Experimental Study on Electrolytic Simulation of Production Capacity Interference in Asymmetric Fishbone Wells

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experiment Methods

2.1. Experimental Principle

2.2. Experimental Apparatus

2.3. Experimental Steps

- (1)

- Experimental model making. The model material was 1 mm diameter thin copper wire to make fishbone well models.

- (2)

- Supply boundary and CuSO4 electrolyte solution preparation. The material of supply boundary was purple copper strip, sized according to the actual specifications of water tank; Configure corresponding CuSO4 solutions according to the required electric conductivity in the experiment.

- (3)

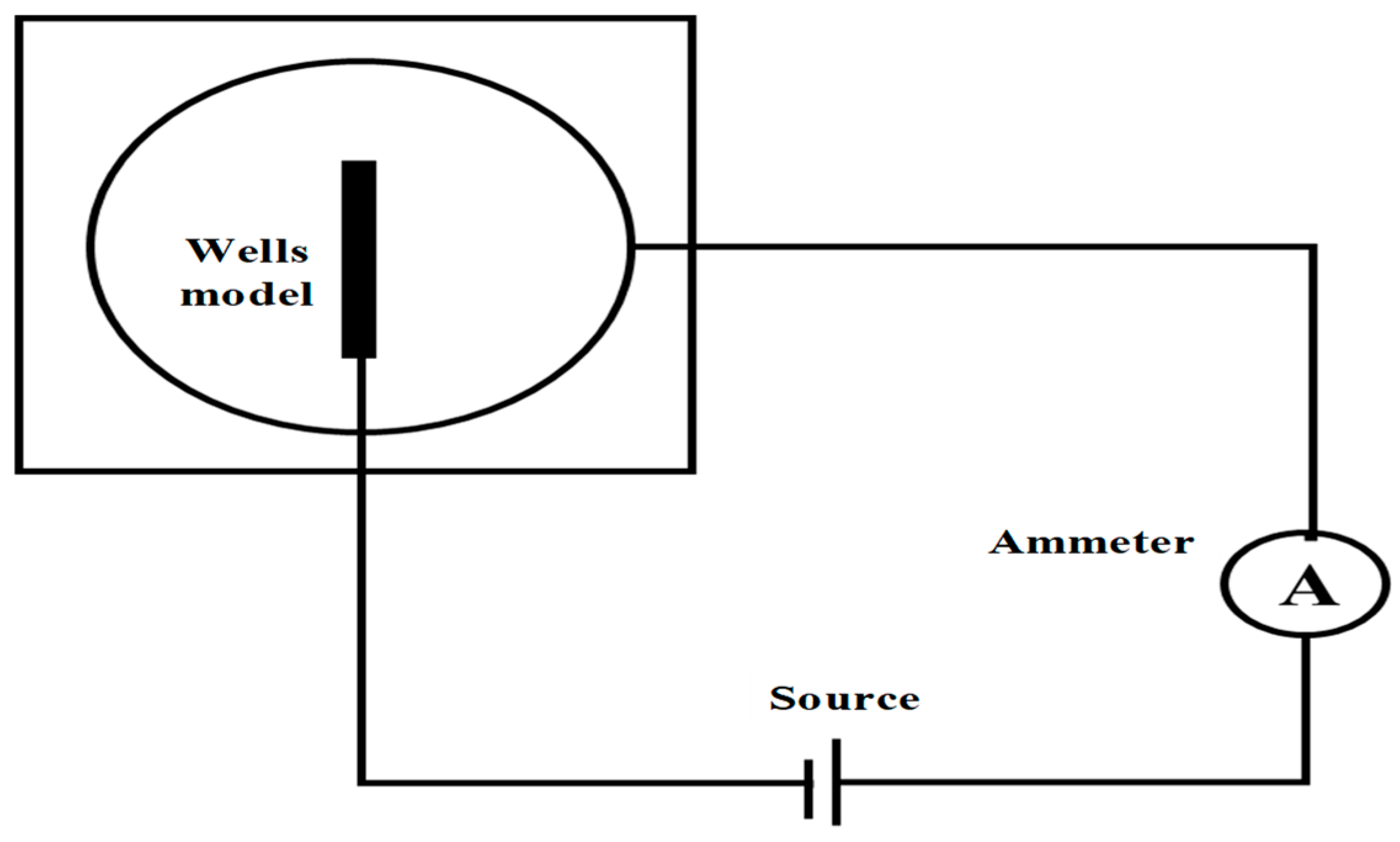

- Connect the circuit according to the circuit diagram shown in Figure 2, turn on the circuit and measure the total current through the well.

