1. Introduction

Micro-, small-, and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) play a pivotal role as drivers of economic growth and innovation across various sectors. Despite their importance, MSMEs face dynamic challenges and high levels of uncertainty, which can significantly threaten their survival and success. The ability to identify, assess, and manage risks effectively is critical for maintaining continuity and competitiveness in an increasingly complex and unpredictable business environment. Risk management involves systematic identification, analysis, and appropriate response to threats and opportunities that may impact organisational objectives. While larger organisations often integrate risk management through dedicated teams and substantial resources, MSMEs face limitations in expertise, time, and capital. ISO 31000:2018 provides guidelines, principles, and frameworks adaptable to different enterprises, sectors, and types of risks throughout the organisational lifecycle, emphasising the importance of integrating risk management into decision-making processes at all organisational levels (

ISO 2018). Furthermore, in the context of the Western Balkans, empirical evidence indicates that MSMEs often experience constrained access to finance, high financing costs, and limited financial literacy, which amplifies their vulnerability and underscores the necessity of precise risk assessment (

European Investment Bank [EIB] 2016;

Ahmeti and Fetai 2021). Recent prospective analyses of MSMEs in the Western Balkan (6) countries highlight that both financial and non-financial obstacles continue to restrict enterprise growth, with the most effective support stemming from tailored financial instruments, equity participation, guarantees, and advisory services (

Atanasijević et al. 2021).

In Montenegro, the classification of MSMEs is based on clearly defined economic criteria established by the Institute for Standardization of Montenegro (

Institute for Standardization of Montenegro [ISM] 2025), in accordance with European practice and European Commission Recommendation 2003/361/EC (

European Commission [EU] 2003). This categorisation relies on three main indicators: number of employees, annual turnover, and total asset value. According to current standards, micro-enterprises have up to 10 employees, an annual turnover of up to EUR 700,000, and assets not exceeding EUR 350,000. Small enterprises employ between 10 and 50 people, with an annual turnover from EUR 700,000 to EUR 8,000,000 and assets between EUR 350,000 and EUR 4,000,000. Medium-sized enterprises employ between 50 and 250 people, generate an annual turnover between EUR 8,000,000 and EUR 40,000,000, and have assets valued between EUR 4,000,000 and EUR 20,000,000. This classification forms the basis for differentiated economic policies, access to financial incentives and credit lines, and serves as a framework for monitoring the competitiveness and sustainability of the entrepreneurial sector in Montenegro.

The application of advanced methods, including scenario analysis, SWOT analysis, historical data evaluation, and particularly machine learning (ML) techniques such as artificial neural networks (ANNs), enables MSMEs to gain a comprehensive understanding of potential risks.

This approach facilitates the identification of critical threats that may seriously affect business performance and long-term development. The objective of this study is to apply artificial intelligence (AI), with a focus on NNs, for risk assessment, classification, prediction, and mitigation, providing MSMEs with valuable insights to select optimal strategies in line with their capacities and business priorities.

Effective risk management requires not only the formalisation of processes and procedures but also the development of a risk-aware organisational culture that fosters proactive thinking among employees and key stakeholders, thereby enhancing overall organisational resilience.

Given the dynamic nature of risks, continuous monitoring, evaluation, and prediction are essential for sustaining stable operations.

As a case study, this research analyses data from 2478 MSMEs in Montenegro, aiming to apply ML tools within an AI framework to develop a tailored methodology for assessing, classifying, predicting, and mitigating risks effectively.

This approach enables proactive responses to potential threats and ensures the long-term survival and sustainable success of enterprises.

The first section of this paper reviews the relevant literature focusing on the application of NNs and other AI methods for risk assessment and management in MSMEs. This literature review identifies existing approaches and their advantages and limitations and provides a foundation for developing the methodological framework of this study. The second section details the dataset, methodological approach, and applied metrics, while the third section presents the research results. The fourth section discusses and interprets the findings, and the conclusion summarises this study’s limitations, practical implications, and recommendations for future research.

1.1. Application of NNs in Financial Modelling of MSMEs

Neural networks (NNs) are a core methodology in AI, and they are particularly well suited to assessing and classifying financial risks in MSMEs. These computational models are inspired by the structure and function of the human brain, consisting of interconnected processing units—neurons—that process information through adaptive learning procedures. In the context of MSMEs, NNs can identify complex patterns and interdependencies within financial and operational datasets, enabling accurate detection of firms at elevated risk of financial instability or insolvency. Their ability to model nonlinear and multidimensional relationships makes them especially effective in risk analysis for enterprises, where conventional statistical approaches often struggle to process the full range of relevant variables efficiently.

The use of NNs in MSMEs supports the predictive analysis of key financial indicators, including turnover, profitability, workforce size, and operational costs, while also allowing integration with categorical variables such as enterprise type and banking status.

Employing NNs enables detailed risk mapping, identification of vulnerable enterprises, and provision of empirically grounded recommendations for strategic decision-making.

Successful implementation of NNs requires careful data collection and preprocessing, selection of an appropriate network architecture, and optimisation of hyperparameters. Challenges such as overfitting, particularly common in small datasets, are addressed using techniques such as regularisation, cross-validation, and parameter tuning. Overall, the application of NNs in MSMEs enhances early warning systems, optimises financial decision-making, and strengthens enterprise resilience, thus contributing to sectoral sustainability and long-term development.

NNs are widely used in the literature to predict the profitability, growth, and financial stability of MSMEs. Models developed for estimating small and medium enterprise (SME) profits demonstrate the superiority of NN-based approaches over traditional statistical methods due to their ability to recognise nonlinear relationships in financial data (

Batra and Chauhan 2025). Similarly, NNs have been applied to predict the growth of micro and small enterprises, highlighting their effectiveness in identifying factors directly influencing business development (

Garcia Vidal et al. 2017).

The use of NN ensembles has been demonstrated for evaluating the economic conditions of SMEs, showing that combining multiple models enhances predictive accuracy and reduces classification errors (

Burda et al. 2007). The integration of AI into business functions further enables improved real-time decision-making and process optimisation (

Le Dinh et al. 2025), while deep learning (DL) algorithms are applied to SME management models to capture complex data patterns and support long-term risk forecasting (

Wang 2021).

NNs have also been used to anticipate business crises within MSMEs in the Arab region, demonstrating their ability to identify financially unstable enterprises early, thereby enabling timely intervention (

Rao 2018). Analyses of SME profitability using neural models confirm that NNs provide precise identification of critical financial variables influencing firm performance (

Nastac et al. 2017).

1.2. Credit Risk Prediction and Analysis

Credit risk assessment is a critical area for the application of NNs in MSMEs. A genetic backpropagation (BP) NN model has been implemented for credit risk evaluation, demonstrating the algorithm’s ability to integrate multiple data sources and reduce classification errors for credit-risky firms (

Chen et al. 2024). Incorporating soft information into neural models has been shown to enhance SME credit scoring systems (

Li et al. 2021), while BP NNs have been used for precise risk classification and to support strategic planning (

Li et al. 2022).

Fuzzy neural networks (FNNs) have been used for credit risk assessment, effectively addressing uncertainty and imprecision in SME financial datasets (

Gong 2017). In addition, relational graph attention networks have been applied to credit risk prediction, leveraging enterprise connectivity data to improve model accuracy (

Wang et al. 2024). These approaches highlight the growing trend of integrating advanced NNs into creditworthiness evaluation and risk assessment for micro and small enterprises.

1.3. Prediction of MSME Growth, Sustainability, and Performance

Predicting MSME growth often involves evaluating key factors such as innovation, strategic flexibility, and organisational agility. NNs have been shown to facilitate the analysis of the effects of innovation and strategic flexibility on sustainable MSME growth (

Arsawan et al. 2022;

Todri et al. 2020). Neural models have also been applied to identify value drivers in rural business contexts, highlighting regional and market-specific characteristics (

Vrbka 2020).

Self-Organising Maps (SOMs) have been used to assess post-pandemic MSME performance, demonstrating that NNs enable the visualisation of trends and the identification of the most vulnerable enterprises (

Martinez et al. 2023). Comparative analyses of NNs and linear regression algorithms in sales prediction confirm the superior performance of neural models in capturing nonlinear data patterns (

Taufiqih and Ambarwati 2024).

The development of innovation platforms for SMEs based on social perception and NN algorithms further demonstrates the potential of integrating AI into digital services and innovation processes.

1.4. AI Implementation and Challenges in SMEs

The adoption of AI technologies in SMEs faces several challenges, including technical constraints, employee competencies, and alignment with organisational needs. Implementing AI requires adapting business processes and evaluating employee competencies in line with strategic objectives (

Oldemeyer et al. 2024;

Vezeteu and Năstac 2024).

Structural Equation Modelling (SEM)–NN analyses have been used to assess the impact of AI technologies on sustainable SME performance, confirming that NNs enhance operational efficiency and competitiveness (

Soomro et al. 2025). Analyses of technological readiness in women-led SMEs show that NNs can identify factors influencing technology adoption and predict enterprise readiness for digital transformation (

Silitonga et al. 2025).

Studies on the current state of AI adoption in SMEs reveal varying acceptance levels, with significant differences depending on available resources and sector, highlighting the need for tailored implementation strategies (

Schwaeke et al. 2024). Factors facilitating or hindering AI adoption in MSMEs have been identified, particularly in the context of sustainable business practices (

Jamal et al. 2025).

Reports on AI implementation trends and challenges emphasise that resource and expertise constraints are especially pronounced in micro- and small enterprises (MSEs), necessitating strategic planning for effective adoption (

Spallone and Bandiera 2024;

Bianchini and Michalkova 2019).

