Abstract

Online commerce has been growing rapidly in an increasingly digital world, and gamification, the practice of designing games in a context outside the industry itself, can be an effective strategy to stimulate consumer engagement and conversion rate. This paper describes the design process involved in introducing gamification into an online shop that is supported by two game servers of the same kind, namely one in the United States of America (US) and another in Portugal (PT). Through the various phases of the design thinking process, a gamified system was implemented to meet the needs of various types of users frequently found in the shops. The gamification elements used were intended to increase user engagement with the shops so that they would become more aware of existing products and the introduction of new products, promoting purchase through intangible challenges and rewards. The impacts on server revenues and user satisfaction (N = 138) were evaluated one month after introducing the gamification techniques. The results show that gamification has a positive effect on users, with a significant increase in consumer interaction in both shops. However, from a business point of view, the results show only an increase in revenue for the US shop, while the Portuguese shop shows no significant differences compared to previous months. Of the two user groups analyzed, only those who frequent the US shop show receptivity toward intangible rewards, with tangible rewards (discounts) being a greater motivating factor for both groups.

1. Introduction

Online commerce has been growing rapidly in an increasingly digital world, with the total share of online sales reaching 18% in 2020 compared to 7.4% in 2015 [1]. This growth results both from the adoption of online commerce by large, medium, and small businesses, and from the impact of COVID-19, which encouraged the use of alternative means of consumption, with the practice having continued even after the resumption of traditional commerce [2]. Thus, the ease of access to various online stores and greater consumer demand have generated the need for companies to stand out, seeking to turn the use of their online stores into a memorable experience to gain trust and loyalty from consumers [3].

Gamification describes the adoption of mechanics and design methods that make games appealing, immersive, and interactive outside of the gaming industry [4,5]. Online commerce is an example where these aspects can be applied to attract the public and stimulate consumption, allowing a better shopping experience and consequently increasing a company’s profits. On the other hand, diligent consumers also benefit from the possibility of extra rewards. Gamification can, thus, be an effective strategy to motivate consumers and promote their involvement, thus increasing the conversion rate and boosting consumer confidence in the company.

Grand Theft Auto V (GTA V) is a game first released in 2013, distributed, published, and developed by Take-Two Interactive and its subsidiaries, Rockstar Games and Rockstar North. An open-source modification of GTA V called FiveM [6] was made available in 2015 by the group Citizenfx (Cfx.re) [7]. This modification provides the possibility for players to create their own modified servers, that is, through script development, create experiences and possibilities not integral to the original game. For players who play on these modified servers, this has no associated costs; however, there are development and maintenance costs of the machine the server is hosted on that must be considered. Therefore, there is the possibility for players who wish to do so to contribute monetarily to these costs by making donations and buying products for use on the server itself. These products vary, ranging from faster server entry if the server is at full capacity to access to custom clothing and cars, which allows a player to customize his/her character and stand out from other players. These transactions are handled by Tebex [8], a company founded in 2012 in the United Kingdom (UK), which provides a monetization platform for modified servers of various games. On this platform, it is possible to create an online store that displays products and process payment for them. Therefore, the research questions of this study are the following:

- How effective is online store gamification for a game server business?

- How do users in different countries react to gamification of an online store?

This paper describes the design thinking approach taken to introduce gamification elements in the online stores of two FiveM game servers, one based in the United States of America (US) and the other in Portugal (PT).

2. Literature Review

Recent years have seen an evolution in the use of technology, and technology is now increasingly used to encourage and support a variety of actions considered beneficial on both a personal and social level [8]. Gamification has been the technological development that has gained the most attention in both academic and business fields [9,10]. Some researchers describe it as the fusion between utilitarian systems and hedonic systems [11,12]. Others define it as the idea of using electronic game design elements in non-game contexts to increase user motivation, interactivity, and retention in a given service [9]. This concept was first mentioned in 1998 under the term captology (the study of computers as persuasive technologies) by Fogg [13]. This author defined a persuasive technology as that which is used with the intention of affecting the attitudes or behaviors of those who use it. The growing relevance of this topic has led to more and more articles being published on the effects of the use of such technologies on gratification and their effects on consumers in various sectors (online commerce, education, health, data collection, and internal organizational systems [8]).

The use of gamification implies the presence of game elements, namely points, leaderboards, challenges, badges, levels, and rewards, among others, as listed in Table 1. These representations are intended to provide users with a sense of progression and short-term rewards, thereby keeping them engaged in the system [8,14].

Table 1.

Game element terminology (Adapted from [15]).

Each element has been studied individually to see how it affects users. Badges have been the subject of further research, with advantages associated with the use of these strategies, such as better academic results (education), friendly competition and comparisons (social networking), as well as increased interactivity of users (online commerce) [16]. On the other hand, the use of ranking tables presents a competitive component with the possibility of causing negative effects on certain users who are not competitive by nature, such as lack of interest and motivation [17]. To minimize these effects, guidelines have been developed for better design of rating tables when applied to gamification [18,19].

What began as a simple adaptation of elements that make games appealing outside of the game industry itself has now evolved into a broad area of investigation of the concepts themselves. However, some elements can have both positive and negative effects on different levels, depending on the user who is interacting with the system. This phenomenon was studied by Hamari et al. [8], who mention that the experiences created by gamified services are dependent on the system being gamified and users, namely their motivations, behaviors, and preferences. To establish a connection between the various elements previously mentioned and different types of users, several models for categorizing users have been defined. These models help the system being gamified achieve the best result by involving the largest number of users.

To understand how various types of users interact with gamified systems, models have been used and adapted based on player profiles that are built to categorize users by grouping them based on common motivations. In 1996, Bartle [20] identified four types of players (see Table 2) interacting with MUDs (multi-user dungeons) and role-playing games (RPGs), and their motivations. This model has been widely studied and used as a basis for developing user-focused gamified systems [21,22,23,24].

Table 2.

The four types of players defined by Bartle and their description (adapted from [20]).

Based on this model, a questionnaire was developed that aims to categorize players, and despite the limitations of the model itself, it has been used as a reference for creating gamified games and systems [25,26,27]. Although this model is popular in the gamification field, Bartle [28] mentions that when you really understand what is important for the gamification design you are developing, more appropriate models can be inferred.

Developed and presented by Andrzej Marczewski in 2015 [29], this work describes six user types that are created specifically to assist in the creation of gamified systems (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Hexad player typology (adapted from [29]).

To understand how the player types in the aforementioned model interact with the different gamification elements that exist, Tondello et al. [30] conducted a questionnaire to find out which gamification elements are preferred by each player type. The results of this questionnaire are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Gamification elements suggested by Tondello et al. for the player types in the Hexad model based on survey results (adapted from [29,30]).

Through this questionnaire and the results obtained, the effectiveness of the Hexad model in helping to create personalized gamified systems has been empirically validated by Tondello et al. [30,31]. Both Bartle’s and Marczewski’s models, which categorize various player types, are in line with what Yu-kai Chou describes on this topic [32]. According to this author, gamification is not just the introduction of PBL’s (points, badges, and leaderboards) in a boring activity. A good gamification implementation not only considers the types of users in question but also answers the questions, “What are my goals for this experience?” and “How do I want the user to feel?”.

To assist in finding answers to these questions, Yu-kai Chou developed the Octalysis Framework which assumes that all player behaviors have at least one of eight main motivations: epic meaning, accomplishment, empowerment, ownership, social influence, scarcity, unpredictability, and avoidance [33]. The last three motivations tap into the human nature of loss aversion; typically, if there is no action on the part of a consumer, the consumer will lose something with intrinsic value. As an evolutionary trait, humans have a predisposition toward fear of loss and fear losing over winning. Point-based reward systems are a common gamification tactic. Not only do these elements provide intrinsic value to users for making a purchase, but they also often incorporate some sense of losing points in each period. These points have no monetary value, but their intrinsic value makes consumers feel a sense of loss if they are not fully redeemed. This can be a motivation to encourage customers to make purchases soon.

According to the E-commerce report 2021 [34], COVID-19 has boosted the growth and, therefore, the profit of online commerce by 19% in 2020 and 22% in 2021 to a total of 28% and 34%, respectively. In the United States, online commerce accounted for 14% of all sales in 2020 and is estimated to grow to 22% by 2025 [35]. In Portugal, during 2020, online commerce accounted for 20% of all sales, [36] with many purchases made from foreign companies, such as El Corte Ingles, Zara and Amazon [37]. In [38], it is possible to verify that the percentage of e-shoppers has growth from 51% in 2019 to 67% in 2022, which may be a result of the change of habits due to COVID-19. Sheetal et al. stated that due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the volume of e-commerce transactions increased, and gamification as an engagement model provided a better retail experience and enhanced the whole e-commerce experience [39]. Additionally, Fedirko et al. found that only 5% of the respondents of their study stated that they suffered a decline in online revenue after global lockdown, while 32% experienced a raise of 50–100% [40]. This might indicate that the pandemic positively influenced the habits of consumers and the attitudes of companies.

Online shopping has numerous advantages for customers, allowing them to save time and money compared to the traditional experience obtained in a physical store. However, because there are low barriers to entry in this space, competition is incredibly high for the limited attention span of consumers. As a result, promoting customer loyalty and engagement is much more valuable in this context.

With the previously mentioned growth in the number of online purchases, users are looking to save time and money in one way, as well as to gain convenience and comfort. On the other hand, online stores are increasingly looking for unique ways to retain customers and build trust in their brand. Gamification is, therefore, an effective strategy for achieving the goals of attracting consumers, boosting brand trust, and increasing profits. Gamification has been found by several studies to have a positive effect on user engagement and enjoyment, which leads to product loyalty [41].

Regarding what the literature reports about the effectiveness of gamification, researchers agree that gamification tactics work. Gamification strongly influences motivation in returning customers to websites [12] through positive reinforcement of customer engagement with rewards. This positive reinforcement can help create and maintain loyalty among consumers as they feel trust in the online store they have visited.

According to Behl et al. [12], what started as simple spin the wheel contests, where users can receive discounts, has evolved into awarding points, badges, and promotions for frequent purchases and visits. These strategies inspire temptation in users to spend more time in the store, making them more aware of new products and promotions. The analysis by Karac and Stabauer [42] identifies some online businesses that are applying the elements of gamification and relate their success to the motivations defined in the Octalysis Framework (see Table 5 and Table 6).

Table 5.

Companies and applied gamification elements.

Table 6.

Motivations used by each company.

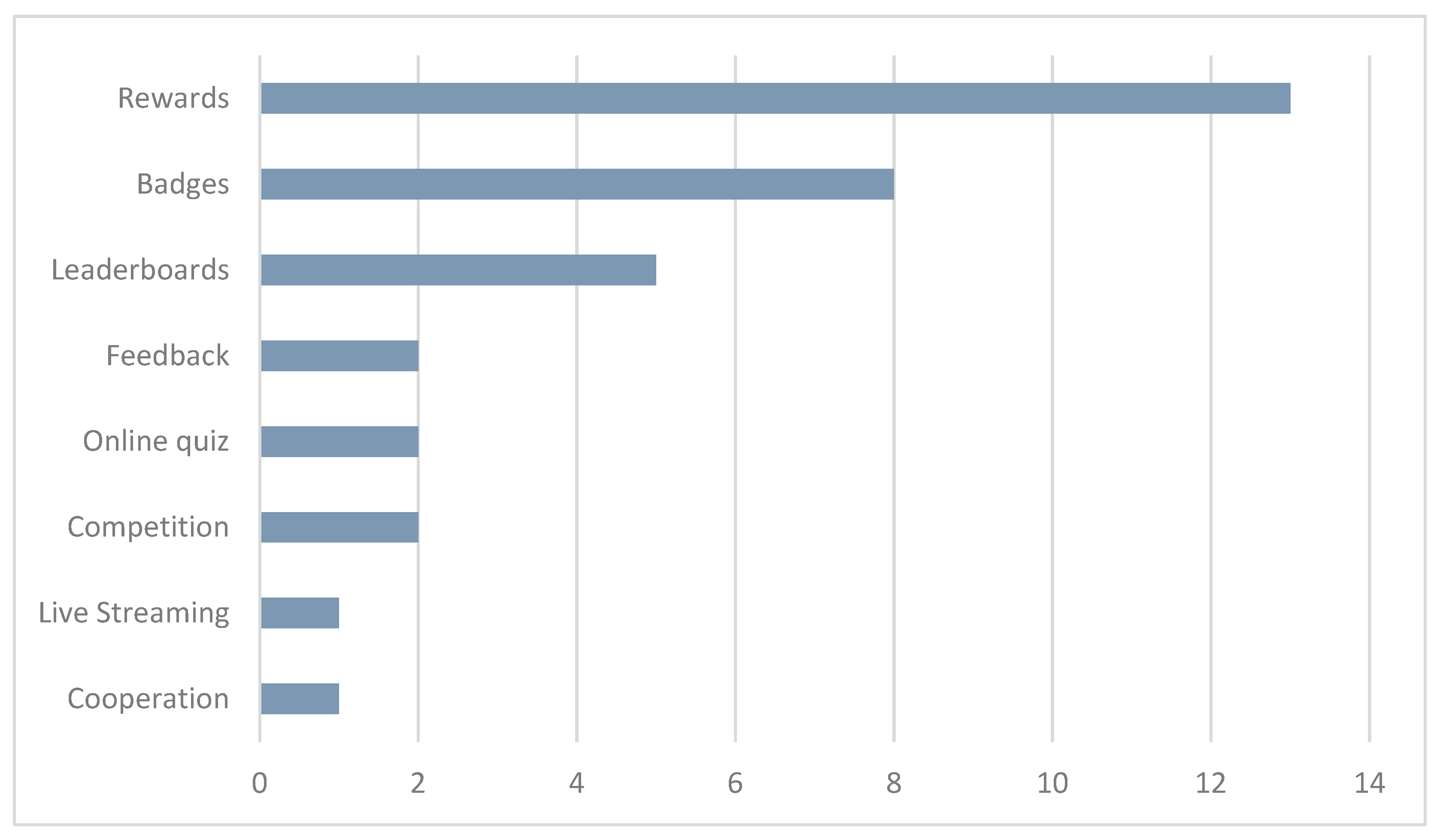

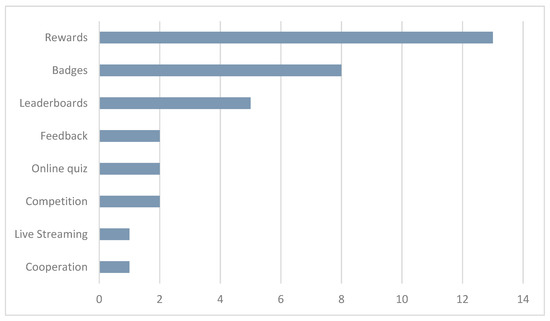

In a study by Azmi et al. [41], 17 papers on gamification in e-commerce were analyzed. The most applied strategies were rewards, badges, and leaderboards (Figure 1). All the papers showed positive effects, except for a study conducted by Kim et al. [43], who indicated that gamification can be counterproductive if its use is forced on users rather than being optional.

Figure 1.

Most used gamification elements in the works analyzed by Azmi et al. (adapted from [5]).

The goal of gamification is to affect human behaviors [44], and, thus, iterations must be designed with users and context in mind.

With these findings in mind, this research aimed to identify if the usage of gamification in an online game server in two different geographical locations—Portugal and United States—showed the identified benefits in previous research works and if the two different communities of gamers presented a different profile toward gamification, which led to different results in terms of sales.

3. Research Design

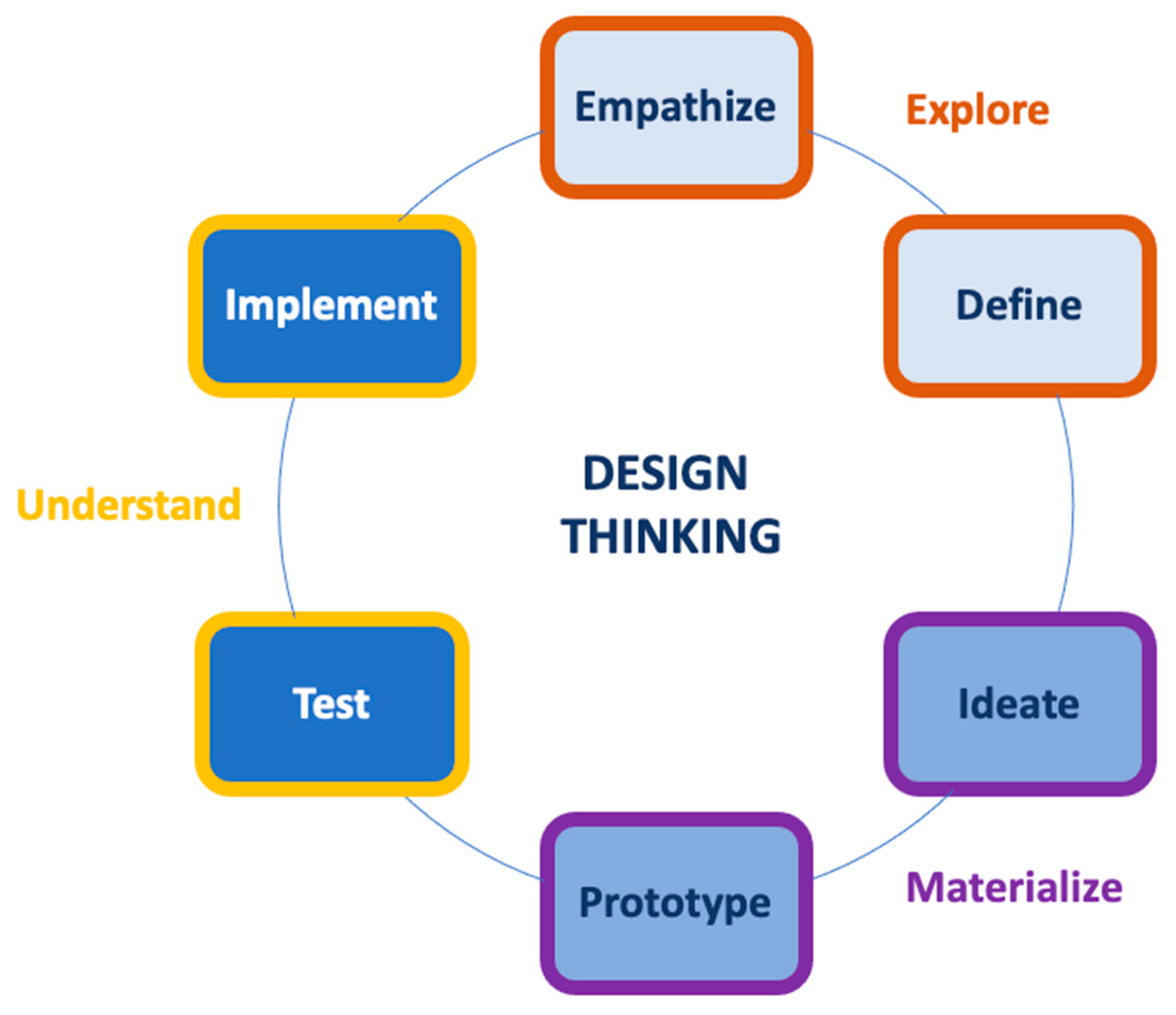

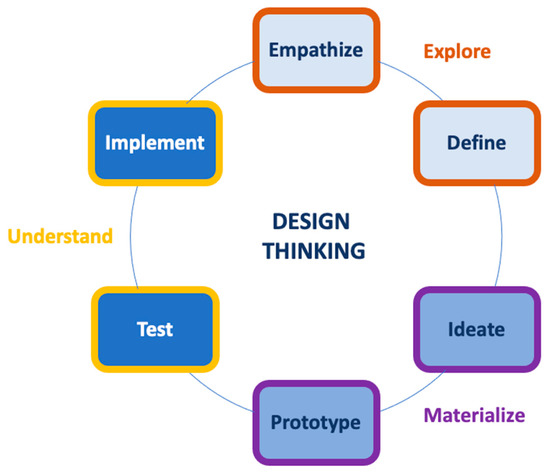

This project followed a design thinking approach [45]. It is composed of six phases: Empathize, Define, Ideate, Prototype, Test and Implement (see Figure 2). In the following subsections, the application of the design thinking methodology of this research is presented.

