Natural Resource Rent and Bank Stability in the MENA Region: Does Institutional Quality Matter?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Relevant Literature and Hypotheses Development

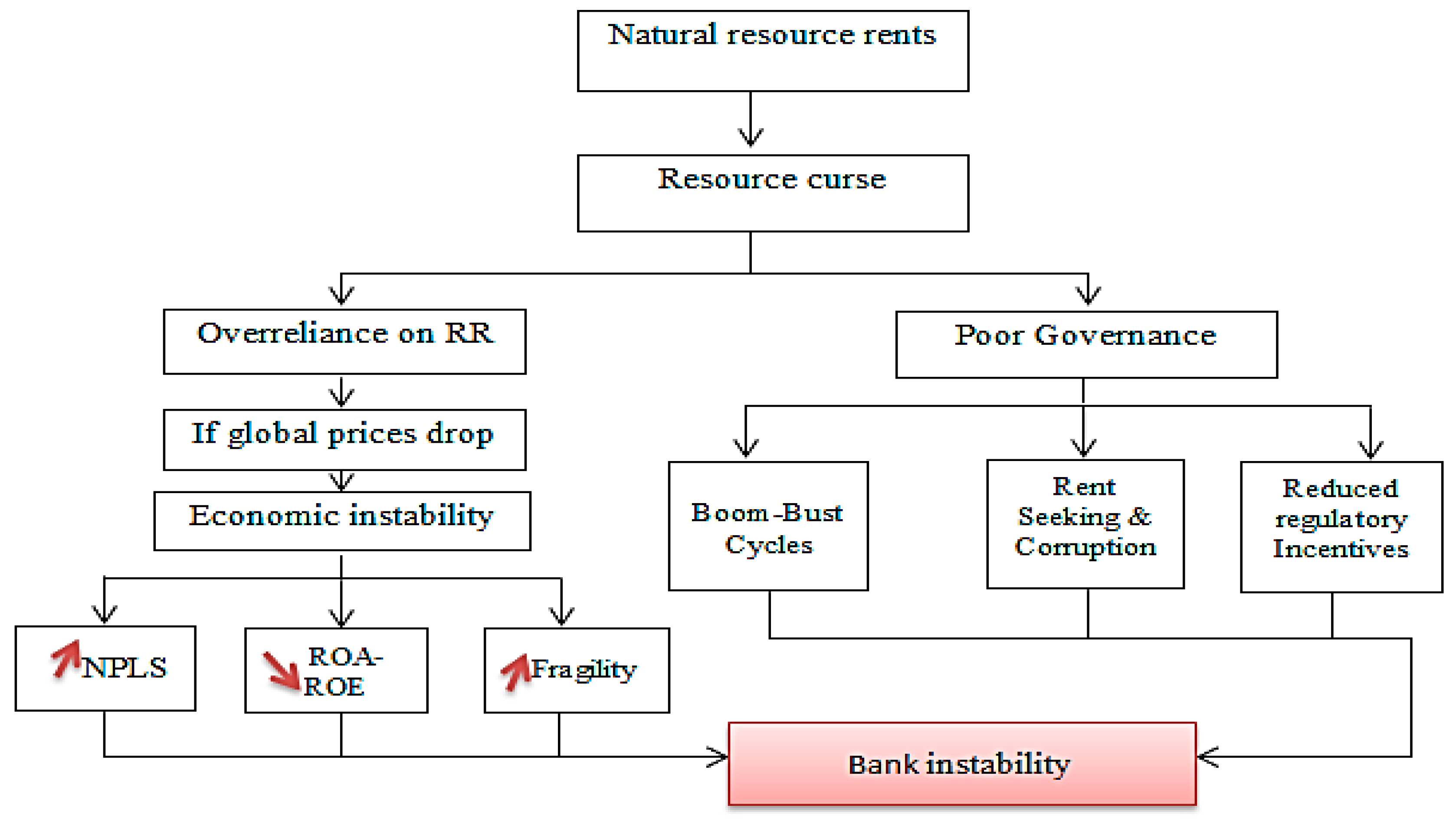

2.1. Natural Resource Rent and Bank Stability

2.2. The Moderating Role of IQ in the NRR–Bank Stability Relationship

3. Sample, Empirical Strategy, and Model Specification

3.1. Description of the Sample and Variable Selection

3.1.1. Dependent Variable: Bank Stability

3.1.2. Main Explanatory Variable: Natural Resource Rent

3.1.3. Other Explanatory Variable: Institutional Quality

3.1.4. Control Variables

3.2. Empirical Strategy and Model Specification

4. Analysis and Results

4.1. Summary Statistics and Correlation Matrix

Graphs of Summary Statistics for the Main Variables

4.2. Discussion of the Empirical Findings

4.2.1. NRR and Bank Stability

4.2.2. The Moderating Role of IQ in the NRR and Bank Stability Relationship

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adabor, Opoku, and A. Ankita Mishra. 2023. The resource curse paradox: The role of financial inclusion in mitigating the adverse effect of natural resource rent on economic growth in Ghana. Resources Policy 85: 103810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljarallah, Ruba. 2019. Impact of natural resource rents and institutional quality on human capital: A case study of the United Arab Emirates. Resources 8: 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, Franklin, Xian Gu, and Oskar Kowalewski. 2012. Financial crisis, structure and reform. Journal of Banking & Finance 36: 2960–73. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, Franklin, Yiming Qian, Guoqian Tu, and Frank Yu. 2019. Entrusted loans: A close look at China’s shadow banking system. Journal of Financial Economics 133: 18–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anginer, Deniz, Asli Demirguc-Kunt, and Min Zhu. 2014. How does competition affect bank systemic risk? Journal of Financial Intermediation 23: 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arezki, Rabah, and Markus Brückner. 2011. Oil rents, corruption, and state stability: Evidence from panel data regressions. European Economic Review 55: 955–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auty, Richard. 1993. Sustaining Development in Mineral Economies: The Resource Curse Thesis. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermpei, Theodora, Antonios Kalyvas, and Thanh Cong Nguyen. 2018. Does institutional quality condition the effect of bank regulations and supervision on bank stability? Evidence from emerging and developing economies. International Review of Financial Analysis 59: 255–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berti, Katia, Christian Engelen, and Borek Vasicek. 2017. A macroeconomic perspective on non-performing loans (NPLs). Quarterly Report on the Euro Area (QREA) 16: 7–21. [Google Scholar]