1.5. Systematic Reviews and Research Trends

Continuous growth in AI and NN applications within MSMEs has been documented, particularly in predicting financial risks, growth, and strategic decision-making (

Pamungkas et al. 2023;

Oldemeyer et al. 2024;

Fajarika et al. 2024). The importance of DL algorithms and the integration of economic, technological, and organisational factors into neural models has been highlighted as a means to improve prediction accuracy and practical relevance in business environments (

Wang 2021;

Padilla-Ospina et al. 2021).

Unlike previous studies, this research introduces a comprehensive, empirically grounded framework for classifying financial risk and growth factors in MSMEs using advanced NNs. Earlier work has mainly focused on specific aspects such as credit scoring, profitability, or individual growth indicators (

Batra and Chauhan 2025;

Li et al. 2022), whereas this study integrates multi-dimensional business classification within a unified neural framework, addressing both risk and growth holistically.

The novelty of this work is demonstrated by a case study involving 2478 MSMEs from Montenegro, providing an extensive dataset for rigorous empirical validation and comparative analysis of the models in a regional context characterised by small, developing economies with shared structural challenges. The analysis employs two NN architectures—NNET (

NNET 2025) and Multi-Layer Perceptron (

MLP 2025)—with results presented comparatively, enabling both quantitative and qualitative evaluation of each model’s predictive accuracy, sensitivity, and robustness in classifying MSMEs according to financial risk and growth potential.

This methodology leverages heterogeneous data sources, including financial statements, organisational characteristics, and innovation-related variables, processed through advanced NN architectures and relational graph algorithms. This enables the precise identification of nonlinear relationships and latent patterns that conventional methods often fail to detect (

Wang et al. 2024). Additionally, the framework explicitly links the technical execution of neural models with organisational and human factors, bridging the gap between analytical complexity and practical AI implementation in MSMEs. By enabling the simultaneous classification of financial risk, operational performance, and growth potential, the approach provides an innovative foundation for informed strategic decision-making and sustainable enterprise development (

Oldemeyer et al. 2024;

Vezeteu and Năstac 2024).

Importantly, this study addresses the challenges faced by small economies in the Western Balkans, where MSMEs dominate the business landscape but often operate with limited resources and financial vulnerability. The large-scale, multi-dimensional dataset used in this study ensures robust model training and validation, enhancing the reliability and generalisability of the results. By integrating economic, organisational, and innovation dimensions, the approach provides a novel, practical tool for policymakers, credit institutions, and enterprise managers, supporting early warning systems, targeted interventions, and regional economic resilience:

size—Categorical variable defining the size of the MSME (micro, small, and medium) according to the official classification.

crew—Credit rating assigned to the enterprise, derived using the methodology of CompanyWall Business and Solvent Rating d.o.o. The variable is classified into categories A1–E3, each reflecting a specific level of risk and probability of insolvency. This variable does not represent the number of employees nor any aspect of the workforce structure; it exclusively reflects the financial and economic standing of the enterprise.

abank—Company status according to the Central Registry of the Central Bank of Montenegro (CBCG); values: “yes” (active) or “no” (blocked).

turn—Total annual turnover in EUR.

net—Net profit in EUR.

emp—Number of employees in the MSME.

ebit—Earnings before interest and taxes.

coste—Fuel and energy expenses.

mcoste—Transport and maintenance expenses.

A credit rating “crew” is a set of objectified and standardized data that covers the entire business activity of a company. It is determined based on a special methodology that includes a financial and economic analysis of the business activities of the past year.

According to CompanyWall Business (

CompanyWall 2025), the credit rating is based on a combination of static and dynamic assessments. The static rating is derived from an analysis of key financial performance and liquidity indicators reported in the annual statement, while the dynamic rating captures changes over time and reflects the company’s ability to adapt and develop in the future.

A dynamic rating represents a variable value that is determined by variable factors such as the following:

The time the subject has spent in the blockade;

The number and outcome of legal proceedings in which the subject is involved;

Tax and other debts;

Liquidity;

The ratio of income in the public and private sectors.

The credit rating enables faster, simpler, and more efficient decision-making when selecting a business partner, analysing competition, and assessing risks. It supports the qualitative analysis of the specifics of an individual MSME.

Solvent Rating d.o.o. Podgorica (

Solvent Rating 2025) has developed a model for MSME credit rating (

Table 1) based on European standards. It is supported by leading experts in the field, who have fully adapted the methodology to the needs of the Montenegrin market. The methodology considers publicly available data, the most important of which are as follows: the MSME’s financial transactions, indicators derived from the financial statements, the status of the MSME, data on foreclosures, and other data.

MSMEs are categorized into the mentioned classes and categories above based on seven indicators, whereby the extent to which each indicator influences the overall credit rating class is determined. Since the methodology is adapted to the Montenegrin market, each of the seven indicators has a different influence on the credit rating class of MSMEs, which makes the credit rating different from the others.

The indicators based on which the credit rating is calculated are as follows:

Current liquidity ratio (GLR—General Liquidity Ratio) is calculated using the formula Current assets/liabilities. Participation in the calculation of the MSME’s credit rating is 9%. The short-term solvency indicator shows the extent to which current assets cover current liabilities. This indicator does not allow an assessment of the solvency of MSMEs but shows the factors that can influence it. The value of the indicator decreases when current liabilities grow faster than current assets, which may affect the increase in insolvency risk in the future.

The debt ratio (DR) is calculated using the formula (Total liabilities—Capital)/Total assets. Participation in the overall rating is 15%. The indicator provides information on how high the proportion of debt-financed assets is. The lower the value of the indicator, the more securely the MSME is financed.

The Ratio of Long-Term Sources and Fixed Assets and Inventories (RLTSFAI) is calculated using the following formula: (Capital + Non-current liabilities)/(Fixed assets + Inventories + Non-current assets held for sale and discontinued operations). Participation in the overall assessment of the credit rating class is 9%. This coefficient corresponds to the ratio between long-term debt and long-term assets and has the function of verifying the potential security of creditors, taking into account inventories as a possible means of settling long-term debt.

The solvent coefficient (SC) is calculated using the following formula: (Net comprehensive income + Other operating expenses (depreciation, amortization, provisions, and other operating expenses))/Long-term provisions and long-term liabilities. Participation in the overall assessment of the credit rating class is 9%.

The mean time of completion (in days) is calculated using the formula 365 × (Trade receivables/Change in value of finished goods and work in progress + Change in value of finished goods and work in progress + Income from own work capitalized and merchandise + Other income from operating activities). Participation represents the overall assessment of the credit rating class: 15%. It takes a certain amount of time for the company’s receivables to become cash. The indicator is expressed by the average number of days it takes to collect receivables.

Corporate profit represents operating profit. Participation in the total credit rating is 19%. Profitability rating is interpreted as net income before the burden of income taxes and interest.

The information on previous MSME blockades relates to 365 days up to the date of the financial report. In addition to the total duration of the blockade, it includes the uninterrupted duration of the period during which the MSME did not have a blockade. The share of the total credit rating class is 24%. Payment behaviour shows the habits of MSMEs regarding the settlement of liabilities in the past, i.e., in the last 365 days. In line with its importance, the indicator has the most points that influence the credit rating class of MSMEs.

Table 2 shows the data grouped according to the degree of the estimated “risk” (dependent variable) and the size of the MSMEa.

The data, grouped according to the degree of estimated “risk” and the credit rating class (crew), are shown in

Table 3.

The

Table 4 shows the distribution of data grouped by the estimated level of risk and the status of MSMEs (active or blocked/abank), enabling a comparison of how enterprises are represented across different risk categories.

The minimum, maximum, mean, median, and standard deviation (SD) values for all independent numerical variables, grouped according to the dependent variable “

risk”, are presented in

Table 5,

Table 6,

Table 7,

Table 8,

Table 9 and

Table 10.

2. Materials and Methods

The methodological framework of this research is based on the application of advanced ML techniques implemented in the R programming language (

The R Project for Statistical Computing 2025), with the aim of modelling and classifying financial risks among MSMEs. The process was conducted in clearly defined stages to ensure the accuracy, reliability, and replicability of the results.

The dataset comprises ten variables: four categorical or factor variables—“risk” (dependent), “crew”, “abank”, and “size”—and six numerical independent variables: “turn”, “net”, “emp”, “ebit”, “mcoste”, and “coste”. To assess potential redundancy and interrelationships among the numerical variables, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was performed. PCA provides a robust framework for dimensionality reduction and exploratory data analysis, enabling the identification of underlying structures, visualisation of patterns, and selection of the most informative variables for subsequent classification using decision trees.

During preprocessing, data completeness and consistency were verified for each enterprise; no missing or inconsistent values were identified, so imputation was not required. PCA results indicated that the variance explained by the PCA did not justify the removal of any variables, as each contributed uniquely to the model’s explanatory power. Consequently, all original variables were retained, preserving information that is essential for model accuracy and reliability. This approach ensures methodologically sound, interpretable, and stable NN results. Given this study’s focus and scope, a more detailed discussion of PCA procedures has been omitted to maintain emphasis on the core methodological and interpretative aspects.

Phase 1—Data Preparation and Processing: The collected data underwent thorough cleaning and preprocessing, including the removal of missing and inconsistent values, standardisation of formats, and harmonisation of variable types. All numerical data were then normalised to eliminate the effects of differing measurement units and scales among variables. Normalisation is a crucial step in NN training, as it contributes to optimisation stability and prevents variables with larger numerical ranges from disproportionately influencing the final model weights.

