1. Introduction

An increasing mutual consensus has favoured separating the monetary and fiscal policy powers in pursuing the primary macroeconomic objectives of stabilising the economy and sustaining non-inflationary economic growth (

Oboh 2017). Attaining macroeconomic stability makes a country less susceptible to external shocks and helps maintain a steady course toward long-term, sustainable economic growth (

Nasrullah et al. 2023). The main tools policy authorities use to attain macroeconomic stability and long-term economic growth are monetary policy (MP) and fiscal policy (FP). Several policy instruments have been developed to assist policy authorities in achieving their objectives (

Du Plessis et al. 2007). There has been general acceptance of how both policies play a vital role in economic activities. However, different arguments exist on the preferred policy to achieve macroeconomic stability (

Šehović 2013). Before the onset of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC), the dominant view among economists and policymakers was that MP was best suited to macroeconomic volatility, while FP was primarily viewed as a secondary instrument, constrained by political lags and best reserved for long-term structural objectives (

Hammoudeh et al. 2015). FP’s focus is mainly on public finances and ensuring that long-term economic growth is achieved. The recent global economic events, such as the GFC, the increasing development of Monetary unions, and the recent COVID-19 pandemic, have seen more counteractive behaviour between these policies (

Chibi et al. 2019). Additionally, there is an inefficiency in using one policy to deter and manage economic shocks.

The increasing development of monetary unions brings about a new macroeconomic regime. With the centralised control of MP within the union, the FP need not be counteractive regarding its objectives (

Cevik et al. 2014). Maintaining stable prices is the primary responsibility of the central bank, and second in line is to support general economic objectives (

Claeys 2004). The monetary union pact rules require automatic stabilisers around fiscal positions that are structurally sound. Additionally,

Canzoneri et al. (

2003) highlight that in a monetary union, MP and FP’s effectiveness and transmission pathways can evolve in response to changing economic conditions. The success of FP will depend significantly on the interdependent interactions between the various budgetary authorities. Additionally, the 2008 GFC destabilised economies and impeded economic growth (

da Silva and Vieira 2017). This made it impossible for a single policy to stabilise and recover from the effects of the GFC. For example, many developed countries faced a “zero lower bound” after the GFC. Thus, there is a need to coordinate both policies to deal with macroeconomic shocks. The role of MP lies with the monetary authorities, while the role and responsibility of FP are entirely up to elected public authorities (

Canzoneri et al. 2003). These economic policies may entail different objectives and employ different methods to achieve macroeconomic stability (

Büyükbaşaran et al. 2020).

Policymakers and economists have investigated which economic policy is more effective. However, the effectiveness of both policies may differ according to the present economic conditions and characteristics (

Tuncer and Akıncı 2018). The effectiveness of both these policies has become more apparent with the development of the monetary unions and the recent global financial crisis. Both these events stressed the importance of coordinating these policies.

Afonso and Sousa (

2020) argue that fiscal actions may compromise the success of MP by affecting short-run demand dynamics and diminishing confidence in its effectiveness. The effects of FP on MP also include long-term alterations of the economic conditions through growth and inflation (

Afonso and Gonçalves 2020). According to

Arby and Hanif (

2010), FP focuses on attaining economic growth, and employment can sometimes be at the detriment of inflation. While the pursuit of FP to achieve macroeconomic objectives can be counteractive to MP, the same is true for the effects of MP on FP.

From a South African (SA) setting, there is a level of independence in the execution and interaction of MP and FP to ensure macroeconomic stability. The South African Reserve Bank (SARB) employs MP to regulate inflation and interest rates. At the same time, the National Treasury uses FP to regulate taxes and government expenditures (

Du Plessis et al. 2007). The two policies can sometimes complement one another, as the SARB interest rates influence the cost of borrowing for the government’s fiscal interventions (

Leshoro 2020). Moreover, they can also be counterproductive to one another in achieving set policy objectives. The SARB’s inflation-targeting instrument can often be used against the government’s planned spending priorities. The counteractive actions of both these policies have seen an increase in inflation rates to almost 9% over the years. This has been paralleled by a steady increase in the nation’s debt burden (

IMF 2023).

