Abstract

This study examines the impacts of Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) systems on financing costs from the dual perspectives of risk management and relative value creation based on corporate value maximization objectives. Data were manually collected from the listed companies in China. It is found that the equity financing cost and debt financing cost of enterprises implementing ERP systems are both significantly higher than those without, and the impact of the ERP systems on equity financing cost is more significant than on debt financing cost. The endogeneity problems are addressed using the fixed effect, the instrumental variables in the two-stage least squares (2SLS) regression test, and the Heckman two-stage regression test. Further exploration into the underlying reasons for these results through mechanism analysis reveals that ERP systems can systematically and effectively enhance risk management levels and corporate value returns, bringing higher returns for investors and achieving a win-win situation. These research findings fundamentally help alleviate the agency problems between companies and investors, and also explain the advantages of an investment-oriented capital market in resolving conflicts among its various participants. Additionally, heterogeneity analysis further shows that the ownership structure and age structure of enterprises have a significantly negative moderating effect on the above results, and the moderating effect on equity financing cost is stronger than on debt financing cost.

1. Introduction

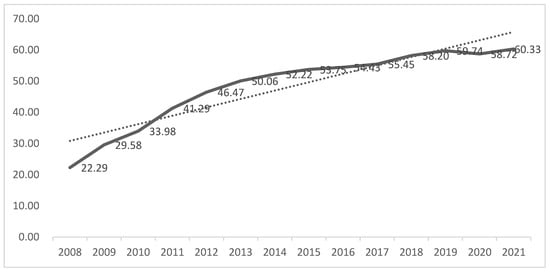

With the continuous advancement of information technology, ERP systems have become indispensable in the field of global business operations. By consolidating both internal and external data flows, ERP systems significantly improve enterprises’ operational efficiency, profitability, and capacity for value creation. In terms of operation, the implementation of an ERP system can effectively improve order delivery speed (Cotteleer and Bendoly 2006), logistics and support (Dehning et al. 2007), management forecasting quality (Dorantes et al. 2013), coordination ability and task efficiency (Gattiker and Goodhue 2005), and other business processes such as planning and control (Olson et al. 2013). In terms of profitability, ROA, ROE, and ROS (Hendricks et al. 2007) can be effectively increased; In terms of enterprise value, the market shows a positive response and return to the adoption of ERP systems (Ranganathan and Brown 2006). In recent years, there has been a notable increase in the adoption of ERP systems among listed companies in China. As illustrated in Figure 1, the percentage of these companies utilizing ERP systems rose from 22.29% in 2008 to 60.33% by 2021, reflecting a cumulative growth of over 38% across 14 years, with an average annual increase of approximately 2.7%. Accordingly, the government has introduced policy guidelines aimed at encouraging enterprises to undertake ERP implementation initiatives1.

Figure 1.

The proportion of listed companies implementing ERP systems (%). Source: Sample data of this study.

While the role of ERP systems in improving internal operational efficiency has been widely examined in existing studies, there is still a lack of systematic investigation into how ERP systems influence external financing costs, particularly in terms of equity and debt. ‘Difficult and costly financing’ has long been a major challenge for Chinese firms (Wang et al. 2022). However, whether this challenge is absolute depends largely on the perspective from which it is analyzed. Returns on capital can be viewed as two sides of the same coin, with different interpretations among stakeholders. From the firm’s viewpoint, it represents the cost of capital, whereas for investors, it reflects the returns on their investment. Essentially, financing issues are allocation issues. If the relationship between investors and companies is zero-sum, then companies will always face financing that is hard and expensive. However, if they have a mutually beneficial relationship, where both sides share common interests, then financing difficulty becomes a more relative issue. A key structural issue in China’s capital market is whether its functional orientation should emphasize financing or investment (Wu and Fang 2021). In the past, China’s capital markets mainly focused on financing, which often created a zero-sum relationship between investors and companies. This structure has weakened trust between the two sides and led to negative effects for the market (Allen et al. 2024), turning it into a place for speculation. Hence, enhancing the capital market’s investment function, rather than focusing solely on financing, is key to solving the problem of ‘Difficult and costly financing’.

However, ERP systems, functioning as comprehensive information management platforms, can help alleviate the core conflict between enterprises and investors by improving risk management capacity and enhancing corporate value. Driven by the aim of resolving this issue, this study thoroughly examines the distinct effects of ERP systems on equity and debt financing costs from the dual perspectives of risk management and relative value creation, under the objective of maximizing corporate value. This study intends to empirically examine the variations in financing costs following the adoption of ERP systems by Chinese enterprises and uncover the specific mechanisms through which ERP systems influence financing. This study extends Zhang et al. (2025), which focuses solely on equity financing, by further examining the impact of ERP implementation on debt financing costs and analyzing the similarities and differences in its effects on both financing methods, with the aim of providing a more comprehensive understanding of how ERP systems influence corporate financing decisions.

To implement our study, a panel of firm-state-year observations is constructed based on manually collecting the data from the annual reports of A-share listed companies on the Shenzhen Stock Exchange (SZSE) and the Shanghai Stock Exchange (SSE) from 2008 to 2021 through textual analysis. Ordinary least squares (OLS) and two-stage least squares (2SLS) are employed for baseline regression, as the implementation of ERP systems is a self-motivated and endogenous management behavior of enterprises in pursuit of corporate goals.

The endogeneity issues are addressed by using the fixed effects model, the two-stage least squares (2SLS) regression, and the Heckman two-stage regression. Given the characteristics of China’s industrial policies and their strong influence on financing pathways, the problem of omitted variable bias has been alleviated to some extent by adopting industry and time fixed effects. Employing the instrumental variable method to mitigate endogeneity issues arising from potential reverse causation. Using the Heckman two-stage model to detect and correct for self-selection bias issues. Finally, the results have found that the equity financing cost and debt financing cost of listed companies implementing ERP systems are both higher than those not implementing ERP systems, and the impact of the ERP systems on equity financing cost is more significant than its impact on debt financing cost. These results are consistent with the hypothesis, indicating that the application of ERP systems is in line with the goal of maximizing enterprise value.

Further exploration into the underlying reasons for these results through mechanism analysis reveals that ERP systems can systematically and effectively enhance risk management levels and corporate value returns, thereby bringing higher returns for investors and achieving a win-win situation. Our research results fundamentally help alleviate the agency problems between enterprises and investors, and also explain the advantages of an investment-oriented capital market in resolving conflicts among its various participants. Additionally, the results of the heterogeneity analysis further confirm the findings above and suggest that the growth and maturity stages are relatively optimal periods for enterprises to implement ERP systems.

The underlying reasons for these results are then explored through mechanism analysis. Assessing the impact of ERP systems implementation on equity financing cost and debt financing cost through two mediating dimensions: risk management level and relative value creation level (relative value refers to the consideration of the value of relevant stakeholders). Among them, risk management level is further divided into risk level and internal control level, and relative value creation level is subdivided into operational level and relative value level. Through an analysis of the impact paths of the above two dimensions, it becomes evident that ERP systems can effectively optimize and balance risks by strengthening internal control within the dimension of risk management, and can enhance enterprise value by improving operational efficiency within the dimension of relative value creation, which is ultimately reflected in increased financing costs or investor returns. That is, ERP systems are capable of systematically and efficiently improving enterprise risk management capability and corporate value creation level, thereby generating greater investor returns and realizing a mutually beneficial outcome. These mediation analysis results of different dimensions and levels further validate the hypothesis.

