Abstract

This paper studies the problem of optimal reinsurance contract design. We let the insurer use dual utility, and the premium is an extended Wang’s premium principle. The novel contribution is that we allow for heterogeneity in the beliefs regarding the underlying probability distribution. We characterize layer-reinsurance as an optimal reinsurance contract. Moreover, we characterize layer-reinsurance as optimal contracts when the insurer faces costs of holding regulatory capital. We illustrate this in cases where both firms use the Value-at-Risk or the conditional Value-at-Risk.

1. Introduction

This paper studies the effect of different reference probability measures on reinsurance contracts. Due to asymmetric information, an insurer may use another probability measure than the reinsurer, that may price risk based on a population. Therefore, the price of reinsurance may seem very low for insurers that face relatively high risks. This observation forms the basis of adverse selection in insurance markets (Finkelstein and Poterba [1]). Alternatively, heterogeneity in reference probabilities may also be driven by ambiguity of the reinsurer (Hogarth and Kunreuther [2], Amarante et al. [3]).

In risk sharing, the aim is to redistribute risk among economical agents. For such problem, the effects of different reference probability measures is studied by Acciaio and Svindland [4] and Dana and Le Van [5]. Existence of Pareto optimal contracts is not guaranteed and both papers provide conditions for existence of Pareto optimal risk redistributions. Applications in redistributing longevity risk with heterogeneous reference probabilities are studied by Boonen et al. [6]. In this paper, we study an optimal reinsurance contract design problem, where mathematically the key difference with risk sharing is an ex post moral hazard constraint for the insurer (see, e.g., Huberman et al. [7]). This implies that the retained and ceded risk need to increase if the insured risk gets larger.

The reinsurance problem of this paper has a similar spirit as studied by Arrow [8]. He studies the case where one expected utility maximizing insurer is seeking for reinsurance. The reinsurance premium is hereby given by an expected value premium principle. This model is extended later by many authors. For instance, Young [9] studies the case where the premium is given by Wang’s premium principle. Moreover, Asimit et al. [10], Chi and Tan [11], Cui et al. [12], Assa [13], Balbás et al. [14], Cheung and Lo [15], Zhuang et al. [16]) all consider cases where the insurer minimizes a risk measure under a premium constraint.

Ghossoub [17] studies the problem where the insurer and reinsurer (or insurance buyer and insurer) have heterogeneous beliefs about the underlying probability distribution. To the best of our knowledge, this is the only study that considers heterogeneity in reference probability measures in a optimal (re)insurance contract design theory. We differ from Ghossoub [17] in two fundamental ways. First, we consider more general premium principles. We use generalized Wang’s premium principles, of which the expected value premium principle studied by Ghossoub [17] is a special case. Second, we focus on dual utility (Yaari [18]) as preferences of the insurer, whereas Ghossoub [17] uses expected utility. Our setting is in line with Cui et al. [12] and Assa [13], but extended to the case with heterogeneous reference probabilities.

Maximizing dual utility of future wealth is equivalent by minimizing a distortion risk measure (Wang et al. [19]) of future losses. Distortion risk measures include ambiguity by considering multiple scenarios, and then taking the worst-case. Alternatively, Balbás et al. [14] include ambiguity in reinsurance contract design. For special loss distributions, Huang et al. [20] show the equilibrium with asymmetric information. Ambiguity increases selection effects. Both papers use however a given reference probability measure that is the same for the insurer and the reinsurer.

As mathematical technique to solve the problems, we use the marginal indemnification function formulation as proposed by Assa [13] and Zhuang et al. [16]. By means of this technique, these authors solve a reinsurance problem with homogeneous reference probabilities as originally solved by Cui et al. [12]. Zhuang et al. [16] apply this technique to also solve a problem, where the insurer can only spend a maximum amount on reinsurance. In this paper, we propose this technique to solve a reinsurance problem with heterogeneous reference probabilities. Moreover, we show that this approach can be used in case the insurer also faces costs of holding risk capital. For homogeneous reference probabilities, this problem is studied by Cheung and Lo [15]. Our result extends the setting to allow for heterogeneous reference probabilities, and the proof is much simpler.

