Abstract

Governments increasingly integrate artificial intelligence (AI) into digital public services, and understanding how citizens perceive and respond to these technologies has become essential. This systematic review analyzes 30 empirical studies published from early January 2019 to mid-April 2025, following PRISMA guidelines, to map the current landscape of citizen attitudes toward AI-enabled e-government services. Guided by four research questions, the study examines: (1) the forms of AI implementation most commonly investigated, (2) the attitudinal variables used to assess user perception, (3) key factors influencing attitudes, and (4) concerns and challenges reported by users. The findings reveal that chatbots dominate current implementations, with behavioral intentions and satisfaction serving as the main outcome measures. Perceived usefulness, ease of use, trust, and perceived risk emerge as recurring determinants of positive attitudes. However, widespread concerns related to privacy and interface usability highlight persistent barriers. Overall, the review underscores the need for transparent, citizen-centered AI design and ethical safeguards to enhance acceptance and trust. It concludes that future research should address understudied applications, include vulnerable populations, and explore perceptions across diverse public sector domains.

1. Introduction

In recent years, digital technologies have changed the way governments communicate and provide services to citizens. E-government initiatives aim to improve the accessibility, efficiency, and transparency of public services. A key part of this development is the increasing use of artificial intelligence (AI) in the public sector. Today, governments are increasingly deploying AI tools such as virtual assistants and chatbots to guide citizens through online procedures, including document processing systems for handling applications and licenses, fraud detection in tax and welfare services, predictive models for public health and city planning, and recommender systems that suggest services based on user needs by assisting us in navigating complex administrative procedures by directing them to relevant forms, services, or regulations [1,2,3]. Collectively, these applications are transforming citizen–government interactions by enabling more responsive, data-driven, and cost-effective service delivery.

However, the success of these technologies depends not only on their technical capability but also on whether citizens are willing to use them. Research in the field of e-government has shown that digital services are more likely to succeed when citizens trust them and find them useful and easy to use [4,5,6]. More recently, studies confirm that citizen trust in AI-enabled government systems is influenced by ethical robustness and context-based trust transfer mechanisms [7,8]. The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) both highlight the importance of these factors [9]. Other studies also stress that the clarity of information and the transparency of how systems work are important for building trust and encouraging citizens to adopt these services [10]. In the case of AI-based tools, this is even more important. Users frequently express apprehensions regarding fairness, data privacy, and the use of complex “black-box” algorithms [11]. For this reason, citizen attitudes—shaped by trust, perceived usefulness, risk, digital skills, and beliefs about fairness—have become a key topic in discussions about responsible and inclusive use of AI in government [12].

However, most current research still focuses more on technical or organizational aspects of AI in the public sector than on how citizens evaluate or respond to these technologies. While some literature reviews examine public attitudes, many either analyze AI applications broadly without focusing on digital delivery channels or concentrate on specific tools, such as chatbots. Furthermore, limited attention has been paid to identifying the full range of attitudinal variables and psychological constructs shaping public responses to AI in government.

This paper aims to fill that gap by conducting a systematic literature review of recent empirical studies on citizen attitudes toward AI-based digital government services. Using PRISMA guidelines, we analyzed 30 studies published between 2019 and early 2025. The review is guided by four core research questions:

(RQ1): What implementation forms of AI-enabled services are studied in the current literature?

(RQ2): What are the dependent attitudinal variables examined?

(RQ3): What are the key determinants of citizen attitudes toward AI-enabled government services?

(RQ4): What are the most commonly reported citizen concerns and challenges related to AI-enabled services?

The remainder of this article is structured as follows: Section 2 reviews the existing literature on AI in e-government with a focus on citizen perspectives. Section 3 outlines the methodology used for this systematic review, covering the search strategy and inclusion criteria. Section 4 presents the findings organized around the four key research questions. Section 5 discusses these findings in relation to existing theoretical models and highlights implications for research and practice. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper by summarizing the key points and proposing directions for future investigation.

2. Related Work

While many studies have explored individuals’ attitudes toward e-government services, the relationship between attitudes, public e-services, and AI technology remains understudied. This is due in large part to the novel nature of AI technology. This observation is reinforced by the recent publication dates of the existing literature reviews. Moreover, to date, the literature has predominantly focused on the supply side rather than the demand side. For example, prior studies have emphasized enablers [13], challenges [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21], and benefits [14,16,17,19,21,22] of embedding AI systems into the public sector. In the same vein, past research endeavors have stressed the facilitators, risks, opportunities, and benefits of chatbot adoption in public services [23,24]. Both studies demonstrated that chatbots can enhance efficiency, accessibility, and engagement in public services, but successful adoption depends on factors like technical integration, institutional readiness, and ethical safeguards. So far, [23,24] seem to be the only reviews focusing on a distinct area of AI applications for e-government services.

From a user perspective, we have located just one literature review following a broad approach to AI implementation in public services. Its scope includes both digitally and non-digitally delivered services [25]. The study sought to understand the key factors impacting citizens’ perceptions of government AI adoption. The authors defined the concept of perception as encompassing individuals’ attitudes, beliefs, and their overall evaluation of AI-based public services. The identified factors were grouped into six categories: perceived benefits, perceived concerns, individuals’ and services’ characteristics, trust, and external factors. Regarding public service domains, order and safety emerged as the most frequently investigated areas. User perspectives have also been explored in the context of chatbot use by local governments. The results indicated that individuals’ perceptions are primarily affected by adoption benefits and risks [24].

To the best of our knowledge, the present study represents the first systematic literature review delving into citizens’ attitudes toward AI-enabled digital government services. Unlike the last two studies, which either addressed AI-enabled services broadly or narrowed their scope to a single form of AI implementation (i.e., chatbots), our review adopts a different perspective. It examines citizen-government interactions through all forms of digitally rendered AI services. Through this lens, we aim to gain a comprehensive understanding of how citizens’ attitudes vary across distinct communication channels identified in the literature.

3. Research Method

The present study utilized a systematic review approach, adhering to PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines [26]. Specifically, our research involved four phases: (1) conducting a thorough literature review to identify relevant studies; (2) screening the identified studies; (3) establishing the eligibility criteria; and (4) determining the studies for inclusion.

3.1. Identification

We began our study with a systematic search in Scopus and Web of Science, two of the most widely used databases for literature reviews. The search query we used in both databases is outlined below: ((TS = (“eGovern*” OR “e-govern*” OR “electronic govern*” OR “digital govern*” OR “smart govern*” OR “electronic public services”)) AND TS = (“artificial intelligence” OR “AI” OR “A.I.” OR “chatbots” OR “machine learning” OR “deep learning” OR “ChatGPT”)) AND TS = (“citizen” AND “accep*” OR “behavioral intention” OR “intention” OR “usage continuance” OR “continuance of use” OR “using” OR “adopti*”). To ensure that our analysis reflected the most recent research, we focused exclusively on studies published between January 2019 and our final search date in mid-April 2025. To this end, a comprehensive search strategy was employed, with no restrictions to specific scientific domains, in a deliberate effort to maximize coverage of relevant studies. We set the language criterion to English. The results we obtained were 123 studies from Scopus and 154 from Web of Science. At this point, we focused our evaluation on the titles and abstracts of the studies. If title/abstract relevance was unclear, we reviewed the full text.

To expand our search, we utilized two AI tools (Elicit and Scispace) to automate the literature discovery process. As noted in prior research, this method addresses key limitations of conventional keyword-based searches by reducing time-intensive manual effort [27]. The tools’ natural language processing capabilities also enable complex queries phrased as plain-text questions [28]. The initial inquiries we posed on both platforms pertained to citizens’ perceptions of AI utilization in government portals (i.e., “How do citizens perceive AI use in government portals?”) and their perspectives on the integration of AI technology into public services (i.e., “What are citizens’ views on the integration of AI technology into public services?”). The results obtained were consistent with the maximum results provided by the basic (free) version of each search engine, i.e., 500 and 100 per query on Elicit and Scispace, respectively. As chatbots emerged as a dominant theme in initial results, we ran a third query regarding citizens’ attitudes about the utilization of such technology in public services (i.e., “What are citizens’ attitudes toward the use of chatbots in public services?”). In a manner consistent with the approach previously adopted for Scopus and Web of Science, the titles and abstracts were screened. In cases where the title indicated that the result was not pertinent to our research, we relied on tool-generated summaries (Elicit’s abstract overviews, Scispace’s insights).

