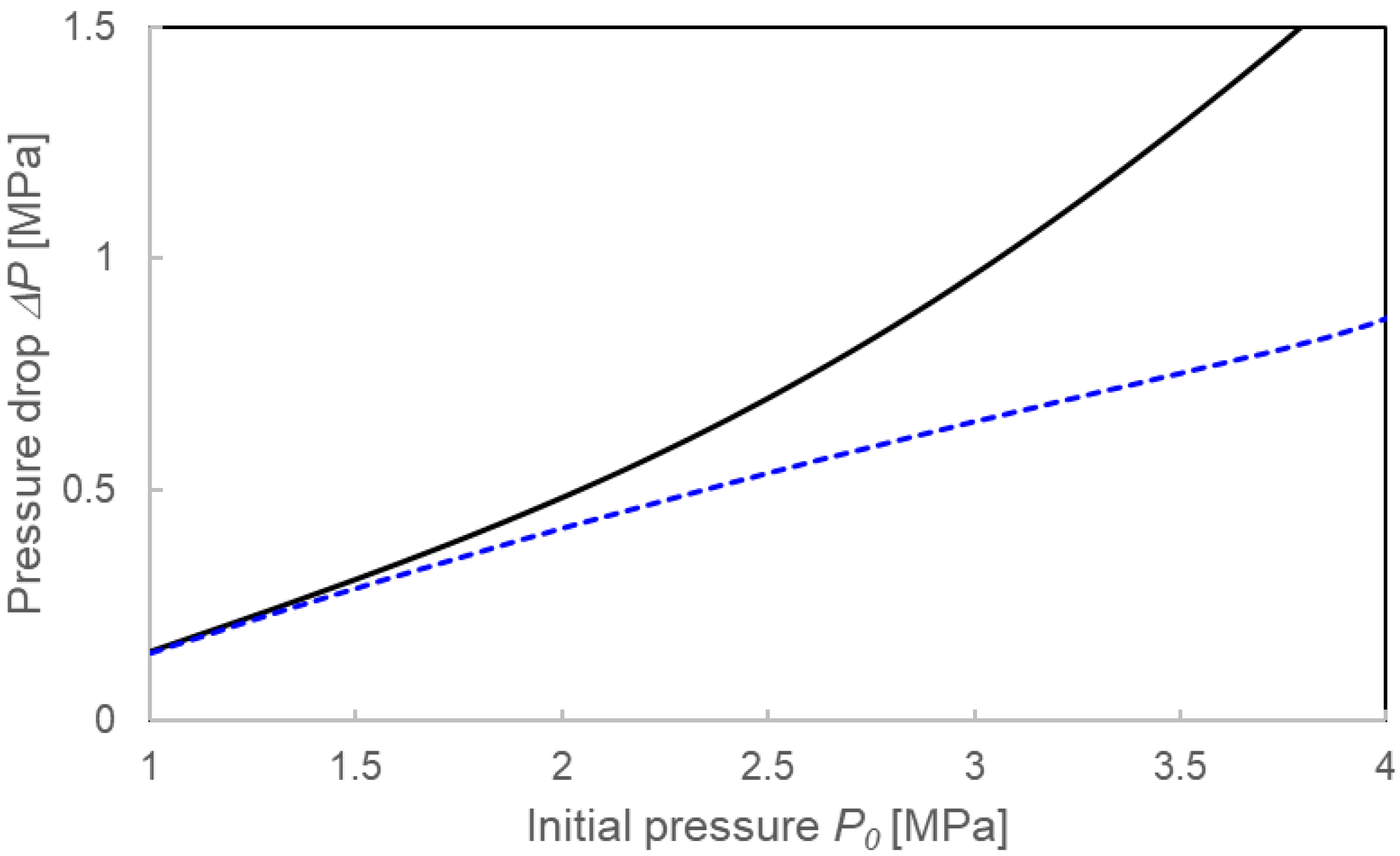

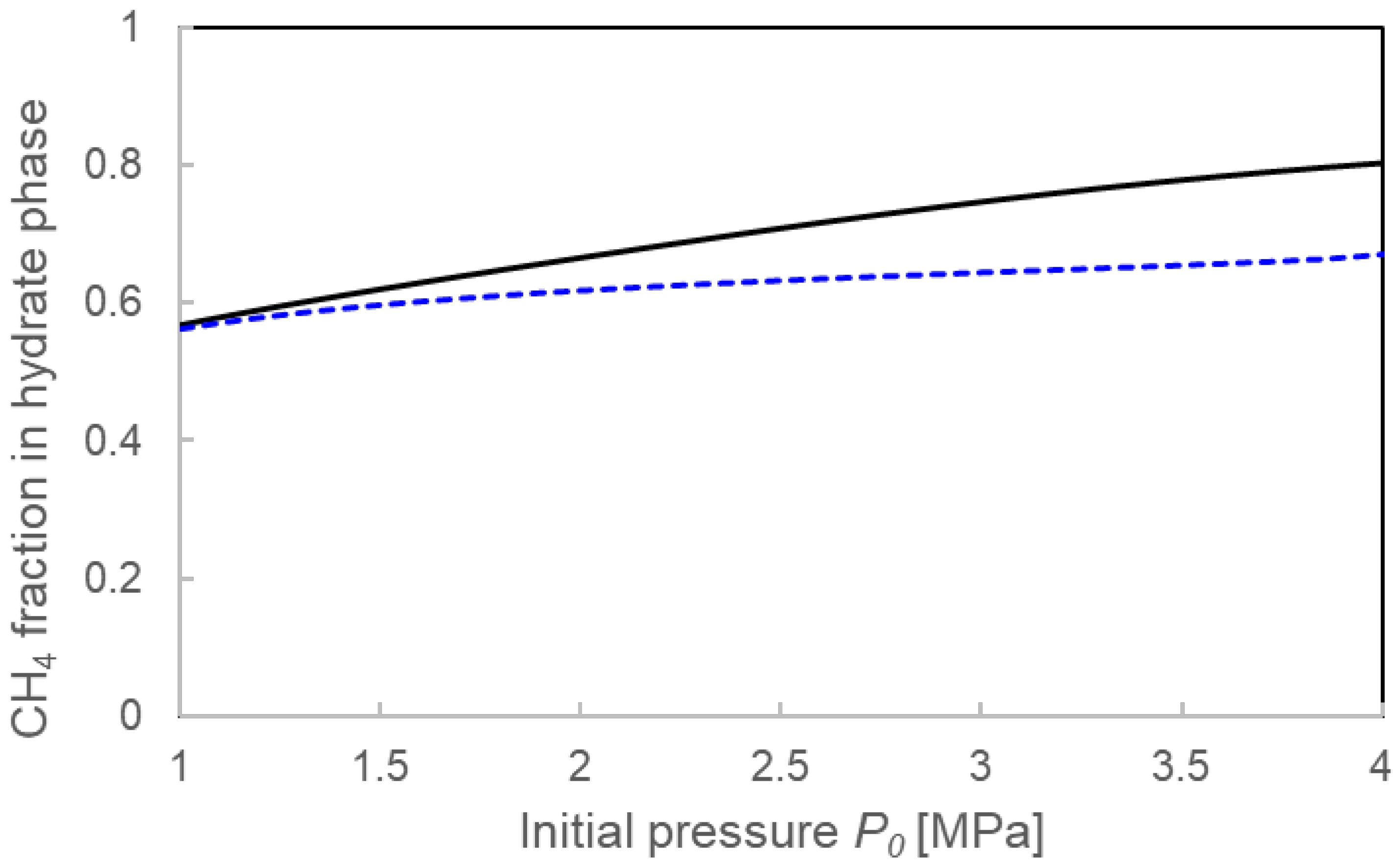

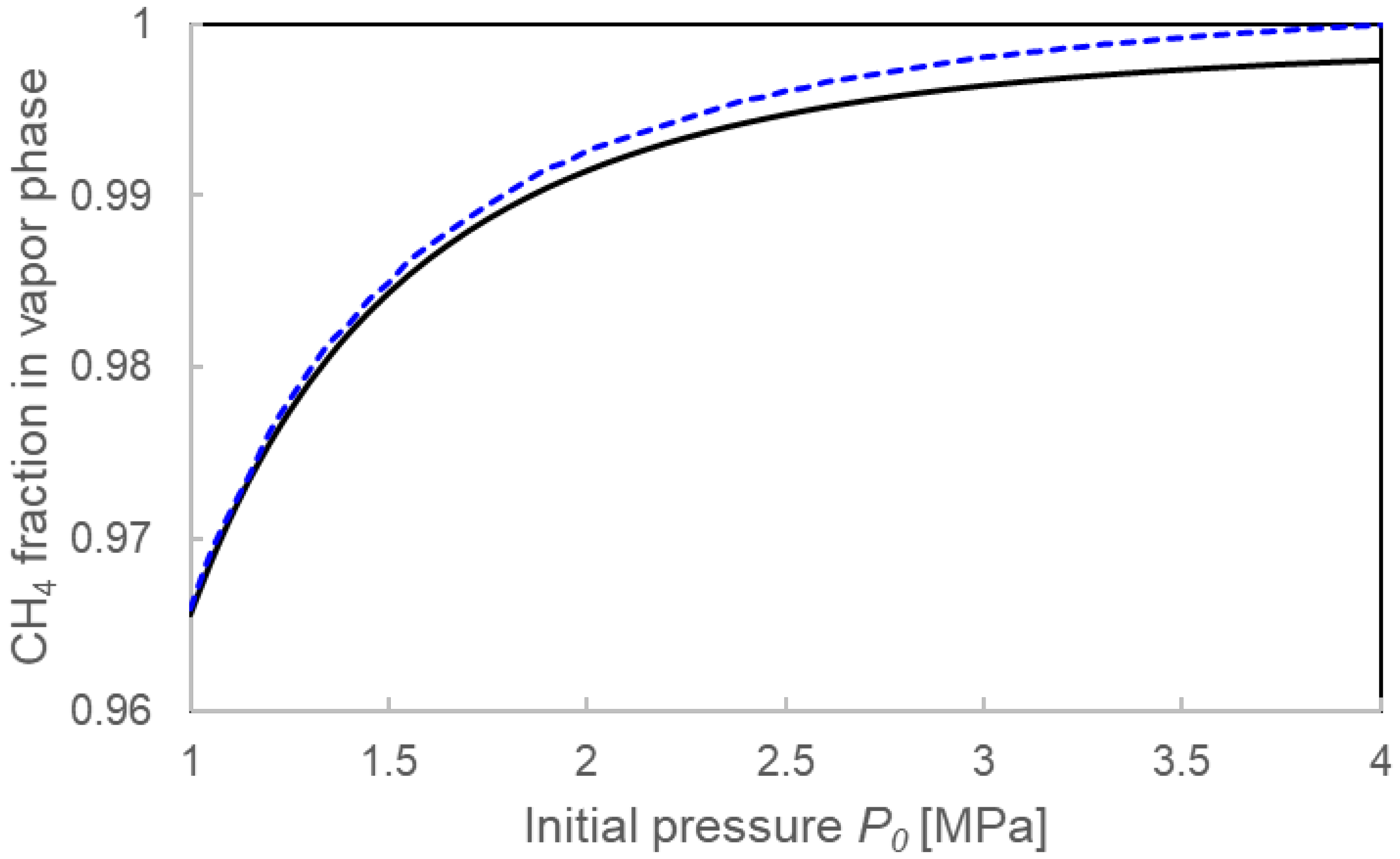

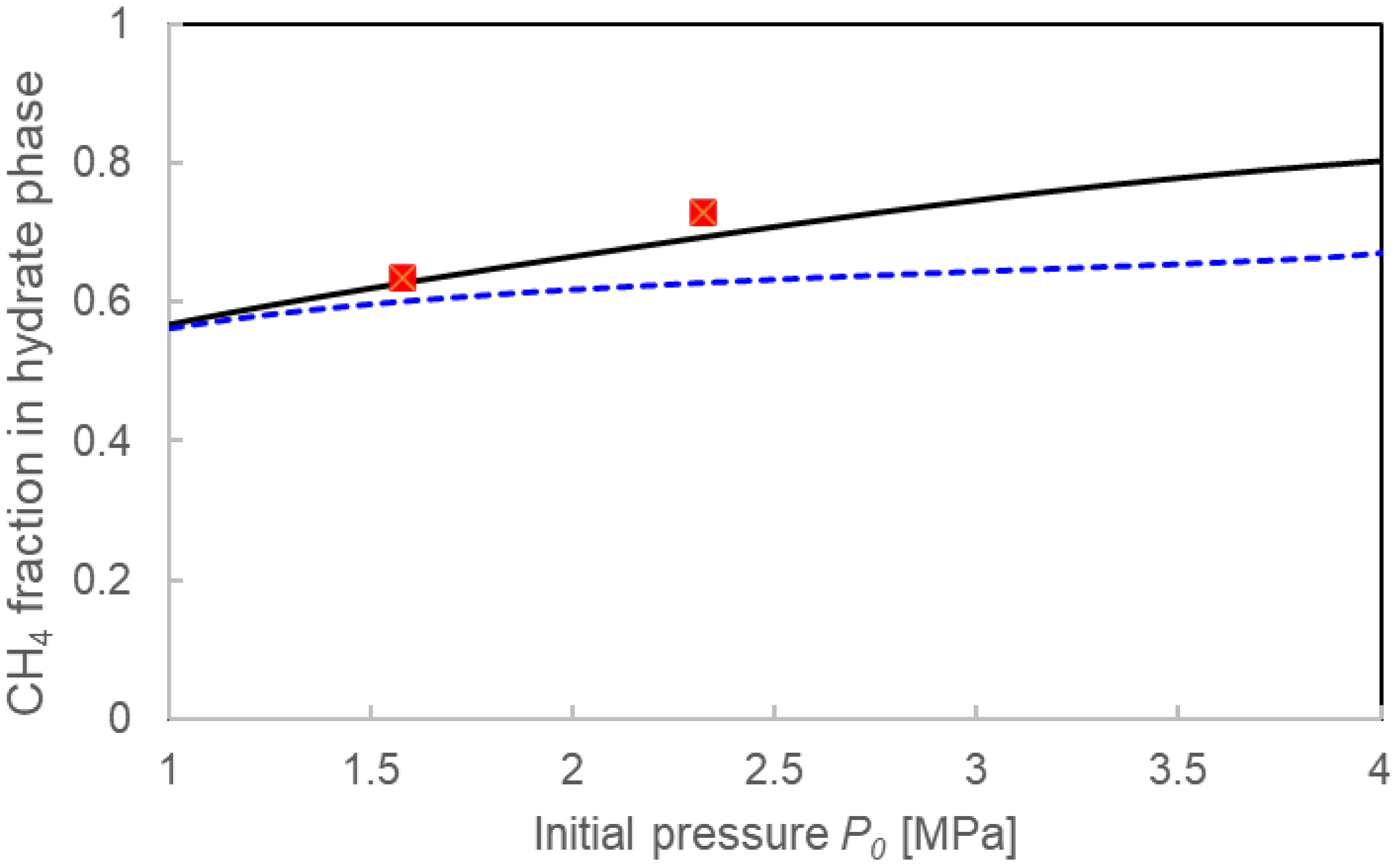

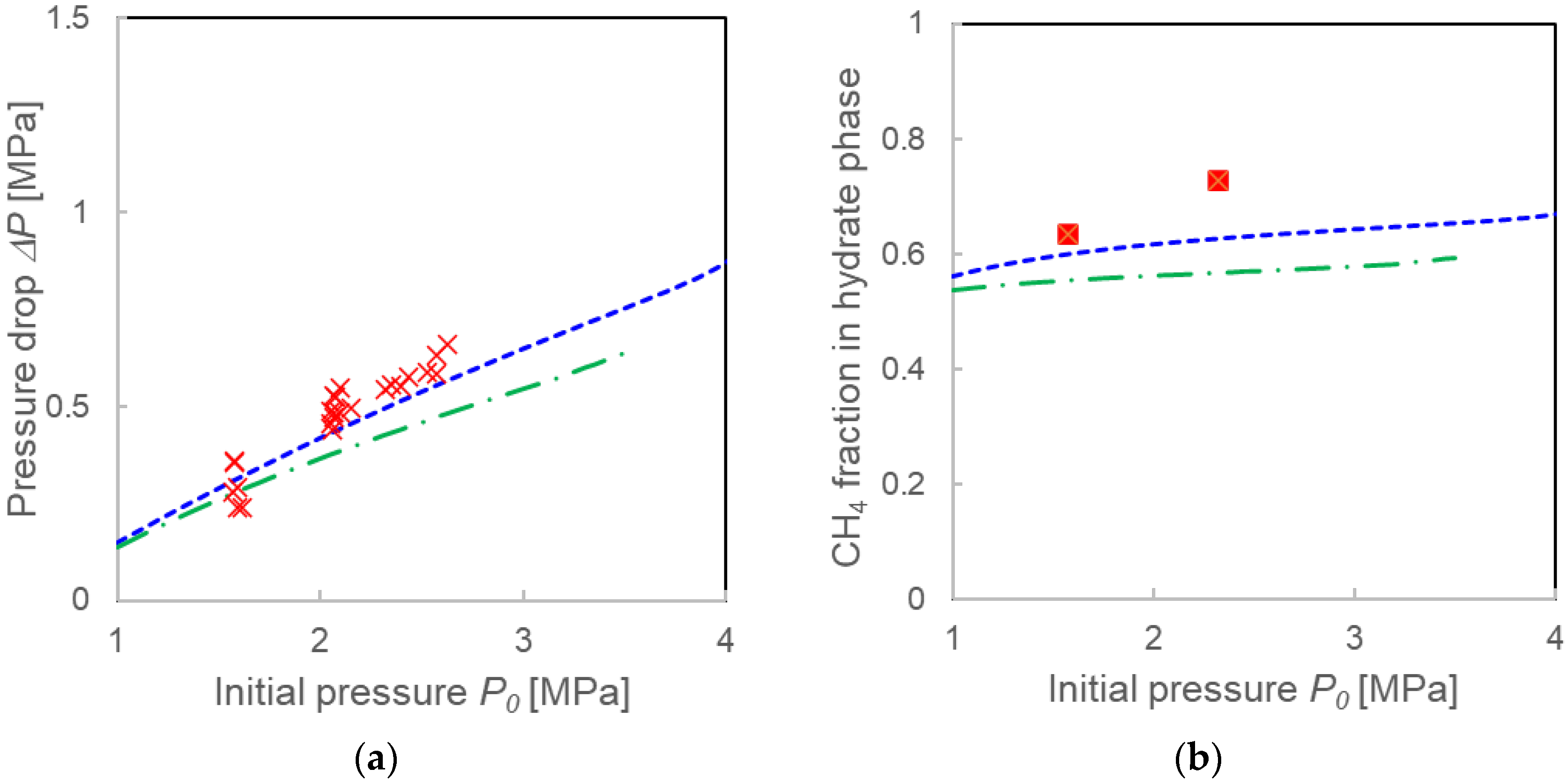

3.3.1. Pressure Drop ΔP and Compositions for the Two Calculation Models

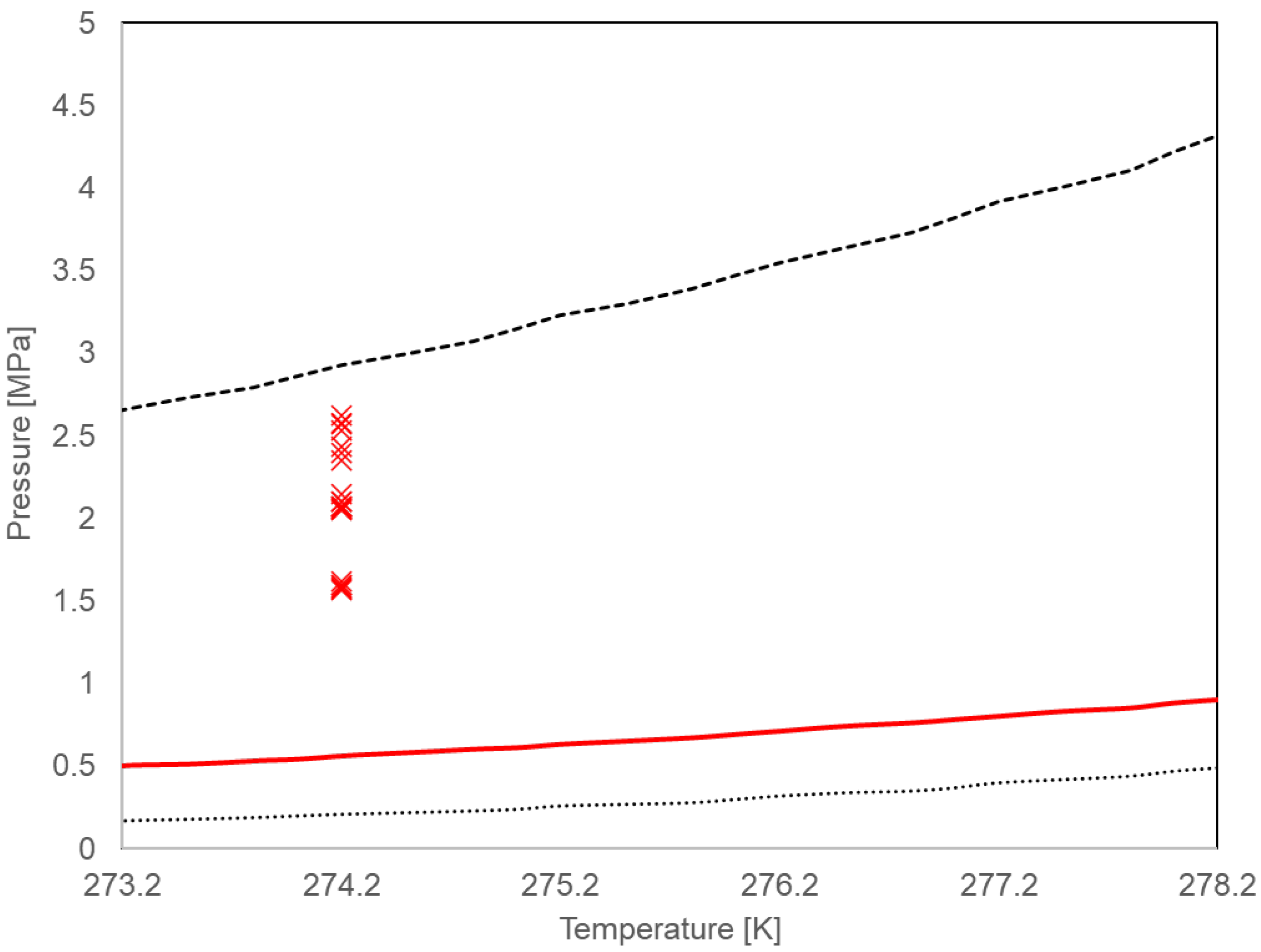

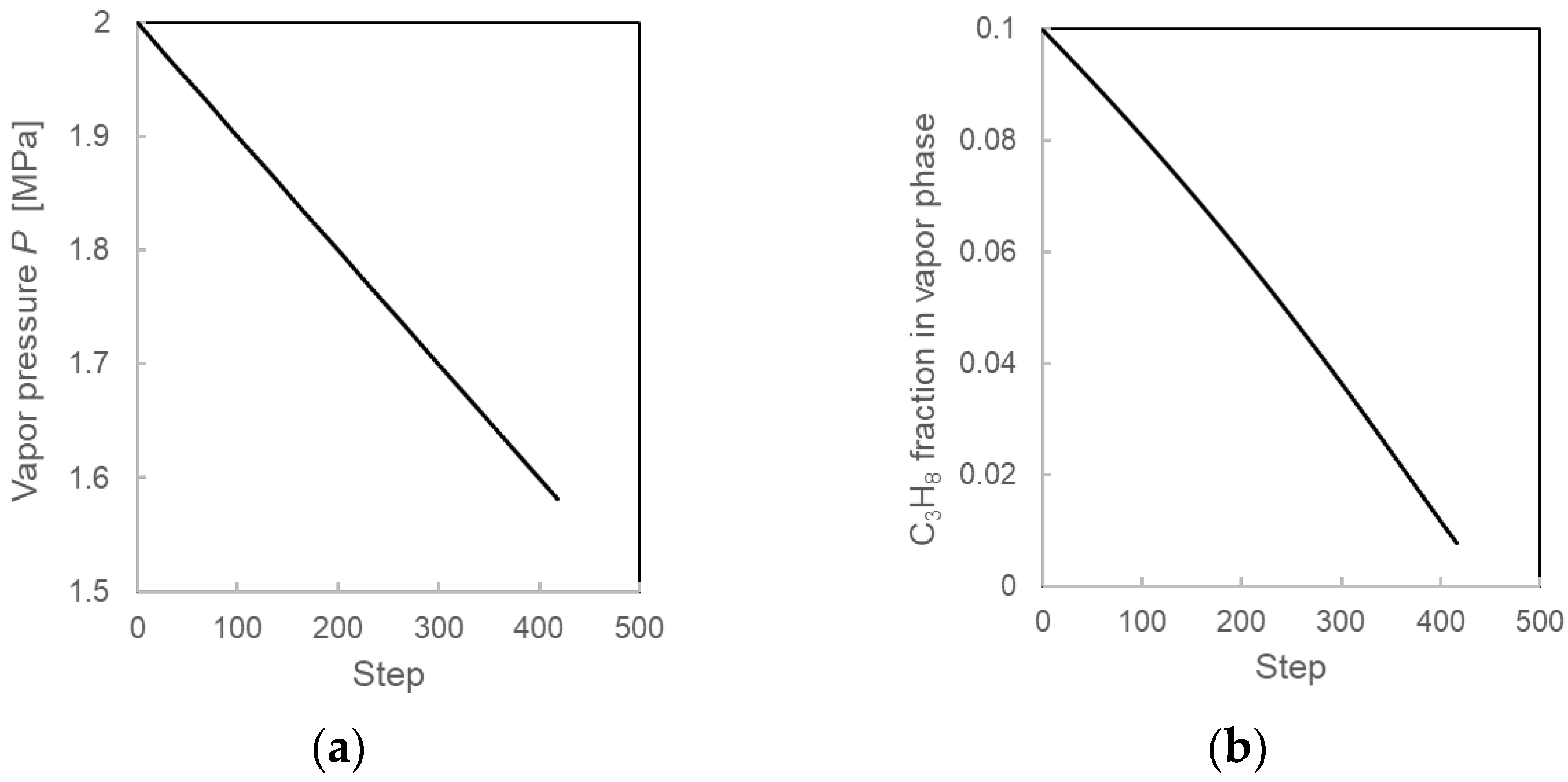

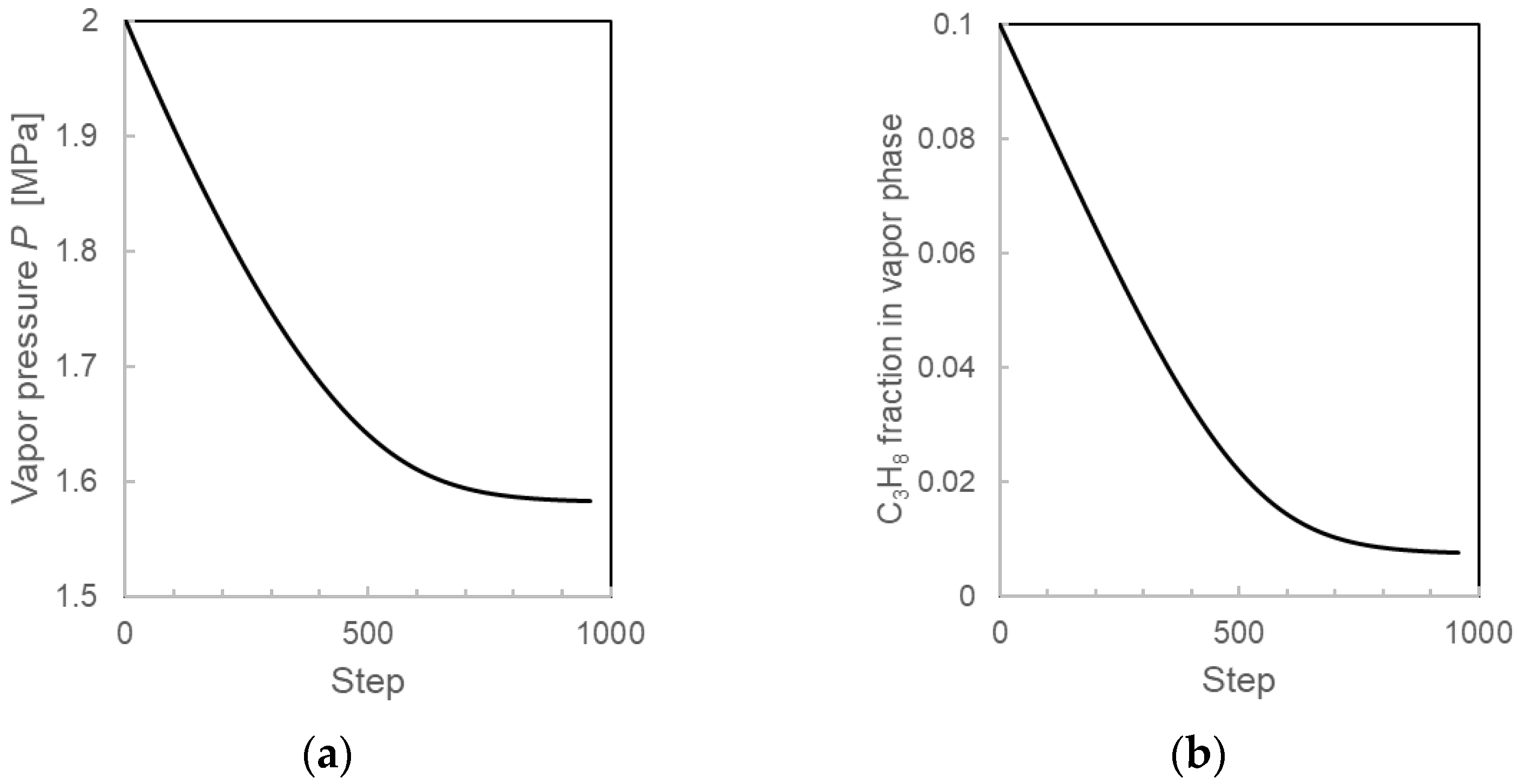

3.3.2. Calculation Results During the Formation Process from the Layered-Type Model

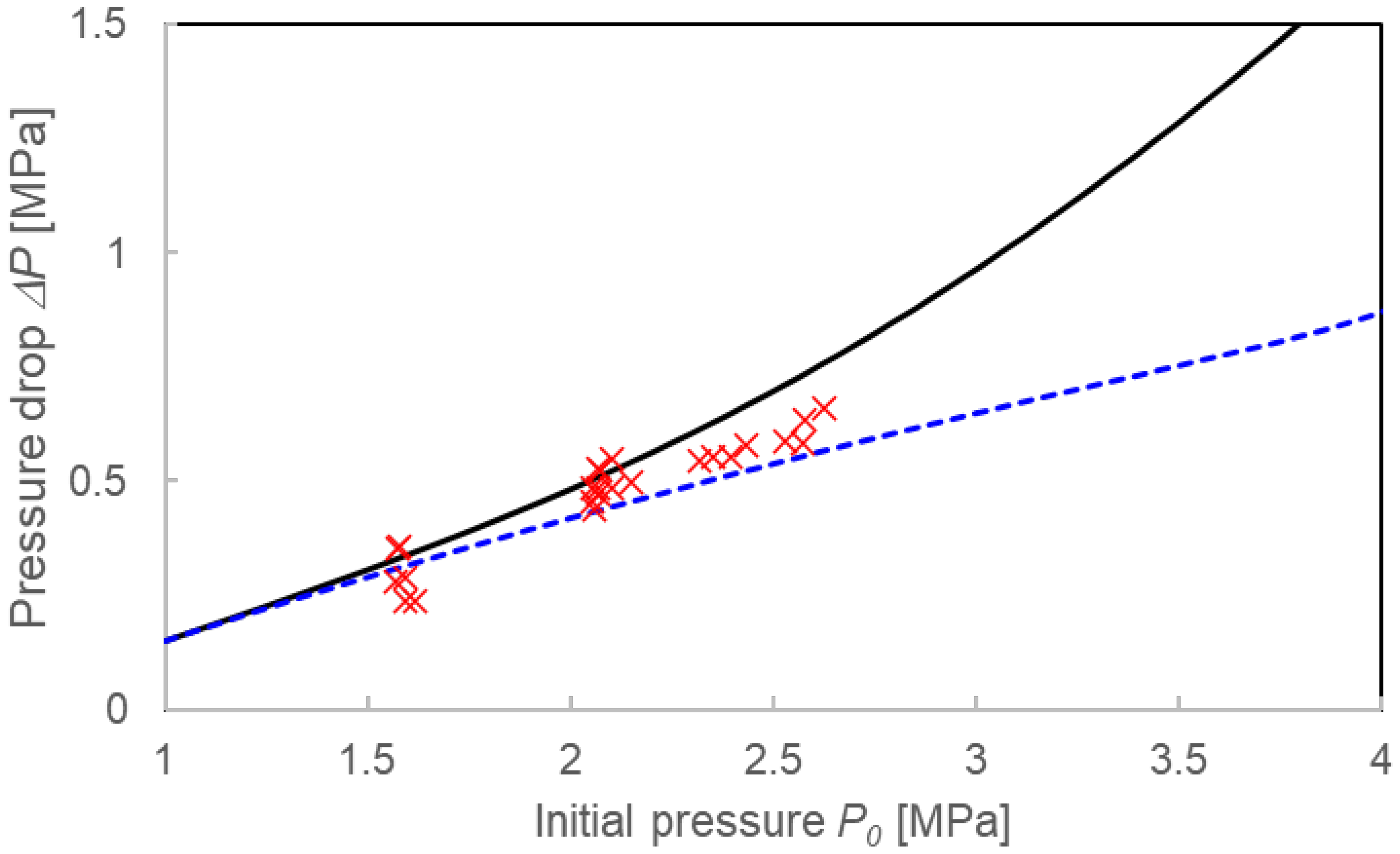

4. Comparison of Model Calculation Results with Experimental Data

