Abstract

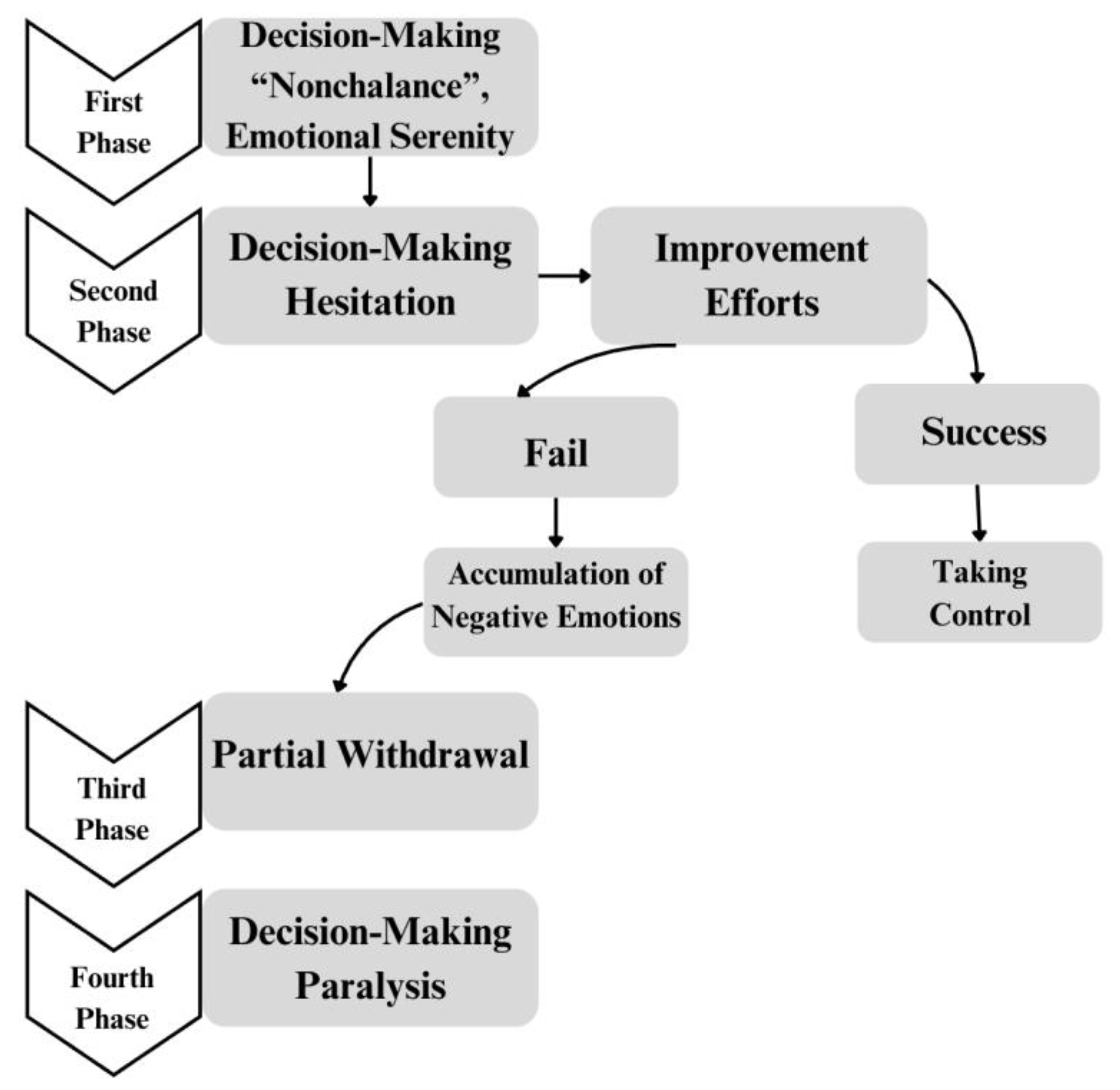

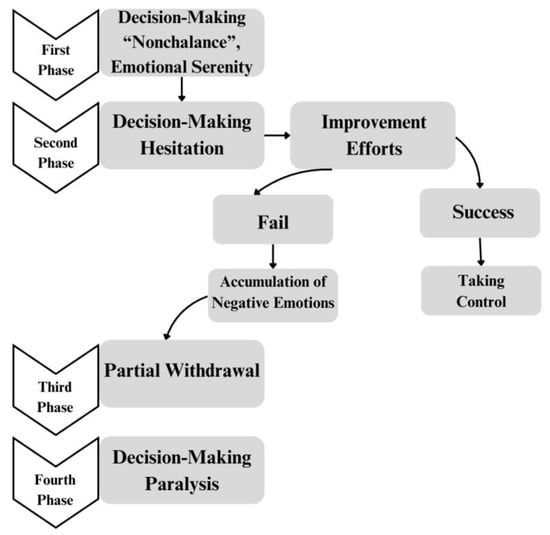

The association between emotions and decision-making is evident. Our article aims to demonstrate, for individual investors, the development of negative emotional charges on stock markets in a perceived negative trend. The research question concerns how negative emotions may be associated with specific behavioral responses. Our results indicate a four-phase process involving, first, decisional “nonchalance”; second, decisional hesitation; third, partial disengagement; and, finally, decisional paralysis. The first phase appears related to the lack of experience of the individual investor, the second phase corresponds to the uncertainty related to stock market operations, while the last two phases seem to coincide with a deteriorating decision-making environment and the accumulation of negative experiences, resulting from financial expectations not being met. Emotional paralysis raises questions about the possibility of individual investors renewing their investment strategies. These results come from a qualitative approach based on experimental finance and supported by the analysis of data from semi-structured interviews. Our study proposes a new four-phase model (nonchalance, hesitation, partial disengagement, and paralysis) that delineates the emotional and behavioral trajectories of individual investors during a perceived bear market. Our qualitative perspective also contributes to existing literature by highlighting the underexplored phase of “nonchalance”.

1. Introduction

The decision of an individual investor to participate in the stock market appears to depend largely on motivation, which refers to the desire to accomplish a task for the satisfaction it may bring (Kuhnen and Knutson 2005). The relationship between investment decisions and financial objectives (Raheja and Dhiman 2017) reflects the extent to which investments are perceived as meeting these objectives. However, stock markets are characterized by a high degree of uncertainty. Given the complexity of the environment in which financial decisions occur, individuals may rely on mental shortcuts to process the large amount of information provided by the stock markets (Tversky and Kahneman 1974).

These cognitive limitations are associated with the fact that individual investors tend to overlook relevant information and to make decisions that deviate from strict rationality (Nwosu and Ilori 2024). Boyle et al. (2004) observe that investment choices are often connected with emotional factors. Emotions appear to play an important role in individual investors’ attention and motivation (Richards et al. 2018), as the uncertainty related to the stock markets may correspond with a greater reliance on emotional signals during decision-making. Several studies suggest that repeated exposure to negative emotions may correspond to changes in reasoning and in the way options are evaluated (Lerner et al. 2015).

Based on a qualitative methodology, the scope of our research focuses on the expression of emotions in trading. Consistent with qualitative approaches, the formulation of our research question emerged from the study environment. Initially centered on the emotional aspects of decision-making, our methodological choices and the environment under analysis led us to refine our question as follows: to what extent is the accumulation of negative emotions associated with the development of phenomena of abandonment and withdrawal in the field of trading? Beyond identifying negative emotional states, our study also seeks to identify behavioral tendencies that accompany decision-making situations characterized by recurrent disappointment.

