Abstract

Accurate and rapid fault diagnosis is paramount to stabilizing proton exchange membrane fuel cells (PEMFC). To achieve this, this study proposes a novel fault diagnosis method that integrates a convolutional neural network (CNN), a bi-directional long short-term memory network (BiLSTM), and a waveform fault attention (WFA) mechanism. In the proposed framework, data are classified into five distinct categories utilizing a hierarchical clustering algorithm. Additionally, data augmentation techniques are implemented to bolster model performance. The introduction of amplitude attention and temporal difference attention, in conjunction with the construction of WFA, enables the accurate extraction of temporal-spatial features, significantly improving the distinguishability of fault diagnosis. Furthermore, feature contribution is evaluated using permutation feature importance (PFI) to identify key features, enhancing the interpretability of the model. Experimental findings verify that the proposed method enables high-precision fault identification, with precision values spanning 97–100% and an average stability of 98.3%, demonstrating robust performance even when the volume of original sample data is limited. This performance markedly surpasses that of extant methodologies. The comprehensive approach augments the accuracy, reliability, and interpretability of PEMFC fault diagnosis, and introduces a novel research paradigm for feature extraction, thereby possessing significant theoretical and practical application value.

1. Introduction

The pursuit of eco-friendly, high-efficiency, and long-lasting energy alternatives [1,2,3] has become a crucial issue for modern society, driven by the escalating global energy crisis [4,5] and environmental pollution [6,7]. In this context, fuel-cell technology has attracted substantial attention on account of its high-efficiency and zero-emission characteristics. Among various fuel-cell types, proton exchange membrane fuel cells (PEMFC) have shown extensive application prospects in the domains of transportation [8] and stationary power generation [9]. This can be ascribed to their high-power density, low operating temperature, and the characteristic of being pollutant-free [10,11]. However, despite the numerous advantages of PEMFCs, the complexity of their operating environment and the variability of their operating conditions pose significant challenges, leading to issues of low reliability and poor durability in practical applications. These issues not only affect the performance of the PEMFC system but can also reduce its operational lifespan, thereby impeding its industrialization. In order to improve the reliability and longevity of PEMFCs, fault diagnosis technology has become a key area of research [12]. Fault diagnosis is not only capable of timely detecting abnormalities within the system but also provides a foundation for faulty localization and troubleshooting, thereby ensuring the safe operation of the system [13,14]. Notably, fault diagnosis constitutes merely one core module within the broader prognostics and health management (PHM) framework [15]-a paradigm that integrates real-time monitoring, fault diagnosis, and health state estimation, alongside remaining useful life (RUL) prediction [16], to establish a closed-loop reliability management system for energy devices. Currently, PEMFC fault diagnosis approaches are mainly classified into two categories [17]: diagnosis methods based on models [18] and diagnosis methods driven by data [19]. Model-based methodologies hinge on the construction of precise mathematical models to forecast and emulate the performance of systems. Nevertheless, in light of the pronounced nonlinearity inherent in PEMFC systems and the intricacy of their electrochemical characteristics, the development of an all-encompassing model that accommodates all conceivable faults presents an exceptionally formidable challenge. Conversely, data-driven diagnostic approaches, which scrutinize operational data of the system to discern faults, exhibit enhanced flexibility and adaptability. As a result, they are more extensively utilized in the realm of PEMFC fault diagnosis.

The emergence of machine learning has exerted a significant influence on the utilization of deep learning techniques in the context of PEMFC fault diagnosis. For instance, ref. [20] put forward a deep learning-based data-driven approach for PEMFC, which selects suitable diagnostic metrics by combining the water transport mechanism and auxiliary systems, constructing a fault diagnosis model using convolutional neural network (CNN) after converting the data into a two-dimensional image and enhancing the model’s generalization capability through batch normalization. Similarly, ref. [21] constructed a pre-diagnostic model using a long short-term memory network (LSTM) and CNN, which was combined with integrated learning (bagging) to improve the detection performance of flooding and drying faults. Inc-DenseNet proposed in [22] significantly improves diagnostic performance by extracting robust features from battery voltages through a densely connected structure. In [23], LSTM-based online diagnostic model has been proposed, obviating the need for extensive sensor installation by utilizing system state inputs [24]. Utilized a multilayer perceptron model in conjunction with a back-propagation algorithm to optimize the PEMFC impedance model and effectively predict electrochemical impedance parameters. A multi-scale convolutional neural network (MCNN) was proposed in [25], which demonstrated high accuracy in the recovery and identification of fatal faults, as well as multi-fault diagnosis. The article [26] presented higher accuracy and the ability to generalize, based on one-dimensional convolutional neural networks (1DCNN) and XGBoost (1DCNN-XGB), for hierarchical fault diagnosis. Furthermore, the binary matrix coded neural network (BinE-CNN), as outlined in [27], has been shown to achieve seven classes of fault classification while meeting the real-time and accuracy requirements. In short, these studies represent a significant advancement in the current state of PEMFC fault-diagnosis technology development.

Existing fault diagnosis technologies for PEMFCs primarily rely on machine learning methods and often integrate hybrid algorithms to enhance diagnostic accuracy or develop innovative models. However, two prominent issues warrant particular attention. As an increasingly common component in such technologies-the attention mechanism-its practical application further exposes inherent limitations. Currently, basic attention mechanisms widely used in this field typically focus on one-dimensional feature weighting, making it difficult to effectively capture the intrinsic correlations between the spatial distribution and temporal variations in fault signals [28]. Meanwhile, although multi-scale attention mechanisms have achieved some progress in addressing feature-scale discrepancies, they still fail to achieve collaborative fusion of spatiotemporal information, resulting in fragmented feature extraction [29]. To address these shortcomings, this study proposes a spatiotemporal waveform fault attention (WFA) mechanism that enables simultaneous extraction and adaptive weighting of spatiotemporal features [30], thereby overcoming the limitations of conventional basic and multi-scale attention mechanisms. Furthermore, existing technologies exhibit significant deficiencies in spatiotemporal feature utilization, model interpretability, and dynamic feature extraction, all of which demand further optimization and improvement. To overcome these challenges, this research introduces a new approach for constructing a PEMFC data-driven fault diagnosis framework. The proposed framework integrates the spatiotemporal waveform attention mechanism into a convolutional neural network-bidirectional long short-term memory-waveform fault attention (CNN-BiLSTM-WFA) architecture and employs the permutation feature importance (PFI) method to perform interpretability analysis. The main contributions of this study can be summarized as follows:

- (1)

- Classifying the data into five categories using a hierarchical clustering algorithm and incorporating data enhancement techniques to effectively improve model performance.

- (2)

- Constructing a WFA by employing amplitude attention and temporal difference attention to accurately extract temporal-spatial features and provide discriminative information for fault diagnosis.

- (3)

- Utilizing a CNN-BiLSTM-WFA model to achieve high-precision fault identification under small sample sizes and unknown conditions.

- (4)

- Evaluating parameter contribution through PFI, screening key features, enhancing model interpretability, and reducing sensor redundancy and computational cost.

2. Model and Battery Dataset Analysis

2.1. Fault Diagnosis for PEMFC System

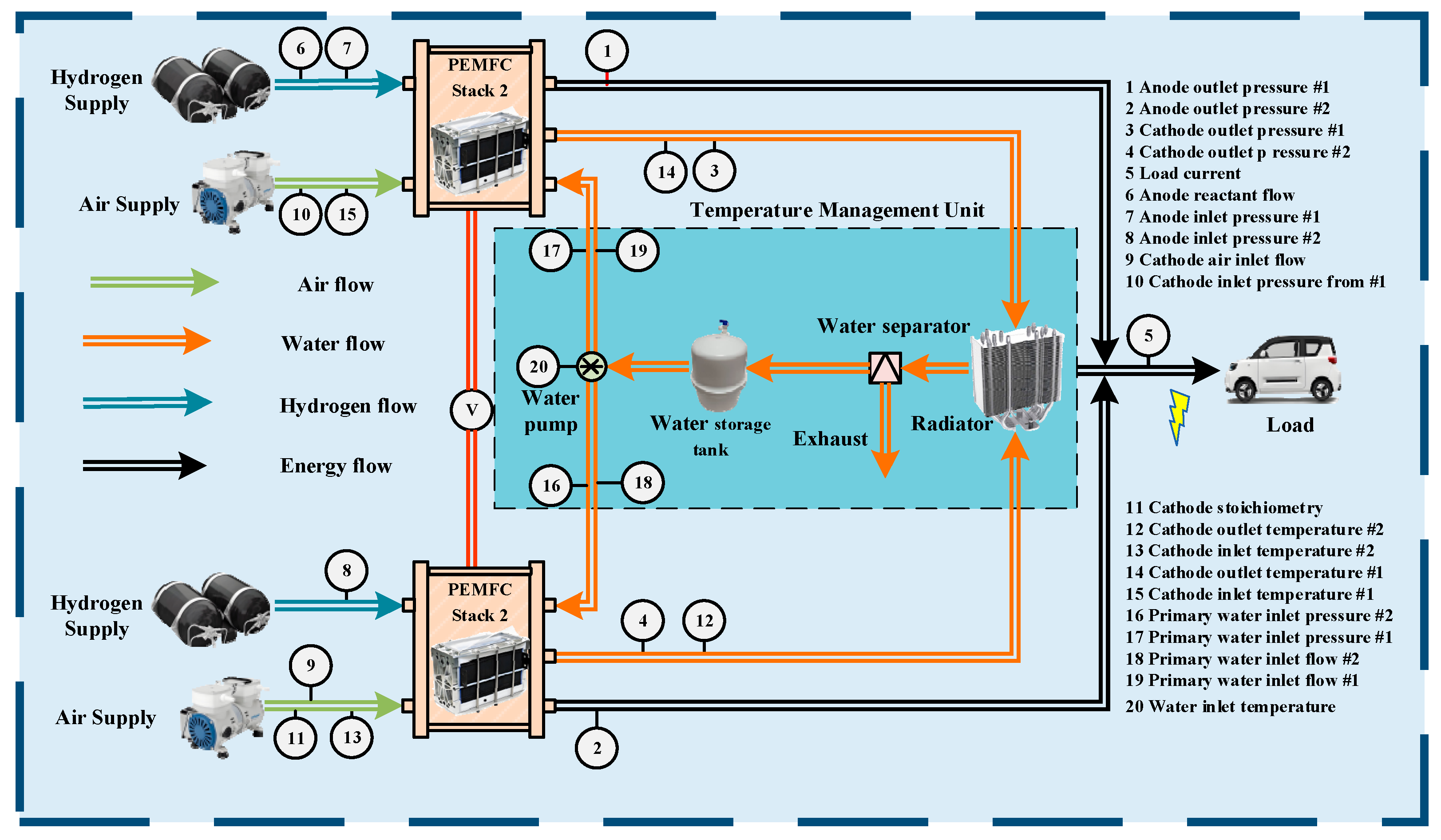

The PEMFC system can effectively transform the chemical energy of hydrogen into electrical energy. It consists of a PEMFC stack, a hydrogen supply unit, an air supply unit, and a temperature management unit. These components operate in synergy to guarantee that the system can deliver power to the loads in a continuous and stable manner. During the operation, the system allows hydrogen and air to enter PEMFC stack via the corresponding hydrogen and air supply units. The temperature management unit is responsible for maintaining the stack at an optimal operating temperature range, thereby optimizing performance and efficiency.

Nevertheless, because of the intrinsic dynamic characteristic of PEMFC operation, a variety of problems, such as flooding, drying, and gas starvation, are often faced [31,32]. The occurrence of these failures can lead to a decrease in PEMFC performance. It might cause permanent damage to the battery pack and significantly shorten its lifespan. Among the most common types of failures observed in PEMFC systems are membrane drying [33] and hydrogen leakage [34]. The etiologies of these failures can be broadly classified into two primary categories: intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Intrinsic factors predominantly influence the operational parameters within PEMFC, whereas extrinsic factors are intimately associated with the external environment and the operational conditions of the system.

Water management is critically important for ensuring the optimal operation of PEMFC. A suitable amount of water is crucial for keeping the proton-exchange membrane in a hydrated state. This, in return, guarantees the best possible proton conductivity and the overall performance of the cell. In PEMFC, the main ways of water transfer are thermal permeation, electromigration, concentration diffusion, and pressure permeation. These procedures have a direct impact on the water content within the membrane. When the rate of water removal surpasses the rate of water production, the membrane may become desiccated, resulting in an augmentation of membrane resistance and an escalation in heat generation, thereby diminishing the efficiency of the cell.

Beyond the macro-scale water management behaviors and fault mechanisms discussed earlier, the microscale dynamic characteristics of liquid water in the gas diffusion layer are closely correlated with water-related faults such as membrane drying and flooding. The lattice Boltzmann method is a well-established numerical tool for investigating microscale liquid water transport in gas diffusion layers with gradient porosity, which enables quantitative analysis of the correlation between their structural parameters and water management performance. The porosity distribution of gas diffusion layers and the structural changes induced by compression directly govern water removal efficiency; ineffective water drainage caused by mismatched porosity gradients or excessive compression is likely to block gas diffusion pathways (triggering flooding) or disrupt the membrane hydration balance (inducing membrane drying) [35].

Hydrogen leakage is another common failure in PEMFC systems, with primary causes including seal failure, material defects, operational errors, and environmental factors. This holistic comprehension of the factors influencing PEMFC performance accentuates the significance of efficacious fault diagnosis and management strategies to augment the reliability and service life of these systems.

2.2. Data Analysis

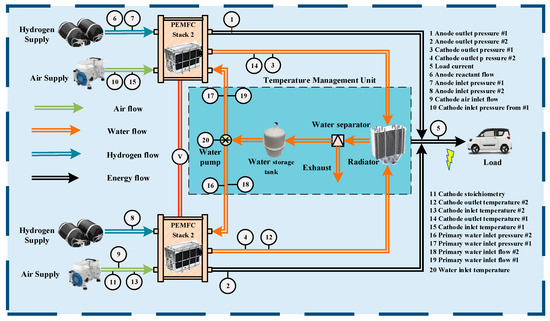

2.2.1. Data Classification

The data utilized in this study were sourced from a dataset published in the Loughborough University Research Repository [36], which is associated with the field of PEMFC system fault diagnosis. The experimental setup adopted an evaporatively cooled PEMFC system, which is specifically designed for high-volume, low-cost manufacturing scenarios and achieves stack heat dissipation by utilizing vaporization heat. This system comprises two fuel cell stacks, with each stack integrating 300 individual fuel cell units, and the overall power output of the system can reach 100 kW. During operation, hydrogen is supplied to the anode and air to the cathode of the system, while water is injected simultaneously to realize humidification and heat dissipation. In terms of data acquisition, the system’s sampling frequency was set at 1 Hz, and the measurement data of each sensor contained 300 sample points. A total of 20 state parameters were recorded during the monitoring process. For detailed information regarding the sensor types, units, and installation positions, refer to Figure 1 of the original paper.

