Analysis of the Erosion Boundary of a Blast Furnace Hearth Driven by Thermal Stress Based on the Thermal–Fluid–Structural Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

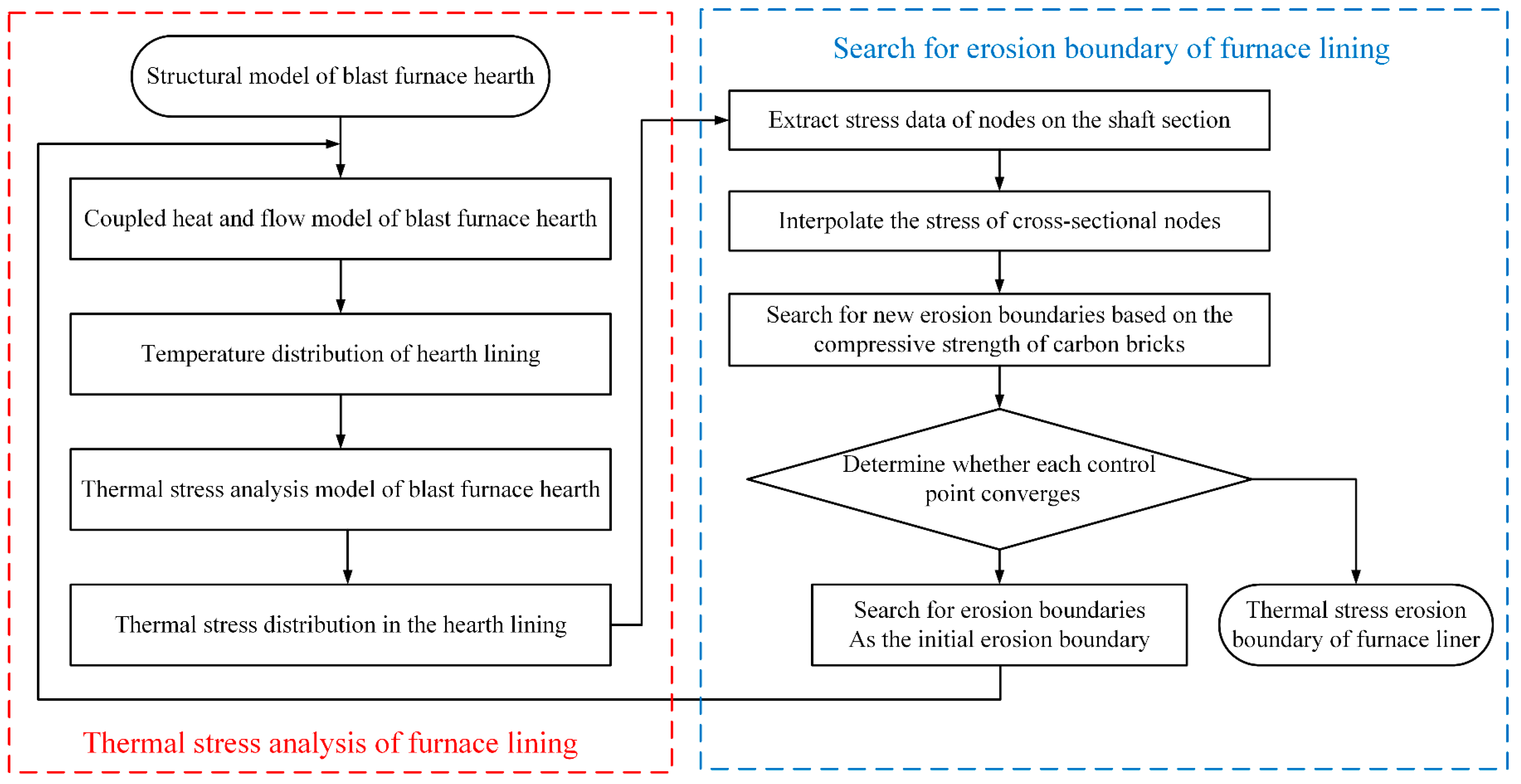

2.1. Thermal Stress Analysis Model of Hearth Lining