Finally, property nature (SOE) and company age (Age) serve as exogenous moderator variables to further structurally validate the research question. There are two important reasons: First, unlike foreign markets, China has a large number of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) participating in the market, especially holding a significant position in the capital market, but they are very different from private enterprises in terms of corporate objectives and financing constraints; Second, ERP systems implementation is a capital-heavy, long-term project, and with a high risk of failure throughout the implementation process, but enterprises in different stages have varying capacities to bear the risk. The heterogeneity test found two results. The first is that the implementation of ERP systems in SOEs will weaken their impact on equity and debt financing costs, and the moderating effect on equity financing cost is stronger than on debt financing cost; the second is that the implementation of ERP systems in long-established enterprises will weaken the impact of ERP systems implementation on equity financing cost and debt financing cost, and the moderating effect on equity financing costs is stronger than on debt financing costs.

Our research makes three main contributions. First, our research addresses the gap in archival studies regarding the impact of ERP systems on corporate financing costs. Although ERP systems have been widely studied in terms of implementation and performance improvement, few archival studies have explored their impact on corporate financing costs, particularly from the perspectives of risk management and value creation. Our study fills this gap by using a sample of Chinese enterprises to investigate this impact, expanding the theoretical scope of financing cost analysis and providing feedback to ERP system developers on whether their system design effectively enhances overall risk control and value creation for enterprises.

Second, our research outcomes play a fundamental role in mitigating agency problems between companies and investors. Specifically, it contributes to addressing the challenge of determining the functional orientation of capital markets in emerging economies or during times of economic transition. The core contradiction in such markets lies in whether the capital market should be oriented toward financing or investment (Wu and Fang 2021). Existing studies generally lean toward a financing-oriented perspective, mainly from the viewpoint of corporate finance departments, which often emphasize strict risk control to minimize financing costs for enterprises (Xu and Lv 2007). Nevertheless, this perspective weakens the trust relationship between investors and companies, resulting in negative effects on the capital market (Allen et al. 2024). Our study demonstrates that companies should prioritize an investment-oriented strategy, which can improve corporate value through overall risk management, ensure investors receive their rightful returns, promote mutual benefits, and help address the issue of ‘difficult and costly financing’.

Third, from a managerial perspective, these findings not only illuminate the reasons behind the sustained outperformance of low-risk stocks in China’s capital market but also reinforce the observed negative correlation between risk and return in major international capital markets. The capital market is an interdisciplinary field of finance and management, and the explanations of abnormal returns of low-risk stocks are given from the theoretical point of view in finance (Blitz et al. 2013). Our paper examines and explains the abnormal returns of low-risk stocks from the risk management perspective using more convincing accounting data based on the enterprise value objective. In an incomplete market, abnormal return on investment reflects the intrinsic value of enterprises, which should be consistent with the direction of enterprise operation results. This is consistent with our findings.

Fourth, it is found that the implementation of ERP systems in SOEs will weaken their impact on equity and debt financing costs, and this can enlighten us to think about the impact of corporate ownership on capital markets. It is also found that the decline period is not a good period for enterprises to implement ERP systems. In reality, it backfired for many enterprises to think of turning the tide through ERP deployment in the decline stage.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews the relevant literature and theories and proposes the hypotheses; Sample selection and research design are presented in Section 3; Section 4 reports and analyses the empirical results, including descriptive statistical analysis and basic regression analysis; The endogenous problem is addressed in Section 5; Section 6 and Section 7 provide further analysis, including mechanism analysis and heterogeneity analysis, respectively; and Section 8 concludes and discusses the results of this paper.

2. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypotheses

The financing decision of an enterprise is directly subject to the level of financing costs, which will further affect the overall operation level of the enterprise, and the operation level will, in turn, determine the level of financing costs, forming a closed loop. At the same time, for investors, the costs of financing are the return on investment required for the investment asset or project. Therefore, enterprises should weigh the advantages and disadvantages from a broader perspective, guided by strategic objectives and multi-stakeholder interests, rather than constrained departmental goals, when making financing decisions. (Berry-Stölzle and Xu 2018; Anton and Nucu 2020). However, when studying financing costs or return on investment, most existing literature usually does research based on models and theories related to the concept of risk premium, only from the perspective of financial departments and certain stakeholders. Studying the problem from a single theoretical framework cannot fully explain the complex reality of enterprise operation, which may lead to a deviation between the conclusion and the reality (Khan et al. 2016). Therefore, this study investigates the impact of ERP systems implementation on financing costs based on enterprise objective theory and risk management theory.

To avoid confusion and maintain the overall consistency of our research, three clarifications are provided: First, notable distinctions exist between equity financing and debt financing, as well as among different types of debt financing (e.g., bank loans and bond issuance). Although most existing studies tend to carry out segmented examinations and analyses based on such distinctions, this study incorporates both financing forms to improve generalizability (Mande et al. 2012). This is because our research emphasizes the influence of ERP systems on the shared features of equity financing and debt financing. This viewpoint strengthens the generalizability of our conclusions. Moreover, existing literature on the impact of ERP systems on financing costs is relatively scarce. Therefore, the analysis begins with the commonalities, laying the foundation for future research on specific financing forms. Second, “corporate risk” in this context specifically refers to “information risk.” However, this does not imply a conflation of the two terms. There are two main reasons for not explicitly distinguishing between them: (1) There is no standardized naming convention for risks, and different enterprises may classify and name risks according to their specific circumstances. Nevertheless, information risk is often considered the foundational layer of other risks. (2) Information risk management is a core function of ERP systems, and this article primarily examines the impact of ERP implementation on investor returns from the perspective of information risk management. Third, the terms “investment returns” and “financing costs” are interchangeable, with opposite subjects but equal values. Unless otherwise specified, the investment returns include equity investment return and debt investment return. Similarly, financing costs include equity financing costs and debt financing costs.

On the one hand, the impacts of ERP on financing costs are analyzed based on the risk-related CAPM and information asymmetry theory.

The determining factor of enterprise financing costs mainly lies in its risk level (Xu and Lv 2007), which has been verified in various pricing models. Risk premium is a core concept in pricing models, with models such as the capital asset pricing model, credit spread model, loan pricing model, and other pricing models treating it as a key factor. Therefore, stock financing cost, bond financing cost, bank loan interest rates, and other financing tools are closely related to risk premiums. The information asymmetry in the principal-agent relationship will significantly increase the risk and its premium, thereby increasing the financing costs of the enterprise. Compared with investors, enterprise managers have more and more accurate internal information about enterprises, which makes them have potential moral hazard. For investors, the adverse outcomes caused by such information asymmetry are perceived as risks, mainly from the uncertainty of the pre-transaction corporate situation and post-transaction corporate behavior (Lu et al. 2014). To address this uncertainty and unpredictability, investors will charge a risk premium for the uncertainty and thus improve the expected return on investment (Easley and O’Hara 2004), especially for bond investors, who are highly sensitive to default risks and promptly respond to risk signals (Wang and Zeng 2019).