Figure 2.

Design thinking approach.

3.1. Empathize

To better understand the server’s users, their online shopping habits, and what motivates them to play, the following research plan was developed. The server was created in the summer of 2021, a decision based on a market opportunity and uninfluenced by the COVID-19 pandemic. After being live for one year, the next step was to investigate whether gamification would stimulate sales revenue. A user research survey was conducted during the Empathize phase to gather online shopping habits and what motivates users to play the game. First, a quantitative survey was available for users to answer between 10 May and 10 June 2022 through google forms (see Table 7). Secondly, a qualitative one-on-one interview was conducted with three users that provided a way to be contacted. The data collection included 36 answers from the American server and 46 from the Portuguese server.

Table 7.

Online survey results (percentages of out-of-scope responses have been discarded).

The data relating to the first question, “How often do you shop online?”, reveal a substantial difference in the frequency with which US server users shop online. From this sample, 17% indicated that they shop every day, 39% indicated once a week, 25% indicated once a month, and 14% indicated once every three months. When compared to the results from the PT server, there are lower percentages of 2%, 12%, 33%, and 41%, respectively.

For the second and third questions, “Have you ever shopped at a gamified online shop that applies the concepts described above?” and “Did you feel that these concepts had an impact on your purchasing decision?”, on both servers, more than half of the users stated that they had already shopped at a gamified shop, and 80% said that their purchasing decision was affected by gamification. Of the concepts most used in gamification, on both servers, there was a greater preference for rewards and discounts, which, in an online commerce context, is very directly related to saving money. The users on the US server also showed a high level of interest in the concepts of levels and progression, while no significant differences were found among the various concepts for the users on the PT server.

With regard to whether gamification benefits or harms consumers, the options with the most answers were “Neither harms nor benefits” and “Very beneficial”. When asked to justify their answer, the users who chose the first option mentioned their indifference toward the gamification concept since what motivated them to go to the shop was the search for a specific product, regardless of the shop’s suggestions. On the other hand, the users who identified gamification as beneficial mentioned the following advantages:

- The possibility of obtaining products at a cheaper price than the original.

- Rewarding actions, such as rating and writing an opinion about a product purchased, helps future consumers in their choice and promotes interaction.

- Points and badges that increase users’ level not only give the satisfying feeling of progression, but they also increase retention by giving users a goal to achieve, thereby keeping them coming back.

Among some users, concern was registered that implementing gamification in an environment involving money might lead some consumers to spend more than they need or even have. Shopping is a behavior that, for some people, can be too stimulating to the point of creating real structural brain changes and addictive behavior. The stimulation can become too much when the importance of buying a product and/or the buying process is exaggerated [46]. Gamification in the context of online commerce is often presented as offering a unique and memorable experience to consumers to stimulate their curiosity, increase their interaction with the shop, and promote their return. It is, therefore, possible that gamification may trigger harmful behavior in certain users, and this should be a concern when designing gamification, with the possibility of limiting the act of purchasing for these types of users.

Regarding how gamification affects a company, most users identified it as “Beneficial” since the rewards offered encourage more online shopping and stimulate consumption, which in turn leads to an increase in the company’s profits.

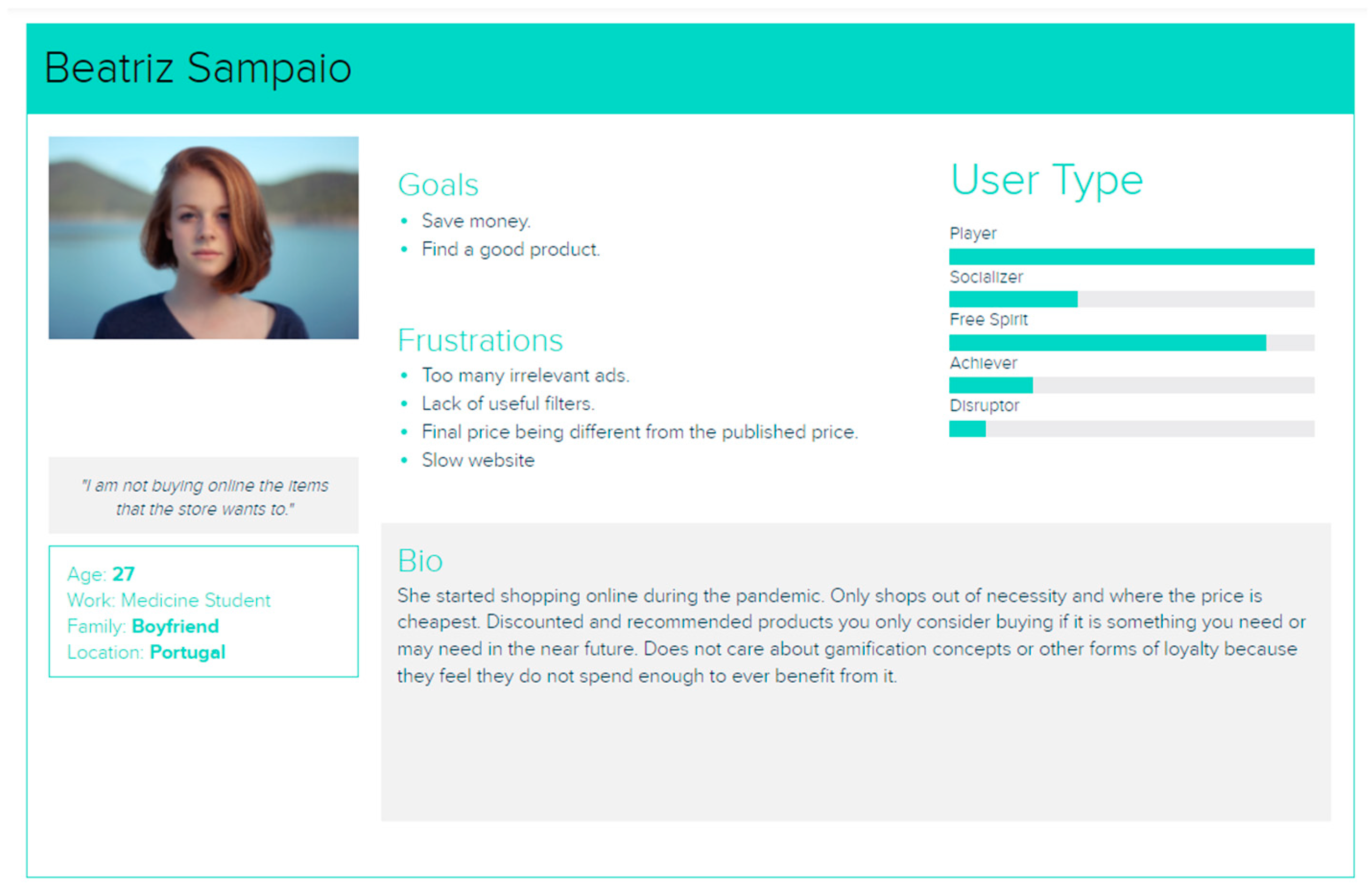

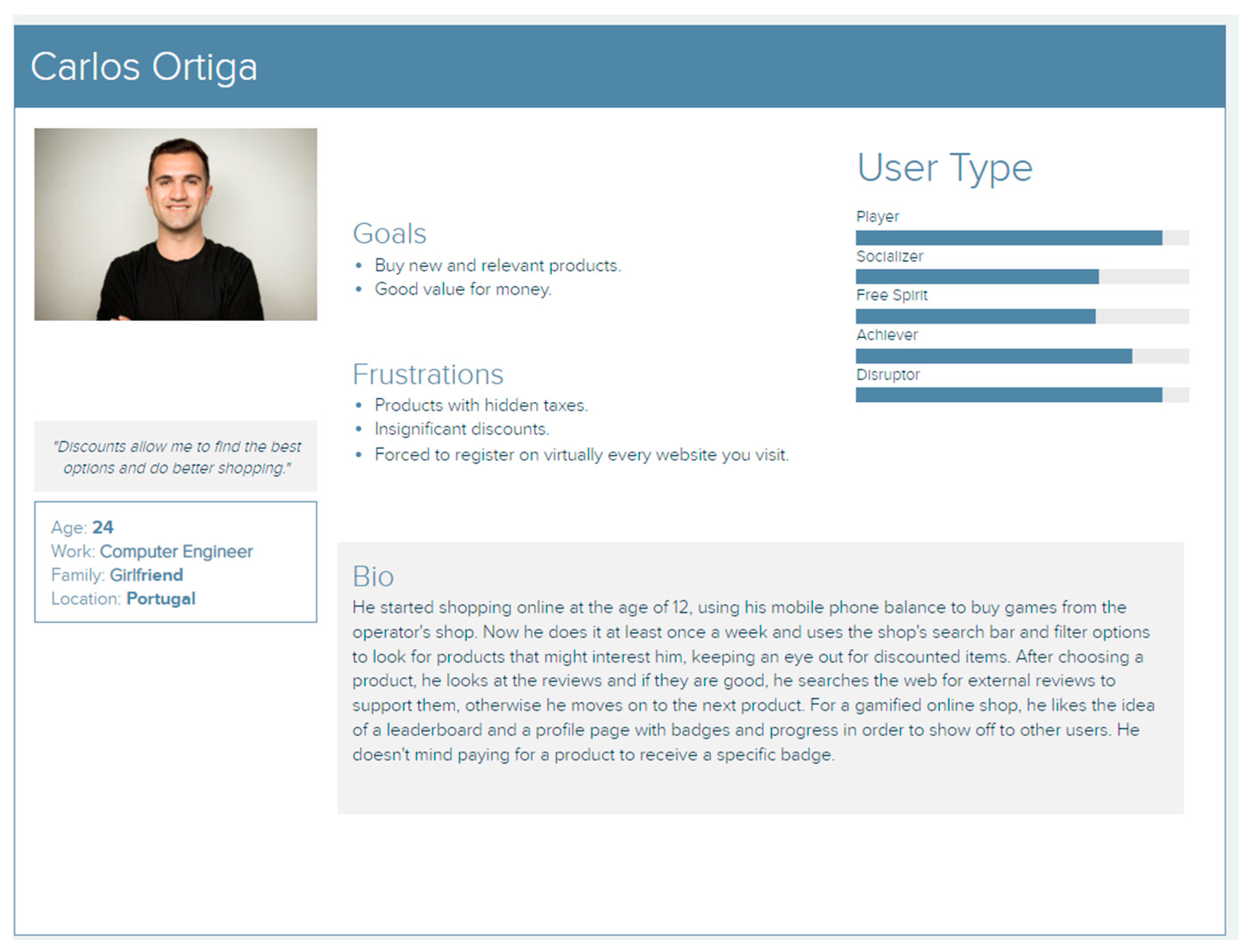

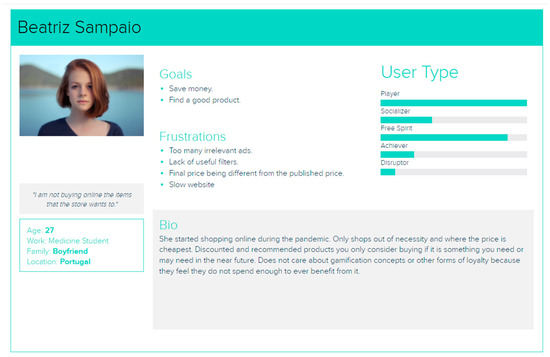

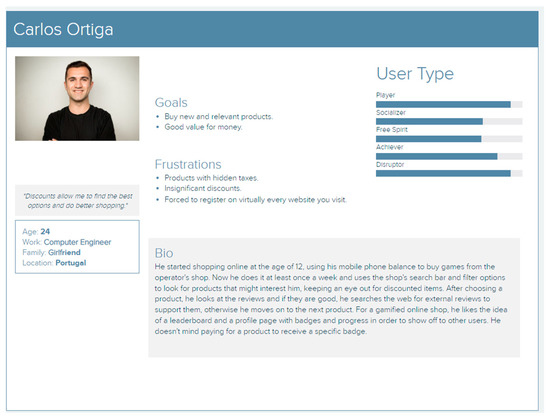

3.2. Define

The launch of new products in the game platform is not executed in a strategic way, and users only go to the shop when they want to buy a specific product. Thus, the application of a new methodology was adopted to increase confidence in product quality and encourage regular user returns. Based on the questionnaire and interviews conducted, two personas were developed, grouping the similar characteristics of various users. They are fictitious personas that represent users who interact with the shop. Of the two personas, one—Beatriz Sampaio—differs very visibly from the other for not showing any interest in gamification concepts or in the possibility of discounts (see Figure 3). For this persona, any online purchase is only an immediate need, and she assumes that she does not spend enough money to ever take advantage of it. The other—Carlos Ortiga—has a habit of shopping online and feels motivated by gamification (see Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Persona “Beatriz Sampaio” (Photo by Christopher Campbell obtained from https://unsplash.com/ (accessed on 27 February 2023)).

Figure 4.

Persona “Carlos Ortiga” (Photo by Mostafa Kord Zangeneh obtained from https://unsplash.com/ (accessed on 27 February 2023)).

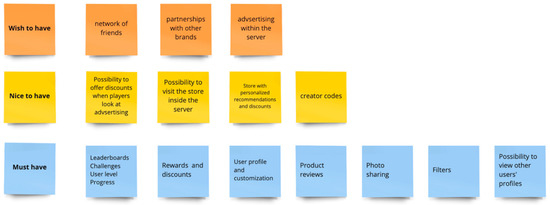

3.3. Ideate

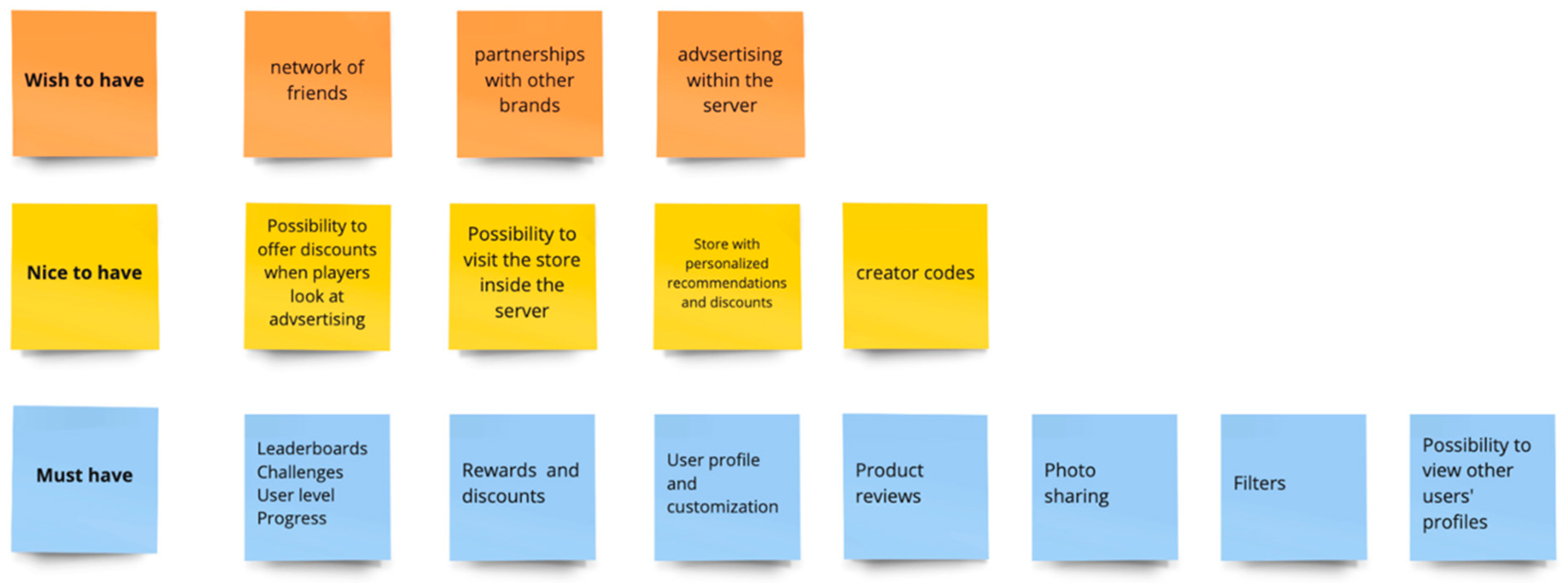

After defining the personas, a brainstorming (see Figure 5) was carried out to explore ideas and key concepts for the functionalities that the new gamified store would need to have to attract each type of consumer. Thus, to complete the implementation of gamification in the store, the following functionalities are needed: leaderboards, challenges, user level, badges, and user profile with personalization.

Figure 5.

Results of brainstorming session.

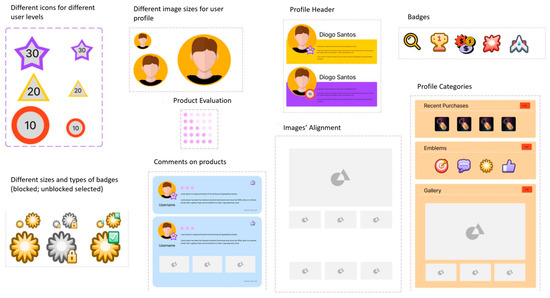

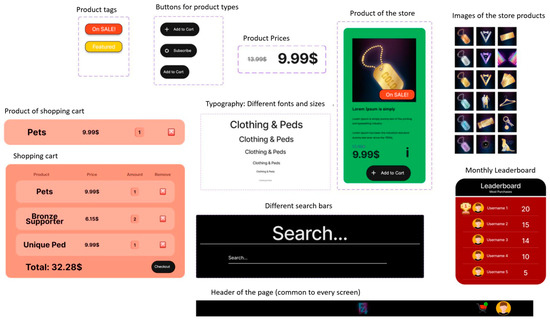

3.4. Prototype

In the Prototype phase, the prototype was developed in the application Figma [47]. Since we implemented gamification concepts in an already established online store, aspects such as the flow between the various pages, structure, and core palette were kept relatively similar to the existing one.