Although behavioral finance has largely documented associations between emotions and investment decisions, the literature emphasizes quantitative analyses and specific cognitive biases. Our study approaches this issue from a qualitative perspective to explore the psychological and emotional processes that appear linked to decision paralysis. Using an inductive methodology, we propose a four-phase model (nonchalance, hesitation, partial disengagement, and paralysis) that describes the trend in investors’ emotional and behavioral responses to a perceived bear market. This qualitative perspective offers a nuanced understanding of the complexity of participants’ experiences and highlights the process of negative emotion accumulation that is often ignored in quantitative studies. Despite extensive quantitative evidence regarding the role of emotions, few studies have explored the sequential emotional processes that correspond with inaction in bear markets.

Our results point to the existence of decision paralysis and provide insights into its origins, mechanisms, and underlying motivations.

2. State of the Art

2.1. The Emotional Involvement of Individual Investors

Decision-making processes seem to be subject to emotional factors; the human body would be comparable to a kind of “reservoir” of emotions that could be mobilized as soon as a situation refers to a past feeling. For this purpose, emotions would affect the selected options, facilitating accelerated and functional decision-making driven by the individual’s needs, objectives, and values. Therefore, decision-making on the stock markets could generate intense emotions. For example, past successes could create high expectations for the future, while losses could generate frustration that drives investors to intensify their efforts (Lo and Repin 2002).

The literature identifies the effects of emotional states on the decision-making process of individual investors. Positive emotions are said to encourage conservative behavior (Gabbi and Zanotti 2019): the investor feels that the situation is under control and that no further action is required (Van Dijk and Van der Pligt 1997). Conversely, negative emotions generated choices driven by a lack of patience (Herman et al. 2018). In general, the positive polarity of emotions increases along with returns in a bull market (Wang et al. 2014), boosting optimism (Grecucci and Sanfey 2014). On the other hand, negative emotions would encourage individual investors to make less satisfactory decisions (Ratner and Herbst 2005; Naseem et al. 2021). Moreover, some negative emotions could encourage increased risk-taking. For example, fear and sadness are associated with riskier decisions compared to other emotional states (Matsumoto and Wilson 2023). However, fear could also alter the rationality of financial choices since it would give priority to decisions based on instinct (Joshi and Badola 2022).

Other negative emotions involve withdrawal or risk-averse behavior. Anger, although a negative emotion, can facilitate impulsive decisions; it includes different nuances, ranging from exasperation to rage (Harmon-Jones et al. 2016). Conversely, disgust is characterized by strong emotional arousal and encourages avoiding unpleasant situations. Disgust is considered a primary emotion influencing the rejection of investment opportunities perceived as unfavorable. Anxiety, on the other hand, is a negative emotion that causes behavioral conflict, making decision-making more hesitant and difficult (Padmavathy 2024), which can result in suboptimal decisions as individual investors prefer not to take risks (Hartley and Phelps 2012; Bishop and Gagne 2018). Finally, sadness, although a low-intensity emotion, is often a response to loss and can make people take more risks (Matsumoto and Wilson 2023; Padmavathy 2024).

External stimuli could also intensify some emotional patterns. For example, using the red color on financial charts has been associated with increased fear, suggesting that some visual features could unconsciously influence their decisions (Bazley et al. 2021). Furthermore, stock market graphs are interpreted differently depending on the experience of the individuals: inexperienced individual investors express fear, anger, and sadness, while more experienced ones express disgust, happiness, arrogance, and commitment (Hsu and Marques 2023).

2.2. Looking Beyond Primary Emotions: The Role of Regret in the Decision-Making of Individual Investors

Some authors also mention the importance of complex emotions, particularly regret, in the decision-making process. Regret generally occurs when financial results do not meet expectations (Deng et al. 2025). Investors conclude that their results could have been more advantageous if they had chosen another option (Van Dijk and Zeelenberg 2005; Qin 2015) or even if they had chosen not to decide. The fact of not making any decision is equivalent to deciding (Al-Tarawneh 2012), and the concept of inaction is therefore relevant. This would encourage individual investors to invest more by taking risks in order to prevent the regret related to inaction (Qin 2015). Moreover, regret following a decision could drive individual investors to change their investment strategy even if it does not result in better financial results (Coricelli et al. 2007; Deuskar et al. 2021). Finally, they could decide to stop investing to avoid any kind of regret related to the investment strategy (Qin 2015).

On the one hand, investors try to avoid regret by not selling assets whose financial value has fallen, in the hope that they will rise again. On the other hand, the feeling of pride when the price of a security rises can encourage selling to realize gains (Sung 2007). The desire to minimize regret in investment decisions and to increase satisfaction and pride in successful transactions was highlighted by Strahilevitz et al. (2011). Individual investors tend to buy shares that they had previously sold with a gain, rather than those sold with a loss. In addition, they prefer to buy back shares whose value has decreased after a sale, rather than those whose price has increased. Finally, they are inclined to reinforce their positions in shares whose price has fallen since the initial purchase. Tsalatsanis et al. (2010) introduce the notion of “acceptable regret”, which refers to situations where a decision-maker accepts a degree of error, rather than being paralyzed by the fear of taking a decision. Summers and Duxbury (2012) distinguish emotions related to personal decisions (regret and satisfaction) from emotions resulting from independent outcomes (disappointment and excitement). Regret would encourage investors to hold shares that have fallen in price, while excitement leads to selling shares that have increased in value. This process is consistent with loss aversion, as initially formalized by Kahneman and Tversky (1979), which posits that individuals experience losses more intensely than gains, thereby influencing their risk-taking and withdrawal behaviors. Regret also interacts with several behavioral biases, such as anchoring, loss aversion, and the disposition effect (Shefrin and Statman 1985).

2.3. Negative Emotions and the Related Issue of Their Accumulation

When negative emotions accumulate without regulation, they could paralyze decision-making. Therefore, when a cycle of negative emotional charges starts to develop, sadness and anxiety are reinforced. This spiral can lead to a loss of interest or a feeling of emptiness. As a result of these negative emotions, some people use behavior designed to avoid them (Kross and Ayduk 2011). Withdrawal becomes a quasi-automatic response to an uncontrolled environment. Rather than looking for decision-making alternatives, individual investors try to avoid situations that could lead to a negative emotional state that would reinforce the lack of control (Gilbert and Allan 1998). The accumulated negative emotions can also induce emotional “fatigue” (Job et al. 2010). As the negative emotions intensify, cognitive efforts become increasingly difficult, making decisions more problematic (Frydman and Camerer 2016).

To address the decision-making paralysis, some authors mention the importance of mobilizing emotional regulation strategies. Emotional regulation helps people to modify their emotions according to their objectives (Gross 1998). In general, people prefer to increase the intensity of positive emotions and decrease the intensity of negative ones (Larsen 2000; Quoidbach et al. 2010). Emotional intensity can be modified through a number of strategies, such as cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression. Firstly, cognitive reappraisal involves reviewing the perception of a situation in order to reduce its emotional impact (Troy et al. 2013). Secondly, expressive suppression focuses on the physical expressions of emotions and aims to cover them up without acting on the emotion itself (Gross and Levenson 1993; Gross 2014; Maier and Seligman 2016).

3. Methodological Orientation and Experimental Protocol

We use an inductive approach based on a qualitative perspective. Inductive research is not commonly used in finance because it does not necessarily lead to generalization, as in deductive research. However, when applied to financial research, through the results generated, induction makes it possible to reinforce (Liu et al. 2022) or revise pre-existing theories (Casula et al. 2021). It also provides an understanding of how individuals behave and their perceptions in a specific environment (Vears and Gillam 2022; Prosek and Gibson 2021). Inductive studies consider a small number of controlled observations. For this purpose, we designed a controlled experiment to analyze the emotional dynamics that underlie decision-making on the stock markets. The general methodological approach described justifies the choice of analytical tools detailed in point 3.5.