- Bilgili, Faik, Erkan Soykan, Cüneyt Dumrul, Ashar Awan, Seyit Önderol, and Kamran Khan. 2023. Disaggregating the impact of natural resource rents on environmental sustainability in the MENA region: A quantile regression analysis. Resources Policy 85 Pt A: 103825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blundell, Richard, and Stephen Bond. 1998. Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Econometrics 87: 115–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourke, Philip. 1989. Concentration and other determinants of bank profitability in Europe. North America and Australia. Journal of Banking and Finance 13: 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danisman, Gamze Ozturk, and Amine Tarazi. 2020. Financial inclusion and bank stability: Evidence from Europe. The European Journal of Finance 26: 1842–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoodi, Hamid R., and George T. Abed. 2003. Challenges of Growth and Globalization in the Middle East and North Africa. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Djebali, Nesrine, and Khemais Zaghdoudi. 2017. Bank Governance, Risk and Bank Insolvency: Evidence from Tunisian Banks. International Journal of Accounting and Financial Reporting 7: 451–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djebali, Nesrine, and Khemais Zaghdoudi. 2020. Threshold effects of liquidity risk and credit risk on bank stability in the MENA region. Journal of Policy Modeling 42: 1049–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Baomin, Yu Zhang, and Huasheng Song. 2019. Corruption as a natural resource curse: Evidence from the Chinese coal mining. China Economic Review 57: 101314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, Kumar Debasis, and Mallika Saha. 2021. Do competition and efficiency lead to bank stability? Evidence from Bangladesh. Future Business Journal 7: 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza, Mr Raphael A., and Ananthakrishnan Prasad. 2010. Nonperforming Loans in the GCC Banking System and Their Macroeconomic Effects. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Fazio, Dimas Mateus, Thiago Christiano Silva, Benjamin Miranda Tabak, and Daniel Oliveira Cajueiro. 2018. Inflation targeting and financial stability: Does the quality of institutions matter? Economic Modelling 71: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghenimi, Ameni, Hasna Chaibi, and Mohamed Ali Brahim Omri. 2017. The effects of liquidity risk and credit risk on bank stability: Evidence from the MENA region. Borsa Istanbul Review 17: 238–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakimi, Abdelaziz, and Khemais Zaghdoudi. 2017. Liquidity risk and bank performance: An empirical test for Tunisian Banks. Business Economic Research 7: 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakimi, Abdelaziz, Helmi Hamdi, and Mohamed Ali Khemiri. 2023. Banking in the MENA region: The pro-active role of financial and economic freedom. Journal of Policy Modeling 45: 1058–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, Kyung So, M.Hashem Pesaran, and Yongcheol Shin. 2003. Testing for unit roots in heterogeneous panels. Journal of Econometrics 115: 53–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imbierowicz, Björn, and Christian Rauch. 2014. The relationship between liquidity risk and credit risk in banks. Journal of Banking & Finance 40: 242–256. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn, George A., William R. Keeton, Linda Schroeder, and Stuart E. Weiner. 2003. The role of community banks in the US economy. Economic Review 88: 15–44. [Google Scholar]