The entire search process was carried out from 10 December 2024 to 15 April 2025 and yielded a total of 2077 results for screening.

In the identification process, as delineated above, we omitted studies published before 2019, studies not directly relevant to the topic under investigation, and studies written in languages other than English. In addition, we did not consider studies related to the use of AI technology in the context of smart cities, as smart cities are outside the scope and objectives of this study. The application of these criteria narrowed the results down to 142.

3.2. Screening

The studies that advanced to the screening phase were subjected to a deduplication process. For this purpose, we used the Zotero software (version 7.0.24). A total of 31 duplicates were identified and subsequently removed, thereby reducing the number of records to 111.

3.3. Eligibility

Following the screening phase, we established the eligibility criteria as follows:

Inclusion Criteria

- Studies should have peer-reviewed journal or conference publications.

- Studies should be empirical.

- Studies should focus on examining citizens’ attitudes toward the application of AI technologies in the context of e-government.

- Studies should address the use of AI in services that are solely digitally delivered by governments.

Exclusion Criteria

- Non-open access studies.

- Studies not published in the English language.

- Studies that merely mention the use of AI in e-government, among other state-of-the-art technologies, rather than focusing on it.

- Studies that do not clearly specify how government services are provided.

We retrieved the full text of all potentially qualifying studies and read them thoroughly. We acknowledge that this process may introduce a degree of subjectivity, although efforts such as independent review and predefined criteria were used to minimize bias. We excluded 80 articles for not meeting the eligibility criteria, and a further three articles were excluded due to inability to obtain access. The number of articles that remained was 28. Through the examination of their references, we located an additional relevant study, which increased the number of the selected documents to 29.

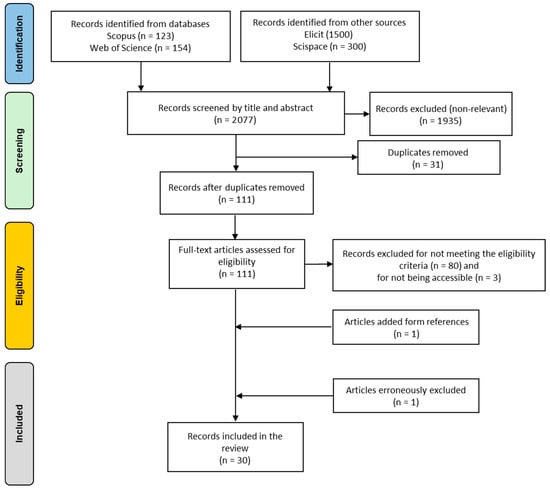

3.4. Inclusion

The concluding phase in our methodological approach involved a cursory review of the full texts of all 109 articles (from an initial 111, after excluding the three inaccessible studies and adding the one retrieved from reference tracking) that potentially fulfilled the inclusion criteria. This step was undertaken to verify that no qualifying studies had been inadvertently omitted and that no ineligible studies had been mistakenly retained. In the course of the process, we identified one erroneously excluded article. As a result, 30 records were ultimately included in this review (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of our review methodology.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

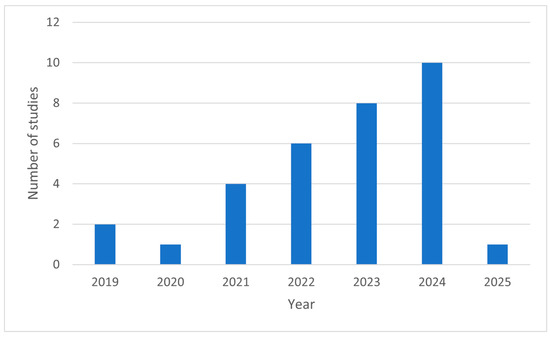

4.1.1. Year of Publication

As illustrated in Figure 2, the number of publications has exhibited a consistent upward trend from 2020 to 2024. This is supported by the growing worldwide focus on incorporating AI technology into government settings over the past few years [29]. Given the limited number of publications (n = 2) in 2019, the decrease from 2019 to 2020 may reflect the nascent stage of research into government AI adoption during that period. As our search covered only the first three and a half months of 2025, just one publication from that year was retrieved.

Figure 2.

Distribution of research papers per year.

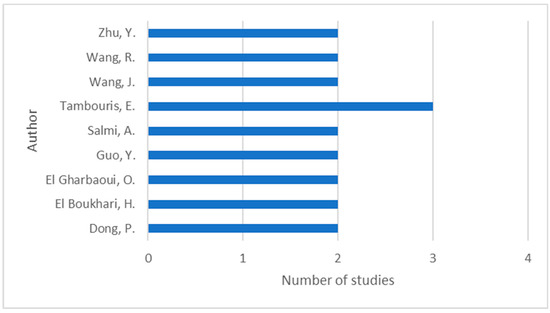

4.1.2. Authors

Figure 3 shows the number of studies by authors with more than one publication. The analysis reveals that Tambouris is the most prolific author, with three publications. The papers included in this review feature a total of 91 authors, representing affiliated institutes across 21 countries.

Figure 3.

Distribution of research papers per author.

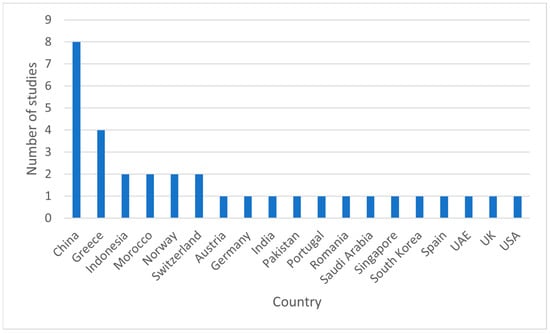

4.1.3. Country Context

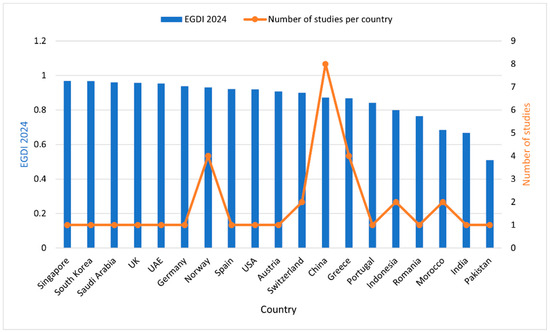

The countries where the studies were conducted (n = 19) are highlighted in Figure 4. In order to present the distribution of papers per country, we set the total number of papers to 33—instead of 30—as one of the studies was cross-national, containing data from four countries (Greece, Singapore, Switzerland, and the USA). China stands out, representing 24% of the total, a position that may be attributed to its top global ranking in both the publication and citation of AI-related research articles [30]. Greece follows at approximately 12%. Indonesia, Morocco, Norway, and Switzerland each represent around 6%. The remaining 39% is distributed equally across 13 other countries.

Figure 4.

Distribution of research papers per country.

Despite the low number of studies and their distribution per country, as depicted in Figure 4, some preliminary regional patterns can still be observed. Studies from Europe were the most numerous and tended to emphasize concerns around privacy, transparency, and data protection, reflecting the influence of regulatory frameworks such as the GDPR. Research from Asia, though smaller in volume, often focused on citizens’ trust in government and optimism toward technological innovation, consistent with the rapid adoption of digital services in the region. Evidence from developing regions such as Africa and Latin America was particularly scarce, but the few available studies pointed to digital divide issues, infrastructural barriers, and low baseline trust in government institutions as key challenges. These contrasts suggest that citizen attitudes toward AI in e-government are shaped not only by the technology itself but also by broader socio-political, cultural, and infrastructural contexts.

Below, we present the relationship between the number of publications per country (research location) and their corresponding 2024 E-Government Development Index (EGDI) scores. The EGDI is a comparative measure of e-government capacity development across United Nations member countries, encompassing three component indicators: scope and quality of online services (OSI), development status of telecommunication infrastructure (TII), and inherent human capital (HCI) [31,32].

Our analysis shows no apparent correlation, as illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

EGDI 2024 score and number of papers per research paper country.

