Natural Carboxylic Acid Deep Eutectic Solvents: Properties, Bioactivities and Walnut Green Peel Flavonoid Extraction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Physicochemical Properties

2.1.1. Water Content

2.1.2. Polarity

2.1.3. Electrical Conductivity

2.1.4. Kamlet−Taft Parameters

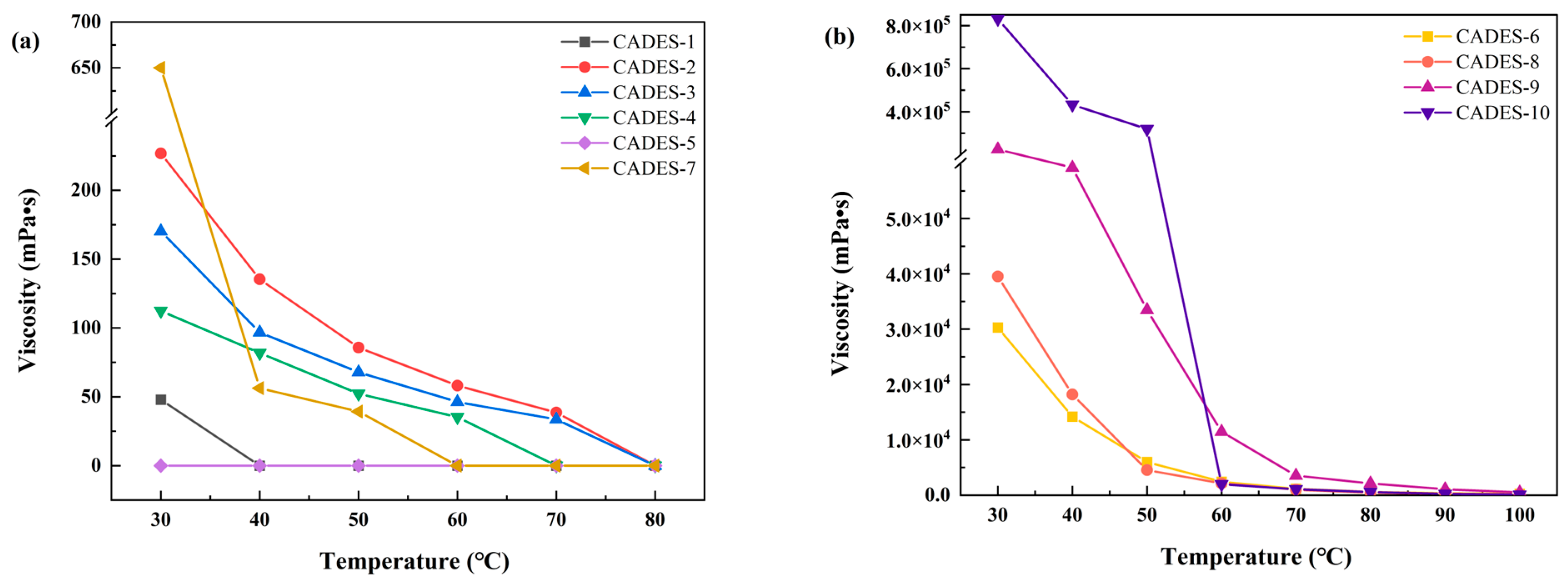

2.1.5. Viscosity

2.2. Antioxidant Property

2.2.1. DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity

2.2.2. ABTS Radical Scavenging Activity

2.2.3. Fe2+ Chelating Activity

2.3. Antibacterial Property