4.1. Validation of Two Calculation Models

4.2. Comparison with Calculations Using the Instantaneous Equilibrium Assumption

4.3. Formation Mechanisms of Mixed-Gas Hydrates Considered from a Comparison of Two Models

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CSMHYD | Name of software that can calculate the equilibrium condition of gas hydrates, a code developed in the Colorado Schools of Mines [12]. |

Appendix A. Experimental Data List

| Initial Pressure P0 [MPa] | Equilibrium Pressure Peq [MPa] | Pressure Drop ΔP [MPa] | CH4 Concentration in Hydrate Phase * |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.568 | 1.290 | 0.278 | |

| 1.576 | 1.222 | 0.354 | 0.634 ± 0.002 |

| 1.580 | 1.222 | 0.358 | |

| 1.593 | 1.354 | 0.239 | |

| 1.595 | 1.305 | 0.290 | |

| 1.618 | 1.379 | 0.239 | |

| 2.052 | 1.565 | 0.487 | |

| 2.056 | 1.602 | 0.454 | |

| 2.058 | 1.619 | 0.439 | |

| 2.066 | 1.537 | 0.529 | |

| 2.068 | 1.584 | 0.484 | |

| 2.070 | 1.600 | 0.470 | |

| 2.075 | 1.552 | 0.523 | |

| 2.102 | 1.619 | 0.483 | |

| 2.102 | 1.555 | 0.547 | |

| 2.149 | 1.652 | 0.497 | |

| 2.320 | 1.776 | 0.544 | 0.727 ± 0.002 |

| 2.350 | 1.796 | 0.554 | |