Both countries that rank very high in the EGDI, like Singapore (0.9691) and South Korea (0.9679), and low-ranking ones, like India (0.6678) and Pakistan (0.5096), contributed one publication each. Meanwhile, Greece (0.8674), which ranks close to the average value (0.8594) of the countries in question, produced four. China (0.8718), on the other hand, has the highest number of publications (n = 8), despite its score being relatively close to the average. Norway stands out as the only exception, with a significantly high score (0.9315) and two publications. The absence of a clear positive association may stem from the small number of publications per country, which does not allow for generalizability of the findings. These data are presented for descriptive purposes only and are not intended for statistical inference. It is worth noting that these studies examine not just e-government, but its integration with AI technology. Consequently, the dimension of AI justifies the volume of research papers yielded by China, Norway, and Switzerland, as technologically advanced countries where AI is extensively applied. Although this is not the case for Indonesia and Morocco.

4.1.4. Affiliations

In Table 1, we present author affiliations. To compile this list, we manually reviewed all affiliations. In cases where multiple authors within a single publication belonged to the same institution, we recorded the affiliation only once. For authors with more than one affiliation, we documented each institution. As a whole, our review yielded 47 affiliations across 21 countries. Consistent with the analysis at a country level presented earlier, only the most productive countries are included in the table. China evidently holds a prominent position with seven represented universities, while Tsinghua University (Beijing) is the most frequently occurring institution among all publications (n = 4). Greece follows with two universities, occurring in three and two publications, respectively. Morocco also has two represented universities contributing four equally distributed publications. Norway’s representation includes three universities and one research institution, each appearing in four distinct publications. Finally, Indonesia and Switzerland follow, with three and two institutions, respectively, each appearing in a different publication.

Table 1.

Author affiliations.

4.1.5. Keyword Co-Occurrence

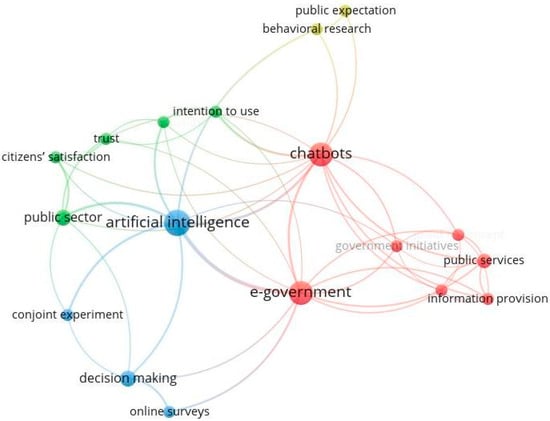

VOSviewer (Visualization of Similarities Viewer, version 1.6.20) is a freely available software tool widely used in academic research. Utilizing text-mining analysis, it generates and visualizes scientific network maps based on co-occurrence matrices [33]. Although VOSviewer is primarily designed for bibliometric analysis rather than systematic literature reviews, we employed it because it offers valuable insights into keyword co-occurrence by visualizing them in clustered networks (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Keyword co-occurrence network generated by VOSviewer (Version 1.6.20).

The analysis showed that AI (n = 15), e-government and chatbots (each with n = 11) are the most frequently occurring keywords, grouped into four clusters: red reflects technology and government (e.g., chatbots, e-government), blue includes AI and research methods (conjoint experiment and online surveys), green relates to citizens’ views (e.g., intention to use, satisfaction), and light green covers behavioral research and public expectation.

4.2. Study Overview

An overview of the studies is presented in Table 2, detailing the study references, titles, publication types, journals or conference proceedings where each study was published, and research objectives. Approximately half of the studies were published in peer-reviewed journals, while the remaining half were presented at international conferences. The wide variety of journals and conferences underscores the multidisciplinary nature of AI research in the field of government services. It encompasses fields such as computer science, medical science, economics, and public administration.

Table 2.

Overview of the research papers.

4.2.1. Analysis Approach

This subsection analyzes three key aspects of the reviewed literature: theoretical frameworks, methodological approaches, and statistical techniques (Table 3). We first examine the theoretical foundations employed across studies, then assess methodological transparency through questionnaire availability, and, finally, identify the most prevalent statistical methods in the research.

Table 3.

Study methodologies overview.

The methods used were primarily quantitative (n = 25), with mixed methods (n = 4), and one qualitative approach comprising the remaining studies. Most quantitative studies utilized survey research methods (n = 21), with a smaller number employing experimental techniques (n = 4). Three of the mixed-methods studies used experimental approaches [35,36,37], while the fourth conducted cross-platform digital discourse analysis [53]. In the qualitative study, the data were collected with semi-structured interviews [47].

A variety of theoretical models were used; nevertheless, TAM was the most widely applied (n = 8). This is in line with our review’s focus on the attitude aspects of interactions between citizens and AI in e-government settings. The IS Success Theory was the second most common framework identified (n = 4), followed by UTAUT/UTAUT2 (n = 3). Frameworks were proposed by the authors in eight studies, whilst in four studies, the theoretical basis was not specified. More than one framework was utilized in three studies [39,58,59]. It is important to highlight that one study made a significant contribution to the existing literature by introducing a novel theory [57]. When it comes to data collection methods, questionnaires were fully documented in fewer than half of the studies (n = 13), most commonly in appendices, rather than in the methodology. One study incorporated only partial items within its main text [34]. Finally, PLS-SEM (n = 10) and descriptive statistics (n = 7) were the most frequently used statistical analysis approaches, followed by regression-based models (n = 6).

4.2.2. Study Quality Assessment

To ensure rigor and transparency, we assessed the quality of the included studies for methodological soundness and reporting clarity. We adopted a simplified checklist approach inspired by the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) guidelines [64] and aligned with the PRISMA methodology [26]. Two authors independently assessed each study, and any disagreements were resolved through discussion and consensus. Five key quality criteria were considered:

- Clear Research Objectives: whether the study explicitly states its aims or research questions. Transparent objectives are necessary to determine the focus and relevance of the study.

- Methodology Transparency: the extent to which the study adequately describes its research design, data collection procedures, and analytical approach. Transparent reporting enables replication and enhances reliability.

- Sampling Adequacy: The representativeness and appropriateness of the sampling strategy, including sample size justification. Appropriate sampling strengthens the validity and generalizability of findings.

- Validity/Reliability/Trustworthiness of Measures: Whether the study reports reliability checks (e.g., Cronbach’s alpha) and/or validity measures (construct, content, or convergent validity). This criterion ensures that the instruments used to measure constructs produce consistent and accurate results. In the case of qualitative studies, the “Validity/Reliability” column was interpreted as “Trustworthiness” referring to whether the authors described steps ensuring credibility, dependability, transferability, or confirmability [65].

- Relevance to the Review Scope: The degree to which the study directly examines citizen attitudes toward AI-enabled e-government services. It ensures inclusion of studies aligned with the objectives of this review.

Table 4 depicts the assessment of each included study against each predefined criterion. More specifically, each study was rated using ✔, △, or ✖ for each criterion, assigned a cumulative score, and classified as either high quality (meeting at least four out of five criteria), medium quality (meeting two to three criteria), or low quality (meeting fewer than two criteria). Out of the 30 studies, 11 (37%) were classified as high quality and 19 (63%) as medium quality, while no study was rated as low quality. The review retained all studies to ensure comprehensive coverage, but findings from medium-quality studies are interpreted with caution.

Table 4.

Study quality assessment.

4.3. Synthesis of Findings

4.3.1. AI Implementation Forms

For the purposes of this review, “AI implementation forms” refer to the various forms of AI that serve as theoretical foundations in the selected literature. These approaches are organized into three primary categories: (1) Chatbots and Virtual Assistants, (2) AI-Enabled E-Services, and (3) Other Forms (Table 5).

Table 5.

Categories of AI implementation forms.

