How The Arts Can Help Tangible Interaction Design: A Critical Re-Orientation

Abstract

:1. Introduction: Digital Arts and Tangible Interaction Design

2. Interface Aesthetics

2.1. Interfaces as Aesthetic Artifacts

- An extension of tangible interface design towards aesthetics shifts the perception of interfaces as strict functional objects to a vision of interfaces as artifacts with an expressive intention, as long as their components, representations, and interactions can afford aesthetic relationships. As a consequence, interfaces can appear highly disembodied of their original functionalities at the level of the computer system. For instance, a computer keyboard attached to a tennis racket which allows typing on facebook while its user is playing can probably afford aesthetic relationships (an idea inspired on the artwork Writing_racket by the artist César Escudero Andaluz). However, if some of its keys happen to get broken after the impact with a tennis ball, the aesthetic experience will not be affected decisively. The work is mostly about the act of random typing and some broken keys would not radically change its expressiveness.However, it is important to clarify that “the aesthetic” does not define itself as the opposite to “the functional”. Aesthetic extensions re-organize many elements of artifacts towards an expressive or artistic intention. This is a typical mechanism of the Arts. A classic example is Man Ray’s work Cadeau (Figure 1), where a flat iron of the sort that had to be heated on a stove is transformed into a dysfunctional, disturbing object by the addition of a single row of fourteen nails. The transformation of an item of ordinary domestic life into a strange, unnameable object with sadistic connotations exemplifies the power of the artistic methods.Indeed, the aesthetic dimension of an interface does not act against its functional part. In fact, aesthetics and functionalities always engage together at the game of expressiveness: they are both active agents at the dialectic nature of interfaces. That makes it possible, for instance, that a non-functional interface could be expressive too. In fact, a lack of function always alludes to the already known original functionality of the interface. Thus, the aesthetic reconfigures but never acts against functionality.

- If these aesthetic interfaces are also critical with their research medium, they can become a language and a valid medium for research. They can engage us in aesthetic experiences, but they can also serve us well to evaluate the validity of accepted assumptions regarding design and user experience in our research medium. In conclusion, they can be used as a methodology for research within HCI. This possibility is studied in the following section.

2.2. Critical Interfaces

- Evaluating our accepted assumptions about HCI design

- Proposing alternative models inside HCI which could better assess aspects of user experience and interaction

“Instead of focusing only on functionality and effects, digital art explores the current materiality and cultural results of the interface’s representational effects. What are the representational languages of the interface, how does it work as text, image, sound, space and so forth, and what are the cultural effects, for instance, of the way it reconfigures the visual, textual or auditory? How does the interface reconfigure aesthetics and what does it do to representation, communication and, in continuation of this, the social and the political?”

2.3. Traditional Visions about the Arts in HCI

“This (Transform) is a white canvas, paintbrush and ink waiting for a Picasso” [20].

2.4. Artistic Research Methodologies

3. Examples

- Artworks dealing with Functional realism: those visualizing the functional elements of the instrumental medium as components with aesthetic possibilities. Those artworks making use of operational elements of the interface which can be constituted of some aesthetic value. For example, artworks hacking hardware or software components or reconfiguring some functionality to create unexpected situations.

- Artworks dealing with Media realism: artworks going beyond the visual surface of the interface towards the imperceptible and unreadable code. Artworks of these type can, for instance, show the codes behind the screen and reveal the normally hidden flow of codes that the user interaction causes.

- Artworks dealing with Illusionistic realism: artworks beyond pure representation, interfaces maximizing reality towards immersive simulation. These artworks make the user forget about the interface and become immersed in the illusionistic world it presents.

