1. Introduction

Gold nanoparticles (GNPs) have a long and fascinating history that predates the scientific understanding of nanotechnology. Their unique optical properties have been exploited for centuries, often unknowingly, in art and craftsmanship. One of the earliest examples is the Lycurgus Cup from 4th-century AD Rome, which exhibits dichroic properties, appearing green in reflected light and deep red in transmitted light due to gold and silver NPs embedded in its glass matrix [

1]. Similarly, during the medieval period, colloidal gold was used to produce the vibrant red and purple hues of stained-glass windows in European cathedrals. These ancient artisans, while unaware of the nanoscale phenomena at play, empirically utilized gold’s ability to generate size-dependent colors [

2]. The first scientific account of colloidal gold came in the 17th century, when Andreas Cassius described the preparation of “Purple of Cassius,” a gold–tin chloride complex that produced a deep purple coloration in ceramics and glass. A major milestone was achieved by Michael Faraday in 1857, who prepared stable colloidal gold solutions and recognized that their ruby-red color differed fundamentally from bulk gold. Faraday attributed this to the small size of gold particles and their interaction with light phenomena now understood as localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) [

3]. With the advent of electron microscopy in the mid-20th century, scientists were able to directly observe GNPs, paving the way for their application in biology. Immunogold labeling, where GNPs conjugated to antibodies are used as markers in electron microscopy, became a key technique for visualizing cellular structures. In recent decades, the development of nanotechnology has transformed GNPs into versatile tools across disciplines. Their biocompatibility, tunable size and shape, and ease of surface functionalization have led to applications in drug delivery [

4,

5], diagnostics [

6], photothermal therapy [

7], catalysis [

8], environmental sensing [

9], and advanced materials [

10]. GNPs continue to play a central role in nanomedicine and materials science, making them one of the most important and well-studied nanomaterials in contemporary research.

GNPs used for drug delivery are synthesized through various methods employing different chemical reagents, with the chemical reduction method being the most versatile and widely used. Synthesis of GNPs via the chemical reduction method follows the simple Turkevich method [

11,

12] in the aqueous phase and proceeds to the complex Brust–Schiffrin method [

13] and Oleylamine method [

14] in the organic phase. The reagents used in the modified methods often use a variety of chemicals. Sodium borohydride causes reproductive or developmental harm [

15], cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) is highly toxic to cells at sub-micromolar concentrations, toxic to aquatic life, and may cause organ damage through repeated exposure [

16], while oleylamine may cause damage to the liver, gastrointestinal tract, and immune system [

17].

Hence, the safer green synthesis methods are gaining attention as they offer safer, cheaper, and as environmentally sustainable alternatives. Chitosan [CS] is a natural polysaccharide and is widely used in the pharmaceutical industries, as well as the food industries, due to its high biocompatibility and biodegradability with low toxicity [

18,

19]. Commercially, the bioactive polymer CS is synthesized through the deacetylation process of chitin, which is collected from the outer skeleton of crab, shrimp, lobster, and crayfish shells [

20]. Structurally, CS is a cationic biopolymer consisting of D-glucosamine and N-acetyl D-glucosamine units attached by β-1,4 glycosidic bonds. Biopolymer CS has two types of bioactive functional groups, the hydroxyl group and the amino group, and these active groups are responsible for the potential antimicrobial activity of CS [

20,

21]. CS is a positively charged molecule due to the presence of –NH3

+ groups, and these active amino groups are also responsible for the interaction with the negatively charged cell membranes of bacteria [

21,

22]. While CS is commonly used in drug delivery applications, it is also used as a stabilizing agent for the synthesis of different metallic nanoparticles. It can facilitate the modification of the surface physical absorption and electrostatic interaction, thus improve the stability and bioactivity of nanoparticles and making them perfect candidates as potential therapeutic agents [

23,

24,

25,

26]. Meanwhile, reduction using trisodium citrate is versatile and a safer option in the preparation of negatively charged GNPs. CS and TSC serve a dual purpose, in that they reduce Au

+3 to Au

0 and stabilize the GNPs by imparting strong positive and negative surface charges. Despite the understanding gained to date of the reducing and stabilizing mechanism, the process parameters significantly affect the synthesis of GNPs, which needs to be studied.