The remaining of this paper is constructed in the following way. Section 2 specifies the model. Section 3 shows our main result on optimal reinsurance contracts, and discusses the optimal contracts when there are costs of holding risk capital. Section 4 provides two examples; one with the Value-at-Risk and one with the conditional Value-at-Risk. Finally, Section 5 provides the conclusion and a concluding remark.

2. Model

Fix the state space Ω and σ-algebra Σ. We consider a one-period model with an insurer (I) and a reinsurer (R). The insurer faces a stochastic loss X that is measurable on Ω. The insurer seeks a reinsurance coverage against this loss with a reinsurer. We assume that the loss X has realizations on .

The insurer will cede the risk to the reinsurer, and pays a premium in return. It is common in the recent literature (e.g., Asimit et al. [10], Chi and Tan [11], Cui et al. [12], Assa [13]) to consider the following admissible set of ceded loss functions:

i.e., we assume that the indemnity is non-decreasing and 1-Lipschitz. Note that this set allows for deductible, or proportional reinsurance indemnities. The assumption that is often used in the literature on reinsurance contract design and its importance is particularly highlighted by Huberman et al. [7], Denuit and Vermandele [21], and Young [9]. Non-increasing reinsurance indemnities are perceived to be undesirable as it encourages the insurer to underreport its losses. On the other hand, if f were to increase more rapidly than losses increase, then the insurer would have an incentive to create incremental losses. Both of these cases trigger the so-called moral hazard in the sense that they create an opportunity for the insurer to misreport its actual losses to the reinsurer.

Note that every function is absolutely continuous, and thus, it is almost everywhere differentiable on , and there is a measurable function h such that

Here, is the slope of the ceded loss function f at z almost everywhere. Since , we can assume , where

To price risk, we make use of extended Wang’s premium principles. Such a premium principle is defined via risk measures. The risk measure depends on the countably additive probability measure on , that may vary in our subsequent definitions.

Definition 1.

A distortion risk measure of a random variable Z is defined as the following Choquet integral:

where at least one of the integrals in the right-hand side of (3) converges. Here, g is non-decreasing, and .

We define as the collection of non-decreasing functions satisfying and . For non-negative random variables Z, we note that (3) reduces to

Next, we define the premium principle that the reinsurer uses.

Definition 2.

The generalized Wang’s premium of a random variable Z is defined as

where and is a distortion function.

In the above definition, θ is the safety loading of the reinsurer. When , the distortion premium principle recovers the expected value premium principle. Furthermore, when the distortion function is concave and , the distortion principle recovers Wang’s premium principle (Wang [22]).

We also note the following properties of distortion risk measures :

- Comonotonic Additivity: for any two comonotonic random variables ;

- Translation Invariance: for any constant and random variable Z;

- Monotonicity: whenever -a.s.

The first property follows from Schmeidler [23], the second one follows from comonotonic additivity, and , and the last property is shown by Wang et al. [19].

3. Optimal Reinsurance Contract Design

In this section, we discuss the optimal reinsurance contracts. In Section 3.1, we discuss the baseline model, and in Section 3.2, we discuss the effects of holding a buffer.

3.1. Baseline Model

The insurer’s beliefs are represented by the countably additive probability measure on , and the reinsurer’s beliefs are represented by the countably additive probability measure on . Note that risk measures are meaningless whenever it is infinite. Therefore, we impose throughout this paper the following condition:

The wealth at a pre-determined future time for the insurer is given by

where is the initial wealth, , and . The insurer maximizes dual utility as introduced by Yaari [18], i.e., it maximizes

where is defined in (4). Let , , where is a distortion function. We do not require or to be concave 1.

We assume that the insurer maximizes its dual utility of terminal wealth. The insurer is allowed to buy any reinsurance indemnity , but needs to pay at least the premium given by the generalized Wang’s premium . This leads to the following optimal reinsurance problem:

Problem 1.