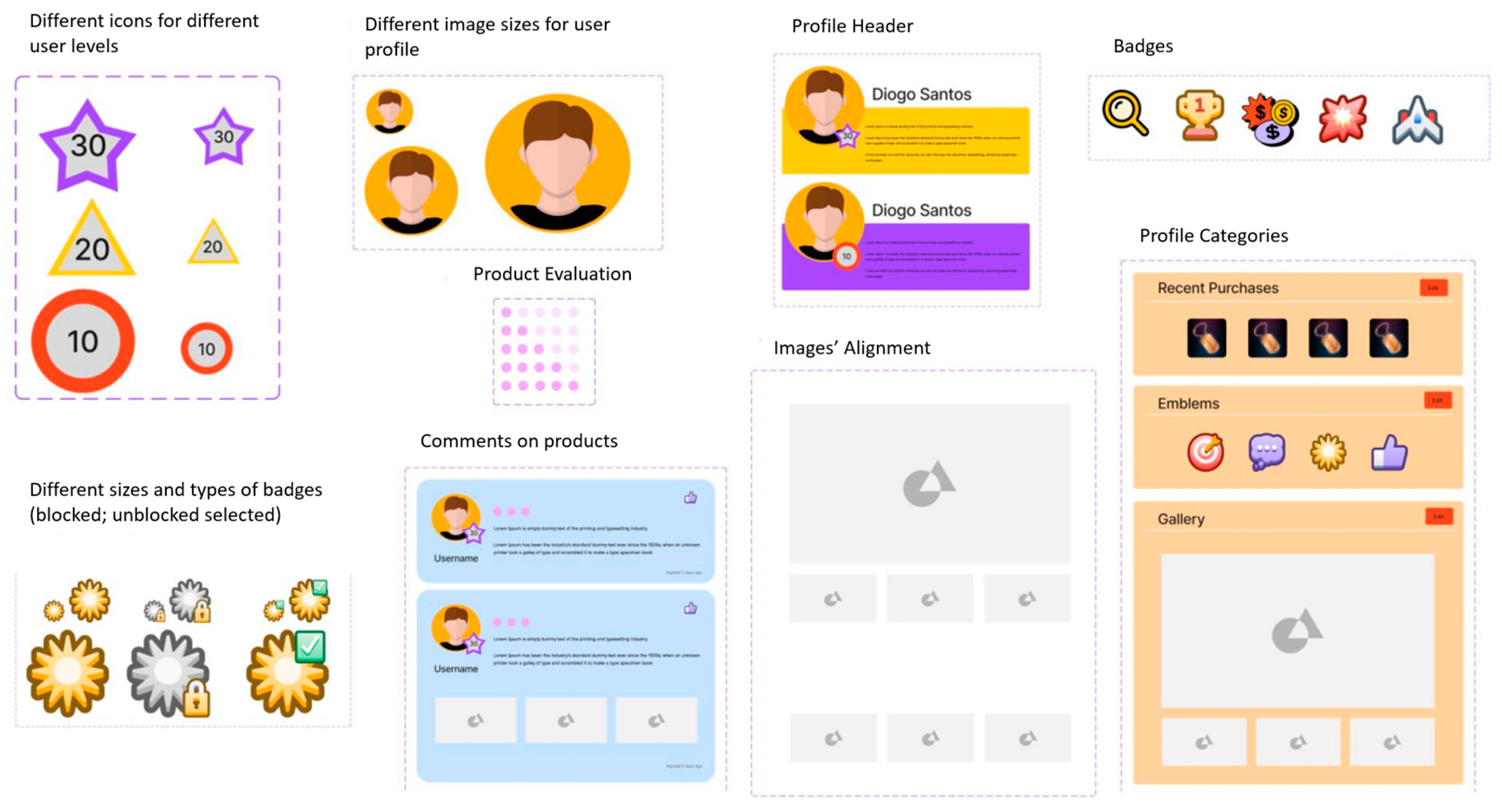

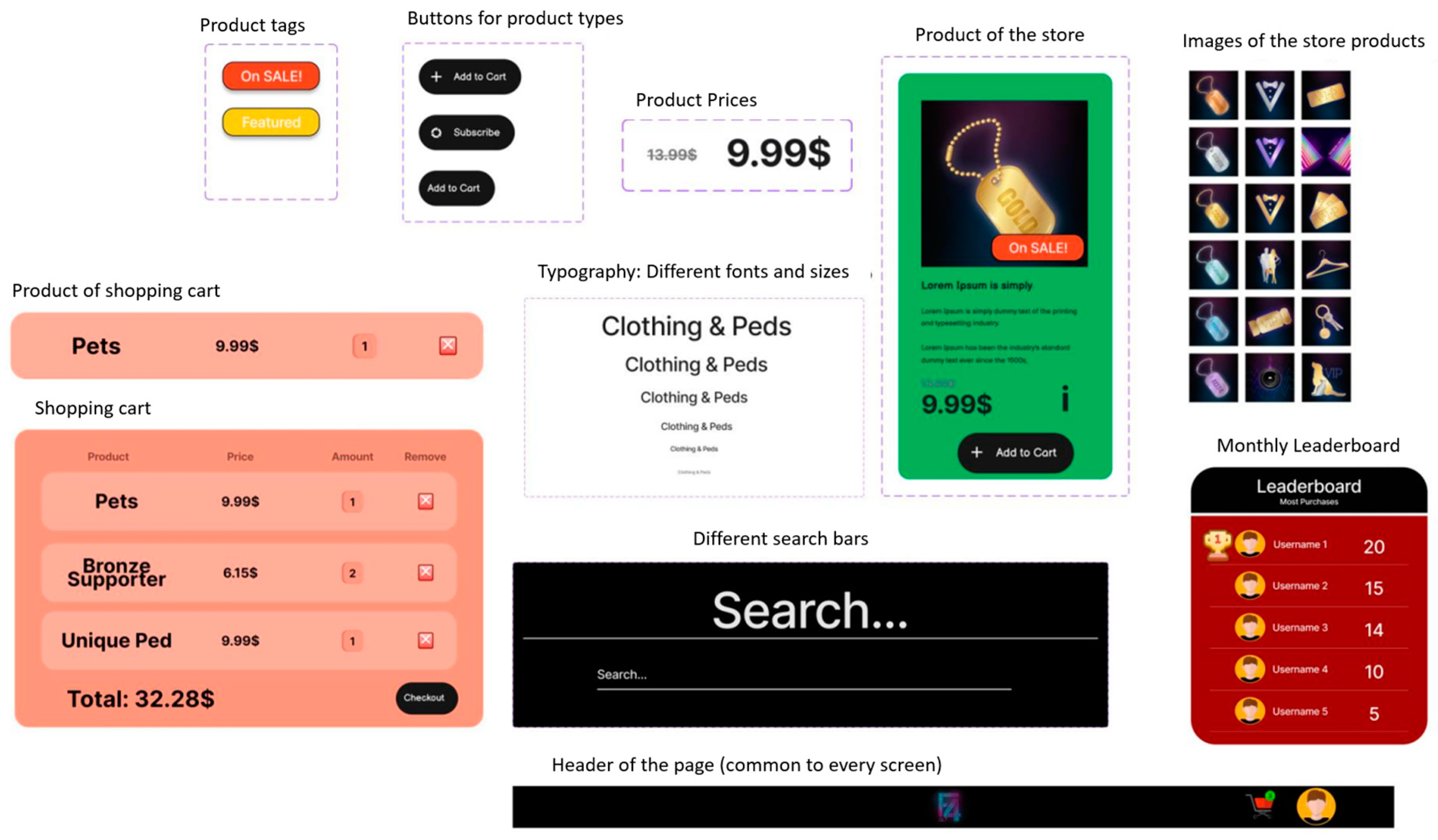

Simple components, such as user profile image, different text sizes, and various user levels and badges, were used to build more complex elements, such as a leaderboard, product ratings, and user profile page, among others. Changes to these simple components are reflected in all the complex components they are part of, maintaining their consistency throughout development. These components are illustrated in Figure 6 and Figure 7 with a brief description and a reference to the components by which they are composed of.

Figure 6.

Prototype components (part 1).

Figure 7.

Prototype Components (part 2).

To build a leaderboard, we considered the suggestions by Kim [19]. The way positions are calculated should convey a sense of impartiality. To agree with this point, the price of each purchase is not considered, but rather the number of purchases made by each user. Challenges are an integral part of the new system since they are intended to keep users entertained. The rewards obtained, in the form of badges, will be used to customize users’ profiles. The development of challenges, both from a visual and design perspective, was based on a proposed framework by Hamari and Eranti [48]. According to the authors [48], challenges are composed of three layers: Identifier, Completion Verification, and Reward. Thus, the following six distinct types of challenges were created:

- Navigation to certain pages in the store.

- Evaluation of purchased products.

- Uploading photos to a store.

- Buying certain products.

- Achieving certain user levels.

- Logging in to the store daily.

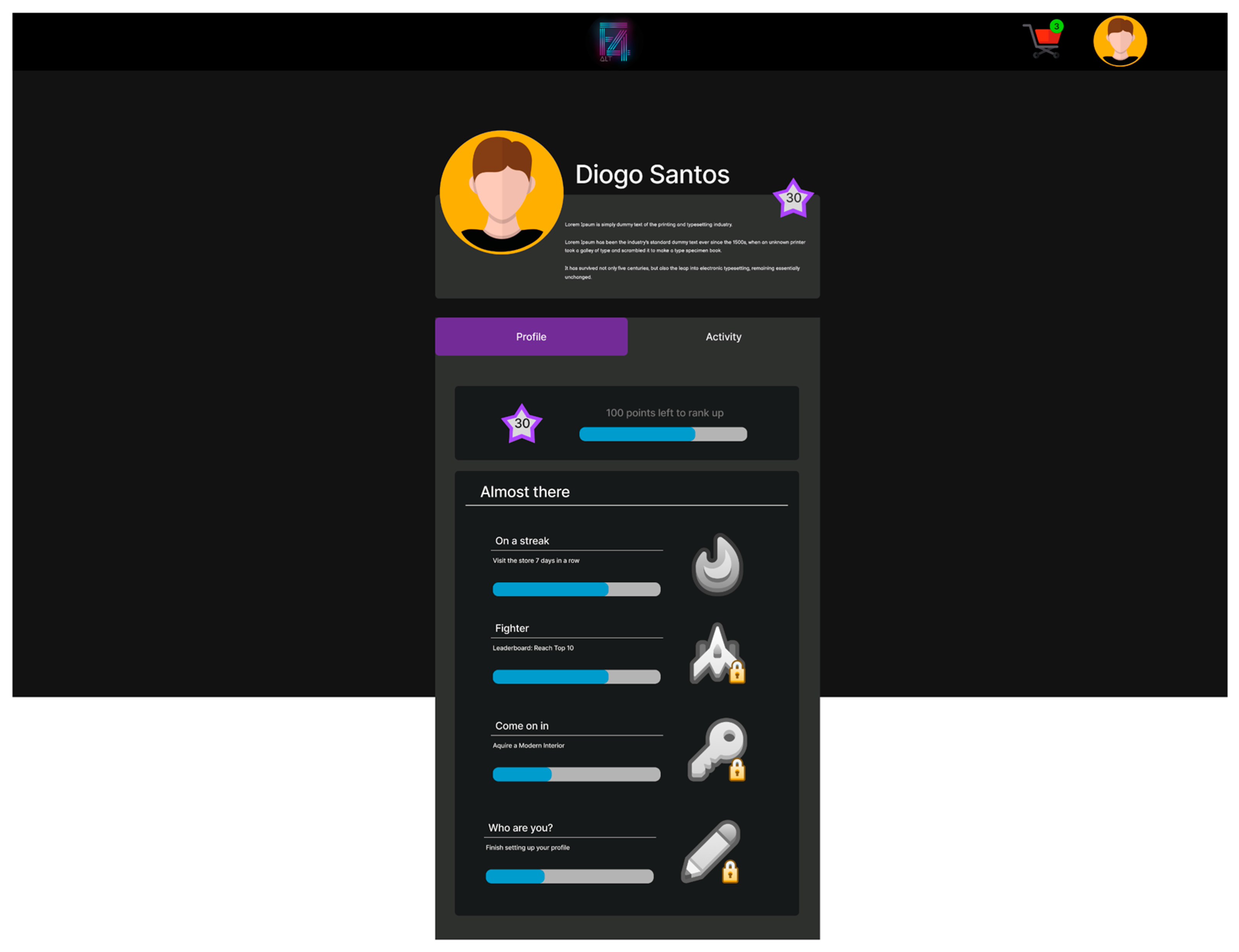

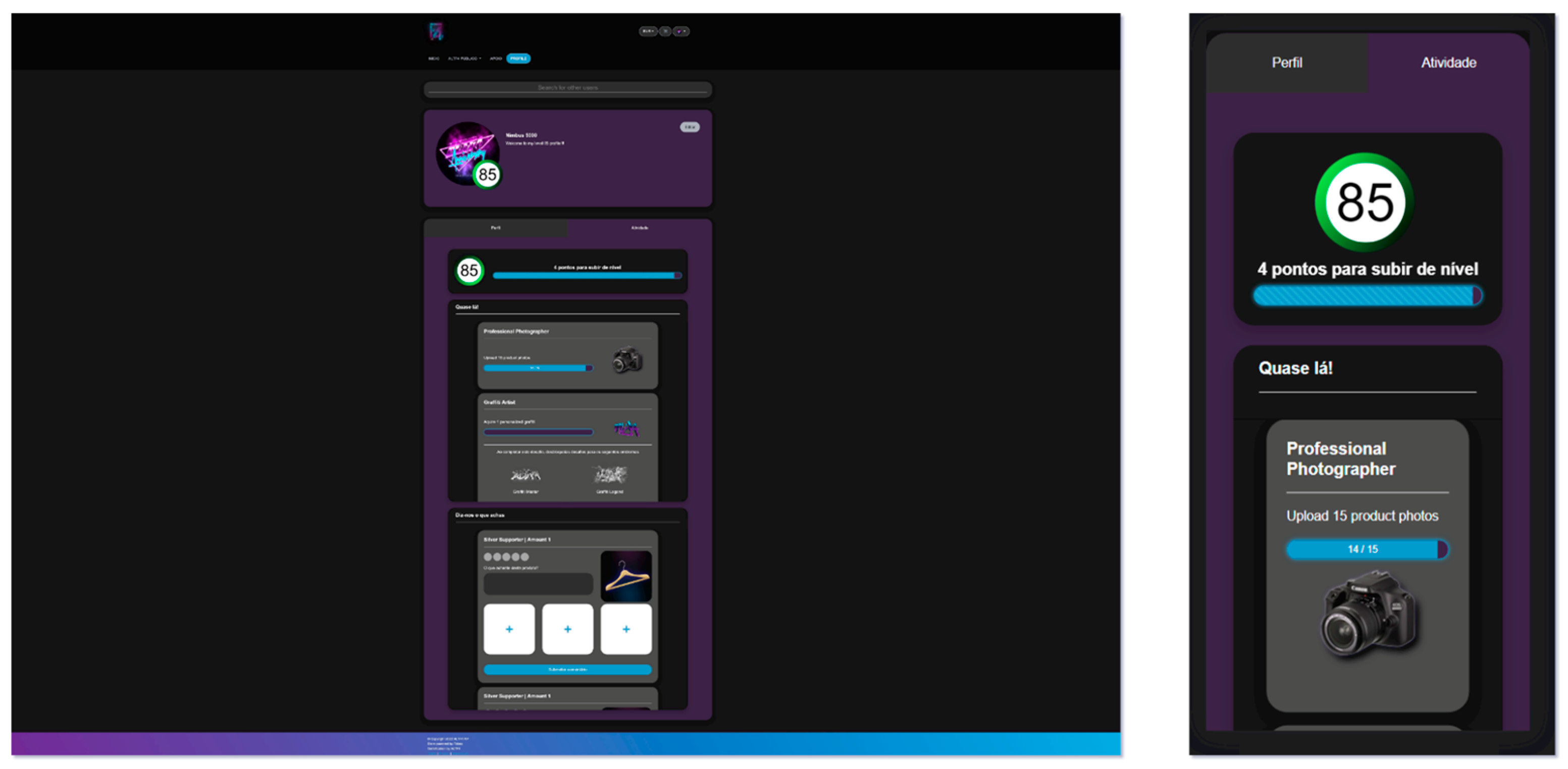

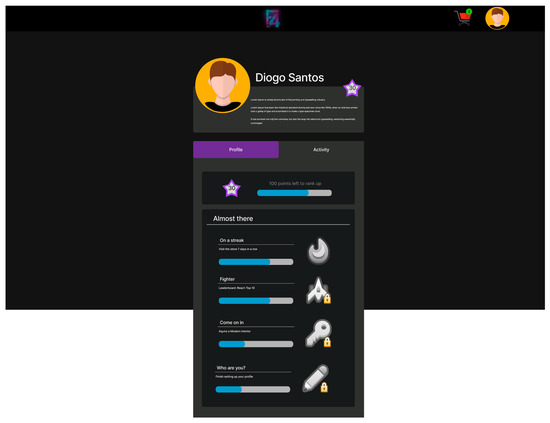

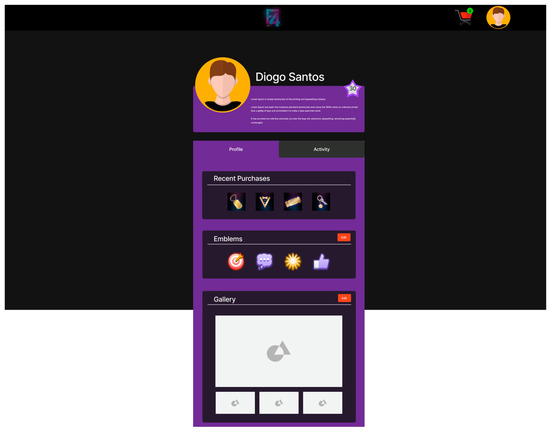

Figure 8 displays some challenges created following this framework, as well as a view of the developed prototype where a user can see the overall progress. This page is only visible if the profile belongs to the user. The “Activity” tab shows the user the points needed to reach the next level. It also shows the challenges that he/she are currently in the process of completing and the badge he/she will receive at the end.

Figure 8.

User activity view.

