Abstract

Background: Design workshops offer effective methods in eliciting end-user participation from design inception to completion. Workshops unite stakeholders in the utilization of participatory methods, coalescing in the best possible creative solutions. Objective: This systematic review aimed to identify design approaches whilst providing guidance to health information technology designers/researchers in devising and organizing workshops. Methods: A systematic literature search was conducted in five medical/library databases identifying 568 articles. The initial duplication removal resulted in 562 articles. A criteria-based screening of the title field, abstracts, and pre-full-texts reviews resulted in 72 records for full-text review. The final review resulted in 10 article exclusions. Results: 62 publications were included in the review. These studies focused on consumer facing and clinical health information technologies. The studied technologies involved both clinician and patients and encompassed an array of health conditions. Diverse workshop activities and deliverables were reported. Only seven publications reported workshop evaluation data. Discussion: This systematic review focused on workshops as a design and research activity in the health informatics domain. Our review revealed three themes: (1) There are a variety of ways of conducting design workshops; (2) Workshops are effective design and research approaches; (3) Various levels of workshop details were reported.

1. Introduction

Participatory approaches are common for designing user-centered health information technologies (HIT) [1,2,3]. Participatory approaches encourage including the tacit (and often invisible) knowledge of the users [4] by involving a wide variety of users to ensure all user needs are addressed in the design [5]. Design workshops can be an effective way of eliciting end-user participation by actively incorporating and translating valuable input from design inception to completion. A design workshop can be defined as a codesign environment opportunity for a team to cohesively disentangle a specified problem by undergoing a series of group exercises to either initiate or finalize a design, or to ameliorate an obstacle on an existing design. Workshops can be rewarding by bringing relevant stakeholders together to utilize powerful tools and techniques, culminating in the best possible creative solutions.

HIT Workshops can be utilized as a design or research activity. As a design activity, workshops often focus on solving a HIT design problem and support collaboration between designers and users. For example, a workshop can be organized to modify an existing HIT app (e.g., food tracking app) previously tailored to a specific population to be inclusive of additional populations. As a research activity, workshops can generate and delineate the necessary knowledge to improve the efficacy of a design process and outcome. For example, a workshop can examine the impact of artificial intelligence on clinical decision making by diverse types of clinicians.

Workshops can be particularly beneficial for the design of HIT targeting diverse end-users (clinicians, caregivers, patients), as the workshop atmosphere can cultivate the conception of a design that meets the needs of all users. As health care becomes increasingly distributed among clinical and daily living settings [6,7,8,9,10], the scope of HIT and its user panel have significantly broadened. Workshops can play a vital role in the redesign of current HIT to match the new scope and expanding user needs.

The benefits of a workshop are contingent on involving the correct selection of participants and utilizing the right tools and techniques for the targeted population. Moreover, conceptual frameworks are useful to keep the scope of workshop activities focused. The aim of this systematic review was to identify the tools, techniques, and approaches available. This information should provide guidance to HIT designers and researchers in devising and organizing design workshops. This guidance could help structure the coordination and delivery of a more efficient workshop targeting user-centered design practices. Furthermore, examining the strengths and weaknesses of previous workshop would serve as a lesson to design more novel workshops. For example, at the time of COVID-19 or a similar pandemic, workshops could be held remotely.

2. Methods

A systematic literature search was conducted by a health librarian in five databases (Medline, Embase, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and Web of Science) including the following keywords: Participant design, codesign, cooperative design, user involvement, stakeholder participation, health information technology, medical informatics, software, phone app, mHealth, digital health, games, gaming, gamify, telehealth, telemedicine, software design, universal design, computer-aided design, mobile applications, stakeholder, patients, health provider, physician, nurse, therapist, caregiver, user, and family. (Supplementary Material File S1 describes search strategies).