In financial literature, experimental protocols are often described in a very small format, which raises the question of the reproducibility of the results (Serra 2017). However, being able to replicate a protocol is an essential principle in the experimental approach: the more a result is confirmed in a variety of contexts, the more its scientific robustness will be established (Walker et al. 2017). Despite the use of proven experiments that control the experimental variables, the assumptions underlying behavioral finance have been tested only very occasionally and through a small number of studies. For this purpose, the following points detail the experimental protocol put in place to address the issue of our research. Since we are working on the influence of emotions on decision-making processes, a qualitatively oriented methodology seems essential to address the individual investor’s psychological reality. Recently, qualitative methodologies have been receiving growing interest because of their ability to integrate a range of analytical approaches (Severin et al. 2022), as long as they consider variables related to individual personality (Floyd and List 2016). Moreover, emotional processes such as hesitation, avoidance, or decision paralysis are often treated as static outcomes rather than dynamic trajectories shaped by context and meaning. A qualitative approach, based on inductive reasoning, enables a deeper investigation of how emotions evolve over time, interact with cognitive biases, and influence decisions in situations of uncertainty. By giving voice to participants and reconstructing their subjective interpretations, such an approach complements quantitative findings and fills an important methodological gap in behavioral finance research (Vears and Gillam 2022).

3.1. Recruitment of Participants

The experiment was conducted in January 2025, hiring participants studying management sciences at a Belgian university. The first requests were sent at the end of October 2024. Students were asked to explain their motivations for participating. The only condition, in addition to their motivations, was to have successfully completed an introductory finance course in the second year of the course of study in order to have a minimum level of financial knowledge. No deadline was set to facilitate the collection of participants and to assess their motivation. After one week, ten applications were received, and eight of them met the criteria. Two applications were excluded for lack of motivation. The sample was limited to eight participants for two reasons: first, financial constraints, since the participants were paid, and second, because of the human resources needed to process the data.

Some experimental finance critics underline a gap between the psychological reality of students and professional traders. Nevertheless, the use of student samples is widely recognized and documented in experimental and behavioral finance, where it is often motivated by pragmatic and scientific reasons. Students are easier to recruit more homogeneous, which facilitates controlled data collection and reduces recruitment costs and time (Etchart-Vincent 2006; Kirchler 2009; Hanke et al. 2010; Bouattour and Martinez 2019). In addition, participants enrolled in finance-oriented programs generally demonstrate a satisfactory understanding of key financial concepts, trading mechanisms, and market dynamics, which ensures a level of familiarity sufficient for meaningful engagement in the experimental setting.

Empirical evidence further supports this methodological choice. Several studies show that students’ behavior under uncertainty and risk often corresponds to professionals, particularly regarding emotional and cognitive patterns (Porter and Smith 2003; Fréchette 2011; Abbink and Rockenbach 2006). In experimental markets, students reproduce speculative bubbles, herding, and overconfidence (Smith et al. 1988) and display comparable reactions linked to loss aversion, myopic loss aversion, and regret anticipation (Haigh and List 2005; Fréchette and Schotter 2015). These findings suggest that the underlying psychological and emotional mechanisms are consistent across populations, reinforcing the external validity of student-based experiments.

Our sampling strategy improves internal validity by limiting heterogeneity related to age and professional experience. Our aim being to investigate processes rather than population-level effects, a small and homogeneous sample is consistent with our exploratory and inductive design. Our approach provides qualitative insights that are transferable to similar contexts involving uncertainty, emotional stress, and decision fatigue. Data collected from semi-structured interviews provided an opportunity to document emotional trajectories and decision-making mechanisms that might have remained hidden in larger-scale quantitative settings.

3.2. The Stock Market Trading Platform

The stock market platform selected is ABC Bourse. Although some similar French-language stock market sites offer the opportunity to create virtual portfolios, they are not made for creating games. ABC Bourse gives the opportunity to build a virtual portfolio for EUR 100,000, allowing participants to place orders and analyze their effects on the value of the portfolio. The platform is also used to follow the real-time ranking, based on the value of their portfolio, which could, depending on the incentives of the experiment, increase or decrease emotional commitment. ABC Bourse also provides a range of macroeconomic and political information, company data, and technical analysis. This provides participants with a realistic environment in which to make decisions and an opportunity to analyze their strategies. Although the experiment did not involve real money, participants traded using virtual portfolios that replicated market conditions. The choice of a simulated environment was deliberate. This approach helped preserve the experimental validity by managing outside influences (minimizing ethical and financial risks for participants). Prior studies in behavioral finance have also shown that virtual trading environments can reproduce the emotional dynamics and decision-making pressures associated with real financial markets (Ackert et al. 2005; Etchart-Vincent 2006; Kirchler and Huber 2007).

To enhance emotional engagement and ecological validity, we incorporated competition-based incentives (performance rankings and feedback on portfolio evolution). These mechanisms are recognized for stimulating intrinsic motivation, stress responses, and affective involvement comparable to real money (Camerer and Hogarth 1999; Etchart-Vincent and L’Haridon 2011; Gabbi and Zanotti 2019). While the money was virtual, the emotional charges were psychologically significant, enabling participants to experience emotional reactions that correspond to real trading situations.

3.3. The Experimental Context

The experiment took place from 27 to 31 January 2025. The first three days (27 to 29 January) corresponded to the trading-related activities, and the last two (30 and 31 January) were dedicated to the semi-structured interviews. Participants were engaged in trading sessions divided into several periods.

3.4. Description of the Task to Be Carried out

Each participant worked on the ABC Bourse platform to carry out transactions on the CAC40 company shares. The CAC40 was chosen because the students were supposed to be familiar with this index. No instructions were given regarding the number of transactions. The experiment took place over 12 one-hour sessions, over the three days, with continuous assessment of the portfolios’ value, in order to introduce stress and to simulate real financial conditions. The portfolio’s initial composition seems to be a key element. Previous research (Finet et al. 2021) has revealed that initial portfolios consisting entirely of stocks and built by the organizers would encourage higher risk-taking, while an initial portfolio consisting entirely of cash would encourage more cautious behavior. For this experience, we used a portfolio consisting of cash. Unlike a quantitative experiment, whose objective is to test hypotheses by manipulating independent variables, our “experiment” was not intended to measure cause-and-effect relationships. Its role was to create a realistic and immersive environment that would facilitate emotional responses and decisions among participants. Our goal is not to highlight causal relationships but to explore how emotions are related to decision-making processes in uncertain market contexts. This controlled setting was essential to reproduce the conditions of stress and feeling uncertain experienced by investors in situations of loss and to provide the necessary context for the discussions that took place during the interviews.

3.5. Qualitative Tools Implemented

According to Pérez-Sánchez and Delgado (2022), in the majority of qualitative studies, data is mainly collected orally (21 out of 25 studies) but can also come from written documents (3 out of 25 studies) or focus groups (one study). Semi-structured interviews seem to be the most popular method in data collection procedures, although they are time-consuming (Opdenakker 2006). Semi-structured interviews offered the advantage of an individualized perspective compared to self-assessment questionnaires and focus groups (Adams 2015; Pin 2023). Indeed, semi-structured interviews provide an organized framework to explore topics while giving participants the opportunity to provide their own detailed answers (Ruslin et al. 2022). This flexibility would facilitate the analysis of emotional dynamics (Dolczewski 2022) by highlighting the interactions between emotional states and the stock market context. Many authors recommend conducting semi-structured interviews to clarify participants’ opinions (Gill et al. 2008; McIntosh and Morse 2015) and to explore the evolution of their emotions (Rocha 2021). This method requires an interview guide, which must be designed to help conduct the interviews (Adeoye-Olatunde and Olenik 2021). The data from the semi-structured interviews are examined through coding processes, which is a key step in the analysis, facilitating the classification of the information (Bailly and Nys 2018). The literature identifies three forms of coding: open coding, selective coding, and axial coding. These techniques aim to identify central categories from the data and their connections to subcategories that provide an analysis of the different elements of the research (Kristoforidis 2023).

In addition to the semi-structured interviews, we also gathered elements from participant observation. As the experiment progressed, data was collected regarding the reasons for the transactions and the tools used to justify the choices, as well as personal impressions of the progress of the experiment. These elements were delivered spontaneously by Vincent and Tremblay-Wragg (2021) and were used to support our analysis.

