Emerging Risks in the Fintech-Driven Digital Banking Environment: A Bibliometric Review of China and India

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Literature

2.1.1. Institutional Theory

2.1.2. Asymmetric Information Theory

2.1.3. Holistic Digital Maturity Model (HDMM)

2.2. Banking Evolution and Integration with Information Communication Technologies (ICT)

2.3. Emerging Risks

2.3.1. Cybersecurity and Data Privacy Risks

2.3.2. Regulatory and Compliance Risk

2.3.3. Operational Risk

2.3.4. Ethical and Societal Risks

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Performance Analysis

3.1.1. Publication Trend

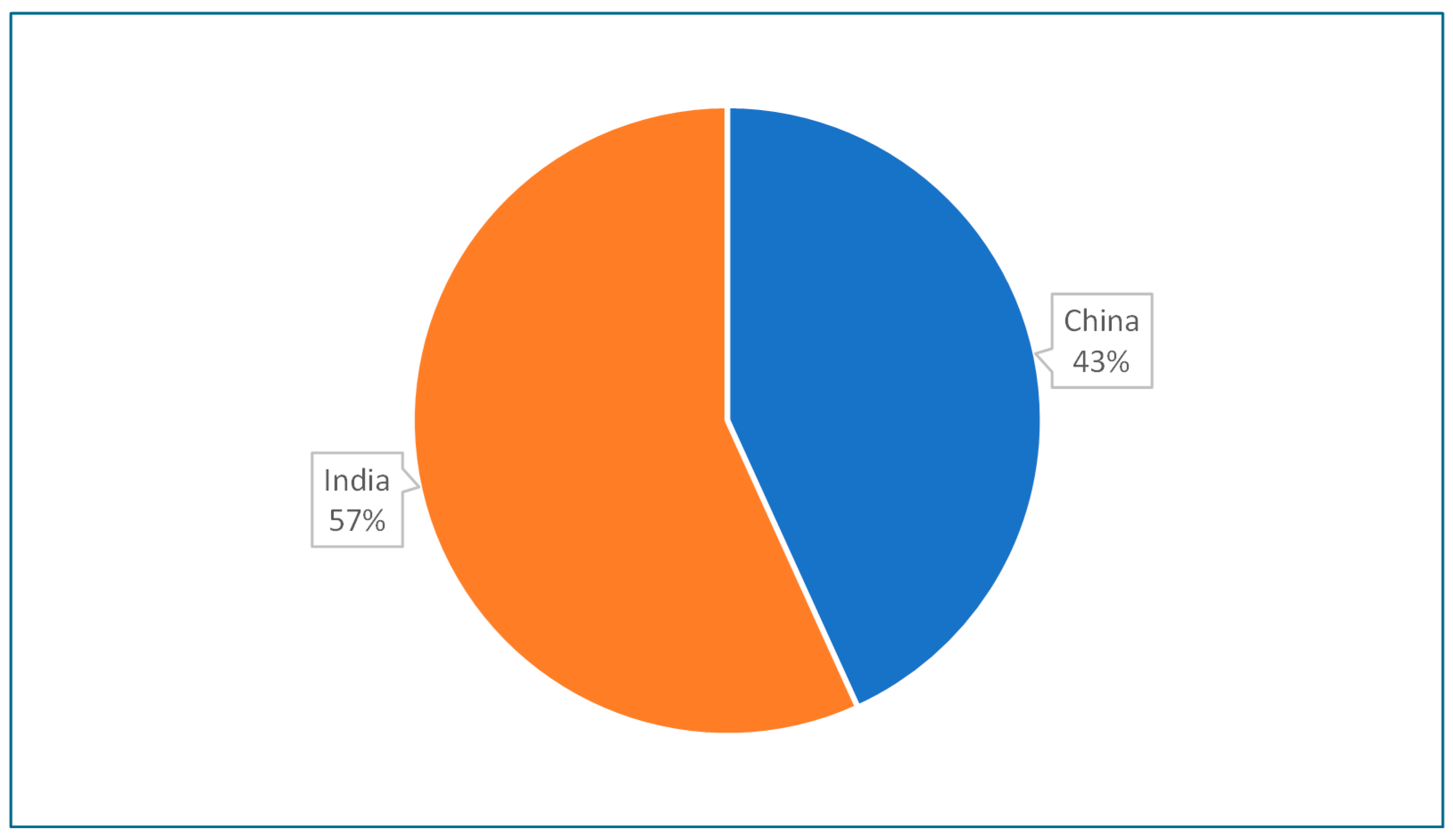

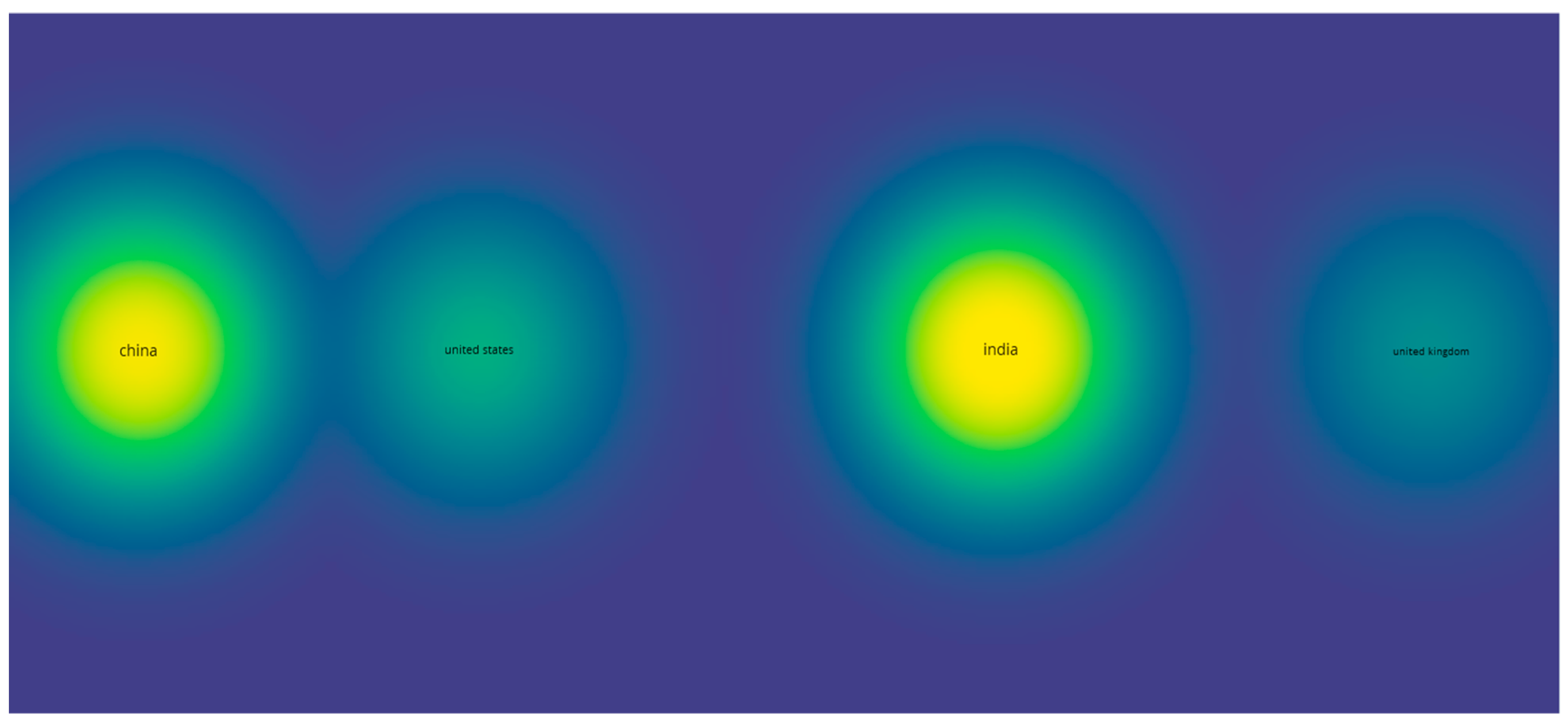

3.1.2. Research Output by Country and Institutional Contributions

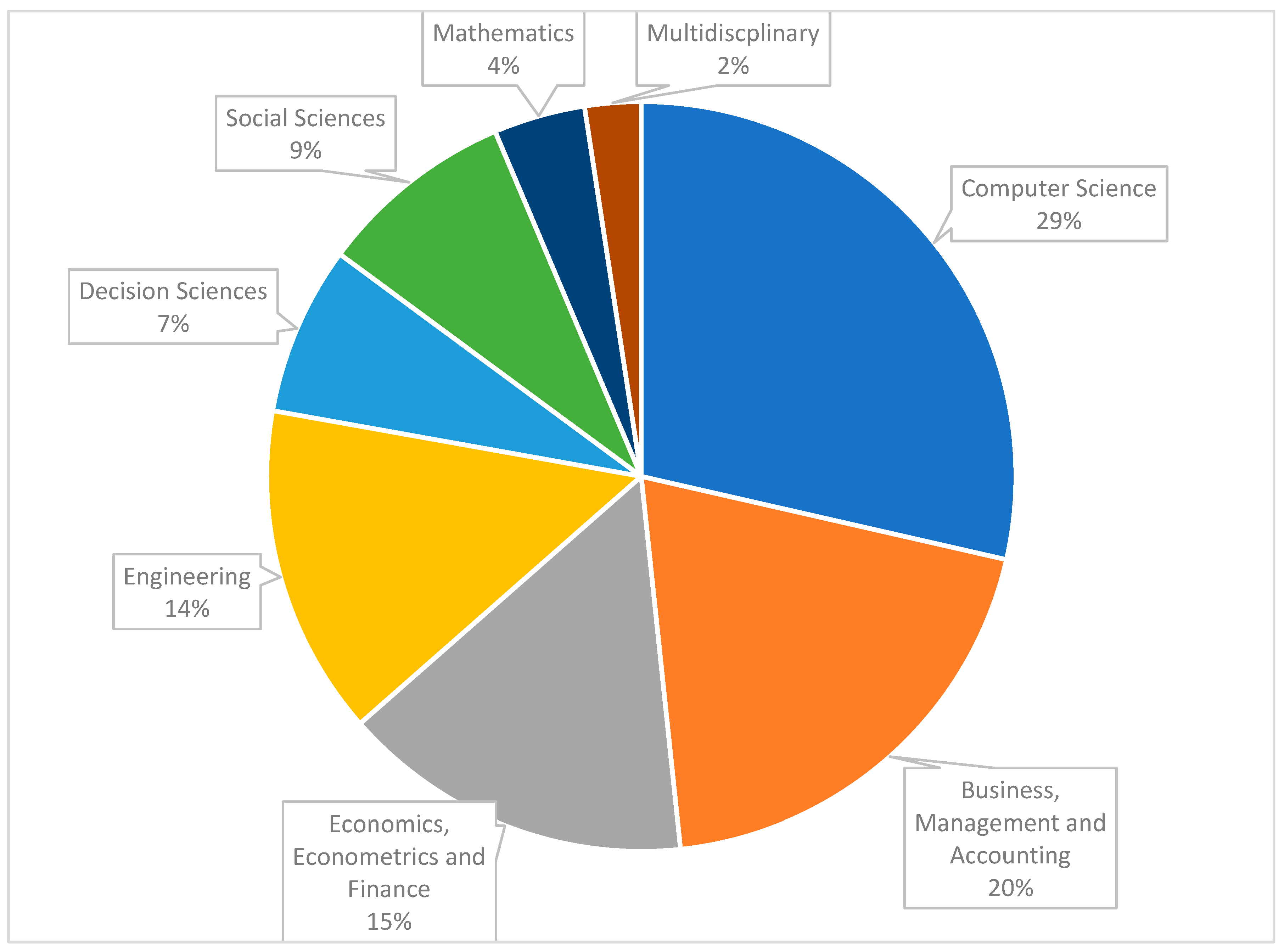

3.1.3. Publication by Discipline

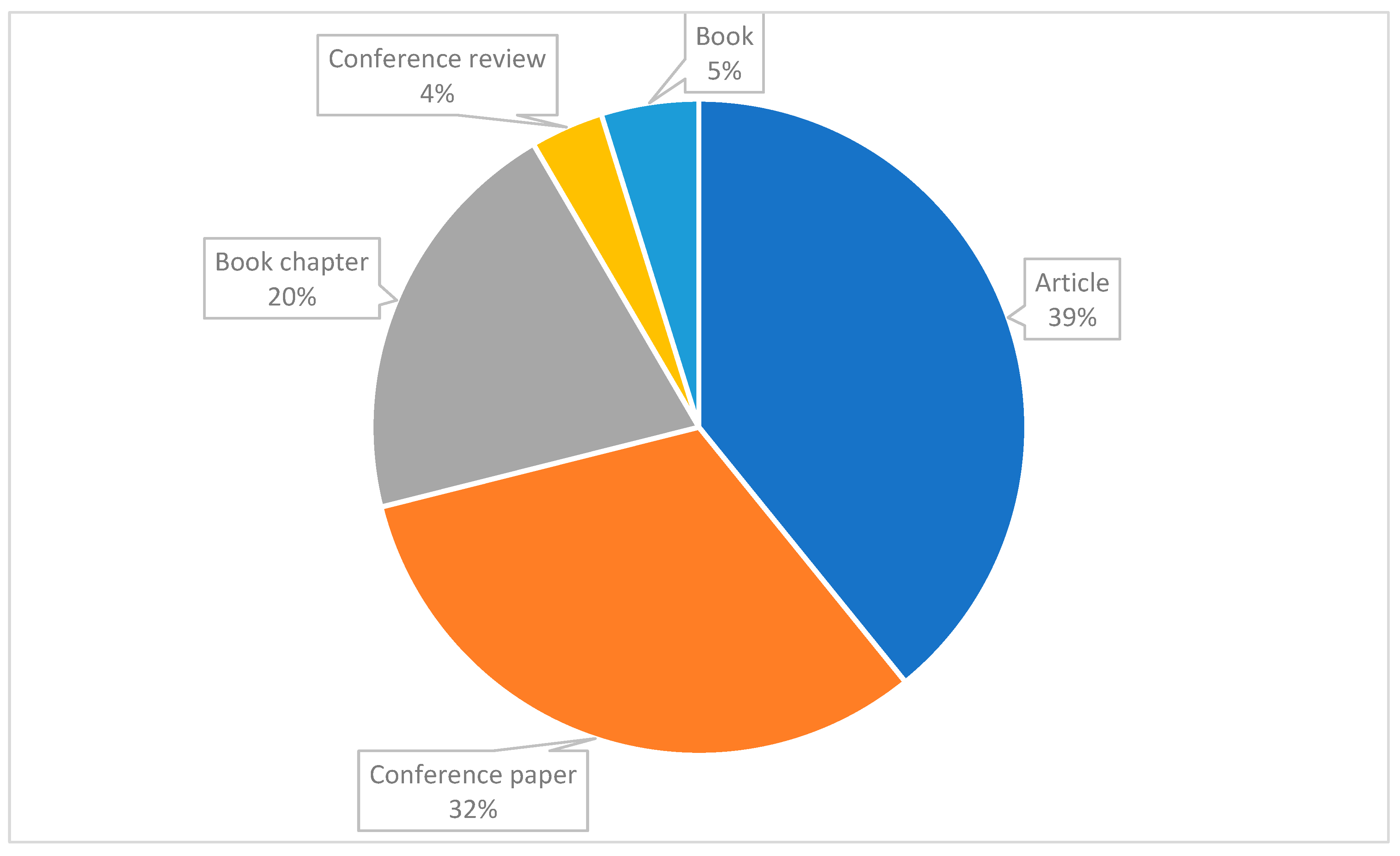

3.1.4. Publication by Type

3.1.5. Most Productive Publications

3.1.6. Most Productive Authors

3.1.7. Most Influential Articles

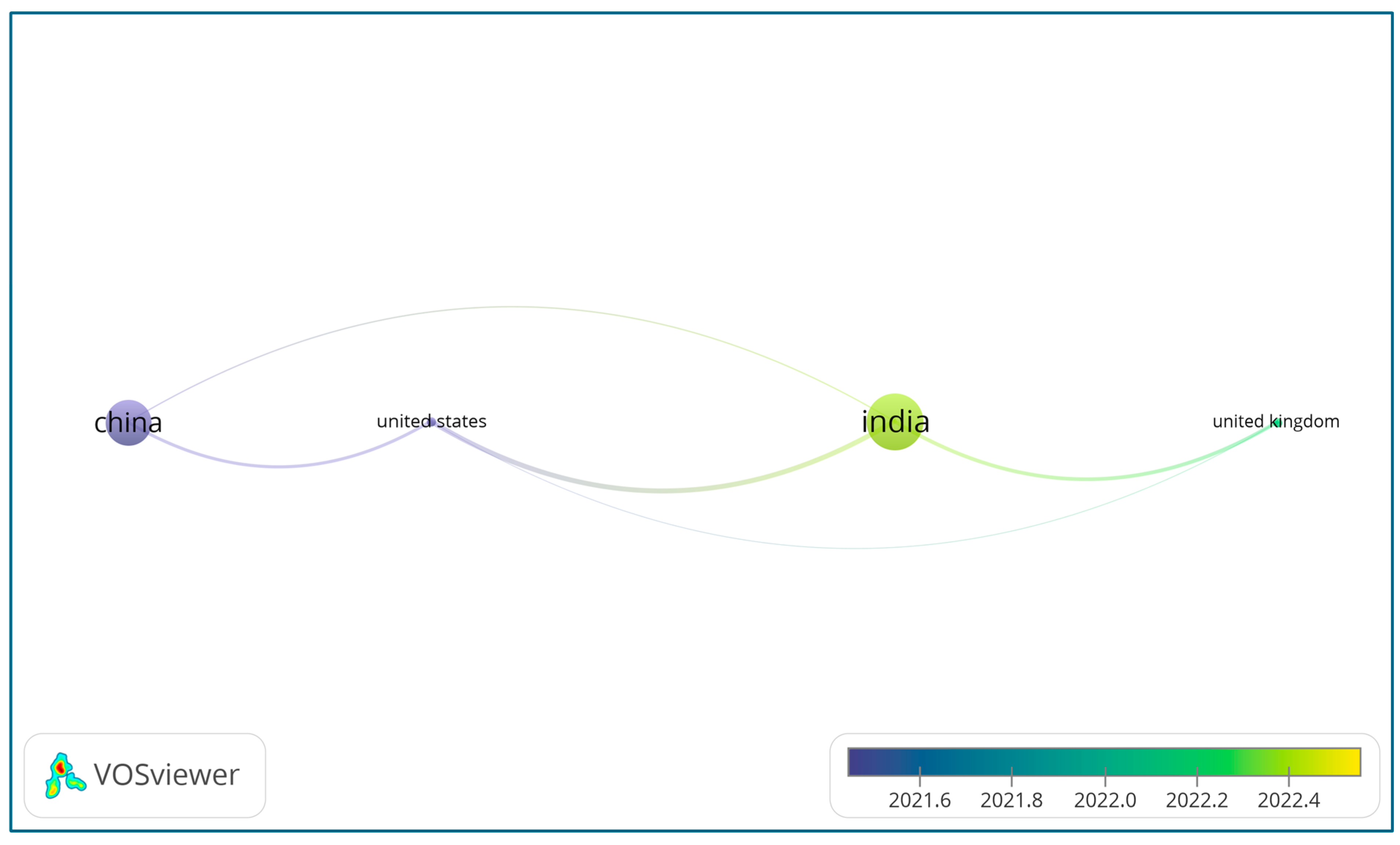

3.1.8. Overlay Visualization of Author’s Country Collaboration

3.1.9. Theoretical Application to the Bibliometric Findings—Performance Analysis

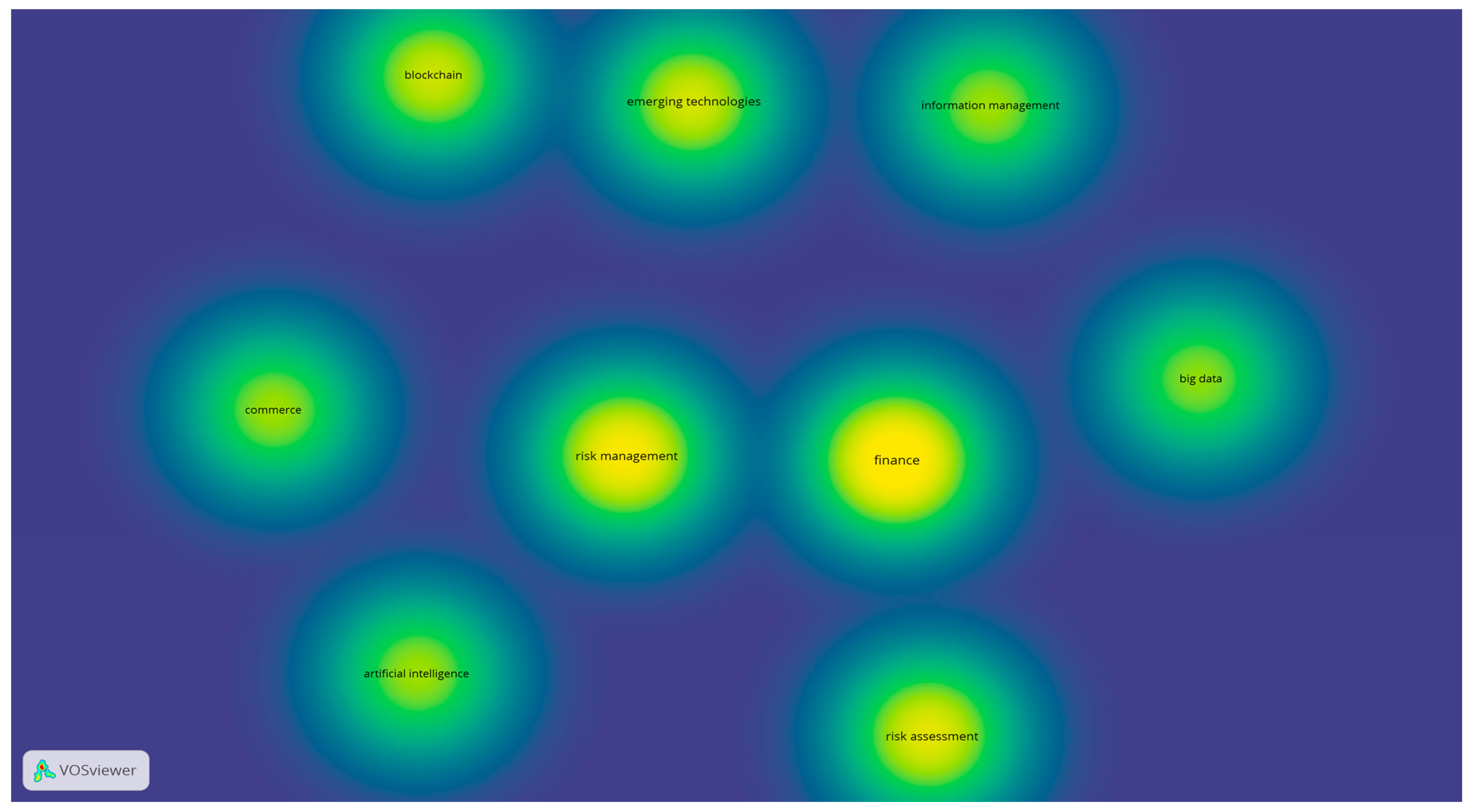

3.2. Science Mapping

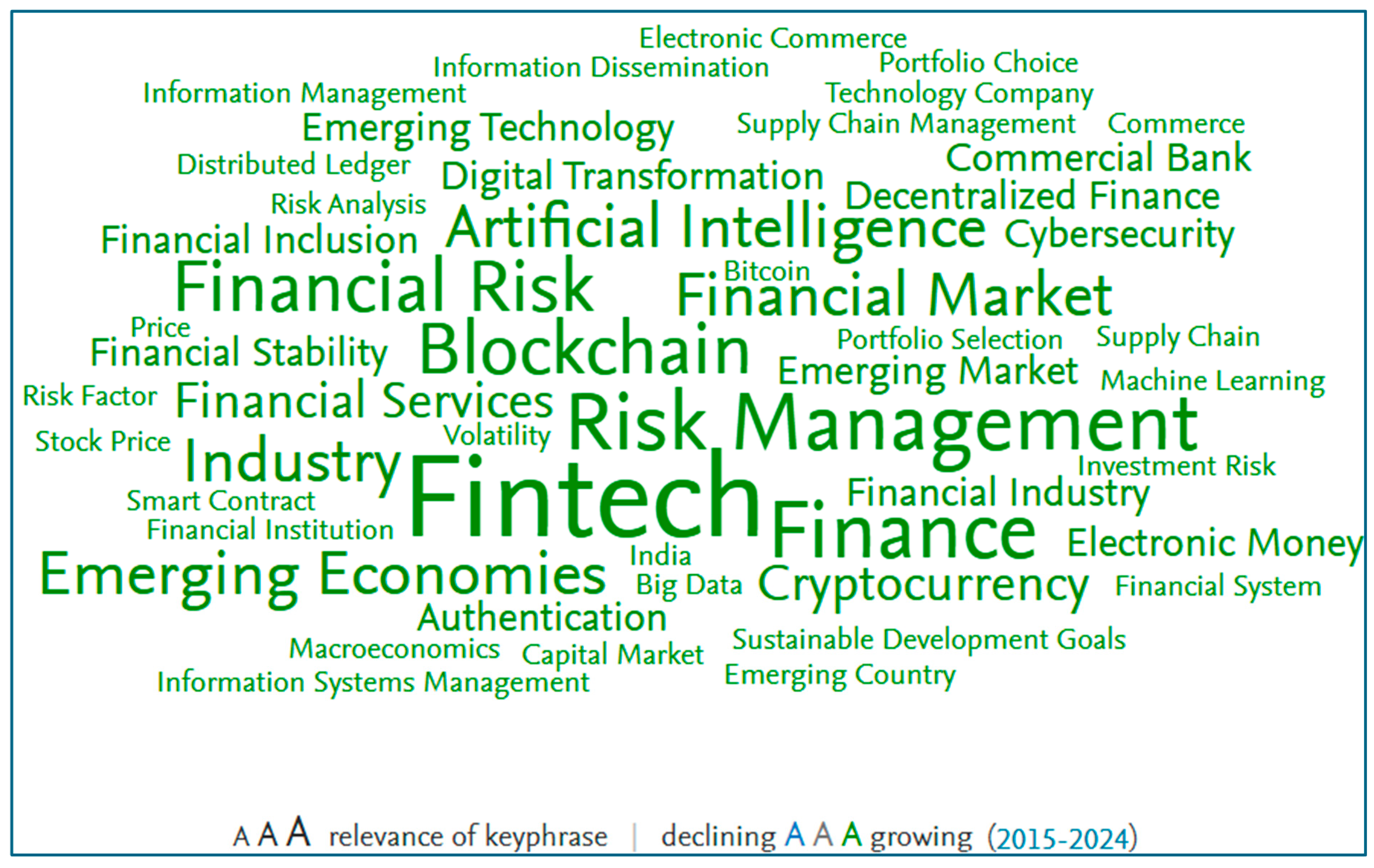

3.2.1. Key Word Analysis

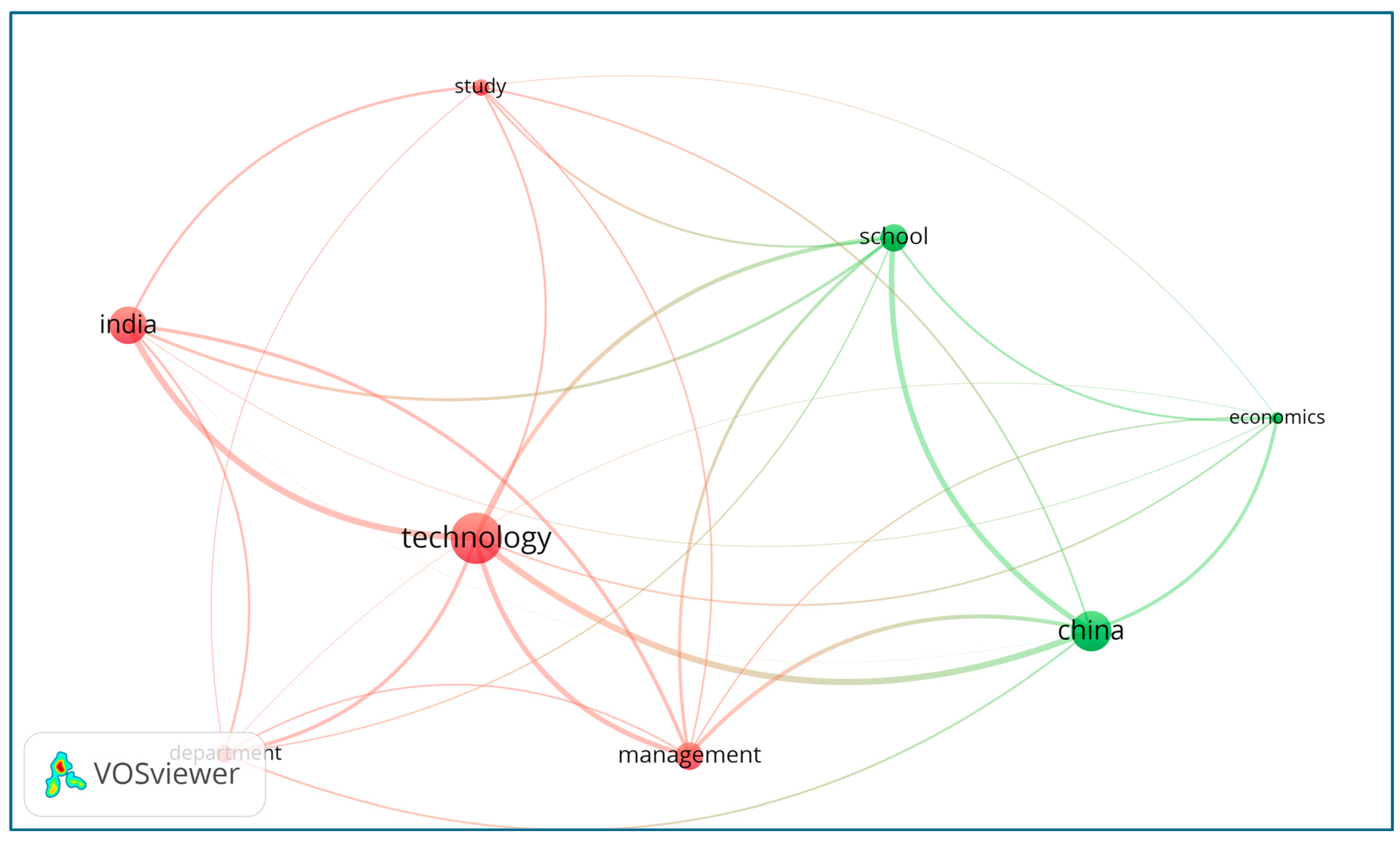

3.2.2. Visualizing Key Clusters and Themes of Emerging Risks in Fintech—China and India

Cluster 1: Fintech in India (Red Cluster)

Cluster 2: Fintech in China (Green Cluster)

4. Methodology

4.1. Assembling

4.2. Arranging

4.3. Assessing