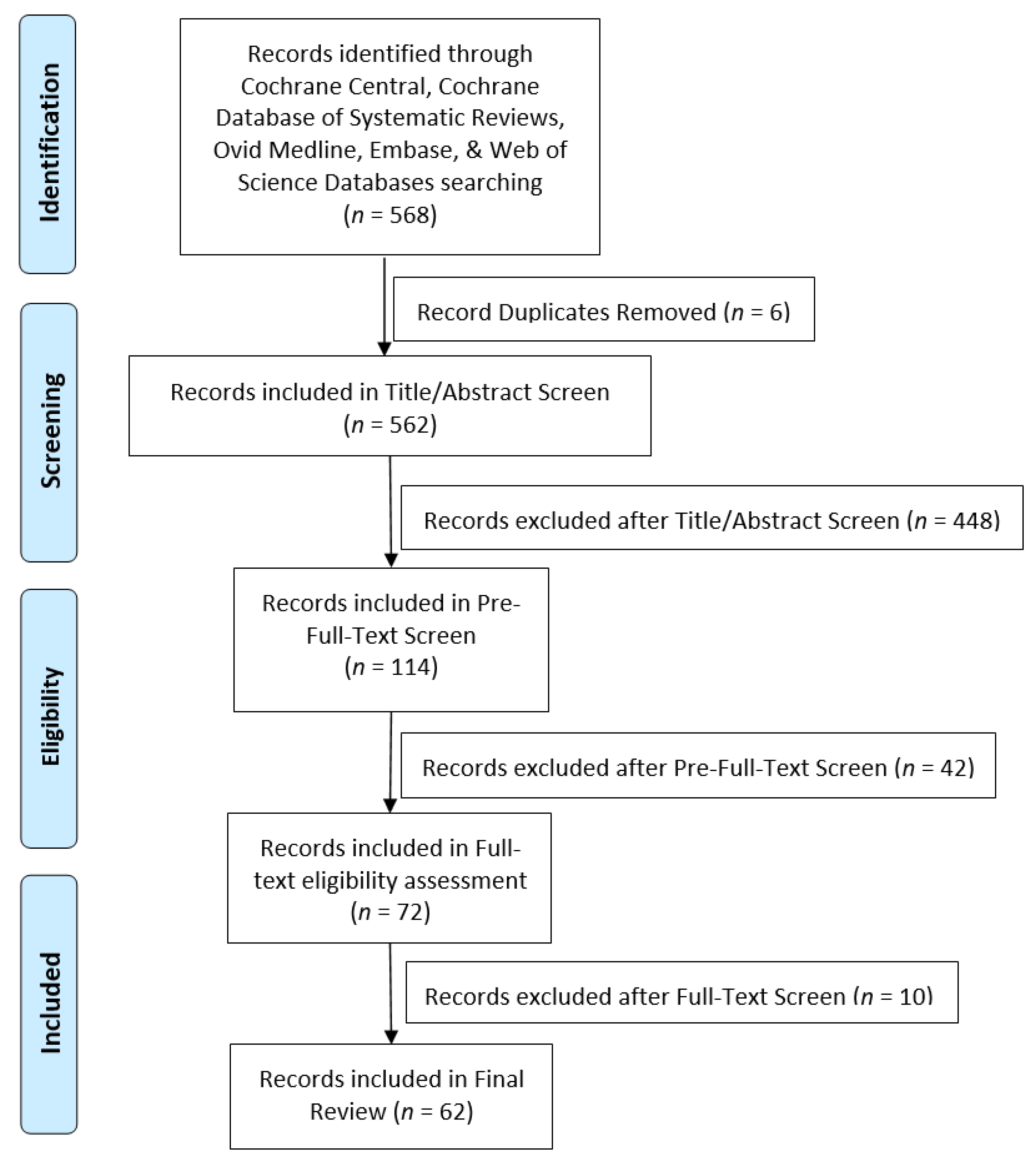

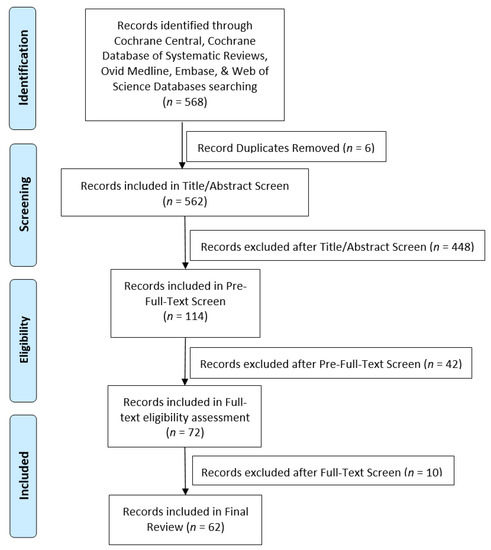

The search process identified a total of 568 articles, with 562 articles remaining after initial article duplication removal. Figure 1 shows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [11] diagram for the search methodology. The diagram outlines the number of records that were identified, included, and excluded.

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram for search methodology.

The second and third authors (C.M.S. and O.F.) conducted concurrent independent reviews of the title field by selecting articles that included participatory design (PD), co-design (CoD), and/or were related to HIT, reducing the number to 364 articles. The concurrent independent reviews continued for the reconciliation of abstracts and pre-full-text reviews (i.e., reviewing full text partially, focusing on only predetermined sections), applying inclusion/exclusion criteria, and resulting in 114 and 72 relevant records, respectively. Studies that met inclusion criteria were journal articles and conference papers explicitly mentioning PD or codesign sessions and workshops utilized in HIT. The first author (M.O.) mediated unreconciled article disputes following each screening cycle. A full-text review of 72 articles was completed by the second author (C.M.S.), followed by the extraction of the following elements from the included articles: year, title, author, journal, type of article, country, purpose, target technology, target disease/medical population or service, guiding framework, phases, participant selection, participant profiles, number of participants, workshop duration, number of workshops, activities and approach, tools and equipment, deliverables/results, evaluation, pre and post PD methods, issues reported/weaknesses, and strengths/benefits.

Studies that were excluded were those that mentioned PD sessions/workshops but did not explicitly describe the implementation process, those that were not focused on a health-related field/topic, and/or those that did not differentiate between PD methods. Abstracts without a full paper, posters, and duplicates were likewise excluded. The reconciliation of abstract reviews resulted in 250 excluded records, leaving 114 articles for pre-full-text review. The pre-full-text review resulted in excluding 42 articles, and an additional 10 articles were excluded in the full-text review. Sixty-two articles published from 2006 to 2020 met the inclusion criteria.

Publications that were included met the following criteria: (1) written in English, (2) author identified, (3) targeted medical/health-related technology, (4) followed a participatory approach to workshop or session design, (5) full-text available electronically, and (6) included participatory design interchangeable terms such as cocreation, codesign, and user-centered design. Eligible publications included records with varied stakeholders (e.g., clinicians, patients, caregivers), and involved adults and/or children participating in HIT PD. Final full-text inclusion articles ranged in publication date from 2006 to 2020. Additionally, studies that summarized a participatory process without clearly detailing the activities and/or actions were excluded.