3.6. Data Collection Through Semi-Structured Interviews

The data collection was organized through semi-structured interviews, which took place immediately after the experimental phase. Each interview was recorded (with the students’ consent) and transcribed, and the data were analyzed through a double coding process. Data collection and analysis continued until thematic saturation was reached, meaning that no new themes or insights emerged from the interviews. Coder agreement between the two researchers was high, confirming the reliability of the thematic structure and consistency in the interpretation of emotional categories.

The semi-structured nature of the interviews facilitated consistency in the collection of information by following a pre-established set of thematic questions while providing the flexibility needed to explore unexpected topics or delve into the responses of some participants. This perspective facilitated the exploration of their perceptions, emotions, and decision-making processes. The interview guide was designed to address the following topics:

- The trend in participants’ emotions throughout the simulation.

- Their thoughts and reasons behind their investment decisions.

- Their perceptions of feeling uncertain and of loss.

- Specific moments when they felt hesitation or paralysis.

The complete version of the interview guide is provided in Appendix A for full transparency of our research protocol. We believe that this perspective (experiment + interviews) facilitates the generation of data that sheds light on the complexity of psychological processes in finance.

4. Results

4.1. General Context of the Experiment and Descriptive Statistics of the Sample

During the days of trading, the stock markets showed a slightly negative trend (see Table 1). Considering some indexes is intended to highlight the bearish stock market climate in which the experiment took place. The emergence of DeepSeek (unexpected) and the publication of LVMH’s annual results (scheduled for a long time and with negative informational content) negatively affected how the French index evolved. The negative influence of the emergence of DeepSeek occurred over the whole experiment, while LVMH’s annual results announcement mainly impacted the third day.

Table 1.

Daily returns (%) for selected stock indices (CAC 40, DJ 30, NASDAQ 100, TOPIX) over the period 27–29 January 2025.

The large number of men (see Table 2) corresponds to the conclusions of previous studies: a natural propensity of the male population to participate in activities with a playful dimension (Barber and Odean 2001; Finet et al. 2022). The majority of participants seemed to have some knowledge of how the stock markets work, which seems obvious given their background. Nevertheless, in order to be selected, some students may have boosted their knowledge.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of the sample.

4.2. Preliminaries to the Results

Semi-structured interviews were conducted by a single researcher (Adams 2015) in order, firstly, to provide continuity in the analysis. Secondly, the researcher in charge of the semi-structured interviews had no pedagogical relationship with the participants, which reinforces the independent nature of the students’ contributions. The average interview lasted between thirty minutes and an hour. Because the interviews were conducted in order to collect verbally expressed information, the flow of speech could differ from one person to another, which explains the variability in the number of words and sentences (Table 3). As previously said, each interview was conducted using an interview guide designed for an extensive discussion of a given issue (Smulowitz 2017; Adeoye-Olatunde and Olenik 2021). The interview guide was also designed for the organizer to be able to provide a different perspective based on the topic being discussed. The interviews were divided into three main phases with levels of porosity. The first phase aimed to introduce the discussion through general questions about the interviewee and their personal interest in trading. This phase is made to build trust between the interviewer and the interviewee. However, as the semi-structured interviews followed three days of trading involving interactions, the discussions quickly focused on the central object of the research. The second phase addressed how emotions played a part in the experiment. The last phase offered the interviewee the opportunity to address any points that had not been mentioned.

Table 3.

Descriptive characteristics of the semi-structured interviews conducted.

Each interview was recorded (with the students’ consent), transcribed, and the data were analyzed through a double coding process. This approach aims to strengthen reliability and to confirm the validity of the analyses by minimizing individual biases and ensuring an objective interpretation (Miles and Huberman 2003). The two researchers coded semi-structured interviews individually, each using a different software tool. The first researcher used Taguette, a free tool for analyzing qualitative data, and the second used Maxqda, which offers more features, such as the visualization of links between codes or the ability to calculate the occurrence frequency of words.

During the semi-structured interview coding, the researchers focused on the emotions expressed: the emotions identified in the transcripts were categorized according to the classification of Harmon-Jones et al. (2016): anger, fear, sadness, disgust, anxiety, happiness, desire, and relaxation.

By analyzing the emotional labels, the research question was formulated progressively throughout our data immersion, which corresponds to the inductive method. Indeed, even if our first purpose was an emotional “autopsy” in the field of decision-making, the nature of the data (strongly influenced by a negative stock market context) generated a focus on specific emotional issues. We are therefore investigating how the accumulation of negative emotions could paralyze investors’ decision-making. This question seems particularly relevant, given that some participants hardly traded at all on the last day, as illustrated in Table 4.

Table 4.

Direction of trading over the three days.

From how the coding processes were carried out, it can be seen that there is a high degree of consensus in the identification of emotions. Happiness, desire, disgust, and sadness were identified similarly. Some minor differences did arise, particularly concerning the distinction between fear and anxiety. One researcher sometimes referred to fear and anxiety when analyzing a statement, while the other focused on one or the other. Fear and anxiety correspond to a similar emotional intensity: they are expressed in response to a threat (Harmon-Jones et al. 2016). Fear is an instantaneous emotional reaction to a concrete threat, while anxiety is similar to anticipating a possible risk. Furthermore, in some cases, one researcher mentioned both happiness and desire, while the other researcher only referred to desire. These are nuanced interpretations of the data, but the analyses show a high degree of homogeneity. They also demonstrate the relevance of a double coding process. Our analysis has revealed different reasons for negative emotions in trading situations. We have chosen to focus our attention on emotions that arise during three key trading times: before making a purchase, after making a gain, and after making a loss (regardless of their size).

4.3. Early-Phase Emotional Dynamics in Investment Decision-Making

At the beginning, as no orders were placed, the participants could not be disappointed, and they navigated in a kind of decision-making “nonchalance”. The notion of “nonchalance” in decision-making has rarely been mentioned in the literature, except for some decisions made by teenagers (Reyna and Farley 2006). In our study, we consider it as a phase of positive mood. During this phase, choices are strongly influenced by personality and the psychological reality of the participants, since the experiment has just begun.

At first, I was happy, I couldn’t wait1.(I.7.)

From the first moments, we realized that most of the participants were not very familiar with how stock markets work. Some students seemed very anxious about placing an order. In fact, stock markets are related to uncertain environments in which the lack of control over the situation is said to be associated with anxiety related to discomfort (Grupe and Nitschke 2013). Anxiety often disturbs the decision-making process, which can lead to hesitation or aversion to investment options (Harmon-Jones et al. 2016). For this purpose, even if participants sometimes took a long time to make their decision, there was evidence of prudential attitudes even before choosing an investment option. Since anxiety is an emotion intended to anticipate the consequences of an event, it leads to cautious decision-making made for avoiding future loss (Gear et al. 2017). Here, we could mention the notion of anticipating regrets on the one hand and negative emotions on the other. Anticipation of regret refers to a process through which a person evaluates the consequences of choices as well as the emotion felt if another option would have been more preferable (Coricelli et al. 2007). Thus, the fear of regretting a decision led to the rejection of some trades (Brettschneider et al. 2025). Individual investors’ decisions are driven by the experience of emotions felt previously or the anticipation of emotions that may be generated (Brosch et al. 2013). The fact that people generally prefer to increase the intensity of their positive emotions and decrease the intensity of their negative emotions (Larsen 2000; Quoidbach et al. 2010) reinforces the argument that investment decisions are influenced by emotional defense mechanisms.

So when I moved on to a new order, I was completely in the dark. I had no idea how things would develop.(I.8.)

We are still hesitating.(I.5.)

