1. Introduction

Against the backdrop of the global energy transition and low-carbon economic development, nuclear energy—as a clean and efficient energy source—has been progressively increasing its share in the global energy supply, driving a rising demand for uranium resources [

1]. Compared to conventional uranium mining methods, in situ leaching (ISL) uranium mining technology offers distinct advantages, including the ability to exploit low-grade deposits, simpler construction, cost-effectiveness, and faster production cycles. These benefits have garnered widespread attention in the international nuclear energy industry, establishing ISL as one of the pivotal technologies in modern uranium extraction practices [

2].

ISL uranium mining is primarily conducted through a system of engineered boreholes, including injection wells and extraction wells spaced at specific intervals. The core process involves pumping a formulated lixiviant (leaching solution) into the injection wells, which selectively reacts with subsurface uranium deposits, dissolving the metal into solution. The uranium-bearing liquid is then extracted via the extraction wells, pumped to the surface, and subjected to engineered chemical processes in surface facilities to recover uranium [

3,

4]. Currently, ISL accounts for approximately 50% of global uranium production annually [

5].

However, ISL uranium mining faces critical technical challenges such as imprecise control of injection volumes, suboptimal leaching efficiency, and groundwater contamination caused by chemical solvents. These issues constrain the technology’s operational efficiency and environmental sustainability, hindering its broader industrial adoption [

6,

7]. With the rapid advancement of artificial intelligence, particularly breakthroughs in machine learning for data-driven pattern recognition and process optimization, innovative approaches are being explored to mitigate these persistent challenges in ISL operations.

Currently, machine learning technologies have been widely applied to various aspects of ISL uranium mining, including ore deposit exploration, mining process optimization, environmental monitoring, and evaluation. For example, Mukhamediev [

8] in Kazakhstan used machine learning methods to estimate the filtration characteristics of host rocks in sandstone-type uranium deposits, providing a scientific basis for mining; Merembayev [

9] employed machine learning algorithms to classify strata of uranium deposits; Amirgaliev [

10] applied several machine learning methods to identify rocks in uranium deposits; and Mukhamediev [

11] utilized machine learning methods to determine the formation of oxidized zones in uranium well reservoirs.

With the rapid development of the nuclear energy industry, research on ISL uranium mining technology and its optimization methods has garnered increasing attention. Li et al. [

12] developed a coupled model to simulate and optimize fluid flow in a complex well-formation system for ISL uranium mining. Jia et al. [

13] devised an enhanced fast marching method (FMM), this method was studied for rapidly analyzing solute transport coverage patterns, offering an alternative to groundwater numerical simulators. At the same time, numerous research institutions and universities have extensively explored the application of machine learning to ISL technology. For example, Dongyuan Yu [

14] developed machine learning-based methods to predict variations in uranium leaching rate during ISL processes, while Lei Lin [

15] employed neural network models to forecast uranium concentration of acid in situ leach liquor. These studies focus not only on optimizing extraction processes—such as predicting and adjusting injection strategies through machine learning algorithms—but also extend to environmental monitoring and assessment, utilizing machine learning models to predict and evaluate potential environmental impacts of mining activities.

Despite progress in applying machine learning to ISL uranium mining, significant challenges remain. A critical technical priority is optimizing injection strategies to improve uranium leaching rates and recovery rates—an effort closely tied to the overarching goal of efficient resource utilization. To address this, we propose an attention-based CNN–LSTM–LightGBM fusion model for the precise prediction of uranium leaching rates in ISL operations. Building on these predictions, the model provides targeted support for optimizing uranium recovery processes. By clarifying the relationships between key parameters in the leaching process—such as daily lixiviant volume and sulfuric acid concentration—and leaching efficiency, it helps adjust core operations like injection strategies. This, in turn, indirectly enhances uranium recovery rates while meeting the current demand for efficiency in ISL resource recovery [

16,

17]. The proposed approach offers actionable guidance for improving leaching performance and ensuring consistency with engineering expectations.

2. CNN–LSTM LightGBM Fusion Model

2.1. Construction of the Coupled CNN–LSTM Model

The proposed uranium leaching rate prediction model consists of three core layers—a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network, and an attention mechanism layer—which analyze influencing factors in the uranium leaching process.