In this study, the process parameters for the synthesis of CS-functionalized gold nanoparticles was investigated through a fractional factorial design. A 26−2 fractional factorial design was utilized to screen process parameters affecting the size and polydispersity of the GNPs. Two different types of GNPs were prepared based on the surface charge and applicability. Positively charged gold nanoparticles were prepared using chitosan as the reducing agent, while trisodium citrate was used to prepare negatively charged GNPs. This study aimed to explore the roles of the reducing agent, concentration of reducing agent, pH, reducing temperature, agitation speed, and agitation time in the synthesis of positively charged and negatively charged GNPs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Chitosan (low MW) extra pure, 10–150 m·Pas, 90% DA; gold chloride trihydrate (tetrachloroauric acid (HAuCl4)); and sodium citrate tribasic dihydrate extra pure, 98% were procured from Sisco Research Laboratories Pvt. Ltd., Mumbai, Maharashtra, India. Glacial acetic acid, nitric acid, and hydrochloric acid were procured from Actylis, Vasna Chacharavadi, Gujarat, India. Ultrapurified water was produced from a Milli-Q water assembly (DirectQ-8, Merck, Cambridge, MA, USA) with a resistivity of 18.2 MΩ·cm. Ultrapurified water was utilized in the preparation of all reactions. All other chemicals and reagents were used at analytical grade. All chemicals were procured from reputed suppliers and used without any further purification.

2.2. Software and Instrumentation

Design Expert® 13.0.1 (Trial Version, Stat-Ease, Minneapolis, MN, USA) was used for plotting the fractional factorial design. A UV Spectrophotometer-1900 (Shimadzu, Tokyo, Japan) was used for a surface plasmon resonance effect, and a Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZS (Malvern Panalytical Ltd., Malvern, UK) was used for the hydrodynamic particle size, polydispersity index, and zeta potential. A Milli-Q assembly was used to produce ultrapure water.

2.3. Fractional Factorial Experimental Design

Fractional factorial designs are one the most widely used for screening purposes, as they enable the evaluation of a large number of input factors with a reduced number of experiments required [

27,

28]. The fractional factorial design (FFD) was employed to systematically screen and identify the significant process parameters affecting the synthesis of CS-functionalized GNPs. A 2

k−p fractional factorial design was chosen, where k represents the number of factors studied and p denotes the fraction of the full factorial matrix. A 2

6−2 fractional factorial design was employed to identify the critical process parameters influencing the synthesis of GNPs. This statistical design enables the efficient evaluation of the main effects and selected interaction effects of multiple factors using a reduced number of experimental runs, compared to a full factorial design. In this study, six independent variables—(X1) type of reducing agent, (X2) concentration of reducing agent, (X3) reaction temperature, (X4) pH of the reaction medium, (X5) stirring speed, and (X6) stirring time—were screened at two levels (high and low). The main effect of these factors was studied on one important formulation attribute, i.e., particle size (PS) or polydispersity index (PDI). A 2

6−2 design (one-quarter fraction) was selected, resulting in 16 experimental runs. The experimental matrix was generated using Design Expert

® Software (Trial Version 13, Stat-Ease Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA), and the runs were randomized to minimize systematic errors. Randomization may increase setup costs and experimental complexity, but it is indispensable for ensuring that observed effects truly represent the underlying processes being studied rather than experimental artifacts, thereby maintaining the integrity and reliability of the fractional factorial screening experiment [

29]. Independent and dependent variables for the fractional factorial design are shown in

Table 1.

Table 2 shows the fractional factorial design matrix with coded values, where X1 is a categorical factor and the rest are numeric factors.