- (4)

- Connect the circuit according to the circuit diagram shown in Figure 3, turn on the circuit and measure voltage.

- (5)

- Data acquisition. Set relevant parameters such as test pitch and test distance of mechanical arm controller program according to relevant requirements such as number and position of measuring points, run the program, and test voltage around the fishbone well. The measurement points were arranged on a uniform grid with a spacing of 5 cm in both the X and Y directions. Data were recorded once both the voltage and current readings had stabilized, and the values reported represent the average of three repeated measurements to ensure reliability.

- (6)

- Drawing equipotential lines. Process relevant data and draw equipotential lines by Surfer12.

- (7)

- Convert the measured current values into corresponding well productivity according to similarity principles and compare productivity among different well types.

- (8)

- Change various structural parameters of the fishbone well and repeat the above experimental steps.

2.4. Experimental Condition

2.4.1. Experimental Parameters

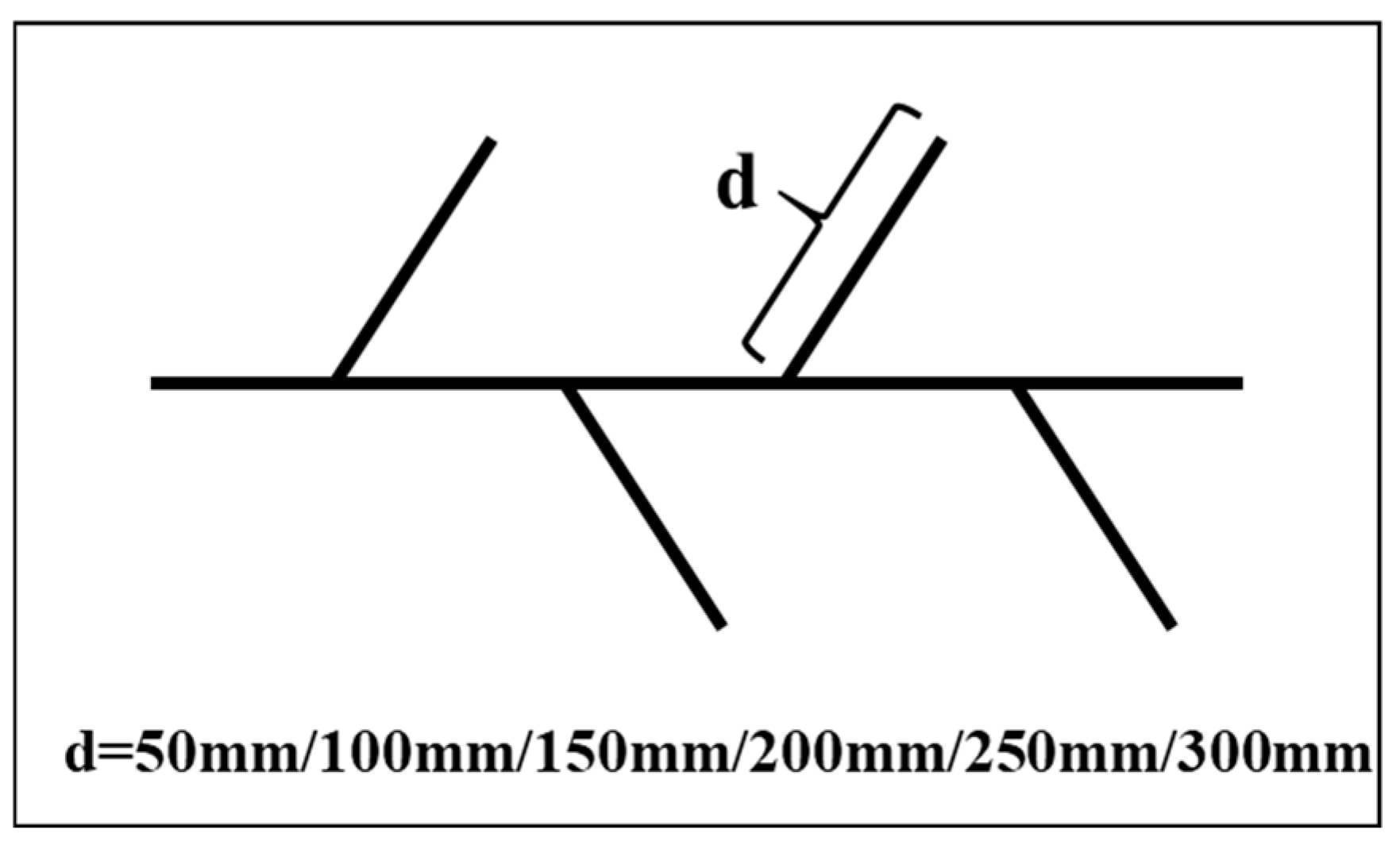

2.4.2. Experimental Model Design

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. The Productivity Interference Characteristics of Fishbone Well