- Katuka, Blessing, Calvin Mudzingiri, and Edson Vengesai. 2023. The effects of non-performing loans on bank stability and economic performance in Zimbabwe. Asian Economic and Financial Review 13: 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, Daniel, Aart Kraay, and Massimo Mastruzzi. 2011. The worldwide governance indicators: Methodology and analytical issues. Hague Journal on the Rule of Law 3: 220–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, Daniel, and Aart Kraay. 2024. The Worldwide Governance Indicators: Methodology and 2024 Update. Forthcoming in World Bank Policy Research Working Paper Series; Washington, DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Seunghyun, and Byungchul Choi. 2020. The impact of the technological capability of a host country on inward FDI in OECD countries: The moderating roles of institutional quality. Sustainability 12: 9711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, Nir. 2013. Non-Performing Loans in CESEE: Determinants and Impact on Macroeconomic Performance. IMF Working Paper Series; Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund, vol. 13, p. 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Porta, Rafael, and Florencio Lopez-de-Silanes. 1998. Capital markets and legal institutions. In Beyond the Washington consensus: Institutions Matter. Washington, DC: World Bank, vol. 73, pp. 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Laeven, Luc, and Ross Levine. 2009. Bank governance, regulation and risk taking. Journal of Financial Economics 93: 259–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, Andrew, Chien-Fu Lin, and Chia-Shang James Chu. 2002. Unit root tests in panel data: Asymptotic and finite-sample properties. Journal of Econometrics 108: 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddala, Gangadharrao S., and Shaowen Wu. 1999. A Comparative Study of Unit Root Tests and a New Simple Test. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics 61: 631–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeay, Michael, Amar Radia, and Ryland Thomas. 2014. Money Creation in the Modern Economy. London: Bank of England. [Google Scholar]

- Mehlum, Halvor, Karl Moene, and Ragnar Torvik. 2006. Cursed by resources or institutions? World Economy 29: 1117–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercieca, Steve, Klaus Schaeck, and Simon Wolfe. 2007. Small European banks: Benefits from diversification? Journal of Banking & Finance 31: 1975–98. [Google Scholar]