It is evident that chatbots are a prominent feature of the selected studies. They are presented as a means of providing personalized information [36,37,42], empowering citizens [44], enhancing public engagement [45,57,61], addressing the public sector resources shortage [46,47], expediting service delivery [54], enabling government digital transformation [55], and improving accessibility to public services [58]. Some papers propose innovations such as technological architectures [36,39], novel solutions [37,41], and technological integrations aiming at enhancing functionality [42]. Others base their research on the analysis of existing chatbot systems [40,44,45,46,47,49,59,61]. The remaining studies concerning conversational agents address them as a general concept rather than specific implementations [54,55,57,58,62]. Additionally, chatbots are examined at different levels of governance, including both national and local (municipal/provincial) levels [40,47,49,59], demonstrating their ability to adapt and be used in various settings. Overall, chatbots designed for various purposes and capable of performing diverse tasks are investigated. Examples include providing the cost of filing for divorce [36], assisting with passport applications [37,42], offering mental health advice [40,46], and delivering policy consultation services [57,58]. In contrast, virtual agents or virtual assistants are addressed in two studies, although the term is used interchangeably with chatbots [34,38]. Similarly, several other studies treat chatbots and virtual agents as synonymous terms [39,40,44,45,46,61]. Notably, one study distinguishes chatbots into two categories: simpler chatbots that use preprogrammed rules and AI-powered chatbots that use Large Language Models (LLMs) to automatically provide responses using Natural Language Processing (NLP) [62]. An LLM is a type of artificial intelligence model based on deep neural networks that is trained on massive corpora of text data to learn statistical patterns of language. By leveraging billions of parameters, LLMs are able to generate coherent, contextually relevant text, perform reasoning tasks, and adapt to a wide range of NLP applications without task-specific training [66].

The second category pertains to AI-driven digital government services. The studies in this group do not focus on AI-specific tools, but rather on AI technology in its wider sense. This category comprises a significantly smaller number of publications (n = 7). Here, publications can be divided into those focusing on specific e-services and those discussing e-services in a broader manner. Targeted e-services are addressed in three out of the seven studies, covering areas such as digital voting [43], issuing national entry visas and parking licenses [48], and tax filing [52]. The remaining studies—[50,51,60,63]—do not focus on specific digital services. Instead, they discuss e-services more generally.

Other types of AI implementation were also identified. Although they involve distinct AI technologies and given their limited representation in the reviewed literature, they were combined into a single category. These include a proposed system combining human and AI-powered machine capabilities for integration into e-government portals to streamline completion of e-services [35]; the ChatGPT model examined for integration with government services [53]; and recommender systems aiming at providing tailored interactions with public services [56]. The limited attention these innovations have received may be attributed to two factors: their emerging nature and the multifaceted challenges associated with the adoption of such advanced technologies by the public sector [67,68,69,70].

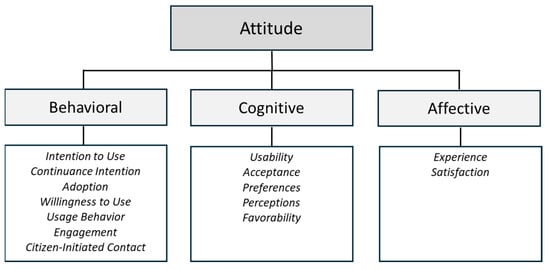

4.3.2. Definition and Components of Attitude

In this subsection, we discuss the different aspects of citizens’ attitudes explored in the extant literature. The Cambridge Dictionary defines attitude as “a feeling or opinion about something or someone, or a way of behaving that is caused by this” [71]. The definition clearly shows that attitude constitutes a multidimensional concept encompassing feelings, opinions, and behaviors as inherent characteristics. That is further supported by the ABC model [72], which proposes that attitude consists of three components: affective, behavioral, and cognitive. The ABC Model of Attitudes has been extensively applied in consumer behavior research, primarily through its integration into the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA). The affective component refers to individuals’ emotions, the behavioral component relates to their actions, and the cognitive component pertains to their thoughts and beliefs. In concern to the behavioral dimension, it is essential to point out that two of the reviewed studies examined behavioral outcomes [51,54], while the third assessed behavioral intentions, despite the fact that usage behavior was the dependent variable [39]. This might be because measurement of actual behaviors necessitates non-probabilistic sampling, which may introduce research bias. After all, information systems adoption models (e.g., TAM, UTAUT, TRA, and TPB) postulate that intentions are strong predictors of subsequent behaviors [73]. Table 6 shows the distribution of the selected articles across the three aspects of attitude.

Table 6.

Components of Attitude investigated in the reviewed literature.

Our analysis reveals that the literature focuses predominantly on the behavioral component of attitude (12 exclusive references), followed by the cognitive (8 references) and affective dimensions (7 exclusive references). Three additional studies fall into both behavioral and affective categories [44,46,54], and are not included in the exclusive counts above.

4.3.3. Attitudinal Dependent Variables

Studies aiming at predicting individuals’ behavior examine the attitudinal factors of intentions [34,36,37,44,46,47,50], adoption [35], willingness to use [38,45], usage behavior [39,51,54], engagement [61], and the likelihood of citizens to initiate contact with the government [62]. Research on individuals’ thoughts and beliefs investigates usability [42], acceptance [43,48,53,60], preferences [49], perceptions [52], and favorability [58]. Exploration of citizens’ emotions includes examination of satisfaction [40,41,44,46,54,55,56,57,63], and experience [40,59] (Figure 7). Given the empirical nature of the articles, these constructs serve as dependent variables in their respective theoretical models. In studies where more than one response variable was examined, we selected only those pertaining to our research scope. Our examination revealed 14 distinct dependent variables, listed in Table A1 of Appendix A.

Figure 7.

Components of attitude.

It is important to note that some of these concepts are nuanced and have been defined in different ways within the context of information systems. For example, acceptance has been defined as “the positive decision to use an innovation.” [74]. On the other hand, it has also been described “as the demonstrable willingness within a user group to employ information technology for the tasks it is designed to support” [75]. According to this rationale, willingness to use is not a distinct characteristic of attitude but inherent in acceptance. Moreover, adoption has been conceptualized as “the use or acceptance of a new technology, or new product.” [76]. This interpretation suggests that adoption encompasses acceptance. Furthermore, we observed that in some of the reviewed studies, concepts were used as synonyms. For instance, acceptance and intention to use were used interchangeably in [43], and this is also the case with acceptance and attitude in [53]. Nevertheless, we treated them as distinct variables to maintain consistency with the theoretical frameworks of their respective studies.

4.3.4. Key Determinants of Citizen Attitudes Towards AI-Based E-Government Services

As governments around the world increasingly employ AI technology, there is a growing need to understand citizens’ views. Scholars have examined the effect of multiple factors on attitudinal dependent variables. Below, we present these factors by dependent variable and AI implementation form.

Factors Influencing Citizens’ Behavior

Research shows that individuals are more prone to using virtual assistants when their autonomy and decision-making capacity are low [34]. Perceived ease of use (PEU) and perceived usefulness (PU) hold a prominent position among the determinants of citizen intention to use government chatbots. Proof-of-concept chatbots in experimental studies were overall positively evaluated by participants who found them effortless to use, useful in obtaining information, and time-saving [36,37]. Citizens’ intention to use chatbots is strengthened by the satisfaction gained from using them [44], as well as by their trust in both technology itself and public institutions [47]. Regarding citizens’ intention to continue using AI-enabled services, it is primarily driven by usefulness, service reliability, and security of technology [50]. Contrary to what might be expected, the study in [46] found that voice interaction—generally considered a positive attribute of chatbots—along with the feeling of enjoyment and the COVID-19 pandemic did not exert a significant impact on the continuance intention of mental health chatbots usage. Another interesting result of this study is that the ability of a chatbot to provide tailored information only weakly influences continuance intention. This is not in line with the results reported in [36,37] nor with the previous literature. The authors attributed this inconsistency to the potential inappropriateness of the applied theoretical model for the objectives of their research.