Based on the enlightenment of the above models and theories, subsequent studies have explored ways to reduce the impact of information risk on investment returns by addressing information asymmetry from the perspective of information supply and information demand. In particular, the research on information disclosure and information acquisition is fruitful. Dhaliwal et al. (2011) think that information disclosure is one of the primary factors currently affecting financing costs. Numerous studies have been carried out mainly from different dimensions, such as the scope and quality of information disclosure and information acquisition costs. For instance, greater disclosure is associated with a lower cost of equity (Botosan 1997); increasing the disclosure of non-financial information can improve the information environment of the capital market, reduce the risk caused by investors’ cognitive bias, and then reduce the financing costs (Wang et al. 2014); the accuracy of information disclosure can reduce investors’ estimation deviation regarding future cash flow expectations between enterprises and other market participants, thereby lowering financing costs (Lambert et al. 2007); a policy of timely and detailed disclosures reduces lenders’ and underwriters’ perception of default risk for the disclosing firm, reducing its cost of debt (Sengupta 1998); information cost exacerbates information asymmetry between investors and enterprises, significantly limiting investors’ utilization of financial reporting information (Blankespoor et al. 2020). Lowering the cost for investors to acquire information can strengthen communication and interaction between principals and agents, helping to reduce the equity financing cost (Cai et al. 2022). In addition, there are also much literature from the perspective of the relationship between internal control and risk and finding that compared with enterprises without internal control deficiencies, enterprises with internal control deficiencies have higher idiosyncratic risks, systemic risks, and equity financing cost (Ashbaugh-Skaife et al. 2009; Khlif et al. 2019), higher debt financing cost (Kim et al. 2011), and more financing constraints (Kim et al. 2011; Gu and Jie 2018).

The implementation of ERP can reshape a company’s internal information environment, efficiently integrate information within and across functional departments (Yuan et al. 2017), enhance transparency (Al-Jabri and Roztocki 2015; Elsayed et al. 2019), and strengthen the company’s internal control systems (Zhang and Shou 2009), thereby influencing both the quantity and quality of information disclosed to the public (Dorantes et al. 2013). In addition, ERP implementation lowers the difficulty for auditors in accessing and reviewing corporate financial information (Morris and Laksmana 2010), shortens the time lag between fiscal year-end and earnings announcement (Brazel and Dang 2008), and facilitates the delivery of company and management information to investors (Yuan et al. 2017), indicating improvements in the timeliness of public information dissemination. Tian and Xu (2015) argue that ERP systems are capable of reducing firm risk. The Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO 2013) advocates for firms to use ERP systems to mitigate firm risk.

Based on these, this study proposes Hypothesis H1a.

H1a:

The financing costs of listed companies that implement ERP systems are lower, assuming other conditions remain unchanged.

On the other hand, the effects of ERP on financing costs are analyzed within the theoretical framework of risk management and enterprise value maximization strategic objectives.

According to the risk-related models and theories in hypothesis H1a, reducing corporate risk can reduce financing costs, which is theoretically established. However, this logic does not fully hold in practice. Enterprises need to achieve the optimal risk level and the best return through effective risk management according to their own conditions, rather than simply pursuing risk minimization. The pursuit of optimal capital structure is a classic study of optimal risk management. Related empirical studies also reveal the limitations of hypothesis H1a. For instance, Haugen and Heins (1972) first discovered the low-risk, high-return phenomenon in the U.S. capital market, and subsequent scholars further validated this conclusion using global data (Blitz et al. 2013; De Carvalho et al. 2012). This shows that it is difficult to fully explain the financing cost problem in reality by relying only on a single risk theory (Cai et al. 2022). Therefore, when analyzing financing costs, companies should not only base their analysis on risk theory but also align it with their strategic objectives, using scientific risk management to achieve the optimal balance between risk and return.

There are two aspects to be noted: The first is that the CAPM is founded on the efficient market hypothesis (EMH). In reality, different capital markets show significant variation in their effectiveness, and this phenomenon is common in the world. The second is that, according to Knight and existing theories (i.e., CFA Institute emphasizes the importance of considering unknown risks) on the definition of risk, absolute investment return (i.e., profit) in an incomplete market depends on “uncertainty” rather than “risk.” In Risk, Uncertainty and Profit (Knight 1921), he divided the current concept of risk into two parts: risk and uncertainty (For the convenience of understanding in the following text, risk = “risk” + “uncertainty,” i.e., the current concept of risk is not enclosed in quotation marks): the “Risk” is a measurable part that can be handled by human cognition, such as using the empirical laws of probability, while the “uncertainty” is an unknown and immeasurable part that cannot be determined by human cognition. This division can be considered as dividing risk into predictable risk and unpredictable risk. Therefore, assuming that “risk” is constant, high risk does not necessarily result in high investment return when the “uncertainty” part of certain investment assets or projects does not exist or approaches zero infinitely. Similarly, low risk does not necessarily result in low investment returns when the “risk” of certain investment assets or projects does not exist or approaches zero infinitely. In this case, investment returns should hinge on the structural composition of risk and the capacity to assess it, leading to varied outcomes. Enterprises aim to realize the optimal level of risk, maximize enterprise value, and obtain the best returns through effective risk management tailored to their specific conditions, rather than merely seeking risk minimization.

As an organization with multiple stakeholders, enterprises that simply focus on or pursue cost reduction may compress or harm the returns of other stakeholders, leading to a short-term “zero-sum” game, and making it difficult to achieve a long-term “win-win” situation. A sustainably developed enterprise should value growth as its core objective. This goal not only considers factors such as risk and time value but also highlights the economic claim rights of equity value and debt value (Xing 2009). Therefore, enterprises should fully consider the needs of stakeholders in risk management and avoid catering to the interests of specific groups.

The STRIVE financial management model2 proposed by Zhang and Hu (2016) follows a chain rule of “environmental analysis → corporate strategy → corporate goals → financial activities → response strategies,” emphasizing the promotion of corporate value growth through financial management activities directed by the enterprise’s strategic objectives while controlling various risks within the acceptable range of enterprises (Zhang et al. 2021). This model fully embodies the core role of financial management in coordinating corporate objectives and stakeholder needs. However, due to deficiencies in internal corporate governance, departments or individuals may exploit information asymmetry to pursue their own performance objectives in practical economic activities, which will undermine the achievement of the enterprise’s overall value objectives and infringe on the rights and interests of other stakeholders.

The ERP systems can effectively manage related risks. The organizational information processing theory (TOIP) suggests that, by enabling improved information processing and managerial decision making, IT systems, such as ERP systems, can help a firm better handle uncertainty (Tanriverdi and Ruefli 2004). Through real-time data analysis and risk monitoring, ERP systems assist in identifying and preventing potential risks. The integrated information platform enhances the transparency of information flow (Al-Jabri and Roztocki 2015; Elsayed et al. 2019) and improves communication efficiency, reducing information silos among departments (Gattiker and Goodhue 2005), promotes mutual supervision, and thereby reinforces the enterprise’s internal control mechanisms (Zhang and Shou 2009), which effectively mitigates moral hazards. In addition, ERP systems facilitate risk evaluation and optimization in strategic decision-making, allowing enterprises to better balance risk and return when implementing strategic plans (González-Rojas and Ochoa-Venegas 2017), thus supporting the realization of overall goals, enhancing corporate value, and increasing stakeholder returns.

Based on these, this study proposes the alternative Hypothesis H1b.

H1b:

The financing costs of listed companies that implement ERP systems are higher, assuming other conditions remain unchanged.

3. Sample Selection and Research Design

3.1. Sample Selection and Data Sources

This study selects China’s A-share listed companies from 2008 to 2021 as the research sample. Financial data and corporate governance data are mainly from the CSMAR database, partly from manual collection and collation (variable ERP, Supplier), RESSET database (variable Stdret), CNRDS database (variable SOE), Choice database (variable SOE), CCER database (variable SOE), DIB database (variable Control), as well as China Market Index Database (variable Market), which ERP data is obtained from the annual reports of A-share listed companies on the Shenzhen Stock Exchange (SZSE) and the Shanghai Stock Exchange (SSE) from 2008 to 2021 by textual analyses. Then, the data is processed and cleaned as follows: (1) Eliminating merged duplicates and entries duplicated due to transfer to the main board; (2) Deleting listed financial enterprises such as banks, insurance, and securities; (3) Removing ST and *ST listed enterprises; (4) Excluding enterprises with missing data and outliers in the variables. Ultimately, 3635 companies and 23,228 firm-year observations are retained. In order to eliminate the influence of extreme values, 1% winsorize is applied to both ends of continuous variables. The software used for data analysis in this paper is Stata 16 and Python 3.9.13.

