Hyperbolic Discounting and Its Influence on Loss Tolerance: Evidence from Japanese Investors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Data

3.2. Variables

3.2.1. Dependent Variable

3.2.2. Independent Variables

3.3. Descriptive Statistics

3.4. Empirical Model

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Main Results

4.2. Robustness Checks

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DR1 | Discount rate 1 |

| DR2 | Discount rate 2 |

| VIF | Variance Inflation Factor |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Intertemporal Questions

| Scenario One: You were given a certain amount of money. You can get it after two or nine days, but the amount will be different. If you had option A or B for the date and amount you would receive, which one would you choose? Choose whichever combination you like from 1 to 8 (only one of each). | ||

| Question 1 | Option A | Option B |

| Combination 1: | You will receive 10,000 yen in two days. | After nine days, you will receive 9981 yen. |

| Combination 2: | You will receive 10,000 yen in two days. | After nine days, you will receive 10,000 yen. |

| Combination 3: | You will receive 10,000 yen in two days. | After nine days, you will receive 10,019 yen. |

| Combination 4: | You will receive 10,000 yen in two days. | After nine days, you will receive 10,038 yen. |

| Combination 5: | You will receive 10,000 yen in two days. | After nine days, you will receive 10,096 yen. |

| Combination 6: | You will receive 10,000 yen in two days. | After nine days, you will receive 10,191 yen. |

| Combination 7: | You will receive 10,000 yen in two days. | After nine days, you will receive 10,383 yen. |

| Combination 8: | You will receive 10,000 yen in two days. | After nine days, you will receive 10,574 yen. |

| Scenario two: You were given a certain amount of money. You can get it after 90 or 97 days, but the amount will be different. If you had option A or B for the date and amount you would receive, which one would you choose? For combinations from 1 to 9, choose whichever you like and mark it with a circle. | ||

| Question 2 | Option A | Option B |

| Combination 1: | After 90 days, you will receive 10,000 yen. | After 97 days, you will receive 9981 yen. |

| Combination 2: | After 90 days, you will receive 10,000 yen. | After 97 days, you will receive 10,000 yen. |

| Combination 3: | After 90 days, you will receive 10,000 yen. | After 97 days, you will receive 10,019 yen. |

| Combination 4: | After 90 days, you will receive 10,000 yen. | After 97 days, you will receive 10,038 yen. |

| Combination 5: | After 90 days, you will receive 10,000 yen. | After 97 days, you will receive 10,096 yen. |

| Combination 6: | After 90 days, you will receive 10,000 yen. | After 97 days, you will receive 10,191 yen. |

| Combination 7: | After 90 days, you will receive 10,000 yen. | After 97 days, you will receive 10,383 yen. |

| Combination 8: | After 90 days, you will receive 10,000 yen. | After 97 days, you will receive 10,574 yen. |

Appendix A.2. Mean and Standard Deviation of Variables Before and After Excluding Missing Values

| Variable | Mean | Std. Dev. | ||||

| Before | After | Diff | Before | After | Diff | |

| Loss tolerance | 0.242 | 0.248 | −2.5% | 0.129 | 0.127 | 1.6% |

| Loss tolerance Binary | 0.463 | 0.482 | −4.1% | 0.499 | 0.5 | −0.2% |

| Hyperbolic Discounting | 0.145 | 0.144 | 0.7% | 0.558 | 0.528 | 5.4% |

| Gender (Male = 1) | 0.608 | 0.643 | −5.8% | 0.488 | 0.479 | 1.8% |

| Age | 44.514 | 45.019 | −1.1% | 12.051 | 11.889 | 1.3% |

| Married status (Married = 1) | 0.635 | 0.662 | −4.3% | 0.481 | 0.473 | 1.7% |

| Children | 1.027 | 1.088 | −5.9% | 1.098 | 1.104 | −0.5% |

| Years of Education | 15.146 | 15.195 | −0.3% | 2.066 | 2.057 | 0.4% |

| Full-time Job | 0.68 | 0.706 | −3.8% | 0.466 | 0.456 | 2.1% |

| Household Income | 763,2059.6 | 7,762,545 | −1.7% | 4,250,795.5 | 4,253,144.9 | −0.1% |