2.1.1. Physical Model

2.1.2. Mathematical Model

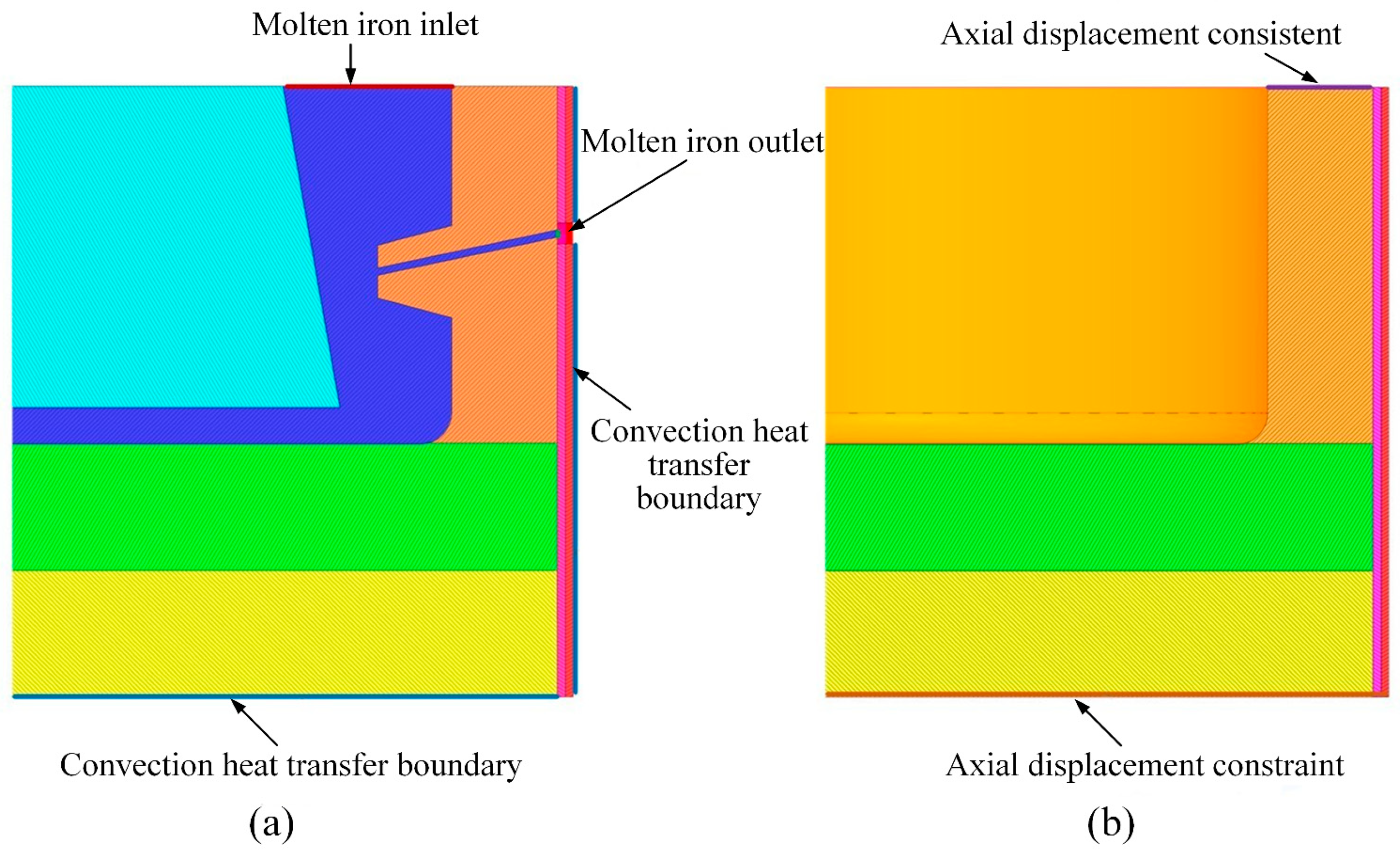

2.1.3. Boundary Conditions

2.1.4. Mesh Model

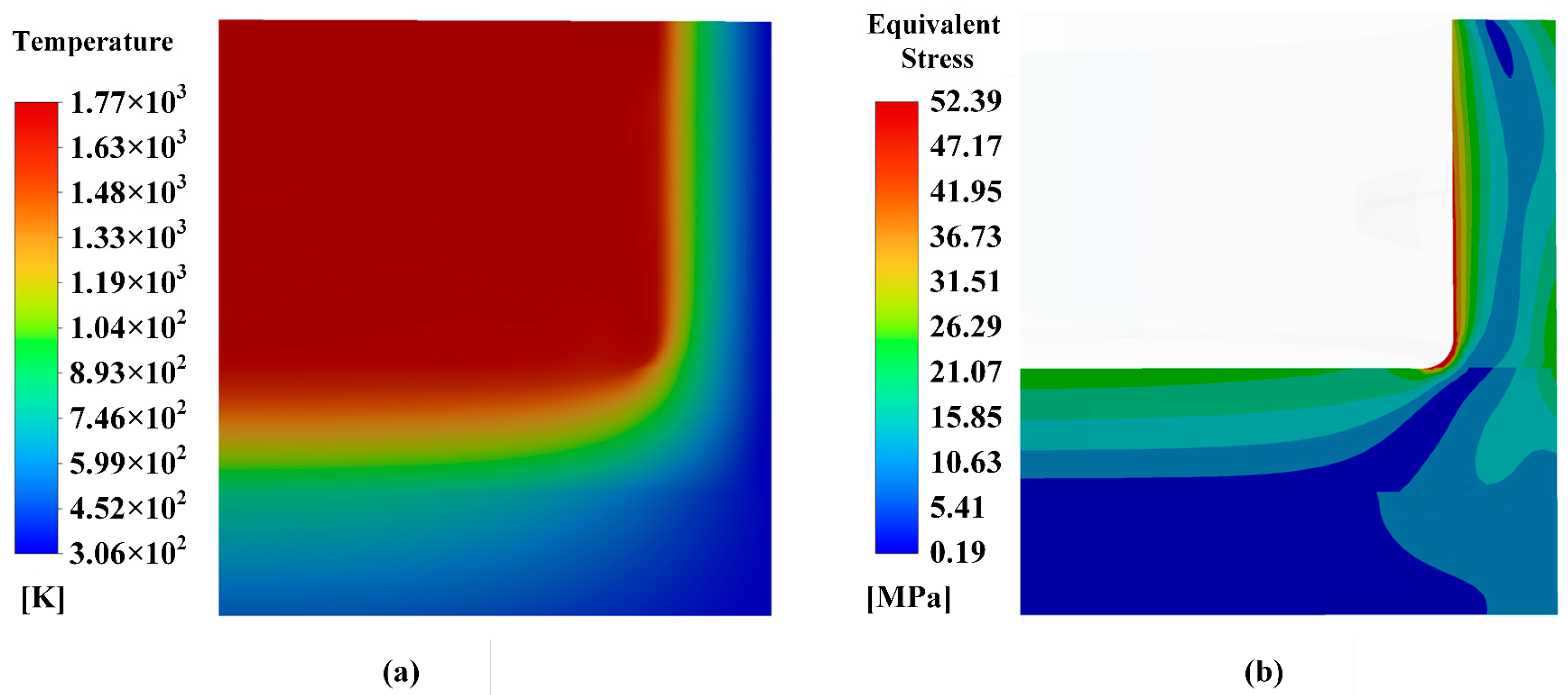

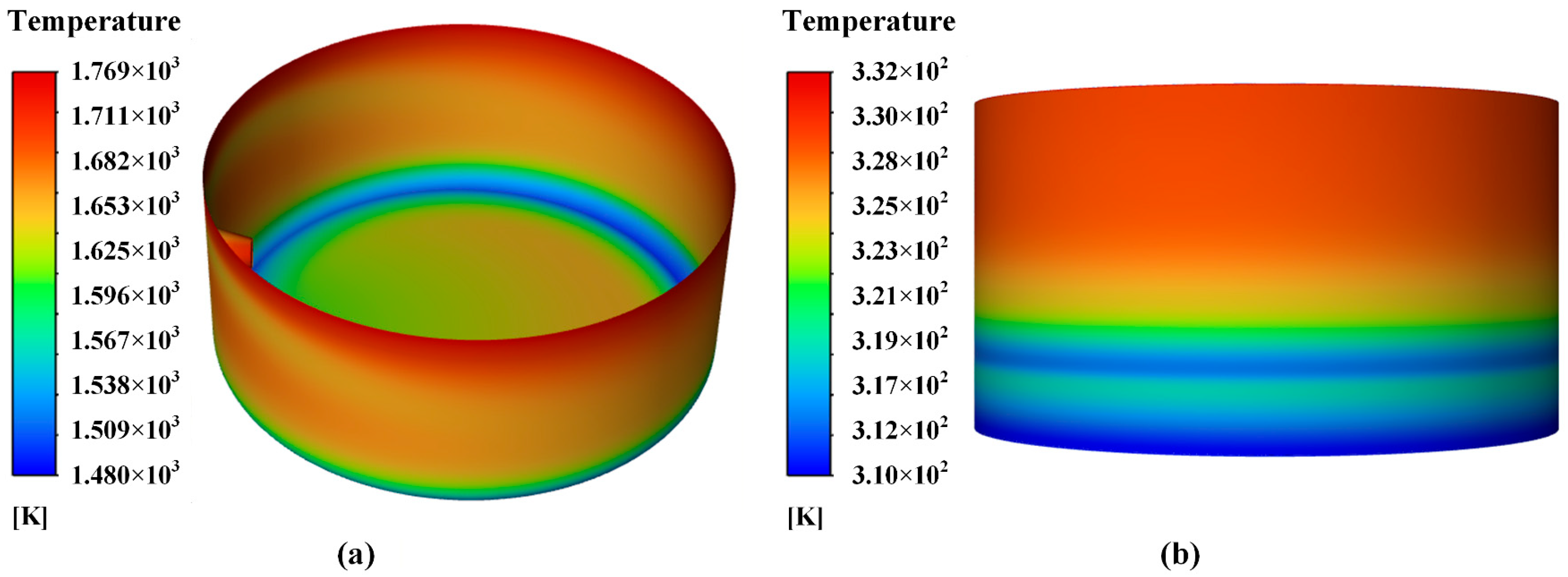

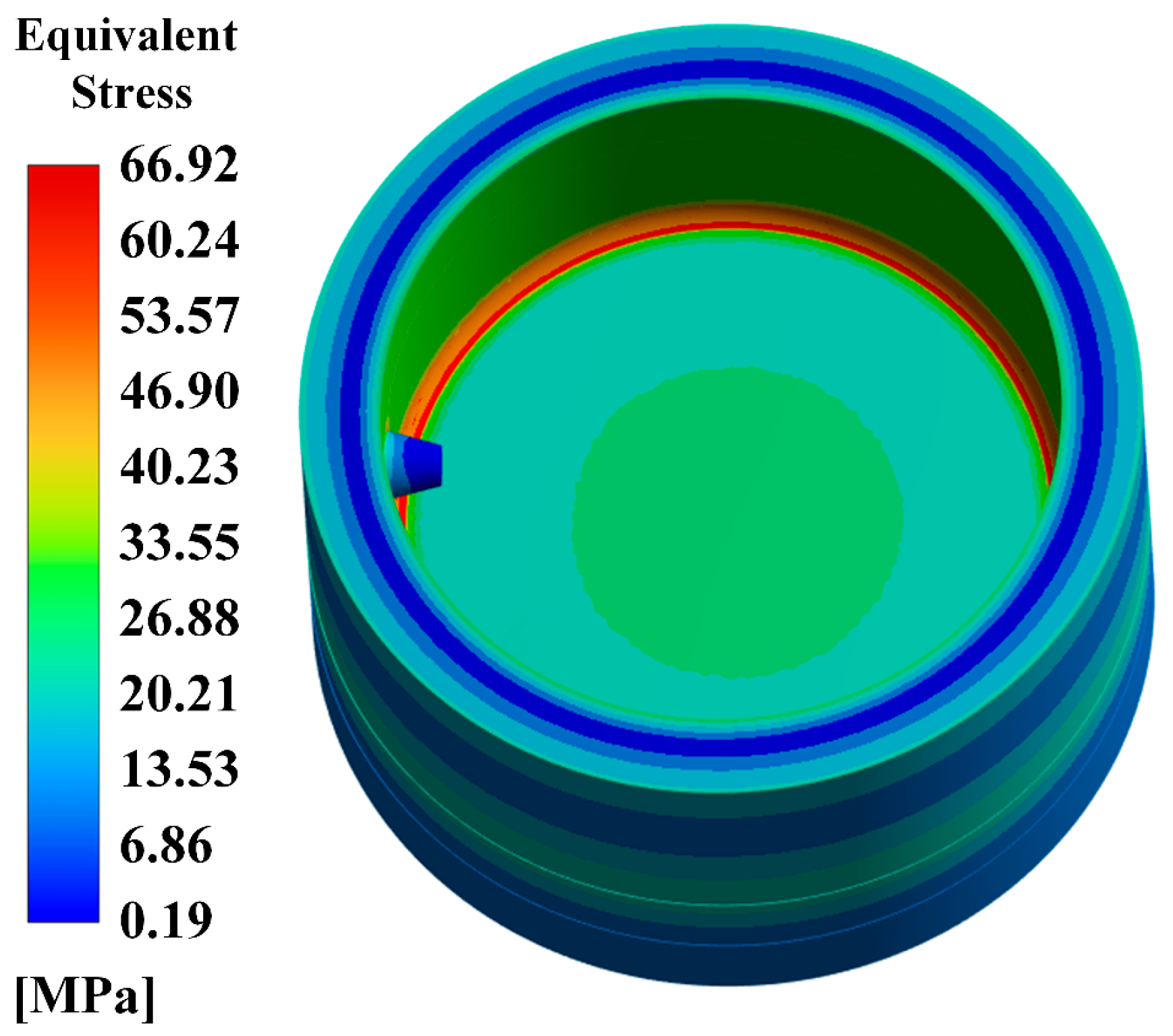