3. Results

Sixty-two publications [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73] from the years 2006 to 2020 were included in the review. These publications are a result of 59 unique studies. Included publications were predominantly journals (n = 57), but conference papers were also included [36,55,60,63,71] (n = 5). Studies were conducted in six continents (Europe, 34; Oceania, ten; North America, eight; Asia, four; Africa, one; South America, one). Study location was not reported in four studies. Included studies focused on consumer-facing health technologies (e.g., app or website; n = 39), clinical health information technologies (e.g., electronic health records; n = 8), technologies that involve both clinicians and patients as users (e.g., telehealth technologies; n = 12) and other technologies (n = 3). The studies represented a wide variety of health conditions (e.g., mental health, heart failure, asthma, dementia, kidney transplantation), life span (e.g., youth, adult, elderly), and type of users (patients, caregivers, clinicians). Workshops could be accomplished as a single workshop (n = 10) or as a series (n = 52). The highest number of reported workshops in a single study was 20 [26]. Workshops could include homogeneous (e.g., only clinicians) or heterogenous (e.g., clinicians and patients) groups. The number of participants (in each workshop) varied from 4 [17,19,23] to 47 [52]. The duration of a workshop varied between one hour and over one day.

The included studies focused on a wide variety of target diseases, settings, treatments, or populations. In three of the studies, the target population consisted of clinicians and other stakeholders as users. In four of the studies, the target population focused on the caregivers of patients with various conditions. The remaining 55 studies focused on various conditions. Antibiotic management was the focus in three studies. Each of the following conditions was the focus in two included papers: Type I Diabetes, asthma, adolescent mental health, HIV, chronic illness (general), rheumatoid arthritis, heart disease, and mental health (general).

Many workshop activities and deliverables were reported. These activities include:

3.1. Discussion Activities

- Whole group or small group discussions (guided by semistructured questions or findings from previous steps)

- Brainstorming (using Post-it notes, poster size papers, flipcharts)

- Affinity diagrams

- Collecting ideas

- Sorting methods

- Idea notetaking on sticky Prioritization

- Exploring a selected technology

- Creating human scatter graph

- Note cards

3.2. Description of Experience

- Personas

- Vignettes on a ‘story-board’ in cartoon-strip format

- Case vignettes

- Scenarios

- Journey mapping

- Storytelling/storyboards

- Arranging pictures and labels describing the stages of before, during, and after a visit

- Talking on a specific experience

- Creating collages

- Creating instant visuals

3.3. Prototyping

- Developing mock-up models or prototypes

- Frame-by-frame sketches

- Solution sketch

- Presentation of mock-up, etc., by participants

- Rapid cycle iterative design

- Design sprints

3.4. Creating Conceptual Representations

- Concept mapping

- Responding to questions by creating a human scatter graph

- Creating an instant visual of the group’s perception and experience of mobile games and games for health

- Sketches of the participants’ design concepts

- Participant narrative representation of thoughts

3.5. Evaluation Activities

- Technology/product demonstrations

- Hands-on use of technology

- Debriefing

- Technology/prototype/idea/solution evaluation and providing feedback

- Workshop feedback

- Applications/apps

- Think Aloud

- Walkthrough exercise

- Questionnaires

3.6. Presentations

- Presentation of results of previous phases/literature, etc., by moderators

- Presentations or giving talk on a specific topic

3.7. Game Playing

- Design games

- Role-playing

3.8. Stimulate Group Participation

- Design cards

- Icebreaker session

- Field kit

- Prompt cards

- Presented substance images

- Lightning Demos activity

The grouping of workshop activities is not necessary mutually exclusive. Moreover, some of these activities may overlap. Primary deliverables of these workshops were:

- Prototypes/mock-up models (paper-based or wireframes)

- Research themes

- A list of recommendations/solutions/ideas

- Product/technology evaluation

Table 1 highlights the abstracted information from each study including authors, publication type, participants, activities, and deliverables.

Table 1.

Summary of Results of 62 publications.

Some workshops were performed as stand-alone design and research activities, while others included workshops as one part of a multiphase design and research process, encompassing other data collection methods such as interviews, focus groups, or observations. Workshops included in a multiphase project utilized preceding activity outcomes to preface the current workshop. Likewise, following an iterative process, workshops provided input to guide subsequent design activities, unless the design workshop was the concluding activity.

Some workshops were guided by conceptual or methodological frameworks. Reported conceptual frameworks included behavior change theories [12,29], perspectivist theory [14], democratic dialog theory [14], user experience framework [24], Ottawa decision support framework [26], medical research council framework [30], theoretical framework of social justice [38,39], self-determination theory [44,47,54], IDAS framework [44], nudging theory [44], and cultural historical activity theory [46]. Methodological frameworks included cooperative inquiry [13], appreciative inquiry [18], hermeneutics philosophy [19], ethnography [22], double diamond design process [35], action research [33,48,56,58], PICTIVE [55], and cooperative design [61]. Some workshop studies included in this review were guided by custom frameworks [32,40,59]. The dominant data analysis method was qualitative thematic analysis. Other inductive qualitative methods were also reported. Seven articles reported the use of multiple or mixed methods [15,52,57,67,68,72,73]. The majority of the workshops were audio and video recorded.