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abraham, Katharine, John Haltiwanger, Kristin Sandusky, and James Spletzer. 2017. Measuring the gig economy: Current knowledge and open issues. In Measuring and Accounting for Innovation in the 21st Century. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Available online: https://www.nber.org/system/files/chapters/c13887/c13887.pdf (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Acosta-Prado, Julio Cesar, Joan Sebastin Rojas Rincón, Andres Mauricio Mejía Martínez, and Andres Ricardo Riveros Tarazona. 2024. Trends in the Literature About the Adoption of Digital Banking in Emerging Economies: A Bibliometric Analysis. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 17: 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agoba, Abel Mawuko, Yakubu Awudu Sare, Ebenezer Bugri Anarfo, and Christian Tsekpoe. 2023. The push for financial inclusion in Africa: Should central banks be wary of political institutional quality and literacy rates? Politics & Policy 51: 114–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajdini, Vesa. 2024. Abuse of Cryptocurrencies as a modern from of Money Laundering and Financing of Terrorism. Vizione 42: 131. [Google Scholar]

- Akartuna, Eray Arda, Shane D. Johnson, and Amy E. Thornton. 2022. The money laundering and terrorist financing risks of new and disruptive technologies: A futures-oriented scoping review. Security Journal 36: 615–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldboush, Hassan H. H., and Marah Ferdous. 2023. Building Trust in Fintech: An Analysis of Ethical and Privacy Considerations in the Intersection of Big Data, AI, and Customer Trust. International Journal of Financial Studies 11: 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljudaibi, Sara Abdulhameed, and Yusuff Jelili Amuda. 2024. Legal framework governing consumers’ protection in digital banking in Saudi Arabia. Journal of Infrastructure, Policy and Development 8: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhowaiter, Wassan Abdullah. 