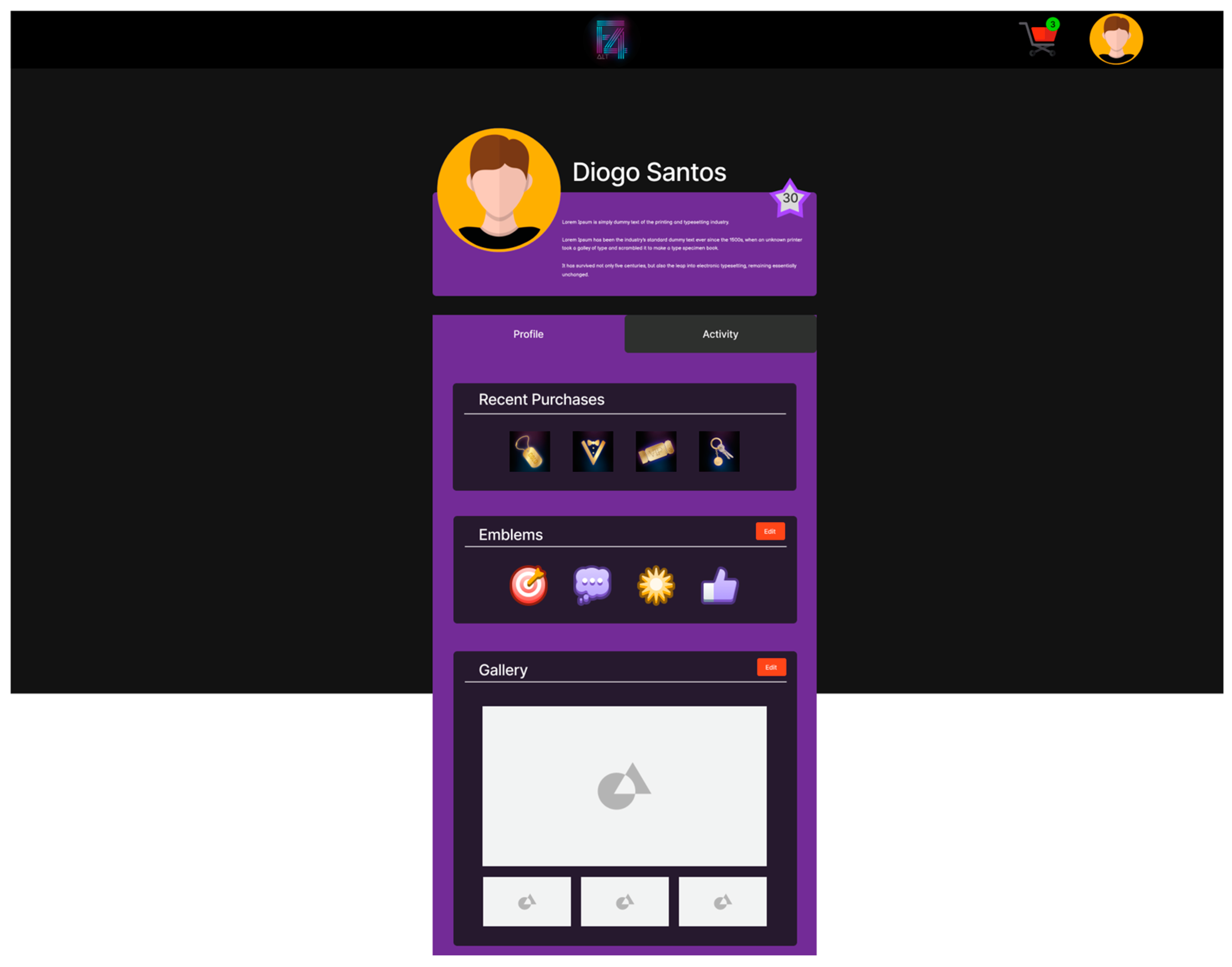

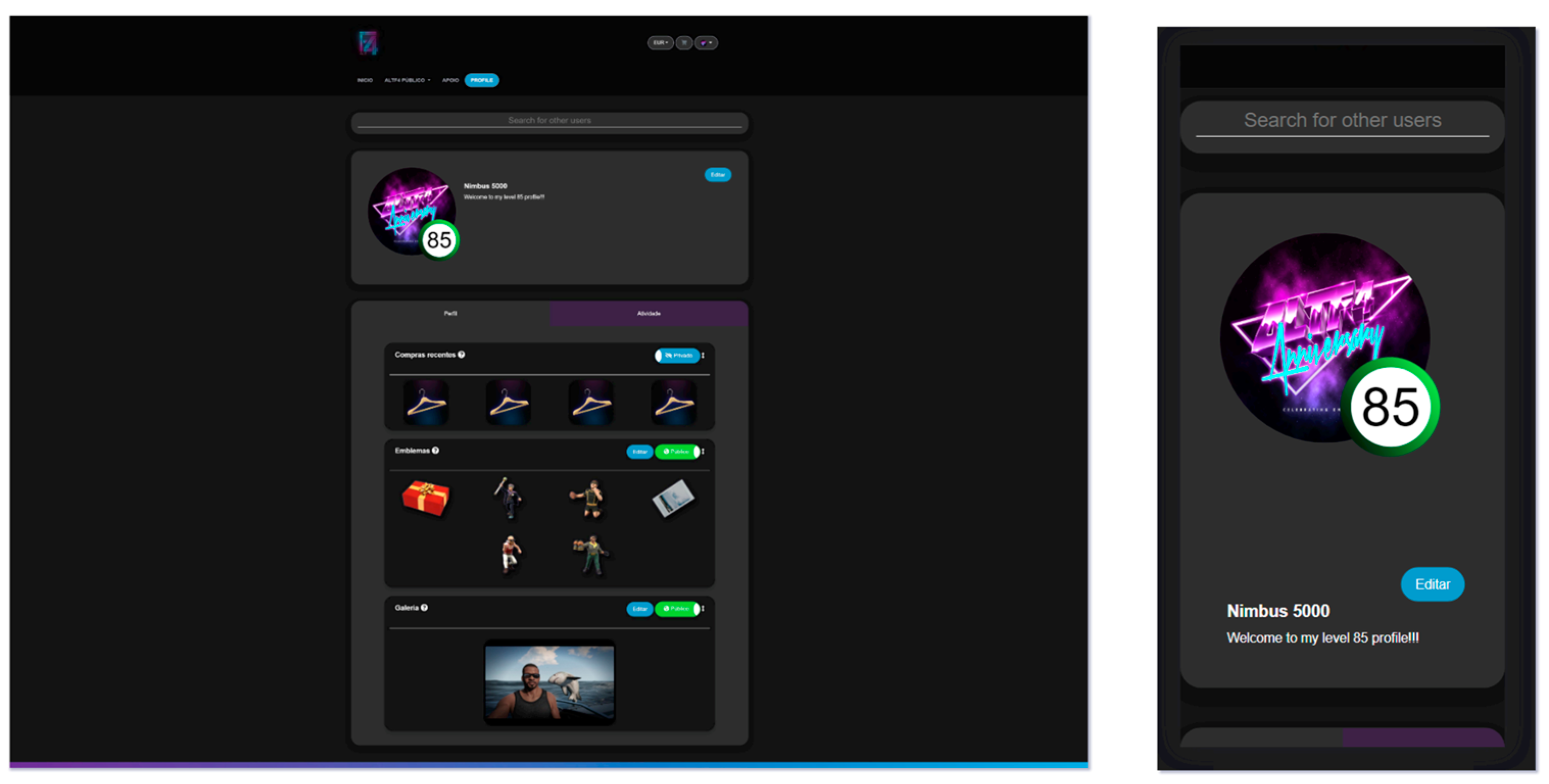

Figure 9 shows the profile page of a user, which can be customized and is also visible to other users. It consists of a profile picture, username, current level, and a short biography. Underneath there are three categories that the user can choose to show or hide:

Figure 9.

User profile view.

- Recent purchases—showing recently purchased products.

- Badges—the user can choose four badges to show out of the set of badges he/she has already received.

- Gallery—the user can choose, from the images attached to the product reviews he/she has made, a selection of images to display.

This design was inspired by the user profiles of Steam (https://steamcommunity.com/ (accessed 15 September 2022)), a shop and a distribution platform for digital games.

3.5. Test

With the prototype completed, 10 usability tests were performed, one for each participant, to evaluate the gamification concepts implemented. Each interview contained a list of tasks that each user had to complete. The users were asked to record the screen and encouraged to explain their reasoning aloud for later analysis. The users who carried out the tests were again selected from the group who agreed to share their contact details in the initial questionnaire. The usability tests were composed of 18 tasks (described in Table A1 of Appendix A) and intended to evaluate the different gamification concepts. To evaluate the tasks defined above, five metrics were identified for each task:

- Task completed—whether the user was able to complete the task.

- Duration—how long it took the user to complete the task.

- Number of errors—how many incorrect actions existed while the user was completing the task.

- Clicks—how many clicks it took for the user to complete the task.

- Confusion—how many times the user showed uncertainty or confusion while performing the task.

At the end, the user’s success was calculated using the following formula:

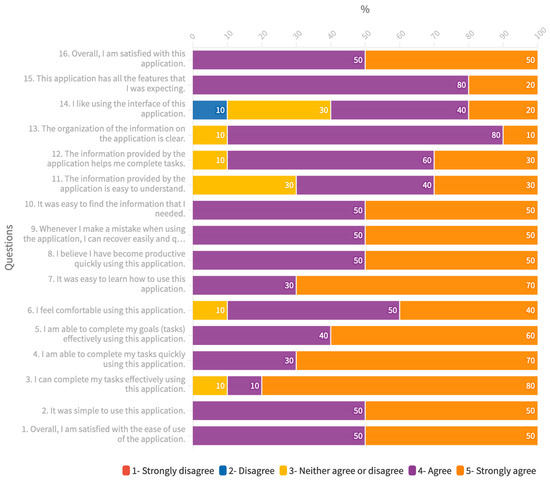

To evaluate the users’ satisfaction when interacting with the prototype, the users were asked to fill out an adaptation of the questionnaire Computer System Usability Questionnaire (CSUQ) [49], using a Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) [50] (see Table A2 in Appendix A).