Although uncommon across studies, some distinct phases within or between workshops were identified. One study [22] organized two workshops and distinguished them as “creative” and “technical” workshops. Another [28] identified the following phases: exploration, ideation, reflection, and implementation. Jeffery et al. [32] identified three phases: priming, designing, and debriefing. Yet another [35] included the following phases: discovering, defining, developing, and delivering. One [59] identified three phases: scoping, participatory design, and prototyping. One study [61] identified four phases: user needs assessment, low fidelity prototyping, high fidelity prototyping, and functional prototyping. One [17] study identified three phases: Discovery; Evaluation; Prototype. Multiple studies used the phases from inception to implementation consistent with a system development life cycle: identification of needs, development/prototyping, and evaluation.

The level of workflow details reported in the included studies varied. Of the 62 studies, 11% (n = 7) described a formal evaluation, 60% (n = 32) a guiding framework, 63% (n = 39) the duration of the workshop, and 85% (n = 53) the participant selection as being critical components when planning a workshop but were not consistently reported.

Only seven [33,40,61,63,66,68,72] publications included data on the evaluation of the workshop. However, only five of them [61,63,66,68,72] reported a deliberate effort for evaluation. These efforts include asking verbal feedback within the whole group and/or a questionnaire. The other two collected feedback informally or extracted workshop evaluations indirectly from qualitative data that was originally collected for the design of focus. In the provided feedback, the evaluation of workflow could be intertwined with the evaluation of the design workshop focus. Table 2 shows a summary of the workshop evaluations.

Table 2.

Workshop evaluation results.

In summary, this study resulted in three important findings. First, the list of activities in conjunction with Table 1 highlighted that designers and researchers have various approaches to conduct workshops. Second, although the included studies reported rich findings overall, a lack of consistent evaluations prevented the ability to compare the effectiveness and appropriateness of workflow activities for different purposes. Third, workshops could possibly be utilized more frequently and fastidiously if the many workshop details are disseminated. These findings led to three themes as described in the discussion.

4. Discussion

This systematic review focused on workshops as a design and research activity in the domain of health informatics. This type of participation (i.e., workshops) presupposes the need to give voice to the users, rather than users just serving as a source of information or observation. Our review revealed three themes: (1) There are a variety of ways of conducting design workshops; (2) Workshops are effective design and research approaches; (3) Various levels of workflow details were reported. These themes can provide important insights on HIT development by providing a guidance to researchers and designers to operate and disseminate design workshops in a systematic and effective way.

4.1. There Are a Variety of Ways of Conducting Design Workshops

Designers and researchers have numerous workshop activity options as listed in the results section. Sanders et al. [74] identified three classes of workshop activities: (1) making tangible things; (2) acting, enacting, and playing; (3) talking, telling, and explaining. The workshops on the design of health informatics interventions have utilized approaches from all three classes. The selected studies do not provide sufficient details to assess whether any workshop activity is better than another, or if a specific workshop activity is superior (or inferior) in exploring a target technology design, participant characteristics, or other factors. However, we argue that the selected approach should be congruent with (1) the design problem, (2) participant characteristics, and (3) available resources. We also argue that a combination of multisensory eliciting activities (visual, auditory, tactile) within the same workshop will more thoroughly engage the participants, allowing for better absorption of material and understanding. This review is useful in terms of balancing tradeoffs between diverse workshop activities and combining multiple complimentary activities to further strengthen participant acumen and workshop efficaciousness.

Various participants may be more productive using different activities. For example, select participants can be more productive in making tangible things (e.g., prototyping), some participants can be more effective in acting and playing (e.g., role playing); and likewise, other participants can offer more dynamic input in talking and discussion (e.g., brainstorming) activities. Therefore, employing multiple types of workshop activities can best utilize diverse participant characteristics, therefore yielding an overall more productive workshop. Moreover, various participant characteristics such as disability status, developmental level, language barriers, and cultural sensitivities should be accounted for when selecting workshop activities.

Various conceptual and methodological frameworks have been used in organizing workshops. However, the contributions of the highlighted frameworks to the design process were implicit. Although there are frameworks specific to workshops (e.g., [75]) the adoption of these frameworks by workshop designers and researchers is ambiguous. Future studies should focus conceptual and methodological frameworks that link the research questions and design objectives to the workshop activities and deliverables.

4.2. Workshops Are Effective Design and Research Approaches

Participatory design suggests involving users throughout the entire design process. Design workshops should be a part of the broader participatory design process, in that they are emblematic of the values of this overall philosophy, creating a space in which designers and users can work together collaboratively to formulate design solutions. The success of a design workshop can be measured by its ability to bring out invisible or tacit knowledge. This study provides designers and researchers a variety of options to facilitate the capture of this hidden knowledge. As the workshops are more systematically evaluated, which activity is more suitable for different purpose and context will be better understood.

None of the included studies cautioned against identified weaknesses or lack of effectiveness and efficiencies of the design workshop. However, we present gaps both in terms of how such workshops have been evaluated and assessing the effectiveness of different types of strategies for different contexts.

Design workshops can improve the design of interventions that affect various subdomains of health informatics. However, these workshops focus on varied aspects of design, not necessarily examining implementation issues. Implementation workshops can complement design workshops and support adoption and sustainability of the informatics interventions that were developed within design workshops.

4.3. Various Levels of Workshop Details Were Reported

Replicating successful design workshop practices depend on disseminated details. The papers reported many details but lacked consistency across studies. Moreover, there are some details that were not reported by any studies. For example, all 62 studies included the overall number of participants in a workshop series but did not consistently report on the exact number of participants for each workshop, expertise, and demographic information of participants. Moreover, none of the studies provided full details on the selection of sample; how diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) issues (e.g., inclusion of vulnerable groups) were addressed; and any potential sampling bias.