Adoption was investigated in a single experimental study aiming to establish whether a human–machine collaborative system designed to be integrated into government portals could boost adoption of digital services. The research team targeted specific population groups, including older adults and individuals with disabilities. The results indicated that the system was positively rated by participants as it enhanced accessibility [35]. With regard to willingness to use voice assistants, interest is greater among citizens embracing emerging technologies. That said, individuals remain doubtful about using them for complex digital services [38]. Similar to the intention to use government chatbots, willingness to use AI-powered public services is largely influenced by PU [45]. Usage behavior in its literal sense is assessed in two studies [51,54], while the remaining study evaluates usage intention rather than actual use [39]. Actual usage has been studied in relation to smart government encompassing AI technology [51] and chatbots [54]. The findings suggest that the utilization of smart government technology is positively influenced by satisfaction, trust in government, and perceived cost [51]. Furthermore, behavioral intention was found to be a good predictor of chatbot usage [54]. Meanwhile, citizens’ intention to utilize chatbots to communicate with the government is contingent upon trust in technology and perceived risk [39]. Next, citizen engagement in decision-making can be enhanced through the use of chatbots [61]. Notably, empirical evidence indicates that citizens are more likely to initiate contact with the government when responses are human rather than AI-generated. This likelihood further decreases with rule-driven AI systems, declining even more when learning-driven AI is utilized [62]. The authors connected this behavior to citizens’ reluctance to use AI technology when direct communication with civil servants remains an option.

Factors Influencing Citizens’ Cognitive Beliefs

Acceptance is the predominant variable explored in this category (n = 4). A cross-cultural survey conducted in four countries (Greece, Singapore, Switzerland, and the USA) highlighted the significance of PU and PEU in relation to the acceptance of an AI-based voting system [43]. Accuracy and reduced cost also proved to be pivotal factors in the acceptance of AI-powered decision-making in e-government [48]. The degree of acceptance of ChatGPT’s integration into digital governance was assessed through user-generated data collected from platforms such as YouTube and Zhihu. The analysis indicates that trust in both government and technology, along with perceived risk, are determinants of citizen acceptance [53]. Social influence is also recognized as a key factor in the acceptance of AI use in the public sector [60]. Similar to the approach followed in [36,37], usability was experimentally tested through a prototype chatbot integrating knowledge graphs. Results from ΤAΜ and SUS-based questionnaires validated the chatbots’ ease of use, effectiveness, and usefulness [42]. Regarding preferences, users favor interacting with chatbots over other e-government services when social characteristics like emotional intelligence and proactivity (e.g., ability to propose subsequent inquiries) are integrated into chatbots. The same study posits that informal and friendly chatbot language is more appealing to citizens [49]. Public perceptions of AI-powered income tax filing systems are positively influenced by the systems’ accuracy, reduced error risk, and time savings [52]. Finally, cognitive beliefs are also explored through the factor of favorability. For e-service delivery, citizens favor chatbots with characteristics like appealing interfaces, ease of use, usefulness, and security. Attributes like natural-feeling dialogue and high system quality do not significantly impact their favorability. Conversely, for policy consultation purposes, system quality and quality of information are considered of great importance [58].

Factors Influencing Citizens’ Affective Responses

Among the various factors shaping citizens’ attitudes regarding government AI use, satisfaction has received the most attention (n = 9). Higher satisfaction levels are associated with citizens opting for automated solutions [41], their sense of autonomy, and their perception of chatbots’ benefits [44]. In contrast, personalization and user eagerness to acquire knowledge through engagement demonstrate only a modest positive correlation with satisfaction [46]. Intention to use chatbots, usage behavior [54], and high degrees of chatbots’ and recommender systems’ use lead to greater satisfaction levels as well. Although trust in these systems plays a positive role in raising satisfaction levels, the most significant aspect is its moderating effect in the relationship between usage behavior and satisfaction [55,56]. Citizens’ expectations from the government (e.g., accountability, transparency, interactivity) and positive emotional perceptions further enhance the satisfaction experienced by chatbot users [57]. Compared to transparency and trust in AI services, service accuracy exerts the strongest influence on perceived service value, thereby contributing to higher satisfaction levels. Furthermore, human–AI collaboration proves particularly significant in services where transparency and trust are more crucial than service accuracy [63]. Experience was assessed in relation to the use of mental health chatbots during the coronavirus pandemic. The findings revealed that a chatbot’s ability to provide tailored services, users’ desire to gain knowledge through interaction, and the pandemic’s unusual circumstances conjointly contributed to a positive user experience [40]. Beyond these factors, perceived friendliness and competence of chatbots are also identified as drivers of experience enhancement [59].

The analysis reveals that PU and PEU dominate among the key factors shaping citizens’ attitudes toward AI-driven government services. This aligns with the frequent adoption of TAM and UTAUT as theoretical frameworks in both the reviewed studies and the wider literature on citizens’ attitudes toward information systems. By the same token, trust—particularly trust in government and technology—is identified as a pivotal factor. Trust, as a construct, is widely employed in empirical studies exploring attitudes in relation to nascent technologies. It is considered an essential precondition, particularly for potential users, to embrace the technology in question and rely on its provider. The literature also focuses on the significance of the perceived risk, the provision of personalized services, and the usage frequency of AI-driven services. Security, accuracy, cost reduction, time savings, and chatbots’ human attributes are also commonly investigated, albeit usually less influential. Last, socio-demographic factors appear to be among the least impactful determinants.

The research variables (independent, control, mediating, and moderating) deployed in the reviewed literature, along with their definitions/explanations, are documented in Table A2 of Appendix A.

4.3.5. Citizens’ Concerns and Challenges in AI-Enabled Services

Inexperience is often closely associated with hesitance stemming from doubt and uncertainty. Thus, it is common for individuals to question the trustworthiness and reliability of novel technologies, especially during initial interactions. Several factors inducing skepticism were identified. To begin with, ethical concerns, particularly the lack of data privacy and privacy protection measures, often discourage citizens from using AI in government interactions [38,45,48,52]. Concerns intensify when AI systems operate with high levels of autonomy, as this can generate a perceived loss of control [34]. This feeling becomes more intense when AI technology is utilized for decision-making processes [34,48] or when users are required to share higher amounts of private data [45]. Interestingly, though, citizens are sometimes willing to disclose personal information at the expense of their privacy protection, as long as they perceive AI technology as useful, validating the so-called “privacy paradox” [45]. At the same time, the sense of unfamiliarity with digital assistants constitutes another source of concern [30].

Apart from issues evoking skepticism, we also discovered challenges linked to the practical use of AI systems. These challenges are largely derived from interface designs and limitations of chatbots. They were primarily detected in experimental studies where participants described their experiences after testing them. These comments provide valuable insights into potential downsides of chatbots, even if reported by a minority of participants. For example, 7 out of 19 evaluators of a chatbot designed to provide tailored services reported that, overall, they were disappointed by its performance, while 2 found it ineffective [36]. After interacting with a chatbot facilitating the acquisition of a passport, 17 out of 53 participants encountered difficulties conveying their inquiries to the chatbot due to its inability to comprehend input texts. At the same time, 12 users complained about extensive replies and the absence of an option to connect with a human representative [37]. In a trial assessing citizens’ intention to use a municipality chatbot, there were respondents who perceived the use of the chatbot as unnecessary, a result also seen in [36], whilst most reported that the chatbot failed to address complex inquiries, consistent with [38]. Another point made by users was related to chatbot visibility. In particular, placing it at the bottom right corner of the screen instead of the top would discourage them from engaging with it. Meanwhile, a few participants noted the difficulty of formulating a prompt that would be understood by the chatbot [47]. Beyond usability, barriers related to interaction were also found. An online survey exploring citizens’ willingness to use voice assistants revealed that impersonal interaction and the lack of features facilitating accessibility for people with disabilities were reasons for negative evaluations [38]. Regarding studies on AI-enabled services, we identified only one challenge: respondents faced difficulty in understanding AI algorithms when using AI-powered tax-filing systems [52]. Finally, in the category of other forms of AI implementation, we located challenges in a single study assessing the adoption of a hybrid intelligence system integrated into a portal mirroring an existing e-government platform. Specifically, most participants complained about the excessive length and complexity of the e-services presented during the experiment. They also criticized the large volume of information provided and reported difficulty in understanding the website’s phrasing [35]. While these challenges may not reflect the views of the majority of participants or respondents, they should still be considered when designing AI-powered systems for e-government services.

Taken together, these challenges and concerns represent significant barriers to the acceptance of AI technology in the public sector. Building citizen trust requires more than technical improvements; it demands robust regulatory frameworks and governance mechanisms. Section 5.2 elaborates on how effective AI governance can alleviate these obstacles.

4.3.6. Limitations and Future Recommendations of the Reviewed Studies

Table 7 presents the limitations and suggested future research directions identified in the literature.

Table 7.