All categorical variables retain original coding from the official registries (

CRPS (

2025), CBCG, and credit reporting systems), while the numerical variables in the model are not kept in their original scales. All numerical columns are normalised using the

Min–Max transformation defined in Equation (1), ensuring a consistent value range and improving the stability of NN training. Normalisation is applied consistently to the training, validation, and test datasets:

This method ensures that all variables share a comparable scale and have equal influence within the model. Simultaneously, categorical (textual) variables were transformed into dummy (binary) format, enabling their numerical representation within the network. This step was essential, as NNs can process only numerical inputs, and dummy encoding ensures that each category is represented as an independent dimension, thereby avoiding erroneous interpretations of ordinal relationships among categories.

Phase 2—Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis: After data pre-processing, a detailed descriptive analysis (summary statistics) was performed, presenting the fundamental statistical parameters of each attribute.

Inter-variable dependencies were then analysed using correlation techniques. Cramer’s V coefficient was applied to assess associations between categorical variables, quantifying the strength of relationships among nominal features.

The association between numerical and categorical variables was evaluated using the Eta coefficient, which captures nonlinear relationships between variables of differing types. All correlation relationships were visualised using heat maps, providing an intuitive graphical representation of the degree of association among attributes and the target outcome. Correlations among numerical variables were analysed using the Pearson correlation coefficient, which best measures linear relationships among continuous numerical values.

The target variable “risk” was defined as a multiclass categorical variable with five levels (A, B, C, D, and E), where class A represents the lowest and class E represents the highest financial risk. Based on the analysed relationships between attributes and the target variable, the input features for NNs modelling were defined.

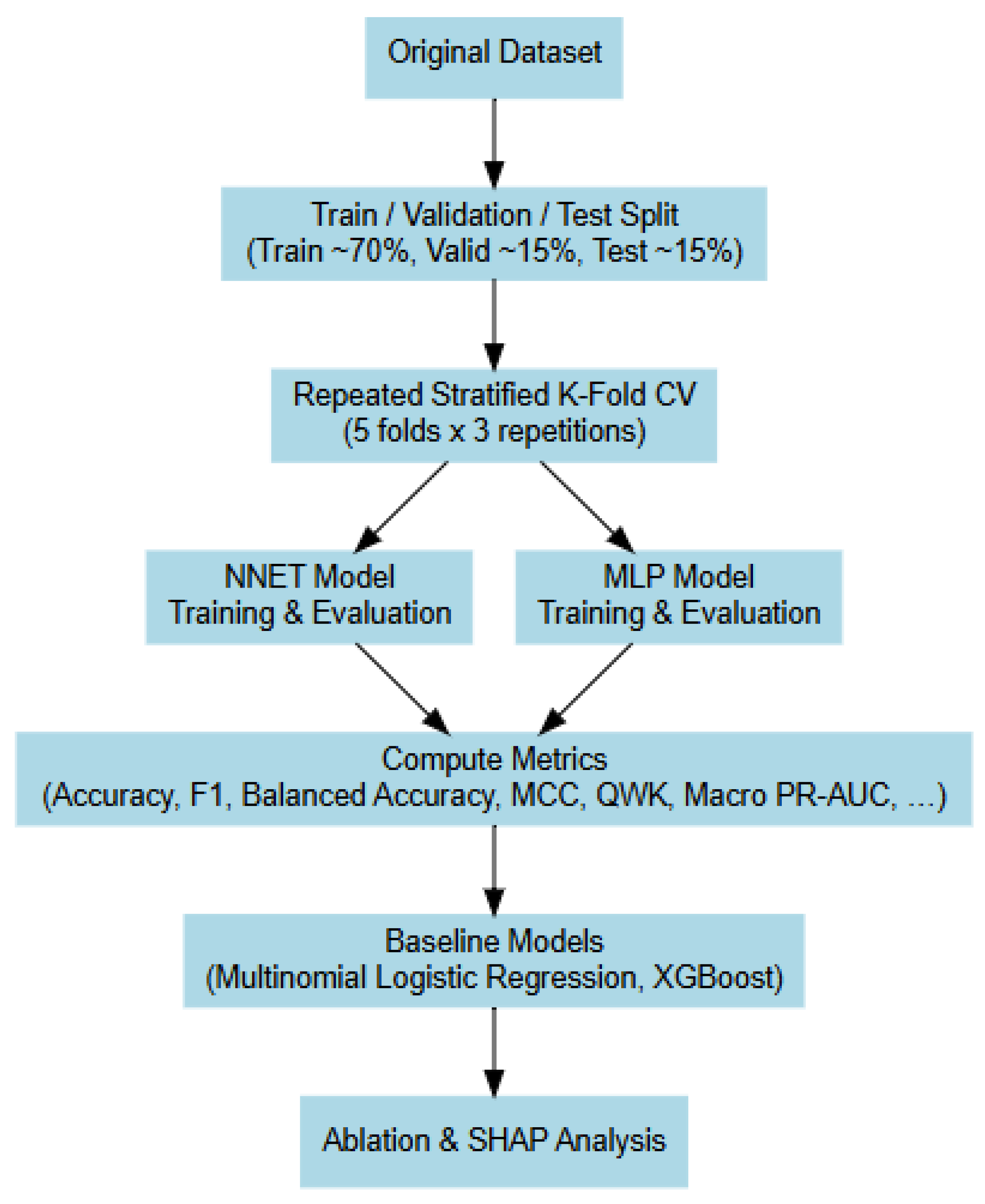

Phase 3—Neural Network Generation and Training: For modelling and classification, a robust approach was adopted using NNs. Specifically, two architectures were considered: “NNET” and “MLP”. Instead of a single fixed train–validation–test split, repeated stratified 5-fold cross-validation (three repetitions) was applied to better capture variance due to sampling and to provide uncertainty estimates for model performance. The input dataset was preprocessed, with the dummy encoding of categorical variables and min–max normalisation of numeric features. During training, multiple network configurations were tested, varying the number of hidden neurons (5, 6, and 7) and weight decay parameters (0.01 and 0.1), to identify the optimal balance between predictive accuracy and generalisation. For each fold, predictions were obtained on the corresponding validation set, and fold-wise performance metrics were computed. This procedure ensured that the selected model was robust to data partitioning and not dependent on a single arbitrary split.