3.1.1. Definition of Productivity Interference Coefficient

3.1.2. Influence of Number of Branches on Fishbone Well Productivity Interference

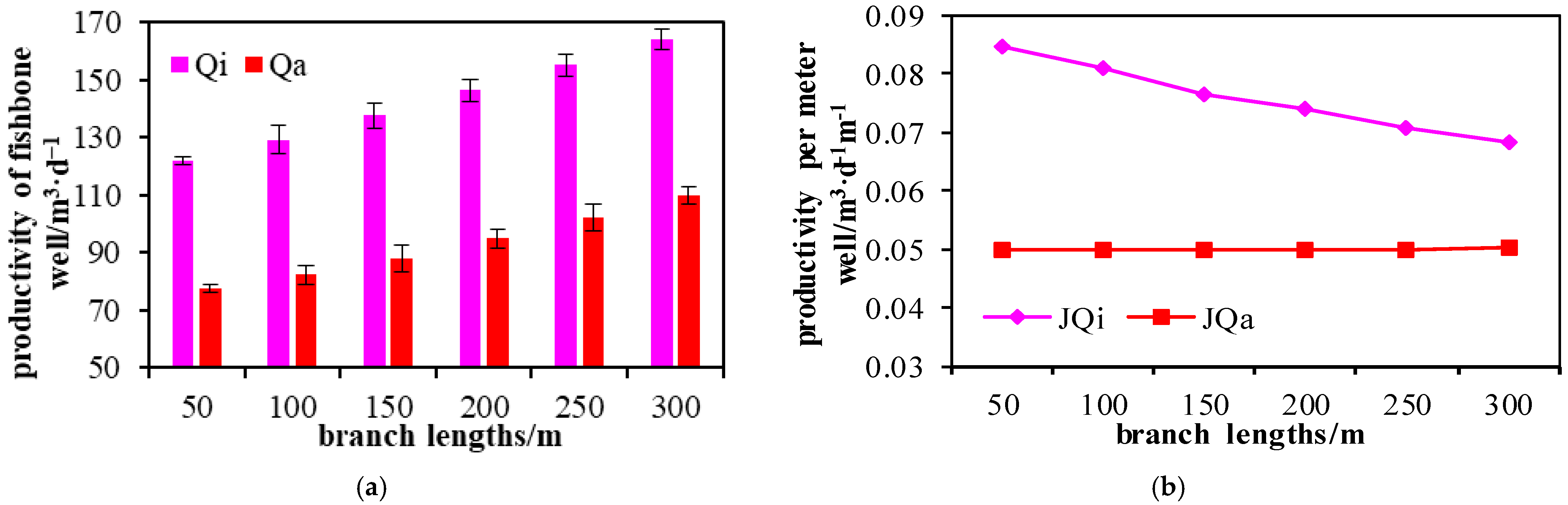

3.1.3. Influence of Branch Length on Fishbone Well Productivity Interference

3.1.4. Influence of Branch Angle on Fishbone Well Productivity Interference

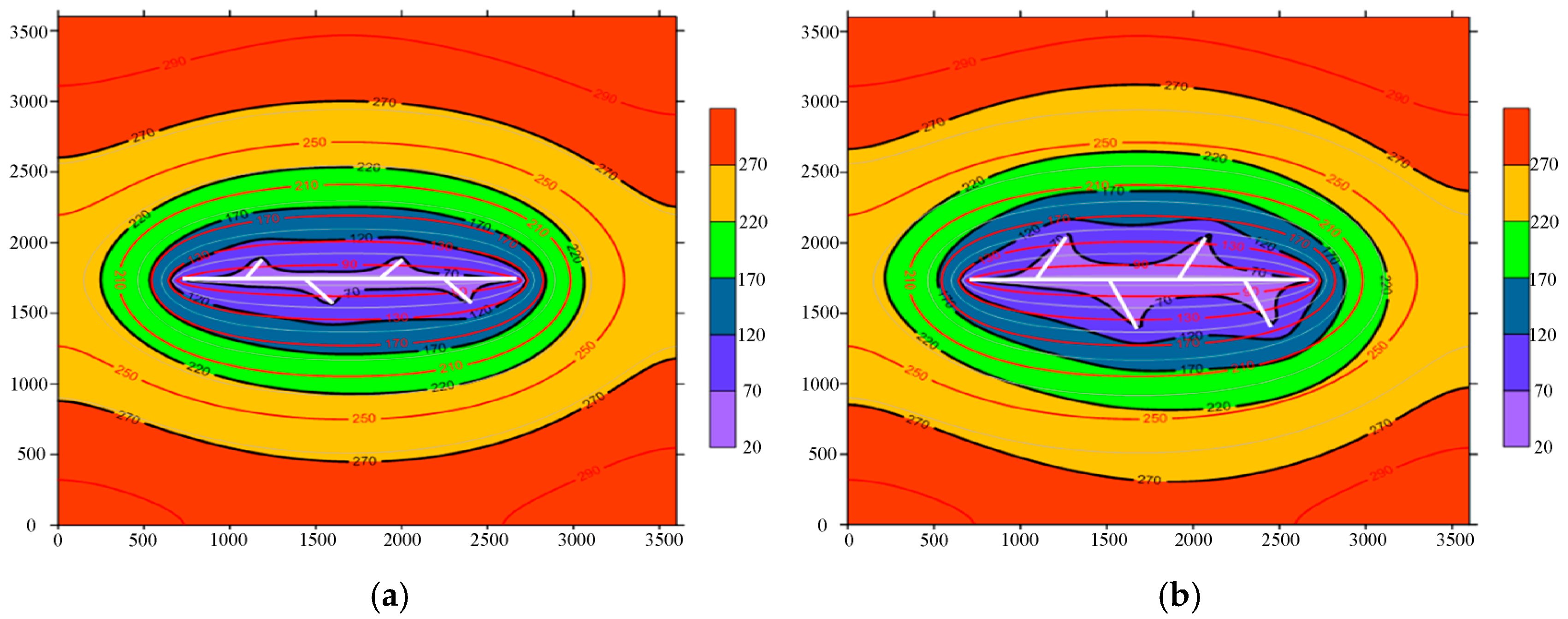

3.2. The Pressure Distribution Characteristics of Fishbone Well

3.2.1. Definition of Pressure Propagation Coefficient of Fishbone Well