SA’s economic landscape, marked by structural and policy challenges, offers a critical case for studying MP-FP interactions. Persistent fiscal deficits, rising debt-to-GDP ratios, and revenue constraints have weakened countercyclical fiscal policy effectiveness (

National Treasury of South Africa 2023). While the SARB follows inflation targeting, fiscal pressures risk undermining monetary policy credibility (

SARB 2023). As a small open economy, South Africa also faces external shocks, including commodity price volatility and exchange rate instability (

Ocran 2019). These challenges highlight the need to analyse MP-FP dynamics over time.

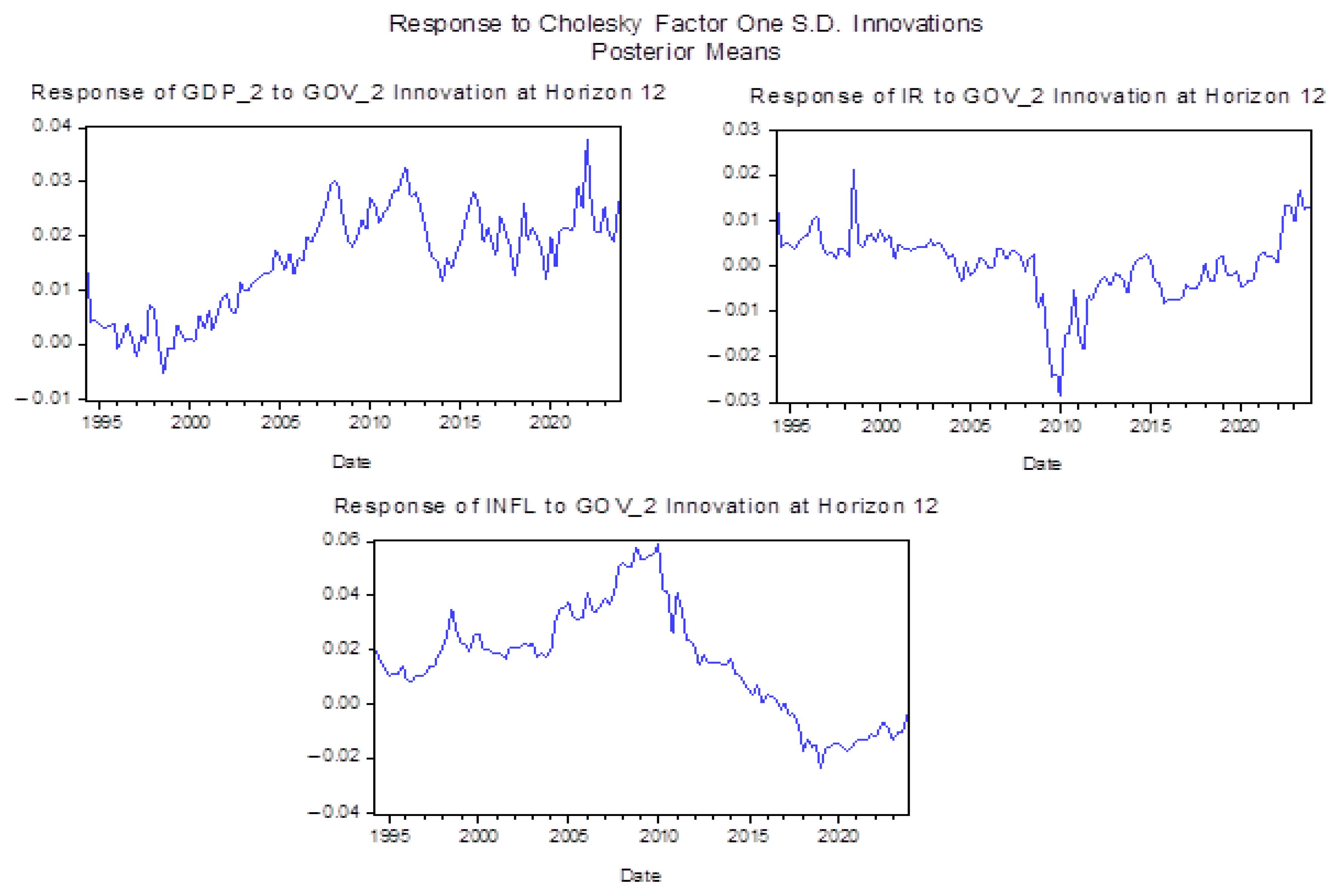

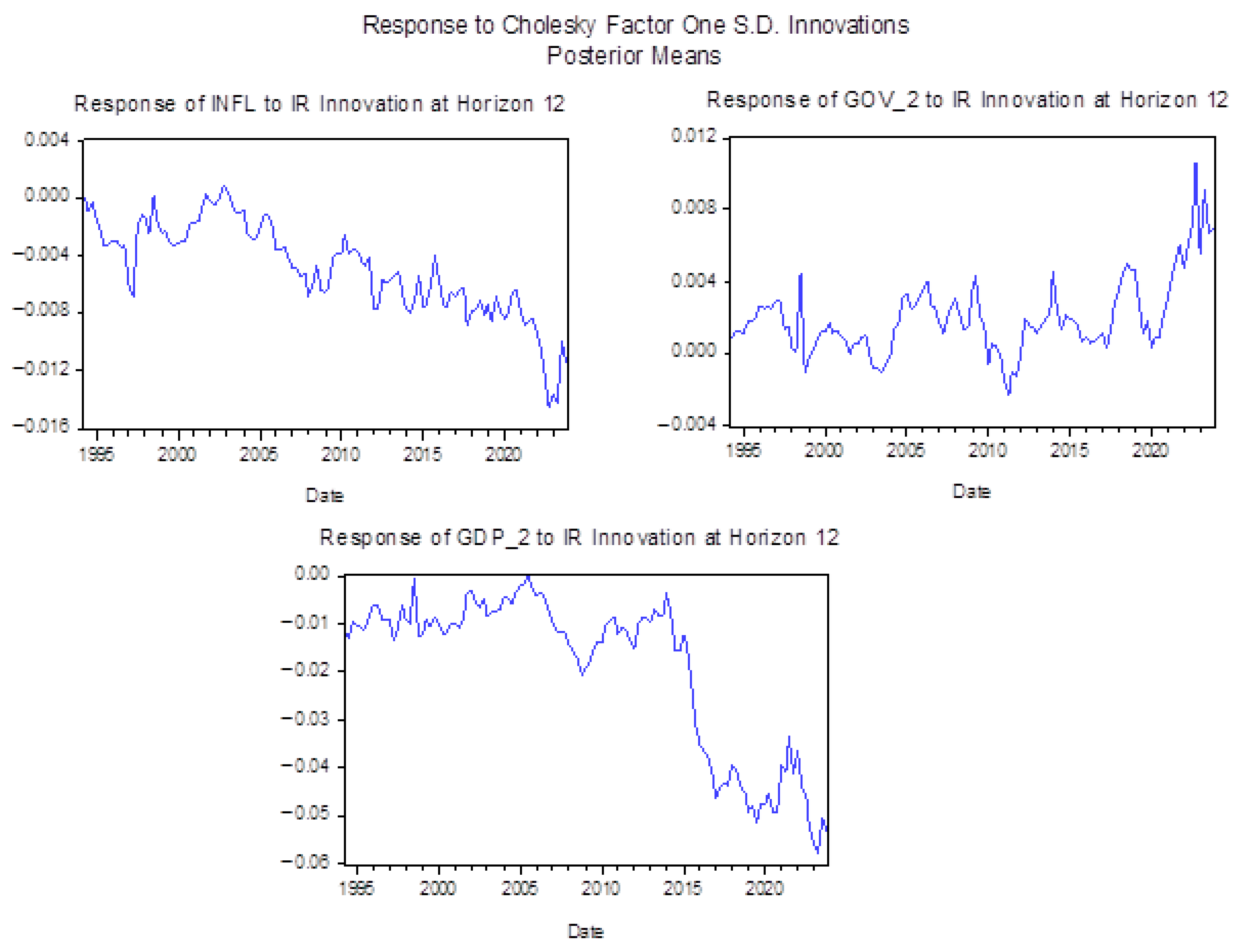

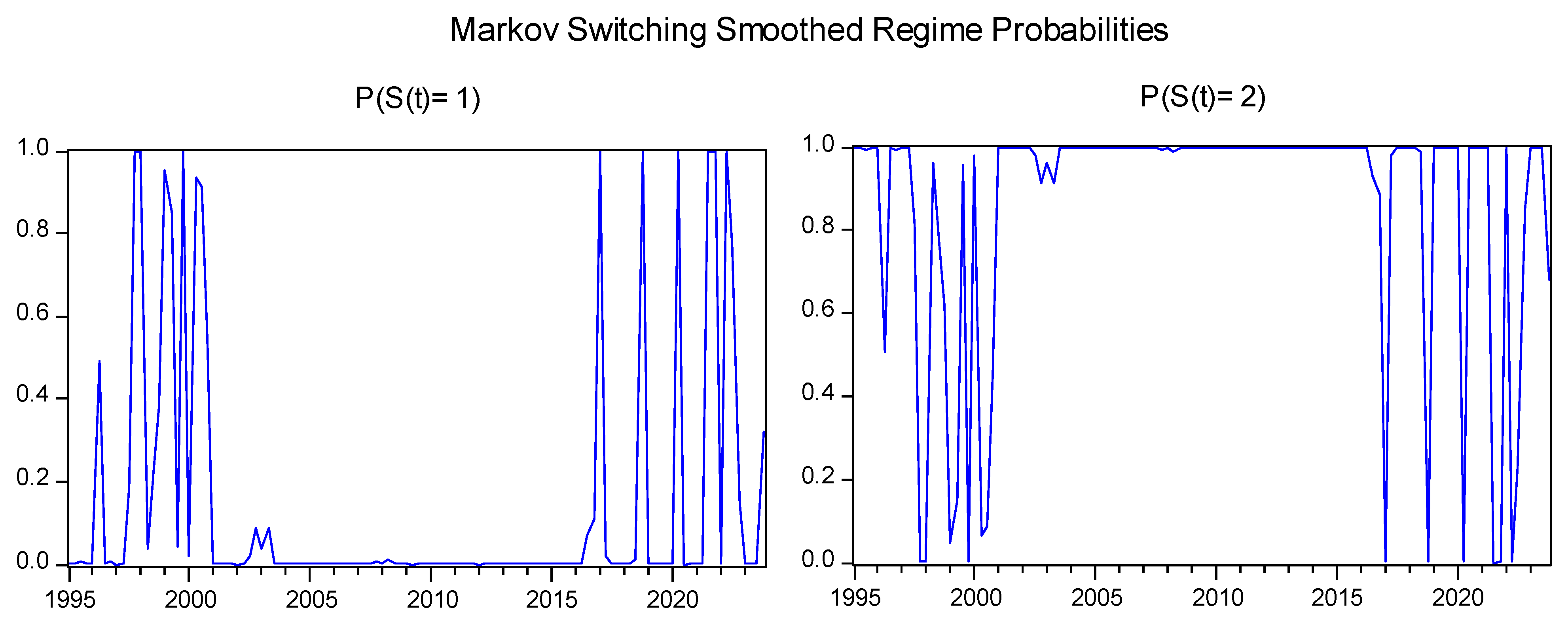

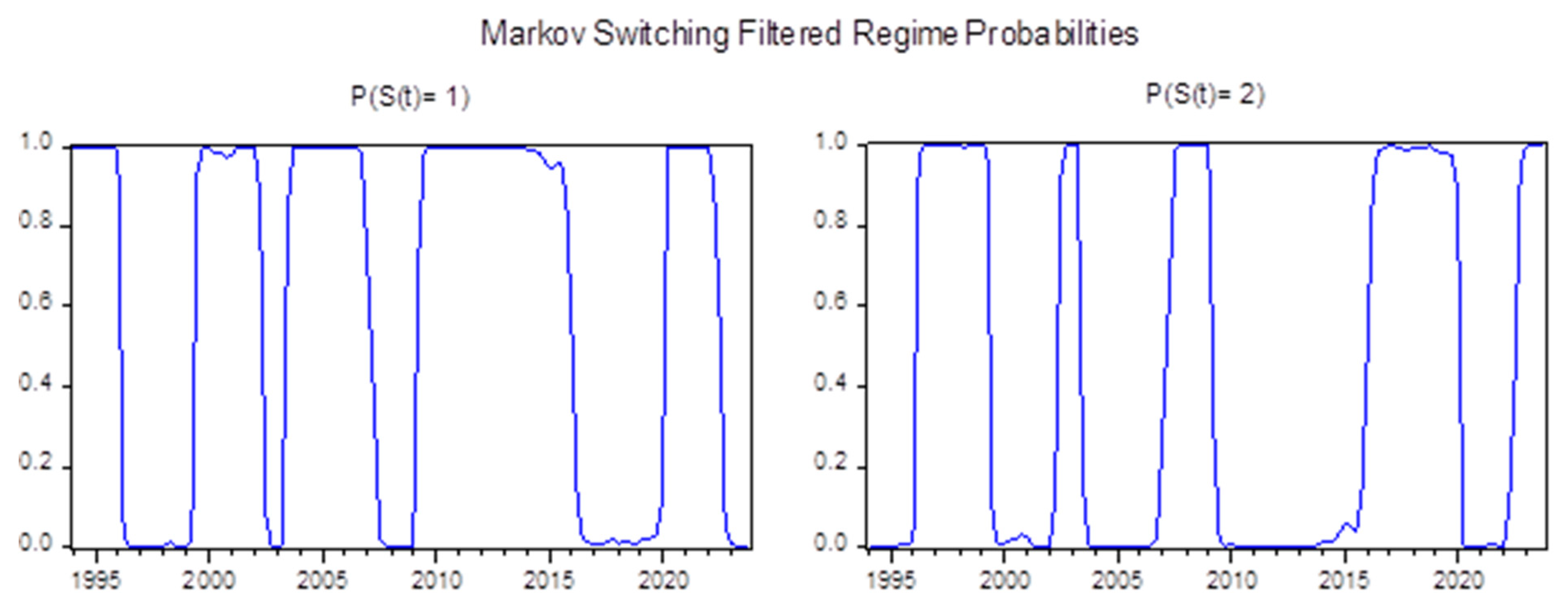