While our study is similar to existing studies in terms of how to obtain data on ERP usage (Dorantes et al. 2013; Morris 2011; Cao et al. 2022), there are still two concerns about the sample and data that need to be clarified. One primary concern is that Chinese listed companies exhibit wide variability in quality, with many having yet to implement ERP systems systematically, which excludes companies that have sporadically adopted certain systems. ERP implementation here refers specifically to systematic implementation, which refers to cases where the ERP system constitutes a significant part of the company’s major investments.

The other primary concern is that since companies in China voluntarily disclose their ERP usage, ERP users may not fully disclose their past and current usage in corporate annual reports. However, we argue that not disclosing ERP usage is unlikely in China for three reasons. Firstly, ERP usage is an important investment that will take multiple years to implement, and the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) requires companies to disclose important investment decisions in a timely manner, whether financial or strategic. Secondly, ERP is a crucial tool for enterprise-wide risk management, and its investment in China is considered a strategic investment that provides competitive advantages (Blanco-Mesa et al. 2019), also indirectly illustrating one of the primary concerns mentioned above: many listed companies have not implemented ERP systems. Many companies use ERP implementation as a promotional tool to demonstrate their financial strength and internal control capacity. This way enhances shareholder confidence in the companies with ERP systems in China’s short-term financing-oriented capital market, which gives listed companies strong incentives to report ERP system implementation (Newman and Zhao 2008). Thirdly, the Chinese government encourages and promotes companies’ usage of information technology. When companies do something encouraged by the government, they are willing to report it because companies can leverage this as a bargaining chip to seek benefits related to the project from the government. This relationship between the government and businesses is a common phenomenon in China. Consequently, it is concluded that the potential disclosure selectivity is unlikely to be material enough to bias the inference of our tests.

3.2. Variable Selection and Definition

3.2.1. Explained Variables

Equity Financing Cost (r_PEG), currently, there are two main approaches to measure the cost of equity financing: ex-post equity cost measurement represented by the CAPM and the Fama-French three-factor model (Mazouz et al. 2014) (Although the CAPM was originally developed as an ex-ante model, it is often applied using historical data in academic research for non-predictive purposes, which is why it is referred to here as an ex-post model), and ex-ante equity cost measurement represented by models such as the PEG model (Easton 2004) and the GLS model (Gebhardt et al. 2001). In addition, ex-ante equity cost models also include the Gordon model (Gordon and Gordon 1997), MPEG model (Easton 2004), AGR model (Easton 2004), OJ model (Ohlson and Juettner-Nauroth 2005). Many scholars have pointed out the differences between the characteristics of ex-ante and ex-post equity cost models. They argue that ex-post equity cost models typically have more assumptions, are more incorrect, and have narrower applications (Fama and French 1997; Claus and Thomas 2001). Comparatively, the ex-ante equity cost models have fewer assumptions, more accurate and reliable estimation results, and broader applications. Particularly, the PEG model more effectively captures the effects of various risk factors and demonstrates greater applicability to the Chinese capital market compared to the above models. Therefore, the PEG model is used to estimate the cost of corporate equity financing. The specific formula for calculating the indicator is detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Variable definition.

Debt Financing Cost (r_DEBT), this article adopts the conventional treatment method to define the cost of debt financing, referring to references (Xu and Li 2020; Sun et al. 2022), and the specific formula for the calculation of the indicator is detailed in Table 1.

3.2.2. Explanatory Variables

ERP Implementation (ERP), Huang et al. (2020) constructed the measure of business and financial information integration (BFII) based on the management discussion and analysis (MD & A) in the annual report. However, due to the weak standardization of early reports by certain listed companies, this study, while referencing the aforementioned methods, extends the text scope from MD&A to the entire report to construct the ERP proxy variable and prevent the omission of some samples. The specific text analysis method for constructing ERP proxy variables follows the following six steps: First step, download the annual reports of all A-share listed companies on the SSE and SZSE for the first disclosure, taking into account that their information transmission effect in the capital market is stronger than the revised report. The second step is to convert all annual report formats into a unified text format. The third step is to use text analysis methods to extract keywords from all texts. In terms of the principle of word extraction, the methods are learned from Yuan et al. (2017). The keywords are set as “ERP” to more accurately distinguish ERP from other easily confusing concepts, such as digitalization or FBII. The fourth step is to sort out the companies that have implemented ERP manually. The fifth step is to use the same method above to process MD&A texts in the CSMAR database and compare the differences between the two results, manually checking and filling in the missing information. The sixth step is to set the ERP proxy variable. Considering that ERP systems are significant capital investment projects that are time-consuming and require substantial financial resources, if a company implements ERP in the observed year, then the variable ERP of the observation year and the following years is set to 1. Otherwise, it is 0.

3.2.3. Control Variables

In selecting control variables, this paper references and draws from a lot of literature. Due to the differing factors influencing equity financing cost and debt financing cost, this paper divides control variables into two groups according to the explained variables: control variables of equity financing cost and control variables of debt financing cost. This paper’s basic regression, mediation, moderation, and instrumental variable tests will all adhere to the abovementioned grouping.

Control Variables of Equity Financing Cost (Controls1), referring to relevant studies (Zhao et al. 2020; Wang and Tan 2022), the following control variables are set: company size (Size), asset-liability ratio (Lev), enterprise growth (Growth), return on assets (ROA), property nature (SOE), company age (Age), beta coefficient (Beta), market-to-book ratio (MB), interest coverage ratio (Interest), largest shareholder’s shareholding ratio (Top1), ownership and management right structure (Dual), proportion of independent directors (Independent), board size (Board), audit quality (Big4), analyst coverage (Analyst), marketization process degree (Market), tobin’s Q (Tobinq), cash dividend payout ratio (Dividend), Ind and Year refer to the industry and year, respectively, which are included as control variables to control the fixed effect of industry and year. The specific formula for calculating the indicators is shown in Table 1.

Control Variables of Debt Financing Cost (Controls2), drawing from relevant references (Xu and Li 2020; Sun et al. 2022), the following control variables are set: company size (Size), asset-liability ratio (Lev), enterprise growth (Growth), return on assets (ROA), operating cash flow (FCF), tangibility of assets (Tang), property nature (SOE), company age (Age), interest coverage ratio (Interest), proportion of independent directors (Independent), board size (Board), audit quality (Big4), analyst coverage (Analyst), net profit (Loss), marketization process degree (Market). Ind and Year refer to the industry and year, respectively, which are included as control variables to control for the fixed effect of industry and year. The specific formula for calculating the indicators is shown in Table 1.