2.1.1. Convolutional Neural Network

The core strength of Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) in time-series prediction lies in their ability to efficiently capture local temporal dependencies and hierarchical patterns within sequential data—particularly through one-dimensional (1D) convolutional layers, which are tailored for processing time-series inputs. As a feedforward neural network with trainable convolutional kernels [

18], CNNs excel in extracting meaningful features from ordered temporal sequences by sliding 1D filters (convolution kernels) along the time axis. This sliding operation enables element-wise multiplication and summation across consecutive time steps, generating feature maps that encode critical local patterns such as short-term fluctuations, periodic pulses, or transient trends in the time series.

By stacking multiple 1D convolutional layers, the network progressively aggregates these local temporal features into higher-level representations—for example, linking hourly leaching rate variations to daily or weekly trend patterns—thereby capturing both fine-grained dynamics and coarse-grained temporal structures [

19,

20,

21]. Compared to fully connected networks or traditional time-series models, CNNs reduce parameter redundancy through weight sharing in convolutional kernels, enhancing computational efficiency even for long time-series data [

22]. One-dimensional (1D) convolutional layers extract temporal features along the time axis, with their output as Equation (1).

where

is the input time series;

is the weight matrix of the convolution kernel;

is the bias; and

is the number of convolution kernels.

2.1.2. LSTM Neural Networks

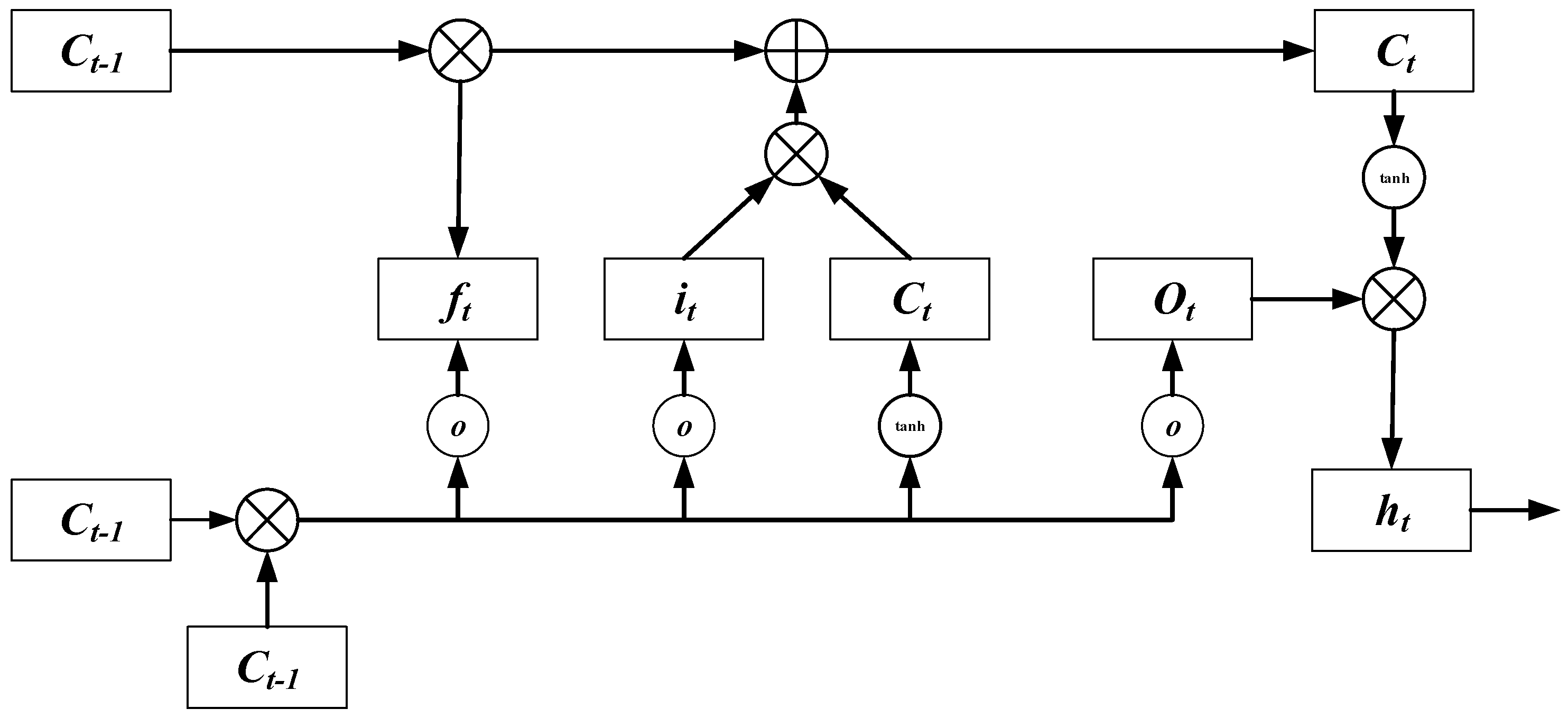

Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) neural networks [

23] are a specialized variant of Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) designed specifically to address challenges in modeling long-sequence data. As a significant innovation in deep learning, they aim to handle and analyze long-term dependency issues in time-series data. The structure of the LSTM recurrent unit is illustrated in detail in

Figure 1.

Compared to standard RNNs, the basic neural unit of LSTM adds three “gates”: the input gate

, forget gate

, and output gate

, whose coefficient values range between [0, 1]. The input gate primarily determines which attributes need to be updated and the content of new attributes; the forget gate aims to discard previous useless state information; the output gate decides what to output. These three gates are all outputs from the previous unit

and the current input

at any time step, collectively determining the final output [

24]. The calculation formulas for the input gate

, forget gate

, output gate

, and the candidate cell state

are given in Equations (2)–(5).

Here, , , , , , , , and denote the weight matrices obtained by multiplying the corresponding gates with the current input and the previous unit output . , , , and are bias terms, and σ represents the sigmoid function.

The updated state value

is determined by the previous state value

, the forget gate

, the input gate