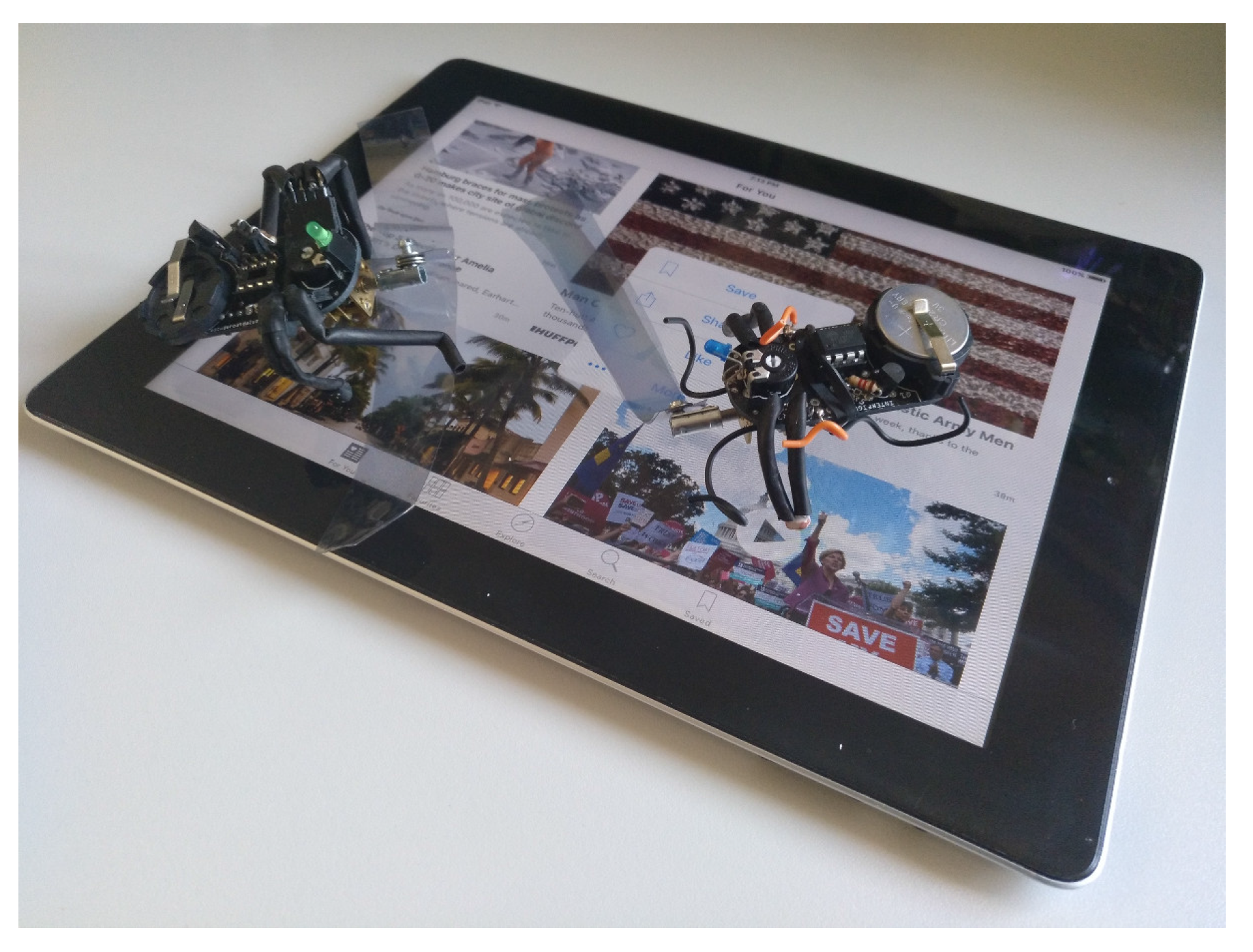

3.1. Interfight: Functional and Media Realism

- Interface design homogenization: Currently, many commercial websites track human input activity with hidden services to automatically improve their GUI (graphical user interface) design using machine learning strategies. Interfight makes us aware of this issue and pollutes those tracking services with random data produced by physical bots. They are a mechanism against interface design homogenization.

- Against stable interfaces: These artificial bugs entangle and reconfigure the graphical interface in strange ways, re-arranging desktop appearances and graphical customizations. They work as a mechanism against the principle of “perceived stability” [28], which defend the idea that the elements in the computer interface should not be changed without the user’s involvement.

- Bodily interaction: Touch interfaces limit our bodily interaction to an extreme degree—we are radically reduced to the surface of our finger tips. That is what makes simulating physical human input so easy.Interfight questions why have we accepted that other parts of our body are not suitable for interaction. Or maybe, should we extend our fingers with other non-human artifacts?

3.2. Hatching Scarf: Illusionistic Realism

"In HCI there are many applications and tangible objects that focus on how we can measure quantified data about ourselves, which encourage us to pursue desired behavior and to support our achievement of goals. Yet to what extent do many of these persuasive technologies inadvertently contribute to unhealthy anxieties?".