3.2.2. Analysis of Influence of Branch Length on Pressure Propagation of Fishbone Well

3.2.3. Analysis of Influence of Branch Angle on Pressure Propagation of Fishbone Well

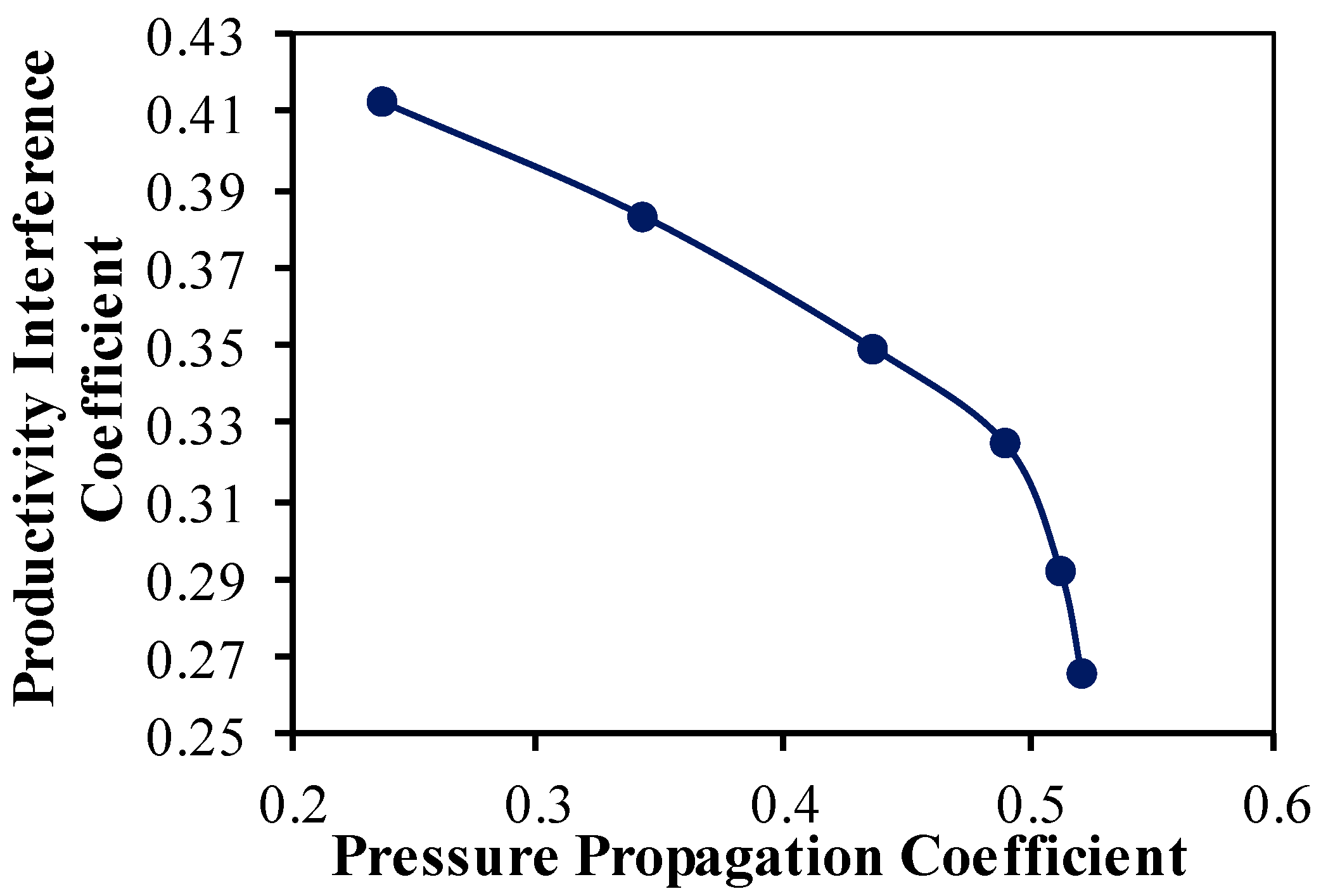

3.2.4. Analysis of Influence of Pressure Propagation Coefficient of Fishbone Well on Productivity

4. Conclusions

- The concepts of productivity interference coefficient and pressure propagation coefficient are proposed to quantify the productivity interference degree and pressure propagation range of fishbone wells.

- With the increase in the number of branches, the productivity interference coefficient between branches increases continuously. The productivity interference coefficients decrease with the increase in branch length and branch angle.

- The pressure propagation coefficients of both near-well zone and far-well zone increase with the increase in branch length and branch angle. The overall pressure propagation coefficient of far-well zone is greater than that of near-well zone.