, and the candidate cell state

. Following the state update, the output value

can be computed in the form of element-wise multiplication, as shown in Equations (6) and (7).

2.1.3. Attention Mechanism

The fundamental idea of the attention mechanism is to filter useful information. Its essence in achieving this effect lies in computing the output sequence of the LSTM hidden layer—specifically, the input feature vectors post-training—to derive a feature weight vector. This process identifies more critical influencing factors, thereby enhancing the efficiency and accuracy of information processing [

25]. The specific architectural diagram is illustrated in

Figure 2.

The steps for computing the feature weight vector are as follows. First, we calculate the attention weight

assigned to the element at the current time step

t within the output sequence of the LSTM hidden layer. In Equation (8),

denotes the sequence number in the output sequence of the LSTM hidden layer,

represents the sequence length of the LSTM hidden layer output, and

indicates the matching degree between the element to be encoded and other elements in the LSTM hidden layer output sequence. Subsequently, the feature weight vector

is computed using Equations (8)–(10).

Here, H(⋅) denotes the feature weight vector function; represents the output sequence of the LSTM hidden layer; and corresponds to the hidden state of the attention mechanism associated with the output sequence of the LSTM hidden layer.

2.1.4. Construction of the Fusion Model

The architecture of the CNN–LSTM fusion model integrated with the attention mechanism is illustrated in

Figure 3.

The model first transforms historical data related to uranium leaching rates (including daily production volume, daily lixiviant volume, H2SO4 lixiviant concentration, and uranium concentration in the lixiviant) through preprocessing steps into 1D vectors with a length of 5 and a height of 1. This approach leverages the advantage of CNNs in image feature extraction.

In this architecture, the convolutional kernel size is set to 1, and the ReLU function is employed as the activation function. The LSTM layer, designed to process long-sequence data, incorporates two hidden layers with 64 units each, where the ReLU activation function is also applied. However, individual models have their respective limitations: CNNs excel at capturing local features but struggle to model long-term dependencies, while LSTMs have an advantage in long-time-series analysis but lack the ability to focus on key local features. An attention module is introduced after the LSTM network to compute the weights, ultimately deriving the prediction results.

Overall, this coupled architecture exactly addresses the aforementioned limitations: it combines the spatial feature extraction capabilities of CNNs, the time-series analysis capabilities of LSTMs, and the selective focusing capability of the attention mechanism. It enables a holistic comprehension and analysis of multiple factors influencing the uranium leaching process. The approach not only enhances predictive accuracy but also deepens the model’s understanding of interactions among complex geological and chemical variables.