We argue that any study that employs and reports on design workshops should report: the purpose, number of participants, selection of sample, how DEI issues are addressed, workshop duration, workshop agenda, details of conducted activities (e.g., activity identification, selection criteria), guiding framework(s) specific to the workshop (if applicable), expected and actual deliverables, and workshop evaluation process and results.

4.4. Recommendations for Conducting a Workshop

Based on our review, we developed the following recommendations for researchers and designers for organizing design workshops:

- The preparation/planning stage is critical for the success of the project. It is important to be cognizant of differing levels of aptitude. In some cases, participants may benefit from preworkshop technology education (e.g., brochures/pamphlets, emails) to elicit a better understanding of the technology or concepts novel to the participant, and subsequently support workshop participation preparedness.

- Well defined research/design questions/objectives should be the main drivers of other decisions related to organizing the workshop: participants, technology or intervention being designed, conceptual and methodological framework used, workshop activities employed. There should be a congruence among (1) research/design questions/objectives, (2) sampling, (3) selected activities, (4) technology/intervention that is being designed, (5) guiding framework, and (6) available resources.

- Sampling should reflect a wide range of user needs. Vulnerable populations should particularly be considered.

- An introduction may include an ice breaker/warm up exercise to establish commonality between participants and cultivate a trustful atmosphere with the facilitator.

- Workshops could benefit from a facilitator/moderator and a dedicated individual who will document the workshop activities and outcomes by taking notes or audio/video recording. Facilitators should be mindful of potential power imbalances in varied stakeholder groups that can result in a dominating one-sided perspective.

- A synergistic creating process can benefit from a relaxed environment, allowing for participants to freely move about and take breaks as needed. Providing coffee, snacks, or meals and encouraging a flexible atmosphere may encourage willingness for continued participation in an often time-intensive proceeding.

- Utilizing diverse activities will more likely provide better engagement and input, particularly for the heterogenous groups.

- Workshop conclusions should include a formal evaluation (e.g., an exit questionnaire, brief interviews, providing a visible note taking board to post feedback throughout the workshop) to provide structured feedback when the workshop findings are disseminated. If a formal evaluation is not feasible, the workshop may include debriefing or collective reflection to discuss participant experiences attained from design activities. This exercise dually acts as an informal evaluation of the successes and/or areas in need of improvement and validates the importance of participant contributions to the participant themselves.

These recommendations are the result of critiquing the literature and discussion with the research team. While this is not a comprehensive list of approaches, it provides our recommendations from the 62 studies. Included studies reported on in-person workshops. However, our recommendations potentially hold for conducting workshops remotely using computer mediation due to pandemics (e.g., COVID-19) or any situation that makes gathering impossible or impractical. Novel workshop activities specific to or more effective for remote workshops may be needed.

4.5. Limitations

A meta-analysis of study results was not possible because of the heterogeneity of the design and study results. We therefore provided a descriptive analysis of publications. We acknowledge that the retrieved studies do not necessarily represent a comprehensive list of all HIT workshops reported in the literature but list studies from the scientific literature returned during our search and that met our inclusion criteria.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/informatics8020034/s1, File S1: Detailed search strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.O., C.M.S. and R.S.V.; review, M.O., C.M.S. and O.F.; formal analysis, M.O. and C.M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.O. and C.M.S.; writing—review and editing, M.O., C.M.S., R.S.V. and O.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data Sharing not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Lilian Hoffecker for searching the literature and Suzanne Lareau for editorial support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kanstrup, A.M.; Madsen, J.; Nøhr, C.; Bygholm, A.; Bertelsen, P. Developments in Participatory Design of Health Information Technology—A Review of PDC Publications from 1990–2016. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2017, 233, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Merkel, S.; Kucharski, A. Participatory Design in Gerontechnology: A Systematic Literature Review. Gerontologist 2019, 59, e16–e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlowski, S.K.; Lawn, S.; Venning, A.; Winsall, M.; Jones, G.M.; Wyld, K.; Damarell, R.A.; Antezana, G.; Schrader, G.; Smith, D.; et al. Participatory Research as One Piece of the Puzzle: A Systematic Review of Consumer Involvement in Design of Technology-Based Youth Mental Health and Well-Being Interventions. JMIR Hum. Factors 2015, 2, e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spinuzzi, C. The Methodology of Participatory Design. Tech. Commun. 2005, 52, 163–174. [Google Scholar]

