1. Introduction

The Islamic Financial Services Industry (IFSI) is a recent development as a distinct stream of financing aimed at adhering to Shari’ah (Islamic law) precepts within the global financial system. IFSI has replaced existing financial contracts with Shari’ah-compliant instruments. IFSI has expanded worldwide, primarily in Muslim societies. The asset volume under management of IFSI reached approximately USD 3.25 trillion in 2022, the majority being in the banking sector (

IFSBr 2023). The industry has attracted the attention of the finance community beyond religious affiliations due to built-in strengths (including asset-based financing and profit and loss sharing, etc.). The establishment of the Shari’ah Supervisory Board (SSB) as another tier of corporate governance is recommended for an organization that intends to offer IFSI-approved financial contracts used in business.

Although some practices contradictory to Shari’ah were primary concerns under the conventional financial system, IFSI has specific objectives as documented in the literature. The contradictory practices under conventional finance are

Riba (charging interest in financial transactions) (

Al-Qur’an n.d., 2: 275–281);

Maisir (gambling) and

Qimar (betting);

Gharar (higher degree of uncertainty in outcome) (

Atikullah 2017); and facilitation of prohibited (

Haram) activities. IFSI carries a positive list of specific objectives (including promoting equitability in wealth distribution, financial stability, and social uplift) in addition to a negative checklist.

Now that IFSI has surpassed the age of 40, evaluating the industry based on its aspirational objectives and claims (including, but not limited to, financial stability, equitable wealth distribution, and contributions towards social uplift) is appropriate. Performance evaluation is an essential aspect of organizational life for documenting deviations from stated objectives and setting the direction of an entity for the future. Traditionally, financial institutions are evaluated using the CAMELS framework, which covers capital adequacy, asset quality, management capabilities, earnings, liquidity, and sensitivity. The performance of IFSI needs to be evaluated in light of the expressly stated objectives that justify the existence of a separate financial system. Hence, the existing financial performance evaluation framework for the conventional financial sector is inappropriate for evaluating IFSI, as it lacks coverage of specific Islamic finance objectives. The existing framework is helpful for documenting the commercial performance of IFSI, which needs to be enhanced/expanded to include specific Islamic finance objectives.

A number of existing studies evaluate the financial performance of several IFSI markets by using the existing framework (see, inter alia,

Hanif et al. 2012;

Islam and Ashrafuzzaman 2015); however, studies covering extended Islamic finance objectives are rare. Based on specific objectives of the Islamic financial system, some valuable efforts have been made in the area of the development of a performance evaluation framework for IBSI (e.g.,

Mohammed et al. 2015;

Mergaliyev et al. 2021;

Tarique et al. 2021;

Hanif and Ayub 2022). Another related stream in the literature focuses on the development of Shari’ah compliance ratings for IBSI, considering IFSI objectives (

Ashraf and Lahsasna 2017;

Hanif 2018). The literature lacks evidence on the achievements of specific Islamic financial objectives in multiple IBSI markets, including the GCC region, apart from critical evaluation of suggested performance evaluation frameworks for IFSI. The closest effort to this research is done by

Hanif and Farooqi (

2023), by documenting the achievements of Pakistani IBSI. Hence, a literature gap exists regarding global IBSI achievements in the area of aspirational objectives. In this study, we focus on the achievements of the United Arab Emirates (UAE) IBSI by studying accounting data for 33 quarters (2013 Q4–2021 Q4).

The study is expected to yield multiple contributions to the literature. Specifically, the following are the research objectives: First, to identify Islamic finance objectives with rankings (primary, intermediate, and advanced) based on a literature review. Second, to elaborate a performance evaluation framework that is measurable using exclusively publicly available financial reports. Finally, the paper aims to document the achievements in the areas of financial stability, equitable wealth distribution, and commercial performance of UAE-IBSI (an early adopter and systemically important market).

The methodology includes balance sheet analysis, which involves objectively classifying data as sources and uses of funds, with a focus on the application of financial contracts, distinguishing between debt-based and equity-based sources.

The rest of the study proceeds in the following order: The next section presents a selected literature review, followed by the methodology.

Section 4 presents analysis and document findings, while the last section concludes the research.

2. Literature Review

Religious lenses highlight the existence of some questionable practices in the conventional financial system, including

Riba, Maisir,

Qimar,

Gharar, and financing for

Haram activities. In addition to its prohibitions, IFSI aspires to promote financial stability, equity in wealth distribution, and social uplift of unserved and underserved segments of society. The

World Bank (

2023) defines financial stability as follows:

“A stable financial system is capable of efficiently allocating resources, assessing and managing financial risks, maintaining employment levels close to the economy’s natural rate, and eliminating relative price movements of real or financial assets that will affect monetary stability or employment levels.”

Fairness in the distribution of income and wealth, along with the provision of equal opportunities to all participants, are the hallmarks of equitable wealth distribution. A contribution to financial stability is expected by linking real and financial sectors. Debt increment in the economy is linked with an increase in actual output (

Chapra 2008). IFSI offers multiple asset-based financing contracts, providing debt to commerce and industry, including

Murabaha (mark-up sale),

Salam and

Istisna’a (forward selling), and

Ijarah (leasing). Profit and Loss Sharing (PLS) contracts aim to distribute the actual value created or destroyed among the participants. According to Shari’ah, profits are shared as per the pre-agreed sharing ratio among the partners; however, losses follow the capital, and the pre-agreed loss-sharing ratio cannot be different from equity stakes (

Hanif 2020). Multiple financing contracts based on the principles of PLS are available to global IFSI, including

Musharakah (partnership in capitals),

Mudarabah (partnership in capital and skill), and diminishing

Musharakah (gradually declining partnership). PLS contracts and access to finance are expected to contribute to achieving equitability in wealth distribution (

Chapra 2008). Social uplift is expected to be fulfilled through the provision of financing to social sectors, including education and health services, Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs), agriculture and rural financing,

qarḍ e hasan (zero return loans), as well as playing an active role in the management of charity funds including

Waqf (objective-based charity) and

Zakah (compulsory charity by wealthy Muslims) (

AAOIFI 2015).