2.2. LightGBM

LightGBM was first introduced in [

26] and has since been widely adopted. LightGBM, short for ‘Light Gradient Boosting Machine’, is an efficient machine learning framework based on Gradient Boosting Decision Tree (GBDT). As an extension of GBDT, LightGBM adopts a histogram-based decision tree algorithm. By reducing memory usage and improving computational efficiency, it significantly accelerates training speed and decreases memory consumption. The core idea of LightGBM is to linearly combine M weak regression trees into a strong regression tree. The computational formula is provided in Equation (11).

Here,

represents the final output, and

denotes the output of the m-th weak regression tree. The key improvements in the LightGBM model include the histogram-based algorithm and the leaf-wise splitting strategy. The histogram algorithm discretizes continuous data into K integer intervals and constructs a histogram with a width of K. During traversal, the discretized values are used as indices to accumulate statistics in the histogram, followed by a search for the optimal split points in the decision tree. The leaf-wise splitting strategy iteratively selects the leaf node with the maximum gain for splitting. Additionally, model complexity is reduced, and overfitting is mitigated by constraining the depth of the trees and the number of leaf nodes [

27].

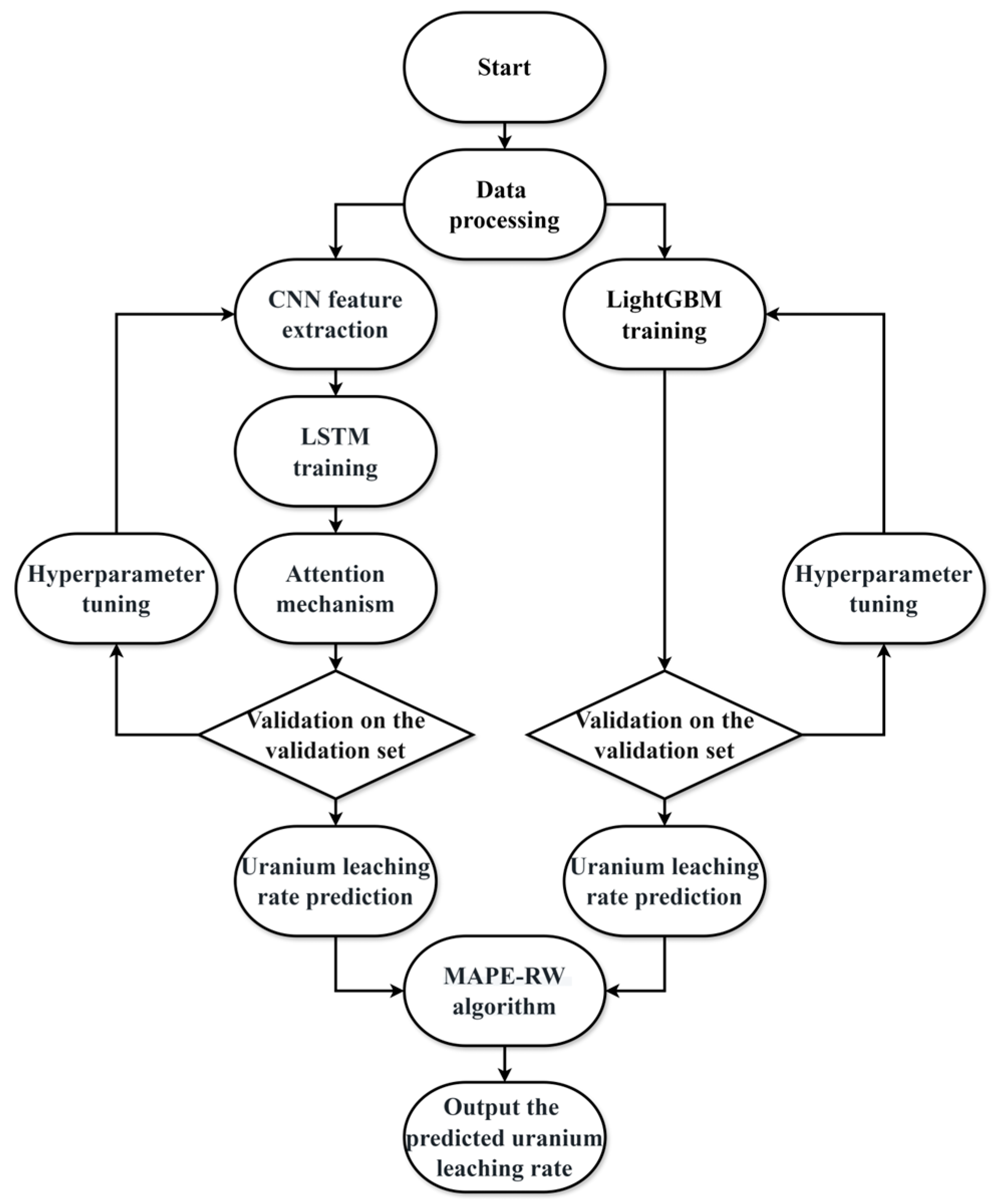

2.3. Training Process of Fusion Models

The flowchart of the training process for the CNN–LSTM–LightGBM-based fusion model with attention mechanism, designed for predicting leaching rates in ISL uranium mining, is illustrated in

Figure 4.

Based on the data features extracted by the CNN, the CNN–LSTM model and the LightGBM model are constructed separately, and a fusion prediction model is established through weighted fusion. The MAPE-RW algorithm is employed to calculate the initial weights of individual models. First, the CNN–LSTM model and the LightGBM model are trained, and their respective MAPE values on the validation set are computed. Subsequently, the model weights are optimized via the MAPE-RW algorithm, and the uranium leaching rate prediction from the fusion model is output as the final result.

The MAPE-RW algorithm calculates model weights through the following procedure: First, the MAPE values of the CNN–LSTM model and the LightGBM model are computed separately to determine the initial weights for each individual model. Then, the model weights are iteratively adjusted in both directions until the weights that minimize the MAPE value are identified. The optimal weights within the bidirectional search range that yield the smallest MAPE value are ultimately selected as the optimal weights for the fusion prediction model. Finally, the combined uranium leaching rate prediction is calculated using Equations (12)–(14).