The emotional instability experienced is caused by the conflict between the desire to act in order to achieve financial objectives and the uncertainty. Negative emotions, which are experienced prior to the decision-making process, do not necessarily disappear once the investment option has been chosen. While the emotion most experienced in a winning position was happiness, some participants also mentioned negative emotions (anxiety and fear). Despite the financially positive situation, our observations show concern about potential losses. This behavior corresponds to the prospect theory (Kahneman and Tversky 2013). Gain does generate happiness; however, this happiness is tempered by the anticipation of a loss.

There is still the fear that all this gain will ultimately fall back to zero.(I.4.)

Indeed, the hesitation between an immediately available gain versus a greater one in the future is amplified by the fear of losing an advantage that already exists. In the context of financial gain, the situation could therefore have a positive emotional charge, but it can also become a source of hesitation.

The most difficult thing about winning is knowing when to stop.(I.3.)

I find it more difficult to be in a situation where we are all in the green.(I.1.)

The anticipation of a profit can give rise to negative emotions, but the emotional intensity seems much more evident for the losing positions. Our analysis highlights a feeling of being powerless as the situation deteriorates, often combined with anxiety, disgust, or sadness. In contrast to gains, losses seem to lock some participants in a negative emotional cycle: not achieving positive results becomes central, and the person focuses only on this kind of experience. The loss of control limits the ability to make decisions and damages the individual’s self-image, intensifying negative emotions.

When I saw losses, I wondered whether I should sell to prevent it getting worse or whether I should wait and hope that things would improve. So, I was really lost and started to feel like a loser.(I.8.)

4.4. Decision-Making on Stock Markets: From Hesitation to Decision-Making Paralysis

Decision-making on the stock markets is influenced, on the one hand, by the search for a level of satisfaction (related to gains) and, on the other hand, by the desire to avoid regrets related to losses (Deng et al. 2025). Based on the assumption that loss-aversion behavior is negatively correlated with stock market participation (Conlin et al. 2015), we are trying to determine to what extent the accumulation of negative emotions could paralyze the decision-making process. As shown above, each key moment in the decision-making process (before making a purchase, after a win, and after a loss) generates hesitation. Thus, before making a purchase, the investor considers the investment option and the reasons that could result in a gain. Once the investment has been chosen, the question is whether to close the position, hold it, or even consolidate it. The individual investor is still in the hesitation phase: he does not know whether to sell the share to secure the gain or limit the losses, keep the losing position in expectation of a trend reversal, or buy back shares in order to reduce the unit cost price. In each of these scenarios, participants could try to improve the current situation. For example, some participants were looking for a strategy that would help them reverse the trend.

When you’re in the red, I want to make up for the gains, I want it to go up. You’re no longer motivated to get information, to work.(I.1.)

I was determined to make up for my gains.(I.7.)

Secondly, the accumulation of negative emotions can cause participants to partially disengage (the second phase). In fact, participation in the stock markets seems to depend on motivation (Kuhnen and Knutson 2005). Therefore, the lack of control over financial results can discourage investors from making decisions to improve their financial situation (Maier and Seligman 2016).

Some participants did indeed show a gradual loss of motivation as they considered their decisions to be inefficient.

I didn’t know what I could do. I said to myself, if I’m going to sell what I have, lose value, buy other things that will also go down, I might as well keep what I already have.(I.6.)

This behavioral withdrawal also reflects the ostrich effect (Karlsson et al. 2009), through which investors intentionally avoid financial information or market updates to minimize emotional discomfort and cope with negative experiences. As some participants moved from the hesitation phase to the partial disengagement phase, the likelihood of developing decision paralysis increased. We believe, on the one hand, that the bear market did not encourage participants to look for new investment opportunities because the experiment only lasted a small number of days, and they thought that the market would probably not change direction. On the other hand, the ranking seemed to be an emotional stress factor. The participants in the last positions at the end of the experiment felt that it was impossible to change the trend. Another question that could have been put forward is, since the financial commitment is not personal, why were they not inclined to adopt a high-risk strategy looking for rapid fluctuations? However, following the first three phases, our observation shows that the decision-making process has been paralyzed.

I said to myself, there’s nothing more you can do, because it’s the last day, and you see the stock market, there’s no miracle. I could only watch.(I.5.)

The last hour, I told myself that it was pointless. It seemed like it was over for me. I was second to last, so it was impossible to climb back up.(I.6.)

On the last day, let’s say in the afternoon, that’s when I saw that it was all over because the experience was almost at an end. And I could see that I was in the red. At a certain point, it just made me laugh. That’s when I stopped playing.(I.7.)

Full withdrawal.(I.8.)

Our data show that half of the participants have given up all efforts to improve the financial results. The accumulation of negative emotions combined with repeated disappointments seems to have contributed to emotional fatigue, with a decline in attentional resources and a strong decrease in the motivation to carry out transactions (Gross 2014). It becomes too costly to make decisions in terms of cognitive effort and emotional involvement. This results in decision-making paralysis: the participants no longer see any positive outcome and feel like victims of the stock market’s complexity. Lastly, people are just exhausted by overexposure to stock market websites, with their constant flow of information and continuously updated graphics (Guo et al. 2023).

To enhance transparency and traceability between the empirical data and the four-phase model, Table 5 summarizes the main emotions identified during each stage of the decision-making process. It highlights the corresponding behavioral markers, provides illustrative quotations from participants, and offers an analytical interpretation linking emotional experiences to decision outcomes. The four-phase trajectory identified here extends existing theories by linking loss aversion and regret anticipation into a unified process. Whereas most studies treat these biases as separate drivers of suboptimal behavior, our results reveal their interdependence over time, suggesting that emotional fatigue mediates the transition from hesitation to paralysis. This highlights the importance of considering temporal and affective dimensions in understanding behavioral biases.

Table 5.

Thematic analysis of emotional and behavioral reactions during the decision-making process.

5. Discussion

In terms of discussion, we connect our results to loss aversion, one of the most important cognitive biases explaining individual investor behavior (Kahneman and Tversky 2013; Barberis 2013). Contrary to expected utility theory, loss aversion highlights the psychological pain of a loss, perceived with greater intensity than the pleasure of a gain of similar value (Barberis and Xiong 2009). Our qualitative analysis identifies an “emotional aversion to loss” that influences investor behavior beyond a reaction to financial disappointment. It interferes with the anticipation of gain, creating psychological tension (Rick 2011). Even when participants make profits, they cannot help worrying about the possibility of future losses. This “anticipated discomfort” serves to prevent them from happiness, turning success into a source of potential anxiety (Knutson et al. 2008). The fear of losing an advantage already gained becomes stronger than the excitement of a greater potential gain, leading to favoring money preservation over return optimization (Imas 2016). This can result in investors selling winning stocks too early, at the risk of missing out on larger returns. The impact of loss aversion is also evident after a loss: loss generates negative emotions, including helplessness, anxiety, disgust, and decision paralysis (Frydman and Camerer 2016; Hartley and Phelps 2012). This inertia, which at first seems irrational, is a psychological protection mechanism. Rather than selling a losing asset (and thus having to deal with the pain of a loss), investors prefer to hold on to the hope that the asset will be appreciated in the future. This tendency is a consequence of loss aversion. Individuals try to avoid regretting selling an asset at a price that was too low and that could have been better in the future (Zeelenberg and Pieters 2007). The fear of regret can result in an accumulation of underperforming assets (Summers and Duxbury 2012). Our interviews illustrate how emotions and cognitive biases can override rationality (Lerner et al. 2015). Our article does not ignore “normal” decision-making, such as selling, but it explains the psychological mechanisms (decision paralysis, loss aversion, fear of regret, and emotional fatigue) that, in a bear market and an accumulation of disappointments, can drive investors towards inaction.

6. Conclusions, Limitations, and Avenues for Future Research

Our results provide evidence for analyzing decision paralysis in the context of decision-making on the stock markets. By looking at the emotions that arise before making an investment decision and following a gain or loss, we highlight how emotions could cause decision paralysis. Basically, the accumulation of negative experiences (and the resulting negative emotions) would result in some participants withdrawing from the decision-making process due to a lack of motivation. Our research shows that it occurs at the end of a cycle of several phases.