- Molyneux, Philip, and John Thornton. 1992. Determinants of European Bank Profitability: A Note. Journal of Banking and Finance 16: 1173–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moudud-Ul-Huq, Syed, Changjun Zheng, Anupam Das Gupta, SK Alamgir Hossain, and Tanmay Biswas. 2023. Risk and performance in emerging economies: Do bank diversification and financial crisis matter? Global Business Review 24: 663–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muizzuddin, Muizzuddin, Eduardus Tandelilin, Mamduh Mahmadah Hanafi, and Bowo Setiyono. 2021. Does institutional quality matter in the relationship between competition and bank stability? Evidence from Asia. Journal of Indonesian Economy and Business 36: 283–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niftiyev, Ibrahim. 2022a. A comparison of institutional quality in the South Caucasus: Focus on Azerbaijan. In Proceedings of the European Union’s Contention in the Reshaping Global Economy. Edited by Juhász Judit. Szeged: University of Szeged, Faculty of Economics and Business Administration, Doctoral School in Economics, pp. 146–75. ISBN 978-963-306-852-6. Available online: http://eco.u-szeged.hu/download.php?docID=128206 (accessed on 18 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Niftiyev, Ibrahim. 2022b. Principal component and regression analysis of the natural resource curse doctrine in the Azerbaijani economy. Journal of Life Economics 9: 225–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, Douglass C. 1990. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nurmakhanova, Mira, Mohamed Elheddad, Abdelrahman J. K. Alfar, Alloysius Egbulonu, and Mohammad Zoynul Abedin. 2023. Does natural resource curse in finance exist in Africa? Evidence from spatial techniques. Resources Policy 80: 103151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragmoun, Wided. 2023. Ecological footprint, natural resource rent, and industrial production in MENA region: Empirical evidence using the SDM model. Heliyon 9: e20060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, Raghuram G., and Luigi Zingales. 2003. The great reversals: The politics of financial development in the twentieth century. Journal of Financial Economics 69: 5–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, James A., Ragnar Torvik, and Thierry Verdier. 2006. Political foundations of the resource curse. Journal of Development Economics 79: 447–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, Jeffrey, and Andrew Warner. 1995. Natural Resource Abundance and Economic Growth. NBER Working Paper Series; Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, Jeffrey D., and Andrew M. Warner. 2001. The curse of natural resources. European Economic Review 45: 827–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, Khalid Adnan. 2021. Revisiting the natural resource curse: Across-country growth study. Cogent Economics & Finance 9: 2000555. [Google Scholar]

- Schinasi, Garry J. 2004. Defining Financial Stability, IMF Working Paper, WP/04/187. Available online: https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2004/wp04187.pdf (accessed on 11 January 2025).

- Sedighi, Somayeh, and Ibrahim Niftiyev. 2024. Economic Growth through Rent Streams, Financial Development and Institutional Quality in Mena. Finance: Theory and Practice 30: 1706-01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Chandan, and Ritesh Kumar Mishra. 2022. On the Good and Bad of Natural Resource, Corruption, and Economic Growth Nexus. Environmental and Resource Economics 82: 889–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srairi, Samir. 2013. Ownership structure and risk-taking behaviour in conventional and Islamic banks: Evidence for MENA countries. Borsa Istanbul Review 13: 115–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, Aurora AC, and Anabela SS Queirós. 2016. Economic growth, human capital and structural change: A dynamic panel data analysis. Research Policy 45: 1636–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torvik, Ragnar. 2002. Natural resources, rent seeking and welfare. Journal of Development Economics 67: 455–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaghdoudi, Khemais. 2019. The effects of risks on the stability of Tunisian conventional banks. Asian Economic and Financial Review 9: 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Kaiguo. 2014. The effect of income diversification on bank risk: Evidence from China. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade 50: 201–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Middle East North Africa Countries | Bank Stability | Natural Resource Rents | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Countries | Number of Banks | % | Bank Z-Score (*1) | NRR in % of GDP (*2) |