- Self-identification at interaction. Hatching Scarf attempts to study how we identify and represent ourselves by experiencing the aesthetics of interaction. Evoking critical thinking via socially engaged objects, the work explores the concept of “extended self”: how one’s “colors” may by revealed depending on their personal history, philosophical differences, perception gaps, experience, interests, culture, education, and so on.

- The language of design: Interface rules and intentions are communicated using different levels of rhetorics to grab the user’s attention [31]: informative (rational and without emotional impact), entertaining (with a soft emotional impact), and affective (with high impact to persuade audiences). Hatching Scarf makes us aware that these strategies for communication are also designed, and lets us consider if the language of the interfaces we use daily are always adequate for our emotional situations.

- Personal affection of design: Designs in HCI can carry or generate unexpected personal conflicts and anxieties to its users. Are devices solving our needs or generating new personal issues? Hatching Scarf—an artificial device—puts us in an estranging situation simply by eating some pieces of chocolate. Thus, the work encourages us as interface users to reflect on our persons as both objects and subjects of knowledge which are affected by the characteristics of certain design decisions.

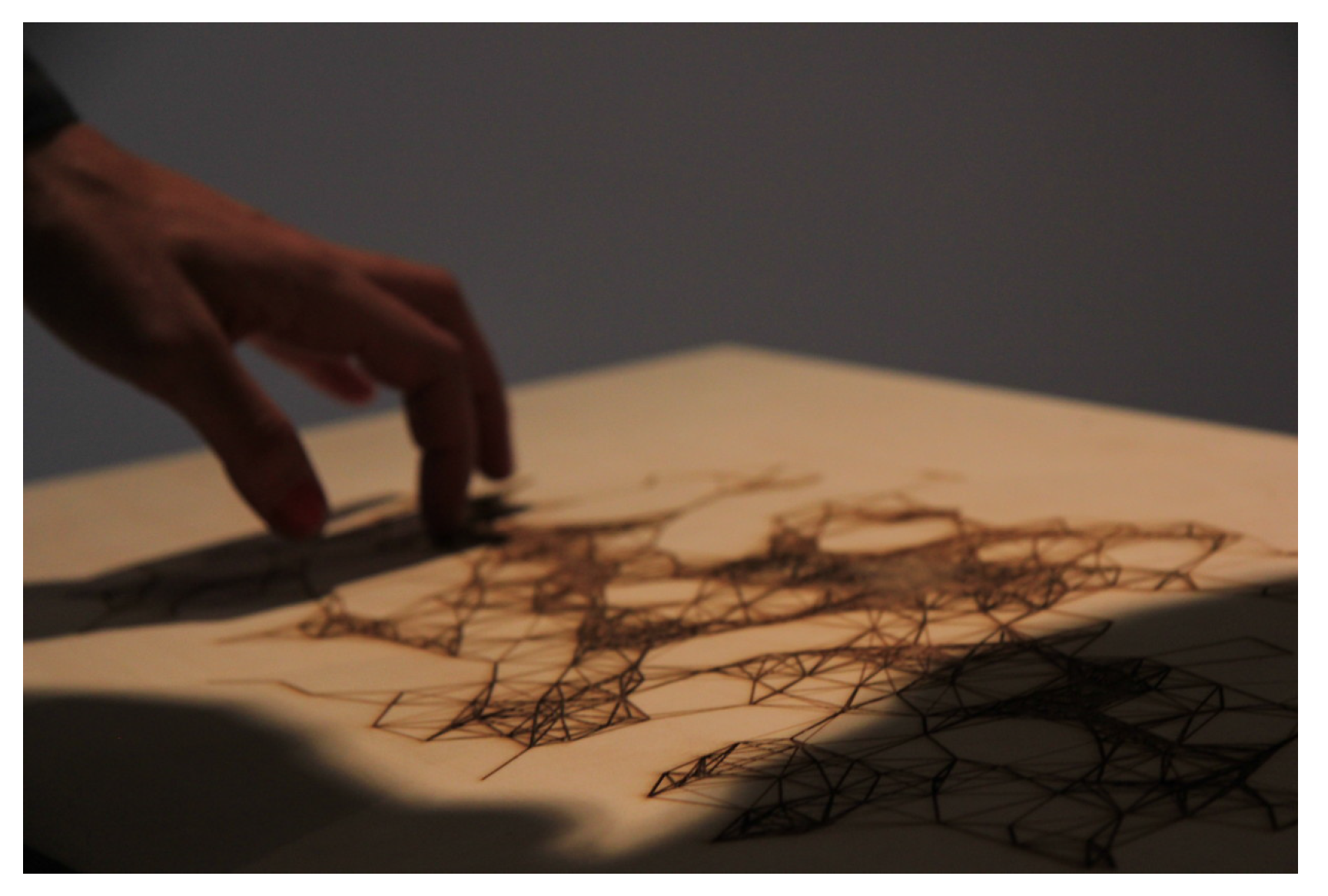

3.3. Tangible Scores: Media and Illusionistic Realism

- Non-linguistic communication: In a Tangible Score there are no explicit symbols on the interface which can be explored by the users, only a continuum of materiality. Users are confronted with a total absence of information about how they can manipulate the different parameters controlling the sonic engine. The interface makes us aware of the hyper-abundance of symbols present at interaction design, making us reflect on the issues that the great dependence on cognitive and linguistic communication has created on musical expression [34].

- Performative materiality: With a Tangible Score users are forced to “think the materiality” they find in front of themselves. In fact, the project Tangible Scores was inspired by the recent theories of New Materialism which investigate “the incessant materialization of the world” [35]. Under this theory, matter is not a stable substance. The agency of materials cannot be described until they are performed. In this context, Tangible Scores aims at discovering the performative properties every material features (our interfaces too), remarking on the importance of the physical materiality of our interfaces.

4. Discussion

- Problematization. The systematization of artistic research projects within HCI as problem-solving processes has been been suggested by Oulasvirta and Hornbaek [36]. For the authors, the problematization of some artistic practice can help to transform an artistic process into a process of research, even more than enveloping it together with some theoretical discourse. To illustrate this model, let us imagine the case of a photographer who problematizes how she can better approach certain critical discourse about a community of people within her practice. For her, she will solve her research problem if she finds an adequate solution to communicate specific concepts within her work through some expressive means.