Figure 1.

The schematic of PEMFC system.

This dataset encompasses a total of 61 sets of operational condition data, which were categorized by researchers into three distinct operational states-normal, unknown, and faulty-based on load current characteristics and fault occurrence status. Among them, the normal state includes 25 sets of data, characterized by stable load current and the absence of any system faults, serving as a typical representation of the stable and healthy operation of PEMFC system. The faulty state consists of 11 sets of data, exhibiting transient load current fluctuations and confirmed system faults; specifically, it covers two typical fault types, namely membrane drying faults and hydrogen supply abnormalities, which are identified by the system’s dedicated fault indicators. The unknown state also comprises 25 sets of operational conditions, whose core feature is the presence of significant transient load current fluctuations without triggering any system fault alarms, meaning it essentially falls within the scope of the fuel cell’s healthy operation. Owing to the high similarity between its transient load response characteristics and those of the faulty state, the unknown state is prone to being misclassified as a faulty state during diagnostic processes. This unique attribute renders it a critical operational condition for verifying the robustness and discriminative ability of fault diagnosis methods.

In the analysis of the fault states of PEMFC system, this study computes the mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) of the 20 parameters, averaged across the fault states, utilizing the average values of the steady-state parameters under normal operating conditions. MAPE is calculated as

where the notation is employed to denote the observed value of the i-th parameter in a normal steady state, is used to denote the observed value of the i-th parameter in a faulty state, and is used to denote the total number of parameters. MAPE metrics can effectively quantify the deviation of the faulty state from the normal state. MAPEs for the 20 parameters of the four types are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

MAPE distributions for faults and unknowns.

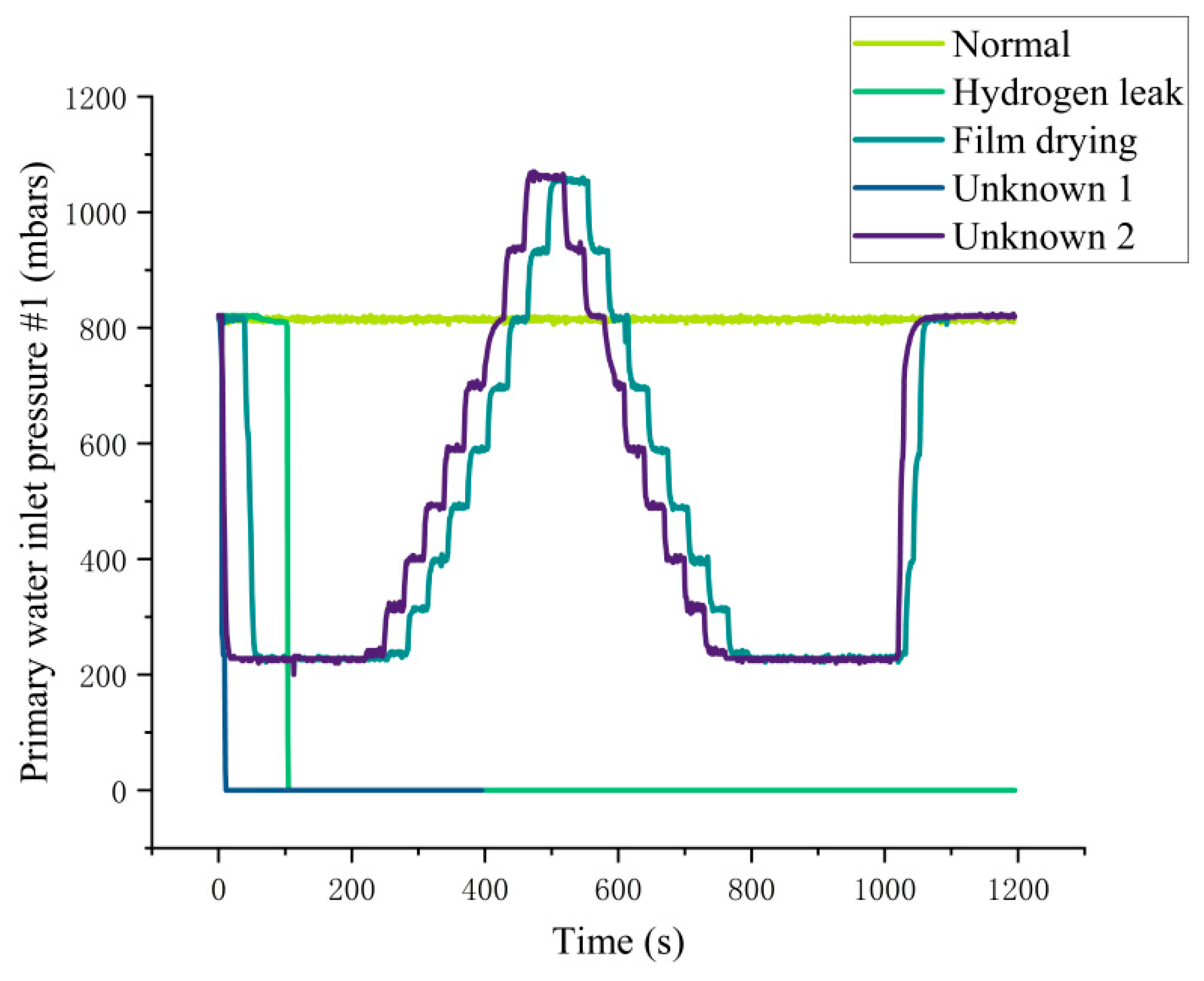

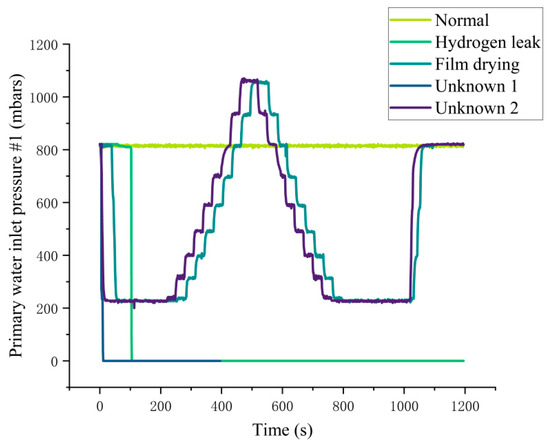

Membrane drying problems usually have harmful impacts on all the parameters related to water inlets. Since maintaining the membrane in a wet state is vital for the efficient operation of the system, this study centers on four key parameters. These are the main water inlet pressure of stack 2, the main water inlet pressure of stack 1, the main water inlet flow of stack 2, and the main water inlet flow of stack 1. The application of a hierarchical clustering algorithm successfully categorized fault states into membrane drying and hydrogen leakage, while normal transients were categorized as unknown 1 and unknown 2.

Normal transient states are induced by factors such as load fluctuations, temperature variations, and the dynamic characteristics of internal chemical reactions. It is worth noting that although the data categorized as “unknown” exhibit fault-like characteristics, they are actually associated with the healthy operational state of the system. As illustrated in Figure 2, the waveforms of the primary water inlet pressure of stack 1 for the five types of data are presented. It can be clearly observed from Figure 2 that the waveforms of unknown category 1 are similar to those of hydrogen leakage, while the waveforms of unknown category 2 share characteristic similarities with membrane drying. Specifically, Unknown1 is triggered by a large load step increase, with its core parameter fluctuations concentrated in the hydrogen/air supply subsystem, thus resulting in waveforms similar to hydrogen leakage; Unknown2 is triggered by the start-stop operation of the cooling water circuit pump, with parameter fluctuations concentrated in the water management subsystem, hence its waveforms approaching those of membrane drying. However, the characteristics of fault signals caused by transient currents differ significantly from those of normal states, enabling the differentiation between normal and faulty conditions. Nevertheless, in practical applications, distinguishing between unknown categories and actual fault conditions remains a formidable challenge, mainly due to the presence of transient load currents in the unknown data, which can mimic fault behaviors. This challenge will bring about prominent engineering negative impacts on PEMFC fault diagnosis in multiple dimensions: on the one hand, it will trigger a high risk of misdiagnosis, where the parameter fluctuations of the hydrogen/air supply subsystem in Unknown State 1 are prone to being misjudged as hydrogen leakage faults by traditional diagnostic models, leading to unnecessary hydrogen loop maintenance, causing system downtime losses and increased operation and maintenance costs, while the water management parameter anomalies in Unknown State 2 are easy to be mistaken for membrane drying faults, and blind activation of humidification compensation measures will result in excessive membrane hydration and subsequent flooding faults, further deteriorating the stack performance; on the other hand, it will cause confusion in diagnostic thresholds, as the transient parameter fluctuations of unknown states blur the judgment threshold between “normal” and “fault”, making traditional threshold-based diagnostic methods unable to distinguish between “transient normal fluctuations” and “early fault anomalies”, thus leading to the two-way attenuation of diagnostic sensitivity and specificity; in addition, it will induce data distribution deviation, since the samples of unknown states will introduce “pseudo-abnormalities” in data distribution, and directly incorporating them into fault samples for training will lead to model overfitting, while incorporating them into normal samples will reduce the model’s ability to identify early faults, which exacerbates the diagnostic dilemma in small-sample scenarios.

Figure 2.

Data waveform comparison chart.

2.2.2. Data Pre-Processing

- (1)

- Data enhancement

The core objective of this study is to enhance the performance and generalization capability of machine learning models. To conclude, this study designs a Gaussian noise injection-based data augmentation scheme (a specific type of normal distribution noise) to expand the original dataset. Unlike conventional single-mode noise injection methods, the specific strategy adopted in this study is as follows: for each data file in the original dataset, multiple augmented samples are generated by adding Gaussian noise to the 20 sensor-measured features. Two noise levels are configured in this study, with standard deviations of 0.01 and 0.05, respectively—these intensities are determined based on the actual operating fluctuation range of PEMFC systems, so as to avoid excessive deviation from real operating conditions. It should be noted that the data augmentation via noise injection in this study only enhances data fluctuations and does not violate the physical operating constraints of PEMFC. Meanwhile, sequential labeling is applied to all augmented samples derived from the same original file; when splitting the dataset into training and test sets, all samples corresponding to the same original file are assigned to a single dataset (either the training set or the test set exclusively)-this prevents augmented data from appearing in both sets simultaneously, mitigates data information leakage, and ensures the independence of model training and validation. However, this scheme still has limitations when the volume of the original dataset is extremely small. This label-constrained augmentation strategy not only addresses the issue of insufficient small sample sizes but also ensures the validity of augmented data through physical constraint verification and leakage mitigation. It provides critical data support for model convergence in small-sample scenarios: each category of samples is expanded to 50 groups, which ensures sufficient feature representation for each operating state. For the number of expanded samples, refer to Table 2.

Table 2.

Statistics of the number of original and augmented data groups by category.

- (2)

- Data standardization

To ensure effective convergence and enhanced performance of the machine learning algorithms, it was imperative to standardize the dataset. The purpose of standardization is to convert the data distribution so that it conforms to a standard normal distribution, which has an average value of 0 and a standard deviation of 1. Below is the standardization formula:

where represents the original data point, is the mean of the data and is the standard deviation of the data.

3. Methodologies

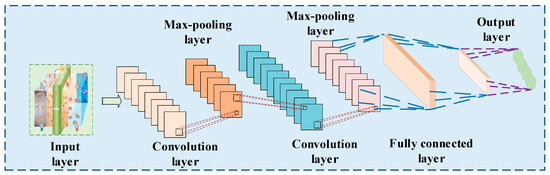

3.1. Convolutional Neural Network

Consider the case where the input data is a 3D tensor, designated as . In this scenario, the height and width of the input, represented by and , respectively, are known. Additionally, the number of channels, denoted by , is also a known quantity. The convolution kernel is defined by the size of the convolution kernel, , and the number of convolution kernels, , which is equal to the number of channels in the output feature map.

The output of the convolution operation can be calculated using the following equation:

where the coordinates of the output feature map, designated as , are related to the index of the convolution kernel, represented by the symbol .

Dropout is a regularization technique employed to prevent model overfitting. During the training phase, the dropout layer randomly discards a proportion of neurons, i.e., their output is set to zero, in order to reduce the co-adaptation between neurons, thereby enhancing the model’s capacity for generalization.

If input tensor is designated as , the output of the dropout layer can be calculated using the following equation:

where represents the probability of discarding.

Batch normalization (BN) is a technique employed to accelerate the training of deep neural networks. The technique accelerates convergence and improves the stability of the model by normalizing each small batch of data to have a mean of 0 and a variance of 1. Furthermore, it reduces the internal covariate shift (ICS) through linear transformations with learnable scaling and offset parameters.

Suppose input tensor is , where is the size of the small batch and is the feature dimension. The output of the batch normalization can be calculated by the following equation:

where and represent the mean and variance of the small batch of data, respectively. The learnable scaling and offset parameters, and , respectively, are also of interest. Finally, is a small constant that serves to prevent division by zero errors.

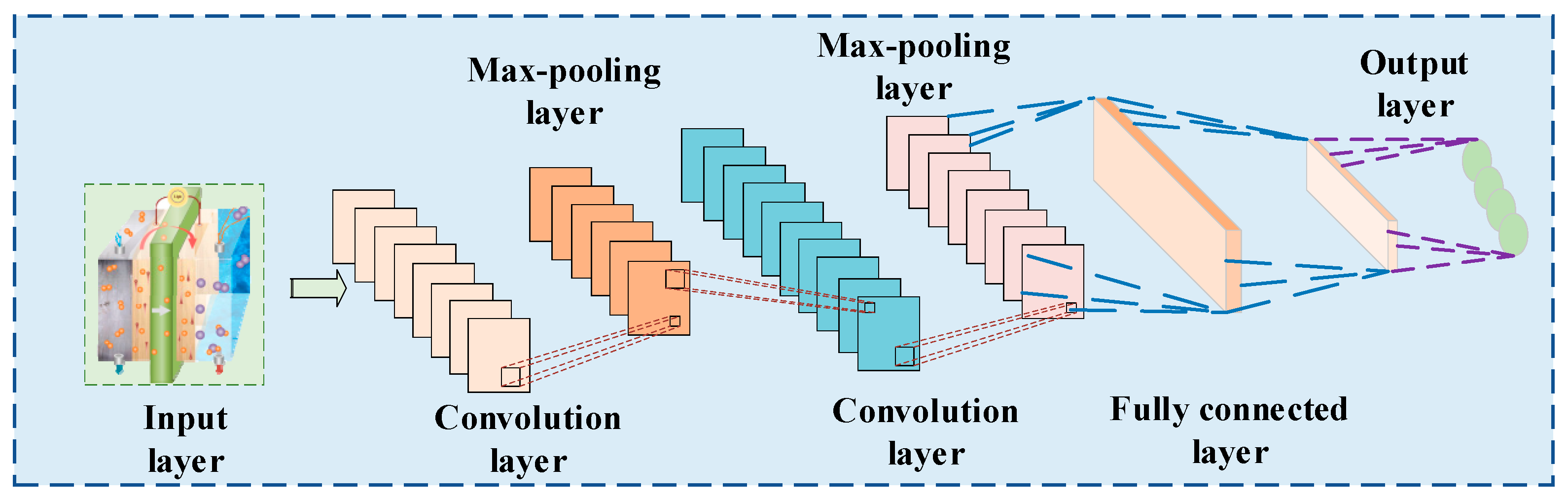

In the context of small-sample training, the combination of BN and Dropout exhibit significant advantages for model convergence: BN accelerates the convergence speed of deep networks by mitigating ICS, while Dropout reduces overfitting caused by limited sample diversity by randomly deactivating neurons. This dual regularization mechanism ensures that CNN module can learn robust local features even with constrained data volume, laying a solid foundation for subsequent spatiotemporal feature fusion. The architecture of the CNN is depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of CNN structure.