Before the experiment begins, the participants have not yet been emotionally affected by the decisions, since no decisions have been made. This is what we call the “nonchalance” phase. Then, from the beginning of the experiment, each decision generates a financial result that, for some, does not meet their expectations. They then try to improve their financial performance by making other types of decisions. These efforts seem to produce results for some individual investors, giving them the feeling of being able to take back control of the financial situation (see Table 5). However, for others, these efforts to improve remain ineffective, failing to produce the expected results. As a result, as they experience failure and develop negative emotions, they lose the motivation to change the trend and enter the third phase of the process: the initial positive expectations are invalidated and turn into negative expectations (fear of regret overrides the desire to take risks). This phase corresponds to a partial disengagement related to the demotivation of individual investors whose decisions are seen as unfounded. According to this process, individual investors enter the last phase, where the decision-making process is paralyzed. Participants prefer not to take any more risks in order to avoid further disillusionment (see Table 6). Figure 1 illustrates the process that could lead to decision-making paralysis.

Table 6.

Applying the decision-making paralysis process to the case of experimentation.

Figure 1.

Process of decision-making paralysis: summary. Source: authors.

Our results corroborate the conclusions drawn from behavioral finance and open new research avenues, particularly in declining markets. By extending our four-phase structured analysis model to other types of investors (particularly institutional ones), the understanding of speculative bubble explosions—even if, in this case, it is a question of massive sale movements—could be analyzed from a new perspective. Given the small and homogeneous sample (eight participants, including one woman), our findings should be interpreted as exploratory. The study aims to explore psychological and emotional mechanisms rather than to produce generalizable results. In line with qualitative research principles, the validity of the findings relies on transferability rather than generalization: readers are provided with sufficient contextual detail to assess the relevance of these insights to other settings or populations (Guba and Lincoln 1994; Nowell et al. 2017).

In terms of avenues for future research, although the semi-structured interviews were subjected to a double coding process, emotions remain difficult to identify without additional measurement. Other studies could combine qualitative direction with neurophysiological measurements, such as changes in heartbeat, to measure emotional reactions. Furthermore, because our approach focuses on a single emotional label, we could also consider working by using emotional combinations and analyzing the mutual influence of emotions. For example, for an emotional combination consisting of surprise and disgust, the analysis would focus on how a negatively polarized surprise could influence the development of intense negative emotional charges.

Moreover, time horizon may also play a role in decision-making paralysis. Investors with shorter horizons might perceive greater control and experience lower emotional fatigue. Future studies could integrate this dimension to refine understanding of emotional trajectories. Extending the trading period (which also implies additional costs) could produce other emotional and decision-making patterns. In particular, it would be interesting to analyze the extent to which a change in market trends would cause emotional changes.

Finally, using a larger population would help to consider a deductive analysis and to provide generalizable results. It should be noted that financial constraints prevented us from increasing the size of our sample. Similarly, future research could integrate mixed methods to test the robustness of the proposed model.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.F.; investigation, A.F., K.K., and J.L.; resources, K.K. and J.L.; data curation, K.K. and J.L.; writing—original draft preparation, A.F., K.K., and J.L.; writing—review and editing, A.F., K.K., and J.L.; supervision, A.F.; project administration, A.F.; funding acquisition, A.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Walloon-Brussels Federation (Belgium) through a Concerted Research Action (Grant Number: ARC-25/29 UMONS5).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study as the research involved minimal risk to participants and data were collected anonymously through a simulation-based educational activity.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the participants to publish this paper. Participants were informed about the purpose and procedures of the simulation, and participation was voluntary.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Availability Bias

- Can you tell me about your research on the companies you wanted to invest in?

- What kind of information were you looking for?

- What type of information were you prioritizing?

- How has information accessibility impacted your operations?

Overconfidence

- How do you rate your trading skills?

- How did you feel after a successful series of moves?

- How has this influenced your trading behavior?

- Do you think you underestimated the risks at times?

Anchoring Bias

- When you decide to sell stock, how did the purchase price influence it?

- How have past price levels influenced your decisions?

- Why did the initial purchase value prevent you from adapting to new information?

Herd Behavior

- What was the main influence on your choosing one action over another?

- How have general trends influenced your decisions?

- How did you react to market movements in situations of high activity?

Prospect Theory

- What would you do if you had a winning stock or a losing stock in your portfolio?

- What were your motivations for selling winning positions, even though they could still bring you additional profits in the future?

- What were your motivations for maintaining a losing position?

General Emotions

- In your opinion, what role did emotions play in this experiment?

Emotions Changes

- After a session where you made several decisions that were unsuccessful, how did you react emotionally, and how did this influence the next session?

- Have you noticed changes in your emotions or behaviors when you have several successive losses?

- Do you feel like your emotions have changed the way you’ve structured your strategy over time?

Impact of Emotions on Decision-Making

- Before placing an order, what kind of emotions did you usually feel?

- Can you describe a situation where your emotions directly influenced your decision-making, whether in a losing or winning situation?

- Have there been times when, despite feeling stressed or anxious, you were able to make a successful decision?

- Do you feel like your emotions have changed the way you structured your strategy over time?

Reactions to Gains or Losses

- How did you react to loss?

- Have the losses affected your decisions?

- How did you react to a gain?

- Did you react more impulsively afterward?

Emotion Management

- How did you handle the pressure of making decisions quickly?

Did the breaks between each session influence your emotions?

Note

| 1 | It should be remembered that all the verbatim reports have been reproduced exactly as they were recorded, and therefore, they may be very spontaneous. |

References

- Abbink, Klaus, and Bettina Rockenbach. 2006. Option pricing by students and professional traders: A behavioural investigation. Managerial and Decision Economics 27: 497–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackert, Lucy F., Bryan K. Church, James Tompkins, and Ping Zhang. 2005. What’s in a name? An experimental examination of investment behavior. Review of Finance 9: 281–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, William C. 2015. Conducting semi-structured interviews. In Handbook of Practical Program Evaluation. Hoboken: Wiley, pp. 492–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeoye-Olatunde, Omolola A., and Nicole L. Olenik. 2021. Research and scholarly methods: Semi-structured interviews. Journal of the American College of Clinical Pharmacy 4: 1358–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Tarawneh, Hussien Ahmad. 2012. The main factors beyond decision making. Journal of Management Research 4: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailly, Denis, and Cecile Nys. 2018. Methodology guide for semi-structured interviews. Research Gate 20. Available online: https://hal.science/hal-02154155/ (accessed on 16 August 2025).