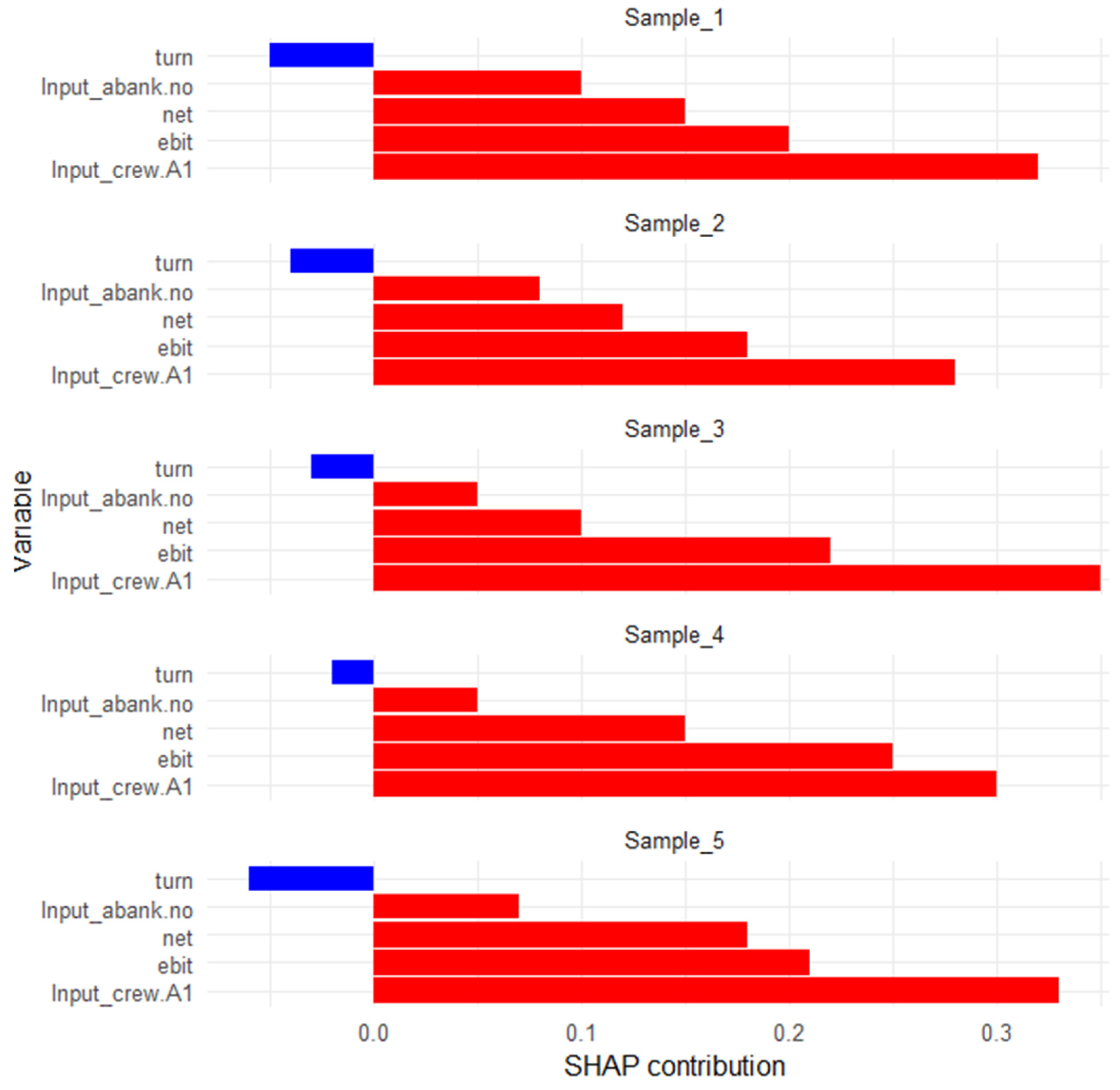

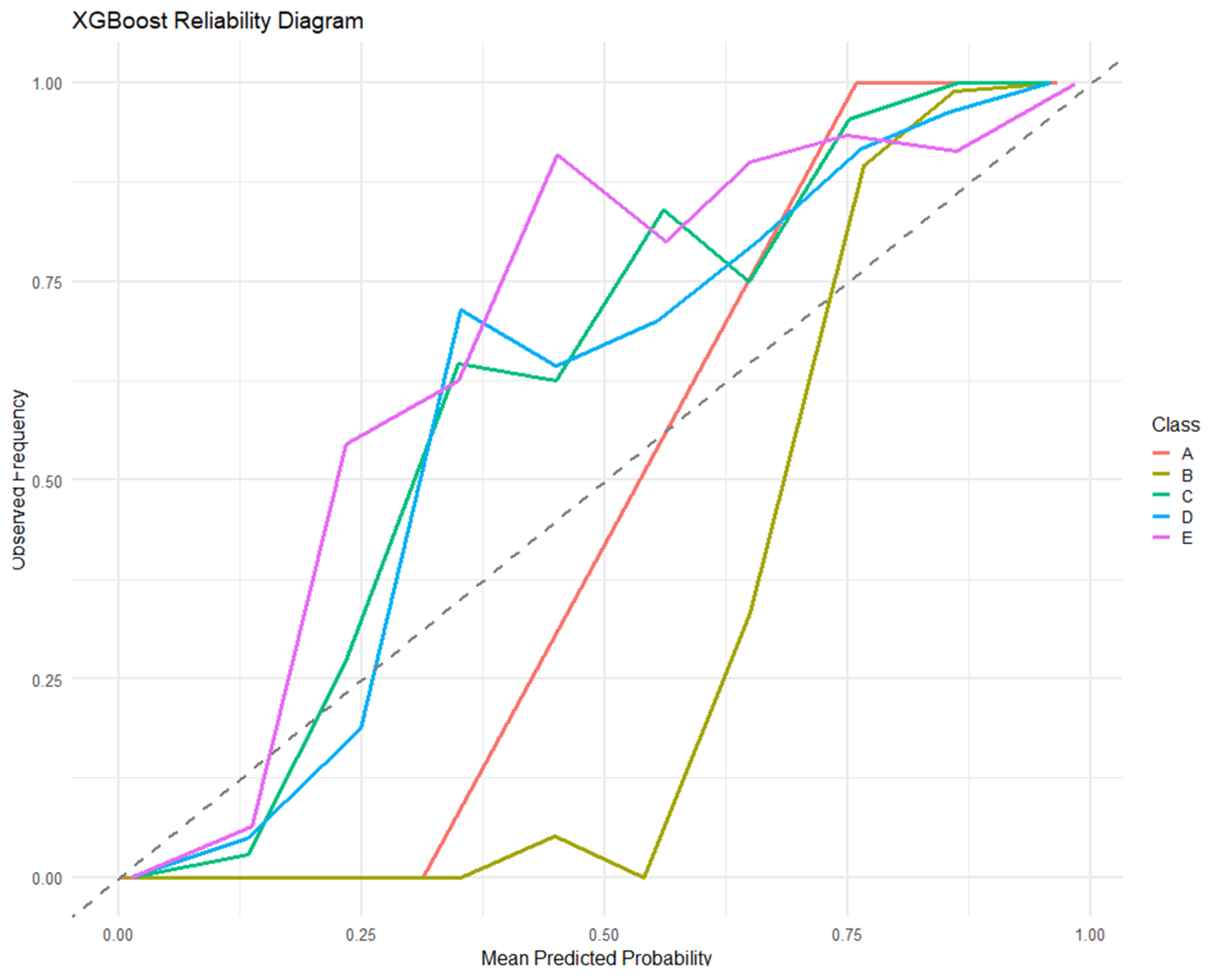

Phase 4—Model Evaluation and Result Analysis: In the evaluation phase, performance metrics were computed for each fold, including accuracy and the macro-F1 score. Fold-wise metrics were then aggregated to provide mean values with 95% confidence intervals, quantifying the uncertainty of the estimates. Confusion matrices were examined to understand misclassification patterns across risk classes. In addition to the NNs, two tabular baselines—regularised Multinomial Logistic Regression (MLR) and eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost)—were trained on the full dataset. For XGBoost, probability calibration and reliability analysis were performed, including Brier scores and reliability diagrams. Ablation analysis was conducted by removing the “crew” variable to confirm that model predictions were independent of potential information leakage. Finally, SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP)-based interpretability analysis was carried out for XGBoost, providing both global feature importance summaries and local explanations for representative instances. This comprehensive evaluation ensured a robust, interpretable, and reproducible assessment of model performance.

This approach enabled a comprehensive evaluation of predictive model quality. The importance of input variables for each model was visualised, identifying which features contributed most significantly to determining risk levels. NNs’ weight matrices and graphical representations were generated to illustrate the architecture and internal connections among model layers. Based on all metrics, confusion matrices, and visual analyses, the “NNET” and “MLP” models were compared to determine which achieved superior generalisation and stability in MSMEs’ financial risk classification. Furthermore, the execution time of both algorithms was analysed, as it is an important indicator of model efficiency and practical applicability. The comparative analysis of computational time enabled assessments of each approach’s computational complexity, contributing to a comprehensive evaluation of their operational value under real-world conditions.

During model training, neither the Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE) nor any form of oversampling or undersampling was applied, as the synthetic generation of minority class examples can distort the natural data structure and introduce unrealistic patterns, particularly in small and heterogeneous datasets. Instead, class weighting in the loss function, inversely proportional to class frequencies, was used to balance the contribution of each class without altering the true data distribution. This approach preserves the integrity of the original dataset, enhances training stability, and ensures that all evaluation metrics (BA, MCC, QWK, and Macro-PR-AUC) reliably reflect model performance on the natural class distribution.

To rigorously evaluate the performance of the “NNET” and “MLP” models, a repeated stratified k-fold cross-validation scheme (5 folds × 3 repetitions) was implemented. This robust framework quantifies performance variability arising from random sampling and yields reliable average metrics with confidence intervals. Data were partitioned into training, validation, and test sets while fully preserving the underlying class structure and distribution. The data-splitting logic and cross-validation workflow are summarised in a schematic diagram (

Figure 1).

Performance evaluation was conducted using metrics sensitive to class imbalance and ordinal relationships—precision, balanced accuracy (BA), Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC), quadratic weighted kappa (QWK), and Macro-PR-AUC—with all metrics computed from out-of-fold predictions generated during the repeated stratified 5 × 3 cross-validation.

For benchmarking, baseline models, including MLR and XGBoost, were implemented. An ablation study was also conducted by excluding the “crew” variable to assess its specific contribution to predictive performance. Model interpretability was enhanced using SHAP, providing both local and global feature contribution visualisations.

This methodology ensures transparency, reproducibility, and a rigorous assessment of model robustness and interpretability across multiple evaluation dimensions.

The methodological approach is shown in

Table 11.

Metrics

Correlation analysis was conducted using a threefold approach, tailored to the nature of the data and the types of relationships between variables. To assess associations among attributes, three complementary measures were employed: Cramér’s V (

Akoglu 2018;

Kuhn and Johnson 2013) for relationships between categorical variables, the Pearson correlation coefficient for relationships between numerical variables, and the Eta coefficient for evaluating links between numerical and categorical attributes. This combination provides comprehensive insight into the structure of interdependencies in the data, which is essential for preparing input variables and interpreting the results of classification models. To quantify the strength of association between nominal (categorical) variables, Cramér’s V coefficient (V) (

Brownlee 2020) (Equation (2)) was used. This is a standardised measure based on the χ

2 (chi-square) test of independence. Unlike the χ

2 test itself, which only indicates the presence of a statistically significant association between variables, Cramér’s V allows additional interpretation regarding the strength of the association, independently of the sample’s size (

Kearney 2017):

where

Cramér’s V values range from 0 to 1, where 0 indicates no association, and 1 indicates a perfect association between categories. Unlike the χ2 test, which only indicates whether an association exists, Cramér’s V quantifies the strength of the relationship, making it suitable for comparative analysis of multiple categorical pairs. In this study, it was used to examine relationships between discrete risk indicators, types of enterprises, business sectors, and other nominal attributes.

For relationships between two continuous (numerical) variables, the Pearson correlation coefficient (r) (Equation (3)) was applied. This measure quantifies the strength and direction of the linear association between two variables measured at interval levels. Pearson’s r values range from −1 to +1, where negative values indicate an inversely proportional relationship, positive values indicate a directly proportional relationship, and values near zero indicate the absence of linear correlation.

The Pearson coefficient is particularly suitable for analysing relationships among financial indicators that have been normalised, as linear links among them provide insight into the interdependence of key performance indicators (e.g., relationships between profit and costs, turnover, and liquidity). The reliable interpretation of the Pearson correlation requires the following assumptions: normality of distribution, linearity, homogeneity of variance, and absence of extreme values:

where

r denotes the Pearson correlation coefficient;

xi and yi denote individual values of the variables;

and denote the arithmetic means of variables x and y;

The numerator represents the covariance between the variables;

The denominator is the product of their standard deviations.