- Productivity interference between branches is caused by pressure interference. By increasing the spacing between branches, the pressure propagation range expands and the productivity interference degree reduces.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Du, B.; Cheng, L.; Huang, S. Study on electrolytic simulation experiment of segmented multi-cluster fractured horizontal well in tight oil reservoir. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2013, 13, 3267–3270. [Google Scholar]

- Denney, D. Multilateral Well in Low-Productivity Zones. J. Pet. Technol. 1998, 50, 42–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mody, R.K.; Coronado, M.P. Multilateral Wells: Maximizing Well Productivity. In Pumps and Pipes: Proceedings of the Annual Conference; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2010; pp. 71–86. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Liu, H.; Jia, J. Hydroelectric simulation test of coalbed methane in symmetric multi branch horizontal wells. Coal Sci. Technol. 2023, 50, 135–142. [Google Scholar]

- Cavender, T. Summary of Multilateral Completion Strategies Used in Heavy Oil Field Development. In Proceedings of the SPE Western Regional Meeting, Bakersfield, CA, USA, 16–18 March 2004; p. SPE-86926-MS. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, G.; Guo, F.; Song, C.; Sun, Y.; Yu, J.; Wang, G. Fishbone Well Drilling and Completion Technology in Ultra-Thin Reservoir. In Proceedings of the IADC/SPE Asia Pacific Drilling Technology Conference and Exhibition, Tianjin, China, 9–11 July 2012; p. SPE-155958-MS. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, Y.; Hai, L.; Wang, A.; Wu, M. Technique of horizontal multilateral Well CB26B-ZP1 in Shengli Oilfield. Pet. Drill. Tech. 2007, 35, 52. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J. Drilling and completion technology of two-branch multi-lateral Xiao35-H1Z well in Liaohe Oilfield. Oil Drill. Prod. Technol. 2008, 30, 17–20. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, C.; Tong, K.; Zhou, F. Research on Flow Mechanism of Fishbone Well in Heavy Oil Field and Evaluate Its Development in Bohai Bay Heavy Oil Fields. Phys. Numer. Simul. Geotech. Eng. 2016, 24, 84–94. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Li, J.; Lv, D.; Kok, J.; Han, S.Y. Succeeding with Multilateral Wells in Complex Channel Sands. In Proceedings of the SPE Asia Pacific Oil and Gas Conference and Exhibition, Jakarta, Indonesia, 30 October 2007; p. SPE-110240-MS. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, C. Productivity Evaluation and Injection-Production Optimization of Multilateral Wells. Master’s Thesis, China University of Petroleum (East China), Dongying, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, D. Research on the Deliverability and Interference of Multilateral Well. Master’s Thesis, Northeast Petroleum University, Daqing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.; Huang, Y. Electrical simulation experiment of the seepage of zone near the borehole in symmetric herringbone wells. Contemp. Chem. Ind. 2017, 46, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, P.; Zhou, J.; Kang, L.; Liu, P.; Jia, C.; Chen, X. Reservoir and wellbore flow coupling model for fishbone multilateral wells in bottom water drive reservoirs. J. Energy Resour. Technol. 2021, 143, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.W. Experimental study on hydraulic fracturing simulation of horizontal well fracturing on well production. Energy Environ. Prot. 2017, 39, 167–170. [Google Scholar]