Theorem 1.

It holds that solves Problem 1 if and only if and f admits the following representation:

for all , - and -almost surely, where κ is a measurable and [0,1]-valued function on and is defined in Definition 2.

Proof.

Since the objective in Problem 1 satisfies translation invariance, it is strictly decreasing in π. Therefore, it holds that the premium constraint in Problem 1 must be binding: . Then, we get that the objective in Problem 1 writes as follows:

where we also use in the second equality that the distortion risk measure satisfies comonotonic additivity and the fact that and are comonotonic for all . Since we assumed , we get by monotonicity of that for all and all . So, (7) is finite.

Every function is absolutely continuous, non-decreasing, and such that . By standard rules of integration, we get that for every and set function v:

whenever the first integral is properly defined, where is a function coinciding almost everywhere with the derivative of f. Take for any measurable risk Y on Ω, and . Then, for every , there exists an independent of function , such that and for .

Maximizing (7) yields the same location of the optimum f as for the maximum of the following function:

Then, the result follows directly, and the proof is complete. ☐

Corollary 1.

Let solve Problem 1. If and , then whenever and whenever .

For instance, if , and , any contract with and solves Problem 1.

So, the optimal reinsurance contracts depend critically on , for Note that even if a firm assigns probability zero to an event, and the counterparty assigns a positive probability to this event, it may happen that the firm fully covers the risk in this event.

Remark 1.

Suppose we have multiple reinsurers that all use a generalized Wang premium principle as in Definition 2, but with heterogeneous parameters and reference probabilities. In case of homogeneous reference probabilities, Boonen et al. [24] show that minimizing the total premium for a given coverage yields a representative distortion premium principle for all reinsurers. With heterogeneous reference probabilities, this may no longer be the case. We here can use the same techniques as in Theorem 1 to solve an optimal reinsurance problem with multiple reinsurers. This also leads to optimality of layer-reinsurance.

3.2. Costs of Regulatory Capital

In this subsection, we study the case when the insurer bears costs of holding regulatory capital. The insurer is enforced hold risk capital given by , where , , is a distortion risk measure used to determine the risk capital is based on the probability measure . Such a valuation principle is used commonly in practice and is embedded in regulatory requirements under the Swiss Solvency Test and Solvency II (see, e.g., Chi [25], Asimit et al. [26], and Cheung and Lo [15]). The wealth at a pre-determined future time for the insurer is given by

where is the cost of capital as a percentage of the risk capital. Suppose the risk capital is determined by , where . We assume and .

Similar to Problem 1, we assume that the insurer maximizes its dual utility of future wealth, where the insurer is allowed to buy any reinsurance indemnity under a premium constraint. In this subsection, we however include costs of holding regulatory capital in the terminal wealth. This leads to the following problem:

Problem 2.

where is defined in Definition 2.

Lemma 1.

Contract is a solution of the Problem 2 if and only if it solves:

where

Proof.

We obtain

Here, the second equality follows from translation invariance, and the third equation is due to comonotonic additivity and the fact that and are comonotonic. Then, since and X are given, maximizing this yields the same location of the optimum as for the maximum of . This concludes the proof. ☐

Note that the function is not required to be non-decreasing. If it is non-decreasing, it is a distortion function. The following result provides the optimal reinsurance contracts of Problem 2.

Theorem 2.

It holds that solves Problem 2 if and only if and f admits the following representation:

for all , - and -almost surely, where κ is a measurable and [0,1]-valued function on . Here, is defined in (10).

Proof.

Since and , we have by monotonicity of distortion risk measures that for all .

Moreover, by (8), we have that for every , there exists an independent of function , such that and . Using this and Lemma 1, we get that the rest the proof of the theorem is similar to the proof of Theorem 1. ☐

So, even when risks are valued by means of non-monotonic preferences, we characterize optimal reinsurance contracts in Theorem 2. We find again that an optimal reinsurance contract is layer-reinsurance.