2.3.1. Antibacterial Zone

2.3.2. The MIC of CADESs

2.4. The CADES on the Germination Toxicity of Mung Beans

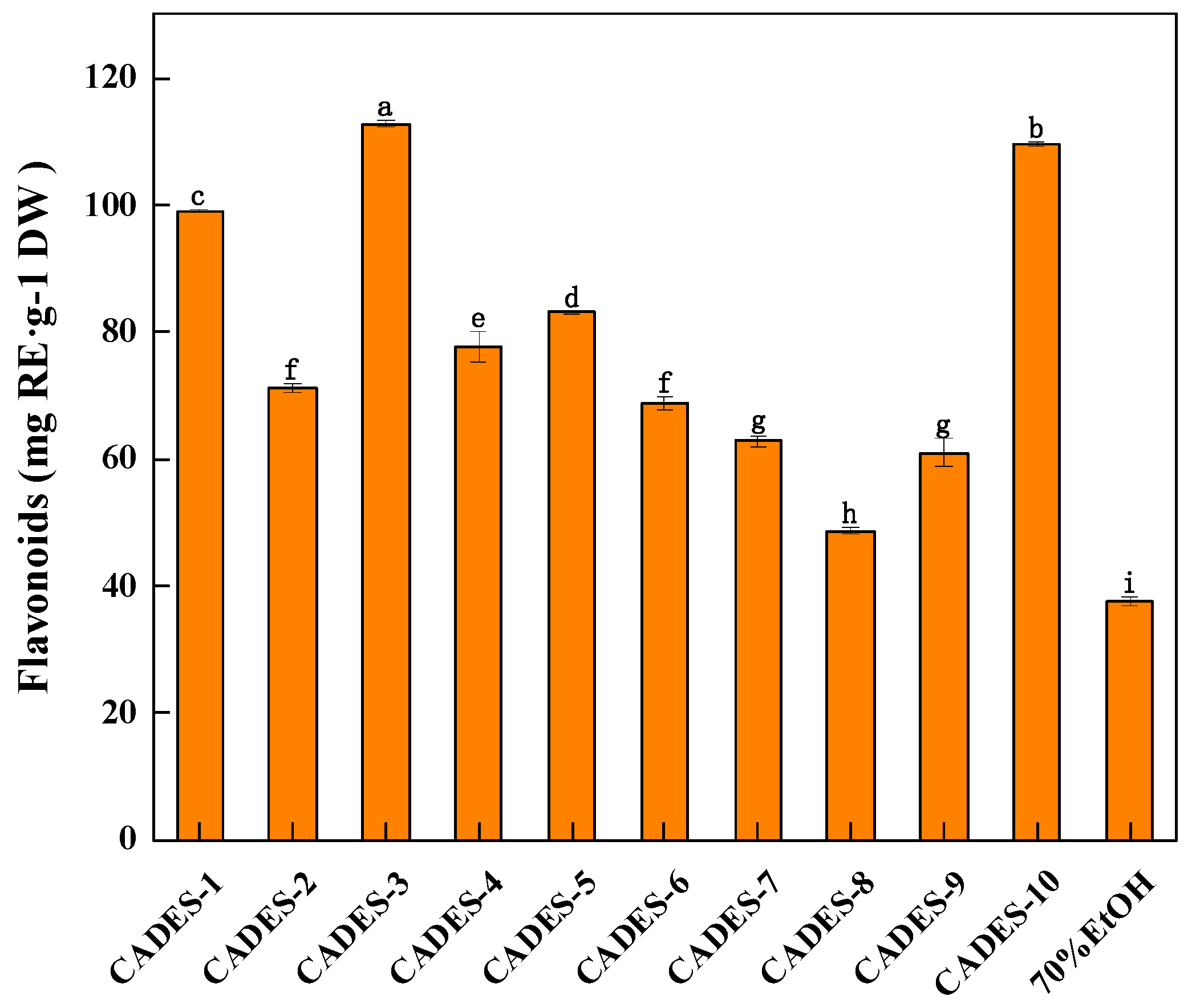

2.5. Extract Flavonoids from Walnut Green Peel Using CADESs

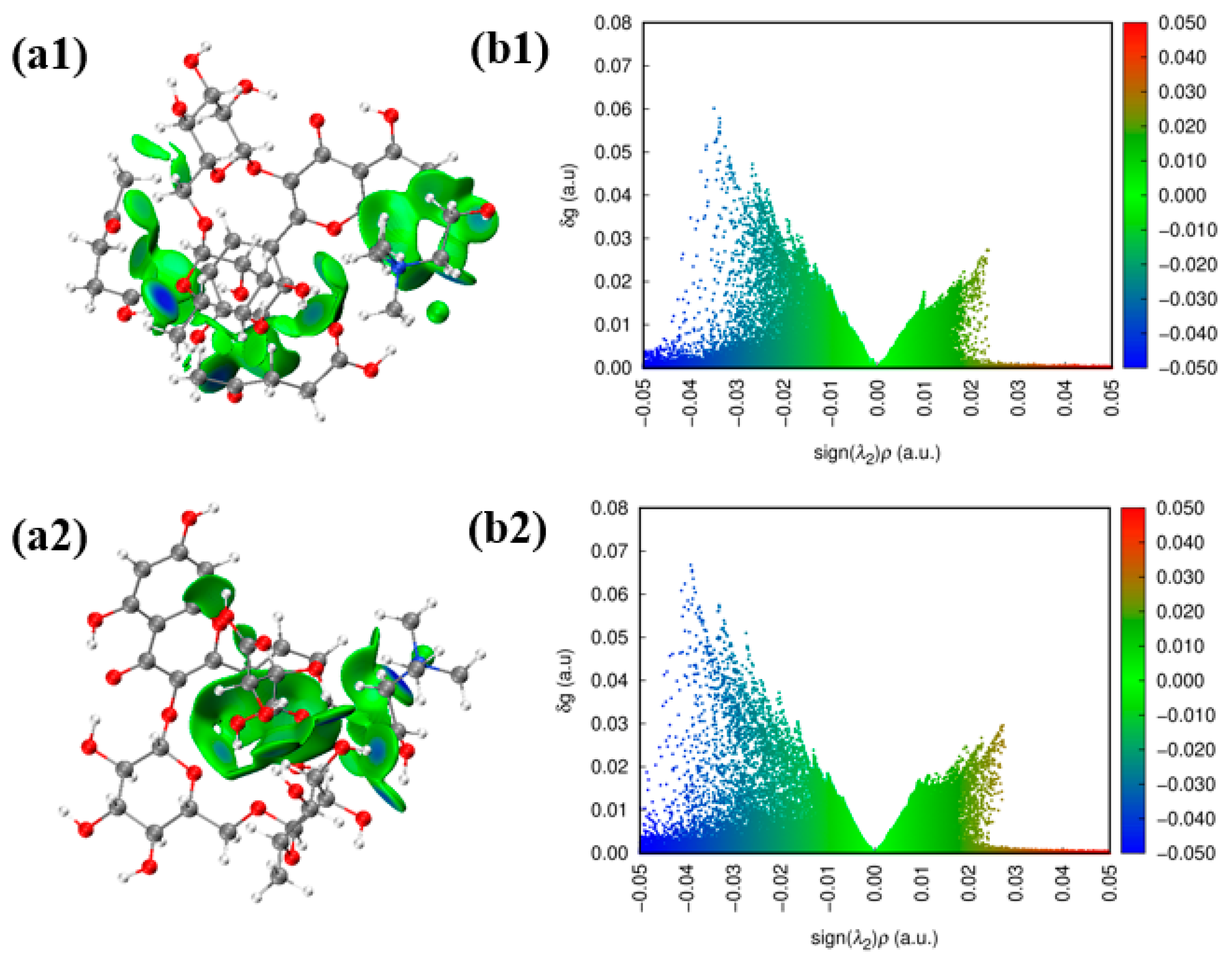

2.6. Interaction Between CADES and Rutin by IGMH

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemicals

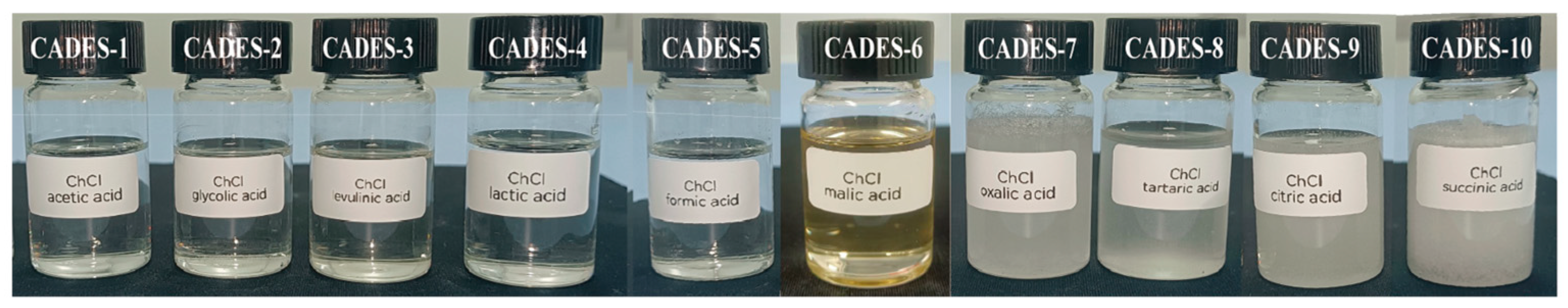

3.2. Preparation of CADESs

3.3. Physicochemical Properties

3.3.1. Kamlet-Taft Parameters Determination

3.3.2. Electrical Conductivity

3.3.3. Viscosity

3.3.4. Water Content

3.3.5. Polarity

3.4. Antioxidant Activity

3.4.1. DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity

3.4.2. ABTS Radical Scavenging Activity

3.4.3. Fe2+ Chelating Activity

3.5. Antibacterial Property

3.5.1. Antibacterial Zone

3.5.2. Determination of the MIC of CADES

3.6. The Impact of CADES on the Germination Toxicity of Mung Beans

3.7. Extraction and Determination of Flavonoids from Walnut Green Peel

3.8. Quantum Chemical Calculations

3.9. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DESs | Deep eutectic solvents |