- Methodological conceptualization. After having problematized the artistic research case, artists will need to choose among different methodologies for carrying out their research, or even a combination of various methodologies. Following the example of the photographer, let us imagine that she decides to make use of some ethnographic research method, studying the culture and social organization of the community on which she is focusing her work. The data obtained from this ethnographic process serves to create a theoretical analysis of her practice which will be used to transfer her conclusions again into practice.

- Artistic inquiry. The conceptual element—the theory behind the practice or the phenomena being researched—will now need material inquiry and material perception. Again, in the example of the photographer, she will now work in the field taking photographs, but having a more substantiated and developed strategy for remarking on aspects she finds interesting for her work. Undoubtedly, the new design process will likely create new theoretical questions. Thus, a permanent cycle between the conceptual and the material elements is produced, forcing the researcher to learn, and sometimes producing new approaches or new artworks.

4.1. Problematization of the Examples

- The idea for producing Interfight came from an invitation from the research program MEMBRANA, a residency for “Artistic Interface Criticism” offered by Hangar (Barcelona, Spain) aimed at providing support to a visual artist interested in developing an artwork based on the concept of interface, and participating in the investigation of a critical interface manifesto. Thus, Escudero Andaluz problematized his project as follows: Is it possible to create an interface-artifact to criticize the actual effects of computer interfaces? Which are the aspects of interfaces which are not visible and interesting to communicate nowadays?

- Hatching Scarf comes from the problematization of a personal intuition. The fundamental theme in Young Suk Lee’s work concerns how “ecosystems, societies, and life itself form an interconnected web where the disturbance of any part affects everything. As human beings an inescapable part of life is our interaction with other creatures” [29]. For the artist, environmental influences evoke inevitable engagements with social norms. This forces one to adopt socially desired ideals in response to certain pleasures, attitudes, etc. Thus, the research in Hatching Scarf attempts to solve the problem of creating socially engaged artistic artifacts which can help to show how one becomes fragile in nervous situation under societal influence.

- Tangible Scores appears as part of the PhD of this author at the Kunstuniversität of Linz. The spark for creating it comes from a research question: Is there the possibility of creating musical interfaces incorporating the idea of “musical score” in their configuration? What could be the philosophical and practical consequences of understanding musical interfaces as musical scores? This question arose after the observation that many electronic music instruments carry equally the notion of instrument and composition [32].