| Household Asset | 20,961,856 | 21,496,228 | −2.5% | 25,080,491 | 25,354,522 | −1.1% |

| RiskAversion | 0.538 | 0.535 | 0.6% | 0.234 | 0.235 | −0.4% |

| MyopicView | 0.147 | 0.148 | −0.7% | 0.354 | 0.355 | −0.3% |

References

- Andersen, Steffen, Glenn W. Harrison, Morten I. Lau, and E. Elisabet Rutström. 2008. Eliciting risk and time preferences. Econometrica 76: 583–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeletos, Marios, David Laibson, Andrea Repetto, Jeremy Tobacman, and Stephen Weinberg. 2000. Hyperbolic Discounting, Wealth Accumulation, and Consumption. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/p/edj/ceauch/90.html (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Barberis, Nicholas, Andrei Shleifer, and Robert Vishny. 1998. A Model of investor sentiment. Journal of Financial Economics 49: 307–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bawalle, Aliyu Ali, Sumeet Lal, Trinh Xuan Thi Nguyen, Mostafa Saidur Rahim Khan, and Yoshihiko Kadoya. 2024. Navigating time-inconsistent behavior: The influence of financial knowledge, behavior, and attitude on hyperbolic discounting. Behavioral Sciences 14: 994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benartzi, Shlomo, and Richard H. Thaler. 1995. Myopic loss aversion and the equity premium puzzle. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 110: 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, Robson, and Luiz Paulo Lopes Fávero. 2017. Disposition effect and tolerance to losses in stock investment decisions: An experimental study. Journal of Behavioral Finance 18: 271–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavatorta, Elisa, and Ben Groom. 2019. Hyperbolic Discounting in the Absence of Credibility. Available online: https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/working-paper-319-Cavatorta-Groom-1.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Chen, Haipeng (Allan), Sharon Ng, and Akshay R. Rao. 2005. Cultural differences in consumer impatience. Journal of Marketing Research 42: 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitenderu, Tafadzwa T., Andrew Maredza, and Kin Sibanda. 2014. The random walk theory and stock prices: Evidence from the Johannesburg stock exchange. International Business & Economics Research Journal 13: 1241–50. [Google Scholar]

- Dayani, Amir, and Setareh Jannati. 2022. Running a mutual fund: Performance and trading behavior of runner managers. Journal of Empirical Finance 69: 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epper, Thomas, and Helga Fehr-Duda. 2023. Risk in time: The intertwined nature of risk taking and time discounting. Journal of the European Economic Association 21: 1407–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gathergood, Johm, Neale Mahoney, Neil Stewart, and Jorg Weber. 2019. How do individuals repay their debt? The balance-matching heuristic. American Economic Review 109: 844–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, Christopher, and David Laibson. 2001. Dynamic Choices of Hyperbolic Discounting. Econometrica 69: 935–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellmann, Thomas, Alexander Montag, and Joacim Tåg. 2024. Tolerating Losses for Growth: J-Curves in Venture Capital Investing. IFN Working Paper No. 1500. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4937026 (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Hofstede, Geert. 2001. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions and Organizations Across Nations. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Homma, Daiki, Takaaki Fukazawa, Mostafa Saidur Rahim Khan, and Yoshihiko Kadoya. 2025. Beyond knowledge: The impact of financial attitude and behavior on panic selling during market crises. Cogent Economics & Finance 13: 2476090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Harrison, Jeffrey D. Kubik, and Jeremy C. Stein. 2004. Social interaction and stock-market participation. The Journal of Finance 59: 137–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, Shinsuke. 2016. Hyperbolic discounting and self-destructive behaviors. In The Economic of Self-Destructive Choices. Tokyo: Springer, pp. 43–65. [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda, Shinsuke, and Miho I. Kang. 2015. Hyperbolic discounting, borrowing aversion and debt holding. The Japanese Economic Review 66: 421–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, Daniel, and Amos Tversky. 1979. Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica 47: 263–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamesaka, Akiko, John R. Nofsinger, and Hideaki Kawakita. 2003. Investment patterns and performance of investor groups in Japan. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal 11: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Myong-Il, and Shinsuke Ikeda. 2014. Time discounting and smoking behavior: Evidence from a panel survey. Health Economics 23: 1443–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katauke, Takuya, Sayaka Fukuda, Mostafa Saidur, Rahim Khan, and Yoshihiko Kadoya. 2023. Financial literacy and impulsivity: Evidence from Japan. Sustainability 15: 7267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Bokyung, Young Shin Sung, and Samuel M. McClure. 2012. The neural basis of cultural differences in delay discounting. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 367: 650–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitayama, Shinobu, and Yukiko Uchida. 2005. Interdependent agency: An alternative system for action. In Culture and Social Behavior: The Ontario Symposium. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum, vol. 10, pp. 137–64. [Google Scholar]