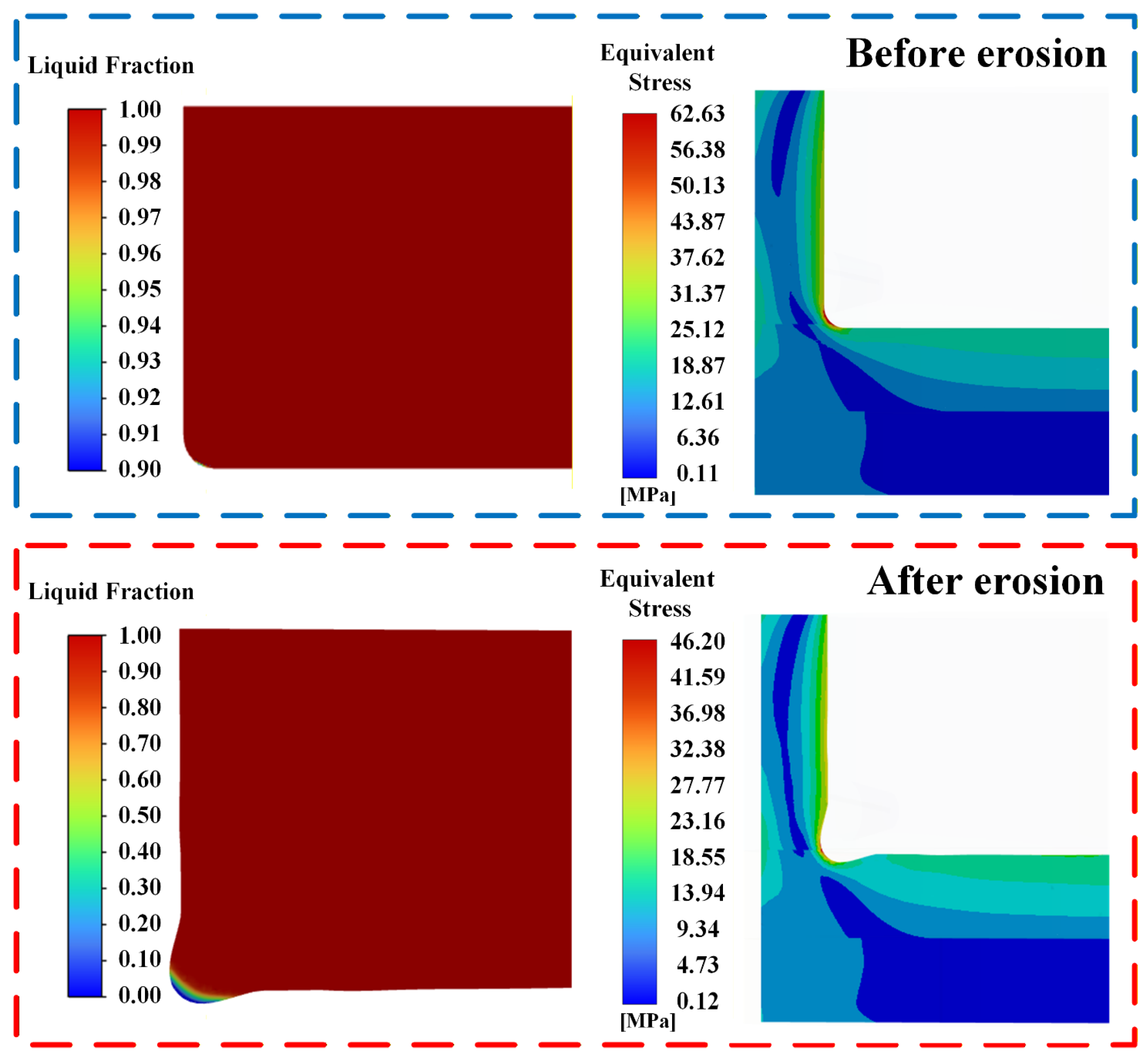

2.1.5. Results of Thermal–Fluid–Structural Coupling Model

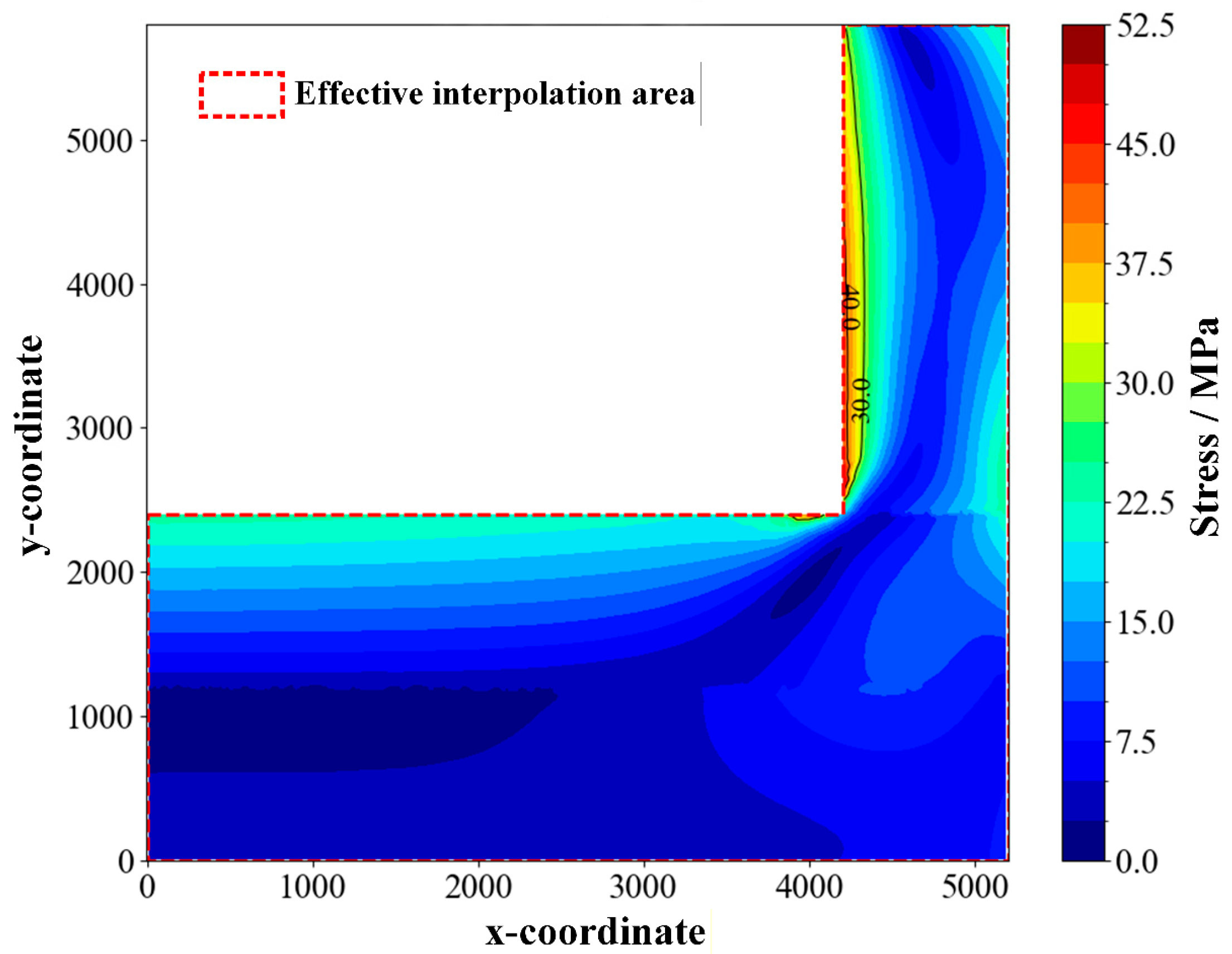

2.2. Search for Erosion Boundary Based on Lining Critical Strength

2.2.1. Search Method Description

2.2.2. Convergence Mechanism and Criterion