| Jordan | 13 | 19.11% | 52.464 | 1.59 |

| Kuwait | 5 | 7.35% | 16.607 | 46.55 |

| Oman | 3 | 4.41% | 17.583 | 33.13 |

| Lebanon | 4 | 5.88% | 17.853 | 0.001 |

| Qatar | 4 | 5.88% | 24.979 | 29.31 |

| Saudi Arabia | 8 | 11.76% | 19.639 | 37.90 |

| United Arab Emirates | 13 | 19.11% | 25.538 | 21.58 |

| Egypt | 4 | 5.88% | 17.745 | 9.24 |

| Morocco | 4 | 5.88% | 38.995 | 3.30 |

| Tunisia | 10 | 14.70% | 32.663 | 4.86 |

| Number of banks | 68 | 100% | Average = 26.40 | Average = 18.74% |

| Variables | Definitions | Measures |

|---|---|---|

| Dependent variables (BSTAB) | ||

| Z-score (ROA) | Bank stability | The ratio of the sum of the averaged ROA and the CAP to the standard deviations of ROA. |

| Z-score (ROE) | Bank stability | The mean of return on equities plus the capital adequacy ratio divided by the standard deviation of return on equities |

| Natural Resource Rent and Institutional Quality | ||

| NRR | Natural Resource Rent | The total natural resource rents expressed as a percentage of GDP |

| IQ | Institutional quality | An index of IQ (see Kaufmann et al. 2011) |

| NRR*IQ | Interactional variable | The interaction between NRR and IQ |

| Bank specifics | ||

| BS | Bank size | Natural logarithm of total assets |

| CAR | Capital adequacy ratio | Bank capital to total assets (%) |

| ROA | Return on assets | Net income after tax to total assets |

| LTD | Liquidity risk | Loan-to-deposit ratio (%) |

| NPLs | Non-performing loans | Bank non-performing loans to gross loans (%) |

| Industry specifics | ||

| CONC | Bank Concentration | Bank concentration (%) |

| LERN | Bank competition | The Lerner index |

| Financial environment and macroeconomic conditions | ||

| GDPG | The growth rate of GDP | Annual growth rate of GDP (%) |

| INF | The inflation rate | Consumer price index (%) |

| CRISIS | Global financial crisis of 2008 | Dummy variable that takes 0 before the crisis of 2008 and 1 after. |

| UNEM | The unemployment rate | The unemployment rate (%) |

| Variable | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LNZROA | 2.657 | 0.860 | −2.798 | 4.431 |

| LNZROE | 1.303 | 0.655 | −1.269 | 3.229 |

| NRR | 16.925 | 16.743 | 0.001 | 59.069 |

| IQ | −0.038 | 0.417 | −1.008 | 0.724 |

| BS | 9.887 | 2.660 | 5.045 | 18.080 |

| CAR | 14.869 | 4.941 | 1.256 | 40.350 |

| ROA | 1.954 | 3.505 | −10.304 | 101.432 |

| LTD | 82.676 | 27.869 | 1.438 | 215.322 |

| NPLs | 8.267 | 7.692 | 0.010 | 58.130 |

| CONC | 67.906 | 19.267 | 40.218 | 100.000 |

| LERN | 0.423 | 0.109 | 0.098 | 0.615 |

| GDPG | 3.225 | 4.465 | −21.464 | 26.170 |

| INF | 3.955 | 6.403 | −4.863 | 84.864 |

| UNEM | 1.954 | 3.505 | −10.304 | 101.432 |

| CRISIS | 0.812 | 0.390 | 0 | 1 |

| NRR | IQ | BS | CAR | ROA | LTD | NPLs | CONC | LERN | GDPG | INF | CRISIS | UNEM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NRR | 1.0000 | ||||||||||||

| IQ | 0.2951 * | 1.0000 | |||||||||||

| 0.0000 | |||||||||||||

| BS | −0.0086 | −0.2628 * | 1.0000 | ||||||||||

| 0.7776 | 0.0000 | ||||||||||||

| CAR | 0.1849 * | 0.2309 * | 0.0073 | 1.0000 | |||||||||

| 0.0000 | 0.0021 | 0.8091 | |||||||||||

| ROA | 0.0185 | −0.0031 | −0.0398 | 0.2474 * | 1.0000 | ||||||||

| 0.5415 | 0.9178 | 0.1902 | 0.0000 | ||||||||||

| LTD | 0.0873 * | 0.2992 * | −0.3316 * | −0.2009 * | −0.0567 | 1.0000 | |||||||

| 0.0086 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0885 | |||||||||

| NPLs | −0.2634 * | −0.1236 * | −0.2635 * | −0.2331 * | −0.0349 | 0.1971 * | 1.0000 | ||||||