Here, and represent the MAPE values of the CNN–LSTM model and the LightGBM model, respectively. and denote the initial weights assigned to the two models. The coefficients and are the optimized weights for the CNN–LSTM and LightGBM models, respectively. and correspond to the predicted uranium leaching rates from the CNN–LSTM and LightGBM models, while is the final prediction of the uranium leaching rate generated by the fusion model. The proposed model employs the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) to evaluate its effectiveness against traditional strategies.

3. Data Preprocessing

3.1. Handling Missing Values and Outliers

In this study, we adopted the widely recognized multiple imputation (MI) technique to address the unavoidable issue of missing values in the dataset. The principle of MI is grounded in the assumption that the missing data mechanism is Missing at Random (MAR), meaning the probability of missingness depends solely on observed data and is independent of unobserved data. The MI process can be broadly divided into three stages: Imputation, Analysis, and Pooling. In scenarios involving complex missing data patterns or high missingness proportions, MI provides an effective solution [

28].

Outliers in the following six metrics were processed via the clipping method: Uranium Concentration in the Production Solution, Uranium Concentration in the Lixiviant, H2SO4 Lixiviant Concentration, Metal Concentration in the Lixiviant, Daily Production Volume in the acid leaching process, and Daily Lixiviant Volume in the acid leaching process. Clipping is a statistical method for handling outliers, with the primary objective of trimming values that exceed predefined thresholds by capping them within upper and lower bounds.

After data cleaning, the coefficients of variation (CV) for all six metrics—H2SO4 Lixiviant Concentration (0.135), Uranium Concentration in the Lixiviant (0.119), Uranium Concentration in the Production Solution (0.142), Metal Concentration in the Lixiviant (0.012), Daily Production Volume (0.062), and Daily Lixiviant Volume (0.078)—remained below 0.15, confirming the effectiveness of outlier clipping.

3.2. Indicator Correlation Analysis

This study employs the Pearson correlation coefficient [

29] and Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient [

30] among various correlation coefficients for analysis, integrating the analytical results from both methods to conduct a comprehensive analysis.

The formula for the Pearson correlation coefficient can be represented by Equations (15) and (16).

where

x and

y represent the time series of the two selected reference variables,

denotes the covariance between sequence

x and reference sequence

y, and

and

represent the mean values of sequences

x and

y, respectively. Additionally,

serves as the index of the time series, indicating the actual value at each time point. A correlation coefficient

< 0 indicates a negative correlation between variables, while a correlation coefficient

> 0 suggests a positive correlation. When the absolute value of the correlation coefficient between variables exceeds 0.5, it can be considered that a strong correlation exists.