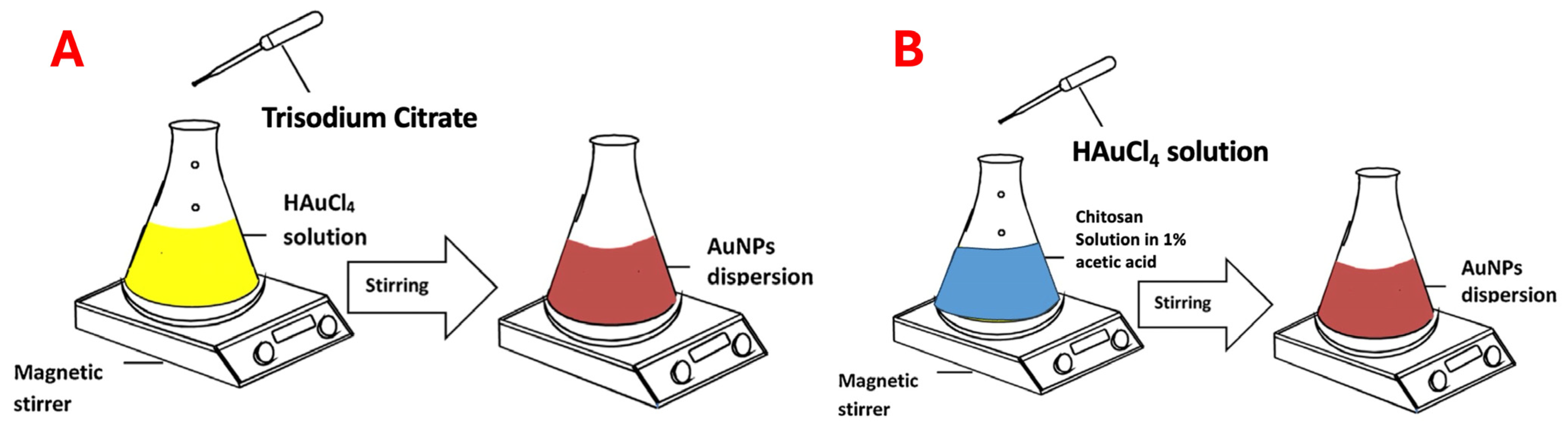

2.4. Preparation of Citrate-Capped (Cit-GNP) and Chitosan-Capped (CS-GNP) Gold Nanoparticles

All glassware used for this study was washed with freshly prepared Aqua Regia solution (HNO

3:HCl:: 1:3). For the preparation of GNPs, chemical reduction of HAuCl

4 was used in both methods.

Citrate-capped GNPs: The modified Turkevich method was employed as reported [

12]; in brief, 20 mL of ultrapurified water was poured into a 50 mL conical flask, and 1 mL of 10 mM HAuCl

4 solution was added. The pH of the solution was adjusted using 0.1% HCl or 0.1% NaOH. The flask was heated to 90 °C using a hot plate with a magnetic stirrer (REMI 2MLH, Mumbai, India). The conical flask was kept closed to keep the reaction volume constant. This reaction mixture was kept at 800 rpm. To this, 1 mL of 1% trisodium citrate solution was added dropwise to ensure the maximum homogeneity. The reaction mixture turned from pale yellow to a red wine color; this was an indication of the synthesis of GNPs. The prepared mixture was further stirred for 15 min and cooled down to room temperature. The prepared GNPs were stored in the refrigerator at 4 °C for further use.

Chitosan-capped GNPs: CS solution was prepared using low-molecular-weight CS. We prepared 0.2% CS solution in 1% glacial acetic acid, and 20 mL of CS solution was taken. The pH of the solution was adjusted using 0.1% HCl or 0.1% NaOH. This CS solution was heated using a hot plate with a magnetic stirrer (REMI 2MLH, Mumbai, India) to 90 °C. The volume was kept constant, and conical flasks were covered with aluminum foil. We added 1 mL of 10 mM solution of chloric acid rapidly to this solution, and the reaction mixture turned a dark blue color and eventually a wine red color; this indicated the synthesis of GNPs. The dispersion was stored at 4 °C in a refrigerator for further use.

Figure 1 shows the schematic diagrams of citrate-capped GNPs (A) and CS-capped GNPs (B).

2.5. Local Surface Plasmon Resonance Effect

The LSPR effect of GNPs was evaluated using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (UV−1900, Shimadzu, Tokyo, Japan). The GNP suspension was diluted 10-fold using ultrapure water to minimize scattering effects and bring the absorbance within the optimal measurement range of the instrument. The diluted GNP sample was placed in a clean quartz cuvette (1 cm path length), and the absorbance spectrum was recorded from 800 to 200 nm using a UV spectrophotometer (UV−1900, Shimadzu, Tokyo, Japan) with baseline correction against ultrapure water, to analyze the LSPR peak position and shape.