- Laibson, David. 1997. Golden eggs and hyperbolic discounting. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 112: 443–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, Sumeet, Trinh Xuan Thi Nguyen, Aliyu Ali Bawalle, Mostafa Saidur Rahim Khan, and Yoshihiko Kadoya. 2024. Unraveling investor behavior: The role of hyperbolic discounting in panic selling behavior on the global COVID-19 financial crisis. Behavioral Sciences 14: 795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lusardi, Annamaria, and Olivia S. Mitchell. 2014. The economic importance of financial literacy: Theory and evidence. Journal of Economic Literature 52: 5–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madrian, Brigitte C., and Dennis F. Shea. 2001. The power of suggestion: Inertia in 401(k) participation and savings behavior. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 116: 1149–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, Ahlbrecht, and Martin Weber. 1995. Hyperbolic discounting models in prescriptive theory of intertemporal choice. Journal of Contextual Economics–Schmollers Jahrbuch 115: 535–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, Andrew, Naohiro Ogawa, and Takashi Fukui. 2010. Ageing, family support systems, saving and wealth: Is decline on the horizon for Japan? In Ageing in Advanced Industrial States. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 139–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClure, Samuel M., David I. Laibson, George Loewenstein, and Jonathan D. Cohen. 2004. Separate neural systems value immediate and delayed monetary rewards. Science 306: 503–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, Stephan, and Charles D. Sprenger. 2015. Temporal stability of time preferences. Review of Economics and Statistics 97: 273–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, Stephan, and Charles Sprenger. 2010. Present-biased preferences and credit card borrowing. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 2: 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabeshima, Hiroshi, Sumeet Lal, Haruka Izumi, Yuzuha Himeno, Mostafa Saidur, Rahim Khan, and Yoshihiko Kadoya. 2025. The impact of hyperbolic discounting on asset accumulation for later life: A study of active investors aged 65 years and over in Japan. Risks 13: 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odean, Terrance. 1998. Are investors reluctant to realize their losses? The Journal of Finance 53: 1775–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donoghue, Ted, and Matthew Rabin. 1999. Doing it now or later. American Economic Review 89: 103–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ormos, Mihály, and István Joó. 2014. Are Hungarian investors reluctant to realize their losses? Economic Modelling 40: 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachlin, Howard, and Andres Raineri. 1992. Irrationality, Impulsiveness, and Selfishness as Discount Reversal Effects. Choice over Time. Available online: https://books.google.co.jp/books?hl=ja&lr=lang_jalang_en&id=8_MWAwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA93&dq=Irrationality,+impulsiveness,+and+selfishness+as+discount+reversal+effects&ots=x5LF2kChRv&sig=Mn5hMaNq0p-PevZ9S0YIoEhXKXE#v=onepage&q=Irrationality%2C%20impulsiveness%2C%20and%20selfishness%20as%20discount%20reversal%20effects&f=false (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Ring, Patric, Catharina C. Probst, Levent Neyse, Stephan Wolff, Christian Kaernbach, Thilo van Eimeren, and Ulrich Schmidt. 2022. Discounting behavior in problem gambling. Journal of Gambling Studies 38: 529–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seru, Amit, Tyler Shumway, and Noah Stoffman. 2010. Learning by trading. The Review of Financial Studies 23: 705–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shefrin, Hersh, and Meir Statman. 1985. The disposition to sell winners too early and ride losers too long: Theory and evidence. The Journal of Finance 40: 777–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoji, Isao, and Shigeo Kanehiro. 2012. Intertemporal dynamic choice under myopia for reward and different risk tolerances. Economic Theory 50: 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, Taiki. 2007. A comparison of intertemporal choices for oneself versus someone else based on Tsallis’ statistics. Physica A 385: 637–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, Taiki, Tarik Hadzibeganovic, Sergio Cannas, Takaki Makino, Hiroki Fukui, and Shinobu Kitayama. 2009. Cultural neuroeconomics of intertemporal choice. Neuro Endocrinology Letters 30: 185–91. [Google Scholar]