4.2. Methodologies of the Examples

- Interfight makes use of the Media Analysis methodology. This methodology suggests the examination, interpretation, and critique of both the material content of the channels of communication media and the structure, composition, and operations of corporations that either own or control those media—in this case, the Internet. For its development, Escudero Andaluz investigated different strategies of control that companies are using on the Internet without informing their users. Among different possibilities, the artist found it suitable to work with those hidden tracking services for GUI optimization. For instance, many websites track the path users make with their pointers on screen while navigating their pages or the pixels where they usually stop more often, etc. Thus, through this methodology, the artist obtained enough data to fully understand fully the issue and be able to respond with an artistic artifact.

- Hatching Scarf shows a typical example of Critical Discourse as methodology. It asserts that human interaction and social practices are tied to specific historical contexts and are the means by which existing social relations are reproduced or contested and by which different interests are served. It deals with the questions pertaining to interests that relate discourse to relations of power. The methodology accompanying Hatching Scarf criticizes the social aspects of HCI’s language of design, thus giving enough examples of devices and clinic cases of study which inspired the final artwork.

- Tangible Scores appears as a clear case of Practice-Based research. In this case, the author’s practice (concerts, composition, etc.) with the interface is the basis of the contribution to knowledge. While the significance and context of the research claims could be described in words, a full understanding can only be obtained with direct reference to the practice outcomes. With Tangible Scores, many aspects of its contributions to research come after the direct observation of the artifact created, once it exists. Thus, following this methodology, the artifact informs the author important concepts which were in fact not formulated at the moment of design and performance: they can only be perceived at the moment of experiencing it, at the moment of practice. Performing a Tangible Score means here the production of creative enactments in the relationships created between our bodies and the materiality of the interface, be it at a live performance on stage, at an exhibition, or any other form of presentation.

4.3. Artistic Inquiry of the Examples

- Interfight follows the aesthetics of dysfunction, understood as an artistic practice emerging from the alteration of the functional change of some of the physical elements of an electronic artifact, affecting part of the interaction between a device and its users. The dysfunctional strategy reconfigures the original “reason to exist” of devices. At the same time, dysfunctions can create new unexpected—even ironic—relationships with the objects, shifting the original intention of an artifact from the functional to the artistic or poetic.Transforming a tablet device into a dysfunctional artifact made it possible to communicate the author’s critical intention. Escudero Andaluz extended the interface with elements (the robots) that can interact with capacitive screens. Those small robots equipped with conductive plastics create valid human input interaction to confuse on-line tracking algorithms. If convincing a user to act randomly for hours in front of a tablet sounds difficult, here those small and simple robots show themselves as quite efficient at that task.

- Hatching Scarf: in this case, the artwork follows the aesthetics of estrangement as an expressive strategy. The wearable transforms its user into a kind of artificial bird, while the aspect and movement of the scarf creates a deep sentiment of estrangement. The inclusion of the colors red and black, and even jewelry reminiscent of the form of larvae contributes to this perception.The strategy of estrangement is typical of the Arts [38]. However, it has been used as a successful method for improving or suggesting novel design developments in tangible interaction [39,40]. Being confronted with a certain estrangement requires re-learning of the environment, bringing the mind and body to unfamiliar situations, therefore producing certain enactment of reflection and new embodied relationships. For Wilde, Vallgårda, and Tomico [40], estrangement creates a confusion which prolongs the moment of arriving to an understanding, hence provoking a deeper and more intimate relationship with the concepts and materialities the situation carries. These authors proposed a framework for analyzing estrangement in HCI following an iterative process of answering “what is done to disrupt”, “what is destabilized”, “what emerges”, and “what the whole embodies”. Thus, for Hatching Scarf:

- The physical aspect of the socially engaged wearable is made to disrupt, to make the user feel estranged.

- The self-representation of oneself during interaction and the communication with others gets destabilized.

- It emerges a reflection about how certain types of HCI design can create personal anxieties to their users in socially constrained environments.

- The whole process embodies knowledge about the risks of choosing inadequate languages of design (e.g., in the case of technology dedicated to children). Additionally, it embodies a full identification with other people suffering certain personal affections when using technology in certain personal, social, or political situations. Why is the simple action of interacting making me feel estranged? Is it because it visualizes my concerns about snacking and my weight?