- Barber, Brad M., and Terrance Odean. 2001. Boys will be boys: Gender, overconfidence, and common stock investment. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 116: 261–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barberis, Nicholas, and Wei Xiong. 2009. What drives the disposition effect? An analysis of a long-standing preference-based explanation. The Journal of Finance 64: 751–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barberis, Nicholas C. 2013. Thirty years of prospect theory in economics: A review and assessment. Journal of Economic Perspectives 27: 173–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazley, William J., Henrik Cronqvist, and Milica Mormann. 2021. Visual finance: The pervasive effects of red on investor behavior. Management Science 67: 5616–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, Sonia J., and Christopher Gagne. 2018. Anxiety, depression, and decision making: A computational perspective. Annual Review of Neuroscience 41: 371–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouattour, Mondher, and Isabelle Martinez. 2019. Hypothèse d’efficience des marchés: Une étude expérimentale avec incertitude et asymétrie d’information. Finance Contrôle Stratégie, 22-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, Glenn, Andrew Hagan, R. Seini O’Connor, and Nick Whitwell. 2004. Emotion, fear and superstition in the New Zealand stockmarket. New Zealand Economic Papers 38: 65–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brettschneider, Julia, Giovanni Burro, and Vicky Henderson. 2025. Make Hay While the Sun Shines: An Empirical Study of Maximum Price, Regret, and Trading Decisions. Journal of the European Economic Association 23: 594–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosch, Tobias, Klaus Scherer, Didier Grandjean, and David Sander. 2013. The impact of emotion on perception, attention, memory, and decision-making. Swiss Medical Weekly 143: w13786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camerer, Colin F., and Robin M. Hogarth. 1999. The effects of financial incentives in experiments: A review and capital-labor-production framework. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 19: 7–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casula, Mattia, Nandhini Rangarajan, and Patricia Shields. 2021. The potential of working hypotheses for deductive exploratory research. Quality & Quantity 55: 1703–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conlin, Andrew, Petri Kyröläinen, Marika Kaakinen, Marjo-Riitta Järvelin, Jukka Perttunen, and Rauli Svento. 2015. Personality traits and stock market participation. Journal of Empirical Finance 33: 34–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coricelli, Giorgio, Raymond J. Dolan, and Angela Sirigu. 2007. Brain, emotion and decision making: The paradigmatic example of regret. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 11: 258–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Xue, Zhi Li, Tiantian Zhang, and Wen Zhou. 2025. Portfolio Decision and Risk Analysis with Disappointment and Regret Emotions. IAENG International Journal of Applied Mathematics 55: 407. [Google Scholar]

- Deuskar, Prachi, Deng Pan, Fei Wu, and Hongfeng Zhou. 2021. How does regret affect investor behaviour? Evidence from Chinese stock markets. Accounting & Finance 61: 1851–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolczewski, Michał. 2022. Semi-structured interview for self-esteem regulation research. Acta Psychologica 228: 103642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etchart-Vincent, Nathalie. 2006. Expériences de laboratoire en économie et incitations monétaires. Revue d’Économie Politique 116: 383–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etchart-Vincent, Nathalie, and Olivier l’Haridon. 2011. Monetary incentives in the loss domain and behavior toward risk: An experimental comparison of three reward schemes including real losses. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 42: 61–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finet, Alain, Kevin Kristoforidis, and Robert Viseur. 2021. L’émergence de biais comportementaux en situation de trading: Une étude exploratoire. Recherches en Sciences de Gestion 146: 147–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finet, Alain, Robert Viseur, and Kevin Kristoforidis. 2022. De la composante genre dans les activités de trading: Une étude exploratoire. La Revue des Sciences de Gestion 313: 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floyd, Eric, and John A. List. 2016. Using field experiments in accounting and finance. Journal of Accounting Research 54: 437–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fréchette, Guillaume R. 2011. Laboratory Experiments: Professionals Versus Students. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1939219 (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Fréchette, Guillaume R., and Andrew Schotter, eds. 2015. Handbook of Experimental Economic Methodology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Frydman, Cary, and Colin F. Camerer. 2016. The psychology and neuroscience of financial decision making. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 20: 661–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabbi, Giampaolo, and Giovanna Zanotti. 2019. Sex & the City. Are financial decisions driven by emotions? Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance 21: 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gear, Tony, Hong Shi, Barry J. Davies, and Nageh A. Fets. 2017. The impact of mood on decision-making process. EuroMed Journal of Business 12: 242–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, Paul, and Steven Allan. 1998. The role of defeat and entrapment (arrested flight) in depression: An exploration of an evolutionary view. Psychological Medicine 28: 585–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, Paul, Kate Stewart, Elizabeth Treasure, and Barbara Chadwick. 2008. Methods of data collection in qualitative research: Interviews and focus groups. British Dental Journal 204: 291–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grecucci, Alessandro, and Alan G. Sanfey. 2014. Emotion regulation and decision making. In Handbook of Emotion Regulation, 2nd ed. New York. [Google Scholar]

- Gross, James J. 1998. The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Review of General Psychology 2: 271–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, James J. 2014. Emotion regulation: Conceptual and empirical foundations. Handbook of Emotion Regulation 2: 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Gross, James J., and Robert W. Levenson. 1993. Emotional suppression: Physiology, self-report, and expressive behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 64: 970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grupe, Dan W., and Jack B. Nitschke. 2013. Uncertainty and anticipation in anxiety: An integrated neurobiological and psychological perspective. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 14: 488–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guba, Egon G., and Yvonna S. Lincoln. 1994. Competing paradigms in qualitative research. In Handbook of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, pp. 105–17. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Yameng, Yiting Liu, Zhiyuan Pan, and Guoqin Bu. 2023. The Impact of Information Overload on Investment Decisions under the Information Disclosure System of STAR Market. Advances in Economics, Management and Political Sciences 4: 174–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haigh, Michael S., and John A. List. 2005. Do professional traders exhibit myopic loss aversion? An experimental analysis. The Journal of Finance 60: 523–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanke, Michael, Jürgen Huber, Michael Kirchler, and Matthias Sutter. 2010. The Economic Consequences of a Tobin Tax—An Experimental Analysis. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 74: 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmon-Jones, Cindy, Brock Bastian, and Eddie Harmon-Jones. 2016. The discrete emotions questionnaire: A new tool for measuring state self-reported emotions. PLoS ONE 11: e0159915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, Catherine A., and Elizabeth A. Phelps. 2012. Anxiety and decision-making. Biological Psychiatry 72: 113–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, Aleksandra M., Hugo D. Critchley, and Theodora Duka. 2018. The role of emotions and physiological arousal in modulating impulsive behaviour. Biological Psychology 133: 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Hsin-Tzu, and João Alexandre Lobo Marques. 2023. Neurofinance: Exploratory Analysis of Stock Trader’s Decision-Making Process by Real-Time Monitoring of Emotional Reactions. In 18th European Conference on Management, Leadership and Governance. Reading: Academic Conferences and Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Imas, Alex. 2016. The realization effect: Risk-taking after realized versus paper losses. American Economic Review 106: 2086–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Job, Veronika, Carol S. Dweck, and Gregory M. Walton. 2010. Ego depletion—Is it all in your head? Implicit theories about willpower affect self-regulation. Psychological Science 21: 1686–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, Chandra, and Sneha Badola. 2022. Behavioural biases in finance: A literature review. International Journal of Research and Analytical Reviews 9: 269–74. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman, Daniel, and Amos Tversky. 1979. Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk. Econometrica 47: 263–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, Daniel, and Amos Tversky. 2013. Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. In Handbook of the Fundamentals of Financial Decision Making: Part I. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing, pp. 99–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, Niklas, George Loewenstein, and Duane Seppi. 2009. The ostrich effect: Selective attention to information. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 38: 95–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchler, Michael. 2009. Underreaction to fundamental information and asymmetry in mispricing between bullish and bearish markets. An experimental study. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 33: 491–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchler, Michael, and Jürgen Huber. 2007. Fat tails and volatility clustering in experimental asset markets. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 31: 1844–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knutson, Brian, Jamil P. Bhanji, Rebecca E. Cooney, Lauren Y. Atlas, and Ian H. Gotlib. 2008. Neural responses to monetary incentives in major depression. Biological Psychiatry 63: 686–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristoforidis, Kevin. 2023. Lorsque le rideau rouge est abaissé: La scénarisation de la croissance dans les Industries Culturelles et Créatives wallonnes. Doctoral thesis, UMONS—University of Mons, Mons, Belgium. Available online: https://orbi.umons.ac.be/handle/20.500.12907/47207 (accessed on 21 March 2025).