| CADESs | Carboxylic acid-based deep eutectic solvents |

| NADESs | Natural deep eutectic solvents |

| HBAs | Hydrogen bond acceptors |

| HBDs | Hydrogen bond donors |

| ILs | Ionic liquids |

| ChCl | Choline chloride |

| DPPH | 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl |

| ABTS | 3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid |

| LB | Luria–Bertani |

| TFC | Total flavonoid content |

| MIC | Minimum inhibitory concentration |

| RGP | Relative germination rate |

| AGR | Average germination rate |

| HAT | Hydrogen atom transfer |

| mg RE·g−1 DW | mg Rutin Equivalent·g−1 Dry Weight |

References

- Smith, E.L.; Abbott, A.P.; Ryder, K.S. Deep eutectic solvents (DESs) and their applications. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 11060–11082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Q.H.; Cao, J.; Chen, L.Y.; Cao, J.R.; Wang, H.M.; Cao, F.L.; Su, E.Z. Solubilization of phytocomplex using natural deep eutectic solvents: A case study of Ginkgo biloba leaves extract. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2022, 177, 114455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.C.; Luo, H.; Zhu, C.Y.; Li, W.J.; Wu, D.; Wu, H.W. Hydrophobic natural alcohols based deep eutectic solvents: Effective solvents for the extraction of quinine. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 275, 119112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanda, H.; Dai, Y.T.; Wilson, E.G.; Verpoorte, R.; Choi, Y.H. Green solvents from ionic liquids and deep eutectic solvents to natural deep eutectic solvents. Comptes Rendus Chim. 2018, 21, 628–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.C.; Bo, Y.Y.; Liang, Y.H.; Lu, B.B.; Zhan, J.B.; Zhang, J.C.; Zhang, J.H. Intermolecular interactions in natural deep eutectic solvents and their effects on the ultrasound-assisted extraction of artemisinin from Artemisia annua. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 326, 115283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.Q.; Li, Z.H.; Liu, L.L.; Wang, H.; Yang, S.H.; Zhang, J.S.; Zhang, Y. Green extraction using deep eutectic solvents and antioxidant activities of flavonoids from two fruits of Rubia species. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 148, 111708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.J.; Liu, Z.T.; Chen, X.Q.; Zhang, T.T.; Zhang, Y. Deep eutectic solvent combined with ultrasound technology: A promising integrated extraction strategy for anthocyanins and polyphenols from blueberry pomace. Food Chem. 2023, 422, 136224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.J.; Wang, P.W.; Zhang, H.; Fan, Y.Y.; Cao, X.; Luo, Y.Q.; Li, Q.; Njolibimi, M.; Li, W.J.; Hong, B. A high-permeability method for extracting purple yam saponins based on ultrasonic-assisted natural deep eutectic solvent. Food Chem. 2024, 457, 140046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, I.; Sousa, A.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R.; Bento, A.; Estevinho, L.; Pereira, J.A. Total phenols, antioxidant potential and antimicrobial activity of walnut (Juglans regia L.) green husks. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2008, 46, 2326–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ZamaniBahramabadi, E.; Afshar, H.M.; Rezanejad, F. Chemical constituents of green peel of Persian walnut (Juglans regia L.) fruit. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2024, 14, 27519–27524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadaş, F.; Gültepe, N. Effects of walnut (Juglans regia) green peel extract on growth performance and challenge to enteric redmouth disease (Yersinia ruckeri) in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Isr. J. Aquac. Bamidgeh 2025, 77, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, C.D.; Santos, T.B.; Freitas, R.H.C.N.; Pacheco, P.A.F.; da Rocha, D.R. Juglone: A versatile natural platform for obtaining new bioactive compounds. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2021, 21, 2018–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liga, S.; Paul, C.; Peter, F. Flavonoids: Overview of biosynthesis, biological activity, and current extraction techniques. Plants 2023, 12, 2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoye, C.O.; Jiang, H.F.; Wu, Y.F.; Li, X.; Gao, L.; Wang, Y.L.; Jiang, J.X. Bacterial biosynthesis of flavonoids: Overview, current biotechnology applications, challenges, and prospects. J. Cell. Physiol. 