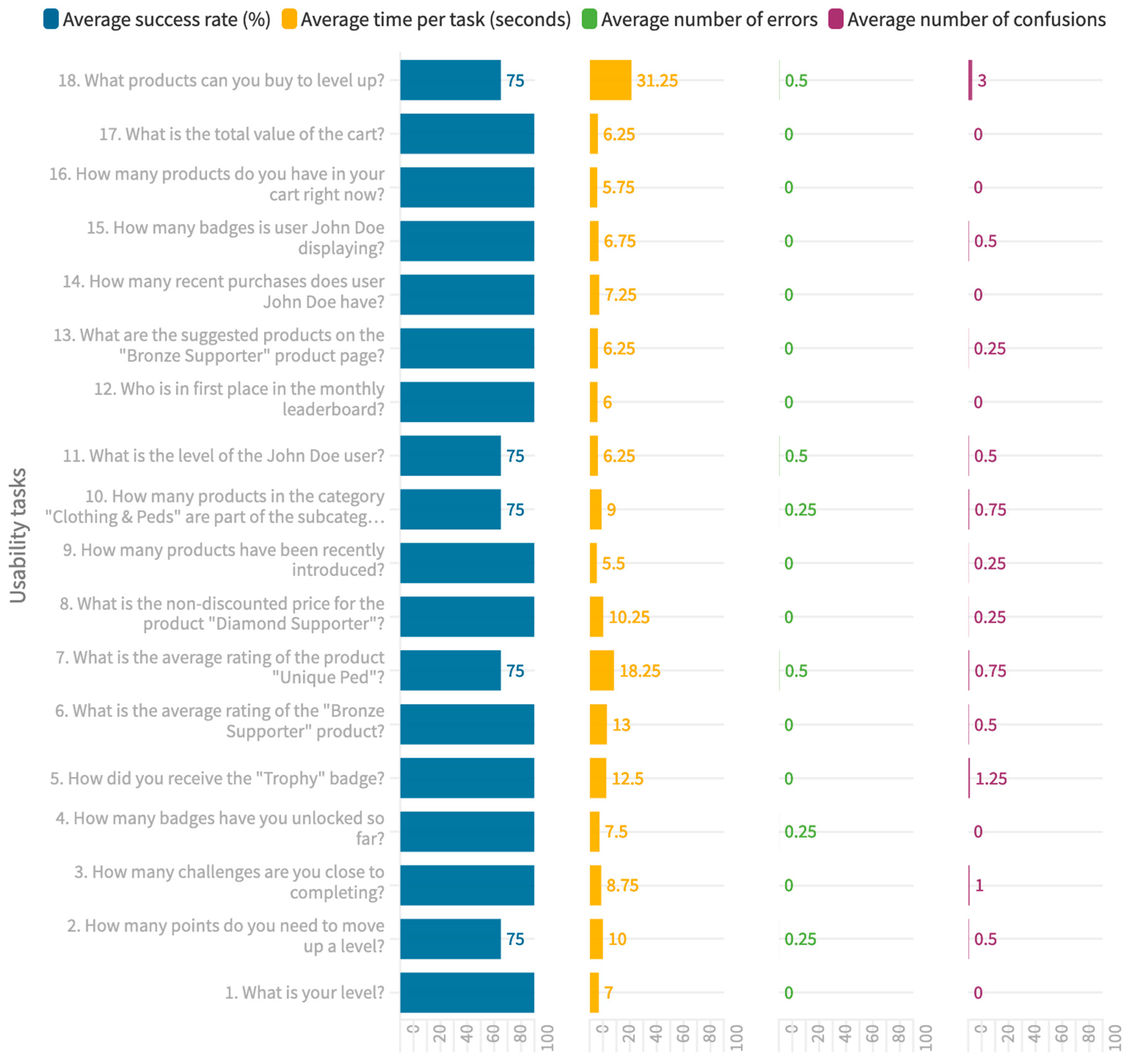

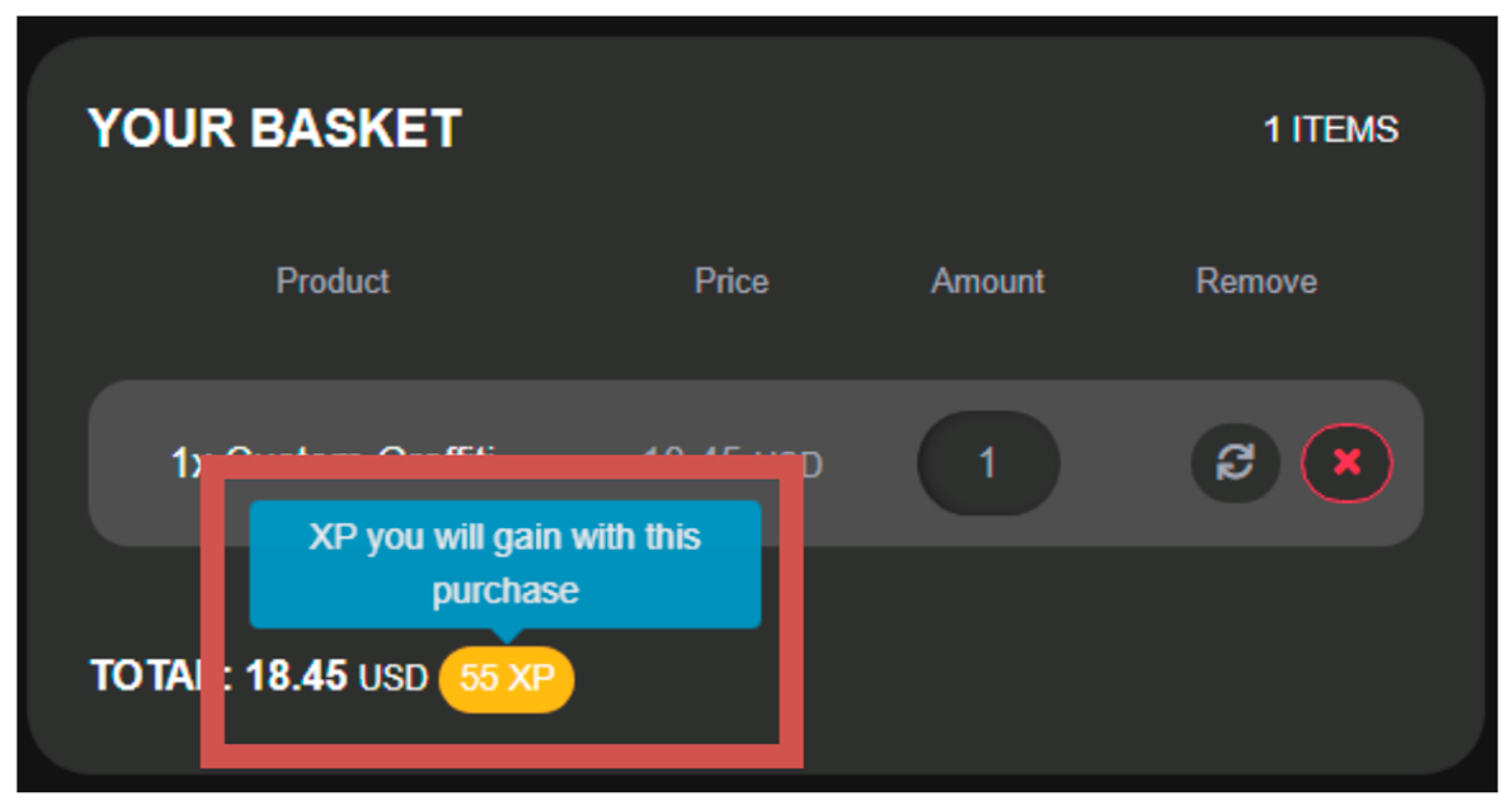

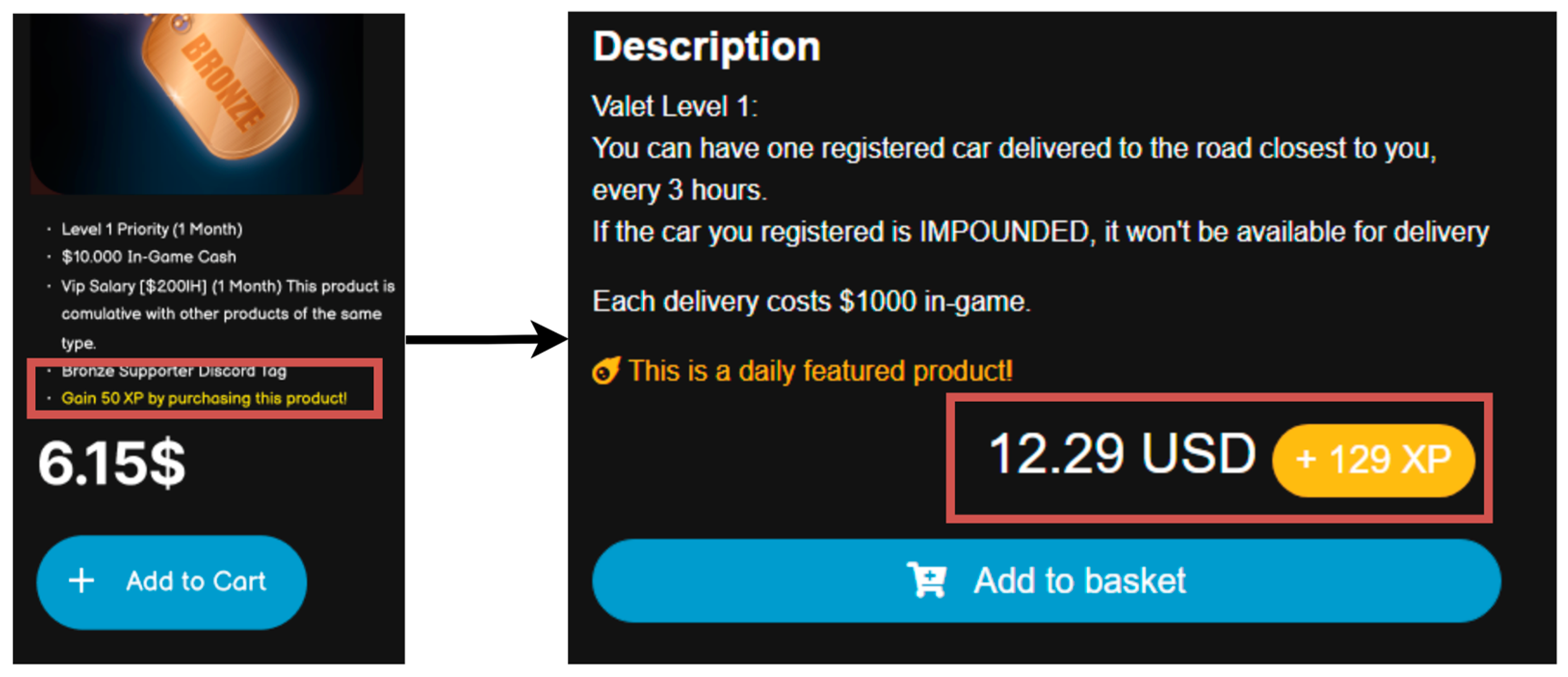

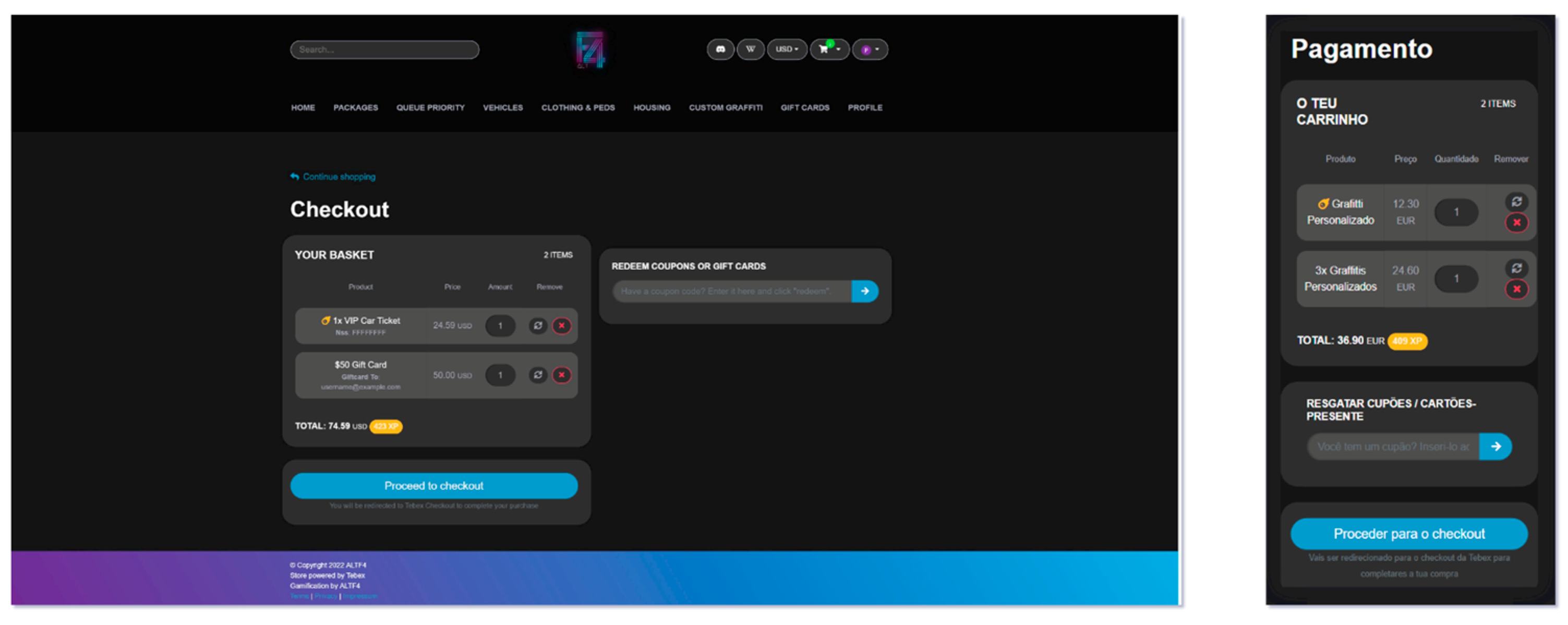

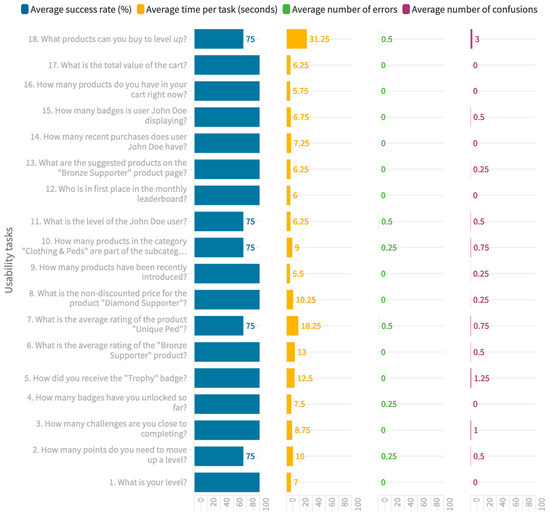

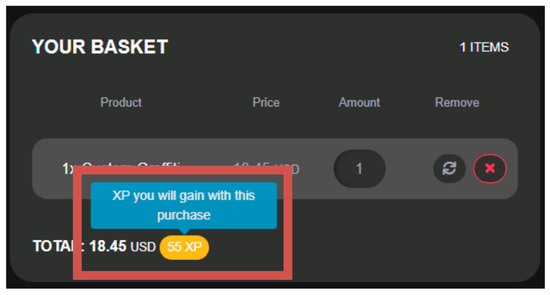

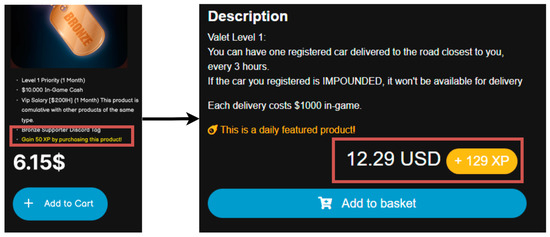

Of the 18 tasks asked, the last one generated the most doubt and took on average the longest time to answer (see Figure 10). This task asked the users which product they could buy to level up, and although the answer was available on the product page, it was not visible enough. This difficulty was important to implement improvements to facilitate the usability of gamification strategies, as shown in Figure 11 and Figure 12.

Figure 10.

Metrics of the usability tests.

Figure 11.

Checkout page with changes.

Figure 12.

Changes on the product page.

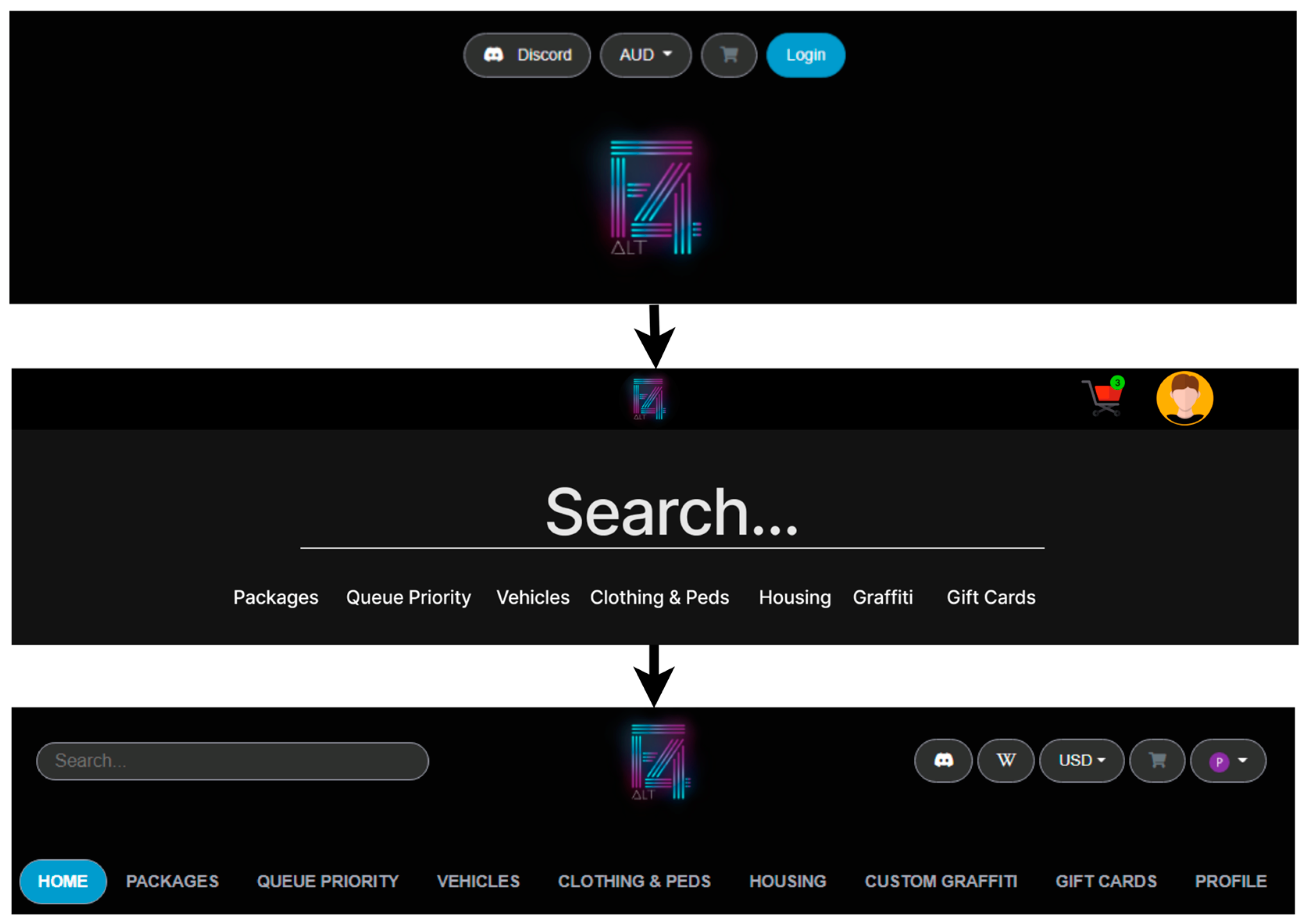

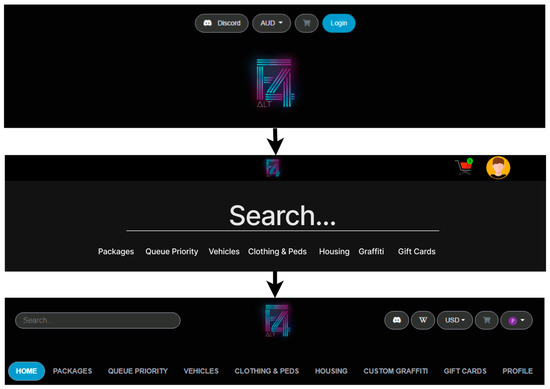

The users expressed dissatisfaction with the search bar and category list being too large and taking the focus away from the products, thus forcing users to scroll every time they enter the shop. The search bar and category list were then reduced in size and added to the shop header (see Figure 13).

Figure 13.

Changes to the header of the store.

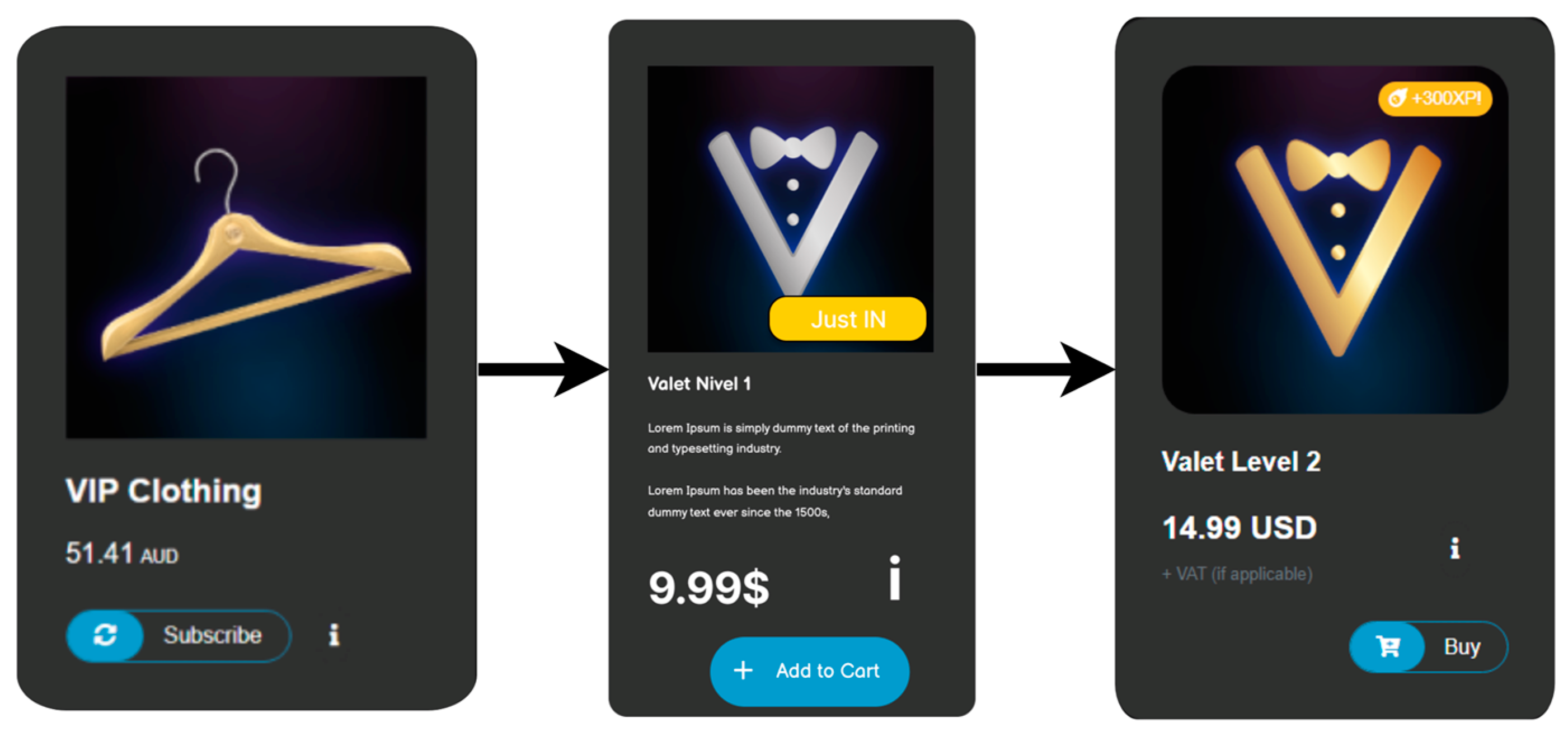

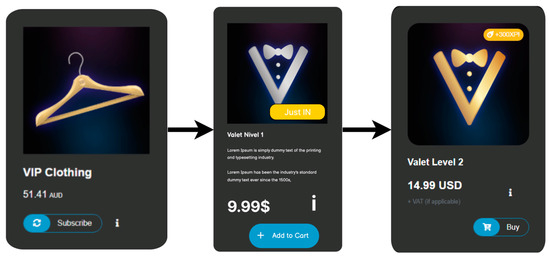

Based on the information gathered through the comments regarding features that the users would like to see on the store interface, it was possible to conclude that a significant number of users mentioned the possibility of purchasing a “Just In” product offering extra experience points. Consequently, the “Just In” label was replaced with a daily assortment of featured products that give users more experience points if purchased that day (see Figure 14).

Figure 14.

Changes on the product page.

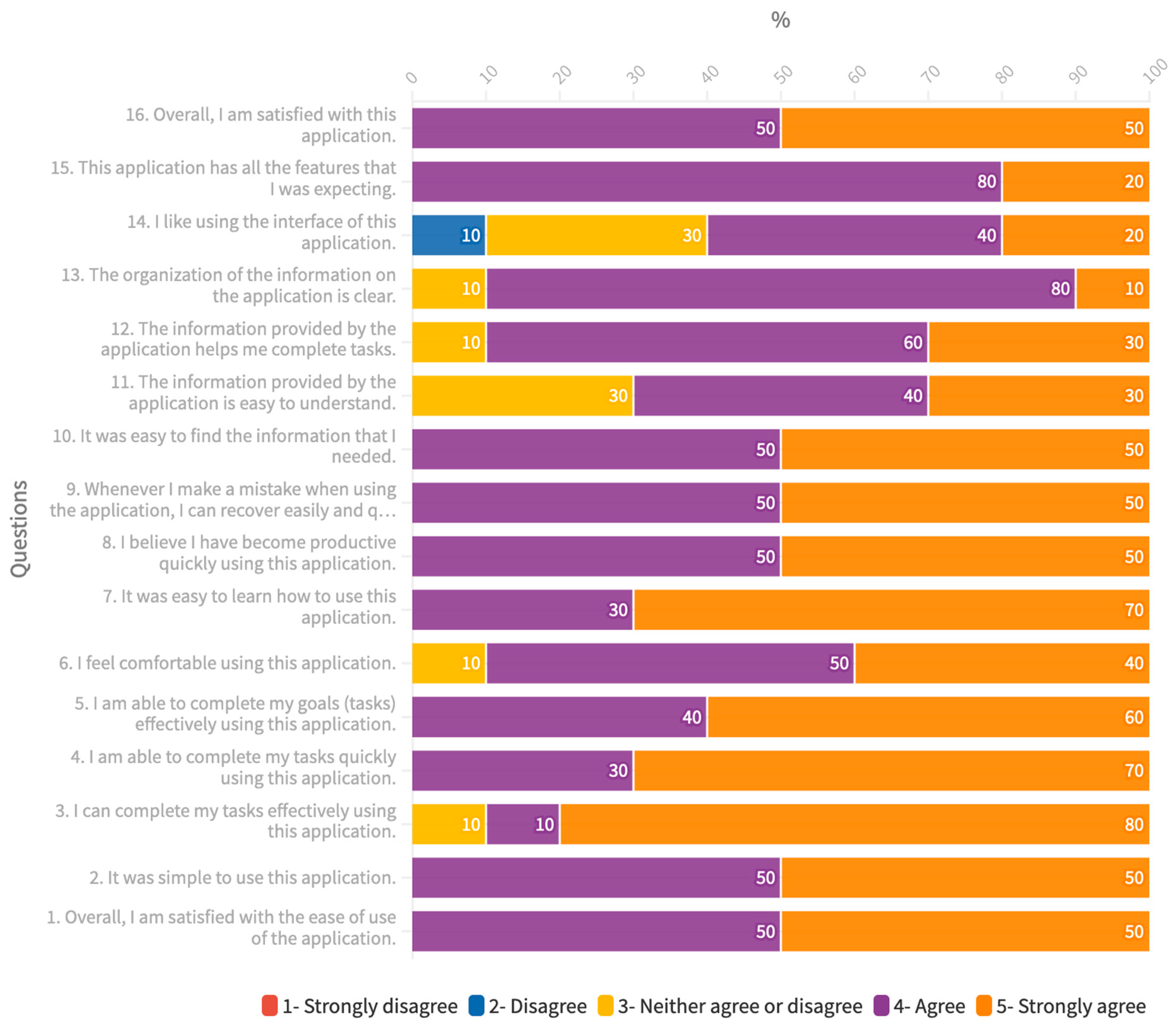

Regarding the usability questionnaire, the results were encouraging since the users’ answers validated the developed prototype (see Figure 15). Most users strongly agreed or agreed with the all the questions, except for question 14: “I like using the interface of this application.” In this question, 1 out of 10 users (10%) did not like using the interface. We believe that this was mainly because the prototype was still not applying the color palette of the store.