- Takemura, Kazuhisa. 2020. Behavioral Decision Theory. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. Available online: https://oxfordre.com/politics/display/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228637-e-958 (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Tanaka, Saori C., Katsunori Yamada, Hiroyasu Yoneda, and Fumio Ohtake. 2014. Neural mechanisms of gain-loss asymmetry in temporal discounting. Journal of Neuroscience 34: 5595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasoff, Joshua, and Wataru Zhang. 2020. The Performance of Time-Preference and Risk-Preference Measures in Surveys. SSRN Working Paper. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3165792 (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Wang, Mei, Marc Oliver Rieger, and Thorsten Hens. 2016. How time preferences differ: Evidence from 53 countries. Journal of Economic Psychology 52: 115–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, Elke U., Ann-Renée Blais, and Nancy E. Betz. 2002. A domain-specific risk-attitude scale: Measuring risk perceptions and risk behaviors. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making 15: 263–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Lin. 2013. Saving and retirement behavior under quasi-hyperbolic discounting. Journal of Economics 109: 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Lin. 2016. Empirical Evidence of Hyperbolic Discounting in China. The Journal of Kanazawa Seiryo University 49: 89–98. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Definition |

|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | |

| Investment loss tolerance | Discrete variable: How much loss respondents can withstand if they invest JPY 1 million in an investment trust (1%/10%/20%/30%/40% loss) |

| Investment loss tolerance dummy | Binary variable: 1 = respondents can withstand a loss of 30% or more if they invest JPY 1 million in an investment trust |

| Independent Variable | |

| Hyperbolic discounting | Binary variable: 1 = respondents’ DR1 exceeds DR2, 0 = otherwise |

| Gender | Binary variable: 1 = male, 0 = female |

| Age | Continuous variable: Respondents’ age |

| Age squared | Continuous variable: Squared of respondents’ age |

| Marital status | Binary variable: 1 = having a spouse, 0 = otherwise |

| Number of children | Continuous variable: Number of children |

| Education year | Continuous variable: Years of education |

| Having a job | Binary variable: 1 = having a full time job, 0 = otherwise |

| Household income | Continuous variable: Total annual income, including tax, for the household in 2024 in Japanese Yen |

| Household assets | Continuous variable: Total household balance of financial assets in 2024 in Japanese Yen |

| Risk aversion | Continuous variable: A measure of respondents’ risk aversion (the answer to the following question: When you usually go out with an umbrella, what is the probability of rain?) |

| Myopic view of the future | Binary variable: 1 if the respondent agrees that the future is uncertain and there is no point in thinking about it, and 0 otherwise. |