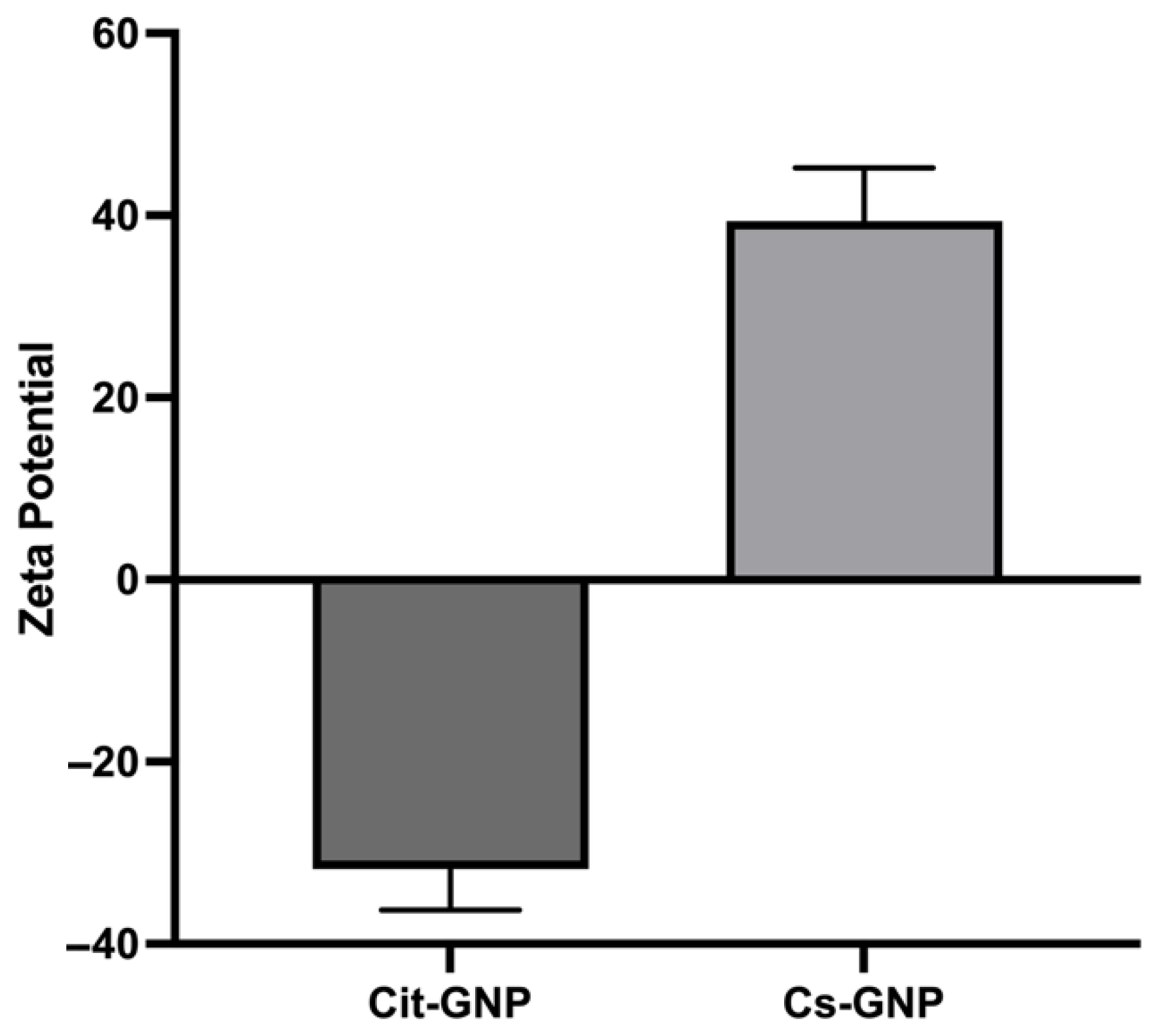

2.6. Particle Size, Zeta Potential, and Polydispersity Index

The hydrodynamic particle size, PDI, and zeta potential [

30] of the Cit-GNPs and CS-GNPs were determined using a Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZS (Malvern Panalytical Ltd., Malvern, UK) based on dynamic light scattering (DLS) and electrophoretic light scattering (ELS) principles as reported [

31] The GNP suspension was diluted 10-fold with ultrapure water to avoid multiple scattering effects and ensure the optimal sample concentration. Measurements were performed at 25 °C in a disposable polystyrene cuvette (for size and PDI) and in a folded capillary cell (for ZP). During the analysis, the GNP concentration was maintained, and the instrument’s count rate (kcps) was maintained above 350 kcps to achieve better accuracy and reliable results. Each measurement was carried out in triplicate, and the results were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation.