- Kross, Ethan, and Ozlem Ayduk. 2011. Making meaning out of negative experiences by self-distancing. Current Directions in Psychological Science 20: 187–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhnen, Camelia M., and Brian Knutson. 2005. The neural basis of financial risk taking. Neuron 47: 763–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, Randy J. 2000. Toward a science of mood regulation. Psychological Inquiry 11: 129–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, Jennifer S., Ye Li, Piercarlo Valdesolo, and Karim S. Kassam. 2015. Emotion and decision making. Annual Review of Psychology 66: 799–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Tingting, Zhuanzhuan Wang, Anrun Zhu, Xi Zhang, and Cai Xing. 2022. The Effectiveness of Mating Induction on Men’s Financial Risk-Taking: Relationship Experience Matters. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 787686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, Andrew W., and Dmitry V. Repin. 2002. The psychophysiology of real-time financial risk processing. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience 14: 323–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maier, Steven F., and Martin E. P. Seligman. 2016. Learned helplessness at fifty: Insights from neuroscience. Psychological Review 123: 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, David, and Matthew Wilson. 2023. Effects of multiple discrete emotions on risk-taking propensity. Current Psychology 42: 15763–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, Michele J., and Janice M. Morse. 2015. Situating and constructing diversity in semi-structured interviews. Global Qualitative Nursing Research 2: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, Matthew B., and A. Michael Huberman. 2003. Analyse des données qualitatives. Bruxelles: De Boeck Supérieur. [Google Scholar]

- Naseem, Sobia, Muhammad Mohsin, Wang Hui, Geng Liyan, and Kun Penglai. 2021. The Investor Psychology and Stock Market Behavior During the Initial Era of COVID-19: A Study of China, Japan, and the United States. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 626934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowell, Lorelli S., Jill M. Norris, Deborah E. White, and Nancy J. Moules. 2017. Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwosu, Nelly T., and Oluwatosin Ilori. 2024. Behavioral finance and financial inclusion: A conceptual review and framework development. World Journal of Advanced Research and Reviews 22: 204–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opdenakker, R. J. G. 2006. Advantages and disadvantages of four interview techniques in qualitative research. In Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung = Forum: Qualitative Social Research. Dresden: Institut fur Klinische Sychologie and Gemeindesychologie, vol. 7, p. art-11. [Google Scholar]

- Padmavathy, M. 2024. Behavioral finance and stock market anomalies: Exploring psychological factors influencing investment decisions. Shanlax International Journal of Management 11: 191–97. Available online: https://storage.prod.researchhub.com/uploads/papers/2024/05/31/6438_odEUckg.pdf (accessed on 3 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Sánchez, Jennifer, and Ana R. Delgado. 2022. A metamethod study of qualitative research on emotion regulation strategies. Papeles del Psicólogo 43: 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pin, Clement. 2023. Semi-structured Interviews. LIEPP Methods Brief/Fiches méthodologiques du LIEPP. Available online: https://sciencespo.hal.science/hal-04087970/ (accessed on 14 December 2024).

- Porter, David P., and Vernon L. Smith. 2003. Stock market bubbles in the laboratory. The Journal of Behavioral Finance 4: 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosek, Elizabeth A., and Donna M. Gibson. 2021. Promoting Rigorous Research by Examining Lived Experiences: A Review of Four Qualitative Traditions. Journal of Counseling & Development 99: 167–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Jie. 2015. A model of regret, investor behavior, and market turbulence. Journal of Economic Theory 160: 150–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quoidbach, Jordi, Elizabeth V. Berry, Michel Hansenne, and Moïra Mikolajczak. 2010. Positive emotion regulation and well-being: Comparing the impact of eight savoring and dampening strategies. Personality and Individual Differences 49: 368–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raheja, Saloni, and Babli Dhiman. 2017. Influence of personality traits and behavioral biases on investment decision of investors. Asian Journal of Management 8: 819–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratner, Rebecca K., and Kenneth C. Herbst. 2005. When good decisions have bad outcomes: The impact of affect on switching behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 96: 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyna, Valerie F., and Frank Farley. 2006. Risk and rationality in adolescent decision making: Implications for theory, practice, and public policy. Psychological Science in the Public Interest 7: 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, Daniel W., Mark Fenton-O’Creevy, Janette Rutterford, and Devendra G. Kodwani. 2018. Is the disposition effect related to investors’ reliance on System 1 and System 2 processes or their strategy of emotion regulation? Journal of Economic Psychology 66: 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rick, Scott. 2011. Losses, gains, and brains: Neuroeconomics can help to answer open questions about loss aversion. Journal of Consumer Psychology 21: 453–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, Virginia. 2021. From theory to analysis: An introduction to using semi-structured individual interviews in political science. Revista: Politica Hoje 29: 226–51. [Google Scholar]

- Ruslin, Ruslin, Saepudin Mashuri, Muhammad Sarib Abdul Rasak, Firdiansyah Alhabsyi, and Hijrah Syam. 2022. Semi-structured Interview: A methodological reflection on the development of a qualitative research instrument in educational studies. IOSR Journal of Research & Method in Education (IOSR-JRME) 12: 22–29. Available online: http://repository.iainpalu.ac.id/id/eprint/1247/1/Saepudin%20Mashuri.%20Artkel%20inter..pdf (accessed on 14 June 2025).

- Serra, Daniel. 2017. Économie Comportementale. Paros: Economica. [Google Scholar]

- Severin, Marine I., Filip Raes, Evie Notebaert, Luka Lambrecht, Gert Everaert, and Ann Buysse. 2022. A qualitative study on emotions experienced at the coast and their influence on well-being. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 902122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shefrin, Hersh, and Meir Statman. 1985. The disposition to sell winners too early and ride losers too long: Theory and evidence. The Journal of Finance 40: 777–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Vernon L., Gerry L. Suchanek, and Arlington W. Williams. 1988. Bubbles, crashes, and endogenous expectations in experimental spot asset markets. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society 56: 1119–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smulowitz, Stacy. 2017. Interview guide. In The International Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods. Hoboken: Wiley, pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strahilevitz, Michal Ann, Terrance Odean, and Brad M. Barber. 2011. Once burned, twice shy: How naive learning, counterfactuals, and regret affect the repurchase of stocks previously sold. Journal of Marketing Research 48: S102–S120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summers, Barbara, and Darren Duxbury. 2012. Decision-dependent emotions and behavioral anomalies. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 118: 226–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, Samuel. 2007. The Effect of Pride and Regret on Investors’ Trading Behavior. Available online: https://repository.upenn.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/b3e67a01-8296-496e-ab07-921be302c13c/content (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Troy, Allison S., Amanda J. Shallcross, and Iris B. Mauss. 2013. A person-by-situation approach to emotion regulation: Cognitive reappraisal can either help or hurt, depending on the context. Psychological Science 24: 2505–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsalatsanis, Athanasios, Iztok Hozo, Andrew Vickers, and Benjamin Djulbegovic. 2010. A regret theory approach to decision curve analysis: A novel method for eliciting decision makers’ preferences and decision-making. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making 10: 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tversky, Amos, and Daniel Kahneman. 1974. Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases: Biases in judgments reveal some heuristics of thinking under uncertainty. Science 185: 1124–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Dijk, Eric, and Marcel Zeelenberg. 2005. On the psychology of ‘if only’: Regret and the comparison between factual and counterfactual outcomes. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 97: 152–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dijk, Wilco W., and Joop Van der Pligt. 1997. The impact of probability and magnitude of outcome on disappointment and elation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 69: 277–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vears, Danya F., and Lynn Gillam. 2022. Inductive content analysis: A guide for beginning qualitative researchers. Focus on Health Professional Education: A Multi-Professional Journal 23: 111–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, Cynthia, and Émilie Tremblay-Wragg. 2021. L’observation participante d’un terrain de recherche: Une avenue pour discerner ses intérêts et questions de recherche. McGill Journal of Education 56: 234–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, Richard M., Oliver James, and Gene A. Brewer. 2017. Replication, experiments and knowledge in public management research. Public Management Review 19: 1221–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Haocheng, Jian Zhang, Limin Wang, and Shuyi Liu. 2014. Emotion and investment returns: Situation and personality as moderators in a stock market. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal 42: 561–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeelenberg, Marcel, and Rik Pieters. 2007. A theory of regret regulation 1.0. Journal of Consumer Psychology 17: 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).