- Kushniruk, A.; Nøhr, C. Participatory Design, User Involvement and Health IT Evaluation. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2016, 222, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ozkaynak, M.; Valdez, R.S.; Holden, R.J.; Weiss, J. Infinicare framework for an integrated understanding of health-related activities in clinical and daily-living contexts. Health Syst. 2018, 7, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Brazil, J.; Ozkaynak, M.; Desanto, K. Evaluative Research of Technologies for Prehospital Communication and Coordination: A Systematic Review. J. Med. Syst. 2020, 44, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozkaynak, M.; Metcalf, N.; Cohen, D.M.; May, L.S.; Dayan, P.S.; Mistry, R.D. Considerations for Designing EHR Embedded Clinical Decision Support Systems for Antimicrobial Stewardship in Pediatric Emergency Departments. Appl. Clin. Inform. 2020, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez, R.S.; Holden, R.J.; Novak, L.L.; Veinot, T.C. Transforming consumer health informatics through a patient work framework: Connecting patients to context. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2014, 22, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez, R.S.; Holden, R.J.; Novak, L.L.; Veinot, T.C. Technical infrastructure implications of the patient work framework. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2015, 22, e213–e215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. for the PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, 1006–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amann, J.F.M.; Brach, M.; Bertschy, S. Scheel-Sailer, A.; Rubinelli, S. Co-designing a Self-Management App Prototype to Support People With Spinal Cord Injury in the Prevention of Pressure Injuries: Mixed Methods Study. JMIR MHealth UHealth 2020, 8, e18018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aufegger, L.B.K.H.; Bicknell, C.; Darzi, A. Designing a paediatric hospital information tool with children, parents, and healthcare staff: A UX study. BMC Pediatrics 2020, 20, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burford, S.P.S.; Dawda, P.; Burns, J. Participatory research design in mobile health: Tablet devices for diabetes self-management. Commun. Med. 2015, 12, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castensoe-Seidenfaden PRH, G.; Teilmann, G.; Hommel, E.; Olsen, B.S.; Kensing, F. Designing a Self-Management App for Young People With Type 1 Diabetes: Methodological Challenges, Experiences, and Recommendations. JMIR MHealth UHealth 2017, 5, e124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro-Sanchez, E.S.A.; Rawson, T.M.; Firth, J.; Holmes, A.H. Forecasting Implementation, Adoption, and Evaluation Challenges for an Electronic Game-Based Antimicrobial Stewardship Intervention: Co-Design Workshop With Multidisciplinary Stakeholders. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e13365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, V.W.S.D.T.A.; Johnson, D.; Vella, K.; Mitchell, J.; Hickie, I.B. An App That Incorporates Gamification, Mini-Games, and Social Connection to Improve Men’s Mental Health and Well-Being (MindMax): Participatory Design Process. JMIR Ment. Health 2018, 5, e11068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtis, K.B.S. Digital health technology: Factors affecting implementation in nursing homes. Nurs. Older People 2020, 32, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danbjorg, D.B.V.A.; Gill, E.; Rothmann, M.J.; Clemensen, J. Usage of an Exercise App in the Care for People With Osteoarthritis: User-Driven Exploratory Study. JMIR MHealth UHealth 2018, 6, e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, S.R.P.D.; Calvo, R.A.; Sawyer, S.M.; Foster, J.M.; Smith, L. “Kiss myAsthma”: Using a participatory design approach to develop a self-management app with young people with asthma. J. Asthma 2018, 55, 1018–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, T.M.S.; Stasiak, K.; Hopkins, S.; Patolo, T.; Rum, S.; Lau, M.; Shepherd, M.; Christie GGoodyear-Smith, F. The Importance of User Segmentation for Designing Digital Therapy for Adolescent Mental Health: Findings from Scoping Processes. JMIR Mental Health 2019, 6, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garne Holm, K.B.A.; Zachariassen, G.; Smith, A.C.; Clemensen, J. Participatory design methods for the development of a clinical telehealth service for neonatal homecare. SAGE Open Med. 2017, 5, 2050312117731252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giordanengo, A.O.P.; Hansen, A.H.; Arsand, E.; Grottland, A.; Hartvigsen, G. Design and Development of a Context-Aware Knowledge-Based Module for Identifying Relevant Information and Information Gaps in Patients with Type 1 Diabetes Self-Collected Health Data. JMIR Diabetes 2018, 3, e10431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giroux, D.T.M.; Latulippe, K.; Provencher, V.; Poulin, V.; Giguere, A.; Dube, V.; Sevigny, A.; Guay, M.; Ethier, S.; Carignan, M. Promoting Identification and Use of Aid Resources by Caregivers of Seniors: Co-Design of an Electronic Health Tool. JMIR Aging 2019, 2, e12314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonsalves, P.P.H.E.S.; Kumar, A.; Aurora, T.; Chandak, Y.; Sharma, R.; Michelson, D.; Patel, V. Design and Development of the “POD Adventures” Smartphone Game: A Blended Problem-Solving Intervention for Adolescent Mental Health in India. Front. Public Health 2019, 7, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, M.H.R.; Holmes, J.H.; Wolters, M.K.; Bennett, I.M. Spirit Stress Pregnancy Improving. Participatory design of ehealth solutions for women from vulnerable populations with perinatal depression. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2016, 23, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, T.P.R.; Wherton, J.; Sugarhood, P.; Hinder, S.; Rouncefield, M. What is quality in assisted living technology? The ARCHIE framework for effective telehealth and telecare services. BMC Med. 2015, 13, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grenha Teixeira, J.P.N.F.; Patricio, L. Bringing service design to the development of health information systems: The case of the Portuguese national electronic health record. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2019, 132, 103942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemingway, C.B.E.S.; Dalmacion, G.V.; Medina, P.M.B.; Guevara, E.G.; Sy, T.R.; Dacombe, R.; Dormann, C.; Taegtmeyer, M. Development of a Mobile Game to Influence Behavior Determinants of HIV Service Uptake Among Key Populations in the Philippines: User-Centered Design Process. JMIR Serious Games 2019, 7, e13695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobson, E.V.B.W.O.; Partridge, R.; Cooper, C.L.; Mawson, S.; Quinn, A.; Shaw, P.J.; Walsh, T.; Wolstenholme, D. McDermott, C.J. The TiM system: Developing a novel telehealth service to improve access to specialist care in motor neurone disease using user-centered design. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2018, 19, 351–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- How, T.V.H.A.S.; Green, R.E.A.; Mihailidis, A. Envisioning future cognitive telerehabilitation technologies: A co-design process with clinicians. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2017, 12, 244–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeffery, A.D.N.L.L.; Kennedy, B.; Dietrich, M.S.; Mion, L.C. Participatory design of probability-based decision support tools for in-hospital nurses. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2017, 24, 1102–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, C.M.O.S.; Wiil, U.K.; Smith, A.C.; Clemensen, J. Bridging the gap: A user-driven study on new ways to support self-care and empowerment for patients with hip fracture. SAGE Open Med. 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jessen, S.M.J.; Ruland, C.M. Creating Gameful Design in mHealth: A Participatory Co-Design Approach. JMIR MHealth UHealth 2018, 6, e11579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessen, S.M.J.; Nes, L.S. MyStrengths, a Strengths-Focused Mobile Health Tool: Participatory Design and Development. JMIR Form. Res. 2020, 4, e18049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemets, J.T.P. Availability Communication: Requirements for an Awareness System to Support Nurses’ Handling of Nurse Calls. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2015, 216, 103–107. [Google Scholar]