3.2. Bi-Directional Long Short-Term Memory Network

LSTM manages the information flow through the integration of a cell state along with three gating mechanisms, namely the input gate, forget gate, and output gate. This setup enables it to effectively capture long-term dependencies within sequential data. The cell state represents an information transfer line within LSTM, facilitating the transmission of information during sequence processing. Modification of this state is enabled by the gating mechanisms.

Let us suppose that at the time step t, the input is . The hidden state from the preceding time step is , and the cell state from the prior time step is .

Forget gate:

where is the weight matrix of the forgetting gate, is the bias term, and is the sigmoid activation function.

Input gate:

Input gate candidates:

New memory candidates:

Updates the unit status:

Output gate:

The activation value of the output gate:

The hidden state of the current timestep:

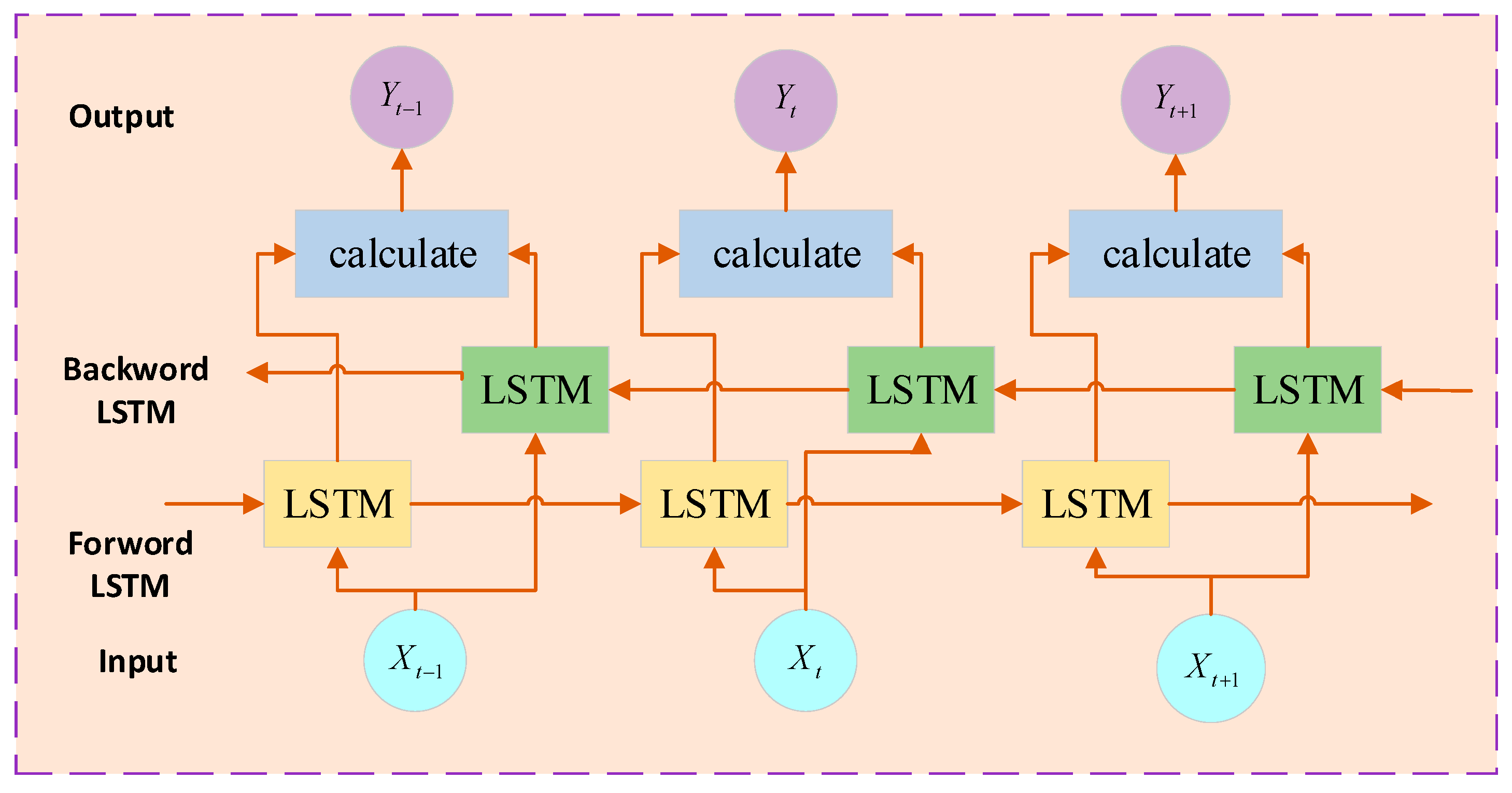

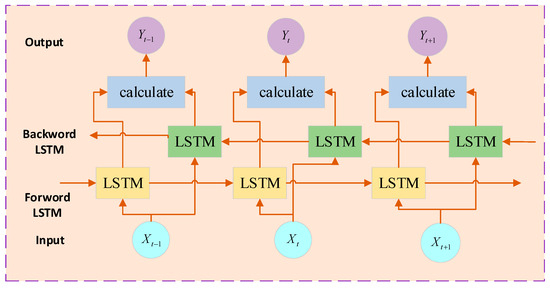

Bi-directional long short-term memory network (BiLSTM) consists of two separate LSTM layers. One-layer processes sequences in the forward manner, while the other processes them in the reverse way. The combination of the hidden states in both directions allows BiLSTM to utilize both future and past contextual information, thereby enhancing the modeling of sequences.

Suppose input sequence is .

While the forward LSTM can be expressed as

Meanwhile, the reverse LSTM can be expressed as

The combined hidden state yields

The term stacked LSTM is used to describe the process of combining multiple LSTM layers within a single model, with the output of each layer acting as the input for the subsequent layer. This methodology enhances the depth of the model and improves its capacity for expressing complex relationships. By incorporating multiple LSTM layers, the model can capture sequence features at varying levels, thereby enhancing the accuracy of sequence modeling. The architecture of BiLSTM is depicted in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of BiLSTM structure.

3.3. Waveform Fault Attention

To address the limitations of conventional attention mechanisms in capturing the spatiotemporal characteristics of PEMFC fault waveforms, this section proposes a WFA mechanism tailored for PEMFC fault diagnosis. The WFA integrates amplitude attention and time-difference attention to highlight fault-related salient features in both amplitude and temporal variation dimensions and further incorporates a multi-head attention module to enhance the model’s capability of modeling complex feature correlations. The overall framework of WFA is aligned with the implemented network structure, with each component’s calculation logic and mathematical expression clarified below [37].

Amplitude attention is designed to capture the salient amplitude features of PEMFC operation data waveforms, as abnormal amplitude fluctuations are often direct manifestations of faults. For an input sequence tensor:

where is batch size, is sequence length, and is feature dimension of each time step, the amplitude attention weight is calculated by first taking the absolute value of (to focus on amplitude magnitude regardless of direction) and then mapping it to a scalar attention score via a linear layer and sigmoid activation:

where denotes the feature tensor of the t-th time step in the input sequence; is the element-wise absolute value of , reflecting the amplitude of the t-th time step’s feature; and are the learnable weight matrix and bias term of the amplitude attention linear layer, respectively; is the amplitude attention weight of the t-th time step, with a larger value indicating a more critical amplitude feature for fault diagnosis.

Time-difference attention focuses on the temporal variation characteristics of PEMFC waveforms, as fault occurrences are usually accompanied by abrupt changes in parameter variation trends. First, the time-difference sequence of the input data is constructed by calculating the element-wise difference between adjacent time steps:

where is the time-difference tensor of the t-th time step. Then, the time-difference attention weight is calculated by mapping the absolute value of to a scalar score via a linear layer and sigmoid activation:

where is the element-wise absolute value of , reflecting the magnitude of the t-th time step’s temporal variation; and are the learnable weight matrix and bias term of the time-difference attention linear layer, respectively; is the time-difference attention weight of the t-th time step, with a larger value indicating a more significant temporal variation feature for fault identification.

The combined attention weight of WFA is obtained by element-wise multiplication of the amplitude attention weight and time-difference attention weight (denoted by ⊙ to eliminate the ambiguity of the original symbol). This multiplication operation ensures that only the time steps with both prominent amplitude features and significant temporal variations are assigned high weights, which effectively filters out irrelevant normal-state data and highlights fault-related spatiotemporal features:

where is the combined attention weight of the t-th time step.

Subsequently, the input sequence is weighted by in an element-wise manner to amplify the fault-related features and suppress noise and normal-state features:

where is the weighted feature tensor of the t-th time step, and the full weighted sequence is denoted as .

To further capture the multi-scale and cross-time-step correlations of the weighted fault features, a multi-head attention module is applied to the weighted sequence . The original ambiguity of the variable is corrected here: the query (), key (), and value () of the multi-head attention are all set to the weighted sequence (consistent with the implemented code logic), rather than an undefined . The multi-head attention operation splits the feature dimension into multiple parallel subspaces, computes attention scores in each subspace, and concatenates the results to obtain a comprehensive feature representation:

where is the final output of WFA mechanism, integrating the spatiotemporal fault features enhanced by amplitude-time difference attention and multi-scale correlation modeling. The number of attention heads is set adaptively to match the feature dimension and avoid dimension mismatch.

Compared with traditional spatiotemporal attention models and standard self-attention mechanisms, WFA mechanism possesses three core advantages in PEMFC fault diagnosis, enabling more accurate and efficient mining of fault features. First, the WFA adopts a targeted modeling paradigm for faulty waveform features. Unlike traditional self-attention that directly computes correlations across all time steps of raw time-series data, WFA first performs feature filtering via amplitude attention and time-difference attention, focusing solely on waveform segments with fault-related amplitude anomalies and temporal variation mutations, which effectively reduces noise interference and improves the efficiency of fault feature extraction. Second, WFA can realize intrinsic fusion of dual-dimensional spatiotemporal features. In contrast to existing spatiotemporal attention models that model spatial and temporal features separately, WFA deeply integrates amplitude features (reflecting the magnitude of single-time-step features) and time-difference features (reflecting variations between adjacent time steps) through element-wise multiplication of attention weights, thereby enhancing the distinguishability of similar faults. Third, the WFA achieves both lightweight deployment and interpretability. Its attention weights have clear physical meanings: amplitude attention corresponds to the severity of parameter deviation from the normal range, while time-difference attention corresponds to the abruptness of parameter changes.

3.4. Permutation Feature Importance

When it comes to fault diagnosis, it is extremely important to identify the contribution of each sensor to the model’s predictive effectiveness. This is especially pertinent when dealing with models that are trained utilizing data from 20 distinct sensors. Such models are computationally intensive, not only due to the sheer number of sensors but also owing to potential sensor redundancy. PFI is a model-independent feature importance assessment method that evaluates the importance of features by observing the extent to which model performance is degraded when the values of the features are randomly disrupted. The formula is presented as follows:

where is the performance of the model on the original data where the features are not disrupted, and is the number of times the features are repeatedly disrupted, which is used to minimize the effect of randomness.

Conventional feature selection methodologies are constrained by specific assumptions or performance metrics, frequently neglecting the effects of feature interactions. In contrast, model-independent PFI methodologies offer a more comprehensive approach. By permuting feature values, PFI evaluates their impact on model performance, thereby capturing interaction effects. In multi-sensor fault diagnosis, PFI has shown substantial benefits due to its model independence, global interpretability, and accounting for interaction effects, which collectively enhance the accuracy and reliability of feature selection.