2.2.3. Validation of the Search Method

3. Results and Discussion

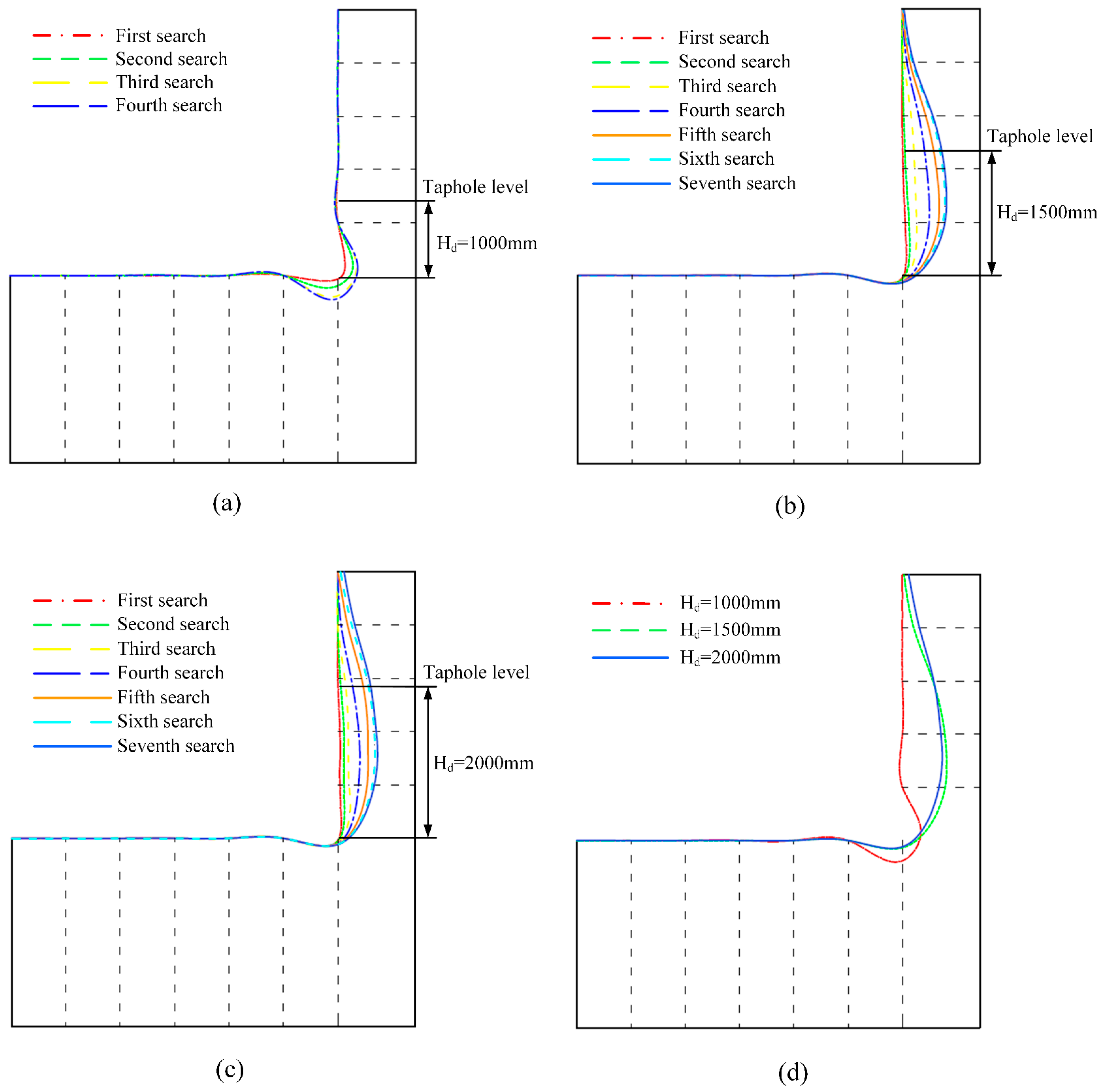

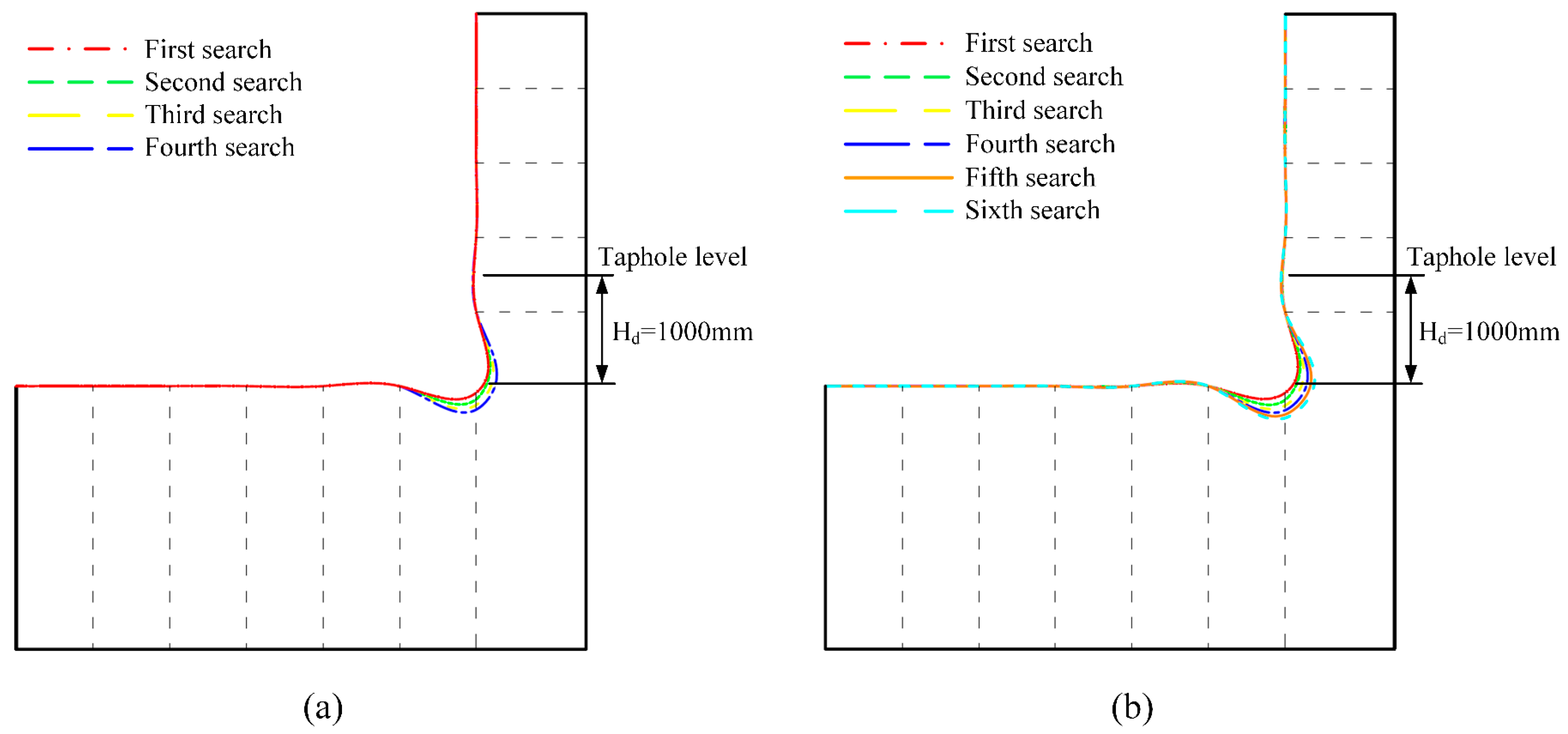

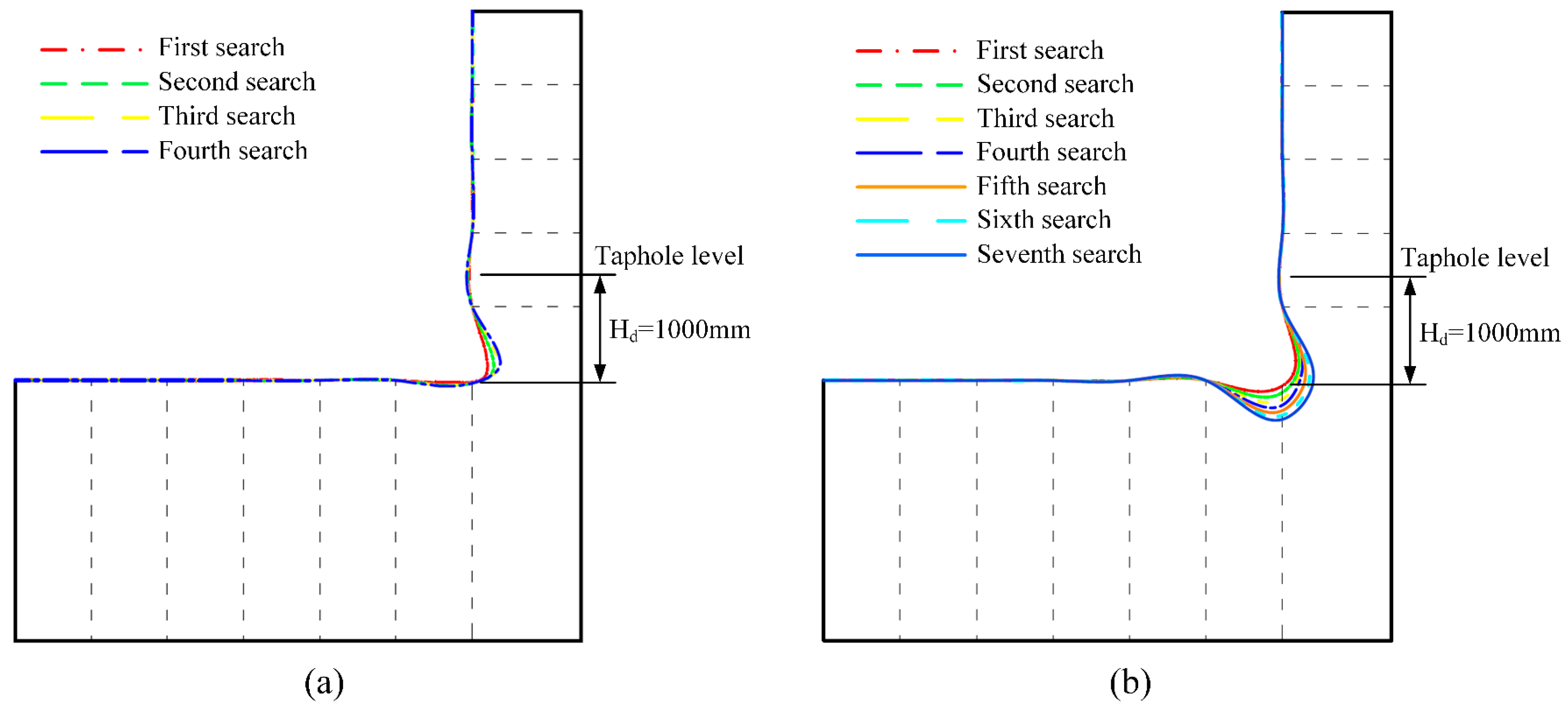

3.1. Dead Iron Layer Depth

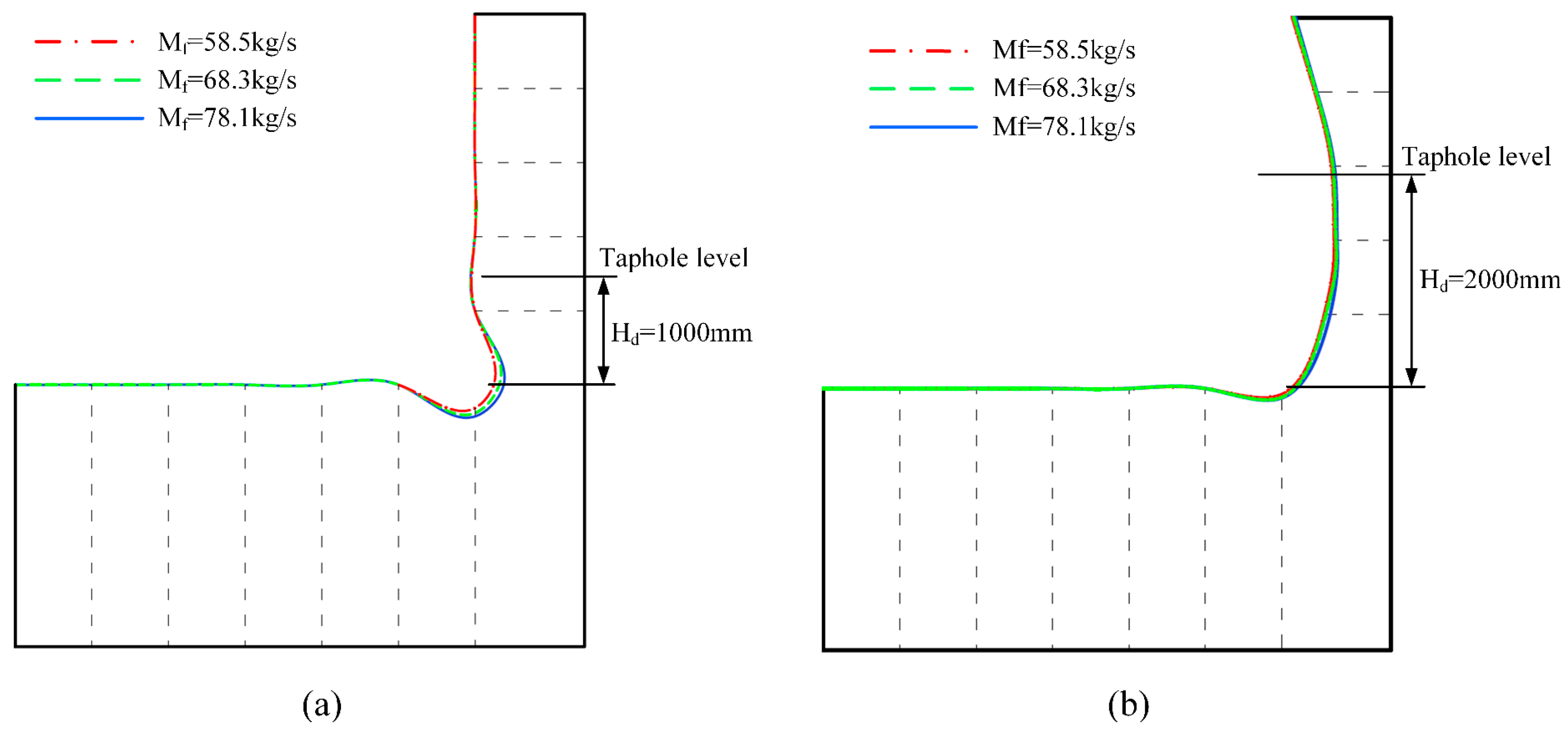