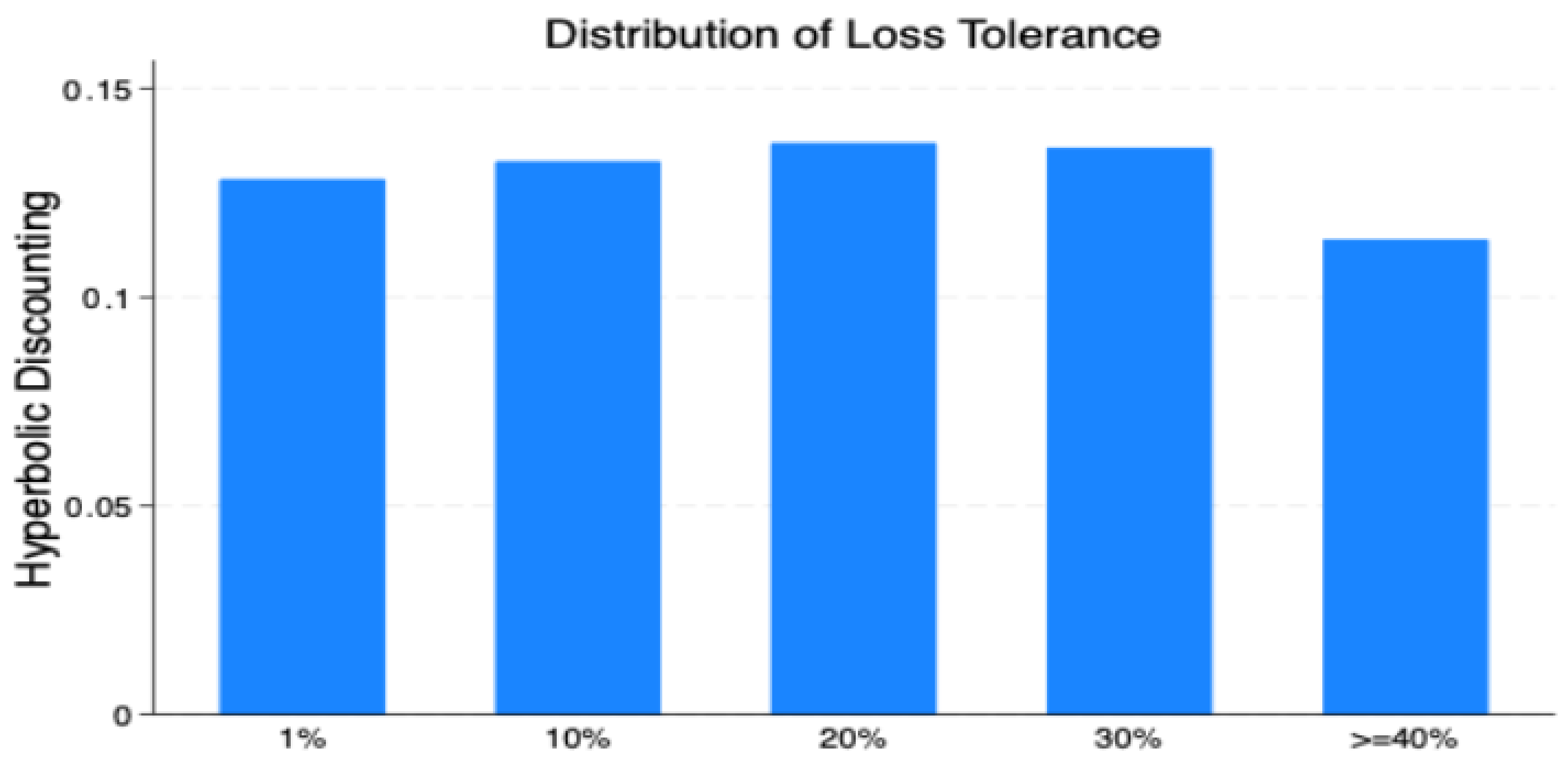

| Variable | Mean (or %) | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | ||||

| Loss Tolerance | 24.8% | |||

| 1% | 4.50% | |||

| 10% | 23.7% | |||

| 20% | 23.6% | |||

| 30% | 15.8% | |||

| ≥40% | 32.4% | |||

| Independent Variables | ||||

| Hyperbolic Discounting | 12.80% | |||

| Gender (Male = 1) | 64.3% | |||

| Age | 45.019 | 11.889 | 18 | 90 |

| Age Squared | 2168 | 1117 | 324 | 8100 |

| Age Group | ||||

| 18–39 | 35.90% | |||

| 40–65 | 59.3% | |||

| >65 | 4.80% | |||

| Marital Status (Married = 1) | 66.20% | |||

| Children | 1.088 | 1.104 | 0 | 12 |

| Years of Education | 15.195 | 2.057 | 9 | 21 |

| Full-time Job | 70.60% | |||

| Annual Income in 2024 | 7,762,545 | 4,253,144.9 | 1,000,000 | 20,000,000 |

| Household Financial Assets in 2024 | 21,496,228 | 25,354,522 | 2,500,000 | 100,000,000 |