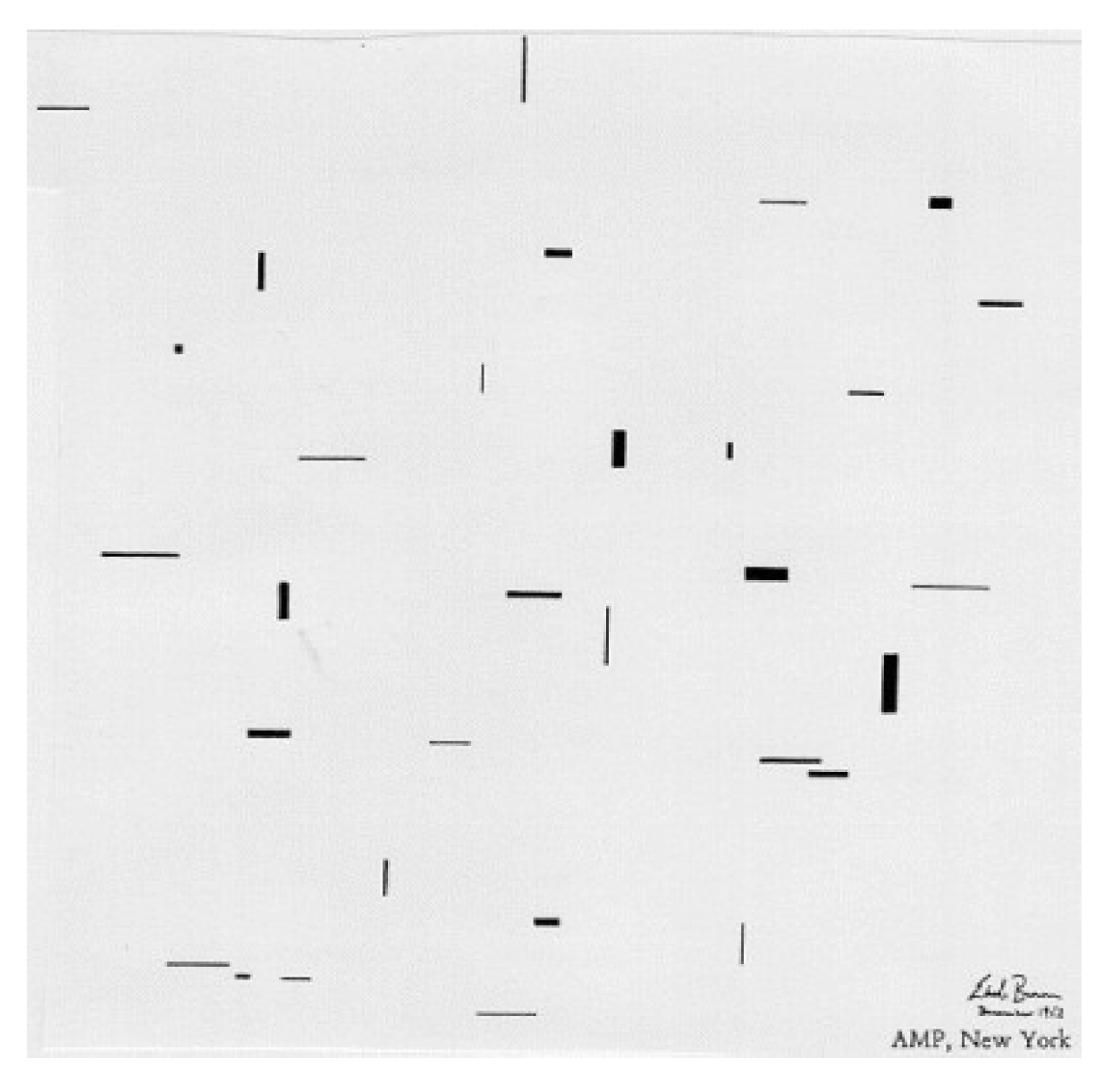

- Tangible Scores follows an aesthetic strategy inspired by graphic scores [32]. Graphic scores appeared in the musical avant-garde as a way to release composers from the constraints of writing their music using the notation of a traditional score. Consequently, the representation of a musical idea opened to the personal and subjective selection of graphic figures that inspire new and imaginative ways of interpretation. One of its earliest examples can be seen in Figure 5, Earle Brown’s November 1952.