Figure 15.

Usability questionnaire results and average rating per question.

3.6. Implement

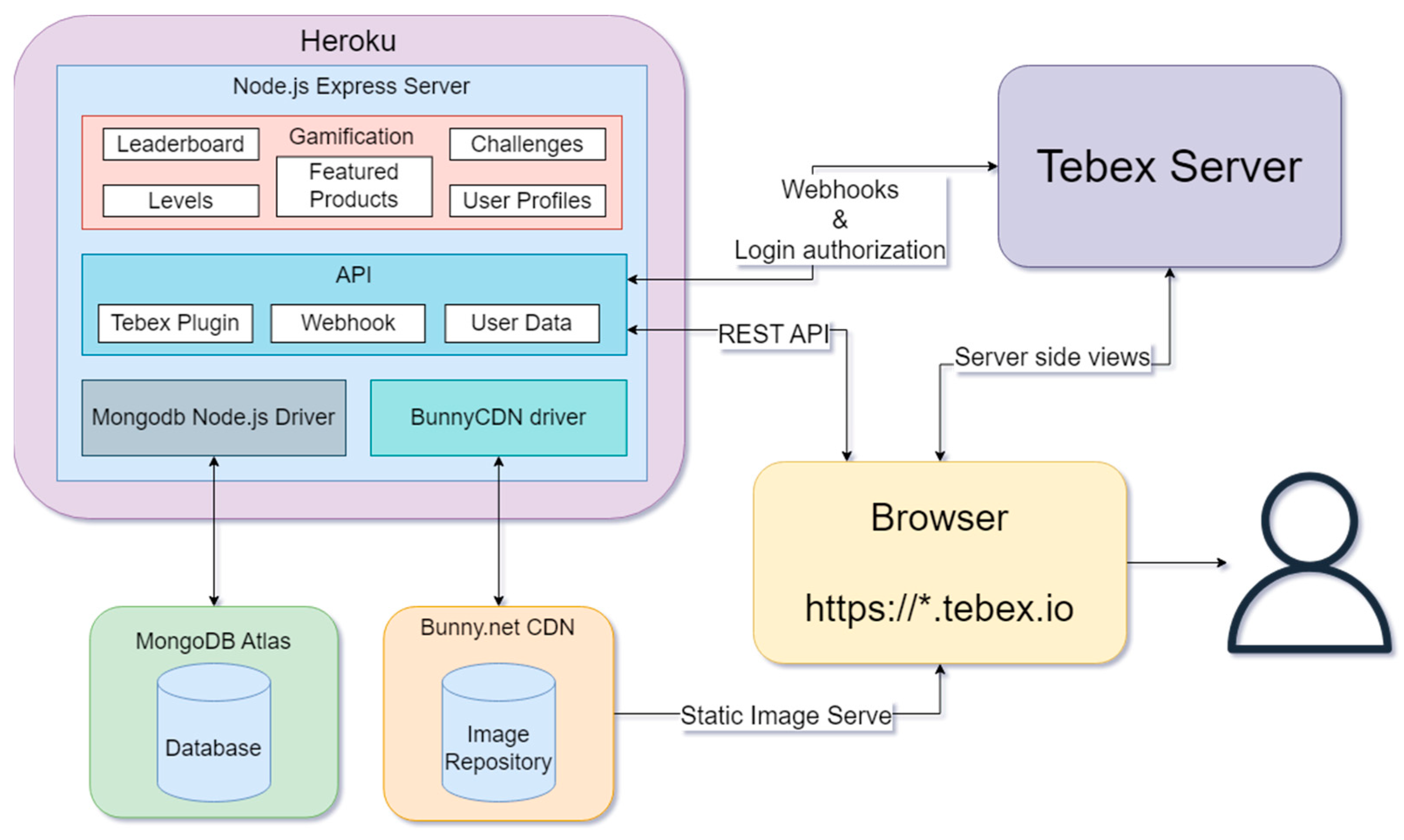

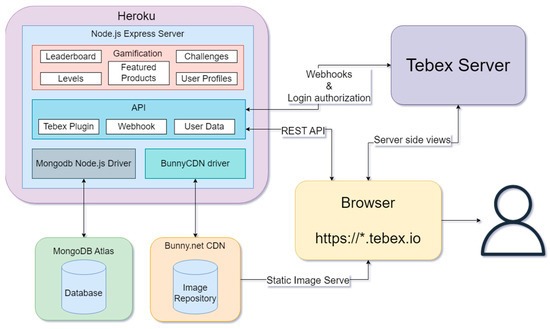

After the validation of the prototype through the usability tests, we proceeded to the implementation of the server that supports the gamification concepts. A server and a database were implemented for each store due to the large geographical distance between the two communities, with the purpose of reducing the response time of requests and to keep the data of the two stores separate. Through Heroku (server hosting platform), the servers were hosted in the US and Ireland. The prototype was implemented, and an external server was developed to handle the gamification data. The data exchange was performed using a REST API (see Figure 16).

Figure 16.

Diagram overview of the implemented application.

As seen in Figure 16, Tebex is responsible for processing payments for the stores and where the stores are currently hosted. Tebex provides an API to obtain information about the products displayed in the stores, payments made, and user information. All stores are hosted on the subdomain (https://www.STORE_XPTO.tebex.io (accessed on 27 February 2023)), and upon payment, users are directed to the next common subdomain where payment is made (https://checkout.tebex.io (accessed on 27 February 2023)) which is outside the stores’ control. The API that Tebex provides has an endpoint to generate a checkout URL, but it is for the store subdomain and not for the checkout subdomain. Thus, developing a store external to Tebex is currently not possible without significantly affecting users’ final experience. However, Tebex provides the source code used in the stores, which allows the implementation of the validated prototype.

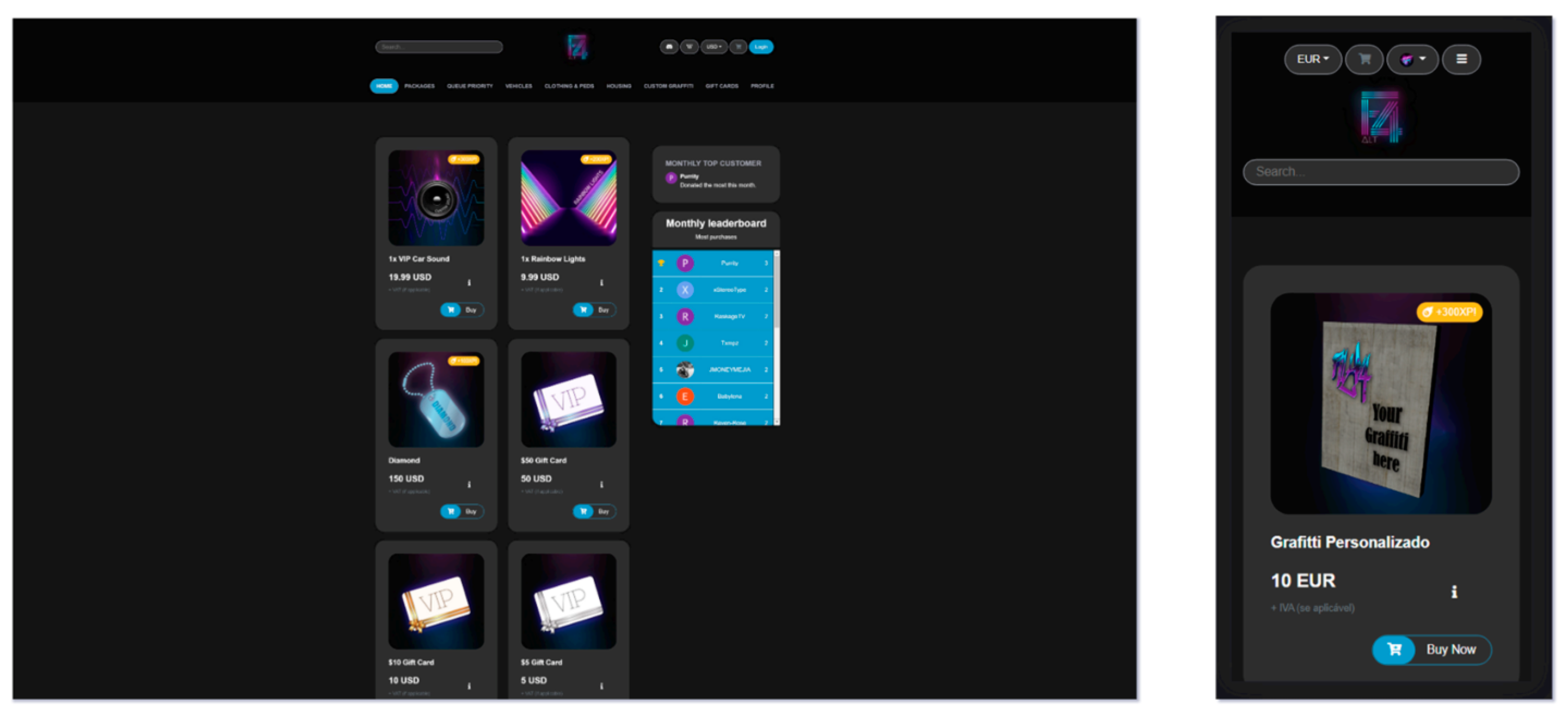

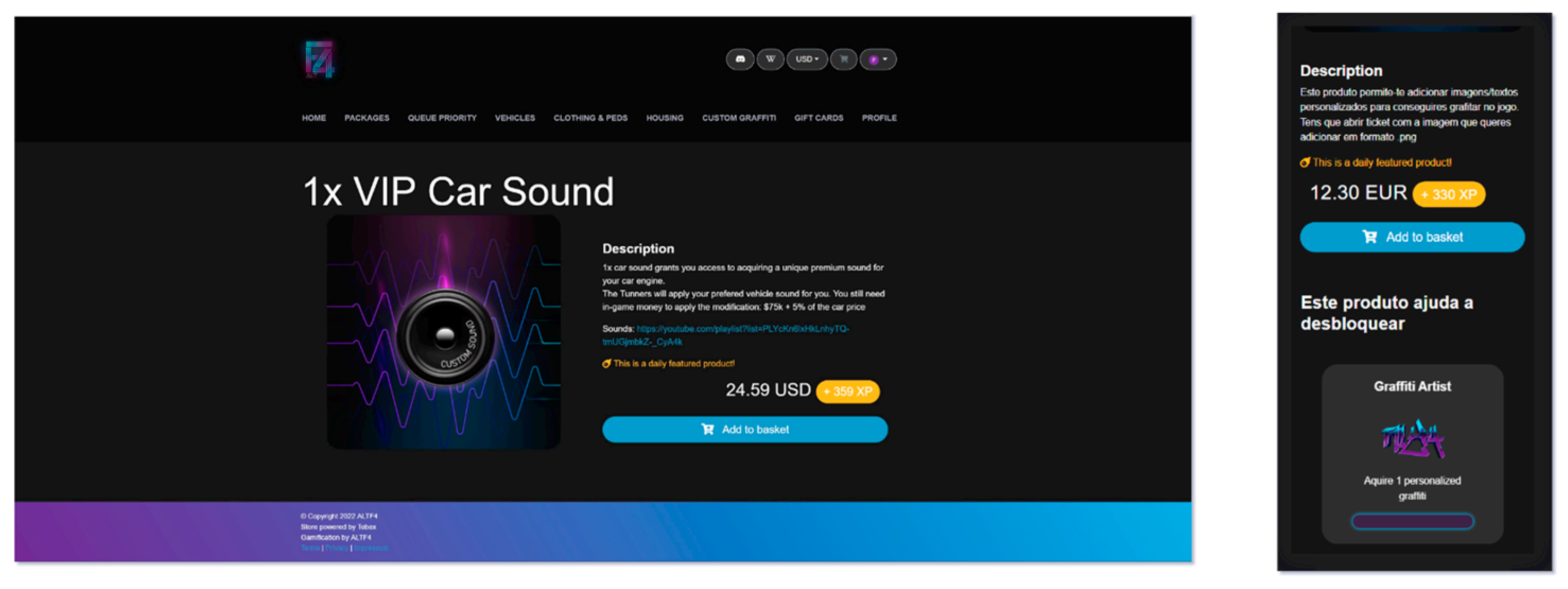

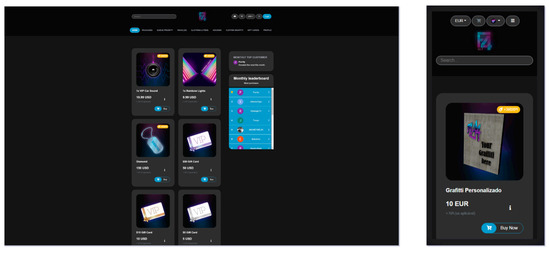

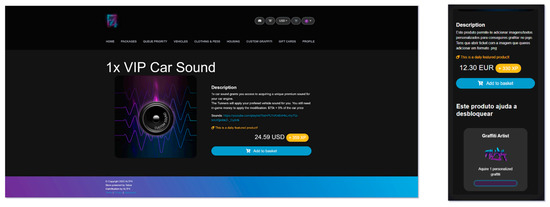

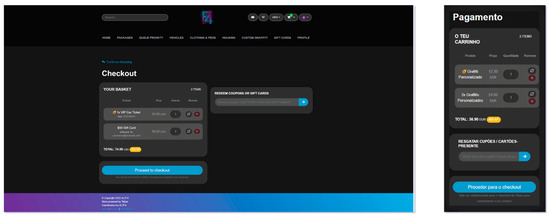

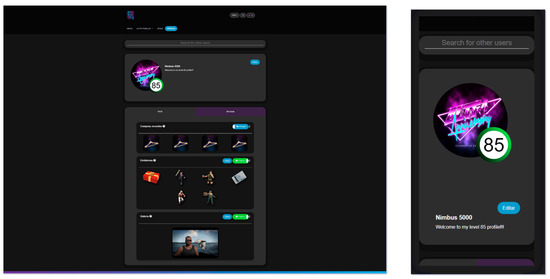

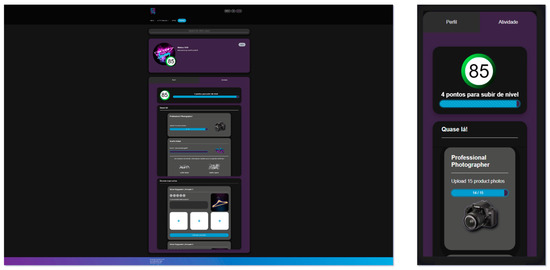

For the development of various screens, the frameworks used by Tebex were employed, namely Bootstrap, JQuery, and JQuery UI, in order to not increase the number of dependencies and consequently the time it takes for the page to load. In the modified screens, the responsiveness of the various elements is maintained so that the stores can be addressed on a wide selection of devices, particularly mobile devices (see Figure 17, Figure 18, Figure 19, Figure 20 and Figure 21, in which a desktop view is presented on the left side and a mobile view is presented on the right). According to Statista [51,52], online shopping on mobile devices will be more than 50% of the total number by 2022.

Figure 17.

Main page: desktop view (left side) and mobile view (right side).

Figure 18.

Product page: desktop view (left side) and mobile view (right side).

Figure 19.

Checkout page: desktop view (left side) and mobile view (right side).

Figure 20.

User profile page: desktop view (left side) and mobile view (right side).

Figure 21.

Activity page: desktop view (left side) and mobile view (right side).

With these limitations, the server only functions as a REST API, providing a means of communication between clients accessing the site and the gamification resources they wish to obtain. It was developed in Node.js, which allows it to keep the programming language uniform when developing both front-end and back-end codes. The REST API is responsible for authenticating users and validating that they have access to the resources they request. To assist in the development of the various routes and HTTP methods required, the Express.js framework was used. Authentication is a mandatory requirement to ensure that information has not been altered or improperly accessed. To complete this requirement, the thejsonwebtoken module is used to generate two tokens with a user’s information at the login time sent as a response to be stored on the user’s device and to be sent at following requests. One of the tokens expires after one day, and the second one with no expiration time is stored in cookies as httpOnly and cannot be accessed on the client side by Javascript. Payment information is received via a request sent by Tebex to an endpoint on the server containing the associated payment information. To verify the authenticity of the requests, the verification advised by Tebex is followed so that only authentic requests are accepted. To store various user, product, and gamification information, MongoDB was used, chosen for its flexibility in storing data without being constrained by a schema. To improve server performance, the badge icons and profile images uploaded by users are uploaded to a CDN (Content Delivery Network).

3.7. Evaluation

In the evaluation phase, three metrics were used to evaluate the effectiveness of gamification in an e-commerce context. A user survey was made available through the store to gather data on the interaction between users and gamification elements, and store revenue.

The survey was based on Pedroso et al. [53] and adapted to fit the context of online commerce and collect users’ opinions about their in-store experience. After two weeks, from 23 September to 7 October 2022, the survey had 106 responses on the US server and 32 responses on the PT server. The results obtained are shown in Table 8.

Table 8.

Results of the online questionnaire on the impact of gamification application on users.

The ages of the users on both servers are mostly concentrated between under 18 and 18–24, with some outliers being over 35 on the US server. These users are mostly male, with the US server having a slightly higher percentage of female users (29% versus 16%).

Regarding the first question (Table 8), on both servers, the general opinion was divided between “Less than I expected” and “Exactly what I expected”. This is in line with the feedback given at the end of the survey where some users indicated that the buttons to access the profile page were not highlighted enough.

On the US server, more than half of the users said that gamification improved their in-store experience (66%) and felt that they returned more often to the store because of the concepts implemented (64%). The users on the PT server had a similar opinion (54%).

When it came to purchasing products to complete challenges, there was a greater contrast between the two servers. While 66% of the users on the US server responded that they would purchase a product to complete a challenge, only 17% of the users on the PT server would do so. The reasons for these responses were revealed in the questions that followed, where 81% of users on the PT server revealed they were not interested in badges, while slightly more than half of the responses on the US server (57%) admitted to not liking the badge they would receive. Of the users who would be willing to purchase a product to complete a challenge, the main motivations were displaying the received badge on their profile for other users to see (45% on the US server) and that the product would eventually be purchased (43% on the PT server).