3.2. Tap Productivity

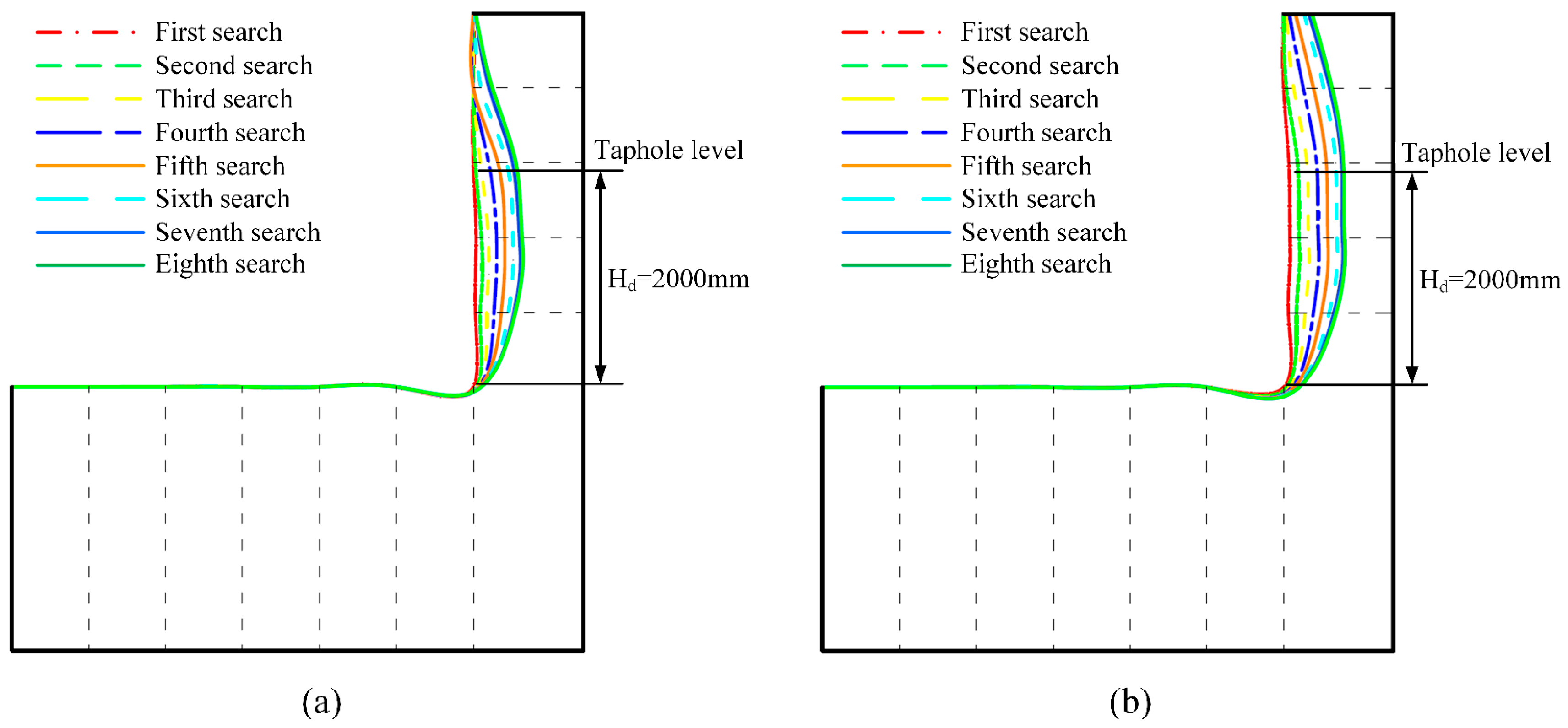

3.3. Molten Iron Temperature

4. Conclusions

- The dead iron layer depth is a key factor determining the erosion morphology. Its increase transforms the erosion from “elephant-foot-shaped” to “wide-face-shaped”, and the radial erosion depth first increases and then decreases. At depths of 1000 mm, 1500 mm, and 2000 mm, the maximum radial erosion depths are 251.28 mm, 571.73 mm, and 505.13 mm, respectively, with the most severe erosion moving upward as the depth increases.