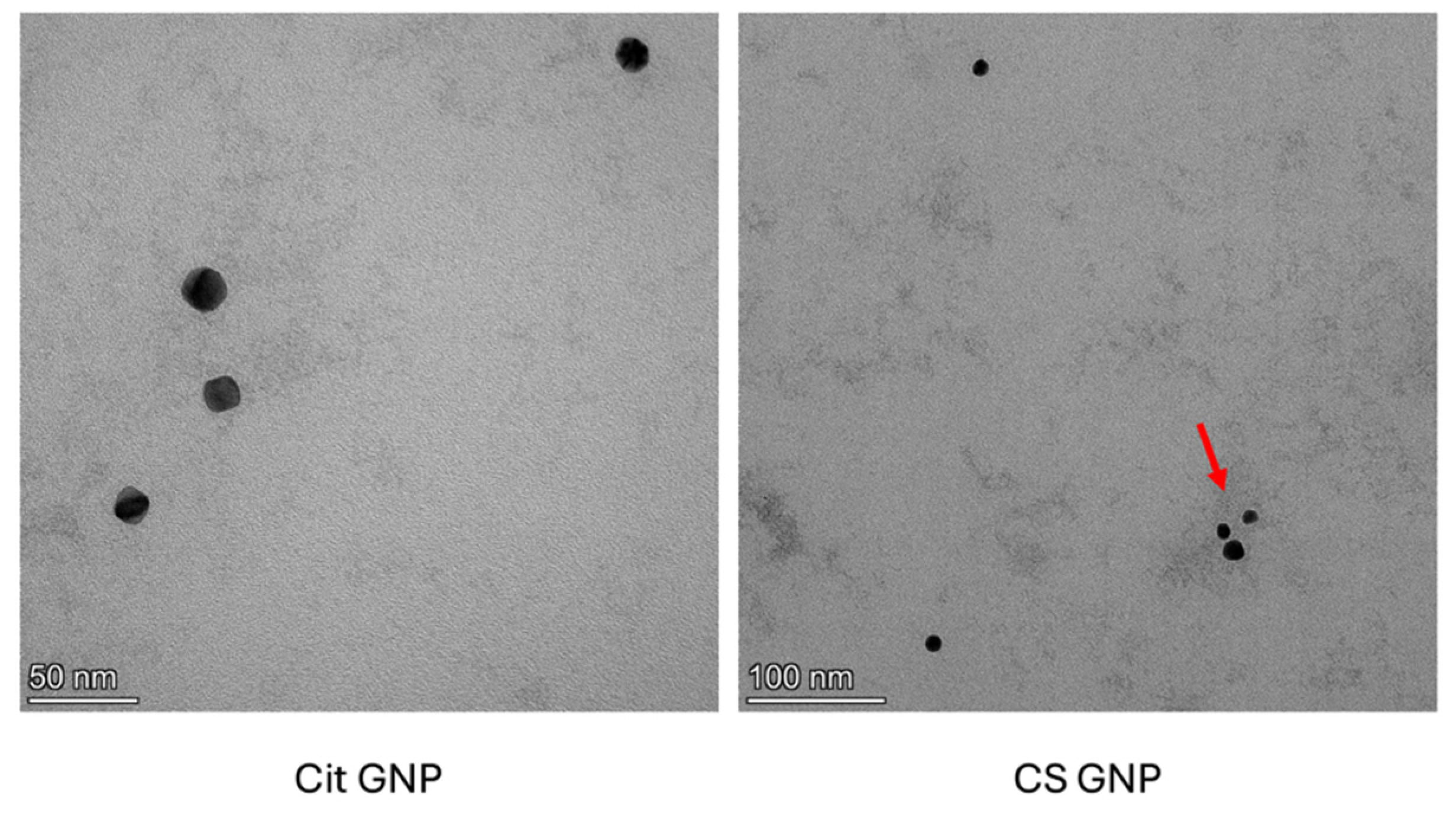

2.7. Transmission Electron Microscopy

The morphology of Cit-GNPs and CS-GNPs was observed using high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (FEI, Tecnai G2, F30, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) [

32]. Both dispersions were diluted 10 times with ultrapurified water, and drops of Cit-GNP and CS-GNP dispersions were placed on a carbon-coated copper grid stained with a 0.5% aqueous solution of phosphotungstic acid. This was directly positioned, then air-dried, prior to being imaged using a 300 keV acceleration voltage. Using different combinations of bright-field imaging at an increasing magnification up to 40,000×, the morphology and size of the GNPs were observed.