- Kocaballi, A.B.I.K.; Laranjo, L.; Quiroz, J.C.; Rezazadegan, D.; Tong, H.L.; Willcock, S.; Berkovsky, S.; Coiera, E. Envisioning an artificial intelligence documentation assistant for future primary care consultations: A co-design study with general practitioners. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2020, 27, 1695–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latulippe, K.H.C.; Giroux, D. Co-Design to Support the Development of Inclusive eHealth Tools for Caregivers of Functionally Dependent Older Persons: Social Justice Design. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e18399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latulippe, K.H.C.; Giroux, D. Integration of Conversion Factors for the Development of an Inclusive eHealth Tool With Caregivers of Functionally Dependent Older Persons: Social Justice Design. JMIR Human Factors 2020, 7, e18120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.S.M.; Asmussen, H.C.; Skougaard, M.; Macdonald, J.; Zavada, J.; Bliddal, H.; Taylor, P.C.; Gudbergsen, H. The Development of Complex Digital Health Solutions: Formative Evaluation Combining Different Methodologies. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2018, 7, e165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundin, M.M.A. Co-designing technologies in the context of hypertension care: Negotiating participation and technology use in design meetings. Inform. Health Soc. Care 2017, 42, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupton, D. Digital health now and in the future: Findings from a participatory design stakeholder workshop. Digit. Health 2017, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marent, B.H.F.; Darking, M. Em, Erge Consortium. Development of an mHealth platform for HIV Care: Gathering User Perspectives Through Co-Design Workshops and Interviews. JMIR MHealth UHealth 2018, 6, e184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, A.C.M.; Adorni, F.; Andreoni, G.; Ascolese, A.; Atkinson, S.; Bul, K.; Carrion, C.; Castell, C.; Ciociola, V.; Condon, L.; et al. A Mobile Phone Intervention to Improve Obesity-Related Health Behaviors of Adolescents Across Europe: Iterative Co-Design and Feasibility Study. JMIR MHealth UHealth 2020, 8, e14118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Hammond, A.V.S.; Rao, K. Exploring Older Adults’ Beliefs About the Use of Intelligent Assistants for Consumer Health Information Management: A Participatory Design Study. JMIR Aging 2019, 2, e15381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moen, A.S.O. RareICT: A web-based resource to augment self-care and independence with a rare medical condition. Work 2012, 41, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeemabadi, M.S.J.H.; Klastrup, A.; Schlunsen, A.P.; Lauritsen, R.E.K.; Hansen, J.; Madsen, N.K.; Simonsen, O.; Andersen, O.K.; Kim, K.K.; Dinesen, B. Development of an individualized asynchronous sensor-based telerehabilitation program for patients undergoing total knee replacement: Participatory design. Health Inform. J. 2020, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, C.A.H.; Bistrup, C.; Clemensen, J. User involvement in the development of a telehealth solution to improve the kidney transplantation process: A participatory design study. Health Inform. J. 2020, 26, 1237–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noergaard, B.S.M.; Rottmann, N.; Johannessen, H.; Wiil, U.; Schmidt, T.; Pedersen, S.S. Development of a Web-Based Health Care Intervention for Patients With Heart Disease: Lessons Learned From a Participatory Design Study. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2017, 6, e75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ospina-Pinillos, L.D.T.; Mendoza Diaz, A.; Navarro-Mancilla, A.; Scott, E.M.; Hickie, I.B. Using Participatory Design Methodologies to Co-Design and Culturally Adapt the Spanish Version of the Mental Health eClinic: Qualitative Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e14127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ospina-Pinillos, L.D.T.A.; Navarro-Mancilla, A.A.; Cheng, V.W.S.; Cardozo Alarcon, A.C.; Rangel, A.M.; Rueda-Jaimes, G.E.; Gomez-Restrepo, C.; Hickie, I.B. Involving End Users in Adapting a Spanish Version of a Web-Based Mental Health Clinic for Young People in Colombia: Exploratory Study Using Participatory Design Methodologies. JMIR Ment. Health 2020, 7, e15914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peiffer-Smadja, N.P.A.; Ouedraogo, A.S.; Guiard-Schmid, J.B.; Delory, T.; Le Bel, J.; Bouvet, E.; Lariven, S.; Jeanmougin, P.; Ahmad, R.; Lescure, F.X. Paving the Way for the Implementation of a Decision Support System for Antibiotic Prescribing in Primary Care in West Africa: Preimplementation and Co-Design Workshop With Physicians. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e17940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peiris-John, R.D.L.; Sutcliffe, K.; Kang, K.; Fleming, T. Co-creating a large-scale adolescent health survey integrated with access to digital health interventions. Digit. Health 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, D.D.S.; Calvo, R.A.; Sawyer, S.M.; Smith, L.; Foster, J.M. Young People’s Preferences for an Asthma Self-Management App Highlight Psychological Needs: A Participatory Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017, 19, e113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollack, A.H.M.A.; Mishra, S.R.; Pratt, W. PD-atricians: Leveraging Physicians and Participatory Design to Develop Novel Clinical Information Tools. AMIA Annu. Symp. Proc. AMIA Symp. 2016, 2016, 1030–1039. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ravn Jakobsen, P.H.A.P.; Sondergaard, J.; Wiil, U.K.; Clemensen, J. Development of an mHealth Application for Women Newly Diagnosed with Osteoporosis without Preceding Fractures: A Participatory Design Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawson, T.M.M.L.S.P.; Castro-Sanchez, E.; Charani, E.; Hernandez, B.; Alividza, V.; Husson, F.; Toumazou, C.; Ahmad, R.; Georgiou, P.; Holmes, A.H. Development of a patient-centred intervention to improve knowledge and understanding of antibiotic therapy in secondary care. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2018, 7, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Revenäs, A.O.C.H.; Demmelmaier, I.; Keller, C.; A˚senlöf, P. Development of a Web and Mobile Application (WeMApp) to support physical activity in rheumatoid arthritis: Results from the second step of a co-design process. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 2014, 43, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Robinson, L.B.K.; Lindsay, S.; Jackson, D.; Olivier, P. Keeping In Touch Everyday (KITE) project: Developing assistive technologies with people with dementia and their carers to promote independence. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2009, 21, 494–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruland, C.M.S.L.; Starren, J.; Vatne, T.M. Children as design partners in the development of a support system for children with cancer. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2006, 122, 80–85. [Google Scholar]