Alternatively, for precomputed statistical values, Pearson’s r can be expressed using Equation (4):

where the following are defined:

cov(

X,

Y)—covariance between variables

X and

Y;

σX and

σY—SD of variables

X and

Y.

The Eta coefficient (

η) (Equation (5)) (

Quantitative Methods in Public Administration 2025) is a statistical measure that quantifies the strength of a nonlinear relationship between a numerical and a categorical variable. Unlike Pearson’s coefficient, which measures only linear relationships between two continuous variables, Eta assesses the extent to which a categorical factor explains the variance of a numerical variable. Mathematically, Eta is calculated using ANOVA-based variance decomposition:

where

Eta values range from 0 to 1: Values near 0 indicate a very weak influence of the categorical variable on the numerical variable; that is, minimal differences between groups. Values near 1 indicate a strong association, meaning that the categorical factor explains most of the variance in the numerical variable.

In the context of ML and classification models, the Eta coefficient helps identify categorical variables with significant influence on numerical input features, assess the potential contribution of variables in predictive models, and detect variables with low predictive value that can be removed to reduce dimensionality and improve model efficiency.

The use of Eta is particularly valuable in datasets where numerical variables depend on discrete categories: for example, financial indicators divided by enterprise type, business sector, or risk level.

The visualisation of the correlation analysis results was performed using the R packages version 4.5.1 “ggcorrplot” and “corrplot”, which enable the display of correlation matrices for numerical variables, categorical variables, and combinations of numerical and categorical variables.

This approach allows quick identification of potential multicollinearity and supports the selection of relevant predictors for inclusion in machine learning models (

Oberg 2019).

This analysis served a dual purpose: (1) to provide a deeper understanding of the relationships among variables in the context of MSME risk classification and (2) to detect variables that potentially contribute to model redundancy, that is, variables that are excessively interrelated, which may increase model variance and reduce its ability to generalise to new data (

Brownlee 2020;

Kearney 2017).

A confusion matrix (

Table 12) is a fundamental analytical tool for evaluating the performance of classification models in ML and statistics. It is a square table that shows how many instances from the actual classes were correctly or incorrectly classified into the predicted classes. This matrix enables multidimensional analysis of the model, thereby avoiding reliance solely on a single indicator such as overall accuracy. In this study, the target variable was categorised into five risk groups reflecting different risk levels. For this multiclass problem, the confusion matrix was extended to a 5 × 5 dimension, with rows representing the actual classes and columns representing the predicted classes. Each cell of the matrix indicates how many examples truly belonged to a specific class and how many the model predicted into each of the five classes. This detailed matrix enables the identification of the classes for which the model performs best (high values along the diagonal) and detection of confusion between certain pairs of classes (high values off the diagonal), and it serves as a basis for calculating numerous model evaluation metrics such as sensitivity, precision, and others.

This detailed analysis is crucial for understanding model errors and identifying areas for potential improvement, which is particularly important in the context of MSME risk classification.

To prevent potential information leakage, an ablation analysis was conducted to compare model performance with and without the “crew” (credit rating) variable. The results confirmed that this predictor improves predictive accuracy without incorporating information from the target variable.

All data preprocessing steps—including normalisation of numeric features, categorical encoding, and missing value imputation—were fitted exclusively on the training folds. The resulting parameters were applied to the validation and test sets, ensuring methodological transparency and reproducibility of the machine learning experiments.

Table 13 presents all the metrics used, along with their descriptions and interpretative value in the context of multiclass event safety classification.

For a comprehensive assessment of performance, model results were compared to evaluate the strengths and limitations of each approach in classifying individual classes. Such a comparative presentation enables the transparent selection of the optimal model and provides an analytical foundation for operational recommendations.

All results were calculated and saved in Excel format and then visualised using R packages and functions, ensuring transparency, reproducibility, and efficiency in the analysis. This approach facilitates the interpretation of results for both researchers and end users in maritime practice.

3. Results

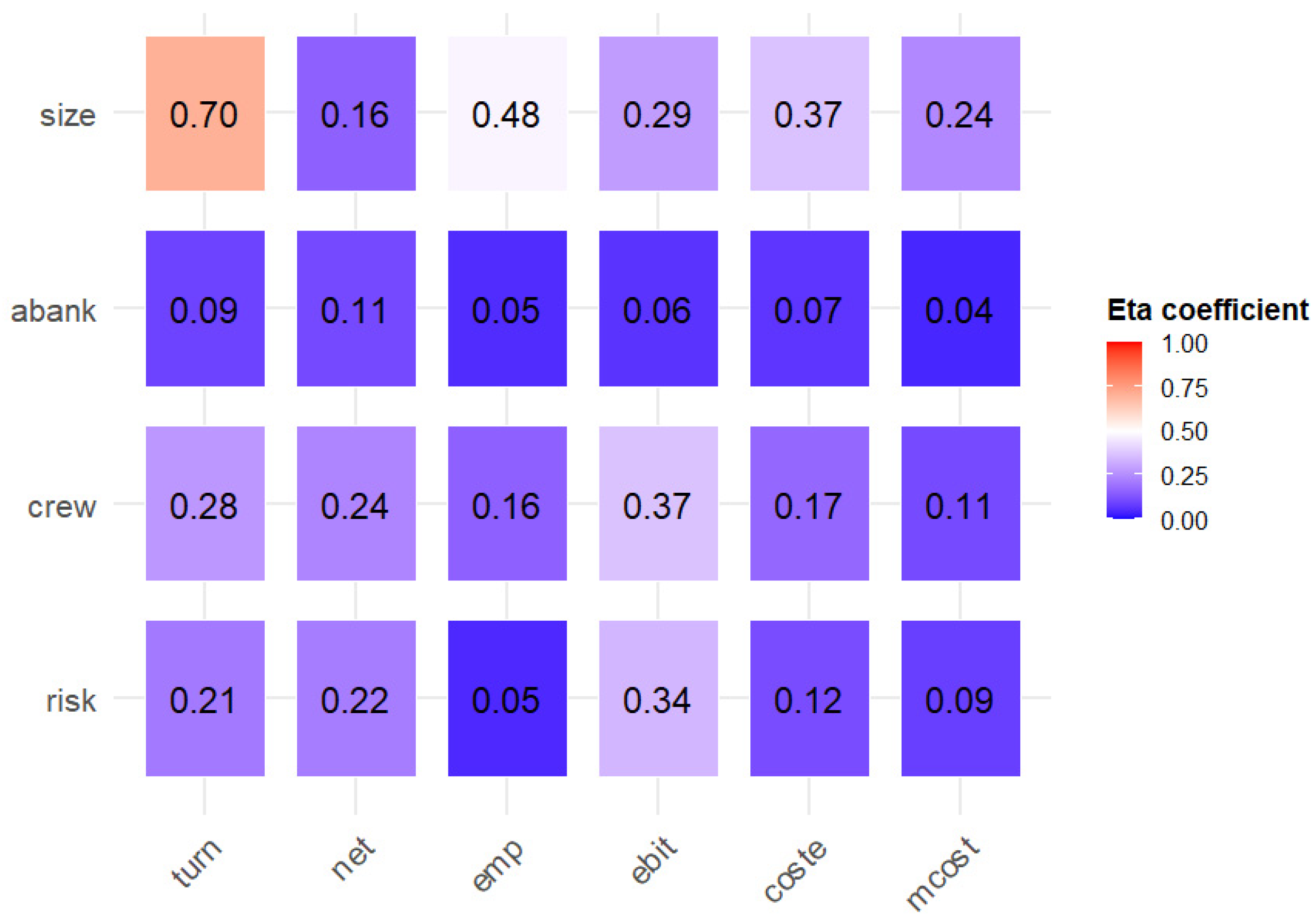

In line with the previously described methodological approach, an initial analysis of the relationships among variables was carried out using appropriate statistical measures: Cramér’s V for categorical variables, the Pearson correlation coefficient for numerical variables, and the Eta coefficient for relationships between categorical and numerical variables.

This preliminary analysis provides insight into the interrelationships and significance of key variables, forming the basis for the construction and evaluation of NNs in subsequent enterprise risk prediction.

Figure 2 presents the strength of association between the target variable “risk” and selected categorical operational variables (“crew”, “abank”, and “size”), expressed using Cramér’s V. The strongest association is observed between “risk” and “crew” (0.84), indicating that the number of employees has the greatest impact on risk. The relationship between “risk” and “abank” is moderate (0.49), while the association with “size” is considerably weaker (0.15), indicating a smaller effect of MSMEs’ size on risk.

Figure 3 presents the interrelationships among numerical variables, expressed using the Pearson correlation coefficient. The strongest positive correlation is between “turn” and “emp” (0.50), while moderate positive correlations are observed between “turn” and “ebit” (0.34) and between “turn” and “mcost” (0.43). The relationships between “net” and other variables are relatively weak, except for a moderate correlation with “ebit” (0.42). Other variables display low-to-moderate intercorrelations, indicating that most of these numerical indicators are partially independent of one another.

Figure 4 presents the strength of association between the categorical variables (“risk”, “crew”, “abank”, and “size”) and the numerical variables (“turn”, “net”, “emp”, “ebit”, “coste”, and “mcost”) as measured by the Eta coefficient. The strongest association is between “size” and “turn” (0.70), indicating that firm size has the greatest influence on turnover. There is also a notable relationship between “crew” and “ebit” (0.37), suggesting that the number of employees significantly affects earnings before interest and taxes. Other associations are of moderate or low intensity, reflecting a smaller impact of “abank”, “risk”, and other numerical indicators on the related metrics.