Considering those mentioned earlier, the primary objective of this study is to examine the dynamic interaction between MP and FP in SA, focusing on time-varying effects and regime shifts. To achieve this, the paper will first analyse FP’s time-varying responses to MP shocks, followed by an analysis of time-varying responses of MP to FP shocks and, lastly, exploring the interactions of MP and FP under varying economic regimes. Using a Time-Varying Parameter VAR (TVP-VAR) and a Markov Switching Dynamic Regression (MSR) framework, the analysis captures gradual and sudden shifts in policy dynamics, offering new insights into macroeconomic policy behaviour in different environments. Moreover, the paper will provide critical insights into the dynamic policy mix in SA, given its challenges with high public debt, persistent fiscal deficits and an inflation-growth trade-off economic landscape.

The organisation of the study is as follows: in

Section 2, a review of the relevant literature regarding the topic is discussed.

Section 3 discusses an analysis of the data and the methodology adopted. In

Section 4, the data and results are presented and discussed. Finally,

Section 5 concludes and makes recommendations.

2. Literature Review

Understanding the interactions of MP and FP has become increasingly crucial over the years, especially with regard to macroeconomic stability (

Blanchard 2019). The importance of understanding these interactions has deepened given the presence of persistent fiscal pressures and increasing exposure to external shocks. The interaction of these policies influences key macroeconomic indicators such as interest rates, inflation, debt levels and ultimately economic growth. Existing literature offers three dominant perspectives on MP and FP interactions: The Fiscal Theory of Price Level (FTPL), strategic policy framed by game theory, and time-varying regime switching approaches.

The Fiscal Theory of the Price Level (FTPL), first introduced by

Leeper (

1991) and further developed by

Sims (

1994),

Woodford (

1995), and

Cochrane (

2001,

2021), challenges the traditional monetarist view that central banks alone determine the price level. The FTPL posits that fiscal factors such as budget constraints, public debt levels, and debt management are pivotal in price-level determination. Under this framework, fiscal policy (FP) and monetary policy (MP) are inherently interlinked: changes in interest rates not only influence aggregate demand and output but may also exacerbate debt sustainability concerns and heighten inflationary pressures in highly indebted economies. Moreover, inflation is shaped by conventional demand-pull mechanisms and by the FTPL’s distinct debt-revaluation channels (

Cochrane 2021). Empirical evidence supports this perspective.