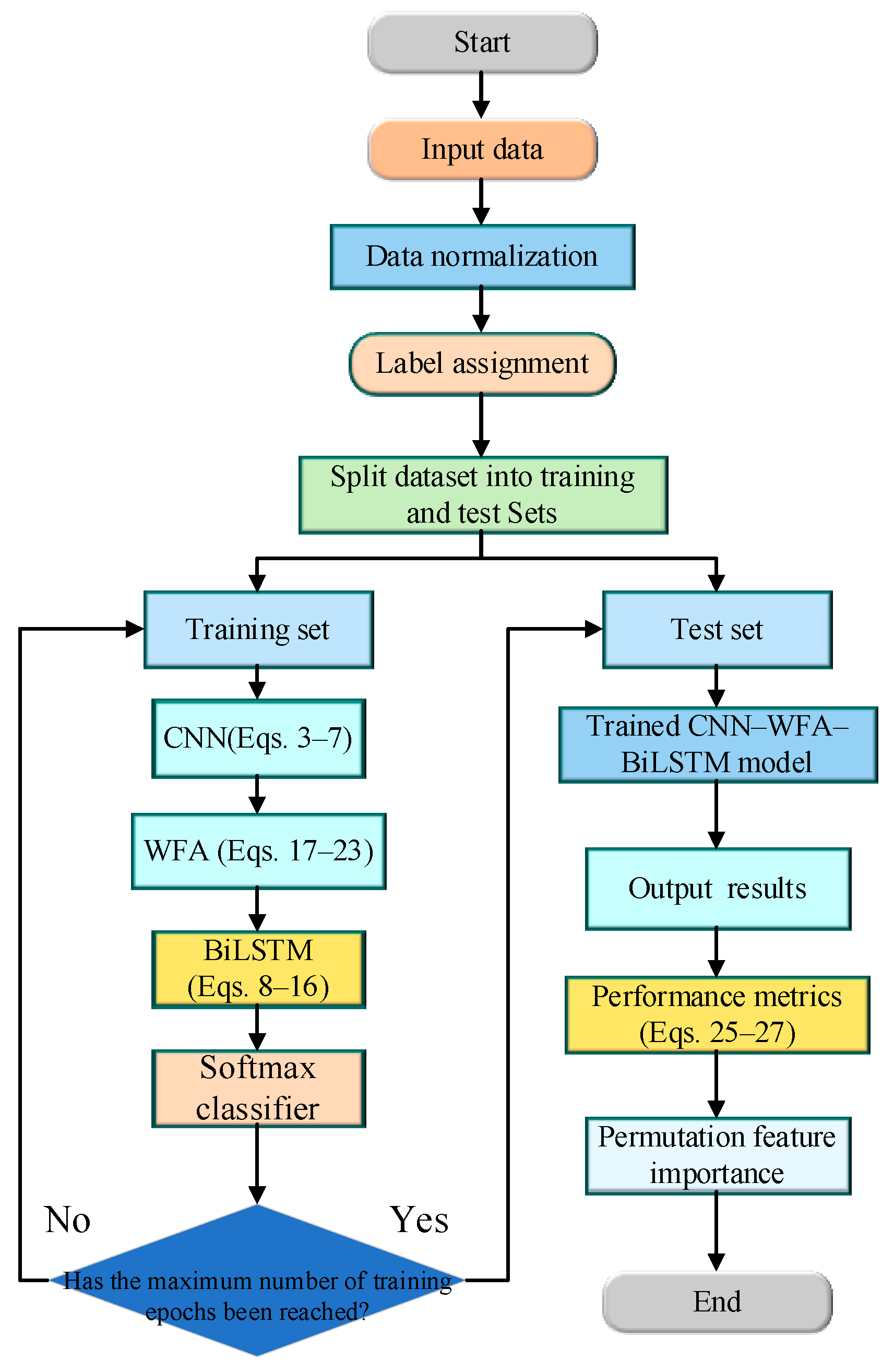

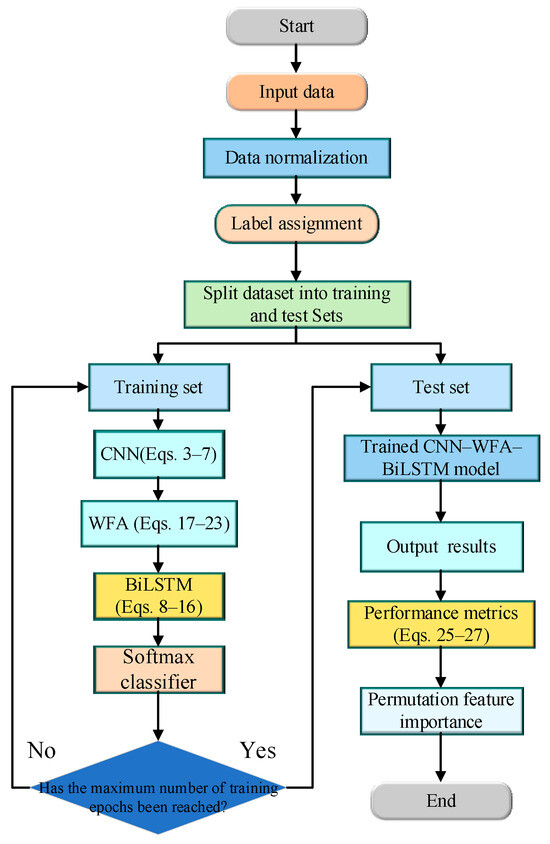

3.5. CNN-BiLSTM-WFA

This paper proposes a full-process data-driven fault diagnosis method for PEMFCs that integrates a CNN, a BiLSTM network, a WFA mechanism, and a PFI mechanism, with a focus on hierarchical feature extraction and optimization [38].

Firstly, raw monitoring signals (encompassing 20-dimensional sensor data of the PEMFC system, including parameters such as anode/cathode pressure, hydrogen/air flow rate, water inlet pressure/flow rate, and stack temperature) undergo standardization and data augmentation preprocessing to eliminate dimensional discrepancies and expand the volume of valid samples. The preprocessed data are fed into the CNN module for primary local feature extraction: this module employs 1D convolutional kernels and max-pooling layers to capture local spatiotemporal correlation features in both the time and frequency domains, such as adjacent time-step fluctuations of cathode inlet pressure, short-term mutations of primary water inlet flow rate, and local coupling patterns between stack temperature and anode reactant flow rate. In this stage, batch normalization and dropout regularization strategies are also introduced to suppress internal covariate shift and mitigate overfitting issues, ensuring that the extracted local features possess robustness and generalizability.

Subsequently, the local feature sequences extracted by CNN are input into BiLSTM model to establish bidirectional temporal dependencies. Unlike unidirectional sequence models, the dual-branch architecture of BiLSTM enables the capture of long-term dynamic temporal features of PEMFC faults while filtering out irrelevant temporal noise, thereby enhancing the model’s capability to identify fault evolution trends across the full-time window.

On the basis of the spatiotemporal features extracted by CNN-BiLSTM framework, this paper introduces WFA mechanism, which further highlights fault-related salient features through dual-attention and multi-head fusion design. Specifically, the amplitude attention module captures amplitude-abnormal features in a targeted manner by mapping the absolute values of feature tensors to attention weights; the temporal difference attention module focuses on temporal mutation features by calculating element-wise differences between adjacent time steps and assigning differentiated weights to mutation points. On this foundation, the multi-head attention module acts on the weighted feature sequences to realize the integration of multi-scale cross-time-step correlation features, amplifying the weights of key fault-related spatiotemporal features and suppressing redundant normal-state signals, thus improving the model’s diagnostic discriminability for highly similar states.

Finally, this paper adopts PFI method to analyze the model outputs and intermediate feature representations, quantifying and ranking the importance of each sensor-derived feature. By permuting the values of individual features and evaluating the degree of degradation in diagnostic performance, PFI method can identify core fault-sensitive features while filtering out low-contribution redundant features. This feature optimization step not only improves the interpretability of the diagnostic model by correlating data-driven features with physical fault mechanisms but also reduces computational costs and sensor redundancy by retaining only high-impact features, achieving a balance among diagnostic accuracy, reliability, and engineering applicability.

The hierarchical feature extraction design of CNN-BiLSTM-WFA framework is specifically optimized for small-sample scenarios: CNN module filters out irrelevant noise to extract discriminative local features, BiLSTM module captures long-term temporal dependencies to make up for the lack of feature completeness in small datasets, and WFA mechanism further highlights fault-related salient features. This targeted architecture significantly reduces the complexity of feature learning in the case of relatively few original samples, enabling the model to converge to a stable and high-precision state with limited training data.

Figure 5 illustrates the complete workflow of feature extraction, enhancement, optimization, and fault diagnosis.

Figure 5.

The flowchart of fault diagnosis.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Experiment Settings

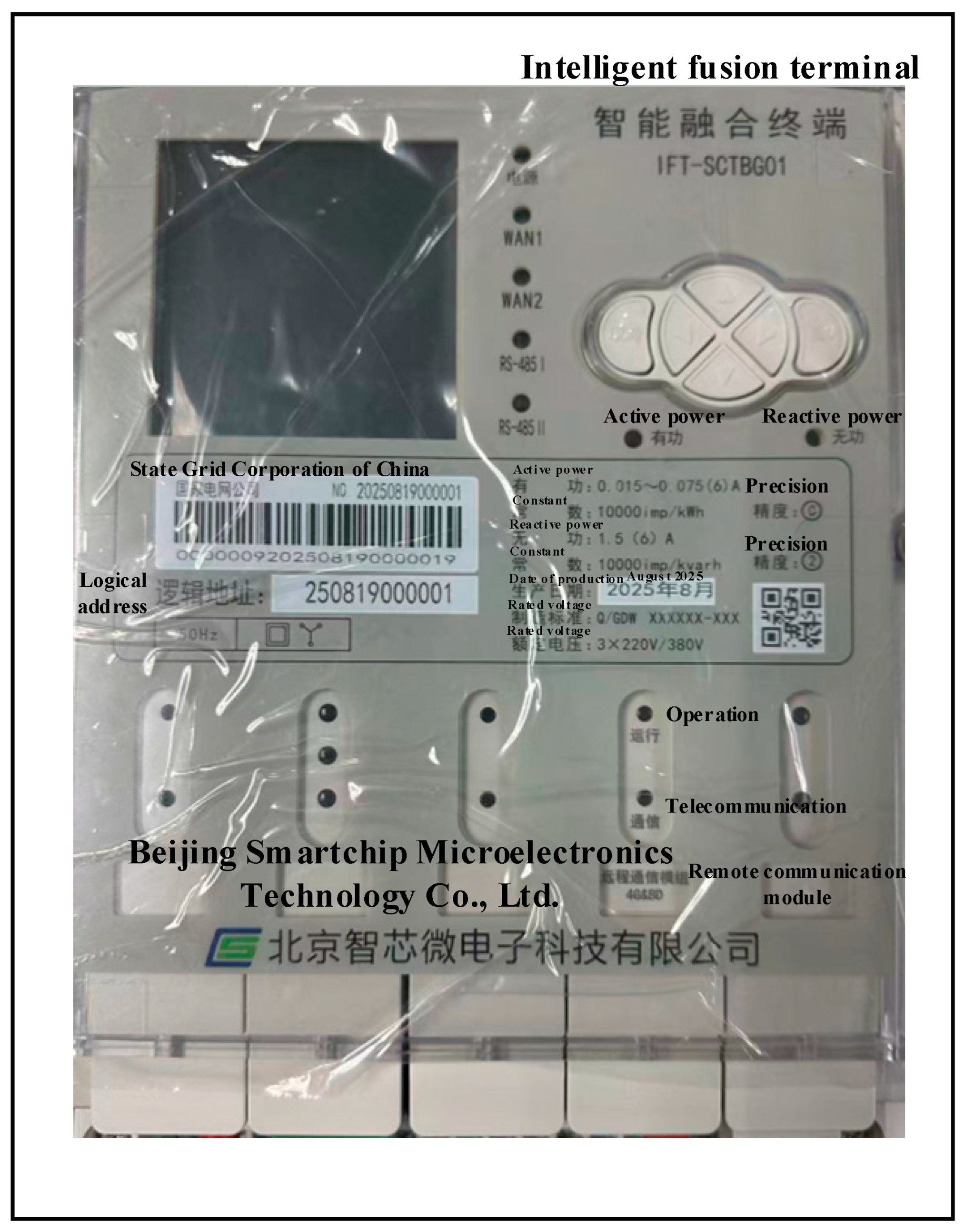

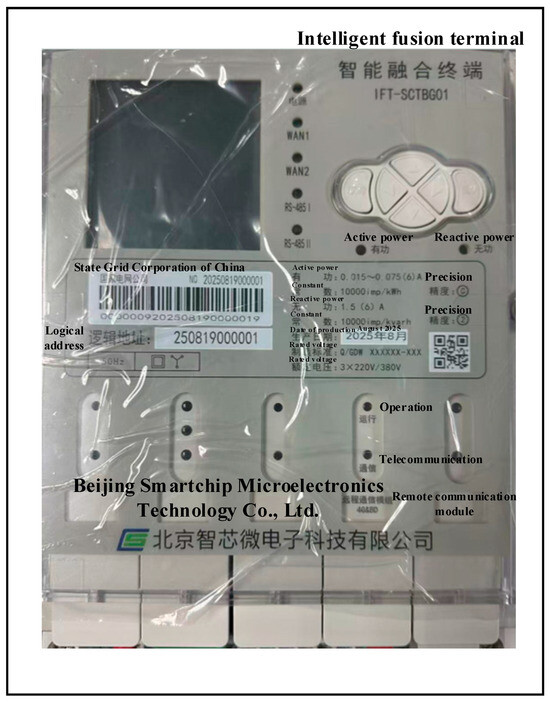

In this study, experiments were conducted on a server equipped with an Intel Core i5-14400 processor. The fault diagnosis method was developed using Python version 3.11 and PyCharm 2024 software. Meanwhile, data processing, algorithm integration, and result visualization were carried out through a smart terminal. The details of the smart terminal are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram of the smart terminal.

This intelligent terminal employs the SCA2004T as its main control chip, which features a 0.65/0.4 mm mixed-pitch FCCSP 636 package and integrates a suite of functional modules including the neural processing unit (NPU), reconfigurable control unit (RCU), High-performance image signal processor (ISP), video processing unit (VPU), and flexible video input/output interfaces. This integrated architecture not only provides comprehensive hardware support for the terminal but also endows it with both general video processing and artificial intelligence computing capabilities.

The terminal can not only meet the basic computing power requirement of ≥2 tops but also realize full-process efficient processing from data collection and artificial intelligence (AI) computing to result output by virtue of the SCA2004T’s hardware acceleration capability. Specifically, relying on the advanced noise reduction and HDR processing capabilities of ISP, the terminal can stably maintain a voltage and current data collection accuracy of ±0.1% at room temperature with a prediction time of less than 300 ms, which exceeds the basic requirement standards. Meanwhile, by integrating the video processing function of VPU, image enhancement function of ISP, and AI computing function of NPU, the terminal is capable of simultaneously processing sensor data and video stream data. It can fully satisfy the core requirements of high-precision data collection, fast AI inference, and stable industrial-grade operation, making it particularly suitable for real-time monitoring and predictive analysis in complex industrial environments. The specific parameters are detailed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Smart terminal parameters setting.

CNN-BiLSTM-WFA was employed for fault diagnosis, setting the learning rate ŋ to 0.001, the small batch size to 64, the epoch to 10, and the training set to 60%. Three commonly used metrics were chosen to quantify the diagnostic performance of the model: precision, recall, and F-score [39], to facilitate a comprehensive evaluation with the diagnostic results of CNN-BiLSTM-Multiplicative Attention, CNN [40], BiLSTM [41], LSTM [42] and bidirectional gated recurrent unit (BiGRU) [43]. The specific parameter settings of the six methods are shown in Table 4.

where , , and are true positive, false positive, and false negative, respectively.

Table 4.

Model parameters setting.