What are the achievements of modern IFSI as far as the positive checklist is concerned? It is an important question that needs to be addressed. To evaluate the performance of IFSI, a framework is required that aligns with its specific objectives. There are some worthy efforts in the literature in this regard. For example, considering the five dimensions of Imam Ghazali’s

Maqasid Al Shari’ah theory (protection of faith, life, lineage, property, and intellect),

Mohammed et al. (

2015) developed the

Maqāṣid-based Performance Evaluation Model (MPEM) for Islamic banks. Accordingly, Islamic banks are encouraged to apply risk–reward sharing financial contracts, pay

Zakah, reduce/eliminate

Haram income, reduce/eliminate employee turnover, and generate profit, as well as invest more in CSR, SMEs, research and training, the real sector, agriculture, technology, etc. Another attempt to develop a performance evaluation model for Islamic banks was made by

Mergaliyev et al. (

2021) based on Najjar’s extended

Maqasid framework. The model includes eight corollaries and four primary objectives. Suggested courses of action include social goals including charity,

qarḍ e hasan,

waqf,

Zakah, environmental protection, grants for education and research, in addition to economic goals aimed at employment creation, fair returns (earnings), engagement in risk–reward sharing,

Halal earnings, investment in the real sector, microfinancing, returns to depositors and shareholders, and fairness and transparency (in employment policies, corporate governance practices), etc. The performance evaluation framework developed by

Hanif and Ayub (

2022) groups IFSI objectives into three broader areas, including social justice, economic objectives and legal compliance. However, the authors have not provided detailed findings on any IBSI market, instead presenting summary results of global IBSI. This research intends to enhance the work of

Hanif and Ayub (

2022) by documenting findings on the UAE—an early adopter and a systemically important IBSI market. Another notable theme in the literature is the area of Shari’ah compliance ratings for IBSI (

Ashraf and Lahsasna 2017;

Hanif 2018). The authors attempted to suggest a ranking mechanism for IBSI by identifying key scoring factors, including capital adequacy, regulatory framework, Shari’ah governance, access to finance, portfolio composition, and reputation, among others.

Regarding the documentation of IBSI’s achievements, conventional methods have been employed, and specific studies document the empirical financial performance of IBSI globally, including the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), South Asia, and Southeast Asia, among others. In Southeast Asian IBSI, comparative performance evaluation of conventional and Islamic banking has been conducted by some studies (e.g.,

Rosly and Bakar 2003;

Kamaruddina et al. 2008;

Rozzani and Rahman 2013;

Hazman et al. 2018). The results from studies of Southeast Asian IBSI are inconclusive regarding the comparative performance of both banking streams, namely conventional and Islamic. IBSI led in some performance areas but lagged in others.

A brief review of the findings of the studies conducted on South Asian IBSI is presented below. Several studies are worth mentioning that aim to compare the performance evaluation of South Asian markets, including those for Bangladesh (

Mahmud and Islam n.d.;

Ahmad and Hassan 2007;

Islam and Ashrafuzzaman 2015). Findings indicate either better performance or performance equivalent to that of conventional banking. In Pakistani institutional settings, the following studies have been conducted:

Moin 2008;

Ansari and Rehman 2011;

Hanif et al. 2012;

Usman and Khan 2012;

Latif et al. 2016;

Qureshi and Abbas 2019;

Abideen 2019. Although the findings are mixed, Islamic banking depicts superior management in the areas of solvency and risk. Additionally, Islamic banking has shown improved profitability over the period, as indicated by relevant studies.

Hanif and Farooqi (

2023) present findings on Pakistani IBSI in light of specific Islamic finance objectives, utilizing quarterly financial reporting data from Q4 2013 to Q3 2021. The results support achievements in two areas: commercial performance and contribution to economic objectives, including wealth distribution and financial stability. However, progress on contribution to social uplift and access to financing remained slight.

The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) are at the center of the stage in the IFSI landscape. MENA includes the GCC region, and the share of GCC in assets under the management of global IFSI is close to half of the industry size (

IFSBr 2023). Some studies have compared the financial performance of conventional and Islamic banking sectors, covering profitability, liquidity, credit risk and solvency (Bahrain (

Samad 2004); Jordan (

Saleh and Zeitun 2007); Egypt (

Fayed 2013); GCC (

Siraj and Pillai 2012)).

Virk et al. (

2022) document that improvement in financial performance is attributed to the presence of a higher proportion of prominent Shari’ah scholars on the Shari’ah Supervisory Board (SSB) in the GCC region IBSI. However,

Alshammari (

2022) finds a significant positive impact of state ownership on the performance of conventional banking but not in the case of GCC IBSI. On the front of comparative efficiency,

Khokhar et al. (

2020) document equality in all terms of efficiency between conventional and Islamic banking in GCC. Except for the Egyptian market, IBSI exhibits either equality with conventional banking or better performance. Also, GCC IBSI turned out to be more resilient than conventional banking to the global financial crisis (

Siraj and Pillai 2012).

To the best of our knowledge, irrespective of methodological issues, the studies cited have documented financial performance but are lacking in evaluation based on broader Islamic finance objectives, except for the study on Pakistani IBSI by

Hanif and Farooqi (

2023). The present study aims to contribute to the literature by evaluating the UAE IBSI based on aspirational Islamic finance objectives, including economic objectives (equitable wealth distribution and financial stability) and commercial performance within Shari’ah constraints.

Islamic Finance Objectives: Islamic finance seeks to integrate the Abrahamic religious values of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam into the financial system (

Abdulrahman 2010). Over the years, scholars have made numerous efforts to identify specific objectives for the Islamic financial system. A number of studies have based the identification of the Islamic financial system on the

Maqasid Al-Shari’ah (objectives of Islamic law). The objectives of Shari’ah, as documented by Ghazali and later developed by multiple other scholars, including Al-Najjar, are neither explicitly stated in the Qur’an nor in the Sunnah. However, they are inferred by Muslim philosophers from the teachings of the Qur’an and Sunnah. Ghazali documents five priority areas for Muslim society to protect individual rights (

Mohammed et al. 2015), including the protection of faith, life, lineage, wealth, and intellect. Syed Mawdoodi (Pakistan) and Sayed Qutb (Egypt) were earlier proponents of the Islamic financial system (

Maudoodi 1941;

Abdulrehman 2000) and advocated socioeconomic justice. Equitability in wealth distribution and financial stability are expected from a just economic system (

Chapra 2008). Operationalization, as suggested by the author, encompasses the application of risk–reward sharing, access to finance, and the integration of real and financial sectors. In light of the developments in the relevant literature,

Hanif and Ayub (

2022) identified three broader areas, including legal compliance, economic objectives and social objectives.