Maitra and Hossain (

2025), using a VAR model for India from 1985 to 2019, find that fiscal deficits tend to elevate the price level, whereas government spending can help stabilise its trajectory. Similarly,

Barro and Bianchi (

2023) apply the FTPL framework to OECD countries and show that weak fiscal discipline significantly contributes to higher inflation rates, reinforcing the theory’s relevance. In South Africa,

Sangweni and Ngalawa (

2023) employ a New Keynesian dynamic stochastic general equilibrium (NK-DSGE) model with financial frictions to examine inflation–debt dynamics. Their results corroborate that inadequate fiscal discipline undermines the South African Reserve Bank’s ability to maintain price stability, underscoring the critical role of fiscal credibility in monetary policy effectiveness.

While the FTPL frames policy interaction challenges primarily through the lens of fiscal dominance, the game-theoretic approach emphasises the strategic nature of policy decisions. This perspective conceptualises MP and FP interactions as a strategic game between policy authorities whose objectives may diverge or conflict (

Heijmans 2023). Pioneering this framework,

Dixit and Lambertini (

2003) argue that MP–FP coordination can be effectively analysed using game theory, which examines how rational players make interdependent decisions to maximise their respective objectives, considering the likely responses of others (

Zhang 2024). Within this approach, through their impact on borrowing costs and aggregate demand, interest rate adjustments influence both price stability and economic output (

Aruoba and Drechsel 2024). Conversely, government spending decisions directly affect aggregate demand and GDP growth (

Auerbach et al. 2021). Strategic misalignment in the dynamic interaction of MP-FP can result in increased inflationary pressures when a fiscal expansion coincides with accommodative MP and output contraction in the case of a simultaneous MP-FP tightening (

Hooley et al. 2021). Empirically,

Bassetto and Sargent (

2020) employ a game-theoretic framework to analyse strategic MP-FP interactions; their findings suggest that the risk of fiscal dominance, particularly loss of FP credibility, reduces the central bank’s ability to control inflationary pressures.

Chibi et al. (

2024) further support these findings by employing dynamic stochastic game theory to model policy interaction in emerging economies. That fiscal austerity often follows monetary tightening due to credibility concerns. Additionally,

Zhang (

2024) employs Nash equilibrium game theory to analyse MP-FP interactions and finds that coordination between policies minimises welfare loss effectively and is crucial for economic stability.

A third and increasingly influential strand of research emphasises the dynamic and evolving nature of policy interactions. The time-varying regime theory in the context of policy interactions refers to the notion that the dynamics and coordination of MP and FP can change over time through the influence of structural, political, and economic factors (

Bianchi and Melosi 2017). Studies employing structural vector autoregressive (SVAR), time-varying parameter (VAR) and dynamic stochastic general equilibrium (DSGE) models have indicated that the interaction of MP and FP influences key macroeconomic variables such as interest rates, government spending decisions, price stability and ultimately economic growth (

Ascari et al. 2020). For instance,

Jordà et al. (

2023) investigate policy interaction; they analyse data from 17 OECD countries from 1860 to 2020. Findings indicate that a fiscal expansion increased interest rates, especially for countries with higher debt levels. While

Corsetti et al. (

2019), in an investigation of fiscal expansion on price stability for the Eurozone, find that a fiscal expansion led to increased inflationary pressures when MP is accommodative. Where monetary expansion effects are concerned,

Reis (

2023) analyses the effect of monetary expansion on debt sustainability and finds that quantitative easing (QE) eases debt servicing costs and enables higher debt-to-GDP ratios without causing fiscal stress. On the contrary,

Shvets (

2023) argue that prolonged monetary expansions can increase fiscal dominance risk. Additionally,

Auerbach et al. (

2021) employ a TVP-VAR to analyse the effects of MP on fiscal multipliers. Findings suggest that when MP is accommodative, fiscal multipliers increase.

In SA, empirical studies examining policy interactions remain limited.

Buthelezi (

2023) employs a Markov-Switching Dynamic Regression (MSDR) model to investigate MP and FP dynamics, finding that MP generally supports FP indicators.

Majenge et al. (

2024) adopt an Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) cointegration framework and Granger causality tests on data from 1980 to 2022, showing a long-term relationship between government spending, debt, and revenue. While these studies offer important insights, their methods assume discrete regime changes or constant long-run relationships. Such assumptions may be restrictive given SA’s substantial structural and institutional shifts since the 1980s. Approaches incorporating time-varying parameters would better capture policy interactions’ gradual and evolving nature, offering a more refined understanding of how these relationships adapt across macroeconomic environments.