3.3. Model Design

This research constructs models (1) and (2) to examine the impact of ERP implementation on equity financing cost and debt financing cost.

r_PEGi,t = α0 + α1ERPi,t + ∑Controls1i,t + ∑Indj + ∑Yeart + εi,t

r_DEBTi,t = β0 + β1ERPi,t + ∑Controls2i,t + ∑Indj + ∑Yeart + εi,t

Among them, r_PEGi, t is the proxy variable of equity financing cost, r_DEBTi, t is the proxy variable of debt financing cost, Controls1i, t and Controls2i, t are the control variables of equity financing cost and debt financing cost, respectively, and the specific definitions are shown in Table 1. If coefficient α1 is significantly less than 0, it indicates a negative correlation between the implementation of ERP and equity financing cost, suggesting that the implementation of ERP systems significantly reduces equity financing costs, thus supporting H1a. Conversely, if coefficient α1 is significantly greater than 0, it indicates a positive correlation between the implementation of ERP and equity financing cost, implying that the implementation of ERP systems significantly increases equity financing cost, thereby supporting H1b. If coefficient β1 is significantly less than 0, it indicates a negative correlation between the implementation of ERP and debt financing cost, suggesting that the implementation of ERP systems significantly reduces debt financing cost, thus supporting H1a. Conversely, if coefficient β1 is significantly greater than 0, it indicates a positive correlation between the implementation of ERP and debt financing cost, implying that the implementation of ERP systems significantly increases debt financing cost, thereby supporting H1b. Additionally, in order to alleviate the influence of heteroscedasticity on the regression results, heteroscedasticity-robust standard errors are uniformly employed in the basic regression, mediation regression, moderation regression, and instrumental variable regression.

4. Empirical Test and Result Analysis

4.1. Descriptive Statistical Analysis

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics of the main variables. First, the mean values of the variable ERP in the equity financing cost sample and the debt financing cost sample are 0.5389 and 0.5408, respectively, indicating that during the observation period of the sample, approximately 53.89% and 54.08% of the listed companies implemented ERP systems, providing a solid data foundation for this study. Second, the mean value of the variable r_PEG is 0.1072, with a standard deviation of 0.0412, while the mean value of the variable r_DEBT is 0.0191, with a standard deviation of 0.0146. According to the results, it is found that, on average, the difference between equity financing cost among different listed companies is significantly greater than the difference between debt financing cost among different listed companies. Finally, comparing the statistical results of p25, p50, and p75 quantiles of the entire sample, it can be observed that the equity financing cost and debt financing cost of listed companies that implemented ERP systems are significantly higher than those of listed companies that did not implement ERP systems.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistical analysis.

Table 3 reports the results of the correlation analysis. The Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients between the variable r_PEG and the variable ERP are 0.017 and 0.038, respectively, both significantly positively correlated at the 1% level. However, the Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients between the variable r_DEBT and the variable ERP are −0.097 and −0.078, respectively, both significantly negatively correlated at the 1% level. These data analysis results, to some extent, reflect that the cost of equity financing for listed companies implementing ERP systems is significantly higher than those not implementing ERP systems, while the cost of debt financing for listed companies implementing ERP systems is significantly lower than those not implementing ERP systems. Additionally, there are significant correlations between the variables r_PEG, r_DEBT, and other control variables. Although the correlation between each control variable is also significant, the coefficients are generally small, and their absolute values are generally between 0 and 0.3, with only a few exceeding this range. Therefore, the model is unlikely to have severe multicollinearity problems (further VIF testing will be conducted in subsequent analysis).

Table 3.

Key variable correlation coefficient matrix.

Table 4 reports the results of the univariate tests. For the sample group without implementing ERP systems, the mean of variable r_PEG is 0.106, with a median of 0.101. For the sample group implementing ERP systems, the mean of variable r_PEG is 0.108, with a median of 0.104. Therefore, on average, the cost of equity financing for listed companies implementing ERP systems is significantly higher than those not implementing ERP systems. Similarly, for the sample group implementing ERP systems, the mean of variable r_DEBT is 0.021, with a median of 0.019. For the ERP implementation group, the mean of variable r_DEBT is 0.018, with a median of 0.016. On average, the cost of debt financing for listed companies implementing ERP systems is significantly lower than those not implementing ERP systems.

Table 4.

Univariate test results.

In summary, the correlation analysis and univariate tests yielded relatively consistent results, indicating that the equity financing cost of listed companies adopting ERP systems is significantly higher than that of those not adopting ERP systems, while the debt financing cost of these companies adopting ERP systems is significantly lower than that of those not adopting ERP systems. However, the descriptive statistical results showed partially inconsistent findings, suggesting that listed companies implementing ERP systems exhibit higher costs in both equity and debt financing compared to those not implementing ERP systems. Therefore, further data examination and analysis are needed.

4.2. Baseline Regression (OLS Regression) Analysis

Table 5 presents the regression outcomes of ERP implementation on equity and debt financing costs. Column (1) shows that the coefficient of the variable ERP is significantly positive at the 1% level, after controlling for industry and year fixed effects as well as other control variables. Column (2) shows that the coefficient of the variable ERP is significantly negative at the 1% level under the same controls. The above results suggest that the equity financing cost of listed companies adopting ERP systems is higher than that of those not adopting ERP systems, supporting hypothesis H1b, while the debt financing cost of those companies adopting ERP systems is lower than that of those not adopting ERP systems, supporting hypothesis H1a. Specifically, the coefficient of the variable ERP in column (1) is 0.0016, indicating that, with control variables held constant, on average, the equity financing cost of listed companies implementing ERP systems is, on average, 0.16% higher than that of those not implementing ERP systems. Similarly, the coefficient of the variable ERP in column (2) is −0.0009, indicating that, with control variables held constant, the debt financing cost of listed companies implementing ERP systems is, on average, 0.09% lower than that of those not implementing ERP systems. In addition, multicollinearity tests were conducted on the two models, with the variance inflation factor (VIF) values basically within the [0, 3] range; although a few exceeded this interval, they remained far below the generally accepted threshold of 10. Therefore, the likelihood of multicollinearity in the models is minimal.

Table 5.

ERP implementation and equity and debt financing costs: baseline regression.

5. Robustness Tests

5.1. Endogeneity Issue Resolution

5.1.1. Instrumental Variable (IV) Method

Although the problem of omitted variable bias has been alleviated to some extent by improving control variables and adopting industry and time fixed effects, there is still a potential reverse causal relationship that influences the research results. Therefore, the instrumental variable method is further employed to alleviate endogeneity problems. This study employed a two-stage least squares regression (2SLS or TSLS) model with two instrumental variables: (1) the natural logarithm of the number of ERP providers within a 200 km radius of the registered location of listed companies (Supplier), and (2) the proportion of the accumulated number of other listed companies that have adopted ERP systems in the same province to the total number of listed companies in that province (Emulation).

Based on the fact that listed companies are more likely to receive attention from ERP suppliers and are more willing to choose ERP suppliers with convenient technical support and after-sales service, the geographical density of ERP suppliers will increase the opportunities for nearby listed companies to implement ERP (Cao et al. 2022). However, there is no direct causal relationship between the number of ERP suppliers within a radius of 200 km around the registered address of the listed company and the costs of equity financing and debt financing. Therefore, the variable Supplier theoretically satisfies the conditions of correlation and exogeneity of instrumental variables. The study involves four steps to calculate the number of ERP manufacturers or vendors within a radius of 200 km from the registered address of a listed company. First, download the latitude and longitude of all registered addresses of listed companies from the CSMAR database. Then, the registered geographical locations of major ERP manufacturers or suppliers in the Chinese Mainland (UFIDA, Kingdee, Inspur, Digiwin, SAP, Oracle, Accenture, IBM, Infor, and Sage) were manually collected through the Tianyancha official website, and they were converted into longitude and latitude using the Gaode Map API. After that, calculate the distance between the two locations based on the longitude and latitude of the registered address of the listed company and the registered address of the ERP manufacturer or supplier. Finally, the number of ERP suppliers within a radius of 200 km of the registered address of all listed companies was calculated based on the distance between the two locations.