- Increases in tapping productivity and molten iron temperature aggravate erosion without changing its basic type. When the productivity increases from 58.5 kg·s−1 to 78.1 kg·s−1, the radial erosion depth of the shallow dead iron layer increases by 54.0%, while that of the deep dead iron layer only increases by 6.3%. When the molten iron temperature rises from 1723 K to 1823 K, the radial erosion depths of the shallow and deep dead iron layer increase by approximately 15.8% and 23.9%, respectively.

- Under wide-face erosion, the axial position of the severely eroded zone is negatively correlated with tapping productivity and positively correlated with molten iron temperature.

- In the BF design, a reasonable and stable dead iron layer depth should be adopted to avoid severe concave erosion morphology. In operation, to ensure smooth furnace operation, the tapping productivity and molten iron temperature should be reasonably controlled to avoid long-term excessive values. Meanwhile, the growth of the solidified iron layer should be promoted to slow down the erosion process.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Constant | |

| Coke diameter, m | |

| Inner diameter of cooling water pipe, m | |

| Young’s modulus, Pa | |

| Search convergence criterion | |

| Gravitational acceleration, m·s−2 | |

| Turbulent kinetic energy generated by the mean velocity gradient, m2·s−3 | |

| Enthalpy, kJ·kg−1 | |

| Convective heat transfer coefficient on a plane surface, W·m−2·K−1 | |

| Species enthalpy, kJ·kg−1 | |

| Convective heat transfer coefficient on a cooling water pipe wall, W·m−2·K−1 | |

| Sensible enthalpy, kJ·kg−1 | |

| Convective heat transfer coefficient at the center of the cooling water pipe, W·m−2·K−1 | |

| Convective heat transfer coefficient on an inner cylindrical surface, W·m−2·K−1 | |

| Convective heat transfer coefficient on an outer cylindrical surface, W·m−2·K−1 | |