- Scandurra, I.S.M. Participatory Design with Seniors: Design of Future Services and Iterative Refinements of Interactive eHealth Services for Old Citizens. Medicine 20 2013, 2, e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sin, J.H.C.; Woodham, L.A.; Sese Hernandez, A.; Gillard, S. A Multicomponent eHealth Intervention for Family Carers for People Affected by Psychosis: A Coproduced Design and Build Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e14374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swallow, D.P.H.; Power, C.; Lewis, A.; Edwards, A.D. Involving Older Adults in the Technology Design Process: A Case Study on Mobility and Wellbeing in the Built Environment. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2016, 229, 615–623. [Google Scholar]

- Terp, M.L.B.S.; Jorgensen, R.; Mainz, J.; Bjornes, C.D. A room for design: Through participatory design young adults with schizophrenia become strong collaborators. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2016, 25, 496–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tremblay, M.L.K.; Giguere, A.M.; Provencher, V.; Poulin, V.; Dube, V.; Guay, M.; Ethier, S.; Sevigny, A.; Carignan, M.; Giroux, D. Requirements for an Electronic Health Tool to Support the Process of Help Seeking by Caregivers of Functionally Impaired Older Adults: Co-Design Approach. JMIR Aging 2019, 2, e12327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Besouw, R.M.O.B.R.; Hodkinson, S.M.; Polfreman, R.; Grasmeder, M.L. Participatory design of a music aural rehabilitation programme. Cochlear Implant. Int. 2015, 16 (Suppl. 3), S39–S50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wannheden, C.R.A. How People with Parkinson’s Disease and Health Care Professionals Wish to Partner in Care Using eHealth: Co-Design Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e19195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, L.R.H.M.; Arora, S.; Darzi, A. Working with patients and the public to design an electronic health record interface: A qualitative mixed-methods study. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2019, 19, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wherton, J.S.P.; Procter, R.; Hinder, S.; Greenhalgh, T. Co-production in practice: How people with assisted living needs can help design and evolve technologies and services. Implement. Sci. 2015, 10, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winterling, J.W.M.; Obol, C.M.; Lampic, C.; Eriksson, L.E.; Pelters, B.; Wettergren, L. Development of a Self-Help Web-Based Intervention Targeting Young Cancer Patients with Sexual Problems and Fertility Distress in Collaboration With Patient Research Partners. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2016, 5, e60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, L.C.E.; Duff, J.; Walker, K. Conceptual Design and Iterative Development of a mHealth App by Clinicians, Patients and Their Families. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2018, 252, 170–175. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.G.K.; Koh, M.; Lum, E.; Tan, W.S.; Thng, S.; Car, J. Creating a Smartphone App for Caregivers of Children With Atopic Dermatitis With Caregivers, Health Care Professionals, and Digital Health Experts: Participatory Co-Design. JMIR MHealth UHealth 2020, 8, e16898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.H.S.; Song, G.; Fung, D.S.; Smith, H.E. Co-designing a Mobile Gamified Attention Bias Modification Intervention for Substance Use Disorders: Participatory Research Study. JMIR MHealth UHealth 2019, 7, e15871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, E.B.-N.; Brandt, E.; Binder, T. A framework for organizing the tools and techniques of participatory design. In Proceedings of the 11th Biennial Participatory Design Conference, Sydney, Australia, 29 November–3 December 2010; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 195–198. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Hinton, L.; Finlay, T.; Macfarlane, A.; Fahy, N.; Clyde, B.; Chant, A. Frameworks for supporting patient and public involvement in research: Systematic review and co-design pilot. Health Expect. 2019, 22, 785–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).