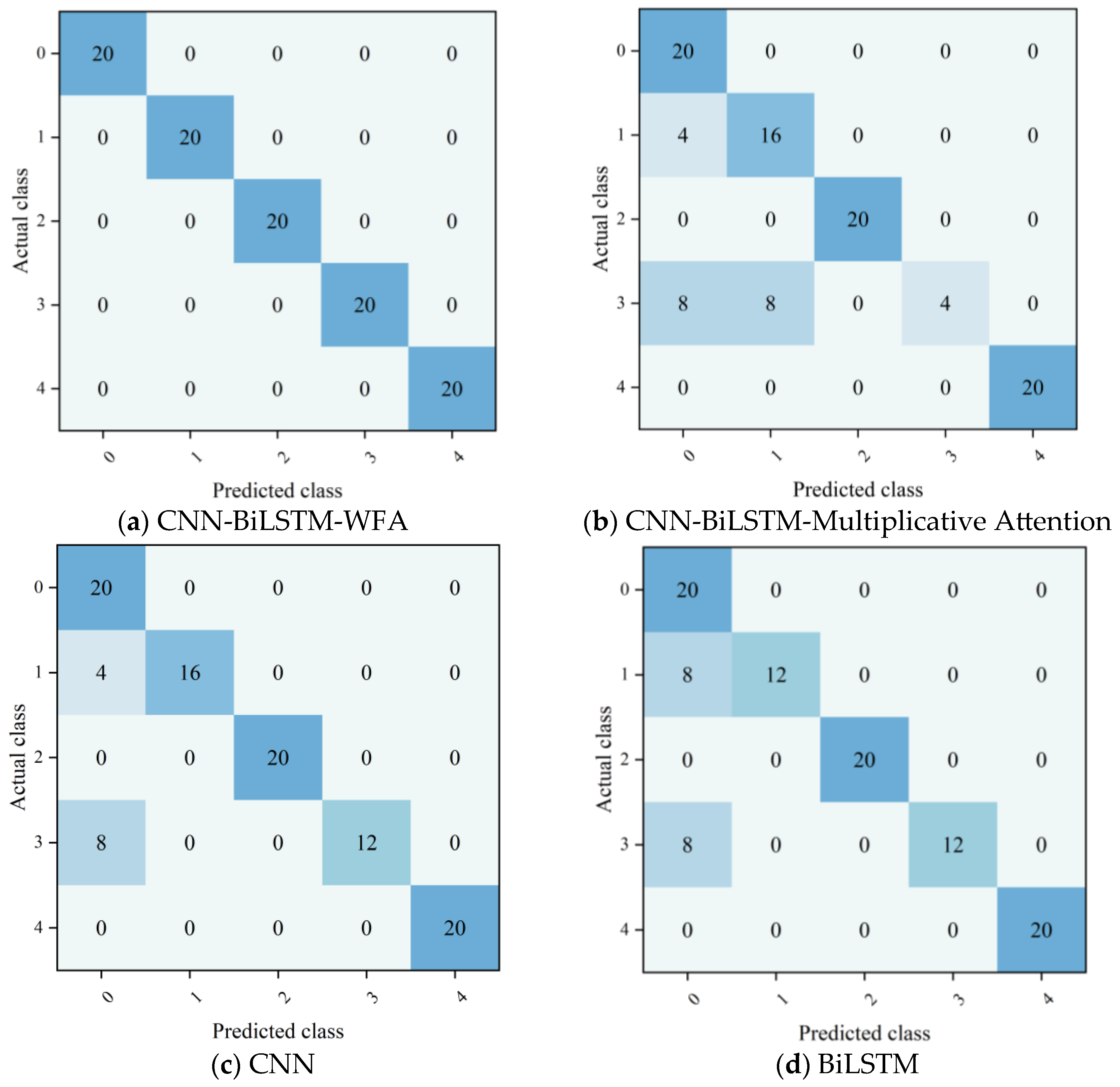

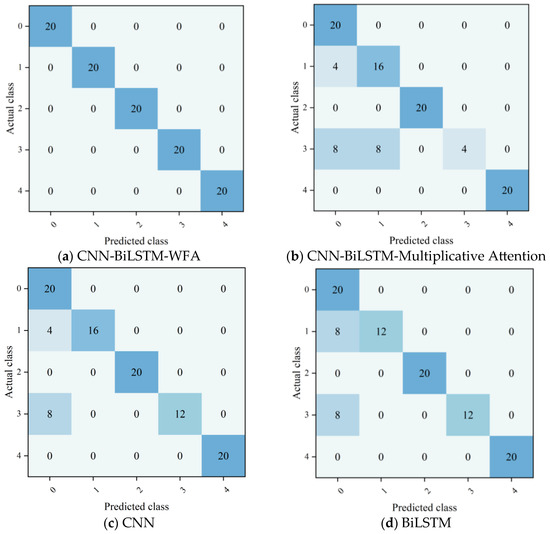

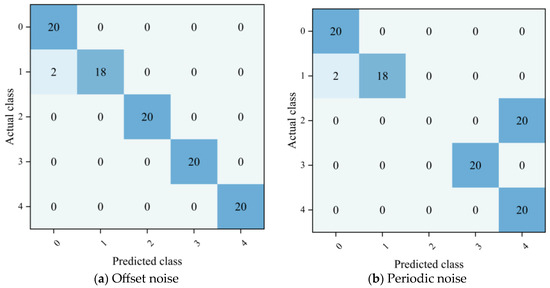

4.2. Comparison Experiments with Traditional Machine Learning Models

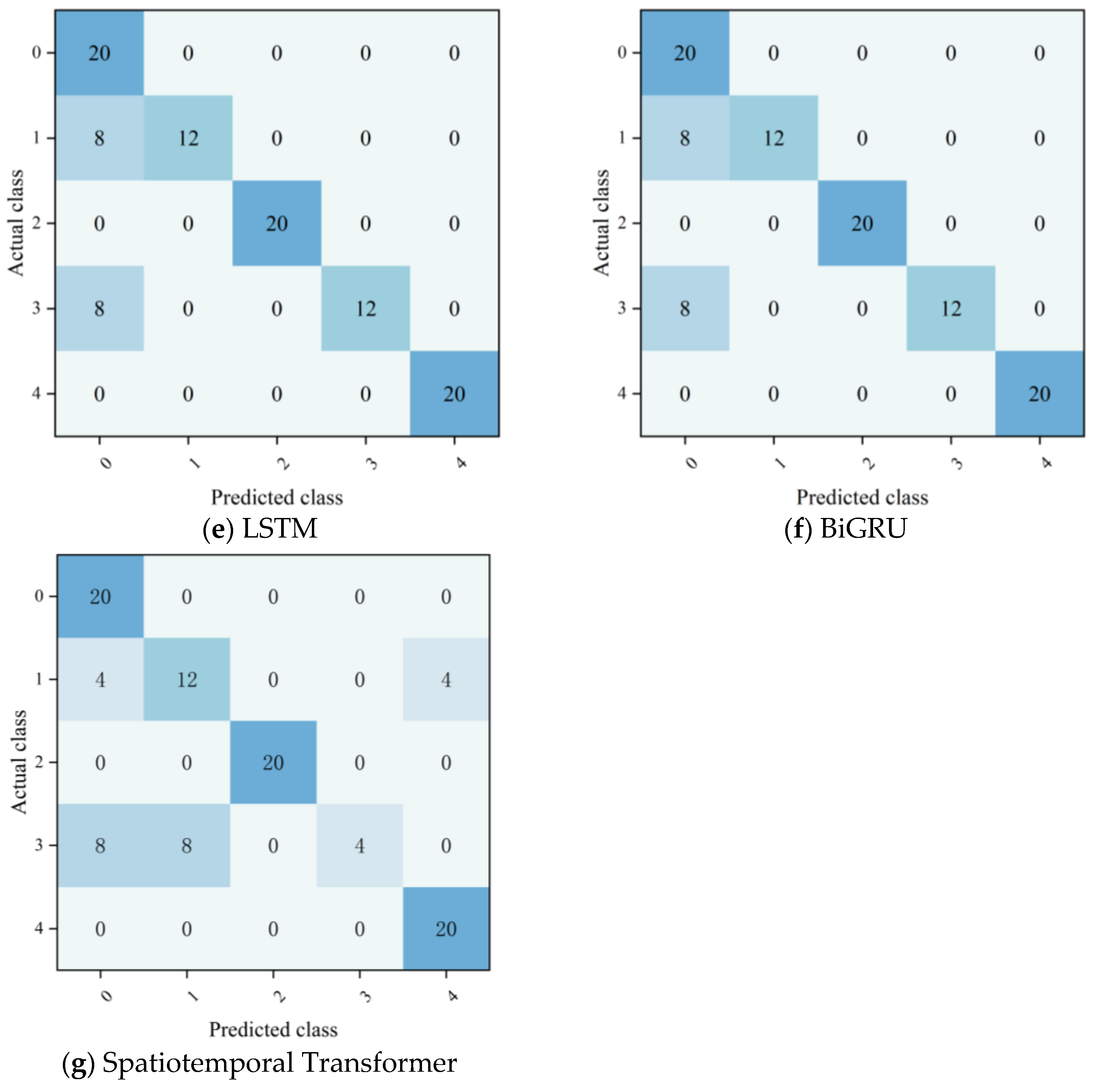

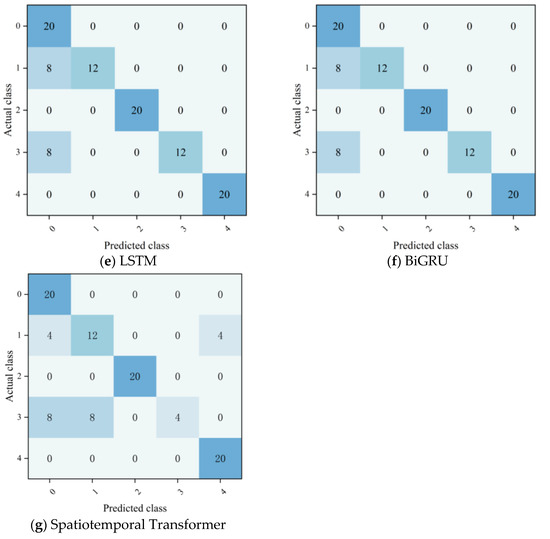

To comprehensively verify PEMFC fault diagnosis performance of the proposed CNN-BiLSTM-WFA model, this experiment selected five mainstream models, namely CNN-BiLSTM-Multiplicative Attention, CNN, BiLSTM, LSTM, and BiGRU, as the control group. With the confusion matrix serving as the core evaluation tool, diagnostic performance tests were conducted on five operational states of PEMFC. In the experiment, the labels of the five operational states were defined as follows: label 0 represents the normal operational state, label 1 denotes the hydrogen leakage fault, label 2 signifies the membrane drying fault, label 3 corresponds to unknown state 1, and label 4 stands for unknown state 2. The horizontal axis of the confusion matrix represents the fault type predicted by the model, while the vertical axis represents the actual fault type, and the element values in the matrix indicate the number of sample diagnoses under the corresponding states. The diagnostic results of various models are shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Confusion matrices of PEMFC fault diagnosis for different models.

It can be clearly seen from the confusion matrix results of PEMFC fault diagnosis for various models that the diagnostic performance of different models presents significant hierarchical characteristics under the five types of operating conditions. Among them, the CNN-BiLSTM-WFA model exhibits the optimal diagnostic performance, with the diagonal values of its confusion matrix all reaching the total number of samples under the corresponding operating conditions, achieving fully accurate identification of the five operating conditions without any misjudgments. The CNN-BiLSTM-Multiplicative Attention model can well diagnose the normal state and unknown state 2 but has obvious shortcomings in distinguishing between hydrogen leakage faults and unknown state 1. The four models (CNN, BiLSTM, LSTM, and BiGRU) show similar diagnostic performance; all of them can accurately identify membrane drying faults and unknown state 2 yet suffer from a large number of cross-misjudgments in the diagnosis of normal states, hydrogen leakage faults, and unknown state 1. The core reason for such differences in diagnostic performance lies in the high similarity of sensor monitoring waveforms between hydrogen leakage faults and unknown state 1, which makes it difficult for conventional models to capture the essential differences between them. In contrast, CNN-BiLSTM-WFA model achieves accurate distinction of such highly similar operating conditions by virtue of its unique attention mechanism.

To verify PEMFC fault diagnosis performance of the proposed CNN-BiLSTM-WFA model, five types of mainstream models were selected as controls in this experiment, and a comprehensive comparison was conducted from two dimensions: diagnostic accuracy and time efficiency, where time efficiency includes inference time and training time. The specific diagnostic results and time indicators of each model are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Fault diagnosis results of PEMFC under different methods.

In terms of diagnostic accuracy, CNN-BiLSTM-WFA model achieved 100% precision, recall, and F-score across all five operating states, realizing error-free diagnosis of all samples, and its overall diagnostic performance was far superior to that of the other five models. Compared with the CNN-BiLSTM-Multiplicative Attention model, the overall precision was improved by 0.14 and the overall F-score was increased by 0.23, indicating that in the field of fault diagnosis, WFA mechanism proposed in this paper is more capable of accurately diagnosing faults under highly similar operating conditions than the Multiplicative Attention mechanism. The four models (CNN, BiLSTM, LSTM, and BiGRU) exhibited highly homogeneous limitations in diagnostic performance, with many cross-misclassifications in the diagnosis of normal states, hydrogen leakage faults, and unknown state 1, and their overall precision, recall, and F-score all remained in the range of 0.84–0.88.

From the perspective of time efficiency indicators, due to the integration of the complex WFA mechanism, the CNN-BiLSTM-WFA model had a training time of 1164.4 s and an inference time of 11.4 s, both of which were the highest among the six models. In contrast, the CNN-BiLSTM-Multiplicative Attention model had a training time of 625.4 s and an inference time of 6.1 s; although its time consumption was significantly lower than that of the CNN-BiLSTM-WFA model, its diagnostic accuracy decreased sharply. The CNN model had the optimal time efficiency, with a training time of only 99.6 s and an inference time of 1.1 s, but its overall F-score was only 0.882. The results show that although the CNN-BiLSTM-WFA model sacrifices a certain degree of time efficiency, it achieves a breakthrough in PEMFC fault diagnosis performance with high diagnostic accuracy across all categories.

To verify the innovation of WFA mechanism, this study selects a representative spatiotemporal attention model, the Spatiotemporal Transformer, for quantitative comparison with the proposed CNN-BiLSTM-WFA model, with the results presented in Figure 7 and Table 5. In terms of computational efficiency, the training time and inference time of the Spatiotemporal Transformer are 1857.1 s and 14.0 s, respectively, whereas those of CNN-BiLSTM-WFA are 1164.4 s and 11.4 s, corresponding to a 37.3% reduction in training time and an 18.6% reduction in inference time. Regarding feature fusion performance, due to its global attention mechanism, the Spatiotemporal Transformer fails to effectively distinguish transient features between faulty and normal states, achieving a Precision of only 0.81 and an F-score of 0.72. In contrast, the CNN-BiLSTM-WFA achieves 100% diagnostic accuracy through the synergistic fusion of amplitude features and time-difference features. Result analysis confirms the innovation and superiority of the WFA mechanism: with lower computational costs, the mechanism achieves superior diagnostic precision, effectively addressing the challenge of synergistic fusion of spatiotemporal features faced by traditional spatiotemporal attention models, and providing efficient and accurate technical support for lithium-ion battery fault diagnosis.

The reason why this model achieves 100% diagnostic metrics across all categories is twofold. On the one hand, it benefits from its core WFA mechanism-this mechanism innovatively integrates amplitude of attention and temporal differences in attention. Specifically, amplitude attention can accurately capture key amplitude features such as waveform peaks and valleys, while temporal difference attention is capable of characterizing temporal dynamic variation laws by calculating signal differences between adjacent time steps. The synergistic effect of these two components enables the model to realize error-free identification of such highly similar states. In contrast, comparative models such as CNN, which lacks temporal correlation modeling capability, and BiLSTM, which is deficient in targeted focusing on key waveform features, both produce diagnostic misjudgments in the high-similarity signal interval. This not only verifies the actual diagnostic difficulty of unknown states but also highlights the technical superiority of the proposed model. On the other hand, it should be objectively noted that this perfect diagnostic performance is also limited by specific scenario settings. This study only focuses on diagnostic tasks for unknown states caused by single-type faults and normal transients, without involving complex working conditions of multi-fault coupling. Under multi-fault coupling scenarios, signal features exhibit multi-modal superposition characteristics, leading to a significant increase in diagnostic difficulty.