2020. Digital Payment and Banking Adoption Research in Gulf Countries: A Systematic Literature Review. International Journal of Information Management 53: 102102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, Franklin, Xiu Gu, and Julapa Jagtiani. 2021. A survey of fintech research and policy discussion. Review of Corporate Finance 1: 259–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Tawil, Tareq Na’el. 2023. Anti-money laundering regulation of cryptocurrency: UAE and global approaches. Journal of Money Laundering Control 26: 1150–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aras, Arzu, and Gülçin Büyüközkan. 2023. Digital transformation journey guidance: A holistic digital maturity model based on a systematic literature review. Systems 11: 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, Patrick, Balitzky Sara, and Harris Alexander. 2020. Financial stability and investor protection—BigTech—Implications for the financial sector. ESMA Report on Trends, Risks and Vulnerabilities 1: 48–59. [Google Scholar]

- Arner, Douglas W., and Jànos Barberis. 2015. FinTech in China: From the shadows? The Journal of Financial Perspectives 3: 78–91. [Google Scholar]

- Auronen, Lauri. 2003. Asymmetric information: Theory and applications. Seminar of Strategy and International Business as Helsinki University of Technology 167: 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- Aziz, Muhammad Ridhwan, Mohd Zalisham Jali, Mohd Nazri Mohd Noor, Syahnaz Sulaiman, Mohd Shukor Harun, and Muhammad Zakirol Izatmustafar. 2021. Bibliometric analysis of Literatures on Digital Banking and Financial Inclusion Between 2014–2020. Library Philosophy and Practice 5: 5322. [Google Scholar]