In the analysis of the ISL uranium mining process, six indicators were preliminarily selected. A code-based computational approach was employed to calculate the correlation coefficients among these six indicators within the dataset. The resulting correlation coefficients are visualized in

Figure 5a. The heatmap reveals that, for the uranium concentration in the leachate, the highest correlations are observed with daily production volume and daily lixiviant volume, yielding values of 0.48 and 0.54.

To validate the robustness of indicator correlations, a non-parametric method—Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient—was further employed for multi-method validation, aiming to assess the presence of significant monotonic associations among the indicators. This coefficient, proposed by Spearman [

31], is defined by Equation (17) and serves to quantitatively analyze the direction and strength of monotonic associations between variables.

In Equation (17),

represents Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient. The calculation of this coefficient involves several key elements:

, where

denotes the difference in ranks between variables

and

, and

refers to the total sample size. The Spearman correlation coefficients for the technical indicator data were further computed, and the results are visualized in

Figure 5b.

According to the Spearman correlation heatmap, the positively correlated indicators align with the results from the Pearson correlation analysis. Specifically, metal concentration in the lixiviant, daily lixiviant volume, daily production volume, and uranium concentration in the production solution exhibit positive correlations with uranium concentration in the lixiviant. Among these, the strongest correlation is observed between metal concentration in the lixiviant and uranium concentration in the lixiviant. In contrast, H2SO4 lixiviant concentration shows a weak negative correlation with uranium concentration in the lixiviant.

By integrating the results from both the Pearson and Spearman correlation heatmaps, a composite histogram of correlation indicators was generated (

Figure 6). As shown in

Figure 6, the daily lixiviant volume exhibits the highest correlation strength. The remaining indicators are ranked in descending order of correlation magnitude: metal concentration in the lixiviant, daily production volume, H

2SO

4 lixiviant concentration, and uranium concentration in the lixiviant.

3.3. XGBoost Feature Selection

To validate the correctness of Pearson and Spearman analyses on the five indicators, XGBoost feature selection was further used to rank the importance of all features in the dataset. XGBoost provides built-in feature importance evaluation methods for feature selection [

32]. The general steps for feature importance evaluation are as follows: 1. Train an XGBoost model. 2. Obtain importance scores of each feature using built-in functions (e.g., feature importance). 3. Rank features based on the scores and select the highest-ranked ones. By integrating data from all mining areas and constructing an XGBoost model, the importance of all features was calculated. The final ranking of feature importance, sorted in descending order, is shown in

Table 1.

As shown in

Table 1, the daily lixiviant volume exhibits the highest feature importance, indicating its greatest contribution to predicting uranium concentration in the production solution. In contrast to the Pearson and Spearman correlation analyses, the remaining features are ranked in descending order of importance as follows: daily production volume, followed by H

2SO

4 lixiviant concentration, then uranium concentration in the lixiviant, and finally metal concentration in the lixiviant. Notably, metal concentration in the production solution and H

2SO

4 production concentration showed minimal relevance. This trend is consistent with the correlations derived from chemical reaction equation analysis, further validating the dominance of the top five features. The final constructed feature set comprises the following variables: daily lixiviant volume, daily production volume, H

2SO

4 lixiviant concentration, uranium concentration in the lixiviant, and metal concentration in the lixiviant.

4. Experimental Analysis

4.1. Model Evaluation Metrics

The model was primarily evaluated using MAPE (Mean Absolute Percentage Error), RMSE (Root Mean Square Error), and MAE (Mean Absolute Error) as performance metrics.

MAPE is a commonly used metric for evaluating prediction accuracy. It calculates the average of the absolute percentage errors between predicted and actual values, which is then converted into a percentage to provide an intuitive understanding of the error magnitude. RMSE, another widely used measure, quantifies deviations between predicted and observed values. It is calculated as the square root of MSE. By preserving the original data units and reflecting error dispersion, RMSE enables direct comparisons across different scales. MAE measures the average absolute difference between the predicted and actual values, serving as a straightforward method for assessing the accuracy of a prediction model. The computational formulas for these metrics are provided in Equations (18)–(20).

where

represents the actual value at the

observation;

denotes the predicted value at the

observation; and

is the total number of observations.