2024, 239, e31006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.T.; van Spronsen, J.; Witkamp, G.J.; Verpoorte, R.; Choi, Y.H. Natural deep eutectic solvents as new potential media for green technology. Anal. Chim. Acta 2013, 766, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.H.; Zhao, G.J.; Wu, G.D.; Bo, Y.K.; Yang, D.; Guo, J.J.; Ma, Y.; An, M. An ultrasound-assisted extraction using an alcohol-based hydrophilic natural deep eutectic solvent for the determination of five flavonoids from Platycladi cacumen. Microchem. J. 2024, 198, 110076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, R.; Wani, S.M.; Manzoor, S.; Masoodi, F.A.; Dar, M.M. Green extraction of bioactive compounds from apple pomace by ultrasound assisted natural deep eutectic solvent extraction: Optimisation, comparison and bioactivity. Food Chem. 2023, 398, 133871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meenu, M.; Bansal, V.; Rana, S.; Sharma, N.; Kumar, V.; Arora, V.; Garg, M. Deep eutectic solvents (DESs) and natural deep eutectic solvents (NADESs): Designer solvents for green extraction of anthocyanin. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2023, 34, 101168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roda, A.; Santos, F.; Chua, Y.Z.; Kumar, A.; Do, H.T.; Paiva, A.; Duarte, A.R.C.; Held, C. Unravelling the nature of citric acid: L-arginine: Water mixtures: The bifunctional role of water. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2021, 23, 1706–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.B.; Li, Q.; Hong, H.; Yang, S.; Zhang, R.; Wang, X.Q.; Jin, X.; Xiong, B.; Bai, S.C.; Zhi, C.Y. Lean-water hydrogel electrolyte for zinc ion batteries. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, K.A.; Sadeghi, R. Physicochemical properties of deep eutectic solvents: A review. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 360, 119524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manasi, I.; Bryant, S.J.; Hammond, O.S.; Edler, K.J. Interactions of water and amphiphiles with deep eutectic solvent nanostructures. In Eutectic Solvents and Stress in Plants; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; Volume 97, pp. 41–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhao, X.M.; Tang, S.Y.; Wu, K.J.; Wang, B.S. Structure–properties relationships of deep eutectic solvents formed between choline chloride and carboxylic acids: Experimental and computational study. J. Mol. Struct. 2023, 1273, 134283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, I.; Dar, A.H.; Dash, K.K.; Pandey, V.K.; Fayaz, U.; Shams, R.; Srivastava, S.; Singh, R. Deep eutectic solvents for extraction of functional components from plant-based products: A promising approach. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2023, 33, 101102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinho, M.R.; Lima, A.S.; Oliveira, G.D.R.; Liao, L.M.; Franceschi, E.; da Silva, R.; Cardozo, L. Choline chloride- and organic acids-based deep eutectic solvents: Exploring chemical and thermophysical properties. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2024, 69, 3403–3414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusof, R.; Abdulmalek, E.; Sirat, K.; Rahman, M.B.A. Tetrabutylammonium bromide (TBABr)-based deep eutectic solvents (DESs) and their physical properties. Molecules 2014, 19, 8011–8026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciel, E.N.; Almeida, S.K.C.; da Silva, S.C.; de Souza, G.L.C. Examining the reaction between antioxidant compounds and 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) through a computational investigation. J. Mol. Model. 2018, 24, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munteanu, I.G.; Apetrei, C. Analytical methods used in determining antioxidant activity: A review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, J.; Liu, Y.M.; Li, J.; Lu, Z.Y.; Yang, W.S. Phenanthroline method for quantitative determination of surface carboxyl groups on carboxylated polystyrene particles with high sensitivity. Surf. Interface Anal. 2009, 41, 577–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedair, H.M.; Samir, T.M.; Mansour, F.R. Antibacterial and antifungal activities of natural deep eutectic solvents. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 108, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Q.; Chen, J.X.; Tang, Y.L.; Wang, J.; Yang, Z. Assessing the toxicity and biodegradability of deep eutectic solvents. Chemosphere 2015, 132, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taysun, M.B.; Sert, E.; Atalay, F.S. Effect of hydrogen bond donor on the physical properties of benzyltriethylammonium chloride based deep eutectic solvents and their usage in 2-ethyl-hexyl acetate synthesis as a catalyst. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2017, 62, 1173–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.M.; Silva, E.; Reis, R.L.; Duarte, A.R.C. A closer look in the antimicrobial properties of deep eutectic solvents based on fatty acids. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2019, 14, 100192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, G.M.; Townley, G.G.; Martínez-Espinosa, R.M. Controversy on the toxic nature of deep eutectic solvents and their potential contribution to environmental pollution. Heliyon 2022, 8, e12567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thinh, B.B.; Thin, D.B.; Ogunwande, I.A. Chemical composition, antimicrobial and antioxidant properties of essential oil from the leaves of Vernonia volkameriifolia DC. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2024, 19, 1934578X241239477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oke, E.A.; Ijardar, S.P. Advances in the application of deep eutectic solvents based aqueous biphasic systems: An up-to-date review. Biochem. Eng. J. 2021, 176, 108211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.F.; Liu, C.L.; Luo, Y.; Shi, H.N.; Li, Q.; PinChu, C.E.; Li, X.J.; Yang, J.L.; Fan, W. Oxalate in plants: Metabolism, function, regulation, and application. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2022, 70, 16037–16049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atilhan, M.; Costa, L.T.; Aparicio, S. On the behaviour of aqueous solutions of deep eutectic solvents at lipid biomembranes. J. Mol. Liq. 2017, 247, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanisz, M.; Stanisz, B.J.; Cielecka-Piontek, J. A comprehensive review on deep eutectic solvents: Their current status and potential for extracting active compounds from adaptogenic plants. Molecules 2024, 29, 4767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.Y.; Wang, B.R.; Han, S.Y.; Zhang, Y.H.; Mu, Z.S. Extraction of hydroxy safflower yellow A and anhydroxysafflor yellow B from safflower florets using natural deep eutectic solvents: Optimization, biological activity and molecular docking. Food Biosci. 2025, 68, 106418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Pei, F.X.; Huang, J.J.; Li, G.Z.; Zhong, C.L. Application of deep eutectic solvents on extraction of flavonoids. J. Sep. Sci. 2024, 47, 2300925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.N.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.P.; Liu, W. Application of deep eutectic solvents in food analysis: A review. Molecules 2019, 24, 4594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airouyuwa, J.O.; Mostafa, H.; Ranasinghe, M.; Maqsood, S. Influence of physicochemical properties of carboxylic acid-based natural deep eutectic solvents (CA-NADES) on extraction and stability of bioactive compounds from date (Phoenix dactylifera L.) seeds: An innovative and sustainable extraction technique. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 388, 122767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogihara, W.; Aoyama, T.; Ohno, H. Polarity measurement for ionic liquids containing dissociable protons. Chem. Lett. 2004, 33, 1414–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarikurkcu, C.; Kirkan, B.; Ozer, M.S.; Ceylan, O.; Atilgan, N.; Cengiz, M.; Tepe, B. Chemical characterization and biological activity of onosma gigantea extracts. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2018, 115, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, M.Z.; Fu, X.Q.; Deng, L.; Li, Z.L.; Dang, Y.Y. Phenolic extraction from grape (Vitis vinifera) seed via enzyme and microwave co-assisted salting-out extraction. Food Biosci. 2021, 40, 100919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papuc, C.; Crivineanu, M.; Goran, G.; Nicorescu, V.; Durdun, N. Free radicals scavenging and antioxidant activity of European Mistletoe (Viscum album) and European Birthwort (Aristolochia clematitis). Rev. Chim. 2010, 61, 619–622. [Google Scholar]