Hanif and Farooqi (

2023) further extend the model by adding the fourth aspect of commercial performance, in addition to Shari’ah compliance, broader economic objectives and social justice. In this study, we aim to document achievements in two key areas: economic objectives and commercial performance in the UAE Islamic banking industry, utilizing published financial reports.

3. Methodology

Given the differences in objectives between conventional and Islamic financial systems, the conventional performance evaluation framework needs extension and improvement for documenting progress on the achievements of the IBSI (

Mohammed et al. 2015;

Mergaliyev et al. 2021;

Hanif and Ayub 2022).

Saleh and Zeitun (

2007) suggest a different framework for performance evaluation of IBSI by considering specific objectives (and categorizing banking objectives as core and additional/others). Profit maximization is a core objective; other objectives for IBSI include fostering well-being (economic and social) and eliminating exploitation (p. 48).

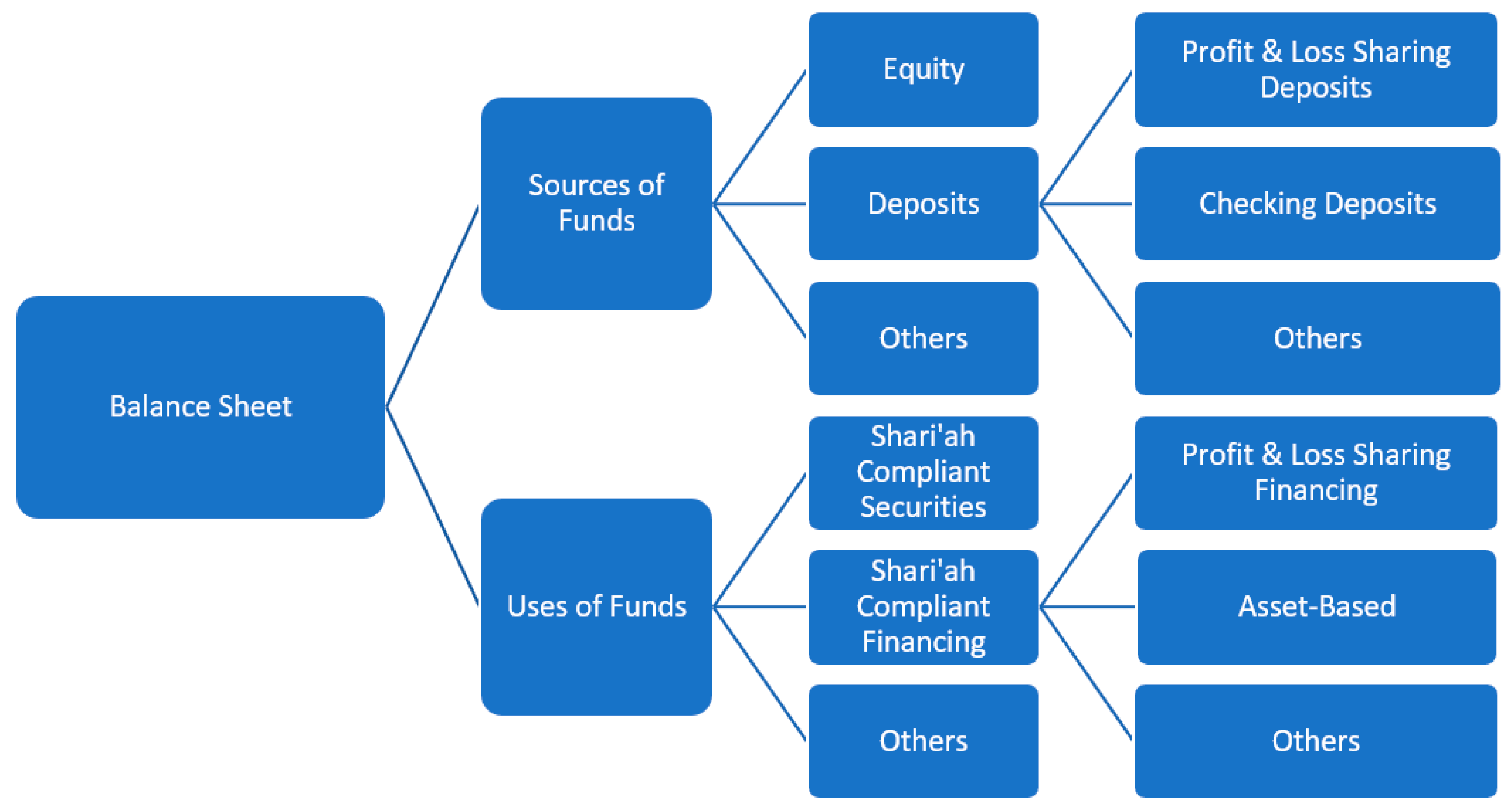

Figure 1 presents a performance evaluation framework for IBSI considering Islamic finance objectives. The objectives are classified as micro and macro objectives.

Micro Objectives: Micro objectives include Shari’ah compliance and commercial performance. Shari’ah compliance is the raison d’être of IBSI (

Hanif and Ayub 2022), in addition to local commercial laws. Similarly, competitive commercial performance is crucial for the long-term sustainability of the industry. Efficiency, profitability, solvency and liquidity are equally desired for IBSI (

Saleh and Zeitun 2007).

Macro Objectives: Macro objectives include social and broader economic objectives. Contributions to equitability in wealth distribution (through risk–reward sharing and access to finance) and economic stability are expected from IBSI (

Chapra 2008;

Ayub 2018); likewise, as envisioned by earlier writers, including Mawdoodi and Qutb, IBSI is expected to promote socioeconomic justice (

Maudoodi 1941;

Abdulrehman 2000). The social objectives include poverty reduction and ethical investing (

Asutay 2012); Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) (

Sairally 2007); the promotion of social values, including human rights and fair dealings (

Obaidullah 2005); and environmental protection (

Saged et al. 2017).

Perhaps it would be too optimistic to expect that all Islamic banks will uniformly achieve these objectives. Considering the conduciveness of the operating environment, these objectives may be achieved at different stages of organizational life.

Hanif and Farooqi (

2023) conceptualized the objectives as basic/primary, intermediate and advanced.

Primary Objectives include Shari’ah compliance (as well as local laws) and commercial performance.

Intermediate Objectives include adopting financial products that promote equity in wealth distribution and economic stability.