4.2. Ablation Experiment

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed CNN–LSTM–LightGBM model for uranium leaching rate prediction, a series of performance tests was conducted on individual components (CNN, LSTM, and CNN–LSTM). The comparative results are summarized in

Table 2 and illustrated in

Figure 7.

As shown in

Table 2 and

Figure 8, the fused model achieves the best performance across three key metrics: MAE (0.085%), MAPE (0.833%), and RMSE (0.201%), demonstrating the lowest errors. The CNN–LSTM coupled model exhibits superior performance compared to standalone CNN and LSTM architectures across all metrics. This improvement likely stems from its ability to synergize CNN’s spatial feature extraction with LSTM’s temporal sequence modeling, thereby enhancing the accuracy of uranium leaching rate predictions.

The standalone LSTM model outperforms the standalone CNN model in terms of MAE and RMSE, likely due to LSTM’s inherent strength in processing time-series data and capturing temporal dependencies in uranium leaching processes. However, its performance remains inferior to the CNN–LSTM fusion, suggesting that relying solely on temporal analysis may be insufficient for comprehensively predicting uranium leaching rates, thus highlighting the necessity of integrating spatial features.

In contrast, the standalone CNN model demonstrates the weakest performance across all metrics, indicating that spatial feature extraction alone may lack accuracy in predicting uranium leaching rates without addressing complex temporal dependencies. This further emphasizes the critical role of temporal information and the need to combine it with spatial features for uranium leaching rate prediction.

These limitations highlight the necessity of hybrid modeling. The proposed fusion model outperforms all benchmarks on every metric, empirically showing that combining LightGBM with the CNN–LSTM architecture markedly improves prediction accuracy.

4.3. Comparative Experiments

To further validate the effectiveness of the fusion model, a comparative performance analysis was conducted between the proposed fusion model and six machine learning prediction models, including Support Vector Regression (SVR), Multilayer Perceptron (MLP), K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), and attention-based ResNet [

33], attention-based TCN-BiGRU [

34], and CNN-BiGRU fused with attention mechanisms [

35]. The experimental results (summarized in

Table 3) demonstrate that the fusion model consistently outperformed all alternatives across every evaluation metric.

As shown in

Table 3, the CNN–LSTM–LightGBM uranium leaching rate prediction model outperforms six heterogeneous and extensively utilized machine learning methods, such as SVR, MLP, and KNN, across all three key metrics on the validation set.