- Dlugosz, O.; Chmielowiec-Korzeniowska, A.; Drabik, A.; Tymczyna, L.; Banach, M. Bioactive selenium nanoparticles synthesized from propolis extract and quercetin based on natural deep eutectic solvents (NDES). J. Clust. Sci. 2023, 34, 1401–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.T.; Varypataki, E.M.; Golovina, E.A.; Jiskoot, W.; Witkamp, G.J.; Choi, Y.H.; Verpoorte, R. Natural deep eutectic solvents in plants and plant cells: In vitro evidence for their possible functions. In Eutectic Solvents and Stress in Plants; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; Volume 97, pp. 159–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.W.; Wang, D.D.; Fang, J.X.; Song, Z.X.; Geng, J.M.; Zhao, J.F.; Fang, Y.F.; Wang, C.T.; Li, M. Green and efficient extraction of flavonoids from Perilla frutescens (L.) britt. Leaves based on natural deep eutectic solvents: Process optimization, component identification, and biological activity. Food Chem. 2024, 452, 139508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| CADESs | Water Content (wt%) | Conductivity | Polarity | π* | β | α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (μs·cm−1) | (kcal·mol−1) | |||||

| CADES-1 | 4.4 ± 0.08 | 4880 ± 1.63 | 48.2 | 1.014 | 0.621 | 1.283 |

| CADES-2 | 1.5 ± 0.08 | 2110 ± 2.45 | 47.8 | 1.100 | 0.525 | 1.334 |

| CADES-3 | 2.1 ± 0.08 | 965 ± 0.82 | 48.6 | 1.268 | 0.336 | 0.979 |

| CADES-4 | 7.3 ± 0.08 | 1986 ± 1.25 | 48.1 | 1.057 | 0.597 | 1.076 |

| CADES-5 | 8.4 ± 0.08 | 15,930 ± 4.18 | 48.1 | 1.057 | 0.573 | 1.131 |

| CADES-6 | 1.3 ± 0.08 | 67 ± 0.12 | 93.4 | 1.472 | 0.359 | 1.027 |

| CADES-7 | 19.2 ± 0.12 | 21,300 ± 3.37 | 92.2 | 1.552 | 1.235 | 2.034 |

| CADES-8 | 5.0 ± 0.05 | 281 ± 1.25 | 48.1 | 1.100 | 0.598 | 1.264 |

| CADES-9 | 7.4 ± 0.05 | 4.79 ± 0.09 | 79.9 | 1.309 | 0.458 | 1.338 |

| CADES-10 | 2.5 ± 0.05 | 1410 ± 0.82 | 47.9 | 1.100 | 0.549 | 1.299 |

| CADESs | DPPH (μmol TE/mL) | ABTS (μmol TE/mL) | Fe2+ (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CADES-1 | 198.9 ± 6.82 | 28.0 ± 7.55 | 13.2 ± 3.20 |

| CADES-2 | 200.8 ± 6.62 | 31.8 ± 2.19 | 98.9 ± 0.48 |

| CADES-3 | 198.7 ± 2.07 | 60.4 ± 4.77 | 49.6 ± 3.04 |

| CADES-4 | 196.4 ± 1.45 | 70.0 ± 6.16 | 85.1 ± 0.66 |

| CADES-5 | 197.3 ± 4.14 | 13.1 ± 6.76 | 87.9 ± 0.12 |

| CADES-6 * | 110.4 ± 1.65 | 32.6 ± 2.58 | 8.3 ± 0.50 |

| CADES-7 * | 176.2 ± 0.83 | 29.4 ± 2.19 | 96.2 ± 2.04 |

| CADES-8 * | 113.7 ± 0.21 | 38.2 ± 3.78 | 8.4 ± 1.33 |

| CADES-9 * | 95.9 ± 4.34 | 27.4 ± 2.98 | 7.1 ± 1.18 |

| CADES-10 * | 79.0 ± 1.65 | 19.1 ± 1.79 | 2.9 ± 1.04 |

| CADESs | E. coli | P. aeruginosa | S. aureus | E. faecalis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CADES-1 | 7.5 | 3.75 | 7.5 | 7.5 |

| CADES-2 | 7.5 | 7.5 | 15 | 7.5 |

| CADES-3 | 7.5 | 7.5 | 15 | 15 |

| CADES-4 | 30 | 30 | 15 | 30 |

| CADES-5 | 3.75 | 3.75 | 3.75 | 3.75 |

| CADES-6 | 15 | 7.5 | 30 | 30 |

| CADES-7 | 7.5 | 7.5 | 7.5 | 7.5 |

| CADES-8 | 30 | 15 | 15 | 15 |

| CADES-9 | 15 | 7.5 | 7.5 | 15 |

| CADES-10 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 |

| Solvents | Dilution Factor | Number of Days (Bud Length: mm) | RGP % | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Day | 2 Days | 3 Days | 4 Days | |||

| Deionized water | / | 6.5 ± 0.12 | 21.8 ± 0.61 | 27.1 ± 0.45 | 41.5 ± 1.22 | 100 |