- Bahmanabadi, Alireza, Tayebeh Shahmirzadi, and Maziar Amirhossieni. 2023. A Comparative Study of H-Index and FWCI in Evaluation of Researchers’ Scientific Productions Case Study: Agricultural Research, Education and Extension Organization. Scientometrics Research Journal, Scientific Bi-Quarterly of Shahed University 9: 539–58. [Google Scholar]

- Bains, Parma, Arif Ismail, Fabiana Melo, and Nobuyasu Sugimoto. 2022. Regulating the Crypto Ecosystem: The Case of Stablecoins and Arrangements. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Bajwa, Ishtiaq Ahmad, Rehman Shafiq Ur, Iqbal Abid, Anwer Zaheer, Ashiq Murtaza, and Khan Muhammad Ajmal. 2022. Past, Present and Future of FinTech Research: A Bibliometric Analysis. SAGE Open 12: 21582440221131242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakare, Seun Solomon, Adenkule Oyeyemi Adeniyi, Chidiogo Uzoamaka Akpuokwe, and Nkechi Emmanuella Eneh. 2024. Data privacy laws and compliance: A comparative review of the EU GDPR and USA regulations. Computer Science & IT Research Journal 5: 528–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bank Negara Malaysia. 2022. Five Successful Applicants for the Digital Bank Licences. Available online: https://www.bnm.gov.my/-/digital-bank-5-licences (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Berghaus, Sabine. 2016. The Fuzzy Front-end of Digital Transformation: Three Perspectives on the Formulation of Organizational Change Strategies. Paper presented at the 29th Bled eConference: Digital Economy, Bled, Slovenia, June 19–22; pp. 129–44. [Google Scholar]

- Bergman, Stefan. 2012. Integral Operators in the Theory of Linear Partial Differential Equations. Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media, vol. 23. [Google Scholar]

- Bunea, Sinziana, Benjamin Kogan, and David Stolin. 2016. Banks versus FinTech: At last, it’s official. Journal of Financial Transformation 44: 122–31. [Google Scholar]