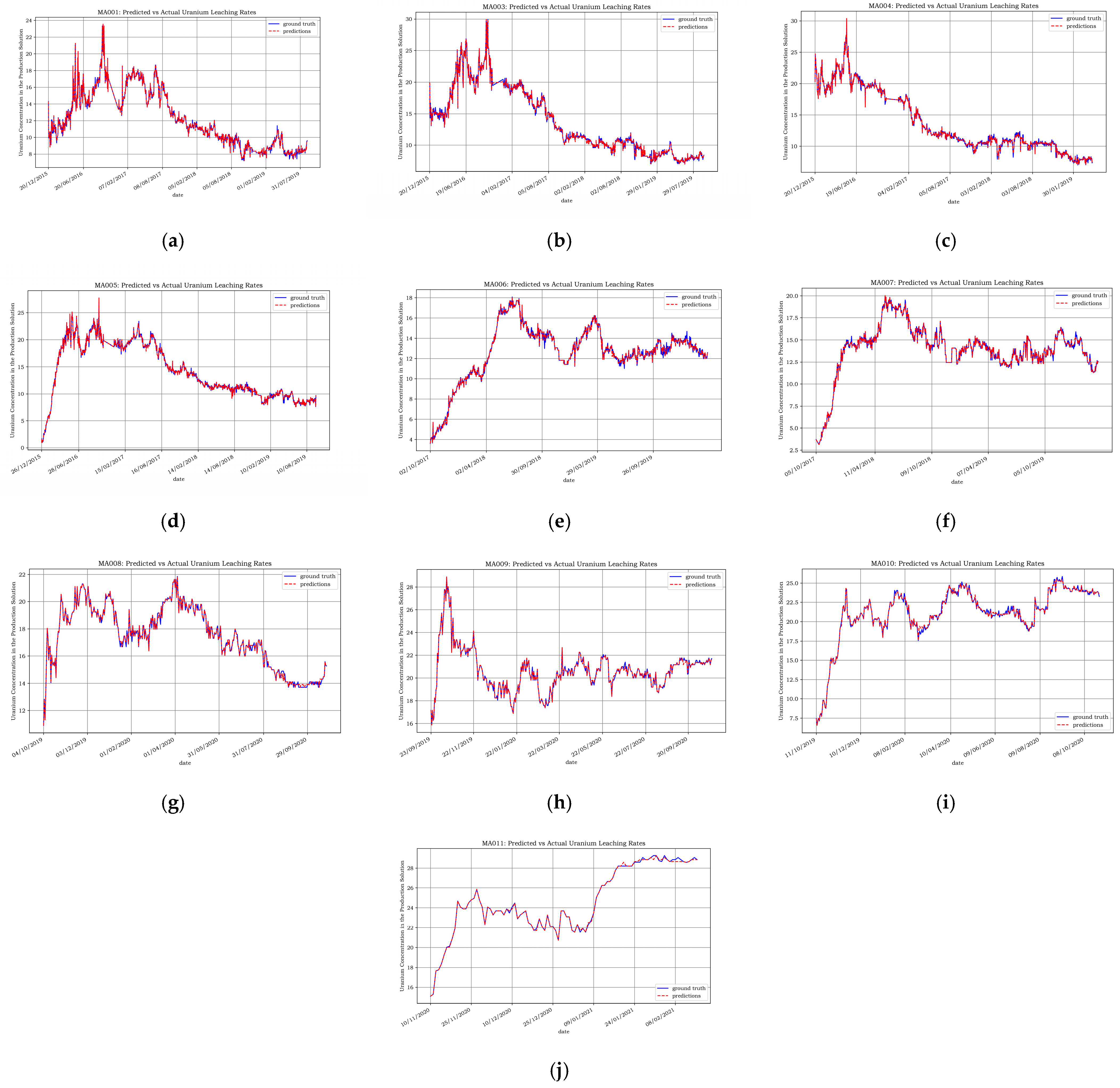

4.4. Model Application

To validate whether the model can be effectively applied in actual production, the proposed CNN–LSTM–LightGBM fusion model with attention mechanisms was used to predict uranium leaching rates across 10 mining areas. As shown in

Figure 9, the model achieved robust prediction accuracy across all mining areas, reliably forecasting uranium concentrations within operational tolerances.

The metric performance is shown in

Table 4: MAE had a maximum of 0.112% and a minimum of 0.039%; MAPE had a maximum of 0.985% and a minimum of 0.166%; RMSE had a maximum of 0.249% and a minimum of 0.105%.

5. Conclusions

The proposed CNN–LSTM–LightGBM fusion model with attention mechanisms provides reliable predictions of uranium leaching rates during in situ uranium leaching processes. Comparative experiments demonstrate that the proposed model achieves an MAE of 0.085%, an MAPE of 0.833%, and an RMSE of 0.201% on the validation set, outperforming six heterogeneous and extensively utilized methods, including SVR, MLP, and KNN across three metrics. Ablation experiments, which quantify component contributions through systematic exclusion, reveal the fusion model’s advantages in terms of MAE, MAPE, and RMSE on the validation set compared to standalone CNN, LSTM, and CNN–LSTM counterparts. The research outcomes, by enabling accurate prediction of uranium leaching rates and thereby optimizing lixiviant injection strategies, not only enhance the efficient utilization of uranium resources but also provide actionable insights for reducing environmental pollution. In conclusion, the proposed fusion model presents a deep learning-integrated approach for in situ uranium leaching technology, while offering a methodological reference for related industrial domains. This innovation holds significant potential for promoting the transformation of in situ leaching uranium mining technology toward a data-driven and optimization-oriented intelligent transformation.

There is still room for expansion in the dimensionality of data indicators for prediction and the coverage of mining area samples in this study’s model, and the depth of integration between the model and professional mechanistic knowledge, such as geological fluid dynamics, remains insufficient. Future work should focus on integrating the model with the full-process environmental impact assessment of in situ leaching uranium mining, quantifying the long-term effects of injection strategies on ecosystems such as groundwater, and exploring interdisciplinary integration with hydrological simulation and ecological risk assessment, so as to provide more systematic guarantees for in situ leaching uranium mining technology in moving toward a high-quality development direction featuring low environmental impact and high resource utilization.