| 2.396 | 1.844 | 0.552 | |

| 2.433 | 1.866 | 0.577 | |

| 2.530 | 1.943 | 0.587 | |

| 2.573 | 1.989 | 0.584 | |

| 2.576 | 1.943 | 0.633 | |

| 2.626 | 1.965 | 0.661 |

Appendix B. Temperature Sensitivity of the Calculation Results

References

- Gudmundsson, J.S.; Mork, M.; Graff, O.F. Hydrate non-pipeline technology. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Gas Hydrates, Yokohama, Japan, 19–23 May 2002; pp. 19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Takaoki, T. Natural gas transportation in form of hydrate. J. Jpn. Assoc. Pet. Technol. 2008, 73, 158–163, (In Japanese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehder, G.; Eckl, R.; Elfgen, M.; Falenty, A.; Hamann, R.; Kahler, N.; Kuhs, W.F.; Osterkamp, H.; Windmeier, C. Methane hydrate pellet transport using the self-preservation effect: A techno-economic analysis. Energies 2012, 5, 2499–2523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri, Z.; Reza, M.; Nazari, S.K.; Mehdizaheh, A. Natural gas transportation and storage by hydrate technology: Iran case study. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2014, 21, 846–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mimachi, H.; Takahashi, M.; Takeya, S.; Gotoh, Y.; Yoneyama, A.; Hyodo, K.; Takeda, T.; Murayama, T. Effect of Long-Term Storage and Thermal History on the Gas Content of Natural Gas Hydrate Pellets under Ambient Pressure. Energy Fuels 2015, 29, 4827–4834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mimachi, H.; Takeya, S.; Gotoh, Y.; Yoneyama, A.; Hyodo, K.; Takeda, T.; Murayama, T. Dissociation behaviors of methane hydrate formed from NaCl solutions. Fluid Phase Equilib. 2016, 413, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuo, S.; Umeda, H.; Takeya, S.; Fujita, T. A Feasibility Study on Hydrate-Based Technology for Transporting CO2 from Industrial to Agricultural Areas. Energies 2017, 10, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchida, K.; Watanabe, S. Development of Natural Gas Transportation Technology Using Hydrates: World’s First Natural Gas Hydrate Transport Demonstration Project. Enermix 2021, 100, 210–214. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Sloan, E.D.; Koh, C.A. Clathrate Hydrates of Natural Gases, 3rd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2008; p. 752. [Google Scholar]