| 0.0000 | 0.0010 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.3536 | 0.0000 | ||||||||

| CONC | 0.0404 | 0.1250 * | −0.1930 * | 0.0556 | 0.0659 * | −0.0866 * | −0.0205 | 1.0000 | |||||

| 0.1827 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0668 | 0.0297 | 0.0092 | 0.5862 | |||||||

| LERN | 0.7070 * | 0.5357 * | −0.2379 * | 0.2359 * | 0.1091 * | 0.1673 * | −0.2673 * | 0.1586 * | 1.0000 | ||||

| 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0054 | 0.0003 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | ||||||

| GDPG | 0.1836 * | 0.1372 * | −0.0843 * | 0.0304 | 0.1135 * | −0.0611 | −0.0590 | 0.0101 | −0.0022 | 1.0000 | |||

| 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0054 | 0.3168 | 0.0002 | 0.0666 | 0.1178 | 0.7398 | 0.9562 | |||||

| INF | −0.0465 | −0.2962 * | 0.0820 * | −0.0904 * | 0.0068 | −0.2014 * | 0.1552 * | 0.1356 * | −0.2422 * | −0.1157 | 1.0000 | ||

| 0.1350 | 0.0000 | 0.0083 | 0.0037 | 0.8270 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0002 | ||||

| CRISIS | −0.1057 * | −0.0232 | 0.1239 * | −0.0648 * | −0.1090 * | 0.0357 | −0.1439 * | 0.0733 * | 0.1573 * | −0.3571 * | −0.0322 | 1.0000 | |

| 0.0005 | 0.4450 | 0.0000 | 0.0327 | 0.0003 | 0.2838 | 0.0001 | 0.0155 | 0.0001 | 0.0000 | 0.3009 | |||

| UNEM | −0.7084 * | −0.5206 * | −0.3580 * | −0.2391 * | 0.0302 | 0.0262 | 0.2607 * | −0.0581 | −0.4822 * | −0.1384 * | 0.0817 * | 0.0150 | 1.0000 |

| 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.3199 | 0.4314 | 0.0000 | 0.0555 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0086 | 0.6217 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | VIF | 1/VIF | Variable | VIF | 1/VIF |