5. Conclusions: How the Arts Can Help Tangible Interaction Design

- Adopting a critical attitude with our own research medium: tangible interaction. Artworks can act as breakdowns of the standard discourses of tangible interaction design. They should serve us to discover new interpretations and notions, often unfolding the tension among established notions of our fields of study and their real value in our societies.

- Adopting the format of artistic research. The Arts are a valid medium for research. The Arts create a type of knowledge which is not afforded by traditional HCI methodologies—especially in the case of embodied technologies. However, research in the Arts should have a clear formalized structure and a clear focus. Finally, it may rely on the problematization of its aims and the proposal of alternative methodologies.

- Avoiding the instrumentalization of its artistic process: The artist’s role deals more with a permanent questioning of the inner pillars of the research field. It must be more to do with destabilizing than with supporting what has already been fixed. Artists should not start their research process at the end of the HCI research chain.

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TEI | International Conference on Tangible, Embedded and Embodied Interactions |

| HCI | Human–Computer Interaction |

| GUI | Graphical User Interface |

References

- Stocker, G.; Schöpf, C.; Leopoldseder, H. The Alchemists of Our Time. Exhibition Catalogue of the Ars Electronica Festival 2016, Linz, Austria, 8–12 September 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ishii, H.; Lakatos, D.; Bonanni, L.; Labrune, J. Radical atoms: Beyond tangible bits, toward transformable materials. Mag. Interact. 2012, 19, 38–51. [Google Scholar]

- Jordà, S. The reactable: Tangible and tabletop music performance. In Proceedings of the CHI 2010 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Atlanta, GA, USA, 10–15 April 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ullmer, B.; Schmidt, A. Chairs Foreword. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Tangible and Embedded Interaction, Baton Rouge, LA, USA, 15–17 February 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hornecker, E.; Buur, J. Getting a grip on tangible interaction: A framework on physical space and social interaction. In Proceedings of the CHI 2006 SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Montréal, QC, Canada, 22–27 April 2006; pp. 437–446. [Google Scholar]

- Iles, C. Dreamlands: Immersive Cinema and Art, 1905–2016; Whitney Museum of American Art and Yale University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Shanken, E.A. Art and Electronic Media; Phaidon Press: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fernaeus, Y.; Tholander, J.; Jonsson, M. Towards a new set of ideals: Consequences of the practice turn in tangible interaction. In Proceedings of the TEI 2008 2nd International Conference on Tangible and Embedded Interaction, Bonn, Germany, 18–20 February 2008; pp. 223–230. [Google Scholar]

- Hornecker, E. Tangible Interaction; The Glossary of Human Computer Interaction, Interaction Design Foundation. 2015. Available online: https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/book/the-glossary-of-human-computer-interaction/tangible-interaction (accessed on 14 September 2017).

- Pold, S. Interface Realisms: The Interface as Aesthetic Form; Post-Modern Culture 15 Electronic Journal, 2005. Available online: http://pmc.iath.virginia.edu/issue.105/15.2pold.html (accessed on 14 September 2017).

- Nam, H.Y.; Nitsche, M. Interactive installations as performance: Inspiration for HCI. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Tangible, Embedded and Embodied Interaction, Munich, Germany, 16–19 February 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Norman, D. The Invisible Computer; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Akrich, M.; Latour, B. A Summary of a Convenient Vocabulary for the Semiotics of Human and Nonhuman Assemblies; Bijker, W., Law, J., Eds.; Shaping Technology/Building Society Studies in Sociotecnical Change; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1992; pp. 259–264. [Google Scholar]

- Galloway, A. The Interface Effect; Polity: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ihde, D. Bodies in Technology, Electronic Mediations (Book 5); University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Manovich, L. The Language of New Media; Leonardo Book Series; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sommerer, C.; Mignonneau, L.; King, D. (Eds.) Interface Cultures—Artistic Aspects of Interaction; Transcript Verlag: Bielefeld, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pold, S. The Critical Interface. In Proceedings of the 4th Decennial Conference on Critical Computing: Between Sense and Sensibility, Aarhus, Denmark, 20–24 August 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ishii, H.; Leithinger, D.; Follmer, S.; Zoran, A.; Schoessler, P.; Counts, J. TRANSFORM: Embodiment of “Radical Atoms” at Milano Design Week. In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Seoul, Korea, 18–23 April 2015. [Google Scholar]

- McGoogan, C. The MIT Media Lab is Waging War on Pixels. Wired Magazine. October 2015. Available online: http://www.wired.co.uk/article/hiroshi-ishii-wired-2015 (accessed on 14 September 2017).