Advanced Objectives: the final stage is the discharge of socioeconomic responsibilities. The CSR standard issued by

AAOIFI (

2015) classifies CSR activities as mandatory (customer screening, responsible dealings, policy for prohibited earnings and expenditures, employees’ welfare, and

Zakah) and recommended (

qarḍ e hasan, environmental protection, social impact investment quotas, excellence in customer service, SME savings and investments, and

waqf management). Many of these responsibilities are voluntary or recommended based on Islamic values. For example, extending

qarḍ e hasan, investing in welfare projects,

waqf management, etc., are voluntary acts and grouped under

Ihsan (benevolence) (

AAOIFI 2015).

UAE IBSI is selected for examination of progress in achieving Islamic finance objectives. Quarterly data for eight years of financial reports (2013–21) was extracted from the database of the Islamic Financial Services Board (

IFSB 2022). The sample data covers 33 quarters (2013 Q4 to 2021 Q4)—a relatively recent period. Findings are reported based on the balance sheet analysis.

Figure 2 depicts the analytical framework. Considering objectives, the study focuses on sources and uses of funds. Sources of funds include equity, deposits and other liabilities (including inter-banking liabilities and other liabilities). The deposit structure was examined in detail, with a focus on the application of the risk–reward sharing principle. Funds utilization by IBSI is another aspect of the study. The classification encompasses investments in Shari’ah-compliant securities, Shari’ah-compliant financing, and other assets (including interbank financing). A special focus has remained on the application of financing modes in extending credits, considering the specific objectives of IBSI, including financial stability and equitable wealth distribution. Data trends are depicted through graphs to strengthen the findings. Growth is calculated by the following equation:

denotes the closing value, is the value at the beginning, and n is the number of quarters.

Commercial performance is measured in five key areas, including the Capital Adequacy Ratio (CAR), Non-Performing Finance (NPF), Return on Equity (ROE), Cost-to-Income Ratio (CIR), and Liquid Asset Ratio (LAR). CAR is measured as total regulatory capital divided by risk-weighted assets (total regulatory capital/risk-weighted assets). NPF ratio is measured as gross non-performing finance divided by total financing. ROE is calculated as net income divided by equity. LAR is calculated by dividing liquid assets by total assets. CIR is calculated as operating costs/gross income. The research is limited to the evaluation of two aspects of IBSI: financial performance and economic objectives.

4. Analysis & Findings

United Arab Emirates: The UAE market pioneered modern Islamic commercial banking with the establishment of the Dubai Islamic Bank in 1975. The UAE ranked 10th in the IFSB Report 2023 based on the percentage share of Islamic banking in total domestic banking assets within the country. The UAE IBSI market has achieved domestic systemic importance, along with 14 other IBSI markets. The volume of Islamic banking assets in the UAE surpassed USD 240 billion by 2022, accounting for approximately 11% of the global Islamic banking industry’s assets under management. The UAE is ranked 4th based on its contribution to global Islamic banking assets, following Saudi Arabia, Iran, and Malaysia (

IFSBr 2023). By the end of 2021 Q4, the UAE had 10 Islamic banks with a branch network of 212, employing more than 7000 professionals (

IFSB 2022).

As the conceptual framework suggests, the findings are documented in two sections: macro (encompassing broader economic objectives) and micro (focusing on commercial performance).

Economic Objectives: The economic objectives of IFSI include achieving financial stability and promoting an equitable distribution of wealth. Financial stability is expected to be achieved by linking real and financial sectors; specifically, an increase in debts is linked with an increase in actual economic activity, while equitability in wealth distribution is expected to improve by the application of profit and loss-sharing contracts based on the actual outcome of an activity, as well as access to finance, especially underserved/unserved masses (

Chapra 2008). The achievements of the UAE IBSI in the areas of economic objectives are documented through the application of balance sheet analysis (