Suppose the risk capital is based on the beliefs instead of , where is a countable additive probability measure on . Then, the optimal reinsurance indemnity functions in Theorem 2 need to be adjusted in line with Theorem 1. Then, the constraints of the function in (11) are based on instead of for . So, we remain to have layer-reinsurance in optimal reinsurance contracts.

4. Two Examples

In this section, we illustrate Theorem 1 by means of two examples. The two most commonly used distortion risk measures in the literature are the Value-at-Risk (VaR) and the Conditional Value-at-Risk (CVaR), which we illustrate in Subsection 4.1 and Subsection 4.2. The reason for taking these two risk measures as the criteria for optimal reinsurance is due to their popularity among banks and insurance companies for quantifying risks and determining capital requirements. Asimit et al. [26] study our setting with VaR and CVaR in the context of insurance risk transfers in more detail in case of a homogeneous reference probability.

4.1. Value-at-Risk

A prominent example of distortion risk measures is the Value-at-Risk (VaR). For instance, it is used in Solvency II regulations. The VaR of a random variable Z at a confidence level is given by:

The VaR has distortion function for (see Dhaene et al. [27]).

The focus of this paper is on heterogeneity of reference probability, and so we assume that both firms use a different probability distribution of X. A popular, non-negative distribution with one parameter is the exponential distribution. An exponentially distributed variable X with parameter has survival function for . The insurer believes that the risk X is exponentially distributed with parameter , and the reinsurer believes that the risk X is exponentially distributed with parameter .

Since X is continuously distributed, we get the VaR by solving . We get

Suppose both the insurer and the reinsurer use VaR with parameters and respectively. From Theorem 1, we get immediately that the optimal marginal indemnity contract has the following functional form when :