- Edmonds, E.A. Human Computer Interaction, Art and Experience. In Interactive Experience in the Digital Age; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 11–23. [Google Scholar]

- Candy, L.; Ferguson, S. (Eds.) Interactive Experience in the Digital Age: Evaluating New 11 Art Practice; Springer Series on Cultural Computing; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, J. What is Artistic Resarch? In Gegenworte 23, Journal Artistic Research; Brandenburgische Akademie der Wissenschaften: Berlin, Germany, 2010; pp. 76–84. [Google Scholar]

- Knowles, J.G.; Cole, A.L. The Handbook of the Arts in Qualitative Research; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- ECU Research Methodologies for the Creative Arts and Humanities. Available online: http://ecu.au.libguides.com/research-methodologies-creative-arts-humanities (accessed on 14 September 2017).

- Dewey, J. Art as Experience; Penguim: New York, NY, USA, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Escudero Andaluz, C. Critical Aspects, Interfight and early works: Codes, Data, Applications, Behaviors, Objects and Protocols. In Proceedings of the First Conference on Interface Politics, Barcelona, Spain, 27–29 April 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gentner, D.; Nielsen, J. The Anti-Mac interface. Mag. Commun. ACM 1996, 39, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youngsuk, L. Hatching scarf: A critical design about anxiety and persuasive computing. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Tangible, Embedded and Embodied Interaction, Munich, Germany, 16–19 February 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hatching Scarf Video. Available online: http://www.youngsuklee.com/Hatching%20scarf.html (accessed on 14 September 2017).

- Borchers, J. A Pattern Approach to Interaction Design; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Tomás, E.; Kaltenbrunner, M. Tangible Scores: Shaping the Inherent Instrument Score. In Proceedings of the NIME 2014, New Interfaces for Musical Expression Conference, London, UK, 30 June–3 July 2014; pp. 609–614. [Google Scholar]

- Tangigle Scores Video. Available online: https://vimeo.com/80558397 (accessed on 14 September 2017).

- Magnusson, T. Of epistemic tools: Musical instruments as cognitive extensions. Organ. Sound 2009, 14, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanc, N. (Ed.) Environmental Humanities and New Materialisms: The Ethics of Decolonizing Nature and Culture. In Proceedings of the 8th Annual Conference on New Materialism. In Proceedings of the 8th Annual Conference on New Materialism, Paris, France, 7–9 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Oulasvirta, A.; Hornbaek, K. HCI Research as Problem-Solving. In Proceedings of the CHI 2016 Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, San Jose, CA, USA, 7–12 May 2016; pp. 4956–4967. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, B. On Actor-Network Theory: A Few Clarifications. Soziale Welt 1996, 47, 369–381. [Google Scholar]

- Danto, A.C. The Transfiguration of the Commonplace: A Philosophy of Art; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, G.; Blythe, M.; Sengers, P. Making by making strange: Defamiliarization and the design of domestic technologies. ACM Trans. Comput. Hum. Interact. 2005, 12, 149–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilde, D.; Vallgårda, A.; Tomico, O. Embodied Design Ideation Methods: Analysing the power of estrangement. In Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Denver, CO, USA, 6–11 May 2017. [Google Scholar]

© 2017 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tomás, E. How The Arts Can Help Tangible Interaction Design: A Critical Re-Orientation. Informatics 2017, 4, 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics4030031

Tomás E. How The Arts Can Help Tangible Interaction Design: A Critical Re-Orientation. Informatics. 2017; 4(3):31. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics4030031

Chicago/Turabian StyleTomás, Enrique. 2017. "How The Arts Can Help Tangible Interaction Design: A Critical Re-Orientation" Informatics 4, no. 3: 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics4030031

APA StyleTomás, E. (2017). How The Arts Can Help Tangible Interaction Design: A Critical Re-Orientation. Informatics, 4(3), 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics4030031