For the construction and evaluation of NNs, specifically the “NNET” and “MLP” models in R, a repeated stratified k-fold cross-validation (5-fold × 3 repetitions) procedure was employed (

R Documentation 2025). This approach ensures a robust estimation of model performance by quantifying variability across folds and mitigating the risk of bias due to a single random split. The dataset was partitioned into 15 stratified folds, preserving the class distribution in each fold. The models were trained and evaluated iteratively, with each fold serving as a validation set while the remaining folds constituted the training set. The final performance metrics were computed as fold-averaged values with standard deviations to reflect uncertainty.

For the “NNET” model, various hidden layer sizes (sizes = 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10) and regularisation rates (decays = 0.01, 0.1) were tested. The optimal configuration, selected based on cross-fold performance, was six neurons in the hidden layer with a decay of 0.1. For the “MLP” model from the RSNNS package, hidden layer sizes (MLP_sizes = 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10) were evaluated, and the optimal configuration consisted of five neurons in the hidden layer, yielding the best generalisation across folds.

This methodology ensures that both models are adapted to the data structure while maintaining robustness and minimizing overfitting. The cross-validation procedure provides a comprehensive assessment of model stability across different subsets of the data.

Table 14 presents the fold-averaged per-class metrics for the “NNET” and “MLP” models, including sensitivity, specificity, precision, F1 score, BA, QWK, Macro-PR-AUC, and MCC. These metrics highlight the models’ predictive performance and class-wise discrimination under repeated cross-validation.

Table 15 presents the cross-fold averaged performance metrics for the four models — “NNET”, “MLP”, MLR, and XGBoost — obtained through 5-fold cross-validation with 3 repetitions, allowing a comparative assessment of their predictive performance across multiple evaluation metrics.

The cross-validated results show that both “NNET” and “MLP” models achieve similar performance with and without the variable “crew”, indicating minimal contribution of this feature to overall model accuracy. Among all models, XGBoost slightly outperforms NNs on all four metrics (BA, MCC, QWK, and Macro-PR-AUC), while MLR shows lower performance, particularly on the ordinal-sensitive QWK. Variability across folds (SD) is small, confirming stable model estimates.

The

Appendix A contains a comprehensive set of supplementary tables and figures that provide a detailed evaluation of the models’ performance and interpretability.

Table A1 presents the complete set of per-class performance metrics for the “NNET” model estimated without the variable “crew”, showing how the classifier performs across classes A–E in terms of accuracy, error, and diagnostic measures.

Table A2 provides the corresponding per-class performance indicators for the “MLP” model under the same modelling conditions, allowing direct comparisons of the class-wise behaviour of both NNs’ architectures.

Table A3 summarises the cross-validated global metrics for the “NNET” and “MLP” models, offering an aggregated view of their predictive capability, calibration characteristics, and diagnostic strength across all classes.

In addition to the performance tables, several interpretability-oriented visualisations are included.

Figure A1 shows the global SHAP feature importance for both the “NNET” and “MLP” models, highlighting the relative contribution of each predictor to the overall decision-making process.

Figure A2 presents a local SHAP waterfall plot for selected instances, demonstrating how individual feature contributions cumulatively influence the model’s output at the observation level.

Figure A3 illustrates the reliability diagram for the XGBoost model, comparing predicted and observed class probabilities to assess model calibration and the alignment between estimated likelihoods and empirical frequencies.

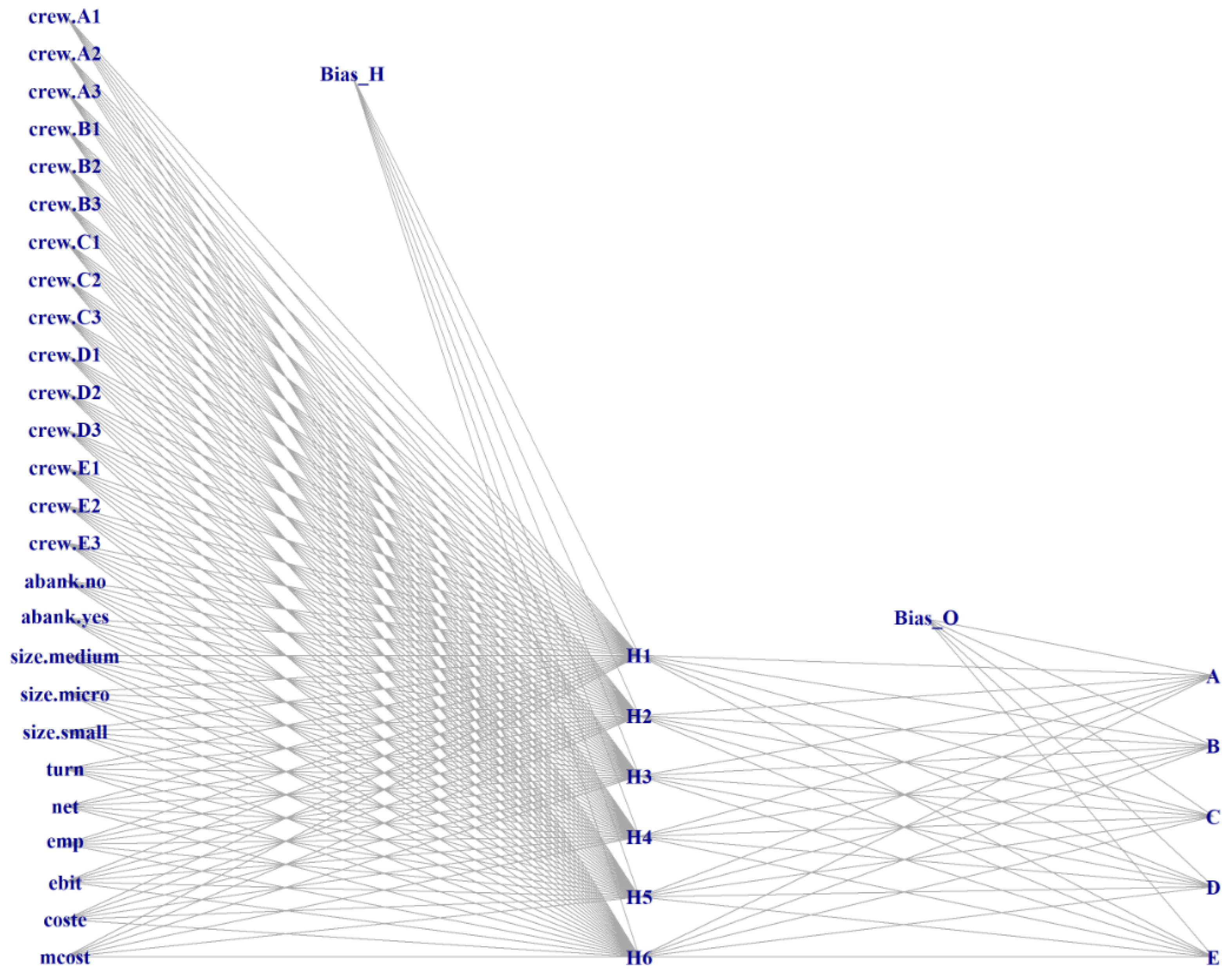

The “MLP” model from the RSANNS R package has five neurons in the hidden layer and does not use bias, meaning that neuron activations are computed solely from the weights of the input connections.

The

Figure 5 illustrates the “NNET” model architecture, consisting of 6 hidden neurons and 2 bias nodes, outlining the structural design of the network.

Figure 6 shows the graphical representation of the “MLP” network, illustrating the input layer, hidden layer, and output connections.