| CADES-1 | 400 | 1.4 ± 0.21 | 9.4 ± 0.12 | 13.1 ± 0.29 | 14.6 ± 1.10 | 60 |

| 1200 | 5.0 ± 0.49 | 25.5 ± 0.45 | 33.5 ± 0.86 | 35.2 ± 0.45 | 90 | |

| 2000 | 2.7 ± 0.29 | 15.8 ± 0.37 | 30.6 ± 1.14 | 29.7 ± 1.27 | 100 | |

| CADES-2 | 400 | 3.6 ± 0.37 | 13.5 ± 0.21 | 20.9 ± 0.61 | 22.7 ± 0.53 | 100 |

| 1200 | 7.4 ± 0.24 | 23.5 ± 0.53 | 35.7 ± 0.33 | 37.6 ± 0.69 | 90 | |

| 2000 | 2.3 ± 0.53 | 17.7 ± 0.58 | 31.5 ± 0.78 | 34.2 ± 0.57 | 100 | |

| CADES-3 | 400 | 1.9 ± 0.29 | 3.2 ± 0.21 | 3.8 ± 0.61 | 3.4 ± 0.37 | 100 |

| 1200 | 4.9 ± 0.16 | 11.5 ± 0.57 | 15.5 ± 1.18 | 23.7 ± 0.49 | 100 | |

| 2000 | 7.1 ± 0.49 | 22.1 ± 0.45 | 35.8 ± 0.78 | 60.0 ± 0.94 | 100 | |

| CADES-4 | 400 | 6.2 ± 0.05 | 13.6 ± 0.33 | 19.8 ± 0.41 | 31.1 ± 0.90 | 100 |

| 1200 | 7.7 ± 0.08 | 23.4 ± 0.57 | 40.3 ± 1.31 | 52.0 ± 1.63 | 100 | |

| 2000 | 9.4 ± 0.21 | 28.1 ± 0.49 | 45.8 ± 1.10 | 65.6 ± 1.06 | 100 | |

| CADES-5 | 400 | 2.6 ± 0.37 | 3.4 ± 0.24 | 7.2 ± 0.33 | 7.8 ± 0.53 | 100 |

| 1200 | 8.9 ± 0.12 | 20.3 ± 0.33 | 35.7 ± 0.94 | 54.8 ± 1.27 | 100 | |

| 2000 | 7.5 ± 0.05 | 23.8 ± 0.08 | 62.4 ± 1.27 | 74.3 ± 1.84 | 100 | |

| CADES-6 | 400 | 7.8 ± 0.53 | 19.1 ± 0.41 | 25.4 ± 0.69 | 25.6 ± 1.59 | 100 |

| 1200 | 8.2 ± 0.16 | 24.3 ± 0.29 | 31.5 ± 0.61 | 32.3 ± 1.06 | 100 | |

| 2000 | 10.6 ± 0.41 | 26.2 ± 0.37 | 36.1 ± 1.51 | 40.2 ± 0.61 | 100 | |

| CADES-7 | 400 | 0.0 ± 0.00 | 0.3 ± 0.05 | 0.3 ± 0.12 | 0.3 ± 0.05 | 20 |

| 1200 | 2.7 ± 0.24 | 7.7 ± 0.29 | 12.3 ± 0.53 | 12.8 ± 1.02 | 100 | |

| 2000 | 7.8 ± 0.45 | 28.3 ± 0.53 | 40.3 ± 0.98 | 41.5 ± 1.43 | 100 | |

| CADES-8 | 400 | 1.8 ± 0.12 | 2.8 ± 0.16 | 3.4 ± 0.21 | 3.4 ± 0.37 | 100 |

| 1200 | 4.0 ± 0.29 | 12.3 ± 0.16 | 23.3 ± 0.86 | 33.3 ± 0.73 | 100 | |

| 2000 | 5.9 ± 0.16 | 15.4 ± 0.45 | 33.8 ± 1.06 | 57.7 ± 1.22 | 100 | |

| CADES-9 | 400 | 4.5 ± 0.33 | 12.4 ± 0.49 | 17.3 ± 1.43 | 19.9 ± 1.18 | 100 |

| 1200 | 4.7 ± 0.45 | 16.4 ± 0.21 | 25.9 ± 1.59 | 42.1 ± 1.47 | 100 | |

| 2000 | 7.1 ± 0.33 | 26.3 ± 0.49 | 52.2 ± 1.67 | 69.0 ± 1.18 | 100 | |

| CADES-10 | 400 | 3.3 ± 0.69 | 6.0 ± 0.24 | 9.6 ± 0.65 | 12.8 ± 0.69 | 100 |

| 1200 | 9.1 ± 0.37 | 22.4 ± 0.29 | 51.9 ± 0.9 | 71.1 ± 1.71 | 100 | |

| 2000 | 8.3 ± 0.08 | 27.8 ± 0.42 | 49.5 ± 1.10 | 76.2 ± 1.14 | 100 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gong, L.; Yue, L.; Li, M.; Chen, Q.; Liu, X.; Gao, D.; Ren, J.; Zhang, N.; Zhu, J. Natural Carboxylic Acid Deep Eutectic Solvents: Properties, Bioactivities and Walnut Green Peel Flavonoid Extraction. Processes 2025, 13, 3763. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123763

Gong L, Yue L, Li M, Chen Q, Liu X, Gao D, Ren J, Zhang N, Zhu J. Natural Carboxylic Acid Deep Eutectic Solvents: Properties, Bioactivities and Walnut Green Peel Flavonoid Extraction. Processes. 2025; 13(12):3763. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123763

Chicago/Turabian StyleGong, Lei, Lili Yue, Menghao Li, Qilong Chen, Xuan Liu, Daming Gao, Junli Ren, Nan Zhang, and Jie Zhu. 2025. "Natural Carboxylic Acid Deep Eutectic Solvents: Properties, Bioactivities and Walnut Green Peel Flavonoid Extraction" Processes 13, no. 12: 3763. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123763

APA StyleGong, L., Yue, L., Li, M., Chen, Q., Liu, X., Gao, D., Ren, J., Zhang, N., & Zhu, J. (2025). Natural Carboxylic Acid Deep Eutectic Solvents: Properties, Bioactivities and Walnut Green Peel Flavonoid Extraction. Processes, 13(12), 3763. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123763