DiMaggio and Powell (1983) believe that in order to enhance competitiveness, corporate management tends to emulate the experiences and practices they perceive as successful in dealing with uncertainty. Since implementing ERP systems can enhance a firm’s strategic competitive advantage, the more listed companies within a province implement ERP systems, the greater the likelihood of other companies within that province also adopting ERP systems (Yuan et al. 2017). However, there is no direct causal relationship between the number of ERP vendors within a 200 km radius around the listed company’s registered address and the costs of equity financing and debt financing. Therefore, the variable Emulation also theoretically satisfies the conditions of correlation and exogeneity for instrumental variables.

First, the two instrumental variables are regressed with the control variables in models (1) and (2), respectively, to obtain the fitted values of the core explanatory variable PERP; then, the fitted values of PERP are added to models (1) and (2) for regression, respectively. The final 2SLS results are shown in Table 6. In the first stage, the minimum eigenvalue statistic(F-value) of the weak instrument test results for models (1) and (2) are all greater than the critical value of 19.93 (Stock and Yogo 2002), which allows the acceptance of the test bias for weak instrumental variables to be 10% (not reported due to space limitations), and both are all greater than the empirical value 10, indicating that neither of the instrumental variables are weak instrumental variables. In the second stage, the sargan (score) chi2 (1) (p value) of the overidentification test (Sargan Test) results of models (1) and (2) are greater than 0.05, indicating that the instrumental variables meet the exclusivity requirements, and the durbin (score) chi2 (1) (p value) of the endogeneity test (Durbin-Wu-Hausman Test) results of models (1) and (2) are less than 0.05, indicating that the two models exist endogeneity. The above test results show that variable Supplier and variable Emulation are effective instrumental variables. Column (2) shows that the regression coefficient of the variable ERP is significantly positive at the 1% level, indicating that, all else being equal, on average, the cost of equity financing for listed companies implementing ERP systems is higher compared to those that do not implement ERP systems. Column (4) shows that the coefficient of the variable ERP is significantly positive at the 10% level, indicating that, all else being equal, on average, the cost of debt financing for listed companies implementing ERP systems is higher compared to those that do not implement ERP systems. It is noteworthy that this result contradicts the direction of the regression coefficient in the baseline regression results of Model (2).

Table 6.

Results of two-stage regression of instrumental variables.

5.1.2. Heckman Two-Stage Selection Model

ERP system implementation is an autonomous and endogenous managerial action taken by the enterprise. Consequently, the baseline model results may be subject to self-selection bias. This study employs the Heckman two-stage model to detect and correct for this bias. In the first stage, the probit models are constructed, and the inverse Mills ratios (IMRs) are computed. This process requires analyzing the factors influencing companies’ implementation of ERP systems. Following the approach of relevant literature (Anderson et al. 2006; Kobelsky et al. 2008; Dorantes et al. 2013; Tian and Xu 2015; Yuan et al. 2017), variables such as company size (Size), asset-liability ratio (Lev), enterprise growth (Growth), return on assets (ROA), equity nature (SOE), proportion of shares held by the largest shareholder (Top1), stock volatility (Stdret), and cash flow ratio (FCF) are included as control variables in the Probit model, with industry and time fixed effects controlled. Moreover, this study incorporates the instrumental variables, supplier and emulation, as exogenous variables in the model. In the second stage, the IMR is included as a control variable in the baseline models (1) and (2) for regression.

The regression results are presented in Table 7. The IMRs are both significantly negative; keeping the control variable constant, other unobserved factors can be predicted to have negative effects on the cost of equity capital and the cost of debt capital. In Column (2), the coefficient of the variable ERP is statistically significant at the 1% level, indicating that after controlling for industry and year fixed effects as well as other control variables, on average, listed companies adopting ERP systems exhibit a higher cost of equity financing compared to those not adopting ERP systems. In Column (4), the coefficient of the variable ERP is statistically significant at the 10% level, suggesting that, under the same control conditions, on average, listed companies adopting ERP systems exhibit a higher cost of debt financing compared to those not adopting ERP systems. It should be noted that this result is contrary to the direction of the regression coefficients in the baseline regression results of Model (2).

Table 7.

The results of Heckman two-stage regression.

Based on economic theory and the support from the above econometric results (the results of the instrumental variable method and Heckman two-stage model tests), the baseline regression (OLS) results are likely to suffer from significant endogeneity, rendering them biased and ineffective in explaining and predicting the economic phenomena and issues addressed in this paper. However, the instrumental variable method not only effectively mitigates the endogeneity problem caused by reverse causality but also reduces the bias arising from other sources of endogeneity. Accordingly, following the approach of Alesina and Zhuravskaya (2011), this study employs the 2SLS regression for both the baseline estimation and subsequent mechanism analysis (Nakamura et al. 2022). Finally, the results have found that the equity financing cost and debt financing cost of listed companies implementing ERP systems are both higher than those not implementing ERP systems, and the impact of the ERP systems on equity financing cost is more significant than its impact on debt financing cost.

5.2. Alternative Measurement of the Key Variable

The proxy for debt financing used in the baseline regression is scaled by total liabilities, reflecting a mix of internal and external financing. To better focus on capital market investors’ perspectives, an alternative proxy for external debt financing, such as bond yield spreads, is employed. The regression results using this alternative proxy are consistent with those obtained previously. In addition, ex-ante equity cost models, including the MPEG model (Easton 2004) and the OJ model (Ohlson and Juettner-Nauroth 2005), are also employed as alternative measures, and these results are consistent with the findings above.

6. Mechanism Analysis

Before investors make investments, they typically assess whether a listed company has investment value by paying attention to and analyzing various indicators, including financial and non-financial indicators. The implementation of ERP represents a significant strategic and capital investment for listed companies, and its impact involves all aspects of enterprise operation, which will be reflected in the financial and non-financial indicators of listed companies and ultimately transmitted to the capital market through various information channels and media, thereby influencing investors’ investment behavior and returns. Therefore, the variable ERP is the “macro variable” at the micro level. In view of its extensive influence, this study examines its influencing factors from multiple dimensions and indicators. Specifically, it assesses the influence of ERP systems implementation on equity and debt financing costs via two intermediary dimensions: relative value creation level and risk management level. The relative value creation level is further divided into relative value level and operational level, proxied by price-to-book ratio (BP) and working capital turnover (Turnover), respectively; the risk management level is subdivided into internal control level and risk level, proxied by internal control index (Control) and return volatility (Stdret), respectively. The selection of the mediation effects models (3), (4), and (5) is based on the method proposed by Wen et al. (2004). In addition, in order to suppress the endogeneity problem derived from the second stage, the approach of Jiang (2022) is employed to further validate the results of the mediation tests with existing relevant literature. Additionally, for space considerations, the mediator variables in the models are uniformly represented as “Mediator.” Table 8 presents the empirical results of all the mediation tests.

r_PEGi,t/r_DEBTi,t = γ0 + γ1ERPi,t + ∑Controlsi,t + ∑Indj + ∑Yeart + εi,t

Mediatori,t = γ0 + γ1ERPi,t + ∑Controlsi,t + ∑Indj + ∑Yeart + εi,t

r_PEGi,t/r_DEBTi,t = γ0 + γ1ERPi,t + γ2Mediatori,t + ∑Controlsi,t + ∑Indj + ∑Yeart + εi,t

Table 8.

ERP implementation on equity financing cost and debt financing cost: mediation effect.