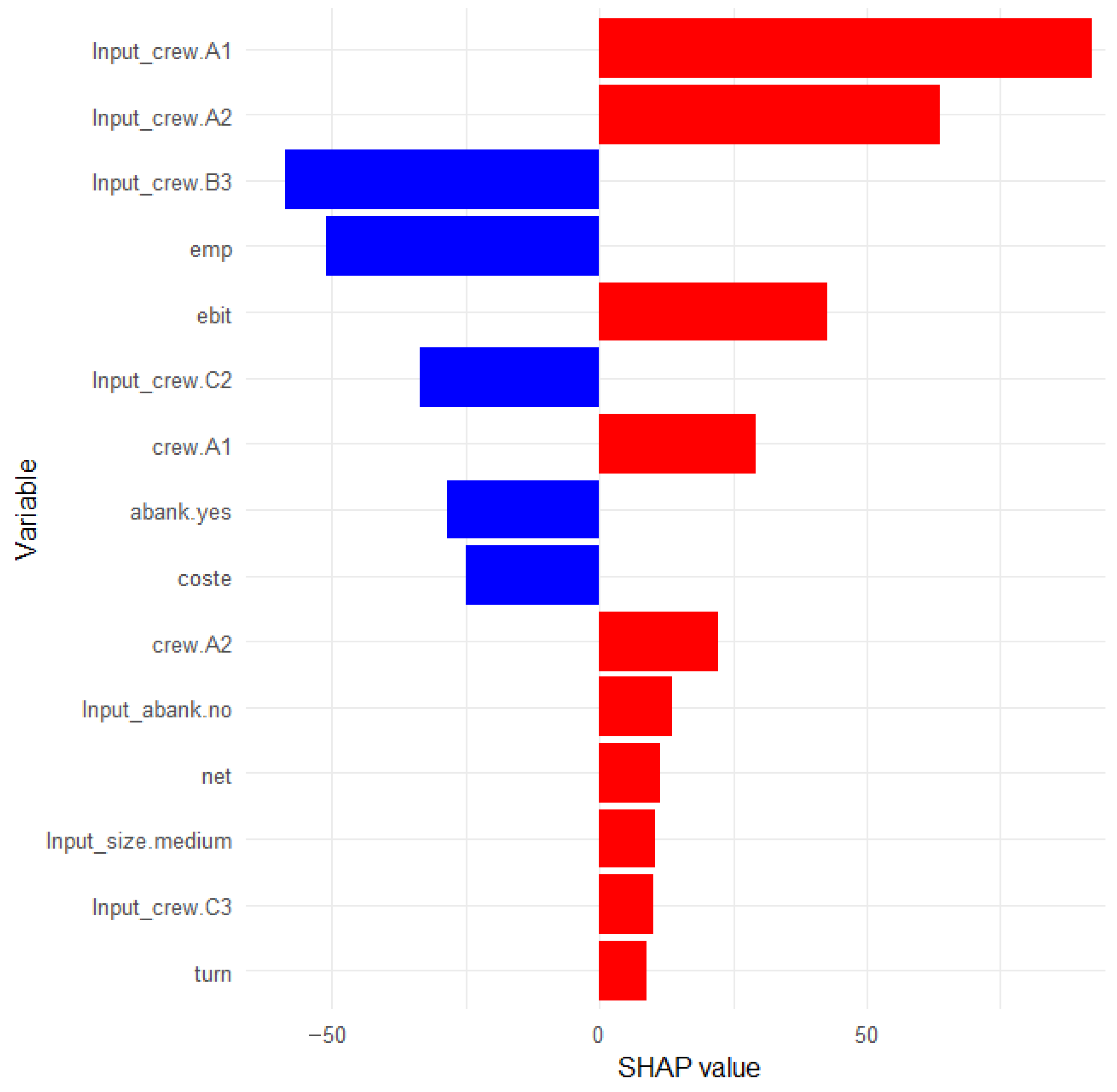

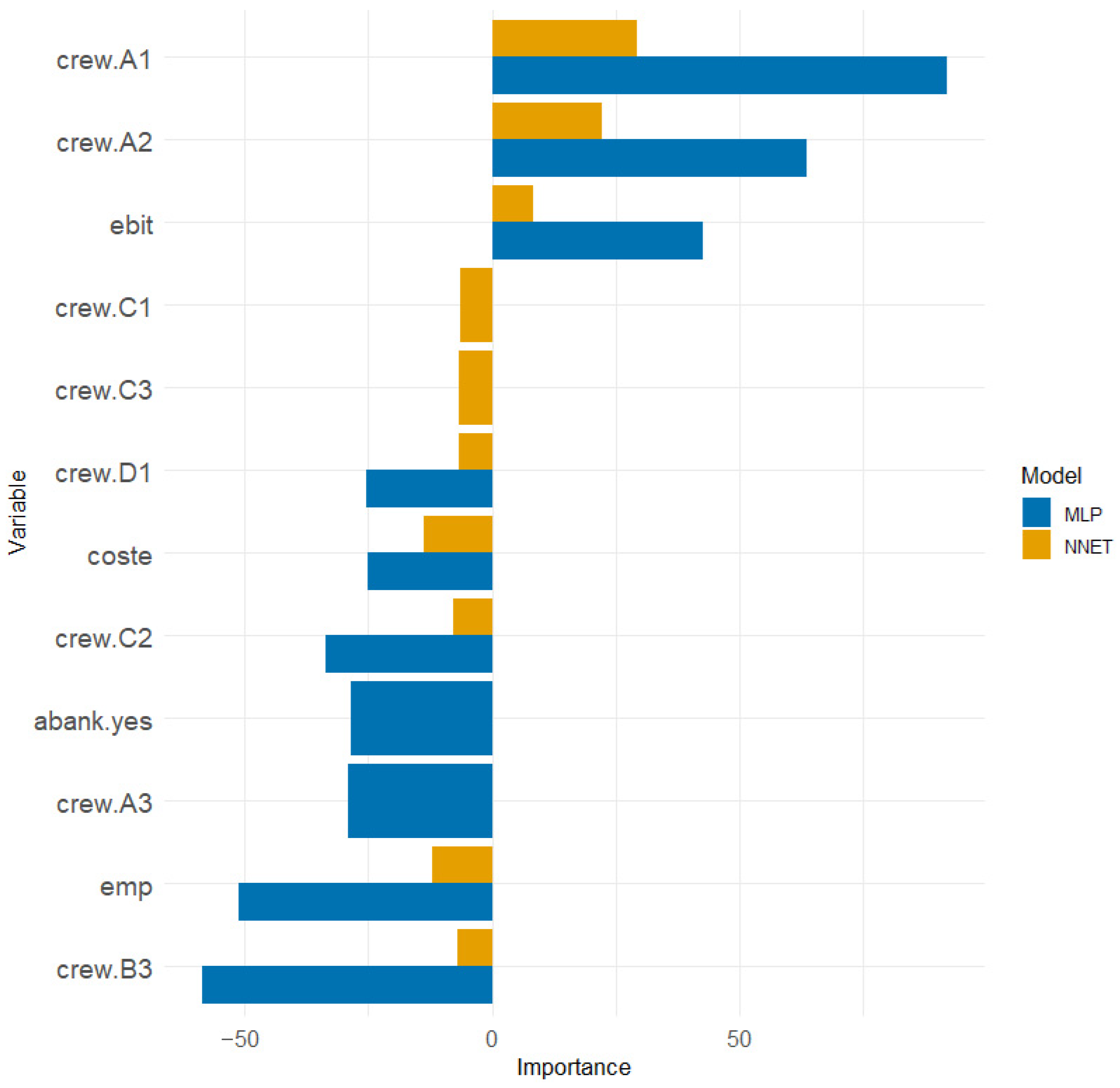

Figure 7 presents a comparative visualisation of the ten most important input variables for the optimally selected “NNET” and “MLP” models, trained on the defined training set.

All numerical and dummy variables are included, with categorical variables such as “crew,” “abank,” and “size” transformed into corresponding dummy variables. This results in more displayed variables than original attributes, as each categorical variable contributes multiple indicator variables, enabling the network to quantify their individual impact on predicting the target variable and risk. Analyses of the “NNET” model show that the key predictors of risk are specific categories of the number of employees, particularly “crew.A1” and “crew.A2,” while negative values for variables such as “emp” and “coste” indicate an inhibitory effect—an increase in these indicators reduces the predicted risk. The variables “turn” and “net” have moderate contributions, indicating that operational and financial indicators play a role but are not the primary determinants of risk in this model.

In the “MLP” model, the contribution structure is similar, but the intensity of effects differs—“crew.A1” and “crew.A2” dominate, while “ebit” and “emp” show pronounced negative or positive effects, reflecting the different functional interpretation of the hidden layer neurons in the “MLP” network.

Other dummy variables, though contributing less, reveal additional nuances in risk associated with specific employee categories, banking status, and firm size.

The comparative visualisation allows precise comparisons of variable importance between the “NNET” and “MLP” models and confirms the consistency in identifying key risk determinants. The figure highlights that operational structures and human resources, represented by the “crew” variables, are dominant factors in risk prediction, while financial metrics contribute to a lesser extent but remain relevant for finer risk differentiation. This analysis provides a solid basis for managerial and strategic decisions focused on controlling and optimising key risk factors.

Both confusion matrices (

Table 16) on the test dataset indicate very similar model performance. Class A maintains stable accuracy but shows noticeable confusion with class B. Class B is dominant and best recognised by both models, with “MLP” achieving slightly higher accuracy and fewer misclassifications. Class C experiences minor misclassification with B, indicating partial overlap in characteristics. Classes D and E are generally well classified, with errors mostly occurring in adjacent classes (C-D-E zone). Overall, “MLP” demonstrates slightly better performance than “NNET”, but without a significant difference in macro-level performance metrics.