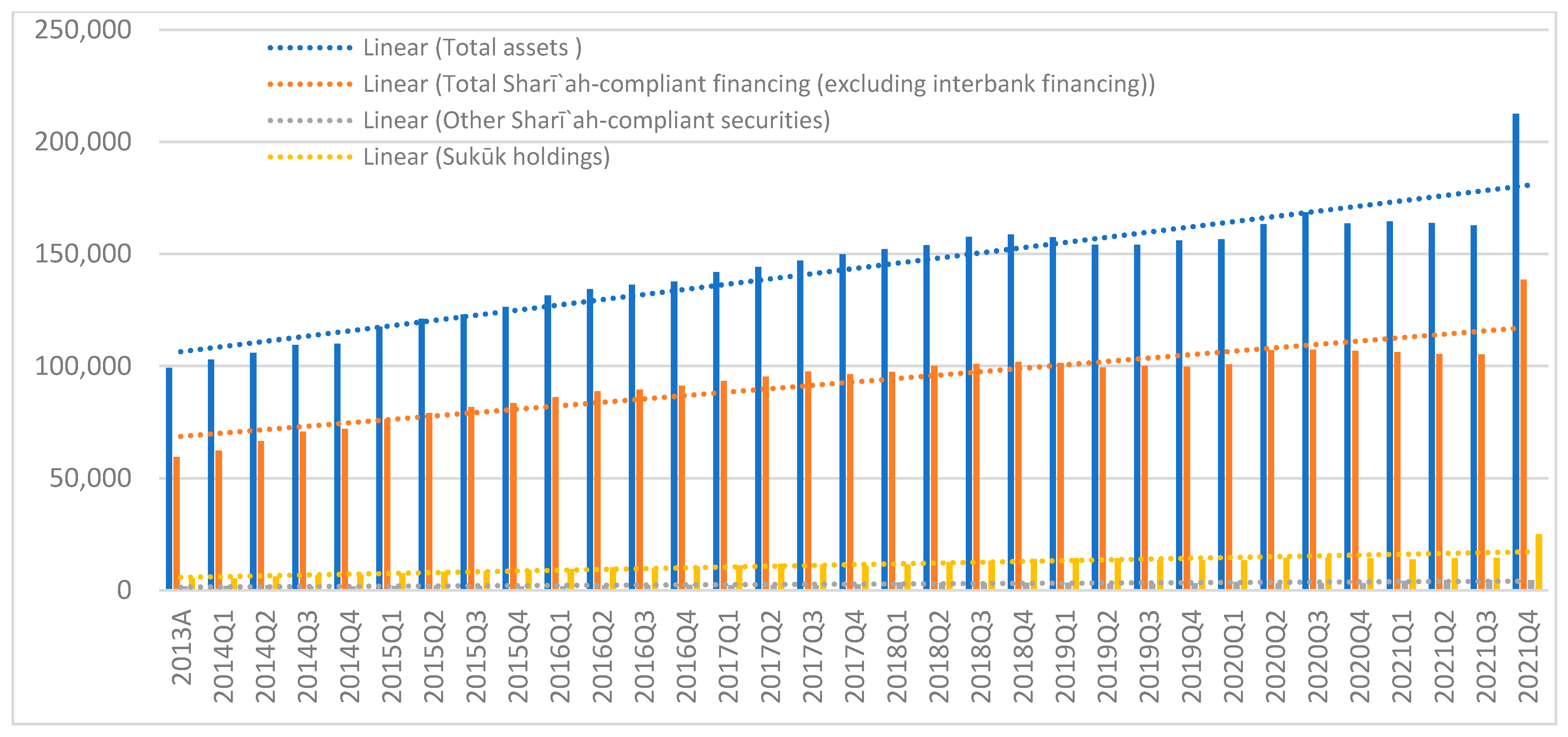

Figure 3). Data for Conventional Banking with Islamic Windows (CBIWs) is reported for the last quarter only, while it is available for the whole review period for Islamic Banking Institutions (IBIs). Islamic banking assets in the UAE have grown from USD 99.13 billion (2013 Q4) to USD 212.46 billion (2021 Q4) [

Figure 3], depicting a growth rate of 2.41% per quarter (see Methodology section) during the review period. The growth rate was 1.52%, excluding CBIW data. A significant increase in assets in the last quarter is due to the inclusion of CBIW data.

The summary statistics of the UAE IBSI asset structure are presented in

Table 1.

Figure 4 presents the growth trends of UAE IBSI. By the end of 2021, Total Shari’ah Compliant Financing (TSCF) accounted for a healthy 65% of total assets. The average quarterly percentage is 64.7%, ranging from 60.0% (Q4 2013) to 66.4% (Q3 2017). Based on quarterly percentages (TSCF/TA), the trendline indicates a slight upward movement—an indication of the increase in the share of TSCF from 2014 to 2021.

Sukuk holdings of the UAE IBSI are 11.8% of total assets (as of 2021 Q4). The quarterly average is 7.8%, with a range of 5.2% (2014 Q1) to 11.8% (2021 Q4), indicating significant variations. The trendline based on quarterly percentages shows upward movement—an indication of the increase in the share of

sukuk investments over the period. Investment in Other Shari’ah Compliant Securities (OSCS) accounts for 2.18% of total assets as of 2021 Q4. The quarterly average is 1.9%, ranging from 1.4% (Q4 2015) to 2.8% (Q3 2021). The trend line based on quarterly percentages shows upward movement, indicating an increase in the share of OSCS during the review period. Average results for the sample period are not much different after excluding CBIW data: the results are TSCF (64.7%),

sukuk holdings (7.7%), and OSCS (1.9%). As of 2021 Q4, interbank financing accounts for 3.4% of total assets. Approximately 79% of the asset portfolio consists of TSCF,

sukuk holdings, and OSCS. A higher percentage of TSCF signals achievements in the areas of retail financing and trade and commerce financing, as opposed to passive investments (e.g.,

sukuk holdings). Results for the Pakistani market as documented by

Hanif and Farooqi (

2023) shows TSCF of 46.9%,

sukuk holdings of 22.5%, and OSCS of 3.9%. A comparison indicates that UAE IBSI utilized more funds in the actively managed section (TSCF) of the portfolio than in passive investments.