| NRR | 5.13 | 0.194 | UNEM | 5.14 | 0.194 |

| LERN | 4.16 | 0.240 | LERN | 3.10 | 0.322 |

| UNEM | 4.07 | 0.245 | BS | 2.91 | 0.344 |

| BS | 2.60 | 0.384 | NRR*IQ | 2.18 | 0.458 |

| CONC | 2.05 | 0.486 | LTD | 2.09 | 0.477 |

| LTD | 1.90 | 0.525 | CONC | 2.06 | 0.485 |

| CAR | 1.75 | 0.570 | CAR | 1.72 | 0.580 |

| NPLS | 1.65 | 0.604 | NPLS | 1.65 | 0.607 |

| CRISIS | 1.51 | 0.664 | CRISIS | 1.57 | 0.635 |

| ROA | 1.49 | 0.672 | NRR | 1.51 | 0.725 |

| INF | 1.37 | 0.730 | ROA | 1.48 | 0.674 |

| GDPG | 1.18 | 0.846 | IQ | 1.29 | 0.620 |

| INF | 1.26 | 0.792 | |||

| GDPG | 1.22 | 0.822 | |||

| Mean VIF | 2.41 | Mean VIF | 2.08 | ||

| LLC (2002) t * | IPS (2003) W-Stat | ADF-Fisher (MW, 1999) Chi-Square | |

|---|---|---|---|

| LNZROA | −2.50379 * (0.06928) | 2.10789 (0.9825) | 48.755 ** (0.0214) |

| LNZROE | −1.52762 * (0.0633) | −0.73301 (0.2318) | 186.419 *** (0.0027) |

| NRR | −2.64772 *** (0.0041) | 66.7149 * (0.0762) | 96.3090 (0.9960) |

| IQ | −2.17113 ** (0.0150) | 5.95364 * (0.0829) | 103.431 (0.9829) |

| BS | −12.3291 *** (0.0000) | −4.37312 *** (0.0000) | 248.237 *** (0.0000) |

| CAR | −2.33264 *** (0.0098) | −0.51402 (0.3036) | 179.061 *** (0.0057) |

| ROA | −11.7177 *** (0.0000) | −4.81784 *** (0.0000) | 239.340 *** (0.0000) |

| LTD | −21.6178 *** (0.0000) | −5.89156 *** (0.0000) | 217.333 *** (0.0000) |

| NPLs | −43.0370 *** (0.0000) | −4.09924 *** (0.0000) | 136.210 ** (0.0345) |

| CONC | −2.3712 * (0.0991) | 6.01301 * (0.07850) | 58.5298 (0.76321) |

| LERN | −9.96446 *** (0.0000) | −3.90457 *** (0.0000) | 174.629 *** (0.0039) |

| CDPG | −3.06114 ** (0.0489) | 20.4640 * (0.0993) | 100.481 (0.9902) |

| INF | −2.56089 * (0.0694) | −0.44988 (0.3264) | 115.829 * (0.0894) |

| CRISIS | −18.4457 *** (0.0000) | −12.3550 *** (0.0000) | 394.194 *** (0.0000) |

| UNEM | −7.03310 ** (0.0449) | −4.32586 * (0.0887) | 107.495 (0.9660) |

| Z-Score (ROA) | Z-Score (ROE) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | Std. Err. | Z | P > z | Coef. | Std. Err. | Z | P > z | |

| LnZROA(-1) | 0.764 | 0.013 | 56.23 | 0.000 *** | - | - | - | - |

| LnZROE(-1) | - | - | - | - | 0.477 | 0.001 | 40.87 | 0.000 *** |

| NRR | −0.002 | 0.0004 | −4.16 | 0.000 *** | −0.003 | 0.001 | −3.33 | 0.001 *** |

| BS | 0.034 | 0.100 | 3.46 | 0.001 *** | 0.152 | 0.012 | 12.02 | 0.000 *** |

| CAR | 0.038 | 0.001 | 35.67 | 0.000 *** | 0.023 | 0.001 | 18.41 | 0.000 *** |

| ROA | 0.099 | 0.003 | 29.65 | 0.000 *** | 0.097 | 0.004 | 19.93 | 0.000 *** |

| LTD | −0.001 | 0.0001 | −6.22 | 0.000 *** | −0.002 | 0.0002 | −6.68 | 0.000 *** |

| NPLs | −0.006 | 0.0007 | −7.64 | 0.000 *** | −0.002 | 0.0008 | −2.39 | 0.017 ** |

| CONC | −0.001 | 0.001 | −0.89 | 0.373 | 0.010 | 0.0008 | 11.59 | 0.000 *** |

| LERN | 0.031 | 0.138 | 0.23 | 0.818 | 0.865 | 0.108 | 7.97 | 0.000 *** |

| GDPG | 0.003 | 0.000 | 3.59 | 0.000 *** | 0.006 | 0.001 | 5.18 | 0.000 *** |

| INF | 0.0009 | 0.001 | 0.93 | 0.353 | 0.0005 | 0.001 | 0.52 | 0.601 |

| CRISIS | −0.077 | 0.007 | −11.05 | 0.000 *** | −0.227 | 0.010 | −21.47 | 0.000 *** |

| UNEM | −0.022 | 0.002 | −7.83 | 0.000 *** | −0.011 | 0.001 | −6.54 | 0.000 *** |

| _cons | 0.417 | 0.136 | 3.06 | 0.002 *** | 1.905 | 0.160 | 11.86 | 0.000 *** |

| AR(1) | −1.1277 | −2.2102 | ||||||

| Prob | 0.2594 | 0.0271 | ||||||

| AR(2) | 0.7835 | −1.2872 | ||||||

| Prob | 0.3824 | 0.1980 | ||||||

| Sargan test | 46.757 | 46.784 | ||||||

| Prob | 0.3208 | 0.3198 | ||||||

| Obs | 968 | 968 | ||||||

| Z-Score (ROA) | Z-Score (ROE) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | Std. Err. | Z | P > z | Coef. | Std. Err. | Z | P > z | |