- Chadegani, Aghaei Arezoo, Had Salehi, Melor Md Yunus, Hardi Farhadi, Maryam Fooladi, Masood Farhadi, and Nader Ale Ebrahim. 2013. A Comparison between two main academic literature collections. Web of Science and Scopus Databases: Asian Social Science 9: 18–26. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Yu-Wei, Mu-Hsuan Huang, and Chiao-Wen Lin. 2015. Evolution of research subjects in library and information science based on keyword, bibliographical coupling, and co-citation analyses. Scientometrics 105: 2071–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanias, Simon, and Thomas Hess. 2016. How digital are we? Maturity models for the assessment of a company’s status in the digital transformation. Management Report/Institut für Wirtschaftsinformatik und Neue Medien 2: 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Channuie, Phongpichit. 2025. Trends in Sciences: Celebrating Record-High 2024 CiteScore. Trends in Sciences 22: 10846–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, Saloni. 2025. Mapping the Scientific Landscape of Academic Entrepreneurship in ASEAN Plus Three Countries: A Scientometric Exploration. Journal of Scientometric Research 13: s156–s169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Xiaohui. 2023. Information moderation principle on the regulatory sandbox. Economic Change and Restructuring 56: 111–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomczyk Penedo, Andres, and Pablo Trigo Kramcsák. 2023. Can the European Financial Data Space remove bias in financial AI development? Opportunities and regulatory challenges. International Journal of Law and Information Technology 31: 253–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chougule, Prashant Subhash, and Chinna Swamy Dudekula. 2024. Banking in the Future: An Exploration of Underlying Challenges. In The Adoption of Fintech. Cambridge: Productivity Press, pp. 160–91. [Google Scholar]