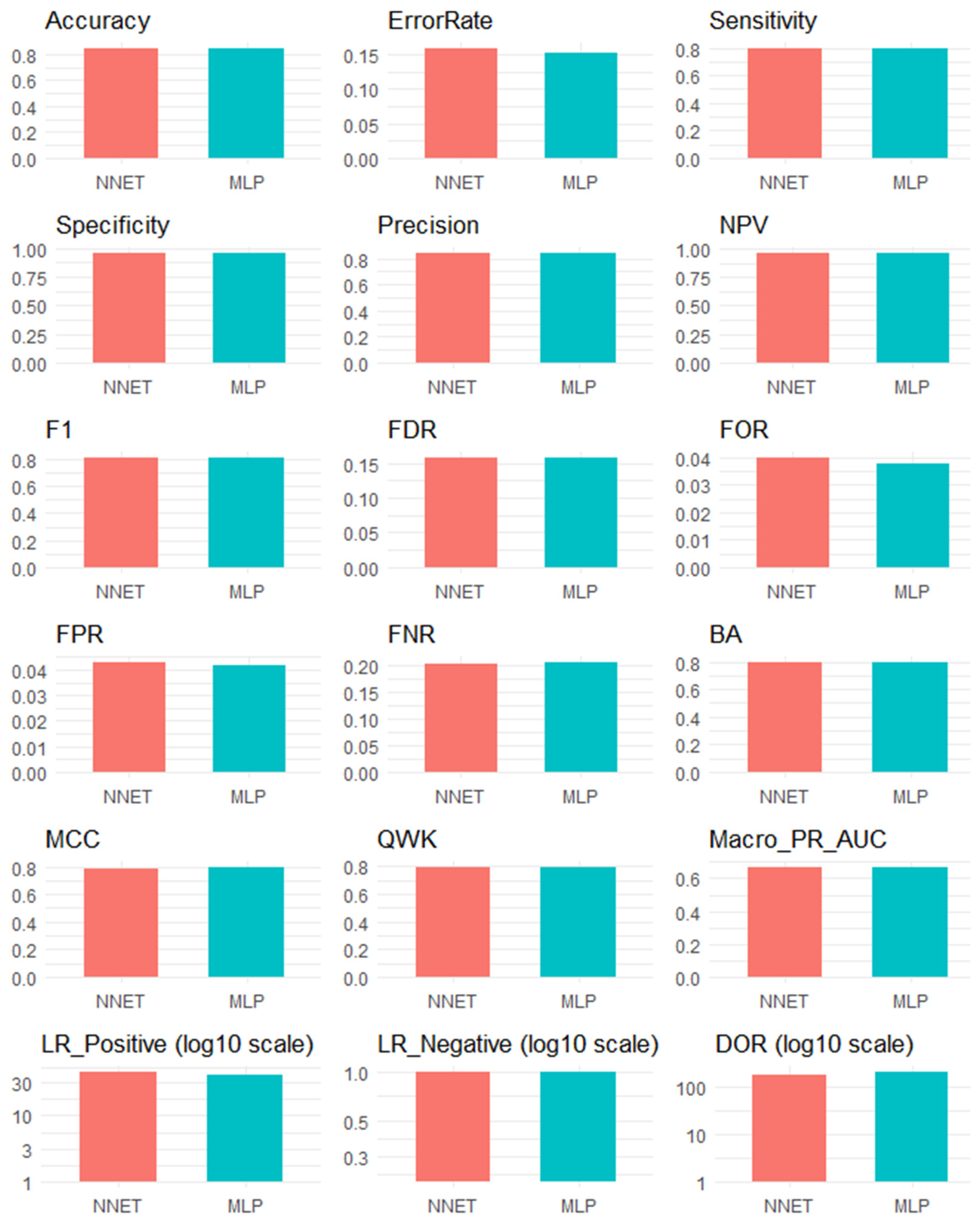

Figure 8 presents a comparative overview of the global performance of the two models, “NNET” and “MLP”, based on the accuracy, F1, and Kappa metrics. Both models achieve similar results. Accuracy is very close for both models (“NNET”: 0.841; “MLP”: 0.847), indicating comparable classification precision. The F1 scores are also nearly identical (“NNET”: 0.812; “MLP”: 0.811), showing that both models maintain a similar balance between precision and sensitivity. Kappa values are likewise very close, confirming good agreement between predicted and actual classes. The slight advantage of the “MLP” model in terms of accuracy may suggest a minor improvement in overall precision, but the difference is minimal and likely not statistically significant. This figure shows that the performance of both models is highly comparable, so model selection may depend on other factors, such as interpretability or training time.

Table 17 and

Table 18 present the class-specific performance metrics for both models on the test dataset across all classes, while

Table 19 provides a consolidated comparison of the overall metrics for “NNET” and “MLP”.

Based on

Table 19, the global metrics show that both “NNET” and “MLP” models achieve high classification accuracy and consistency. MCC and BA values of approximately 0.79 indicate a strong correlation between actual and predicted classes, with effective handling of imbalanced classes. The QWK confirms that the models maintain the correct order of ordinal classes, which is particularly important for ranked risk categories. However, the Macro-PR-AUC (around 0.67) suggests that precision in distinguishing rare or closely related classes could be improved. The “MLP” model demonstrates a slight advantage in prediction consistency, making it marginally more reliable for practical use in predictive analytics systems. These results, as shown in

Table 17, indicate that both models meet the fundamental robustness criteria, while also highlighting potential for optimisation in underrepresented classes.

Global metrics (

Table 19) were calculated so that accuracy and error rate were obtained directly from the overall confusion matrix, while all other metrics (sensitivity, precision, F1, etc.) are presented as averages across classes. This approach allows straightforward assessment of overall model performance while retaining insight into class-specific behaviour.

Figure 9 displays all metrics for the global models, enabling a straightforward visual comparison of their performance.

In addition to the basic model performance metrics and to better understand the efficiency of the NNs used, this section analyses the temporal and spatial complexity of the “NNET” and “MLP” algorithms implemented in R. The presented data enable comparison of the efficiency of both approaches in relation to network size, number of layers, and training set, which is critical for selecting an appropriate model depending on available resources and problem requirements.

Table 20 presents the temporal parameters of the training process for the “NNET” and “MLP” NN models. The “Total_Duration_sec” column indicates the total training time in seconds, while “Avg_Time_per_Config_sec” represents the average training time per hyperparameter configuration (size × decay). The results show that the “MLP” model was more time-efficient than the “NNET” model, with shorter total and average training times.

Table 21 provides a comparative analysis of the computational (time) and spatial (memory) complexity of the “NNET” and “MLP” algorithms implemented in R. The “NNET” algorithm represents a single-layer NN that uses the Broyden-Fletcher-Quasi-Newton optimisation method (

Al-Baali et al. 2014). This approach converges quickly for small models but requires significant memory and computational power because it involves computing and storing the Hessian matrix, resulting in quadratic complexity with respect to the number of weights (W

2). Therefore, “NNET” is suitable for smaller networks and limited datasets. In contrast, the “MLP” algorithm allows the construction of multilayer perceptrons that use stochastic gradient descent (SGD) for learning (

Tian et al. 2023). This method has linear time complexity relative to the number of connections between layers and does not require additional matrices for optimisation, which significantly reduces memory usage (

O(

W)). Consequently, “MLP” is more suitable for larger and more complex networks with multiple layers and samples.

4. Discussion

This study confirms that NNs can effectively model credit risk in the MSME sector, even when predictors are heterogeneous and partially interdependent. Both the preliminary correlation analysis and subsequent SHAP explanations consistently indicated that employee structure is the dominant risk factor. Although removing the “crew” variable did not alter the global performance metrics, SHAP results showed that employee-related attributes strongly influence the internal computations of the models through nonlinear interactions with other variables. This explains why aggregate metrics remain unchanged while the variable continues to play an important latent role in the modelling process.

The performance of the “NNET” and “MLP” architectures was highly stable across stratified 15-fold cross-validation, a crucial feature for imbalanced and ordinal classification tasks. Very small standard deviations across folds demonstrate the robustness of both models to sampling variability, strengthening their applicability in practical settings where the underlying data distribution may shift over time. Although their predictive metrics were nearly identical, differences in optimisation procedures and architectural design have practical consequences: “MLP” offers greater computational efficiency and scalability, whereas “NNET”, despite being slower and more memory-demanding due to BFGS optimisation, maintains reliable convergence in smaller configurations. This highlights the importance of considering computational constraints and problem size when selecting between comparable model families.

The expanded methodological framework significantly improved the robustness and credibility of the analysis. Repeated stratified k-fold cross-validation replaced the initial single split, providing stable estimates of model performance and enabling quantification of uncertainty through fold-averaged metrics and confidence intervals. Evaluation metrics were broadened to include those suitable for imbalanced ordinal outcomes—BA, MCC, QWK, and Macro-PR-AUC—while comprehensive confusion matrices clarified class-level performance. All preprocessing procedures were fitted strictly on training folds to prevent information leakage.

To contextualise NN performance, two benchmark models—regularised MLR and XGBoost—were incorporated. Their evaluation included probability calibration, multiclass Brier scores, and reliability diagrams, offering a fuller assessment of predictive reliability. An ablation analysis confirmed that the “crew” type variable did not introduce target leakage. The interpretability component was strengthened through SHAP-based global importance assessments and representative local explanations, demonstrating consistent feature contributions across resamples and enhancing the transparency of the modelling approach.

Overall, the revised methodology establishes a rigorous, well-validated, and interpretable pipeline for MSME credit risk prediction, aligning with modern standards in applied risk analytics and providing a robust framework for future decision-support systems.

5. Conclusions

The application of NNs, including the “NNET” and “MLP” models, in MSME risk assessment demonstrates high predictive accuracy and consistency in risk classification. The analysis indicates that human resources and the operational structure of enterprises dominate in risk prediction, while financial indicators contribute to more refined differentiation. However, the low interpretability of the models represents a significant limitation, making it difficult for management to understand the specific effects of individual variables on risk, which may restrict their practical application in strategic decision-making. Network performance strongly depends on the quality and quantity of data. Small samples, class imbalance, or data deficiencies can lead to overfitting and reduce the model’s ability to generalize to other enterprises or sectors. The network structure, choice of hyperparameters, and use of bias further influence the model’s stability and efficiency, requiring careful adjustment for each specific application.

Additionally, major limitations stem from the sensitivity of NNs to initial conditions and local minima of the error function, which can lead to result instability. The lack of transparency in the learning process prevents precise tracking of how the network makes decisions. NN models also often exhibit high computational complexity and require substantial training resources, which may limit their use in small organizations or when working with a large number of input variables. Scalability and transferability issues between different sectors present further challenges, as the structure and behaviour of data vary depending on the economic environment and regulatory context.

Future research should aim to combine the high predictive power of ANNs with the interpretability of other models through integration with regression or fuzzy systems, the use of regularization and data augmentation techniques, and the inclusion of dynamic and external economic indicators. Such an approach would enable a more robust and practically applicable MSME risk assessment, balancing predictive accuracy with result transparency, which is crucial for strategic risk management and informed decision-making.