4.3. Model Stability Validation

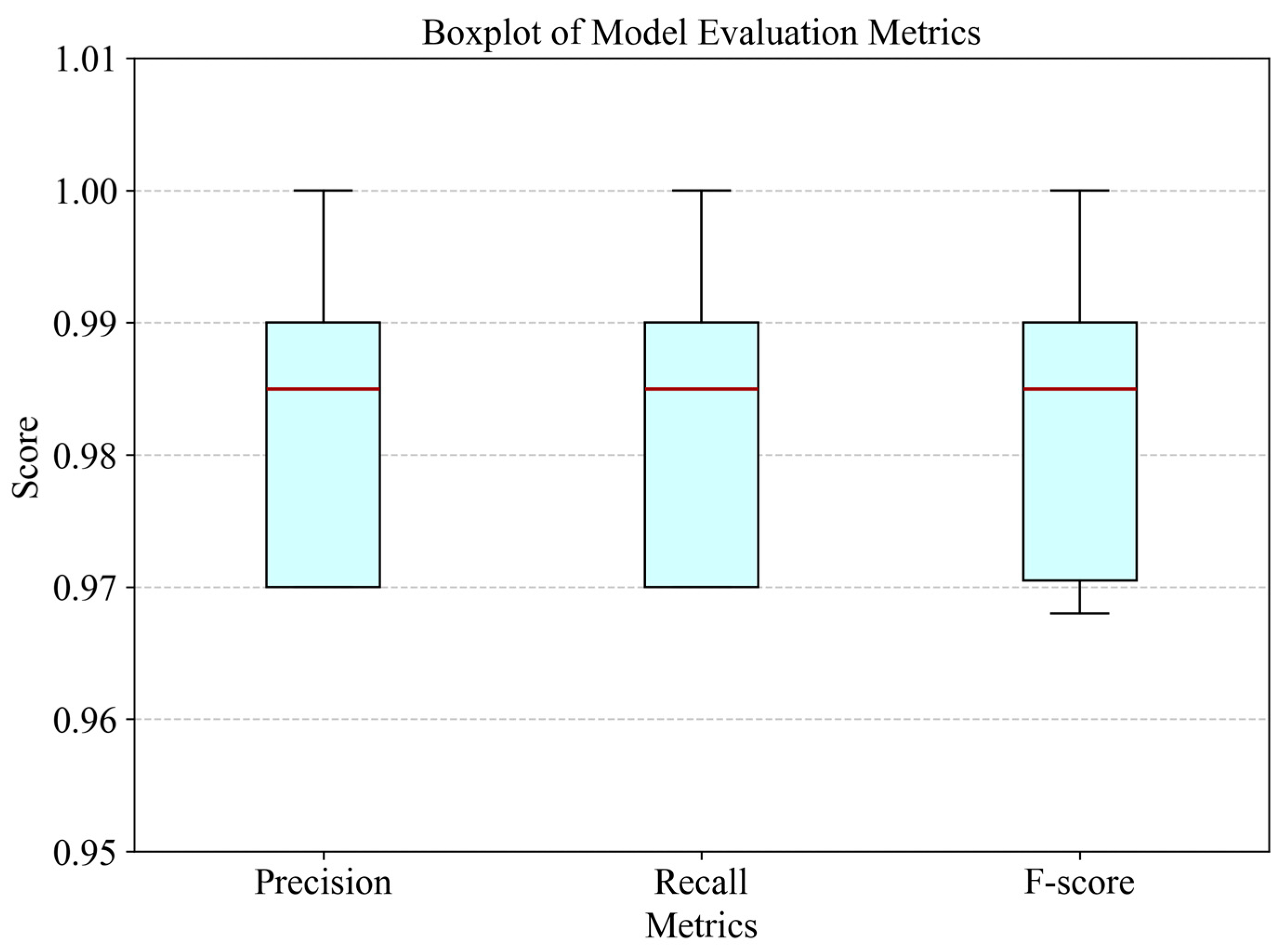

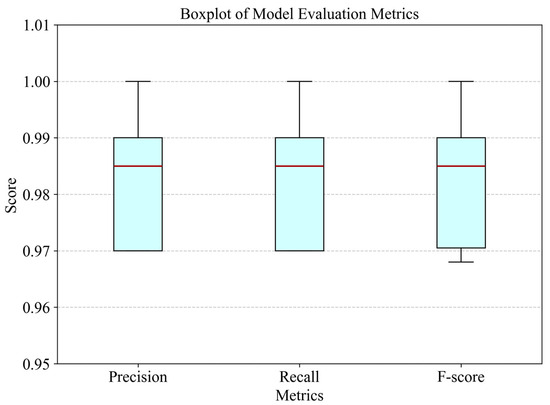

To verify the stability and robustness of the proposed CNN-BiLSTM-WFA model in PEMFC fault diagnosis task, 10 consecutive repeated experiments were conducted on the model in this study. The boxplot was adopted to visually analyze the core evaluation metrics (precision, recall, and F-score) of the experiments, and the experimental results are shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Boxplot of core diagnostic metrics for CNN-BiLSTM-WFA model stability verification.

From the distribution characteristics of the boxplot in Figure 8, the three core metrics of the model all exhibit the features of high centralization and low discreteness. The medians of the three metrics all reach above 0.98, the first quartiles are not less than 0.97, and the third quartiles are close to 1.00, indicating that the model maintains excellent and stable diagnostic performance throughout multiple repeated experiments without any performance collapse caused by sudden metric drops. Among the results of the 10 experiments, the diagnostic precision reached 97% in 4 experiments, 98% in 1 experiment, 99% in 3 experiments, and 100% (achieving full-sample accurate diagnosis) in another 2 experiments, with an overall average diagnostic precision of 98.3%. Notably, the stable performance of the model is particularly prominent in small-sample scenarios: even for the membrane drying fault and Unknown 1, the model still maintains consistent diagnostic precision across 10 repeated experiments. This indicates that the integrated strategies of data augmentation, regularization, and targeted feature extraction effectively address the convergence challenges of small-sample training, ensuring the model’s reliability in practical PEMFC fault diagnosis with limited data availability.

These results fully verify the stability and robustness of the model.

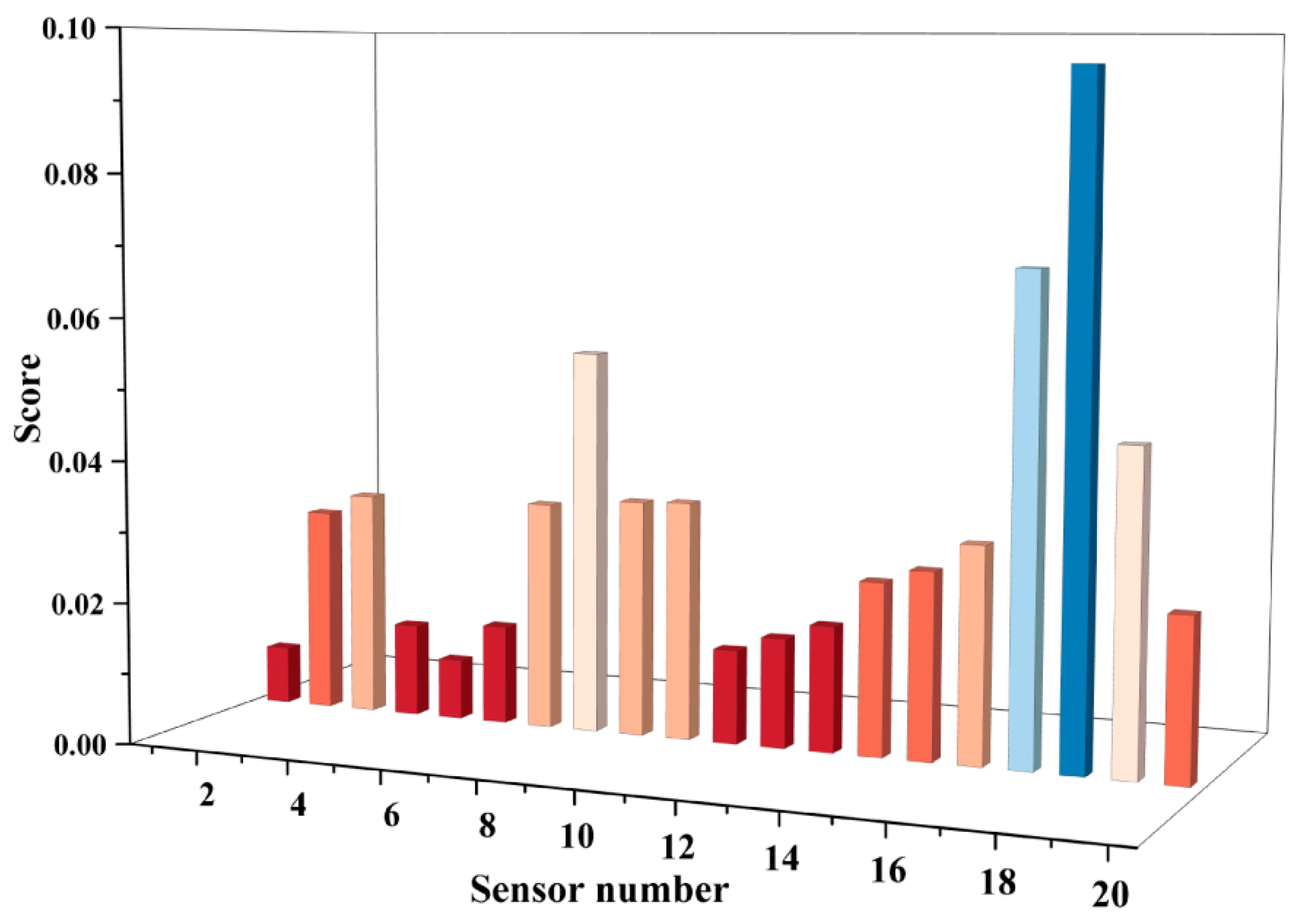

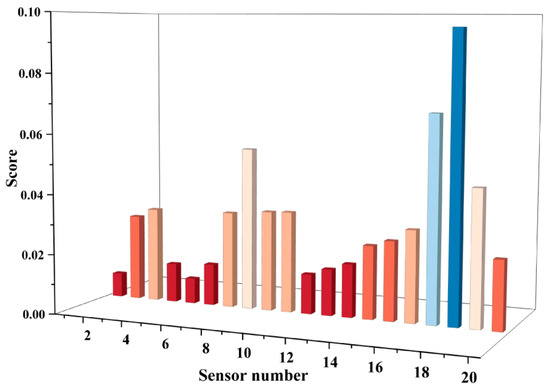

4.4. Illustration of Permutation Feature Importance Algorithm

In an effort to accurately assess the relative importance of each sensor in the system, a systematic analysis was conducted on 20 sensors using the PFI interpreter, with the results presented in Figure 9 (horizontal axis: sensor number; vertical axis: corresponding importance score). This visualization clearly stratifies the significance of different sensors; with sensor No. 18 (primary water inlet flow #2) assigned the highest importance rating and sensor No. 1 (anode outlet pressure #1) assigned the lowest. Specifically, the six sensors with the highest importance scores are ranked as follows: sensor 18 (primary water inlet flow #2), sensor 17 (primary water inlet pressure #1), sensor 8 (anode inlet pressure #2), sensor 19 (primary water inlet flow #1), sensor 1 (anode outlet pressure #1), and sensor 9 (cathode air inlet flow).

Figure 9.

PFI score for sensors.

The high importance of water inlet-related sensors (sensors 17, 18, 19, and their corresponding stack 2 counterparts such as sensor 16, primary water inlet pressure #2) can be directly linked to the physical fault mechanism of membrane drying elaborated in Section 2.1. As noted earlier, the hydration state of the proton exchange membrane is critical to maintaining proton conductivity and overall cell performance, and the primary water inlet flow and pressure are core parameters that determine the membrane’s water content. When membrane drying occurs, the rate of water removal from the membrane exceeds the rate of water supply, leading to abnormal fluctuations in water inlet flow and pressure. The PFI results confirm that these water management-related sensors are most sensitive to such faults, as their signals can directly reflect the membrane’s hydration status and thus enable early identification of drying faults.

For sensor 8 (anode inlet pressure #2), its high importance correlates with the hydrogen leakage fault mechanism. Hydrogen leakage (caused by seal failure, material defects, or operational errors) disrupts the stability of the anode’s hydrogen supply pressure, resulting in measurable deviations in anode inlet pressure. PFI interpreters identifies this sensor as a key indicator for hydrogen system anomalies, as pressure fluctuations at the anode inlet directly reflect the integrity of the hydrogen supply loop and the presence of leakage faults. In contrast, sensor 1 (anode outlet pressure #1) has the lowest importance because its signal shows minimal sensitivity to both membrane drying and hydrogen leakage-anode outlet pressure is less responsive to early-stage membrane hydration changes and only exhibits obvious deviations in severe, late-stage hydrogen leakage, making it an ineffective indicator for early fault diagnosis.

Compared to conventional feature extraction techniques, the PFI interpreter not only accurately identifies the sensors that are closely associated with the core fault diagnosis algorithms but also effectively eliminates sensor redundancy. This not only considerably reduces the cost of the monitoring system but also establishes a direct bridge between data-driven feature importance and the physical fault principles of PEMFC systems, providing a scientific foundation for both feature extraction and system optimization. The insights here integrate data analytics with domain knowledge, verifying that the most critical sensors from PFI results are precisely those that map to the primary failure modes of PEMFC.