- Clausen, Jonathan P., Maksym Bartashevskyy, Ross Clarke, Jeffery H. Choi, Emily J. Curry, Molly M. Vora, Daniel Pare, Noorullah Maqsoodi, Robert L. Parisien, and Xinning Li. 2025. The Use of the H-index and Research Interest Score as Indices for Rank and Promotion in Academic Sports Medicine Orthopaedic Surgery in the United States. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine 13: 23259671251351331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comerio, Niccolò, and Fernanda Strozzi. 2019. Tourism and its economic impact: A literature review using bibliometric tools. Tourism Economics 25: 109–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daiya, Harsh. 2024. AI-Driven Risk Management Strategies in Financial Technology. Journal of Artificial Intelligence General science (JAIGS) 5: 194–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, Sanjiv R. 2019. The future of fintech. Financial Management 48: 981–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, Aradhita. 2025. Challenges and Opportunities in Fintech Regulation. In Examining Global Regulations During the Rise of Fintech. Edited by Mercia Selva Malar Justin, Perfecto G. Aquino, Jr. and Kumar Chandar. Hershey: IGI Global Scientific Publishing, pp. 187–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deepak, B. R. 2025. India and the Major Powers: Changing Dynamics and Future Projections. In Rising India and China: Strategic Rivalry in the Himalayas and the Indo-Pacific. Singapore: Springer, vol. 2, pp. 259–87. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Higher Education. 2022. All India Survey of Higher Education (AISHE), 2021–22 [Survey Report]; New Delhi: Ministry of Education, Government of India. Available online: https://cdnbbsr.s3waas.gov.in/s392049debbe566ca5782a3045cf300a3c/uploads/2024/02/20240719952688509.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Desai, Kavitha, and Narayani Ramachandran. 2025. Smart Money, Smarter Marketing: Fintech’s AI Evolution on Social Platforms. In Trends and Challenges of Electronic Finance. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 353–72. [Google Scholar]

- Dissanayake, Hiranya, Catalin Popescu, and Anuradha Iddagoda. 2023. A Bibliometric Analysis of Financial Technology: Unveiling the Research Landscape. FinTech 2: 527–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doe, Jhon, Jane Doe, and Max Smith. 2023. Publishing an Article with CSTEM press Journals. CSTEM Demo Journal 1: 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Donthu, Naveen, Satish Kumar, Debmalya Mukherjee, Nitesh Pandey, and Weng Marc Lim. 2021. How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: An overview and guidelines. Journal of Business Research 133: 285–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doulani, Abbas. 2020. A bibliometric analysis and science mapping of scientific publications of Alzahra University during 1986–2019. Library Hi Tech 39: 915–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Carson. 2024. Analyses of Scientific Collaboration Networks among Authors, Institutions, and Countries in FinTech Studies: A Bibliometric Review. FinTech 3: 249–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duran, Randall E., and Paul Griffin. 2021. Smart contracts: Will Fintech be the catalyst for the next global financial crisis? Journal of Financial Regulation and Compliance 29: 104–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziawgo, Tomasz. 2021. Supervisory technology as a new tool for banking sector supervision. Journal of Banking and Financial Economics 15: 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsaid, Hanaa. 2023. Interactivity in the electronic press and its impact on the readability of the paper press. The Egyptian Journal of Media Research 2023: 2037–62. [Google Scholar]

- Fischli, Roberta. 2024. Data-owning democracy: Citizen empowerment through data ownership. European Journal of Political Theory 23: 204–23. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, Ana Cristina Bicharra, Marcio Gomes Pinto Garcia, and Roberto Rigobon. 2024. Algorithmic discrimination in the credit domain: What do we know about it? AI & Society 39: 2059–98. [Google Scholar]

- Garg, Girish, Mohd Shamshad, Nikita Gauhar, Mosab Tabash, Basem Hamouri, and Linda Nalini Daniel. 2023. A Bibliometric Analysis of Fintech Trends: An Empirical Investigation. International Journal of Financial Studies 11: 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaviyau, William, and Athenia Bongani Sibindi. 2023. Anti-money laundering and customer due diligence: Empirical evidence from South Africa. Journal of Money Laundering Control 26: 224–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goddard, Michelle. 2017. The EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR): European regulation that has a global impact. International Journal of Market Research 59: 703–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gökalp, Ebru, and Veronica Martinez. 2022. Digital transformation maturity assessment: Development of the digital transformation capability maturity model. International Journal of Production Research 60: 6282–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassi, Laura, and David Lanfranchi. 2022. RegTech in public and private sectors: The nexus between data, technology and regulation. Journal of Industrial and Business Economics 49: 441–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, Christian, and Lars Hornuf. 2019. The emergence of the global fintech market: Economic and technological determinants. Small Business Economics 53: 81–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallett, Tim, and Amelia Hawbaker. 2021. The case for an inhabited institutionalism in organizational research: Interaction, coupling, and change reconsidered. Theory and Society 50: 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Haralayya, Bhadrappa. 2024. Fintech Disruption: Evaluating the Implications For Traditional Financial Institutions and Regulatory Frameworks. Educational Administration: Theory and Practice 30: 6783–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haruna, Emmanuel Umoru, William Korankye Asiedu, and Yong Jun Baek. 2025. Mapping the Research Trends on Technological Innovation in East Asia: A Bibliometric Analysis Using the Scopus Database for Future Research Direction (1982–2022). Journal of Scientometric Research 13: s3–s21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, Nathan. 2017. Estonia, the digital republic. The New Yorker 18: 12. [Google Scholar]

- Hua, Xiuping, and Yiping Huang. 2021. Understanding China’s fintech sector: Development, impacts and risks. The European Journal of Finance 27: 321–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IMF. 2025. World Economic Outlook Update Global Economy: Tenuous Resilience amid Persistent Uncertainty. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2025/07/29/world-economic-outlook-update-july-2025 (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Ismaeel, Shatha. 2024. Money Laundering: Impact on Financial Institutions and International Law-A Systematic Literature Review. Pakistan Journal of Criminology 16: 431. [Google Scholar]