- Uchida, T.; Moriwaki, M.; Takeya, S.; Ikeda, I.Y.; Ohmura, R.; Nagao, J.; Minagawa, H.; Ebinuma, T.; Narita, H.; Gohara, K.; et al. Two-step formation of methane-propane mixed gas hydrates in a batch-type reactor. AIChE J. 2004, 50, 518–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, T.; Mori, Y.H. Thermodynamic simulations of hydrate formation from gas mixtures in batch operations. Energy Convers. Manag. 2007, 48, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CSMHYD, a program package accompanying the following book: Sloan, E.D., Jr. In Clathrate Hydrates of Natural Gases, 2nd ed.; Revised and Expanded; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1998; p. 705.

- Uchida, T.; Sugibuchi, R.; Hayama, M.; Yamazaki, K. Supersaturation dependent nucleation of methane plus propane mixed-gas hydrate. J. Chem. Phys. 2024, 160, 074502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunneman, K.; Sum, A.K. p2f-hydratecalc: A web Python-based tool for the prediction of natural gas hydrate equilibrium and inhibition. SoftwareX 2025, 32, 102422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Waals, J.H.; Platteeuw, J.C. Clathrate Solutions. Adv. Chem. Phys. 1958, 2, 1–57. [Google Scholar]

- Klauda, J.B.; Sandler, S.I. A Fugacity Model for Gas Hydrate Phase Equilibria. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2000, 39, 3377–3386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, D.Y.; Robinson, D.B. A New Two-Constant Equation of State. Ind. Eng. Chem. Fundamen. 1976, 15, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaubert, J.N.; Mutelet, F. VLE predictions with the Peng-Robinson equation of state and temperature dependent kij calculated through a group contribution method. Fluid Phase Equilib. 2004, 224, 285–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.W.; Privat, R.; Jaubert, J.N. Predicting the Phase Equilibria, Critical Phenomena, and Mixing Enthalpies of Binary Aqueous Systems Containing Alkanes, Cycloalkanes, Aromatics, Alkenes, and Gases (N2, CO2, H2S, H2) with the PPR78 Equation of State. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2013, 52, 16457–16490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloan, E.D., Jr. Fundamental Principles and applications of natural gas hydrates. Nature 2003, 426, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohebbi, V.; Naderifar, A.; Behbahani, R.M.; Moshfeghian, M. Determination of Henry’s law constant of light hydrocarbon gases at low temperatures. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 2012, 51, 8–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anil, J.V.; Bhawangirkar, D.R.; Sangwai, J.S. Effect of guest-dependent reference hydrate vapor pressure in thermodynamic modeling of gas hydrate phase equilibria, with various combinations of equations of state and activity coefficient models. Fluid Phase Equilib. 2022, 556, 113356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslamimanesh, A.; Mohammadi, A.H.; Richon, D. Thermodynamic model for predicting phase equilibria of simple clathrate hydrates of refrigerants. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2011, 66, 5439–5445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.; Pack, D.; Barifcani, A. Propane, n-butane and i-butane stabilization effects on methane gas hydrates. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 2017, 115, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Uchida, T.; Hayama, M.; Oshima, M.; Yamazaki, K. Nucleation probability of methane + propane mixed-gas hydrate depending on gas composition. Energy Fuels 2025, 39, 4782–4789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| i | a | b [K−1] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CH4 | ||||||

| C3H8 |

| i | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| CH4 | |||

| C3H8 |

| Small (512) | ||

| Large (51264) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Teraoka, T.; Sugibuchi, R.; Oshima, M.; Uchida, T. Modeling of Methane + Propane Mixed-Gas Hydrate Formation Processes in a Batch-Type Reactor Under Isothermal Condition. Processes 2026, 14, 261. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020261

Teraoka T, Sugibuchi R, Oshima M, Uchida T. Modeling of Methane + Propane Mixed-Gas Hydrate Formation Processes in a Batch-Type Reactor Under Isothermal Condition. Processes. 2026; 14(2):261. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020261

Chicago/Turabian StyleTeraoka, Takahiro, Ren Sugibuchi, Motoi Oshima, and Tsutomu Uchida. 2026. "Modeling of Methane + Propane Mixed-Gas Hydrate Formation Processes in a Batch-Type Reactor Under Isothermal Condition" Processes 14, no. 2: 261. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020261

APA StyleTeraoka, T., Sugibuchi, R., Oshima, M., & Uchida, T. (2026). Modeling of Methane + Propane Mixed-Gas Hydrate Formation Processes in a Batch-Type Reactor Under Isothermal Condition. Processes, 14(2), 261. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020261