| Household Asset Group | ||||

| Low Household Asset | 60.50% | |||

| High Household Asset | 39.50% | |||

| Natural Log of Annual Income | 15.701 | 0.611 | 13.816 | 16.811 |

| Natural Log of Household Assets | 16.277 | 1.104 | 14.732 | 18.421 |

| Risk Aversion | 53.50% | |||

| Myopic View of the Future | 14.80% | |||

| Number of Observations: 107,294 | ||||

| Loss Tolerance | Gender | Age Group | Asset Group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females | Male | 18–39 | 40–65 | >65 | Low | High | Total | |

| 1% | 2853 | 2004 | 1915 | 2724 | 218 | 3820 | 1037 | 4857 |

| 58.74 | 41.26 | 39.43 | 56.08 | 4.49 | 78.65 | 21.35 | 100.00 | |

| 7.44 | 2.91 | 4.97 | 4.28 | 4.26 | 5.89 | 2.45 | 4.53 | |

| 10% | 11,241 | 14195 | 9008 | 14,893 | 1535 | 18,079 | 7357 | 25,436 |

| 44.19 | 55.81 | 35.41 | 58.55 | 6.03 | 71.08 | 28.92 | 100.00 | |

| 29.31 | 20.59 | 23.39 | 23.39 | 29.99 | 27.86 | 17.35 | 23.71 | |

| 20% | 9014 | 16,267 | 8677 | 15,077 | 1527 | 15,713 | 9568 | 25,281 |

| 35.66 | 64.34 | 34.32 | 59.64 | 6.04 | 62.15 | 37.85 | 100.00 | |

| 23.50 | 23.60 | 22.53 | 23.68 | 29.84 | 24.22 | 22.56 | 23.56 | |

| 30% | 5797 | 11,164 | 5800 | 10,296 | 865 | 9490 | 7471 | 16,961 |

| 34.18 | 65.82 | 34.20 | 60.70 | 5.10 | 55.95 | 44.05 | 100.00 | |

| 15.11 | 16.19 | 15.06 | 16.17 | 16.90 | 14.63 | 17.61 | 15.81 | |

| ≥40% | 9450 | 25,309 | 13,105 | 20,681 | 973 | 17,779 | 16,980 | 34,759 |

| 27.19 | 72.81 | 37.70 | 59.50 | 2.80 | 51.15 | 48.85 | 100.00 | |

| 24.64 | 36.71 | 34.03 | 32.48 | 19.01 | 27.40 | 40.03 | 32.40 | |

| Total | 38,355 | 68,939 | 38,505 | 63,671 | 5118 | 64,881 | 42,413 | 107,294 |

| 35.75 | 64.25 | 35.89 | 59.34 | 4.77 | 60.47 | 39.53 | 100.00 | |

| 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | |

| Pearson Chi2 = 3035.05 Prob = 0.0000 | Pearson Chi2 = 556.90 Prob = 0.0000 | Pearson Chi2 = 3306.68 Prob = 0.0000 | ||||||

| Dependent Variable: Investment Loss Tolerance (Categorical: 1–40%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 Coef. (SE) | Model 2 Coef. (SE) | Model 3 Coef. (SE) | Marginal Effect (Model 3) | |

| Hyperbolic Discounting | −0.07 *** | −0.063 *** | −0.063 *** | −0.070 *** |

| (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | ||

| Gender | 0.382 *** | 0.387 *** | 0.388 *** | 0.435 *** |

| (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.007) | ||

| Age | 0.043 *** | 0.029 *** | 0.029 *** | 0.033 *** |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | ||

| Age Squared | 0.000 *** | 0.000 *** | 0.000 *** | −0.001 *** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | ||

| Marital Status | −0.04 *** | −0.101 *** | −0.102 *** | −0.113 *** |

| (0.008) | (0.009) | (0.009) | ||

| Children | −0.035 *** | −0.015 *** | −0.016 *** | −0.019 *** |

| (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.004) | ||

| Education | 0.022 *** | −0.01 *** | −0.01 *** | −0.012 *** |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | ||

| Full-time Job | 0.024 *** | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.012 *** |