Finally, 42% of users on the US server and 54% of users on the PT server mentioned that gamification was not a distraction because it was optional, while 50% and 37%, respectively, felt positive effects. A small proportion (8% and 10%, respectively) preferred not to have gamification introduced.

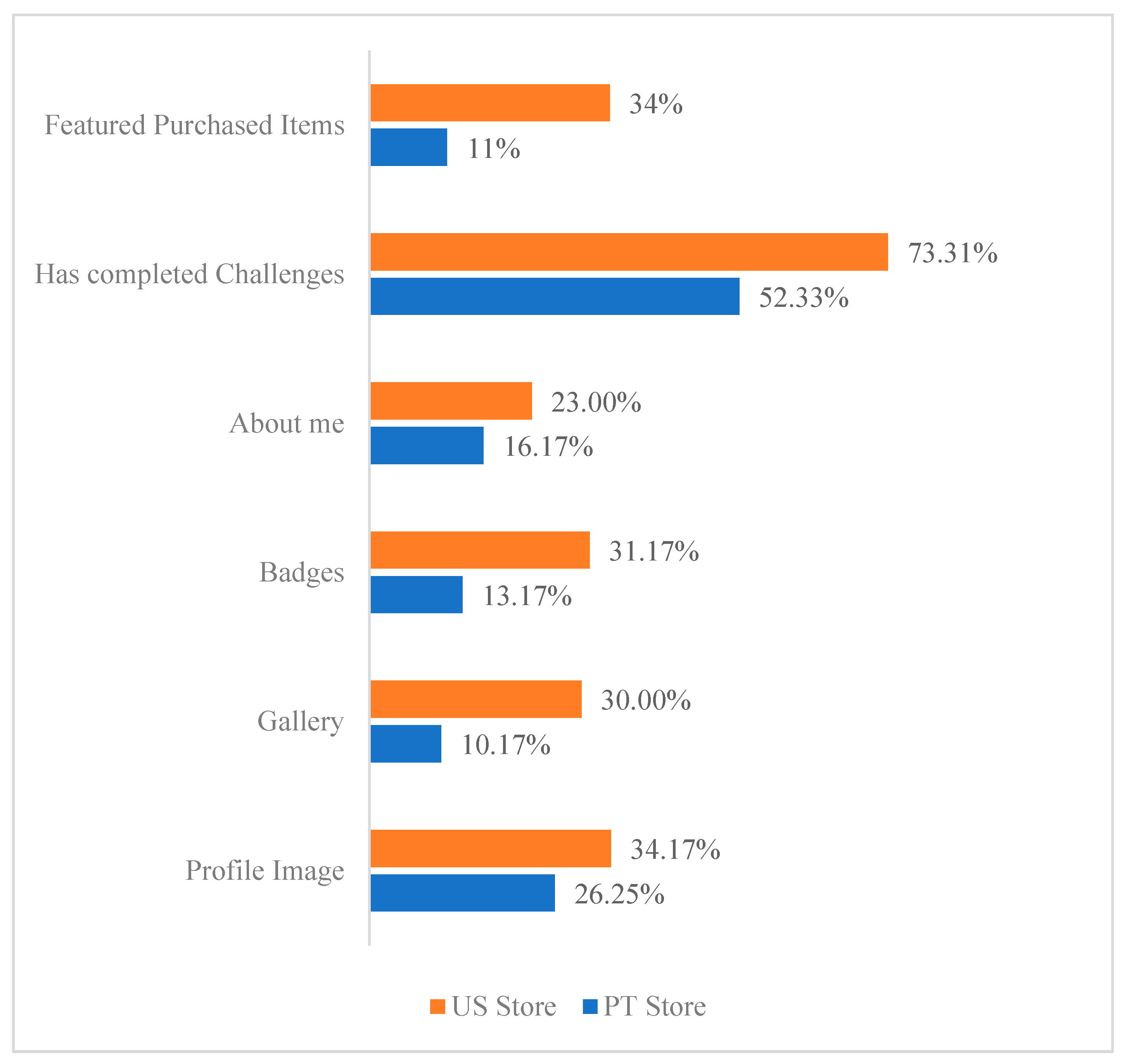

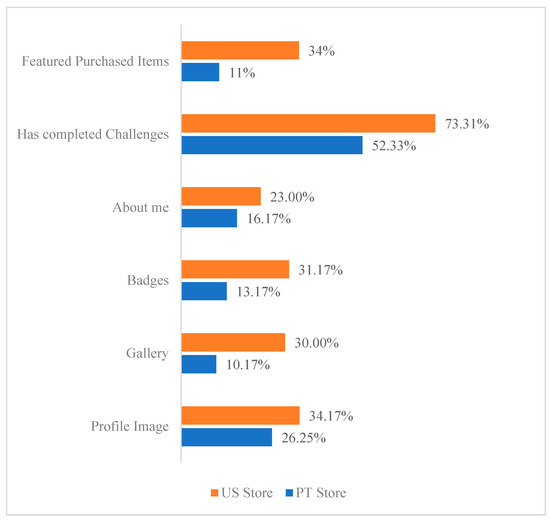

Indicators for the analysis of the use of gamification concepts were extracted from the databases (see Section 3.6). The indicators collected show the interaction of users with their profile page and with the functionality of the highlighted products. On both servers, there was an interest in the gamification concepts, but on the US server, there was clearly more interaction. The first two metrics in the “Usage Indicators” graph (see Figure 22) do not depend on direct user input and are only for reference as they are not definitive indicators. The remaining indicators do not depend on direct user input. The description and profile picture are what users see first and can change without prerequisites. Badges, on the other hand, require challenges to be completed, and the gallery requires images to be submitted along with reviews of purchased products.

Figure 22.

Usage indicators with the gamified concepts per store.

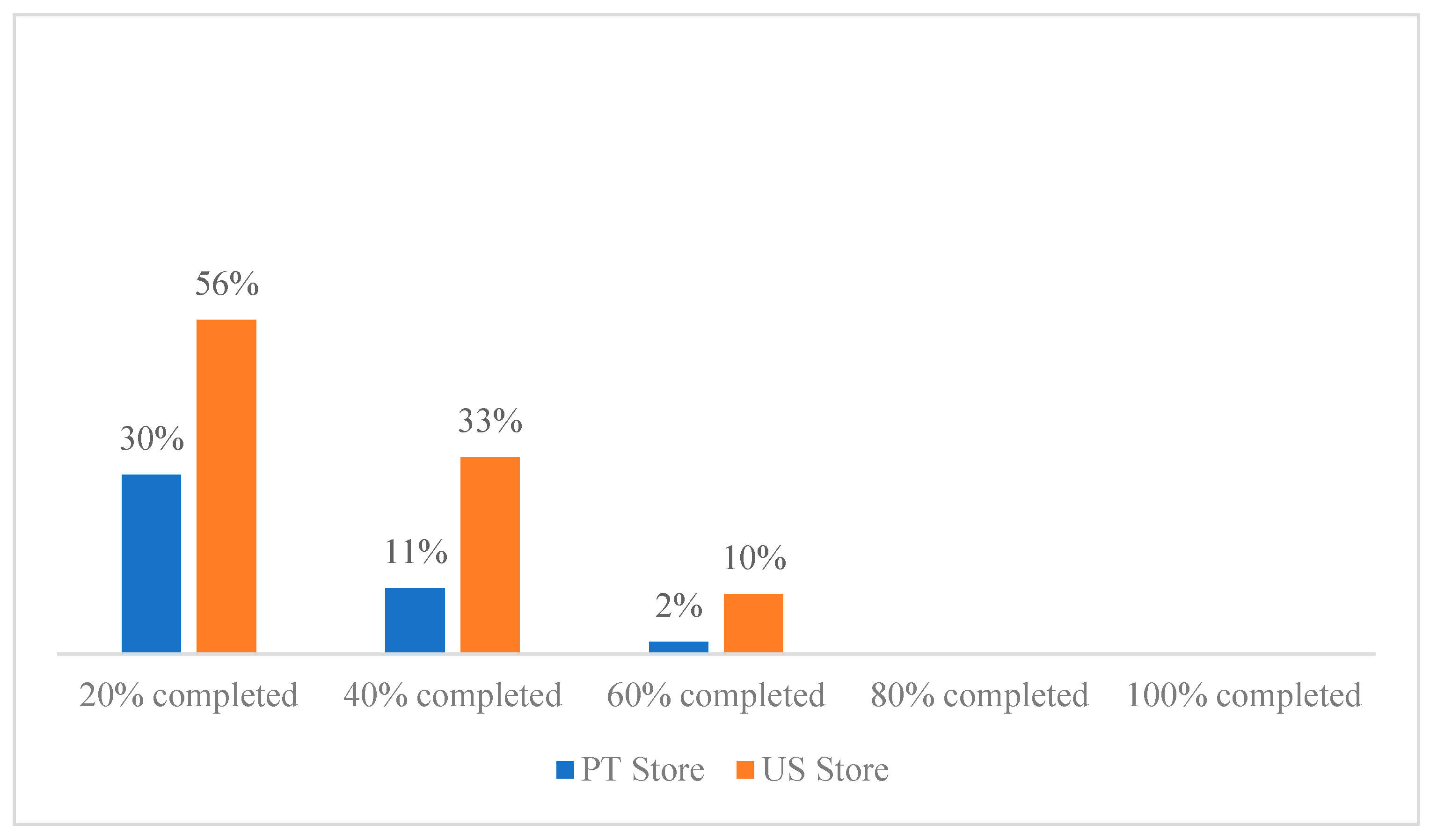

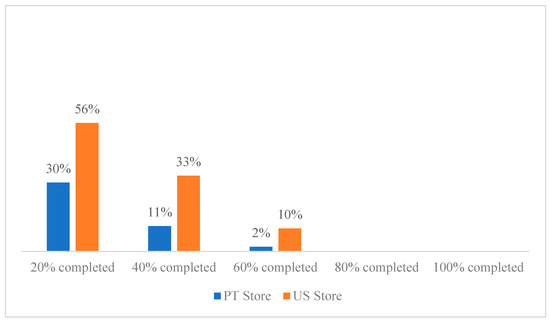

The graph of completed challenges describes the percentage of users on both servers that completed 20, 40, 60, 80, and 100% of the challenges (Figure 23). The challenges were created on a large scale, so it was not expected in the established evaluation period that a user would achieve a 100% completion rate. Even so, the number of users with the most challenges completed was higher in the US store.

Figure 23.

Percentage of users who completed challenges by store.

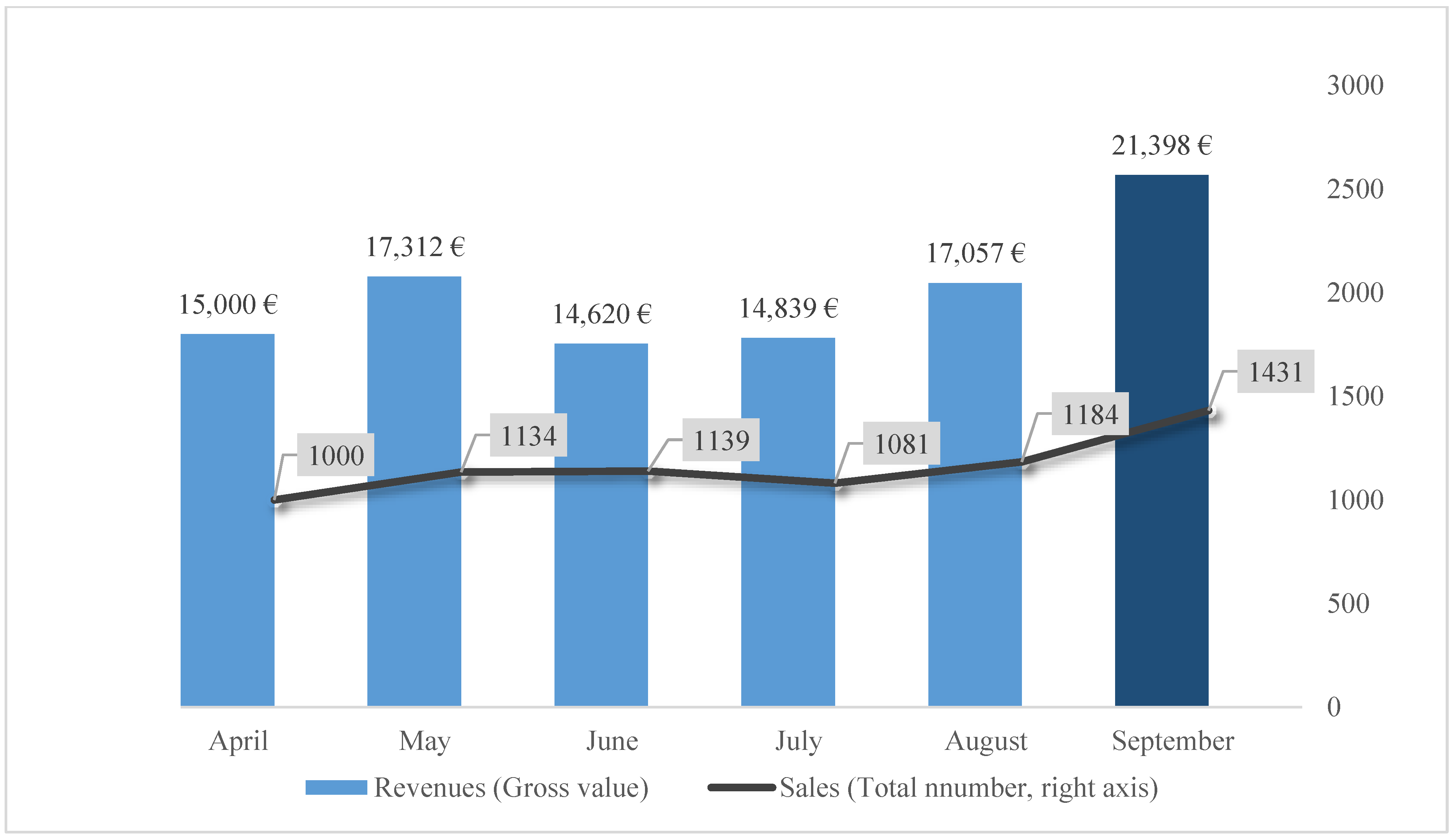

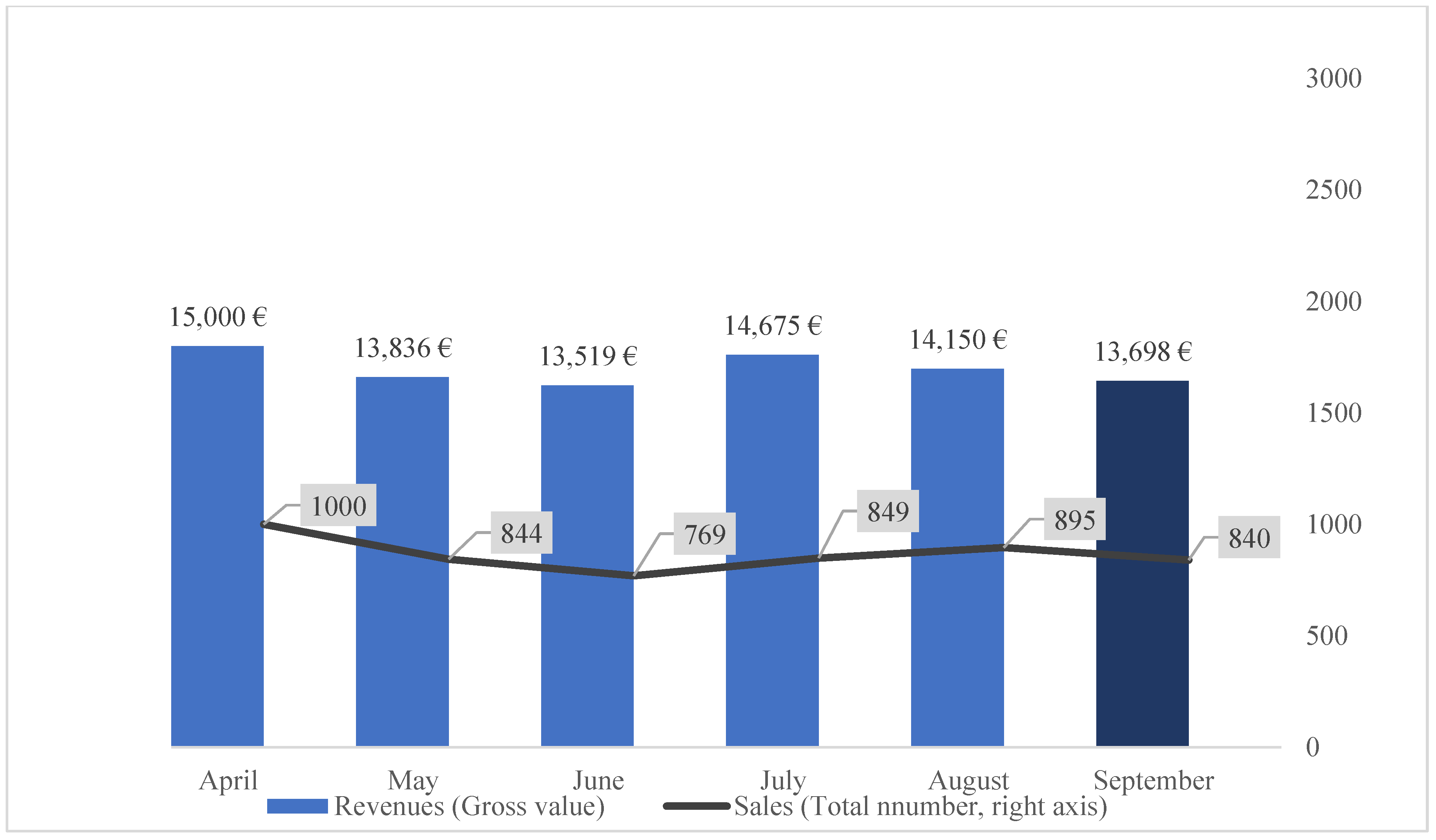

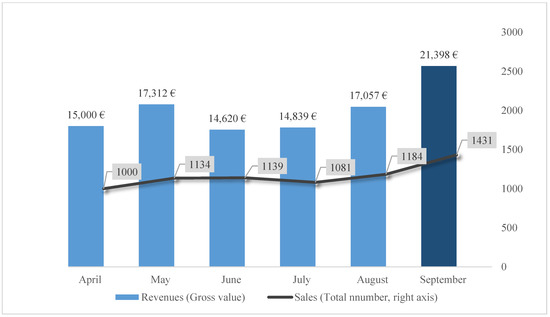

Finally, the change in store revenue was analyzed by comparing the revenues in the month the gamification concepts were implemented, i.e., September, versus the previous five months. We were only provided the percentual change for the gross revenue and number of sales, so the values of EUR 15,000 and 1000 units were purely used as a starting point. There was a significant increase in revenue and number of sales in the US store (as displayed in Figure 24) when compared to previous months. In the previous five months, the maximum increase was 15%, and in the month in which the store was gamified (highlighted in the graph in darker color), there was a 25% increase in revenues and the number of sales increased by 21%. Since there was also an increase in the previous month, we cannot say with certainty that this increase was completely due to the implementation of this project.