| LnZROA(-1) | 0.776 | 0.013 | 58.11 | 0.000 *** | - | - | - | - |

| LnZROE(-1) | - | - | - | - | 0.468 | 0.013 | 33.90 | 0.000 *** |

| NRR | −0.001 | 0.0003 | −3.21 | 0.000 *** | −0.002 | 0.001 | −4.71 | 0.001 *** |

| IQ | 0.074 | 0.019 | 3.83 | 0.000 *** | 0.048 | 4.818 | 8.48 | 0.000 *** |

| NRR*IQ | 0.001 | 0.0002 | 4.16 | 0.000 *** | 0.005 | 0.0007 | 6.34 | 0.000 *** |

| BS | 0.035 | 0.007 | 4.85 | 0.000 *** | 0.149 | 0.012 | 11.52 | 0.000 *** |

| CAR | 0.037 | 0.001 | 31.25 | 0.000 *** | 0.022 | 0.001 | 14.07 | 0.000 *** |

| ROA | 0.100 | 0.002 | 34.99 | 0.000 *** | 0.093 | 0.004 | 20.37 | 0.000 *** |

| LTD | −0.001 | 0.0001 | −5.71 | 0.000 *** | −0.001 | 0.0001 | −7.62 | 0.000 *** |

| NPLs | −0.007 | 0.001 | −7.18 | 0.000 *** | −0.001 | 0.0007 | −1.39 | 0.163 |

| CONC | −0.001 | 0.001 | −0.98 | 0.329 | 0.008 | 0.0008 | 9.43 | 0.000 *** |

| LERN | −0.089 | 0.086 | −1.03 | 0.303 | 0.704 | 0.105 | 6.66 | 0.000 *** |

| GDPG | 0.005 | 0.0006 | 7.74 | 0.000 *** | 0.005 | 0.001 | 4.99 | 0.000 *** |

| INF | 0.001 | 0.017 | 0.29 | 0.768 | −0.0001 | 0.001 | −0.17 | 0.864 |

| CRISIS | −0.072 | 0.003 | −19.14 | 0.000 *** | −0.226 | 0.013 | −17.30 | 0.000 *** |

| UNEM | −0.016 | 0.002 | −6.94 | 0.000 *** | −0.003 | 0.002 | −1.43 | 0.153 |

| _cons | 0.352 | 0.125 | 2.80 | 0.005 *** | 1.713 | 0.158 | 10.84 | 0.000 *** |

| AR(1) | −1.0806 | −2.3212 | ||||||

| Prob | 0.2799 | 0.0203 | ||||||

| AR(2) | 0.8471 | −1.2698 | ||||||

| Prob | 0.3969 | 0.2042 | ||||||

| Sargan test | 46.766 | 50.222 | ||||||

| Prob | 0.3205 | 0.2090 | ||||||

| Obs | 968 | 968 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hakimi, A.; Saidi, H.; Khemiri, M.A. Natural Resource Rent and Bank Stability in the MENA Region: Does Institutional Quality Matter? Risks 2025, 13, 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks13060101

Hakimi A, Saidi H, Khemiri MA. Natural Resource Rent and Bank Stability in the MENA Region: Does Institutional Quality Matter? Risks. 2025; 13(6):101. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks13060101

Chicago/Turabian StyleHakimi, Abdelaziz, Hichem Saidi, and Mohamed Ali Khemiri. 2025. "Natural Resource Rent and Bank Stability in the MENA Region: Does Institutional Quality Matter?" Risks 13, no. 6: 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks13060101

APA StyleHakimi, A., Saidi, H., & Khemiri, M. A. (2025). Natural Resource Rent and Bank Stability in the MENA Region: Does Institutional Quality Matter? Risks, 13(6), 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks13060101