2.8. Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy

The Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectra of the samples were recorded to confirm the presence of chitosan on the surfaces of CS-GNPs. The analysis was performed using a Fourier-transform infrared spectrophotometer (IRSpirit, Shimadzu, Tokyo, Japan) in the range of 4000–400 cm−1. Samples were directly placed on the ATR crystal, and spectra were recorded at a resolution of 4 cm−1 with 32 scans per sample.

2.9. Gold Quantification by Inductively Coupled Plasma–Optical Emission Spectrometer

Gold quantification was performed using an inductively coupled plasma–optical emission spectrometer (Avio 200 ICP-OES, Perkin Elmer, Hopkinton, MA, USA). The ICP-OES system employed a simultaneous optical emission detection system with high-resolution capabilities suitable for trace metal analysis. Both the samples were digested in aqua regia (HCl:HNO

3, 3:1

v/

v), diluted with ultrapure water, and analyzed against a calibration curve prepared from gold standards (LOD: 0.031 µg/mL, R

2 > 0.999). Optimized instrumental parameters are presented in

Table 3.

2.10. Biocompatibility of Gold Nanoparticles

The biocompatibility of Cit-GNPs and CS-GNPs was tested against HaCaT and CaCO-2 cells as reported [

31,

33]. Briefly, the cells were cultured in high-glucose medium (Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium—DMEM), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and penicillin–streptomycin (pen/strep-5000 U/mL). The cells (HaCaT and CaCO-2) were separately seeded at a density of 1 × 10

4 cells/well in a 96-well plate and incubated at 37 °C under a 5% CO

2 (5%) atmosphere until a confluence of 80% was reached. The cells were individually treated with Cit-GNPs and CS-GNPs at varied concentrations (3.12 μg/mL to 100 μg/mL), while the CS was tested at 100 μg/mL, and we compared the viability against untreated cells. The viability was analyzed using an MTT assay at 560 nm using a microplate reader, and the background was subtracted with the measured OD at 670 nm.

2.11. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were conducted in triplicate and repeated in two independent studies to ensure their reliability. The collected data were analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Dunn’s test to determine significant differences between groups. A significance threshold of p < 0.05 was applied throughout this study to assess statistical significance.

5. Conclusions

In this study, a 26−2 fractional factorial design (FFD) was successfully employed to screen and identify the critical process parameters influencing the synthesis of gold nanoparticles (GNPs) using CS and trisodium citrate as reducing and stabilizing agents. The key objective was to understand how six independent variables—type of reducing agent, its concentration, reaction temperature, pH, stirring speed, and stirring time—affect the particle size and polydispersity index (PDI) of the synthesized GNPs. The statistical analysis revealed that pH was the most influential factor, significantly affecting both particle size and the PDI. A lower pH (3.5) favored the formation of smaller, more monodisperse nanoparticles, likely due to enhanced nucleation and faster reduction kinetics, while a higher pH (8.5) led to larger and more polydisperse particles. The type of reducing agent also played a significant role, with CS producing smaller and more uniform nanoparticles compared to trisodium citrate, attributed to its dual role in reduction and steric stabilization via its amino and hydroxyl groups. The concentration of reducing agent, though not significant for particle size, had a notable impact on the PDI, where higher concentrations resulted in narrower size distributions. Other factors such as temperature, stirring speed, and stirring time were found to have comparatively less significant individual effects, though some interactions, such as between reducing agent type, concentration, and stirring time, demonstrated a notable influence on nanoparticle uniformity. The UV-Vis spectra confirmed the presence of LSPR, with peak shifts correlating with the particle size and dispersity. Overall, the use of FFD provided a statistically robust and resource-efficient method for identifying significant formulation variables in gold nanoparticle synthesis. The findings highlight that careful control of pH and selection of a biocompatible reducing agent like CS are crucial for producing GNPs with an optimal size and stability. Moreover, the use of green synthesis via CS supports the ongoing push toward safer, more sustainable nanomaterial development. In conclusion, the integrated approach of factorial screening, physicochemical characterization, and green chemistry demonstrates a rational strategy for the controlled synthesis of gold nanoparticles with desired attributes, underscoring the critical interplay between formulation variables and nanoparticle properties.