| Spacing between cooling water pipes, m | |

| Mass diffusion flux induced by concentration gradient, kg·m−2·s−1 | |

| Turbulent kinetic energy, m2·s−2 | |

| Latent heat of solidification, kJ·kg−1 | |

| Remaining lining thickness, m | |

| Daily output of molten iron, kg·d−1 | |

| Mass flow rate of molten iron, kg·s−1 | |

| Pressure, Pa | |

| Effective utilization coefficient, t·m−3·d−1 | |

| Inner diameter of the cylinder, m | |

| Outer diameter of the cylinder, m | |

| Source term | |

| Momentum source term of molten iron caused by deadman, kg·m−2·s−2 | |

| Temperature, K | |

| Initial temperature, K | |

| Solidus temperature, K | |

| Liquidus temperature, K | |

| Fluid velocity, m·s−1 | |

| Flow velocity of cooling water, m·s−1 | |

| Effective volume of BF, m3 | |

| Mass fraction | |

| Linear expansion coefficient, K−1 | |

| Shear strain components | |

| Latent enthalpy, kJ·kg−1 | |

| Control point moving distance, m | |

| Height difference, m | |

| Turbulent dissipation rate, m2⋅s−3 | |

| Normal strain components | |

| Effective thermal conductivity, W·m−1·K−1 | |

| Fluid thermal conductivity, W·m−1·K−1 | |

| Hearth lining thermal conductivity, W·m−1·K−1 | |

| Solid thermal conductivity, W·m−1·K−1 | |

| Molecular viscosity, Pa⋅s | |

| Poisson’s ratio | |

| Turbulent viscosity, Pa⋅s | |

| Effective viscosity, Pa⋅s | |

| Kinematic viscosity, Pa⋅s | |

| Density, kg⋅m−3 | |

| Shear stress components, Pa | |

| Normal stress components, Pa | |

| Prandtl number of k | |

| Prandtl number of ε | |

| Porosity | |

| Volume fraction |

References

- Liu, Y.X.; Jiao, K.X.; Zhang, J.L.; Wang, C.; Zhang, L.; Fan, X.Y. Research progress and future prospects in the service security of key blast furnace equipment. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 2024, 31, 2121–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, K.X.; Zhang, J.L.; Liu, Z.J.; Chen, C.L.; Liu, Y.X. Analysis of Blast Furnace Hearth Sidewall Erosion and Protective Layer Formation. ISIJ Int. 2016, 56, 1956–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.B.; Cheng, S.S.; Xue, Y.Q.; Cheng, X.M.; Liu, Z. Analysis of destructive effect of Zn on carbon brick and way of Zn into carbon brick. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2024, 31, 1344–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Jiao, K.X.; Zhang, J.L.; Wang, C.; Lei, M.; Shi, H.Y. Analysis of erosion morphology characteristics and mechanism of carbon brick in blast furnace hearth. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2025, 173, 109456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Zhang, J.L.; Wang, C.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, G.H.; Song, M.B. Erosion Mechanism of Carbon Brick in Hearth of 4000 m3 Industrial Blast Furnace. Metals 2023, 13, 1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, K.K.; Wang, J.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Fu, T. Erosion Behavior and Longevity Technologies of Refractory Linings in Blast Furnaces for Ironmaking: A Review. Steel Res. Int. 2022, 93, 2200266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blond, E.; Nguyen, A.K.; de Bilbao, E.; Sayet, T.; Batakis, A. Thermo-chemo-mechanical modeling of refractory behavior in service: Key points and new developments. Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 2020, 17, 1693–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaymak, Y.; Bartusch, H.; Hauck, T.; Mernitz, J.; Rausch, H.; Lin, R.S. Multiphysics Model of the Hearth Lining State. Steel Res. Int. 2020, 91, 2000055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.C.; Wen, X.W.; Zhao, X. Detection of Blast Furnace Hearth Lining Erosion by Multi-Information Fusion. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 106192–106201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.T.; Yang, T.; Yan, R.; Zhao, H.B. Anomaly detection of the blast furnace smelting process using an improved multivariate statistical process control model. Process Saf. Environ. Protect. 2022, 166, 617–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perepelitsyn, V.A.; Zemlyanoi, K.G.; Ust’yantsev, V.M.; Mironov, K.V.; Forshev, A.A.; Nikolaev, F.P.; Sushnikov, D.V. Material Substance Composition and Microstructure of the Ceramic Hearth of Blast Furnace No. 6 EVRAZ NTMK After Service. Part 1. Refractory Mineral Composition. Refract. Ind. Ceram. 2022, 63, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barral, P.; Perez-Perez, L.J.; Quintela, P. Transient 3D hydrodynamic model of a blast furnace main trough. Eng. Appl. Comp. Fluid Mech. 2023, 17, 2280776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.L.; Cheng, S.S.; Zhang, P.; Zhou, S.H. Sensitive Influence of Floating State of Blast Furnace Deadman on Molten Iron Flow and Hearth Erosion. ISIJ Int. 2015, 55, 2332–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, A.; Li, C.Z.; Zhang, W.; Xiao, Z.X.; Liu, D.L.; Xue, Z.L. Investigation of the Hearth Erosion of WISCO No. 1 Blast Furnace Based on the Numerical Analysis of Iron Flow and Heat Transfer in the Hearth. Metals 2022, 12, 843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, K.C.; Wen, Z.; Liu, X.L.; Ren, Y.Q.; Wu, W.F.; Qiu, H.B. Research Status and Development Trend of Numerical Simulation on Blast Furnace Lining Erosion. ISIJ Int. 2009, 49, 1277–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.B.; Hou, B.B.; Shao, L.; Zou, Z.S.; Saxén, H. Estimation of the Blast Furnace Hearth State Using an Inverse-Problem-Based Wear Model. Metals 2022, 12, 1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helle, M.; Saxén, H.; de Graaff, B.; van der Bent, C. Wear-Model-Based Analysis of the State of Blast Furnace Hearth. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2022, 53, 594–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.Q.; Shao, L.; Zou, Z.S.; Saxén, H. Asymptotic Model of Refractory and Buildup State of the Blast Furnace Hearth. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2022, 53, 320–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.G.; Chen, L.Y.; Xu, J.W. Mechanical Model and Calculation of Dry Masonry Brick Lining of Blast Furnace Hearth. ISIJ Int. 2018, 58, 1191–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brulin, J.; Gasser, A.; Rekik, A.; Blond, E.; Roulet, F. Thermomechanical modelling of a blast furnace hearth. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 326, 126833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.C.; Ma, K.Y.; Wei, Z.F.; Cai, Q.X.; Huang, X.Y.; Qiu, S.X.; Wen, L.Y.; Zhang, S.F. Three-dimensional numerical simulation analyses for heat transfer and thermal stress in blast furnace hearth lining with different refractory masonry methods. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2025, 39, 4747–4764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Wang, C.; Zhang, J.L.; Yang, X.T.; Xu, J.; Zhang, G.H. Formation Mechanism of the Brittle Layer in Carbon Brick of Blast Furnace Hearth. Steel Res. Int. 2023, 94, 2300168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, K.X.; Wang, C.; Zhang, J.L.; Ren, S.; Dian-Yu, E. Heat Transfer Evolution Process in Hearth Based on Blast Furnace Dissection. JOM 2020, 72, 1935–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chen, L.Y.; Yuan, F.; Zhao, L.; Li, Y.; Ma, J.C. Thermal Stress Analysis of Blast Furnace Hearth with Typical Erosion Based on Thermal Fluid-Solid Coupling. Processes 2023, 11, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.F.; Zulli, P. Prediction of blast furnace hearth condition: Part I—A steady state simulation of hearth condition during normal operation. Ironmak. Steelmak. 2020, 47, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.; Chen, L.Y.; Wang, L.; Zhao, L.; Zhong, Y. Study on the Effect of Deadman State on Blast Furnace Hearth Erosion Based on Solidification and Melting Model. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 21811–21826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.Q.; Shao, L.; Saxén, H. Numerical Analysis of Blast Furnace Hearth Drainage Based on a Simulated Hele-Shaw Model. Steel Res. Int. 2022, 93, 2100629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.T.; Huang, E.N.; Du, S.W. Numerical analysis on transient thermal flow of the blast furnace hearth in tapping process through CFD. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2014, 57, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, P.C.; Du, S.W.; Liu, S.H.; Cheng, W.T. Numerical investigation on effects of cooling water temperature and deadman status on thermal flow in the hearth of blast furnace during tapping shutdown. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2021, 23, 100908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kambampati, S.; Kim, H.A. Level set topology optimization of cooling channels using the Darcy flow model. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 2020, 61, 1345–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, T.W.; Liu, X.Y.; Xue, S.; Xu, J.M.; He, M.G.; Zhang, Y. Extension of Ergun equation for the calculation of the flow resistance in porous media with higher porosity and open-celled structure. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2020, 173, 115262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, P.R. Enthalpy porosity model for melting and solidification of pure-substances with large difference in phase specific heats. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2017, 81, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.F.; Zulli, P.; Tsalapatis, J.; Middleton, M. Operational application of numerical modelling for evaluation of hearth condition over a blast furnace campaign: Whyalla No. 2 Blast Furnace 4th campaign. Ironmak. Steelmak. 2022, 49, 860–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.Y.; He, Z.Y.; Liu, S.C.; Zeng, B. MMSE-Directed Linear Image Interpolation Based on Nonlocal Geometric Similarity. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2017, 24, 1178–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, M.X.; Chen, R.; Li, Q. Development of erosion monitoring model for blast furnace hearth based on moving-boundary method. Mater. Res. Innov. 2015, 19, 448–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Property | Density /kg·m−3 | Specific Heat Capacity /J·kg−1·K−1 | Thermal Conductivity /W·m−1·K−1 | Young’s Modulus /GPa | Poisson’s Ratio | Thermal Expansion Coefficient /10−6·K−1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GB | 1780 | 840 | 46.61 − 0.01342 T | 7.9 | 0.15 | 2.16 |

| MCB | 1620 | 840 | 8.88 + 0.0044 T | 7.9 | 0.15 | 2.84 |

| UMCB | 2150 | 840 | 13.58 + 0.005 T | 7.9 | 0.15 | 3.38 |

| Ramming mass | 1650 | 876 | 12.5 | 15 | 0.1 | 3 |

| Shell | 7840 | 465 | 48 | 200 | 0.3 | 5.87 |

| Density /kg·m−3 | Specific Heat Capacity /J·kg−1·K−1 | Thermal Conductivity /W·m−1·K−1 | Viscosity /kg·m−1·s−1 | Latent Heat /J·kg−1 | Solidification Temperature /K | Melting Temperature /K |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6700 | 756 | 0.0158 T | 0.007 | 103,343 | 1423 | 1573 |

| Temperature Monitoring Point | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | T5 | T6 | T7 | T8 | T9 | T10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measured/K | 1136.8 | 645.9 | 784.2 | 576.4 | 639.3 | 713.4 | 759.8 | 768.5 | 723.7 | 716.8 |

| Measured/K | 1113.2 | 667.6 | 804.2 | 599.7 | 668.2 | 739.6 | 788.3 | 796.5 | 747.9 | 736.6 |

| Error/% | 2.08 | 3.35 | 2.55 | 4.04 | 4.53 | 3.67 | 3.75 | 3.64 | 3.34 | 2.76 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yuan, F.; Chen, L.; Wang, L.; Zhao, L.; Li, Z. Analysis of the Erosion Boundary of a Blast Furnace Hearth Driven by Thermal Stress Based on the Thermal–Fluid–Structural Model. Processes 2026, 14, 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010019

Yuan F, Chen L, Wang L, Zhao L, Li Z. Analysis of the Erosion Boundary of a Blast Furnace Hearth Driven by Thermal Stress Based on the Thermal–Fluid–Structural Model. Processes. 2026; 14(1):19. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010019

Chicago/Turabian StyleYuan, Fei, Liangyu Chen, Lei Wang, Lei Zhao, and Zhuang Li. 2026. "Analysis of the Erosion Boundary of a Blast Furnace Hearth Driven by Thermal Stress Based on the Thermal–Fluid–Structural Model" Processes 14, no. 1: 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010019

APA StyleYuan, F., Chen, L., Wang, L., Zhao, L., & Li, Z. (2026). Analysis of the Erosion Boundary of a Blast Furnace Hearth Driven by Thermal Stress Based on the Thermal–Fluid–Structural Model. Processes, 14(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010019