- Ismayilov, Natig, and Emira Kozarević. 2023. Changing financial system architecture under the influence of the fintech market: A literature review. Journal of Contemporary Management Issues 28: 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyelolu, Toluwalase Vanessa, Edith Ebele Agu, Courage Idemudia, and Tochukwu Ignatius Ijomah. 2024. Legal innovations in FinTech: Advancing financial services through regulatory reform. Finance & Accounting Research Journal 6: 1310–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacopin, Tanguy. 2021. Fintech, Bigtech and Banks in India and Africa. In The Palgrave Handbook of FinTech and Blockchain. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 171–85. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, Anchal, Keng Suan Khor, David Beard, Toby Smith, and Caroline Hing. 2021. Do journals raise their impact factor or SCImago ranking by self-citing in editorials? A bibliometric analysis of trauma and orthopaedic journals. ANZ Journal of Surgery 91: 975–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaid, Haider Ali. 2024. Improving Fraud Detection and Risk Assessment in Financial Service using Predictive Analytics and Data Mining. Integrated Journal of Science and Technology 1. Available online: https://ijstpublication.com/index.php/ijst/article/view/13 (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Khazratkulov, Odyl. 2023. Navigating the Fin-Tech Revolution: Legal Challenges and Opportunities in the Digital Transformation of Finance. Uzbek Journal of Law and Digital Policy 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laxman, Vishnu, Nithyashree Ramesh, Senthil Kumar Jaya Prakash, and Ravi Aluvala. 2025. Emerging Threats in Digital Payment and Financial Crime: A Bibliometric Review. Journal of Digital Economy 3: 205–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Huiqing, Kai Zhao, and Jiali Li. 2024. Responding to the new research assessment reform in China: The universities’ institutional hybrid actions. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management 47: 473–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Shihan. 2023. The future of finance: Fintech and digital transformation. Highlights in Business, Economics and Management 15: 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litimi, Houda, Ahmed BenSaïda, and Mohamed Mahees Raheem. 2024. Impact of fintech growth on bank performance in GCC region. Journal of Emerging Market Finance 23: 227–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Weishu, and Haifeng Wang. 2025. Red alert: Millions of “homeless” publications in Scopus should be resettled. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology 76: 1283–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyman, Timothy, Louis de Koker, Chrissy Martin Meier, and Mehmet Kerse. 2019. Beyond KYC Utilities: Collaborative Customer Due Diligence for Financial Inclusion. Working Paper. Washington, DC: CGAP. [Google Scholar]

- Macchiavello, Eugenia, and Michele Siri. 2022. Sustainable finance and fintech: Can technology contribute to achieving environmental goals? A preliminary assessment of ‘green fintech’ and ‘sustainable digital finance’. European Company and Financial Law Review 19: 128–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahanand, Prabhat Kishor, and Abhishek Naik. 2025. One Nation One Subscription: The Future of Open Access for Indian Academia. IJSAT-International Journal on Science and Technology 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marous, Jim. 2018. The Future of Banking: Fintech or Techfin? New York: Forbes. [Google Scholar]

- Megargel, Alan, Venky Shankararaman, and Srinivas. K. Reddy. 2018. Real-time inbound marketing: A use case for digital banking. In Handbook of Blockchain, Digital Finance, and Inclusion. Cambridge: Academic Press, vol. 1, pp. 311–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdiabadi, Amir, Mariyeh Tabatabeinasab, Cristi Spulbar, Amir Karbassi Yazdi, and Ramona Birau. 2020. Are We Ready for the Challenge of Banks 4.0? Designing a Roadmap for Banking Systems in Industry 4.0. International Journal of Financial Studies 8: 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh, Hoang Pham, and Hong Pham Thi Thanh. 2022. Comprehensive Review of Digital Maturity Model and Proposal for A Continuous Digital Transformation Process with Digital Maturity Model Integration. IJCSNS 22: 741–57. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamad, Azhar. 2025. Mapping the Intellectual Landscape of Big Data in Accounting and Finance: A Decade of Bibliometric Analysis (2013–2023). Journal of Scientometric Research 14: 201–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, Halila, Aniza Ismail, Rosnah Sutan, Rahana Abd Rahman, and Kawselyah Juval. 2025. A scoping review of digital technologies in antenatal care: Recent progress and applications of digital technologies. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 25: 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monetary Authority of Singapore. 2020. MAS Announces Successful Applicants of Licences to Operate New Digital Banks in Singapore. Available online: https://www.mas.gov.sg/news/media-releases/2020/mas-announces-successful-applicants-of-licences-to-operate-new-digital-banks-in-singapore (accessed on 29 January 2025).

- Nair, Parvathy S., Atul Shiva, Nikhil Yadav, and Priyanka Tandon. 2023. Determinants of mobile apps adoption by retail investors for online trading in emerging financial markets. Benchmarking: An International Journal 30: 1623–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazzari, Mirko. 2023. From payday to payoff: Exploring the money laundering strategies of cybercriminals. Trends in Organized Crime, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nian, Hua, and Fathin Faizah Said. 2025. The Impact of ESG on Firm Risk and Financial Performance: A Systematic Literature Review. Journal of Scientometric Research 13: s144–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourahmdi, Marziyeh, and Fatemeh Rasti. 2025. Shaping Fintech through Regulations: Insights and Future Directions. Knowledge Economy Studies 2: 35–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nygaard, Arne, and Raginhild Silkoset. 2023. Sustainable development and greenwashing: How blockchain technology information can empower green consumers. Business Strategy and the Environment 32: 3801–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeng, Shadrack, Toluwalase Vanessa Iyelolu, Adetola Adewale Akinsulire, and Courage Idemudia. 2024. The transformative impact of financial technology (FinTech) on regulatory compliance in the banking sector. World Journal of Advanced Research and Reviews 23: 2008–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofoeda, Isaac, Elikiplimi K. Agbloyor, Joshua Y. Abor, and Kofi A. Osei. 2022. Anti-money laundering regulations and financial sector development. International Journal of Finance & Economics 27: 4085–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, Normah, and Zulaikha Amirah Johari. 2015. An international analysis of FATF recommendations and compliance by DNFBPS. Procedia Economics and Finance 28: 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paramesha, Mallikarjuna, Nitin Rane, and Jayesh Rane. 2024. Big data analytics, artificial intelligence, machine learning, internet of things, and blockchain for enhanced business intelligence. Partners Universal Multidisciplinary Research Journal 1: 110–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passas, Ioaniss. 2024. Bibliometric Analysis: The Main Steps. Encyclopedia 4: 1014–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, Lopakumari, and Chetan Patel. 2025. Women’s Professional Advancement in Urban Planning Industries: A Systematic Review of Barriers and Facilitators in the Indian Context. Journal of Scientometric Research 14: 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patvardhan, Neha, Mahasweta Roy, Madhura Ranade, and Vandana Vandana. 2025. Advancing Digital and Financial Engagement: A Scientometric Analysis of Web Accessibility in Fintech Payment Systems for Diverse Users. Journal of Scientometric Research 13: s170–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, Justin, Weng Marc Lim, Andy Wei Hao, Aron O’Cass, and Stefano Bresciani. 2021. Scientific procedures and rationales for systematic literature reviews (SPAR-4-SLR). International Journal of Consumer Studies 45: O1–O16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, B. Guy. 2000. Institutional Theory: Problems and Prospects. Available online: https://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/handle/document/24657 (accessed on 27 December 2024).