| (0.008) | (0.009) | (0.009) | ||

| Natural Log of Annual Income | 0.007 | 0.008 | 0.005 *** | |

| (0.007) | (0.007) | |||

| Natural Log of Household Assets | 0.255 *** | 0.257 *** | 0.286 *** | |

| (0.004) | (0.004) | |||

| Risk Aversion | −0.091 *** | −0.113 *** | ||

| (0.015) | ||||

| Myopic View of the Future | −0.01 | −0.056 *** | ||

| (0.009) | ||||

| /cut1 | −0.376 *** | 2.824 *** | 2.802 *** | |

| (0.051) | (0.104) | (0.105) | ||

| /cut2 | 0.768 *** | 4.002 *** | 3.981 *** | |

| (0.05) | (0.105) | (0.105) | ||

| /cut3 | 1.404 *** | 4.659 *** | 4.639 *** | |

| (0.051) | (0.105) | (0.105) | ||

| /cut4 | 1.825 *** | 5.094 *** | 5.074 *** | |

| (0.051) | (0.105) | (0.105) | ||

| Observations | 107,294 | 107,294 | 107,294 | |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.014 | 0.032 | 0.032 | |

| Dependent Variable: Investment Loss Tolerance (Ordered Probit) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male Coef. (SE) | Female Coef. (SE) | 18–39 Coef. (SE) | 40–65 Coef. (SE) | >65 Coef. (SE) | Low Assets Coef. (SE) | High Assets Coef. (SE) | |

| Hyperbolic Discounting | −0.084 *** | −0.021 | −0.078 *** | −0.053 *** | −0.069 * | −0.055 *** | −0.076 *** |

| (0.012) | (0.017) | (0.017) | (0.012) | (0.038) | (0.012) | (0.015) | |

| Gender | 0.438 *** | 0.367 *** | 0.186 *** | 0.418 *** | 0.338 *** | ||

| (0.012) | (0.01) | (0.043) | (0.009) | (0.013) | |||

| Age | 0.024 *** | 0.029 *** | 0.073 *** | 0.032 *** | −0.096 | 0.021 *** | 0.021 *** |

| (0.002) | (0.003) | (0.016) | (0.009) | (0.123) | (0.003) | (0.004) | |

| Age Squared | 0.000 *** | 0 *** | −0.001 *** | 0.000 *** | 0.000 | 0.000 *** | 0.000 *** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.001) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Marital Status | −0.109 *** | −0.075 *** | −0.07 *** | −0.125 *** | −0.12 *** | −0.115 *** | −0.092 *** |

| (0.012) | (0.015) | (0.015) | (0.012) | (0.044) | (0.011) | (0.015) | |

| Children | −0.006 | −0.032 *** | −0.022 *** | −0.015 *** | −0.011 | −0.025 *** | −0.004 |

| (0.005) | (0.006) | (0.008) | (0.004) | (0.016) | (0.005) | (0.006) | |

| Education | −0.013 *** | 0.002 | −0.002 | −0.012 *** | −0.007 | −0.008 *** | −0.011 *** |

| (0.002) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.002) | (0.008) | (0.002) | (0.003) | |

| Full-time Job | −0.002 | 0.029 ** | 0.028 * | 0.000 | 0.013 | −0.018 | 0.043 *** |

| (0.013) | (0.013) | (0.016) | (0.011) | (0.048) | (0.011) | (0.014) | |

| Natural Log Income | −0.005 | 0.021 * | 0.011 | 0.002 | 0.046 | 0.036 *** | −0.039 *** |

| (0.009) | (0.012) | (0.014) | (0.009) | (0.03) | (0.01) | (0.011) | |

| Natural Log of Household Assets | 0.254 *** | 0.262 *** | 0.287 *** | 0.25 *** | 0.203 *** | 0.296 *** | 0.235 *** |

| (0.004) | (0.006) | (0.007) | (0.005) | (0.016) | (0.008) | (0.01) | |

| Risk Aversion | −0.132 *** | −0.007 | −0.106 *** | −0.081 *** | −0.104 | −0.108 *** | −0.065 *** |

| (0.018) | (0.026) | (0.025) | (0.019) | (0.073) | (0.019) | (0.024) | |

| Myopic View of the Future | 0.003 | −0.031 ** | −0.01 | −0.017 | 0.044 | −0.006 | −0.019 |