Limitations and future recommendations of the reviewed studies.

The reviewed studies identified the prevalence of methodological limitations primarily involving sampling issues [34,40,42,43,44,46,51,52,55,56,58,62,63] and data collection and evaluation problems [34,43,45,50,53,57,58,59,63]. The most common theoretical implications concern potential insufficiency of the model(s) employed [39,46,59], and non-consideration of important constructs [49,50,54]. No practical limitations were found; however, three studies did not explicitly report any constraints [38,41,60].

In addition to the limitations cited by the authors, our review yielded general conclusions about weaknesses in the literature. Sample-wise, respondents and experimental subjects were mostly young (18–30 years old) and moderately to highly educated, both suggesting a high likelihood of digital literacy. Technological familiarity is closely associated with adoption willingness [77]; hence, tech-savvy individuals are more susceptible to engaging with novel technologies. Moreover, the widespread use of web-based data collection methods, primarily online questionnaires followed by online experiments, leads to the underrepresentation of certain population segments. These include individuals with no or limited internet access, older adults, people with disabilities, and often non-English speakers. Research has shown that web surveys entail a high risk of coverage error [78] and that online and offline households significantly differ in terms of demographic characteristics [79]. All the same, we must acknowledge that both AI and digital government are heavily contingent on web-based systems, making online sampling and data sourcing methods an almost unavoidable constraint. In terms of methodology, only a limited number of studies explored mediating and moderating variables [45,48,50,55,56,58,59,63]. Incorporating moderating and mediating effects into academic research enables a more profound understanding of construct relationships [80].

Another shortcoming we found is that there are several attitude-forming factors that prior studies did not touch upon. Unequivocally, technology, besides being beneficial, has a harmful facet as well, first and foremost because of improper human use. In this context, apart from data privacy and security issues, concerns are raised about the adverse societal implications of AI. Frequently expressed apprehensions include job displacement risks and potential exacerbation of discrimination and inequality. As these concerns hold equally true for AI use in digital government, one would expect them to be discussed in the reviewed studies. We must also point out that personality traits (e.g., agreeableness, conscientiousness, extraversion) are overlooked despite substantial evidence of their effect on technology acceptance [81,82,83,84]. Lastly, the role of government as a watchdog for responsible and ethical use of AI in the public sector remains underexplored. Although trust in government has received scholarly attention [47,51,53], the impact of government regulations and legal frameworks—their presence or absence—as an attitude-forming variable, is poorly addressed. This gap has significant implications for understanding citizen trust and, by extension, attitude.

Regarding future recommendations, we paid particular attention to proposals offering specific directions, avoiding as much as possible reporting those simply stating the opposite of limitations. Notably, [34] acknowledges the need to investigate civil servants’ perceptions about AI implementations in government. Building on this recommendation, we argue that a comparative study mapping similarities and differences between citizens’ and public officials’ attitudes, challenges, and concerns could substantially enrich the literature. For the recommendation to grant chatbots access to users’ private data to deliver more efficient, tailored services [37], we suggest combining it with increased transparency and robust legal frameworks to mitigate privacy concerns. Expanding on [56], calling for evaluation of recommender systems’ impartiality and fairness, we argue that integrating user feedback is fundamental. User feedback should serve as a guide for both AI systems developers and governments in designing and deploying recommender systems and bots in web portals. Since government recommender systems, chatbots, and especially generative AI systems have access to sensitive information, post-adoption evaluation for potential biases and discrimination is a critical prerequisite for building public trust.

We further recommend investigating citizen attitudes toward understudied AI services, such as ChatGPT, voice-to-form systems, document verification tools, user identification applications, etc. Future work should also address ethical dimensions by examining, for instance, how regulatory frameworks (e.g., EU AI Act) shape citizen trust, and consequently attitudes. Finally, it would be worthwhile to assess potential relationships between attitudes toward e-government services and AI-based e-government services.

5. Discussion

5.1. Summary of Core Findings

Our study highlights key aspects of the relationship between citizen attitudes and government AI services. Based on our research questions, our findings are summarized as follows: Regarding RQ1 (What implementation forms of AI-enabled services are studied in the current literature?), our research revealed that chatbots are the main focus. Considering that the private sector has long adopted chatbots through web portals, it can be argued that the public is more familiar with them compared to other AI tools. This assumption is further supported by [85], which shows that chatbots are among the most popular types of AI used in governments globally. Between 2018 and 2022, the number of UN member countries providing chatbot functionality in their national portals experienced significant growth, rising by approximately 146% [86]. Unlike chatbots, advanced systems such as generative AI have become popular only recently and thus remain understudied.

To address RQ2 (What are the dependent attitudinal variables examined?), we first classified them into three categories—behavioral, cognitive, and affective—based on the ABC model. Our findings show that overall, attitudes are mostly measured through behavioral and affective outcome variables, particularly through behavioral intentions (n = 9) and satisfaction (n = 8), respectively. This focus on intentions aligns with theoretical frameworks often used in attitude research, such as the TPB, TRA, TAM, and UTAUT, where intention is viewed as a direct antecedent of behavior. By the same token, the prominence of satisfaction underscores its crucial role as an attitude-shaping factor. Drawing from the IS Success Model, satisfaction emerges as a key factor connecting the quality of a system to positive citizen attitudes and intentions to use the system [87].

About RQ3 (What are the key determinants of citizen attitudes toward AI-enabled government services?), PU and PEU stand out as the most prominent factors fostering positive attitudes. The predictive power of PU and PEU has been widely established in both the context of digital government and AI. For example, [88] found that PU and PEU explained more than half of the variance in users’ continuance intention of e-government services. Likewise, studies on consumers’ intention to use autonomous vehicles [89] and to shop at AI-powered automated retail stores [90] identified PU and PEU, respectively, as the most influential factors. Another critical finding is that trust in both the technology and the institutions deploying it operates as an amplifying factor of the PU and PEU effect [23]. This suggests that while citizens are primarily motivated by how useful and easy to use a service is, trust mitigates perceived risk [91].

Regarding RQ4 (What are the most commonly reported citizen concerns and challenges related to AI-enabled services?), our results reveal two main dimensions. First, data privacy is the most frequently cited issue among users, contributing to negative attitudes. The importance of protecting data and privacy in AI applications has been widely acknowledged not only in scholarly research but also by international organizations and the EU. An example is the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Artificial Intelligence [92], which stresses the need for AI stakeholders to respect human privacy. Another example is the EU Ethics Guidelines for Trustworthy AI [93], which call, among other things, for processing data in a lawful manner, protecting data subjects’ privacy. Second, practical challenges result mainly from chatbots’ lack of competence and ineffective interface design. For instance, experimental participants reported that the tested chatbots had limited capacity to understand prompts, generated overly long responses, failed to handle complex tasks, and lacked accessibility features. Prior studies have also identified chatbots’ limited prompt comprehension as one of the most common reasons for failure, leading to user frustration and frequent abandonment of interactions [94,95,96,97].

5.2. AI Governance in the Public Sector

Citizen concerns and challenges [35,36,37,38,45,48,52], underscore the importance of governance frameworks. Effective AI governance encompasses a set of regulations, procedures, and technological mechanisms designed to ensure that the development and deployment of AI technologies align with democratic values, the rule of law, and citizens’ well-being [98].