6.1. Risk Management Level

6.1.1. Risk Level

The implementation of ERP systems can effectively reduce enterprises’ risks (COSO 2013; Tian and Xu 2015). For example, it can reduce order delivery risk and decrease resource redundancy risk. Enterprises with lower risk tend toward lower financing costs (Ashbaugh-Skaife et al. 2009; Kim et al. 2011; Khlif et al. 2019). As shown in Panel A, column (2), the coefficient of the variable ERP is negative and statistically significant at the 10% level, suggesting that the risk of listed companies adopting ERP systems is lower. Column (3) shows that the coefficient of the variable Stdret is significantly negative at the 1% level, indicating a significant negative correlation between risk and equity financing cost (Haugen and Heins 1975; Baker and Haugen 2012; Russo 2016). The coefficients of the variable ERP in columns (1) and (3) are 0.0279 and 0.0271, respectively, both significant at the 1% level. These experimental results suggest that the equity financing cost of listed companies adopting ERP systems is higher. In Panel B, column (3) shows that the coefficient of the variable Stdret is significantly positive at the 1% level, indicating a significant positive correlation between risk and equity financing cost, which is opposite to the results in Panel A. The direction of the mediation effect is opposite to the direction of the direct effect here, indicating there is a masking effect (MacKinnon 2008; MacKinnon et al. 2000, 2002; Shrout and Bolger 2002), which reason is that debt investors are more risk-averse than equity investors, preferring risk returns, while equity investors prefer relative value returns, which is ultimately reflected in the increase in debt financing cost. However, the final empirical results displayed in Panel B are consistent with those in Panel A, also showing an overall increasing trend in debt financing cost, indicating that the relative value orientation is still dominant. Therefore, the risk management level exerts a partial mediating effect on the impact of ERP systems adoption on the equity financing cost and debt financing cost.

6.1.2. Internal Control Level

Companies adopting ERP systems exhibit higher internal control quality (Chang et al. 2014; Morris 2011; Yuan et al. 2017), and enterprises with better internal control quality face fewer financing constraints (Gu and Jie 2018) and lower financing costs (Ashbaugh-Skaife et al. 2009; Kim et al. 2011; Khlif et al. 2019). It should be noted that there exists a strong interplay between risk management and internal control, which may result in a chain mediation effect, whereby enhanced internal control quality lowers enterprise risk and subsequently reduces financing costs. In Panel A, column (5) shows that the coefficient of the variable ERP is significantly positive at the 5% level, indicating that listed companies implementing ERP systems have higher internal control quality. Column (6) shows that the coefficient of the variable Control is significantly negative at the 5% level, indicating that with the improvement of internal control quality, the equity financing cost of listed companies will decrease correspondingly, demonstrating a masking effect, which because the increase in internal control quality not only reduces risk but also enhances the relative value of the enterprise (Wang et al. 2015). When the influence of value is weaker than the influence of risk, the result is a reduction in equity financing cost. The coefficients of the variable ERP in columns (5) and (6) are 0.0242 and 0.0246, respectively, both significant at the 5% level, indicating that listed companies implementing ERP systems have higher equity financing cost, indicating that overall relative value orientation still dominates. The empirical results displayed in Panel B are consistent with those in Panel A, also showing an overall increasing trend in debt financing cost. Therefore, the internal control level exerts a partial mediating effect on the impact of ERP systems adoption on the equity financing cost and debt financing cost.

6.2. Relative Value Creation Level

6.2.1. Operational Level

Listed companies implementing ERP systems exhibit higher operational efficiency (Hitt et al. 2002; Aral et al. 2006; Dehning et al. 2007; Karimi et al. 2007), and enterprises with high operational efficiency tend to have higher capital returns (Hitt et al. 2002; Hendricks et al. 2007; Dehning et al. 2007). In Panel A, column (8) presents that the coefficient of the variable ERP is positive and significant at the 1% level, suggesting that listed companies implementing ERP systems have higher operational efficiency. Column (9) presents that the coefficient of the variable Turnover is positive and significant at the 5% level, suggesting that with the improvement of operational efficiency, the equity financing cost of listed companies will increase accordingly. The coefficients of the variable ERP in columns (7) and (9) are 0.0399 and 0.0377, respectively, both significant at the 1% level, indicating that listed companies implementing ERP systems have higher equity financing costs. The empirical results displayed in Panel B are consistent with those in Panel A, also showing an overall increasing trend in debt financing cost. Thus, the operational level exerts a partial mediating effect on the impact of ERP systems adoption on equity and debt financing costs.

6.2.2. Relative Value Level

Listed companies adopting ERP systems demonstrate higher relative value (Hitt et al. 2002; Aral et al. 2006; Anderson et al. 2006), and enterprises with higher relative value tend to have higher capital returns (Hayes et al. 2001; Ranganathan and Brown 2006; Hendricks et al. 2007). In Panel A, column (11) shows that the coefficient of the variable ERP is significantly negative at the 1% level, indicating that listed companies implementing ERP systems have higher relative value. Column (12) shows that the coefficient of the variable BP [low BP value itself indicates high relative (investment) value] is significantly negative at the 1% level, indicating that with the increase in relative value, the equity financing cost of listed companies will increase accordingly. The coefficients of the variable ERP in columns (10) and (12) are 0.0232 and 0.0195, respectively, both significant at the 1% and 5% levels, indicating that listed companies implementing s have higher equity financing cost. The empirical results displayed in Panel B are consistent with those in Panel A, also showing an overall increasing trend in debt financing cost. Thus, the relative value level is the mediation effect of ERP systems implementation on the cost of equity financing and debt financing. Thus, the relative value level exerts a partial mediating effect on the impact of ERP systems adoption on equity and debt financing costs.

By examining the influence paths of the two aforementioned dimensions, it is evident that ERP can balance risks by enhancing internal control quality at the risk management level, and enhance enterprise value by improving operational efficiency at the relative value creation level, ultimately manifesting in increased financing costs or investor returns, which represents a phenomenon and result of mutual benefit and a positive cycle.

7. Heterogeneity Analysis

Using property nature (SOE) and company age (Age) as exogenous moderator variables to further validate the research question. There are two important reasons: First, unlike foreign markets, China has a large number of SOEs participating in the market, especially holding a significant position in the capital market, but they are very different from private enterprises in terms of corporate objectives and financing constraints; Second, ERP systems implementation is a capital-heavy, long-term project, and with a high risk of failure throughout the implementation process, but enterprises in different stages have varying capacities to bear the risk. Model (6) represents the moderation effect model, in which the moderator variables are uniformly denoted as “Moderator.” Table 9 presents the empirical test results of the moderation effect, and Table 10 provides a comparison of the sample sizes for the moderator variables.

ERPi,t = θ0 + θ1ERPi,t + θ2Moderatori,t + θ3ERPi,t ∗ Moderatori,t + ∑Controlsi,t + ∑Indj + ∑Yeart + εi,t

Table 9.

ERP implementation on equity financing cost and debt financing cost: moderation effect.

Table 10.

Comparison of sample sizes of moderator variables.

7.1. ERP Implementation, Property Nature, and Financing Costs of Equity and Debt

Companies are grouped according to the property nature (SOE), with non-state-owned enterprises (no-SOEs) assigned a value of 0 and SOEs assigned a value of 1. In Table 9, the regression coefficients of the interaction term ERP*SOE in columns (1) and (2) are −0.0340 and −0.0178, respectively, both significant at the 1% level, which indicates that the effects of ERP systems implementation on equity and debt financing costs are moderated by property nature: the implementation of ERP systems in SOEs will weaken their impact on equity and debt financing costs, and the moderating effect on equity financing cost is stronger than on debt financing cost.

The soft financing constraint and policy burden of SOEs lead to the deviation of enterprise value goals and risk management direction from the market, which is the main reason for this result. First of all, SOEs face weaker financing constraints due to their property rights and government guarantees, but private enterprises face more severe financial constraints than SOEs (Jin et al. 2019). This results in SOEs lacking the motivation to implement ERP systems for effective risk management and value enhancement to gain investor favor. So the result is that the implementation of ERP systems by SOEs instead suppresses investor returns.