| (0.012) | (0.015) | (0.015) | (0.013) | (0.05) | (0.012) | (0.016) | |

| /cut1 | 1.891 *** | 3.486 *** | 4.241 *** | 2.579 *** | −2.072 | 3.75 *** | 1.395 *** |

| (0.134) | (0.172) | (0.305) | (0.264) | (4.423) | (0.164) | (0.212) | |

| /cut2 | 3.108 *** | 4.631 *** | 5.379 *** | 3.768 *** | −0.704 | 4.942 *** | 2.551 *** |

| (0.134) | (0.173) | (0.305) | (0.264) | (4.423) | (0.164) | (0.212) | |

| /cut3 | 3.788 *** | 5.253 *** | 6.012 *** | 4.43 *** | 0.089 | 5.587 *** | 3.234 *** |

| (0.134) | (0.173) | (0.306) | (0.264) | (4.423) | (0.164) | (0.212) | |

| /cut4 | 4.22 *** | 5.696 *** | 6.426 *** | 4.873 *** | 0.62 | 6.002 *** | 3.698 *** |

| (0.134) | (0.173) | (0.306) | (0.264) | (4.423) | (0.164) | (0.212) | |

| Observations | 68,939 | 38,355 | 38,505 | 63,671 | 5,118 | 64,881 | 42,413 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.026 | 0.021 | 0.036 | 0.031 | 0.02 | 0.023 | 0.024 |

| Dependent Variable: Investment Loss Tolerance (Binary, ≥30% Loss) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 4 Coef. (SE) | Model 5 Coef. (SE) | Model 6 Coef. (SE) | |

| Hyperbolic Discounting | −0.074 *** | −0.067 *** | −0.065 *** |

| (0.012) | (0.012) | (0.012) | |

| Gender | 0.353 *** | 0.356 *** | 0.351 *** |

| (0.009) | (0.009) | (0.009) | |

| Age | 0.048 *** | 0.035 *** | 0.035 *** |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | |

| Age Squared | −0.001 *** | −0.001 *** | −0.001 *** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Marital Status | −0.051 *** | −0.103 *** | −0.105 *** |

| (0.01) | (0.011) | (0.011) | |

| Children | −0.042 *** | −0.02 *** | −0.022 *** |

| (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.004) | |

| Education | 0.016 *** | −0.017 *** | −0.017 *** |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | |

| Full-time Job | 0.015 | 0.009 | 0.01 |

| (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | |

| Natural Log of Annual Income | −0.016 * | −0.018 ** | |

| (0.009) | (0.009) | ||

| Natural Log of Household Assets | 0.272 *** | 0.27 *** | |

| (0.004) | (0.004) | ||

| Risk Aversion | −0.096 *** | ||

| (0.017) | |||

| Myopic View of the Future | −0.053 *** | ||

| (0.004) | |||

| _Cons | −1.386 *** | −4.514 *** | −4.28 *** |

| (0.06) | (0.123) | (0.124) | |

| Observations | 107,294 | 107,294 | 107,294 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.02 | 0.051 | 0.052 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kuramoto, Y.; Bawalle, A.A.; Khan, M.S.R.; Kadoya, Y. Hyperbolic Discounting and Its Influence on Loss Tolerance: Evidence from Japanese Investors. Risks 2025, 13, 202. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks13100202

Kuramoto Y, Bawalle AA, Khan MSR, Kadoya Y. Hyperbolic Discounting and Its Influence on Loss Tolerance: Evidence from Japanese Investors. Risks. 2025; 13(10):202. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks13100202

Chicago/Turabian StyleKuramoto, Yu, Aliyu Ali Bawalle, Mostafa Saidur Rahim Khan, and Yoshihiko Kadoya. 2025. "Hyperbolic Discounting and Its Influence on Loss Tolerance: Evidence from Japanese Investors" Risks 13, no. 10: 202. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks13100202

APA StyleKuramoto, Y., Bawalle, A. A., Khan, M. S. R., & Kadoya, Y. (2025). Hyperbolic Discounting and Its Influence on Loss Tolerance: Evidence from Japanese Investors. Risks, 13(10), 202. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks13100202