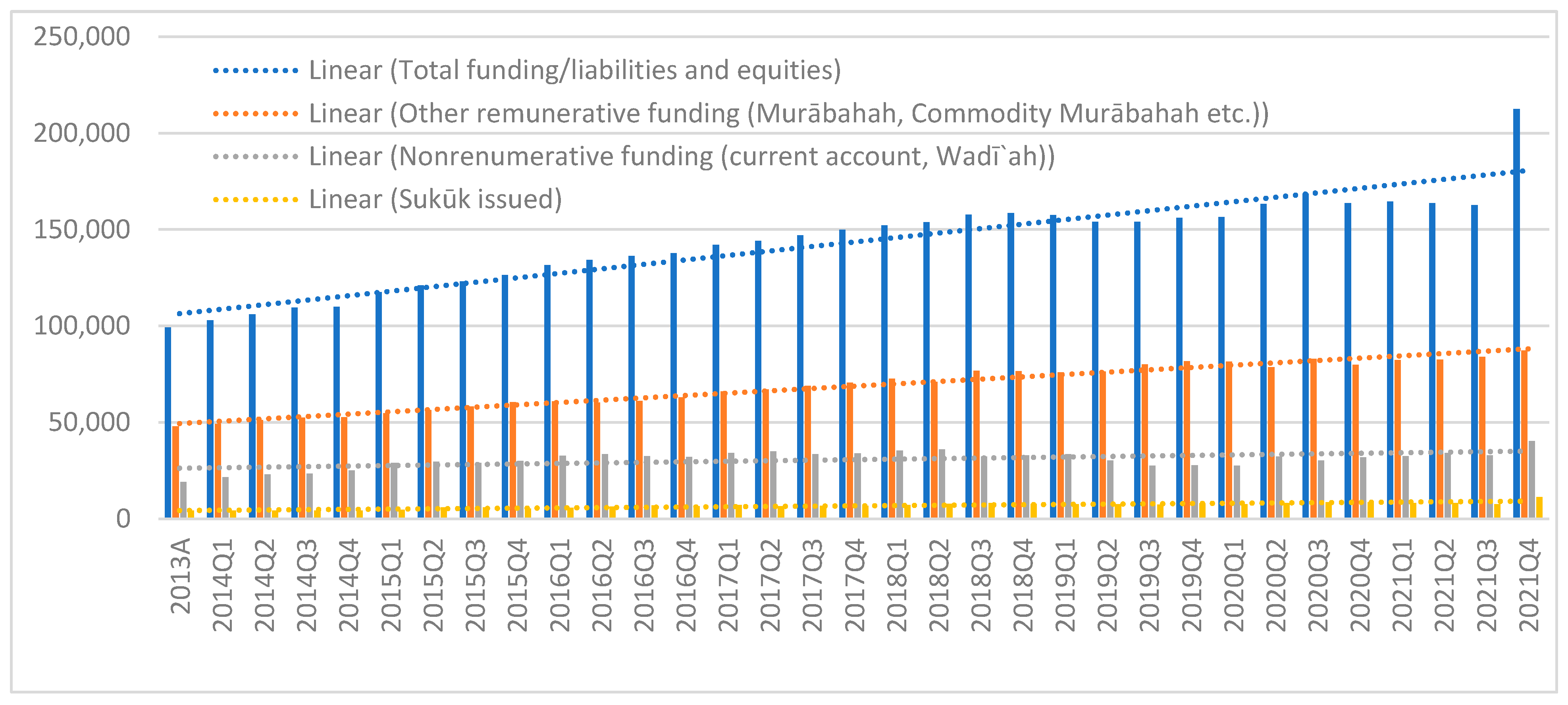

Summary statistics for the supply of funds are reported in

Table 2. By the end of 2021, on the supply side of funds, 66.3% of funds are generated by deposits, including the Profit and Loss Sharing Investment Account (PSIA) (6.3%), Other Remunerative Funding (ORF) (41%), Nonremunerative Funding (NRF) (19%),

sukuk issued (5.2%), equity (11.8%), and the rest are other liabilities including interbank funding. PSIA data is reported for the last quarter only.

As of 2021 Q4, significant deposit funding is remunerative (71.4%). ORF (including

Murabaha, Commodity

Murabaha, etc.) dominates in the deposit collection, with a 61.9% share in deposits, followed by NRF (current account,

Wadi’ah) at 28.6% and PSIA at 9.5%. In the case of ORF, the sample period average is 69%, while the same is 31% for NRF. ORF ranges between 64% (Q2 2016) and 75% (Q1 2020). The trend line based on quarterly percentages shows an upward movement—an indication of the increase in ORF share during the review period. The NRF ranges between 36% (2016 Q2) and 25% (2020 Q1), with a downward trend based on quarterly percentages from 2013 Q4 to 2021 Q4. The sample average of collection through

sukuk as a percentage of total funding is 4.6%, with a range of 3.77% (Q4 2014) to 5.2% (Q4 2021). The trendline based on quarterly percentages shows a slightly upward movement.

Figure 5 depicts trends in the supply of funds for UAE IBSI. The average results are not significantly different when excluding the last quarter from the calculation. Results for the Pakistani market as documented by

Hanif and Farooqi (

2023) shows PSIA (48.9%), NRF (26.6%), and ORF (6.1%). A comparison indicates that Pakistani IBSI utilized more PSIA in the collection of funds.

These figures lead to significant policy implications. In the United Arab Emirates IBSI, a pioneer economy in adopting Islamic banking in the 1970s, a serious effort is needed to promote profit and loss-sharing deposits—a hallmark of the Islamic financial system. A move in the right direction occurred in the last quarter (2021 Q4). Policy institutions (like central banking) may consider designing and enforcing a program to promote PSIA among Islamic banking institutions. The act would contribute to achieving the equitability of wealth distribution—an aspirational objective of the Islamic financial system.

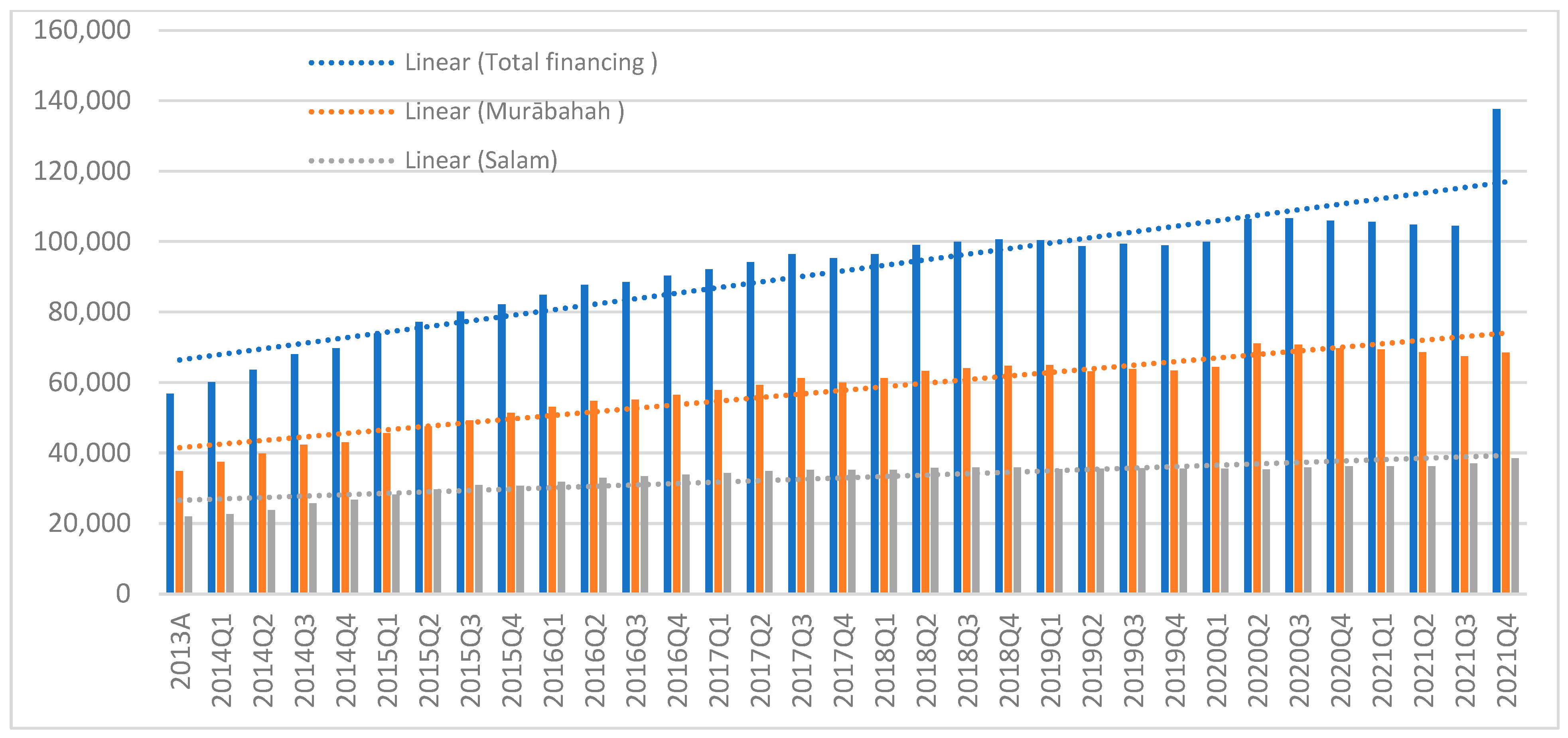

Descriptive statistics are presented in

Table 3, whereas

Figure 6 depicts the application of contracts in financing, including debt-based (