4.5. Parameter Sensitivity Analysis

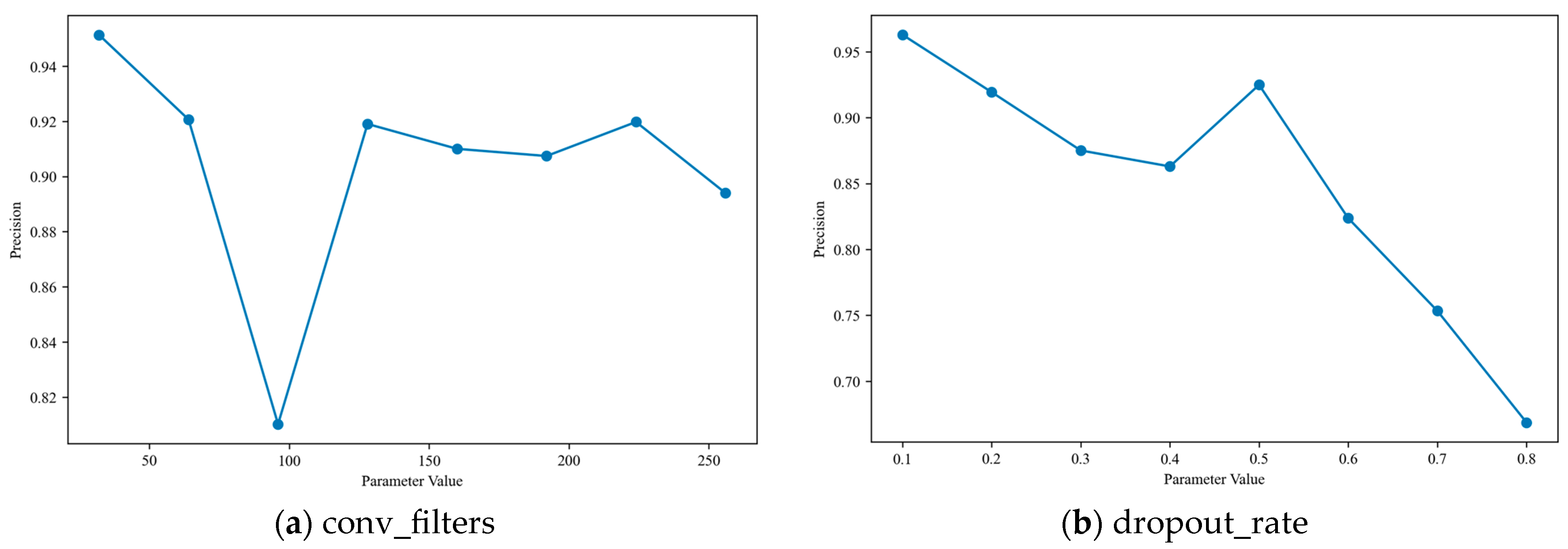

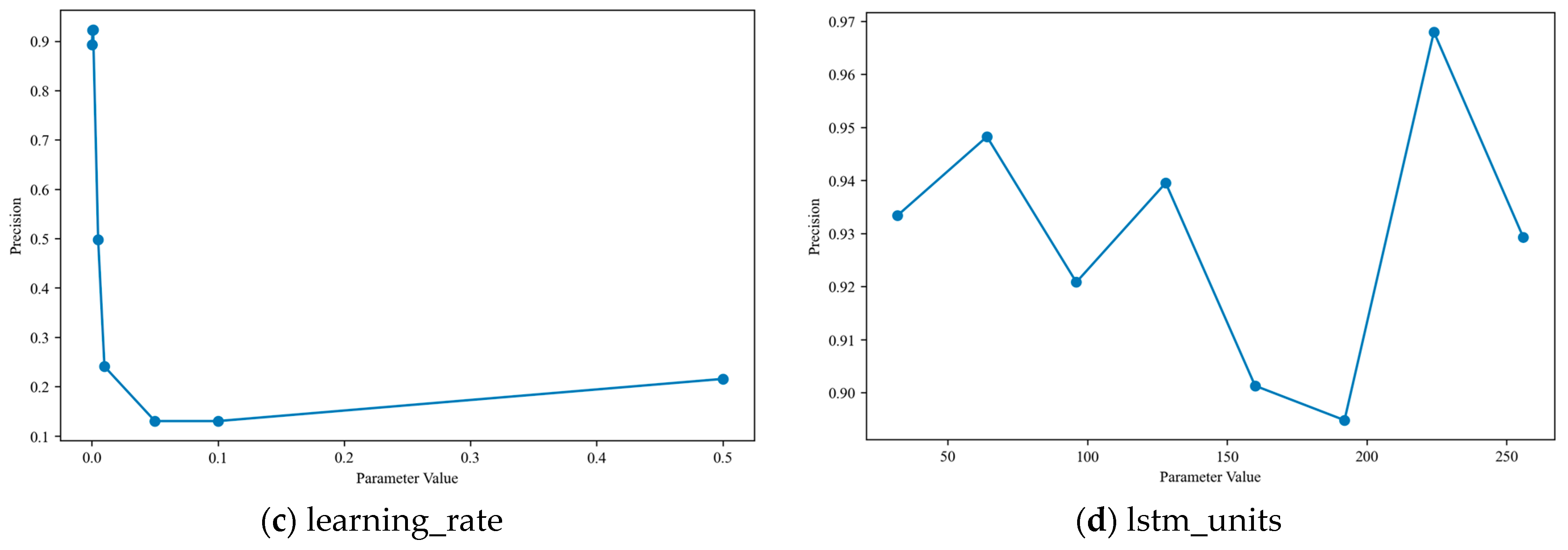

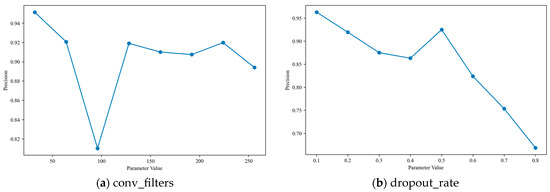

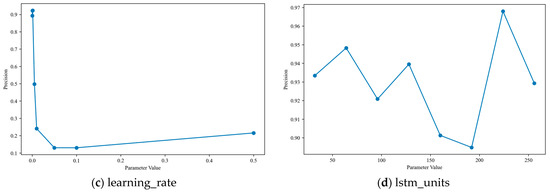

In the optimization of deep learning models, parameter sensitivity analysis plays a pivotal role, as it can quantitatively reveal the extent to which individual parameters affect model performance and thereby provide targeted guidance for hyperparameter tuning. For the CNN-BiLSTM-MHA hybrid model proposed in this study, four structurally critical and functionally irreplaceable hyperparameters—dropout_rate, conv_filters, learning_rate, and lstm_units—were selected for sensitivity analysis based on their distinct roles in the model’s architecture and training dynamics: dropout_rate was chosen due to its direct regulation of the model’s regularization intensity, which determines the level of random neuron inactivation during training and thus serves as a key safeguard against overfitting, a prevalent challenge for complex hybrid deep learning frameworks; conv_filters was identified as the core parameter of CNN module, which undertakes the extraction of local spatial features from input PEMFC monitoring data, with its quantity directly dictating the depth and richness of low-level feature capture for subsequent processing; learning_rate was prioritized as a fundamental optimizer hyperparameter that governs the step size of weight updates during backpropagation, thereby controlling the model’s ability to stably converge to a global optimal solution rather than oscillating or diverging during training; and lstm_units was included as the critical parameter of BiLSTM module, which dominates the model’s capacity to capture long-term temporal dependencies in sequential PEMFC operating data-a core functional requirement for achieving high-precision fault diagnosis. Based on this targeted parameter selection, a systematic sensitivity analysis was conducted, yielding the results presented in Figure 10, which demonstrate that the four hyperparameters exert significantly heterogeneous impacts on model performance: learning_rate exhibits high sensitivity, with values exceeding 0.005 leading to a marked decline in model precision due to the optimizer skipping the global optimal solution during weight updates; in contrast, conv_filters and lstm_units have minimal influence on performance, with variations in lstm_units causing a precision fluctuation of less than 0.1, a phenomenon that may be attributed to the MHA module’s more dominant role in high-level feature fusion and final fault classification; dropout_rate displays moderate sensitivity, where extreme values (either excessively high or low) induce underfitting or overfitting, respectively, and consequently result in a noticeable reduction in diagnostic precision.

Figure 10.

Sensitivity analysis of key parameters on CNN-BiLSTM-MHA model diagnostic precision.

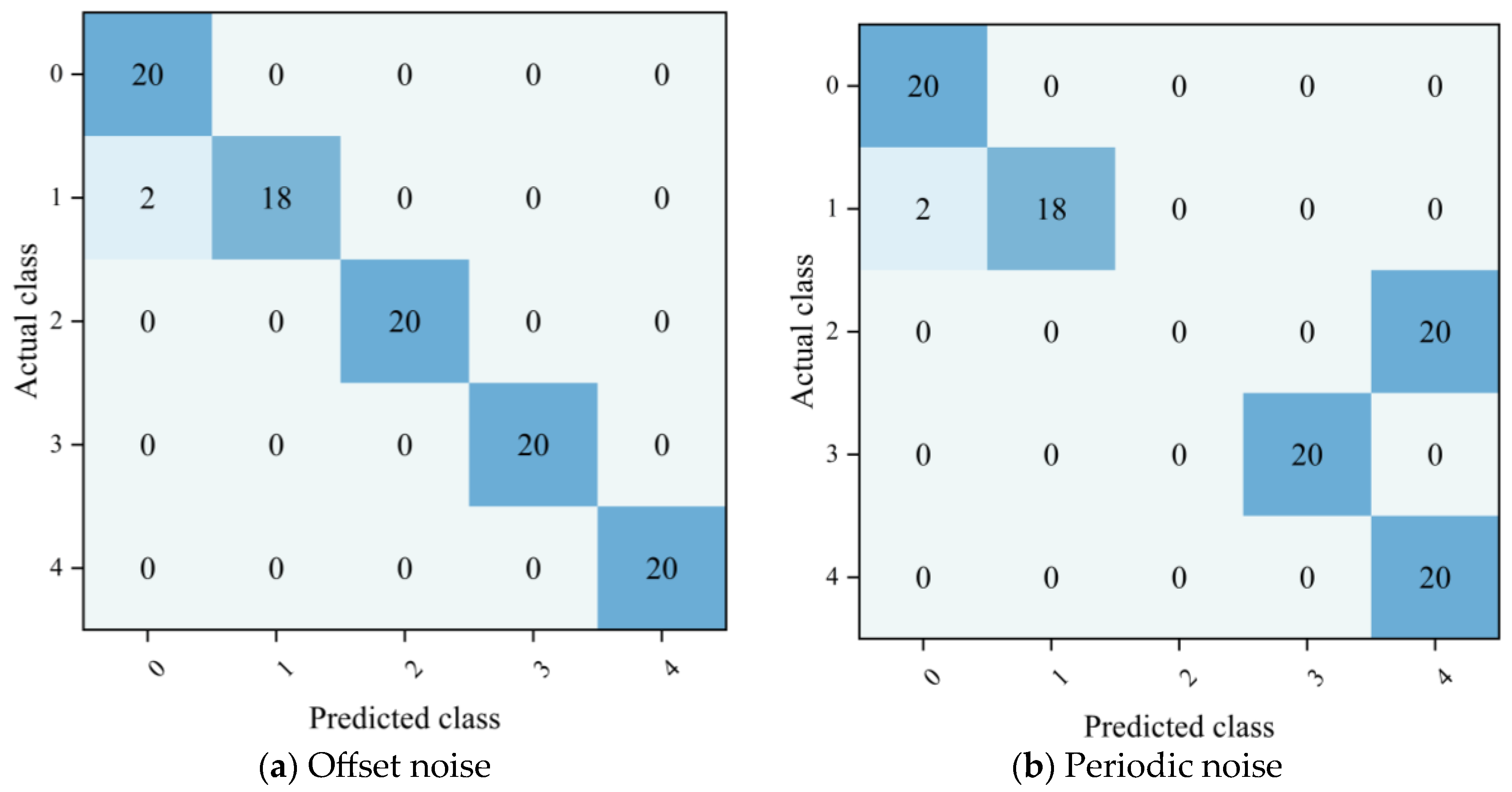

4.6. Sensitivity Analysis to Real-World Noises

To verify the robustness of the proposed CNN-BiLSTM-WFA model in practical industrial scenarios, this study designed three typical noise interference experiments, namely Gaussian noise, DC measurement offset noise with ±0.5% dynamic range, and power frequency/power ripple noise with 1–5% dynamic range. Among them, DC measurement offset noise was used to simulate the zero drift or measurement offset error of current/voltage sensors, which was implemented by adding a random constant offset of ±0.5% of the dynamic range of each column to the monitoring parameter columns; its amplitude was consistent with the basic measurement accuracy deviation of sensors, thus reflecting the inherent hardware errors of on-site sensors. In contrast, the power frequency/power ripple noise was employed to simulate the power frequency electromagnetic interference and power supply ripple in power systems, which was achieved by superimposing sinusoidal fluctuations with an amplitude of 1–5% of the dynamic range and a normalized frequency in the range of 0.05–0.15 on each parameter column; its periodic fluctuation characteristics were fully consistent with the grid interference scenarios when the PEMFC system was in grid-connected operation. The experimental results are shown in Figure 11 and Table 6.

Figure 11.

Confusion matrices of CNN-BiLSTM-WFA model for fault diagnosis under real-world noises.

Table 6.

Fault diagnosis results of PEMFC under different real-world noises.

In the Gaussian noise scenario, the model achieved a precision, recall, and F1-score of 1.00, and the corresponding confusion matrix showed a strict diagonal distribution, demonstrating complete robustness. Under DC offset noise, the overall precision of the model remained at 1.00, while the recall dropped to 0.98 and the F1-score decreased to 0.89; only 2 samples of label 1 were misclassified as label 0, and the other categories were identified accurately. Under the interference of power frequency ripple noise, the model performance degraded significantly, with the precision, recall, and F1-score dropping to 0.80, 0.78, and 0.79, respectively, and all 20 samples of label 2 were misclassified as label 4.

The experimental results indicate that the proposed model has strong robustness to Gaussian noise and sensor static offset noise, which can meet the diagnostic requirements of conventional industrial scenarios; however, it exhibits category-specific sensitivity to power frequency periodic dynamic noise in power systems, which needs further improvement and enhancement.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, a data-driven PEMFC fault diagnosis framework is proposed, encompassing data processing, temporal-spatial WFA construction, and interpretability analysis of fault diagnosis models. The veracity of this study was ascertained by employing genuine PEMFC experimental datasets. The principal research findings can be summarized as follows:

- (1)

- In this study, an innovative WFA mechanism is proposed. By integrating amplitude attention and temporal difference attention and then completing multi-scale cross-temporal feature fusion through a multi-head attention module, the mechanism effectively extracts fault features. Comparative experiments demonstrate that CNN-BiLSTM-WFA model equipped with WFA mechanism can achieve 100% diagnostic precision, recall, and F-score for five types of operating conditions. Compared with the traditional self-attention mechanism, the overall diagnostic precision is improved by 14%, providing an efficient feature extraction scheme for fault identification of PEMFC under complex operating conditions.

- (2)

- Stability analysis experiments show that the diagnostic precision of the CNN-BiLSTM-WFA model ranges from 97% to 100%, with an average diagnostic precision of 98.3%, which ensures the reliability of the model in practical engineering scenarios with limited data.

- (3)

- By quantifying the feature contribution of 20 monitoring sensors using PFI, this study identifies the core sensitive sensors for fault diagnosis. This not only effectively eliminates sensor redundancy and reduces the hardware cost of the monitoring system but also enhances the interpretability of the model.