- Prastyanti, Rina Arum, Rezi Rezi, and Istiyawati Rahayu. 2023. Ethical Fintech is a New Way of Banking. Contingency: Scientific Journal of Management 11: 255–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pringle, Tim, and Sophia Woodman. 2022. Between a rock and a hard place: Academic freedom in globalising Chinese universities. The International Journal of Human Rights 26: 1782–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathnayake, N. D. Nishamani Bhagya. 2023. The Era of the Transition—From Traditional to Digital Banking. In Transformation for Sustainable Business and Management Practices: Exploring the Spectrum of Industry 5.0. Edited by Aarti Saini and Vikas Garg. Leeds: Emerald Publishing Limited, pp. 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RBI. 2025. Financial Inclusion Index for March 2025. Available online: https://rbi.org.in/Scripts/BS_PressReleaseDisplay.aspx?prid=60875 (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Ryu, Hyun Sun. 2018. What makes users willing or hesitant to use Fintech? the moderating effect of user type. Industrial Management & Data Systems 118: 541–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadhya, Debanjan, and Tanya Sahu. 2024. A critical survey of the security and privacy aspects of the Aadhaar framework. Computers & Security 140: 103782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, Kavita, and Rajeev Kumar. 2024. A secure decentralised finance framework. Computer Fraud & Security 2024: 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saksonova, Svetlana, and Irina Kuzmina-Merlino. 2017. Fintech as financial innovation–The possibilities and problems of implementation. European Research Studies Journal 20: 961–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampat, Brinda, Emmanuel Mogaji, and Ngyen Phong Nguyen. 2024. The dark side of FinTech in financial services: A qualitative enquiry into FinTech developers’ perspective. International Journal of Bank Marketing 42: 38–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjeev, Kumar Jha. 2025. From state to market: Shifts in access and quality in Indian higher education. International Journal of Educational Development 114: 103240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, Jonathan A. 2004. Small business and the value of community financial institutions. Journal of Financial Services Research 25: 207–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Karan, and David Kaldewey. 2025. Higher Education in India; Working Paper, 23. Bonn: Forum Internationale Wissenschaft. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11811/13105 (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Simwanza, S. Benson. 2025. Do Digital Technologies Contribute to TFP and Growth in Asia? A Theoretical and Empirical Investigation. Journal of Asian Economic Integration 7: 127–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, Mona, Hufrish Majra, Jennifer Hutchins, and Rajan Saxena. 2019. Mobile payments in India: The privacy factor. International Journal of Bank Marketing 37: 192–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreekanth, Peru, and Kedis Baye Kiran. 2024. Digital Transformation in Banks: Evidence from Indian Banking Industry. In Interdisciplinary Research in Technology and Management. Boca Raton: CRC Press, pp. 262–69. [Google Scholar]

- Stulz, René M. 2019. Fintech, bigtech, and the future of banks. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance 31: 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherdoost, Hamed. 2023. Smart Contracts in Blockchain Technology: A Critical Review. Information 14: 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanda, Alessandra, and Cristiana Maria Schena. 2019. FinTech, BigTech and Banks: Digitalisation and Its Impact on Banking Business Models. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Tenopir, Carol, Elizabeth Dalton, Allison Fish, Lisa Christian, Misty Jones, and MacKenzie Smith. 2016. What motivates authors of scholarly articles? The importance of journal attributes and potential audience on publication choice. Publications 4: 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Lin, and Nian Cai Liu. 2025. Higher education and public good: The case of China. Higher Education 89: 167–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsingou, Eleni. 2022. Effective horizon management in transnational administration: Bespoke and box-ticking consultancies in anti-money laundering. Public Administration 100: 522–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuli, Ela. 2023. Exploring digital banking adoption in developing Asian economies: Systematic literature review and bibliometric analysis. International Social Science Journal 74: 399–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungratwar, Sujeeth, Dipasha Sharma, and Satish Kumar. 2025. Mapping the digital banking landscape: A multi-dimensional exploration of fintech, digital payments, and e-wallets, with insights into current scenarios and future research. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 12: 1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velez, Sophia Beckett. 2024. Regulatory Compliance in Global Banks. In Compliance and Financial Crime Risk in Banks: A Practitioners Guide. Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited, pp. 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Shuang, Muhammad Asif, Muhammad Farrukh Shahzad, and Muhammad Ashfaq. 2024. Data privacy and cybersecurity challenges in the digital transformation of the banking sector. Computers & Security 147: 104051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windasari, Nila Armelia, Nurrani Kusumawati, Niken Larasati, and Revira Puspasuci Amelia. 2022. Digital-only banking experience: Insights from gen Y and gen Z. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge 7: 100170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Yunsong, and Shi Qi. 2025. Executive financial background and corporate digital transformation: Empirical evidence from China. Applied Economics Letters, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Yuqing. 2023. Lessons and challenges of China’s state-led and party-dominated governance model. Global Policy 14: 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Jingjing. 2024. Stabilizing leverage, financial technology innovation, and commercial bank risks: Evidence from China. Economic Modelling 131: 106599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Publication Name | Type | Cite Score | SCImago Journal Ranking (SJR) | Source Normalized Impact per Paper (SNIP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management | Journal | 9.7 | 1.134 | 2.262 |

| PLoS ONE | Journal | 5.4 | 0.803 | 1.065 |

| Journal of Intelligent and Fuzzy Systems | Journal | 4.2 | 0.364 | 0.621 |

| ACM International Conference Proceeding Series | Conference Proceeding | 2.0 | 0.191 | 0.367 |

| Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems | Book Series | 1.0 | 0.166 | 0.233 |

| Author | Total Publications | h-Index | Institution | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balusamy, Balamurugan | 2 | 31 | Shiv Nadar Institution of Eminence | India |

| Garg, Vikas | 2 | 10 | Symbiosis International | India |

| Goel, Richa | 2 | 11 | Symbiosis Centre for Management Studies, | India |

| Kiran, Ravi | 2 | 21 | Thapar Institute of Engineering & Technology | India |

| Luthra, Sunil | 2 | 76 | All India Council for Technical Education | India |

| Name of Article | Year Published | Citations-Scopus | Citations- Google Scholar | Field Weighted Citation Impact (FWCI) | Authors Countries |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A review of Blockchain Technology applications for financial services | 2022 | 263 | 342 | 8.84 | India |

| Current landscape and influence of big data on finance | 2020 | 177 | 256 | 6.65 | Poland and China |

| Contextual facilitators and barriers influencing the continued use of mobile payment services in a developing country: insights from adopters in India | 2020 | 115 | 165 | 6.84 | India, Canada, and USA |

| Proactive user-centric secure data scheme using attribute-based semantic access controls for mobile clouds in financial industry | 2018 | 92 | 122 | 5.26 | China and USA |

| Mobile payments in India: the privacy factor | 2019 | 17 | 1.53 | India and USA |

| Key Phrases | Growth % |

|---|---|

| Industry | 1800 |

| Risk Management | 1200 |

| Emerging Technology | 1100 |

| Emerging Economies | 700 |

| Emerging market | 200 |

| Gathering | Search Database: Scopus |

| Search key word: “Financial Technology” OR “FinTech” AND “Emerging Risks” | |

| Search result: 1257 | |

| Arranging | Organizing Filters: Year, Subject area, |

| Filtered Year for inclusion: 2010 to 2024 | |

| Subject Area Exclusion: Nursing, Veterinary, Dentistry, Chemistry, Physics and Astronomy, Engineering, | |

| Filtered publication stage inclusion: final | |

| Filtered by country for inclusion: India and China | |

| Filtered by language for inclusion: English | |

| Filtered search result: 167 | |

| Final search result after manual data cleaning: 162 | |

| Assessing | Analysis method: Bibliometric analysis techniques: “Performance analysis”—publication trend, most contribution authors, sponsors, journal, Science mapping—Analysis using word clouds and network analysis using key word co-occurrence |

| Reporting format: Tables, graphs, and visual maps | |

| Limitation: Scopus bibliometric data accuracy and completeness |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gaviyau, W.; Godi, J. Emerging Risks in the Fintech-Driven Digital Banking Environment: A Bibliometric Review of China and India. Risks 2025, 13, 186. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks13100186

Gaviyau W, Godi J. Emerging Risks in the Fintech-Driven Digital Banking Environment: A Bibliometric Review of China and India. Risks. 2025; 13(10):186. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks13100186

Chicago/Turabian StyleGaviyau, William, and Jethro Godi. 2025. "Emerging Risks in the Fintech-Driven Digital Banking Environment: A Bibliometric Review of China and India" Risks 13, no. 10: 186. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks13100186

APA StyleGaviyau, W., & Godi, J. (2025). Emerging Risks in the Fintech-Driven Digital Banking Environment: A Bibliometric Review of China and India. Risks, 13(10), 186. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks13100186