Furthermore, SOEs bear heavier policy burdens, which leads to a misalignment between their corporate value objectives and market value objectives. Compared with private enterprises, SOEs tend to focus more on the steady operation of enterprises, and the goal of adopting ERP systems is to carry out effective internal control rather than improve efficiency and market value, which will significantly reduce the value creation function of ERP systems. However, the improvement of the risk function and the reduction in the value function lead to the reduction in investor returns. This policy burden-oriented enterprise goal will also reduce the motivation and choice of SOEs to implement ERP systems. As shown in Panel A in Table 10, both the number and proportion of ERP system implementation in SOEs are about 10 percentage points lower than that in non-SOEs, and this significant difference further strengthens the above-mentioned weakening effect.

7.2. ERP Implementation, Company Age, and Financing Costs of Equity and Debt

The variable Age was grouped according to the mean value, with companies established for a shorter period assigned a value of 0 and those established for a longer period assigned a value of 1. In Table 9, the regression coefficients of the interaction term ERP*Age_dummy in columns (3) and (4) are −0.0406 and −0.0197, respectively, both significant at the 1% level, which indicates that the impact of ERP systems implementation on equity financing cost and debt financing cost is moderated by company age: The implementation of ERP systems in long-established enterprises will weaken the impact of ERP systems implementation on equity financing cost and debt financing cost, and the moderating effect on equity financing cost is stronger than on debt financing cost.

The reason is that the later implementation of ERP systems not only prevents them from achieving the expected level of risk control and value creation but also introduces additional risks. If the life cycle of a company is divided into four stages: startup stage, growth stage, maturity stage, and decline stage (Chen and Chen 2012), then companies established for a shorter period are generally in the growth and stability stages, while those established for a longer period are in the stability and decline stages. Enterprise value and cash flow in the growth and maturity stages are higher than those in the decline stages (Dickinson 2011), and the implementation of ERP systems in this stage will significantly increase enterprise value through comprehensive risk management. However, enterprises in the decline stages generally face the dilemma of declining value and rising risk (Anthony and Ramesh 1992; Dickinson 2011), and the implementation of ERP systems is a capital-heavy, long-term, and high-risk project. The implementation of ERP projects at this stage not only fails to make marginal contributions to risk management and value creation but also increases additional costs and risks to enterprises. However, due to government subsidy interventions and fierce competition within the industry, Chinese companies will choose to implement ERP projects as a competitive advantage. As shown in Panel B in Table 10, both the number and proportion of enterprises with a long history of implementing ERP systems are much higher than those with a short history, and this significant difference further strengthens the above-mentioned weakening effect.

8. Conclusions

The implementation of ERP systems is the specific performance of the application of enterprise management ideas and is an internal strategic investment behavior of enterprises, according to the internal and external environmental situation and their own development status. Its essence is to carry out risk management and value creation for the organization, balance the risk after weighing the internal and external environment of the enterprise, achieve the sustainable value growth goal of the enterprise, and create better returns for investors. It should be emphasized that the risk is neutral, and no company blindly implements ERP systems just in order to reduce corporate risk without considering other factors; in the same way, value is relative, and companies need to trade off the value distribution among stakeholders while creating value.

Our research focuses on Chinese A-share listed companies from 2008 to 2021, examining the impact of the ERP application on equity and debt financing costs from the dual perspectives of risk management and relative value creation, grounded in the objective of maximizing corporate value. The findings suggest that, on average, enterprises implementing ERP systems exhibit significantly higher equity and debt financing costs than those not implementing such systems, with the effect on equity financing cost being more pronounced. A further exploration of the underlying causes through mechanism analysis reveals that ERP systems can enhance risk management capability and corporate value returns in a systematic, integrated, and effective way, thereby generating greater investor returns and leading to mutually beneficial outcomes. Additionally, heterogeneity analysis further shows that the ownership structure and age structure of enterprises have a significantly negative moderating effect on the above results, and the moderating effect on equity financing cost is stronger than on debt financing cost.

The deep-seated contradiction in the capital market lies in the challenge of determining whether the capital market’s functional orientation is financing-oriented or investment-oriented. Our research fundamentally alleviates the agency conflict between enterprises and investors, especially in emerging capital markets. The results emphasize the advantages of an investment-driven capital market in addressing conflicts among different participants, which can contribute to resolving challenges of “difficult and costly financing” and offer practical recommendations for policymakers. Moreover, the findings support the inverse relationship between risk and return observed in international markets with data from China’s capital market based on a managerial perspective. This provides practical clarity for both investors and managers in understanding abnormal returns within incomplete markets. Additionally, this study supports business managers in better recognizing the favorable influence of ERP systems on both corporate and financial management. It also offers valuable feedback to ERP system providers, emphasizing the necessity of aligning implementation strategies with organizational conditions and market phases to optimize outcomes. Lastly, this study investigates the Chinese market. Nevertheless, the effectiveness of the Chinese market has been weakened by government intervention. Although this factor was considered in the heterogeneity analysis, it was not systematically investigated and analyzed. Future research can overcome this limitation by employing more extensive and more diversified samples to offer richer and deeper insights.

The research conclusions have reference significance for enterprises, investors, and policymakers in the following three aspects: First, enterprises can decide whether to implement ERP projects according to their actual management level and needs, avoiding blindly following the trend. If the time is ripe, it should be planned as early as possible and gradually promoted and improved by combining corporate culture, business philosophy, and digital technology to form their own unique ERP management thoughts. Otherwise, even if an ERP system is implemented at a later stage, it may not be able to reverse the situation and achieve the expected results. Second, investors can actively focus on the financial and non-financial data of enterprises implementing ERP systems. They should pay further attention to the corporate culture and management thoughts behind these enterprises to comprehensively judge their performance, risk management level, and relative value creation level in order to obtain higher capital returns. Third, policymakers can provide enterprises with a favorable external environment for ERP implementation while avoiding excessive guidance that leads to vicious competition and overcapacity in the ERP industry. This allows enterprises to spontaneously and endogenously establish their perfect and advanced management ideological system, cultural system, and talent echelon system based on their actual situation, and then form an endogenous logical deduction ability and driving force, which can not only enhance the independent innovation capability and value creation capability of the enterprise, but also help the enterprise effectively deal with risks and crises, and also lay a solid foundation for the successful digitalization transformation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Z.; Methodology, F.M.; Software, J.Z. and F.M.; Validation, S.Z.; Formal analysis, J.Z.; Investigation, F.M.; Resources, J.Z.; Data curation, J.Z. and F.M.; Writing—original draft, J.Z.; Writing—review & editing, J.Z. and S.Z.; Visualization J.Z.; Supervision, S.Z.; Project administration J.Z.; Funding acquisition, F.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Such as “Made in China 2025” (MIC 2025) issued by the State Council in 2015 and “Guiding Opinions on Further Promoting Informatization of Small and Medium-sized Enterprises” issued by the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) in 2017, etc. |

| 2 | The STRIVE financial management model is constructed based on the following principles: enterprise (Strategy)as the guiding force, (Resource) optimization and allocation as the core, (Information) integration as the basis, management (Tools) as the means, (Efficiency) enhancement through process refinement as the objective, and enterprise (Value) maximization as the ultimate goal. |

References

- Alesina, Alberto, and Ekaterina Zhuravskaya. 2011. Segregation and the Quality of Government in a Cross Section of Countries. American Economic Review 101: 1872–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jabri, Ibrahim M., and Narcyz Roztocki. 2015. Adoption of ERP Systems: Does Information Transparency Matter? Telematics and Informatics 32: 300–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]