- (4)

- A sensitivity analysis was conducted on the model, revealing the impacts of four major parameters on the model’s performance.

Although the diagnostic method proposed in this study has achieved favorable results, it still has limitations in the following four aspects.

- (1)

- The proposed model takes a long time for training and inference, and its computational efficiency has not yet met the core requirements of industrial application scenarios for real-time performance and low-cost deployment, making it difficult to directly adapt to the needs of online monitoring and rapid decision-making in engineering practice [44,45].

- (2)

- The scale of original data samples is relatively limited, and the issue of information leakage was not fully considered in the data augmentation process.

- (3)

- The acquisition of real-world scenario datasets is restricted, and cross-dataset verification has not been conducted, so the generalization ability and robustness of the model remain to be further verified.

- (4)

- This study has not incorporated experiments on small-sample scenarios, which to a certain extent limits the comprehensive evaluation of the model’s performance under data-scarce conditions.

In light of the limitations discerned during the diagnostic phase, future research endeavors are oriented towards addressing the ensuing four pivotal areas:

- (1)

- In response to the problem of low computational efficiency of the proposed model, future research will improve its efficiency through a combination of algorithm optimization and hardware adaptation, so as to meet the requirements of industrial applications.

- (2)

- To address the issues of limited sample size of raw data and information leakage, future research will expand high-quality data sources and establish a secure data augmentation mechanism, thereby constructing a reliable data system.

- (3)

- To enhance the generalization ability and robustness of the model, future research will build a multi-dimensional verification dataset, conduct cross-dataset and adversarial tests, and carry out targeted optimization of the model based on the test results.

- (4)

- Future research will focus on experiments under small-sample conditions. Specifically, we will conduct sensitivity analyses with different training proportions to evaluate the model’s performance across varying levels of data scarcity and carry out comparative studies with representative baseline methods of Few-shot Learning.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation, J.L.; writing—review and editing, W.X.; methodology, X.X.; software and formal analysis, Z.G.; resources, X.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Technology Project of State Grid Jiangsu Electric Power Co., Ltd. (J2025162).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Jian Liu, Wenqiang Xie, Xiaolong Xiao, Ziran Guo and Xiaoxing Lu were employed by the company State Grid Jiangsu Electric Power Co., Ltd. The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Nomenclature

| Abbreviations | false positive | ||

| AI | artificial intelligence | false negative | |

| BN | batch normalization | number of times the features | |

| BiLSTM | bi-directional long and short-term memory network | number of times the features are repeatedly disrupted | |

| BiGRU | bidirectional gated recurrent unit | probability of discarding | |

| BinE-CNN | binary matrix coded neural network | performance of the model on the original data | |

| CNN | convolutional neural network | true positive | |

| CNN-BiLSTM-WFA | convolutional neural network-bidirectional long short-term memory-waveform fault attention | sequence length | |

| ICS | internal covariate shift | weight matrix of the forgetting gate | |

| ISP | image signal processor | learnable weight matrix of the amplitude attention linear layer | |

| LSTM | long short-term memory | the learnable weight matrix of the time-difference attention linear layer | |

| MCNN | multiscale convolutional neural network | observed value of the i-th parameter in a faulty state | |

| MAPE | mean absolute percentage error | original data point | |

| NPU | neural processing unit | feature tensor of the t-th time step in the input sequence | |

| PEMFC | proton exchange membrane fuel cells | element-wise absolute value of | |

| PFI | permutation feature importance | difference between time steps t and t + 1 | |

| PHM | prognostics and health management | observed value of the i-th parameter in a normal steady state | |

| RCU | reconfigurable control unit | mean of the data | |

| RUL | remaining useful life | mean of the small batch of data | |

| VPU | video processing unit | standard deviation of the data | |

| WFA | waveform fault attention | sigmoid activation function | |

| 1DCNN | one-dimensional convolutional neural network | variance of the small batch of data | |

| Variables | difference between time steps t and t + 1 | ||

| final output of WFA mechanism | element-wise absolute value of | ||

| bias term | amplitude attention weight of the t-th time step | ||

| bias term of the amplitude attention linear layer | time-difference attention weight of the t-th time step | ||

| bias term of the time-difference attention linear layer | combined attention weight of the t-th time step | ||

| batch size | learnable scaling | ||

| feature dimension of each time step | offset parameters | ||

References

- Yang, B.; Zheng, R.Y.; Han, Y.M.; Huang, J.X.; Li, M.W.; Shu, H.C.; Su, S.; Guo, Z.X. Recent advances and summarization of fault diagnosis techniques for the photovoltaic system: A critical overview. Prot. Control Mod. Power Syst. 2024, 9, 36–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Guo, Z.X.; Wang, J.B.; Wang, J.T.; Zhu, T.J.; Shu, H.C.; Qiu, G.F.; Chen, J.; Zhang, J. Solid oxide fuel cell systems fault diagnosis: Critical summarization, classification, and perspectives. J. Energy Storage 2021, 34, 102153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Li, J.L.; Li, Y.L.; Guo, Z.X.; Zeng, K.D.; Shu, H.C.; Cao, P.L.; Ren, Y.X. A critical survey of PEMFC system control: Summaries, advances, and perspectives. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 9986–10020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.F.; Liu, H.; Yuan, Y.N.; Li, M.H. Can renewable energy development facilitate China’s sustainable energy transition? Perspective from Energy Trilemma. Energy 2024, 304, 132160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aba, M.M.; Sauer, I.L.; Amado, N.B. Comparative review of hydrogen and electricity as energy carriers for the energy transition. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 57, 660–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Wang, J.B.; Yu, L.; Shu, H.C.; Yu, T.; Zhang, X.S.; Yao, W.; Sun, L.M. A critical survey on proton exchange membrane fuel cell parameter estimation using meta-heuristic algorithms. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 265, 121660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminudin, M.A.; Kamarudin, S.K.; Lim, B.H.; Majilan, E.H.; Masdar, M.S.; Shaari, N. An overview: Current progress on hydrogen fuel cell vehicles. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 371–4388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandidayeni, M.; Macias, A.; Amamou, A.A.; Boulon, L.; Kelouwani, S.; Chaoui, H. Overview and benchmark analysis of fuel cell parameters estimation for energy management purposes. J. Power Sources 2018, 380, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasem, N.A.A. A recent overview of proton exchange membrane fuel cells: Fundamentals, applications, and advances. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 252, 123746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Li, D.Y.; Zeng, C.Y.; Chen, Y.J.; Guo, Z.X.; Wang, J.B.; Shu, H.C.; Yu, T.; Zhu, J.W. Parameter extraction of PEMFC via Bayesian regularization neural network based meta-heuristic algorithms. Energy 2021, 228, 120592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Liang, B.X.; Qian, Y.C.; Zheng, R.Y.; Su, S.; Guo, Z.X.; Jiang, L. Parameter identification of PEMFC via feedforward neural network-pelican optimization algorithm. Appl. Energy 2024, 361, 122857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.B.; Yang, B.; Zeng, C.Y.; Chen, Y.J.; Guo, Z.X.; Li, D.Y.; Ye, H.Y.; Shao, R.N.; Shu, H.C.; Yu, T. Recent advances and summarization of fault diagnosis techniques for proton exchange membrane fuel cell systems: A critical overview. J. Power Sources 2021, 500, 229932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.J.; Su, J.H.; Xie, B.; Shi, Y.; Huang, C.; Qu, X.L. Research on PEMFC fault diagnosis method based on fuzzy C means clustering and probabilistic neural network. Acta Energiae Solaris Sin. 2024, 45, 475–483. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, B.; Liu, X.W.; Zhang, L.Q.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, L.X.; Xie, C.J. Fault diagnosis of proton exchange membrane fuel cell integrated system based on google net and transfer learning. Proc. CSEE 2024, 44, 5147–5157. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Meng, M.; Liu, M.J.; Mei, J.; Li, X.; Grigoriev, S.; Hasanien, H.M.; Tang, X.W.; Li, R.; Sun, C.Y. Polarization loss decomposition-based online health state estimation for proton exchange membrane fuel cells. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 157, 150162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Sun, C.Y.; Mei, J.; Tang, X.W.; Hasanien, H.M.; Jiang, J.H.; Fan, F.L.; Song, K. Fuel cell life prediction considering the recovery phenomenon of reversible voltage loss. J. Power Sources 2025, 625, 235634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.Y.; Sun, Y.N.; Tang, X.W.; Mao, L. Enabling unsupervised fault diagnosis of proton exchange membrane fuel cell stack: Knowledge transfer from single-cell to stack. Appl. Energy 2024, 360, 1228144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrone, R.; Zheng, Z.; Hissel, D.; Pera, M.C.; Pianese, C.; Sorrentino, M.; Becherif, M.; Yousfi-Steiner, N. A review on model-based diagnosis methodologies for PEMFCs. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2013, 38, 7077–7091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Petrone, R.; Pera, M.C.; Hissel, D.; Becherif, M.; Pianese, C.; Steiner, N.Y.; Sorrentino, M. A review on non-model based diagnosis methodologies for PEM fuel cell stacks and systems. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2013, 38, 8914–8926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, B.; Zhang, Z.H.; Cheng, J.S.; Huo, W.W.; Zhong, Z.X.; Wang, M.R. Data-driven flooding fault diagnosis method for proton-exchange membrane fuel cells using deep learning technologies. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 251, 115004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Kim, J.; Choi, H.; Kwon, O.; Jang, Y.; Ryu, S.; Lee, H.; Shim, K.; Park, T.; Cha, S.W. Pre-diagnosis of flooding and drying in proton exchange membrane fuel cells by bagging ensemble deep learning models using long short-term memory and convolutional neural networks. Energy 2023, 266, 126441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.Y.; Mao, L.; Hu, Z.Y.; Huang, W.G.; Wu, Q.; Jackson, L. A novel densely connected neural network for proton exchange membrane fuel cell fault diagnosis. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 40041–40053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Hou, Z.J.; Cai, J. Data-based flooding fault diagnosis of proton exchange membrane fuel cell systems using LSTM networks. Energy AI 2021, 4, 100056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laribi, S.; Mammar, K.; Sahli, Y.; Koussa, K. Analysis and diagnosis of PEM fuel cell failure modes (flooding & drying) across the physical parameters of electrochemical impedance model: Using neural networks method. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2019, 34, 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.H.; Zhang, B.X.; Zhu, K.Q.; Zheng, X.Y.; Zhang, C.L.; Chen, Z.L.; Yang, Y.R.; Huang, T.M.; Bo, Z.; Wan, Z.M.; et al. Fault diagnosis of PEMFC based on fatal and recoverable failures using multi-scale convolutional neural networks. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 80, 916–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, F.; Chen, T.; Zhang, J.W.; Zhang, S.J. Water management fault diagnosis for proton exchange membrane fuel cells based on deep learning methods. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 28163–28173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Lu, Y.D.; Bao, D.T.; Wang, K.Y.; Shan, J.; Hou, Z.J. Real-time data-driven fault diagnosis of proton exchange membrane fuel cell system based on binary encoding convolutional neural network. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 10976–10989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.Y.; Ran, H.J.; Chen, Z.Y.; Kwan, T.H.; Yao, Q.H. Online pre-diagnosis of multiple faults in proton exchange membrane fuel cells by convolutional neural network based bi-directional long short-term memory parallel model with attention mechanism. Energies 2025, 18, 2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Yang, B.; Zheng, R.Y.; Hou, Y.T.; Li, H.B.; Gao, D.K.; Guo, Z.X.; Jiang, L. Fault diagnosis of proton exchange membrane fuel cell using multiple convolutional neural networks with multi-scale attention mechanism. Inf. Sci. 2025, 720, 122524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, T.J.; Guo, Z.L.; Fang, T. Proton exchange membrane fuel cell fault diagnosis based on operation data temporal and spatial characteristics and stacking ensemble learning. Proc. CSEE 2023, 43, 5461–5470. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.Y.; Sun, Y.N.; Mao, L.; Zhang, H.; Jackson, L.; Wu, Q.; Lu, S.X. Efficient fault diagnosis of proton exchange membrane fuel cell using external magnetic field measurement. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 266, 115809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.W.; Li, Q.; Chen, W.R.; Jiang, L.; Yu, J.J. Research on PEMFC water management fault diagnosis method based on probabilistic neural network and linear discriminant analysis. Proc. CSEE 2019, 39, 3614–3622. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.H.; Gao, Y.; Yu, J.; Tian, L.; Yin, C. Data-driven fault diagnosis of PEMFC water management with segmented cell and deep learning technologies. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 67, 715–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.H.; Li, G.L.; Xie, M.L.; Xu, Q.M.; Zhang, G. A probabilistic analysis method based on Noisy-OR gate Bayesian network for hydrogen leakage of proton exchange membrane fuel cell. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2024, 243, 109862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Yang, M.Y.; Sun, C.Y.; Xu, S.C. Liquid water characteristics in the compressed gradient porosity gas diffusion layer of proton exchange membrane fuel cells using the lattice Boltzmann method. Energies 2023, 16, 6010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, L.; Jackson, L.; Dunnett, S. Fault diagnosis of practical polymer electrolyte membrane (PEM) fuel cell system with data-driven approaches. Fuel Cells 2017, 17, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.X.; Li, L.W.; Chen, J.; Wang, D.Q. A multi-head attention mechanism aided hybrid network for identifying batteries’ state of charge. Energy 2024, 286, 129504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, J.; Meng, X.; Tang, X.W.; Li, H.R.; Hasanien, H.; Alharbi, M.; Dong, Z.; Shen, J.B.; Sun, C.Y.; Fan, F.L.; et al. An accurate parameter estimation method of the voltage model for proton exchange membrane fuel cells. Energies 2024, 17, 2917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.J.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, L.Y.; Deng, H.Z.; Cao, J.; Bai, J. A novel dynamic radius support vector data description based fault diagnosis method for proton exchange membrane fuel cell systems. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 35825–35837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Hu, L.; Song, T.T. Health state estimation of lithium-ion batteries based on CNN-Bi-LSTM. Shandong Electr. Power 2023, 50, 66–72. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, F.; Liu, S.H.; Wang, T.H.; Liu, R. Optimal planning for integrated electricity and heat systems using CNN-BiLSTM-Attention network forecasts. Energy 2024, 309, 133042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.S.; Liu, J.W.; Jia, S.Y.; Weng, J. Research on wind turbine status monitoring methods based on improved PSO-LSTM algorithm. Shandong Electr. Power 2024, 51, 30–37. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Niu, D.X.; Yu, M.; Sun, L.J.; Gao, T.; Wang, K.K. Short-term multi-energy load forecasting for integrated energy systems based on CNN-BiGRU optimized by attention mechanism. Appl. Energy 2022, 313, 118801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.F.; Yu, Z.L.; Sun, G.H.; Liu, J.X. Deep learning-based fault diagnosis and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy frequency selection method for proton exchange membrane fuel cell. J. Power Sources 2024, 591, 233815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]