Murabaha,

Salam,

Istisna’a and

Ijarah) and equity-based (

Musharakah,

Mudarabah). Predominantly debt-based financing is observed. Except for the last quarter (2021 Q4), the major portion of funding was provided through

Murabaha (63.1%), followed by

Salam (36.3%) (sample period averages). Average results are not significantly different after excluding the last quarter from the calculations. However, the financing portfolio makeup was changed with the introduction of data for CBIWs in the last quarter. The financing portfolio make-up for the last quarter is

Murabaha (49.7%), Commodity

Murabaha/Tawarruq (11.8%),

Salam (28%),

Ijarah (6.7%),

Istisna’a (3%),

Wakalah (0.3%),

Murabaha (0.2%),

qarḍ e hasan (0.1%), and others (0.2%). The range of

Murabaha financing is 61% (Q4 2013) to 67% (Q2 2020), except for the last quarter. The trend line, based on quarterly percentages, shows a slight upward movement. However, in the case of

Salam financing, the range is between 39% (2015 Q3) and 33% (2020 Q2), except for the last quarter, with a downward trend line based on quarterly percentages. Results for the Pakistani market as documented by

Hanif and Farooqi (

2023) show profit and loss sharing (53.1%) and asset-based financing (28.0%). A comparison indicates that Pakistani IBSI more often utilized the profit and loss-sharing mode of financing in extension of credit.

Murabaha has more similarities than differences with conventional loans and is easy to execute; hence, it is the preferred choice of Islamic bankers globally. However, significant operations of an Islamic bank based on debt financing (

Murabaha,

Salam,

Istisna’a, and

Ijarah) will only contribute a little overall to the achievement of Islamic finance objectives. Debt-based financing is extended through assets (asset-based financing), leading to the achievement of an essential Islamic finance objective of financial stability (linkage of real and financial sectors). However, UAE IBSI needs to pay more attention to applying equity financing tools, including

Musharakah and

Mudarabah. While the linking of the real economy with the paper economy (asset-based loans) is appreciable in itself, and aimed at reduction in financial instability, the lack of (lesser) application of equity-based financing tools is not appreciable on account of failure in establishing equitability in wealth distribution (

Chapra 2008). Furthermore,

qarḍ e hasan, a tiny 0.1% (USD 81 million) of total financing in the last quarter, is appreciable but insufficient, indicating a lesser focus on the area of social objectives of Islamic finance. Nonremunerative deposits, with zero returns to depositors, are close to 31% of total deposits during the review period. The utilization of approximately 50% of average checking accounts for the extension of

qarḍ e hasan may not be an unbearable burden for IBSI. Such charity loans, aimed at social uplift, will contribute to the achievement of the social objectives of IFSI and bring benefits to humanity as a whole. For example, financing the educational expenses of students from low-income families through charitable loans is expected to yield manifold benefits to society.

Based on the evidence, it can be concluded that IBSI in the UAE has made partial progress toward achieving its broader economic objectives. While the application of asset-based contracts enhances contributions to financial stability, the lack of application of equity-based contracts (profit and loss sharing) in deposit collection and provision of financing indicates a failure to achieve the cherished goal of equitability in wealth distribution. It is encouraging to note that in the last quarter (2021 Q4), progress has been made through the introduction of PSIA in deposit collection and Mudarabah-based financing, as well as qarḍ e hasan in the financing portfolio.