for all , - and -almost surely. Moreover, when , we get

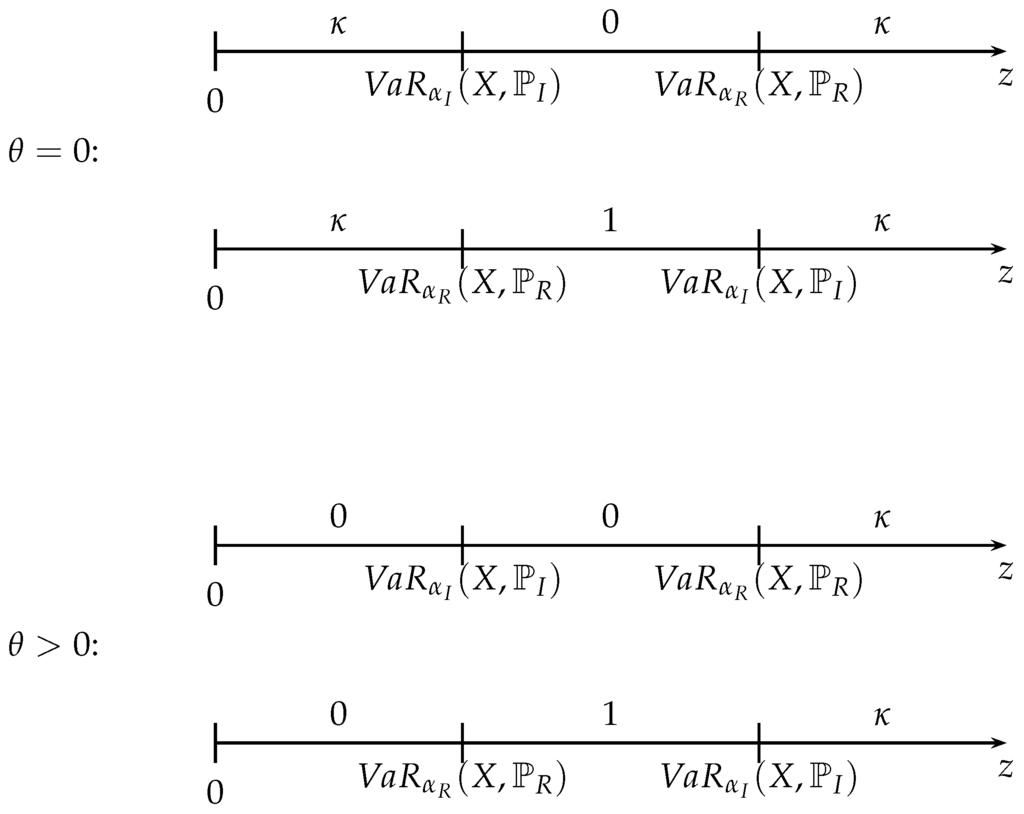

for all , - and -almost surely. So, the contracts critically depend on whether we have We illustrate the four different cases in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

This figure graphically illustrates the optimal marginal indemnity function of Theorem 1 in case the Value-at-Risk (VaR) is used. The range of X, denoted by , is partitioned in sub-domains, and the value is shown above the relevant sub-domain. Recall that , and is any measurable and [0,1]-valued function. The first two illustrations represent cases where , and in the last two illustrations represent cases where . Moreover, the first and third illustration show the case that , and the second and last illustration show the case that .

The derived optimal reinsurance indemnities include layer-reinsurance. Proportional reinsurance is however never optimal unless and both hold. In that case, every indemnity is optimal. If, for instance, we are at a realization z of X such that , then marginal increases in risk at z will be irrelevant for , but not for . As a result, it is optimal to shift marginal risk to the reinsurer, i.e., .

4.2. Conditional Value-at-Risk

Another prominent example of distortion risk measures in the conditional VaR. It is also known as expected shortfall, and it is used in the Swiss Solvency Test and the new Basel regulations. The conditional VaR of a random variable Z at a confidence level is given by:

provided that the integral exists. The distortion function of is given by for (see Dhaene et al. [27]).

When, according to , the risk X is exponentially distributed with parameter , we find

where the second step can be shown by L’Hôpital’s rule.

Suppose both the insurer and the reinsurer use the conditional Value-at-Risk (CVaR) with parameters and respectively. From Theorem 1, we get immediately that optimal reinsurance contracts have the following functional form:

for all , - and -almost surely. From (12), we can write this as follows

for all , - and -almost surely. This allows for many reinsurance contracts. If, for instance, we are at a realization z of X such that , then marginal increases in risk at z will be more sensitive for than for . As a result, it is optimal for the insurer to keep the marginal risk, i.e., .

In general, we find that the structure of the optimal indemnity functions contain more parameters compared to the case with VaR. If gets larger, then the insurer believes that the risk is larger in expectation, and so there is optimal reinsurance contract in which the insurer will reinsure more: weakly increases for all . Likewise, if the price gets smaller due to a smaller value of or , there is an optimal reinsurance contract in which the insurer will reinsure more.

5. Conclusions and Concluding Remark

In this paper, we characterize optimal reinsurance contracts under a moral hazard constraint. Our novel contribution is the focus on heterogeneous beliefs regarding the underlying probability distribution. We solve the optimal reinsurance problem by means of the marginal indemnification method approach, as introduced by Assa [13]. We find that optimal reinsurance indemnity functions are given by layer-reinsurance.

We study the case where an insurer seeks reinsurance with only one reinsurer. This setting seems restrictive, but can easily be extended to the case with multiple reinsurers. In that case, there is also optimality of layer-reinsurance, but different layers are possibly reinsured by different reinsurers.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- A. Finkelstein, and J. Poterba. “Adverse selection in insurance markets: Policyholder evidence from the UK annuity market.” J. Polit. Econ. 112 (2004): 183–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R.M. Hogarth, and H. Kunreuther. “Risk, ambiguity, and insurance.” J. Risk Uncertain. 2 (1989): 5–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Amarante, M. Ghossoub, and E. Phelps. “Ambiguity on the insurerances side: The demand for insurance.” J. Math. Econ. 58 (2015): 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B. Acciaio, and G. Svindland. “Optimal risk sharing with different reference probabilities.” Insur. Math. Econ. 44 (2009): 426–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R.A. Dana, and C. le van. “Overlapping sets of priors and the existence of efficient allocations and equilibria for risk measures.” Math. Financ. 20 (2010): 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T.J. Boonen, A. de Waegenaere, and H. Norde. Bargaining for Over-the-Counter Risk Redistributions: The Case of Longevity Risk. CentER Discussion Paper Series No. 2012-090; Tilburg, The Netherlands: Tilburg University, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- G. Huberman, D. Mayers, and C.W. Smith Jr. “Optimal insurance policy indemnity schedules.” Bell J. Econ. 14 (1983): 415–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K.J. Arrow. “Uncertainty and the welfare economics of medical care.” Am. Econ. Rev. 53 (1963): 941–973. [Google Scholar]