Figure 24.

US shop: evolution of revenues (sales volume) and total number of sales from April to September 2022.

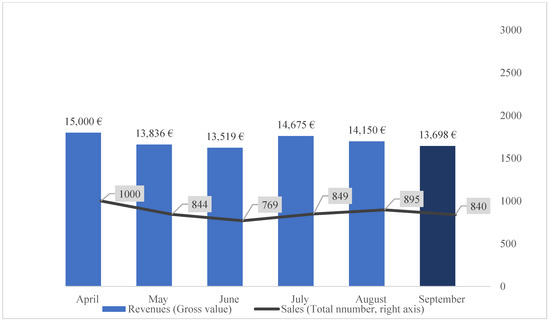

Regarding the PT store, no significant differences were noted (see Figure 25), since in the month of April, the percentage difference varied between −10% and 10%. In the month of September during the implementation of the prototype (highlighted in the graph with darker color), there was a 3% decrease in store revenues and the number of sales decreased by 6%.

Figure 25.

PT shop: evolution of revenues (sales volume) and total number of sales from April to September 2022.

From the analysis of the questionnaires, we found a larger group of teenagers on the PT server compared to the US server. These younger users showed little interest in completing challenges and obtaining badges on the PT server, while on the US server, these elements were given greater importance so that such achievements could be shown to the rest of the users. In the context of online commerce, a lower purchasing power presents a greater difficulty in interacting with certain elements of the gamified system. For the PT store, the introduction of some discounts as rewards may be beneficial to gain interest in the system. A more intrusive and less optional gamification could also help correct this shortcoming; however, from the beginning, users expressed the need for choice, so this approach was not explored. In the US store, which is visited mostly by adult users, there is less need for discounts, so the value assigned to badges (social and personal) is higher. These results are in line with the findings reported by Meder et al. [54], in which tangible rewards can motivate users more than intangible rewards.

Since it is also a roleplay server, it is normal that the elements that had the most impact on the users were the profile customization and the leaderboards since both promote interaction between users, although with different dynamics (social versus competition). All of these contributed to the apparent positive effect on the business of the US store and the satisfaction of its users.

The users of the PT store also reported being satisfied with the introduction of gamification, but its revenues remained similar to previous months. Despite the positive results, in the one-month period available, it is not possible to ascertain whether the effectiveness of the gamified elements remains constant in the long term, especially since the motivation offered by gamification tends to decrease over time [55,56].

Regarding the research questions, there are no indications to prove that certain elements cannot be used, but the elements that seem to be more successful are the ones that satisfy the types of players that play on the server that the store supports. In this implementation, which attempts to assign value to intangible rewards, the users of the US store were more receptive to these types of rewards than the users of the PT store. Thus, gamification seems to have a positive effect on business if the above-mentioned aspects are considered.

This work implemented gamification that rewarded primarily with badges and extra customization on user profiles through extra spaces for photos and badges as incentives to level up, rather than monetary rewards, whenever possible. This decision might have had some impact on motivating some users to interact with the gamification elements, but the goal was to create value in non-monetary rewards; otherwise, the results might be considered “contaminated” since each reward results in a discount.

4. Conclusions

In this paper, we presented a gamification process and how it affects both customer satisfaction and store revenues. Using the design thinking method, a new interface for the stores was presented and developed. An external server responsible for processing the various gamification concepts was also implemented. It was designed, developed, and tested through an iterative process, and provided answers to the research questions initially defined.

The evaluation phase was conducted through an online survey on both servers (PT and US), collecting data from the interaction between users and the gamification elements, and comparing the store revenues. The number of respondents of the online survey was not large, and, therefore, the findings are mere indicators of the behavior of both user populations.

After analyzing the results obtained in this study, we conclude that the use of this type of strategy is efficient for the business of the US store, with a significant increase in revenues. The work developed also reveals that gamification is well received in both stores, the one supporting the US server as well as the one supporting the PT server. However, on the PT server, despite the good reception, there was no significant increase in revenues obtained. These findings reveal that, although the store design process paid special attention to users’ needs, involving them at all stages, and the gamification elements were developed to attract the largest number of different types of players, cultural (geographic group) and demographic components play a determining role in user interaction with the gamified online stores.

Gamification continues to be adopted by more and more businesses to attract consumers and promote their return through unique experiences. The findings suggest a need for research into how users’ cultural environment affects the performance of gamified businesses and how the gamification design process can be adapted. These variables, including cultural and possibly socioeconomic differences, may provide the answer to consumer preference regarding tangible (discounts) and intangible (badges and user levels) rewards. A possible area of interest for future work would be the various ways to attract users. For those who prefer tangible rewards such as discounts, this type of gratification could be introduced at the initial levels, along with challenges to motivate interaction with the system, and then it could be switched later to intangible rewards.

A limitation to consider in this research project is that the continuous return of a user is not only dependent on the store, but also on his or her game experience within the respective server. Users who experience a negative situation and abandon the game are unlikely to return to the store. Due to the small data sample available for this research project, it was not possible to determine if the improvements in the US store and the amount of user engagement were due solely to the gamification elements applied.

Taking these findings and limitations in mind, a future action plan is to continue monitoring the impact of the gamification process for a longer period—six to nine months—and to apply the same questionnaire at the end of the period. A longer period will validate the results obtained in the first analysis and/or provide us with other variables that should be considered in a future round of implementation (for example, the ages of players may be directly connected with different type of gamification mechanics preferred) or reveal if the results presented here are only due to the novelty factor.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.S., E.C. and I.M.A.; methodology, E.C. and I.M.A.; software, D.S.; validation, D.S., E.C. and I.M.A.; investigation, D.S., E.C. and I.M.A.; data curation, D.S., E.C. and I.M.A.; writing—original draft preparation, D.S., E.C. and I.M.A.; writing—review and editing, E.C. and I.M.A.; visualization, D.S. and E.C.; supervision, E.C. and I.M.A.; funding acquisition, E.C. and I.M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is funded by FCT/MCTES through national funds and when applicable co-funded EU funds under the project UIDB/50008/2020, and with the support of the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT) through the funding of the R&D Unit UIDB/03126/2020.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data is reported in the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Usability test tasks.

Table A1.

Usability test tasks.

| # | Question |

|---|---|

| 1 | What is your level? |

| 2 | How many points do you need to move up a level? |

| 3 | How many challenges are you close to completing? |

| 4 | How many badges have you unlocked so far? |

| 5 | How did you receive the “Trophy” badge? |

| 6 | What is the average rating of the “Bronze Supporting” product? |

| 7 | What is the average rating of the product “Unique Ped”? |

| 8 | What is the non-discounted price for the product “Diamond Supporter”? |

| 9 | How many products have been recently introduced? |

| 10 | How many products in the category “Clothing & Peds” are part of the subcategory “Peds”? |

| 11 | What is the level of the John Doe user? |

| 12 | Who is the first on the Monthly Leaderboard? |

| 13 | What are the suggested products on the “Supportive Bronze” product page? |

| 14 | How many recent purchases does user John Doe have? |

| 15 | How many badges is user John Doe displaying? |

| 16 | How many products do you have in your cart right now? |

| 17 | What is the total value of the cart? |

| 18 | What products can you buy to level up? |

Table A2.

Usability questionnaire presented to the users after the test was completed.

Table A2.

Usability questionnaire presented to the users after the test was completed.

| # | Question | Answers * | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Overall, I am satisfied with the ease of use of the application. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2 | It was simple to use this application. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 3 | I can complete my tasks effectively using this application. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 4 | I am able to complete my tasks quickly using this application. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 5 | I am able to complete my goals (tasks) effectively using this application. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 6 | I feel comfortable using this application. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 7 | It was easy to learn how to use this application. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 8 | I believe I have become productive quickly using this application. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 9 | Whenever I make a mistake when using the application, I can recover easily and quickly. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 10 | It was easy to find the information that I needed. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 11 | The information provided by the application is easy to understand. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 12 | The information provided by the application helps me complete tasks. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 13 | The organization of the information on the application is clear. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 14 | I like using the interface of this application. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 15 | This application has all the features that I was expecting. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 16 | Overall, I am satisfied with this application. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

* 1—Strongly disagree; 2—Disagree; 3—Neither agree or disagree; 4—Agree; 5—Strongly agree.

References

- Staff. Worldwide Ecommerce Is on the Rise, Despite Retail Downturn. Available online: https://www.visionmonday.com/eyecare/coronavirus-briefing/the-latest-covid19-data/article/worldwide-ecommerce-is-on-the-rise-despite-retail-downturn/ (accessed on 25 January 2021).

- COVID-19: In-Store to E-Commerce Switch by Country 2020|Statista. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1105597/coronavirus-e-commerce-usage-frequency-change-by-country-worldwide/ (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- Sahin, A.; Zehir, C.; Kitapçı, H. The Effects of Brand Experiences, Trust and Satisfaction on Building Brand Loyalty: An Empirical Research on Global Brands. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 24, 1288–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bret on Social Games: My Coverage of Lobby of the Social Gaming Summit. Available online: http://web.archive.org/web/20220329172440/http://www.bretterrill.com/2008/06/my-coverage-of-lobby-of-social-gaming.html (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- Trends|Unity Blog. Available online: https://blog.unity.com/technology/2010-trends (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- FiveM—The GTA V Multiplayer Modification You Have Dreamt of. Available online: https://fivem.net/ (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- Cfx.re. Available online: https://github.com/citizenfx (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- Hamari, J.; Koivisto, J.; Sarsa, H. Does Gamification Work?—A Literature Review of Empirical Studies on Gamification. In Proceedings of the 47th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 6–9 January 2014; pp. 3025–3034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deterding, S.; Dixon, D.; Khaled, R.; Nacke, L. From Game Design Elements to Gamefulness: Defining “Gamification”. In Proceedings of the 15th International Academic MindTrek Conference: Envisioning future media environments, Tampere Finland, 28–30 September 2011; pp. 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Huotari, K.; Hamari, J. Defining gamification—A service marketing perspective. In Proceedings of the 16th International Academic MindTrek Conference, Tampere, Finland, 3–5 October 2012; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koivisto, J.; Hamari, J. The rise of motivational information systems: A review of gamification research. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 45, 191–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behl, A.; Sheorey, P.; Pal, A.; Veetil, A.K.V.; Singh, S.R. Gamification in E-Commerce. J. Electron. Commer. Organ. 2020, 18, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogg, B. Persuasive computers: Perspectives and Research Directions. In Proceedings of the CHI98: ACM Conference on Human Factors and Computing Systems, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 18–23 April 1998; ACM Press: New York, NY, USA; pp. 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karać, J.; Stabauer, M. Gamification in E-Commerce. In Proceedings of the International Conference on HCI in Business, Government, and Organizations, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 13 May 2017; pp. 41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Seaborn, K.; Fels, D.I. Gamification in theory and action: A survey. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2015, 74, 14–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamari, J. Why do people buy virtual goods? Attitude toward virtual good purchases versus game enjoyment. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2015, 35, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preist, C.; Massung, E.; Coyle, D. Competing or Aiming to Be Average?: Normification as a Means of Engaging Digital Volunteers. In Proceedings of the CSCW’14: Computer Supported Cooperative Work, Baltimore, MA, USA, 15–19 February 2014; pp. 1222–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Kim, S. Leaderboard Design Principles to Enhance Learning and Motivation in a Gamified Educational Environment: Development Study. JMIR Serious Games 2021, 9, e14746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yu, X.; Voida, S. Designing Leaderboards for Gamification: Perceived Differences Based on User Ranking, Application Domain, and Personality Traits. In Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Denver, CO, USA, 6–11 May 2017; pp. 1949–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartle, R. Hearts, Clubs, Diamonds, Spades: Players Who Suit Muds. J. MUD Res. 1996, 1, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Lagos, R.L.; Lopes, L.F.B.; Moreira, J. Bartle’s Test—Reinventing the Test. In Proceedings of the 13th International Technology, Education and Development Conference (INTED2019), Valencia, Spain, 11–13 March 2019; pp. 2433–2441. [Google Scholar]

- Charkova, D. University of Plovdiv “Paisii Hilendarski” Gamification in Language Teaching at the University Level: Learner Profiles and Attitudes. Chuzhdoezikovo Obuchenie-Foreign Lang. Teach. 2022, 49, 272–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gende, I.M.; Corces, M.G.; del Rio, A.C. Gamification within the English Classroom. In Proceedings of the 11th International Technology, Education and Development Conference (INTED2017), Valencia, Spain, 6–8 March 2017; pp. 733–741. [Google Scholar]

- Sienel, N.; Münster, P.; Zimmermann, G. Player-Type-based Personalization of Gamification in Fitness Apps. In Proceedings of the 14th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2021)—Volume 5: HEALTHINF, Online, 11–13 February 2021; pp. 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, M.J.P. The Medium of the Video Game; University of Texas Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konert, J.; Gutjahr, M.; Göbel, S.; Steinmetz, R. Modeling the Player: Predictability of the Models of Bartle and Kolb Based on NEO-FFI (Big5) and the Implications for Game Based Learning. Int. J. Game-Based Learn. 2014, 4, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariño, J.C.G.; Gallegos, M.L.C.; Cruz, H.E.C.; Camacho, J.A.R. Redesigning the Bartle Test of Gamer psychology for its application in gamification processes of learning. In Proceedings of the 12th International Multi-Conference on Society, Cybernetics and Informatics, Orlando, FL, USA, 8–11 July 2018; pp. 35–40. [Google Scholar]

- An Interview with Richard Bartle about Games & Gamification. Available online: https://www.gamedeveloper.com/design/an-interview-with-richard-bartle-about-games-gamification (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- Marczewski, A. Even Ninja Monkeys Like to Play: Gamification, Game Thinking and Moivational Design; CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform: Scotts Valley, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tondello, G.F.; Wehbe, R.R.; Diamond, L.; Busch, M.; Marczewski, A.; Nacke, L.E. The Gamification User Types Hexad Scale. In Proceedings of the 2016 Annual Symposium on Computer-Human Interaction in Play, Austin, TX, USA, 16–19 October 2016; ACM Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tondello, G.F.; Mora, A.; Marczewski, A.; Nacke, L.E. Empirical validation of the Gamification User Types Hexad scale in English and Spanish. Int. J. Human-Comput. Stud. 2019, 127, 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, Y.-K. Actionable Gamification: Beyond Points, Badges, and Leaderboards; Octalysis Media: Fremont, CA, USA, 2014; ISBN 1511744049. [Google Scholar]

- The Octalysis Framework—The Power of Behavioral Science behind Gamification—The Octalysis Group. Available online: https://octalysisgroup.com/the-octalysis-framework-the-power-of-behavioral-science-behind-gamification/ (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- Cassetti, L. A WORD FROM ECOMMERCE EUROPE. 2021. Available online: https://www.sgeconomia.gov.pt/noticias/european-e-commerce-report-2021.aspx (accessed on 27 February 2023).

- U.S. E-Commerce Share of Retail Sales 2021–2025|Statista. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/379112/e-commerce-share-of-retail-sales-in-us/ (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- Portugal: E-Commerce Share of Company Revenue 2020|Statista. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1017980/enterprises-e-commerce-share-total-turnover-portugal/ (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- International Trade Administration. Portugal—Country Commercial Guide. 23 January 2023. Available online: https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/portugal-ecommerce (accessed on 27 February 2023).

- Ecommerce Europe. European E-Commerce Report 2022. 2022. Available online: www.ecommerce-europe.eu (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- Sheetal; Tyagi, R.; Singh, G. Gamification and customer experience in online retail: A qualitative study focusing on ethical perspective. Asian J. Bus. Ethics 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedirko, O.; Zatonatska, T.; Wołowiec, T.; Skowron, S. Data Science and Marketing in E-Commerce Amid COVID-19 Pandemic. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2021, XXIV, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azmi, L.F.; Ahmad, N.; Iahad, N.A. Gamification Elements in E-commerce—A Review. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Congress of Advanced Technology and Engineering (ICOTEN), Taiz, Yemen, 4–5 July 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nah, F.F.-H.; Tan, C.-H. Gamification in E-Commerce A Survey Based on the Octalysis Framework. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference, HCIBGO 2017, Held as Part of HCI International 2017, PART II, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 9–14 July 2017; Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Costello, F.J.; Lee, K.C. The Unobserved Heterogeneneous Influence of Gamification and Novelty-Seeking Traits on Consumers’ Repurchase Intention in the Omnichannel Retailing. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morschheuser, B.; Hassan, L.; Werder, K.; Hamari, J. How to design gamification? A method for engineering gamified software. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2018, 95, 219–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, S. Design Thinking 101. 31 July 2016. Available online: https://www.nngroup.com/articles/design-thinking/ (accessed on 25 February 2023).

- Hartston, H. The Case for Compulsive Shopping as an Addiction. J. Psychoact. Drugs 2012, 44, 64–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figma. Available online: https://www.figma.com/login (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- Hamari, J.; Eranti, V. Framework for Designing and Evaluating Game Achievements. In Proceedings of the DiGRA’11: Proceedings of the 2011 DiGRA International Conference: Think, Design, Play, Utrecht School of the Arts, Hilversum, The Netherlands, 14–17 September 2011; The University of Tokyo: Tokyo, Japan, 2011, ISSN 2342-9666. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, J.R. IBM computer usability satisfaction questionnaires: Psychometric evaluation and instructions for use. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 1995, 7, 57–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J. Likert Scale. In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research; Michalos, A.C., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 3620–3621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevalier, S. «Global Retail Site Device Visit & Order Share 2022|Statista». 8 December 2022. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/568684/e-commerce-website-visitand-orders-by-device/ (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Statista Research Department. «eBay: Desktop and Mobile Site Traffic Share 202|Statista». 16 September 2022. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1333446/ebaywebsite-traffic-share-country/ (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Pedroso, T.; Cardoso, E.; Rações, F.; Baptista, A.; Barateiro, J. Learning Scorecard Gamification: Application of the MDA Framework. In Information Systems for Industry 4.0. Lecture Notes in Information Systems and Organisation; Ramos, I., Quaresma, R., Silva, P., Oliveira, T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meder, M.; Plumbaum, T.; Raczkowski, A.; Jain, B.; Albayrak, S. Gamification in E-commerce: Tangible vs. Intangible rewards. In Proceedings of the Academic Mindtrek 2018, Tampere, Finland, 10–11 October 2018; pp. 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzan, R.; DiMicco, J.M.; Millen, D.R.; Dugan, C.; Geyer, W.; Brownholtz, E.A. Results from deploying a participation incentive mechanism within the enterprise. In Proceedings of the CHI’08: CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Florence, Italy, 5–10 April 2008; pp. 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koivisto, J.; Hamari, J. Demographic differences in perceived benefits from gamification. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 35, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).