Transparency and accountability are central to this governance. For example, chatbots’ limited ability to interpret prompts [37] and users’ difficulty in understanding “black box” algorithms [52] can raise trust issues [99]. Citizens may question the reliability of the technology and public institutions, which may discourage them from using AI-enabled services [99]. Transparency is about governments providing clear information on the purpose of these systems, how they operate, and the data they rely on [100]. Importantly, transparency also means guaranteeing that users know whenever they are engaging with AI [101]. Accountability strengthens transparency. In fact, one cannot exist without the other [101]. Citizen preference for human interaction over AI [37] highlights the need for accountability. Accountability ensures that mistakes and biases are addressed efficiently. Knowing that a human being will be held responsible for an erroneous AI-generated decision or misjudgment contributes to building citizen trust. However, accountability is not limited to decision-making; it spans the entire life cycle of AI systems [99]: design, development, and deployment [102]. Governments should establish due diligence mechanisms, implement audit systems, and employ human oversight to ensure accountability [99]. Explainability is also a key component of AI governance. A lack of explainability prevents citizens from having confidence in AI systems [103], especially when decisions affect their welfare, such as determining eligibility for social benefits. Beyond understanding the rationale of an AI system’s decision, citizens also have the right to know why AI is employed in a given instance. To this end, governments are obliged to provide interpretable explanations as a necessary precondition for fairness and non-discrimination [104]. Furthermore, principles such as privacy, security, and social benefit are fundamental to fostering public trust as a key determinant of positive citizen attitudes [105]. For these principles to be applied lawfully and ethically, legal frameworks have been established, and initiatives have been taken around the world. The AI Act [105] constitutes the first global attempt at introducing a horizontal regulatory framework for AI. Its objective is to ensure that AI technologies are safe, transparent, and aligned with EU values. Complementary to this, the EU Ethics Guidelines for Trustworthy AI [93] provide a framework for promoting lawful, ethical, and robust development and deployment of AI technologies. Globally, the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Artificial Intelligence [92] is the first international standard for AI governance. Some of its core principles are transparency, explainability, accountability, security, and safety. Similarly, the UNESCO Recommendation on the Ethics of Artificial Intelligence [99] provides guidelines for countries to create their own legal frameworks. Finally, initiatives like the Global Partnership on Artificial Intelligence (GPAI) [106] work to ensure that AI systems are designed responsibly and for the benefit of humanity. In summary, fostering positive attitudes toward AI-enabled services necessitates a foundation of ethical governance. Standards like transparency, accountability, and explainability are essential to demonstrate that AI operates fairly and reliably. When governments apply these values, they enhance public trust. This means that AI does not just work properly, but citizens also perceive it as a dependable and useful tool.

5.3. Theoretical Integration

As discussed in Section 4.3 (Synthesis of Findings), several of the studies employed established theoretical frameworks such as the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT), and the Information Systems Success Model (IS Success Model). The present review indicated that these models provide useful but partial explanations for the observed variations in results.

Findings linked to TAM consistently emphasized the importance of perceived usefulness and ease of use, which appeared as common predictors of citizen attitudes across diverse contexts. UTAUT added explanatory depth by highlighting the role of social influence and facilitating conditions, factors that appeared particularly salient in developing regions where infrastructural barriers are more pronounced. Meanwhile, the IS Success Model was useful in accounting for variations in system quality, information quality, and service quality, which were shown to affect trust and satisfaction with AI-enabled services.

At the same time, existing models only partially capture the unique features of AI in e-government. Critical factors such as algorithmic transparency, fairness, explainability, and accountability are not fully addressed within traditional acceptance frameworks. This points to the need for theoretical extension and integration, combining established technology acceptance and IS models with concepts from AI ethics and governance. Such integration would enable a more comprehensive understanding of citizen attitudes and provide a conceptual basis for future empirical research.

5.4. Limitations and Future Recommendations

This review is subject to several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. First, it focuses exclusively on digitally delivered AI-based government services, particularly those available through the web and mobile platforms. Future studies could broaden the scope of research, encompassing, for example, hybrid services and self-service terminals. Second, our study does not examine back-end administrative AI applications. To comprehend and expand our understanding of citizen attitudes, future research should examine AI-enabled services that are not directly seen by citizens, like automated decision-making and fraud detection. In a similar manner, research including smart cities, where both digital and non-digital AI-based services are provided, would produce valuable insights. Third, our research does not focus on specific public sector domains. It would be interesting if subsequent studies explored citizen attitudes in relation to the use of AI in education, health, law enforcement, other governmental functions, etc. Fourth, this review may be affected by publication bias. By limiting our search to two databases (Scopus and Web of Science), non-indexed studies might have been missed. Although we extended our search using Elicit and SciSpace, the risk of bias could not have been eliminated. Furthermore, while all studies were peer-reviewed, not all selected studies were published in top-tier journals or presented at highly ranked conferences. Finally, the exclusion of non-English studies and gray literature may have also introduced publication bias.

While this review aimed to provide a comprehensive and systematic synthesis, several potential threats to validity should be acknowledged. Regarding consistency, we applied predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria, a transparent search strategy, and double coding for study selection to ensure reliability. Nevertheless, the heterogeneity of study designs and national contexts inevitably introduces variability, which may affect the comparability of results. In terms of replicability, the search process, databases, and quality assessment checklist were documented in detail, yet the reliance on Scopus as the primary database and the temporal cutoff of the search mean that some relevant studies may not have been captured. The generalizability of the findings remains limited: the overall evidence base is modest in size, with most countries contributing only one or two studies, and entire regions such as Africa being underrepresented. Another limitation concerns the potential for subjectivity in the full-text screening process. Although inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied systematically, the assessment of fit to the review’s scope inevitably involved researcher judgment. This potential bias was mitigated through transparent criteria and cross-checking, but it cannot be fully eliminated. For these reasons, our conclusions should be interpreted as indicative, and further research across diverse contexts is required to strengthen the evidence base.

6. Conclusions

Artificial intelligence holds great potential to transform e-government services. While the introduction of traditional e-government services signified the beginning of a new era, AI is poised to revolutionize the way these services are delivered. The responsibility for this transformation lies with developers and governments. Creating citizen-centered AI systems is critical to cultivating public trust and engagement. Yet, whether this transformation succeeds is up to citizens to determine. Thus, understanding their perceptions, preferences, intentions, and behaviors sets the foundation for harnessing the merits of AI.

Beyond the recognized significance of designing and embedding easy-to-use, reliable, and transparent AI services into digital government, our research has uncovered equally important yet less apparent implications. For policymakers, raising citizens’ awareness of AI’s benefits can strengthen its perceived utility. At the same time, informing the public about potential risks, as well as ways to avoid them, can make them feel less intimidated. In the same vein, the gradual introduction of tools other than chatbots may foster greater familiarity. For developers, co-creating AI services with citizens can help them better understand and meet citizen needs, thereby boosting confidence. Finally, public institutions should ensure that humans remain in the loop and actively promote civil servants’ digital literacy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.R. and S.B.; methodology, M.R., S.B. and I.S.; formal analysis, I.S.; investigation, I.S. and M.R.; data curation, I.S.; writing—original draft preparation, I.S. and M.R.; writing—review and editing, I.S. and M.R.; visualization, I.S.; supervision, M.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The publication fees of this manuscript have been financed by the Research Council of the University of Patras.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TAM | Technology Acceptance Model |

| IS Success Model | Information Systems Success Model |

| UTAUT | Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology |

| TRA | Theory of Reasoned Action |

| TPB | Theory of Planned Behavior |

| PEU | Perceived Ease of Use |

| PU | Perceived Usefulness |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Dependent Variables—AI Implementation Forms—Attitude Components.

Table A1.

Dependent Variables—AI Implementation Forms—Attitude Components.

| Dependent Variable | AI Implementation Form | Attitude Component | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chatbots & VAs | AI-Enabled E-Services | Other Forms | ||

| Intention to Use | [34,36,37,44,47] | Behavioral | ||

| Continuance Intention | [46] | [50] | ||

| Adoption | [35] | |||

| Willingness to Use | [38,45] | |||

| Usage Behavior | [39,54] | [51] | ||

| Engagement | [61] | |||

| Citizen-Initiated Contact | [62] | |||

| Usability | [42] | Cognitive | ||

| Acceptance | [43,48,60] | [53] | ||

| Preferences | [49] | |||

| Perceptions | [52] | |||

| Favorability | [58] | |||

| Experience | [40,59] | Affective | ||

| Satisfaction | [40,41,44,46,54,55,57,63] | [56] | ||

Table A2.

Independent (IV), moderating (MoV), mediating (MeV), and control (CV) variables identified in the reviewed studies.

Table A2.