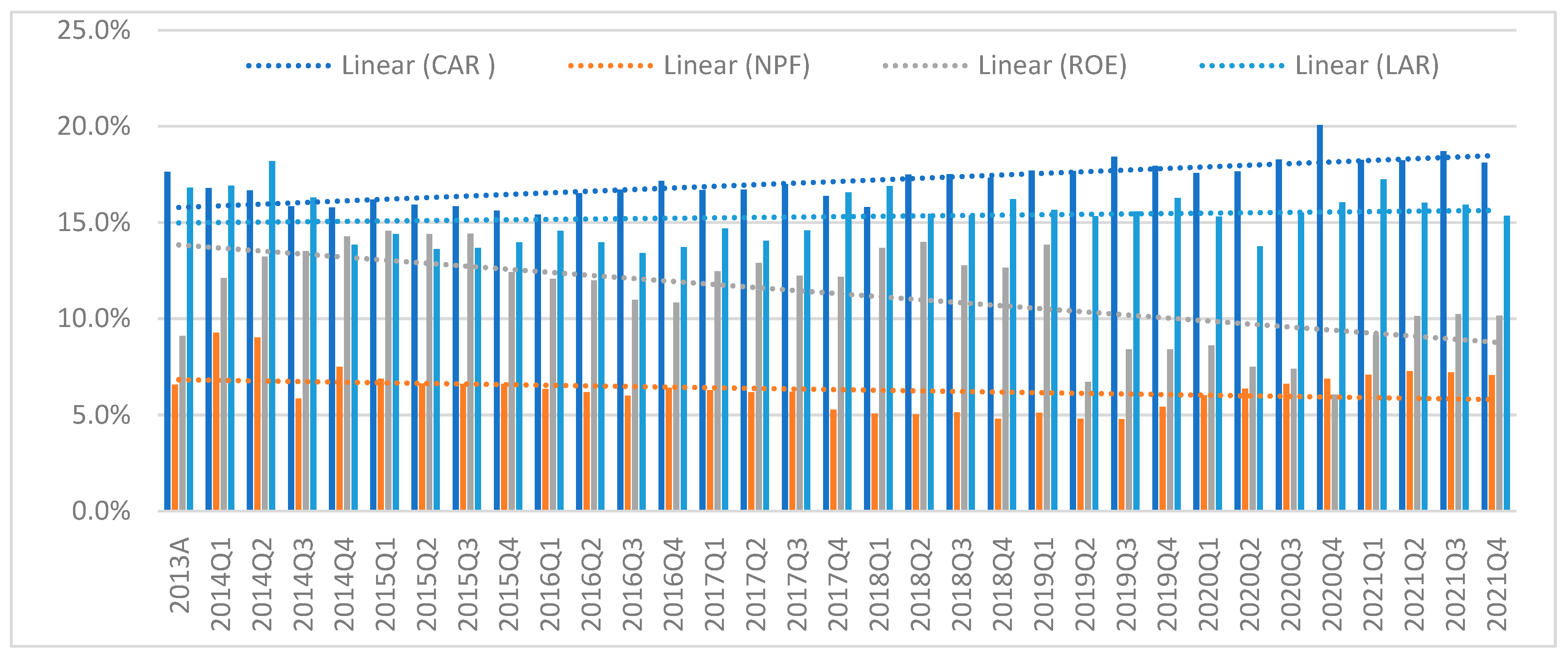

Micro Objectives: these objectives include Shari’ah compliance and being profitable. The survival of an Islamic bank within Shari’ah constraints is grouped under micro-objectives. Descriptive statistics are reported in

Table 4, whereas

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 present the results for UAE IBSI during the review period. CBIW data is available for the last quarter only within the selected database; average results are not significantly different after excluding the last quarter from the calculation.

CAR (capital adequacy) is an essential financial ratio to judge the capital sufficiency of a bank, which is required to pass stress testing. Basell-3 specifies a minimum requirement of 8.0% (

Basel 2019). The average CAR based on quarterly percentages is 17.1%, with a standard deviation of 1.1%. CAR ranges between 15.4% (2016 Q1) and 20.1% (2020 Q4), with an upward trend line. The average CAR is more than double the Basel requirement (of 8.0%), and not less than 15.4% for any of the 33 quarters under review, indicating the financial strength of IBSI in the UAE.

NPFs (non-performing loans) measure credit risk and the company’s efficiency in collecting receivables. A lower NPF is an indication of low credit risk and vice versa. Average NPFs are 6.3% with a standard deviation of 1.1%, an indication of variation; the range is between 9.3% (2014 Q2) and 4.8% (2019 Q3) with a slightly decreasing slope of the trend line during the review period (

Figure 7). Higher average NPFs in UAE IBSI are a cause for concern and require the attention of industry leaders.

ROE (return on equity) is a significant measure of profitability and net returns as a percentage of capital the business generates for its owners. The average ROE is 11.3%, with a standard deviation of 2.5%, indicating higher variations. During the review period, the range is between 14.6% (2015 Q1) and 6.1% (2020 Q4), with a significant downward slope of the trend line. One likely reason is COVID-19 restrictions, because ROE is less than 10% in the eight quarters from 2019 Q2 to 2021 Q1. UAE IBSI has performed well in terms of survival goals, achieving a positive ROE in double digits, except for 2013 and the period from 2019 Q2 to 2021 Q1.

The LAR (liquid asset ratio) aims to measure a banking institution’s ability to meet its obligations as and when due. The average LAR for UAE IBSI is 15.3% with a standard deviation of 1.2% (lower variations), ranging between 13.4% (2016 Q3) and 18.2% (2014 Q2) with a moderate upward movement of the trend line during the review period. Prudent management of LAR is essential, as a higher LAR enhances short-term solvency but negatively affects profitability.

Finally, the CIR (cost-to-income ratio) is calculated to measure operating efficiency. A low CIR contributes positively to the generation of a healthy ROE and the efficient operation of the organization. The average CIR is 50.7% with a standard deviation of 2.5% (low variation), ranging between 54.7% (2013) and 44.6% (2021 Q3), with a moderate decrease in the trend line during the review period (

Figure 8). CIR improved in 2014 and 2015, then rose and reached 53.5% in 2019. Another improvement occurred from 2020 onward and closed at 45.3% in the last quarter of the review period.

Evidence suggests improvement in the commercial performance of IBSI in the UAE. Capital adequacy is healthy and moving upward, nonperforming finance (although high) is going down moderately, liquidity is kept close to 15% with a slight upward movement, cost to income is close to 50% with a moderate decreasing trend, while ROE is in double digits except for eight quarters and in 2013, albeit with a decreasing trend. Management of NPFs and ROE could be a cause of concern for managers of IBSI in the UAE.

5. Conclusions

The study documents the achievements of IBSI in the areas of economic objectives and commercial performance in the leading market of the UAE using quarterly published financial data for 2013–2021. Results are documented by focusing on the application of suggested contracts to achieve specific Islamic finance objectives, including financial stability and equitable distribution of wealth. In addition, the commercial performance of the IBSI is also reviewed and documented.

An encouraging picture of the industry emerges based on achievements in the area of commercial performance and financial stability. Multiple asset-based financial contracts, including deferred sales (Murabaha, Tawarruq), forward sales (Salam and Istisna’a), and leasing (Ijarah), are utilized by the UAE-IBSI, aimed at contributing towards the linkage of real and financial sectors, resulting in the achievement of financial stability. Likewise, IBSI has displayed profitability, liquidity, solvency, and cost control during the review period. However, the application of contracts aimed at contribution towards equitability of wealth distribution remained a less-focused area during the review period. IBSI has yet to demonstrate significant interest in applying profit and loss-sharing contracts, although a beginning was made in 2021 with the introduction of PSIA. IBSI may consider financing mortgages by the application of diminishing Musharakah contracts.

These findings are expected to enrich the knowledge of the Islamic financial system, with a focus on objective industry evaluation among both academics and practitioners. The UAE IBSI offers lucrative

halal investment opportunities because the market share is close to 23% (

IFSBr 2023). Policy implications include a suggestion for Islamic bankers to consider the application of profit and loss-sharing contracts, in addition to asset-based contracts, to achieve Islamic financial objectives. Additionally, they may consider allocation of a portion of current deposits for extending

qarḍ e hasan, specifically for financing educational expenses for students from low-income families. Additionally, regulatory institutions may consider adopting a model portfolio incorporating profit and loss-sharing financial contracts and establishing minimum limits for applying less-focused financial contracts. The proposed acts are expected to address the perception of ’how the Islamic financial system differs from the conventional’ by highlighting a visible difference. Visible differences in the process and the outcome are the raison d’être of establishing a religion-based financial system.

This study’s limitations include a lack of documentation of achievements in access to finance and contributions towards social uplift. Future studies are expected to document achievements in these areas and examine the quality of Shari’ah compliance in various IBSI markets, including the GCC region.