- Su, G.D.; Zhang, P.; Gu, X.; Han, B.Y.; Yi, P.; Li, M.Y. Design of Virtual Teaching Platform for Hydroelectric Simulation Experiment. Lab. Res. Explore 2018, 37, 105–109. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, G.F.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, M.; Xu, C.Z. Electric simulation of seepage flow for tight-oil horizontal well staged fracturing and considering start-up pressure. Energy Environ. Prot. 2019, 41, 64–67. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.C.; Liu, Z.L.; Ji, G.F.; Liu, Z.T.; Xu, Z. Hydro-electric Simulation of the Influence of Fracture Parameters on Seepage in Horizontal Wells After Fracturing in Tight Oil Reservoirs. Contemp. Chem. Ind. 2020, 49, 2736–2741. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, T.D. Study on Flow Law of Complex Fracture Network in Tight Reservoir. Master’s Thesis, China University of Petroleum, Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, M.; Wu, X.; Han, G.; Gao, F.; Xu, L.; Cao, G. Study on multi-lateral wells productivity based on electric analogy. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2012, 45, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; Sui, X.; An, Y.; Zhang, F.; Chen, Y. Electrolytic simulation experiment of fractured horizontal well. Acta Pet. Sin. 2009, 30, 740–743, 748. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, L.; Han, G.; Zhang, R.; Zhao, H.; Song, Y. A new approach of 3D potential distribution experiment for multi-lateral wells. J. Southwest Pet. Univ. (Sci. Technol. Ed.) 2015, 37, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Li, K.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, G.; Zhou, W.; Wang, K.; Liang, H. A new method for calculating the characteristic shape of the water ridge under horizontal production wells in marine sandstone heavy oil reservoirs with bottom water. Chem. Technol. Fuels Oils 2021, 57, 690–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, G.F.; Liu, Z.Q.; Zhao, W.W.; Nan, C.Y. Similarity simulation of tight oil horizontal well post-fracturing productivity based on principle of hydropower similarity. J. Heilongjiang Univ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 34, 440–445. [Google Scholar]

| Similarity Coefficient Name | Definition |

|---|---|

| Geometric similarity coefficient | |

| Pressure similarity coefficient | |

| Drag coefficient | |

| Rate similarity coefficient | |

| Flow similarity coefficient |

| Reservoir Parameters | Value | Experimental Parameters | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reservoir scale/m | 160 × 160 × 20 | Model size/m | 0.8 × 0.8 × 0.1 |

| Wellbore diameter/mm | 2000 | Wellbore diameter/mm | 1 |

| Main branch length/m | 1200 | Main wellbore length/m | 0.6 |

| Permeability/×10−3 μm2 | 1000 | Solution conductivity/μs·cm−1 | 356 |

| Drawdown pressure/MPa | 1.5 | Supply voltage/V | 12 |

| Viscosity(crude)/mPa·s | 10 |

| Similarity Coefficient Name | Value |

|---|---|

| Geometric similarity coefficient/µm2·[(mPa·s)·(µs/cm)]−1 | 5 × 10−3 |

| Drag coefficient Cr/µm2·[(mPa·s)·(µs/cm)]−1 | 46.81 |

| Pressure similarity coefficient Cp/V·(Mpa)−1 | 8 |

| Rate similarity coefficient Cρ/(µs/cm)·[mPa·s·(10−3 µm2)−1] | 0.171 |

| Flow similarity coefficient | 4.272 |

| Branch Lengths | F1 | F2 |

|---|---|---|

| 50 m | 0.097 | 0.236 |

| 100 m | 0.099 | 0.342 |

| 150 m | 0.103 | 0.436 |

| 200 m | 0.109 | 0.49 |

| 250 m | 0.113 | 0.512 |

| 300 m | 0.115 | 0.521 |

| Branch Angles | F1 | F2 |

|---|---|---|

| 15° | 0.098 | 0.286 |

| 30° | 0.102 | 0.411 |

| 45° | 0.106 | 0.463 |

| 60° | 0.109 | 0.49 |

| 75° | 0.111 | 0.514 |

| 90° | 0.113 | 0.528 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dang, X.; Huang, S.; Zhai, L.; Yuan, B.; Jiang, M. Experimental Study on Electrolytic Simulation of Production Capacity Interference in Asymmetric Fishbone Wells. Processes 2026, 14, 179. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010179

Dang X, Huang S, Zhai L, Yuan B, Jiang M. Experimental Study on Electrolytic Simulation of Production Capacity Interference in Asymmetric Fishbone Wells. Processes. 2026; 14(1):179. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010179

Chicago/Turabian StyleDang, Xu, Shijun Huang, Liang Zhai, Bin Yuan, and Mengchen Jiang. 2026. "Experimental Study on Electrolytic Simulation of Production Capacity Interference in Asymmetric Fishbone Wells" Processes 14, no. 1: 179. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010179

APA StyleDang, X., Huang, S., Zhai, L., Yuan, B., & Jiang, M. (2026). Experimental Study on Electrolytic Simulation of Production Capacity Interference in Asymmetric Fishbone Wells. Processes, 14(1), 179. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010179