Independent (IV), moderating (MoV), mediating (MeV), and control (CV) variables identified in the reviewed studies.

| Variable | Definition/Explanation | Study Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prior Experience | IV | Not Defined. | Abbas et al., 2023 [47] |

| MoV | The degree of previous use of technology. | Horvath et al., 2023 [48] | |

| Time Reduction | IV | The difference in the time spent to complete an e-service with and without using the proposed model. | Zabaleta et al., 2019 [35] |

| Autonomy | IV | The number of participants that could complete the e-services autonomously with and without using the proposed model. | Zabaleta et al., 2019 [35] |

| Perceived Ease of Use (PEU) or Effort Expectancy (EE) | IV | Not Defined. | Stamatis et al., 2020 [36] Antoniadis & Tampouris (2021) [37] Patsoulis et al., 2022 [42] Suter et al., 2022 [43] Abbas et al., 2023 [47] Kim et al., 2023 [50] |

| It is easy to use without effort. | Yang & Wang, 2023 [53] | ||

| The level of ease associated with the use of a system. | Abed, 2024 [54] | ||

| Perceived Usefulness (PU) or Performance Expectancy (PE) | IV | Not Defined. | Stamatis et al., 2020 [36] Antoniadis & Tampouris (2021) [37] Alhalabi et al., 2022 [41] Patsoulis et al., 2022 [42] Suter et al., 2022 [43] Willems et al., 2022 [45] Abbas et al., 2023 [47] Kim et al., 2023 [50] Moreira & Naranjo-Zolotov, 2024 [60] |

| The degree to which an individual believes that using the system will help him or her to attain gains in job performance. | Abed, 2024 [54] | ||

| Cognitive Communication | IV | Cognitive based virtual agents’ interaction between government and citizens for e-gov services. | Chohan et al., 2021 [39] |

| Trust | IV | Not Defined. | Chohan et al., 2021 [39] Abbas et al., 2023 [47] |

| IV MoV | Trust in chatbots. | El Gharbaoui, El Boukhari, et al., 2024 [55] | |

| Trust in recommender systems. | El Gharbaoui, El Boukhari, et al., 2024 [56] | ||

| Perceived Risk | IV | The subjective belief that there is a probability of suffering a loss in pursuit of a desired outcome [51]. | Chohan et al., 2021 [39] Pribadi et al., 2023 [51] |

| Public perception of possible adverse consequences for themselves. | Yang & Wang, 2023 [53] | ||

| Personalization | IV | The provision of personally relevant products and services according to the user’s unique characteristics and demands. | Zhu et al., 2021 [40] Zhu et al., 2022 [46] |

| Voice Interaction | IV | A function allows robots to make human-like communication with users. | Zhu et al., 2021 [40] Zhu et al., 2022 [46] |

| Enjoyment | IV | The extent to which using an IS product or service is perceived as enjoyable, fun, and pleasurable. | Zhu et al., 2021 [40] Zhu et al., 2022 [46] |

| Learning | IV | A means of satisfying users’ desire to acquire new knowledge. | Zhu et al., 2021 [40] Zhu et al., 2022 [46] |

| Condition | IV | The perceived utility received from using chatbots to meet the mental health demands of the current condition a person faces. | Zhu et al., 2021 [40] Zhu et al., 2022 [46] |

| Information Quality | IV | The extent of how accurate, relevant, precise and complete the information provided by the IS is and how it fits users’ needs [44]. | Alhalabi et al., 2022 [41] Tisland et al., 2022 [44] |

| Usage Characteristics | IV | Not Defined. | Alhalabi et al., 2022 [41] |

| Perceived Satisfaction | IV | Not Defined. | Alhalabi et al., 2022 [41] |

| Importance | IV | Not Defined. | Alhalabi et al., 2022 [41] |

| Acceptance of Automation | IV | Not Defined. | Alhalabi et al., 2022 [41] |

| Socio-Demographic Factors | IV | Age. | Suter et al., 2022 [43] Srikanth & Dwarakesh, 2023 [52] Pislaru et al., 2024 [61] |

| CV | Kim et al., 2023 [50] | ||

| IV | Gender. | Suter et al., 2022 [43] Srikanth & Dwarakesh, 2023 [52] | |

| CV | Kim et al., 2023 [50] | ||

| IV | Education. | Suter et al., 2022 [43] Pislaru et al., 2024 [61] | |

| IV | Monthly income. | Suter et al., 2022 [43] Pislaru et al., 2024 [61] | |

| IV | Residence (rural or urban). | Suter et al., 2022 [43] Pislaru et al., 2024 [61] | |

| IV | Employment Status. | Pislaru et al., 2024 [61] | |

| Political Support | IV | An attitude by which individuals situate themselves, either favorably or unfavorably, vis-á-vis the political community, the political regime, and the political authorities. | Suter et al., 2022 [43] |

| Trust in Technology | IV | The belief that a technology has the attributes necessary to perform as expected. | Suter et al., 2022 [43] |

| A person’s belief that the operation of a technology can be trusted to obtain online information. | Pribadi et al., 2023 [51] | ||

| Not Defined. | Yang & Wang, 2023 [53] | ||

| System Quality | IV | The extent of how consistent, easy to use and responsive an IS is, and to what degree it fits the users’ needs. | Tisland et al., 2022 [44] |

| Service Quality | IV | The extent of the reliability, responsiveness, assurance and empathy of an IS. | Tisland et al., 2022 [44] |

| Services that provide up-to-date, accurate, and well-structured information. | Kim et al., 2023 [50] | ||

| Human Empowerment | IV | A personally meaningful increase in power that a person obtains through his or her own efforts. | Tisland et al., 2022 [44] |

| Trusting Beliefs | IV | The confident truster perception that the trustee has attributes that are beneficial to the truster. | Tisland et al., 2022 [44] |

| Competence of User | CV | An individual’s belief in his or her capability to use the system in tasks with relevant knowledge, skills and confidence. | Tisland et al., 2022 [44] |

| Impact of System Usage | CV | The degree to which an individual can influence task outcomes based on the use of the system. | Tisland et al., 2022 [44] |

| Meaning of System Usage | CV | The importance an individual attaches to system usage in relation to his or her own ideals or standards. | Tisland et al., 2022 [44] |

| Self- Determination | CV | An individual’s sense of having choices (i.e., authority to make his or her own decisions) about system usage. | Tisland et al., 2022 [44] |

| Data Privacy | IV MoV | Individuals’ control over the release of personal information including its collection, use, access, and correction of errors [45]. | Willems et al., 2022 [45] |

| Personal Information | IV MoV | The amount of personal information a user is required to share. | Willems et al., 2022 [45] |

| Anthropomorphic Design | IV MoV | Human likeness design. | Willems et al., 2022 [45] |

| Hedonic Motivation | IV | Users’ perceptions of the engagement and experiential aspects of technology. | Abbas et al., 2023 [47] |

| Habit | IV | Not Defined. | Abbas et al., 2023 [47] |

| Social Influence | IV | Users’ perceptions of attitudes and priorities of significant others. | Abbas et al., 2023 [47] |

| The extent to which an individual feels that significant others think he or she should use the new system. | Abed, 2024 [54] | ||

| Not Defined. | Moreira & Naranjo-Zolotov, 2024 [60] | ||

| Facilitating Conditions | IV | Technology availability or needed infrastructure to benefit from the technology. | Abbas et al., 2023 [47] |

| The extent to which a person believes that an organizational and technical infrastructure exists to support the use of the system. | Abed, 2024 [54] | ||

| Human Involvement | IV | The degree of human involvement in the process of decision making in public services. | Horvath et al., 2023 [48] |

| AI Literacy | MoV | A user’s ability of recognizing instances of AI and distinguishing between technological artefacts that use and do not use AI. | Horvath et al., 2023 [48] |

| Proactivity | IV | The capability of a chatbot to autonomously act on behalf of users. | Ju et al., 2023 [49] |

| The capability of a chatbot to provide additional, useful information to keep the conversation alive. | Li & Wang, 2024 [59] | ||

| Conscientiousness | IV | The capacity of a chatbot to demonstrate attentiveness to the conversation at hand. | Ju et al., 2023 [49] |

| The capability of a chatbot to exhibit focused engagement in the ongoing conversation. | Li & Wang, 2024 [59] | ||

| Communicability | IV | The capacity of a chatbot to convey its underlying features and interactive principles to users. | Ju et al., 2023 [49] |

| Emotional Intelligence | IV | The capability of a chatbot to appraise and express feelings, regulate effective reactions, and harness emotions to solve problems. | Ju et al., 2023 [49] |

| Identity Consistency | IV | The capability of a chatbot to present itself as a particular social actor. | Ju et al., 2023 [49] |