- V.R. Young. “Optimal insurance under Wang’s premium principle.” Insur. Math. Econ. 25 (1999): 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A.V. Asimit, A.M. Badescu, and K.C. Cheung. “Optimal reinsurance in the presence of counterparty default risk.” Insur. Math. Econ. 53 (2013): 690–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. Chi, and K.S. Tan. “Optimal reinsurance with general premium principles.” Insur. Math. Econ. 52 (2013): 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W. Cui, J. Yang, and L. Wu. “Optimal reinsurance minimizing the distortion risk measure under general reinsurance premium principles.” Insur. Math. Econ. 53 (2013): 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Assa. “On optimal reinsurance policy with distortion risk measures and premiums.” Insur. Math. Econ. 61 (2015): 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Balbás, B. Balbás, R. Balbás, and A. Heras. “Optimal reinsurance under risk and uncertainty.” Insur. Math. Econ. 60 (2015): 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K.C. Cheung, and A. Lo. “Characterizations of optimal reinsurance treaties: A cost-benefit approach.” Forthcoming in Scand. Actuar. J., 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S.C. Zhuang, C. Weng, K.S. Tan, and H. Assa. “Marginal indemnification function formulation for optimal reinsurance.” Insur. Math. Econ. 67 (2016): 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Ghossoub. “Arrow’s Theorem of the Deductible with Heterogeneous Beliefs.” Forthcoming in N. Am. Actuar. J., 2016. [Google Scholar]

- M.E. Yaari. “The dual theory of choice under risk.” Econometrica 55 (1987): 95–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S.S. Wang, V.R. Young, and H.H. Panjer. “Axiomatic characterization of insurance prices.” Insur. Math. Econ. 21 (1997): 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R.J. Huang, A. Snow, and L.Y. Tzeng. “Ambiguity and Asymmetric Information.” Available online: http://www.aria.org/meetings/2012%20Meetings/2C-Ambiguity%20and%20Asymmetric%20Information.pdf (accessed on 4 July 2016).

- M. Denuit, and C. Vermandele. “Optimal reinsurance and stop-loss order.” Insur. Math. Econ. 22 (1998): 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S.S. Wang. “Premium calculation by transforming the layer premium density.” ASTIN Bull. 26 (1996): 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. Schmeidler. “Integral Representation without Additivity.” Proc. Am. Math. Soc. 97 (1986): 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T.J. Boonen, K.S. Tan, and S.C. Zhuang. “The role of a representative reinsurer in optimal reinsurance.” Insur. Math. Econ., 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. Chi. “Reinsurance arrangements minimizing the risk-adjusted value of an insurer’s liability.” ASTIN Bull. 42 (2012): 529–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A.V. Asimit, A.M. Badescu, and A. Tsanakas. “Optimal risk transfers in insurance groups.” Eur. Actuar. J. 3 (2013): 159–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Dhaene, S. Vanduffel, M. Goovaerts, R. Kaas, Q. Tang, and D. Vyncke. “Risk measures and comonotonicity: A review.” Stoch. Models 22 (2006): 573–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 1.Concave distortion functions resemble aversion to mean-preserving spreads (Yaari [18]).

© 2016 by the author; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).