3. Materials and Methods

To achieve the objectives of analysing dynamic MP and FP interactions in SA, this study employs the TVP-VAR and MSDR frameworks. These advanced econometric techniques are particularly suited for South Africa due to the economy’s structural shifts, policy regime changes, and exposure to external shocks. The advantages of the TVP-VAR lie in its ability to capture time-varying policy effects where a traditional VAR assumes constant parameters, which may be limiting to SA’s economic landscape, characterised by evolving policy transmission mechanisms.

Additionally, the TVP-VAR allows for a better analysis of how policy interactions evolve. At the same time, the use of the MSDR will assist in identifying distinct economic regimes (e.g., high-inflation vs. recessionary periods) in South Africa, where MP and FP interactions may shift abruptly due to policy changes. This paper will provide a comprehensive insight into MP and FP interactions in SA by employing these two methods.

3.1. Data and Variables

The study uses secondary data to achieve the set objectives. The data is extracted from the SARB database. This study utilises quarterly time-series data spanning 1994Q1 to 2023Q4, capturing SA’s complete post-apartheid economic history. The analysis incorporates five key macroeconomic variables: consumer price index (CPI) for inflation, real GDP for economic activity, government debt-to-GDP ratio (DEBT) for fiscal sustainability, the central bank policy rate (IR) as the MP indicator and government expenditure-to-GDP (GOV_2) as the FP indicator.

3.2. TVP-VAR Model

Researchers have extensively relied on conventional VAR models to analyse how MP and FP influence macroeconomic variables over time (see

Mishra et al. 2012). The basic VAR model was initially developed by

Sims (

1980) and has been developed into different extended forms.

Primiceri (

2005) and

Nakajima (

2011) have extended and improved the model framework by incorporating time-varying parameters. Before a TVP-VAR model is made, the VAR must be specified in its basic form.

In the above Equation (1)

represents a

vector, which consists of observed variables;

represents the time

;

presents lag times; and

represents

coefficient matrices. The disturbance

denotes a

structural shock in the economy, which follows

, where

where

denotes the standard deviation. With the assumption that structural shocks follow a recursive identification pattern,

takes a lower triangular matrix form as;

The structural VAR from Equation (3) is transformed to a reduced form VAR model as follows:

The elements in the rows of

are stacked to form vector

, defining

, where the Kronecker product is denoted as ⊗. Thus, the model is further formulated as follows;

Following the works of

Primiceri (

2005) and

Nakajima (

2011), the parameters

in Equation (6) are allowed to be time-varying, and the TVP-VAR model with stochastic volatility can be written as follows:

Following

Nakajima (

2011), the lower-triangular elements in

are converted to the forms

and

for

to reduce the parameters that need to be estimated, and the parameters in Equation (7) assume a random walk process as follows:

The initial states for the time-varying parameters are assumed to be given by

,

,

. In the above matrix, there is no correlation among the time-varying parameters. Hence, the covariance matrices

,

and

are assumed to be diagonal (

Nakajima 2011).

The TVP-VAR model estimation involves the computation and estimation of several parameters. The model estimation is also tricky due to the stochastic volatility and an intractable likelihood function. To avoid this challenge, the TVP-VAR is estimated based on Bayesian inference and the Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) approaches.

Primiceri (

2005),

Nakajima (

2011), and

Banerjee and Malik (

2012) argue that the Bayesian inference framework allows the original estimation challenge to be split up into smaller estimations to deal with the issue of high-dimensional parameters more efficiently. With the MCMC approach, the joint posterior distributions of the parameters are assessed in advance under specific priors. Additionally, the MCMC approach deals with recursive sampling from lower-dimensional objects and assists with parameter explosions (

Nakajima 2011).

The priors used are derived from the work of

Nakajima (

2011), being

and

.

represents the inverted Wishart distribution,

and

denote the

diagonal elements of the matrices.

3.3. The MSDR Model

The MSDR model was initially developed by

Quandt (

1972) and

Goldfeld and Quandt (

1973). This model is applied to time series that are thought to shift between a limited number of hidden regimes, enabling the behaviour of the process to vary across different states. The transitions occur according to a Markov process. The time of transition from one state to another and the duration between state changes is random. Considering a series with an evolution of

, where

is characterised by two states, as is specified below:

where

and

represent the intercept terms in state 1 and state 2, respectively. Here,

represents the white noise error term with a variance

The two states model shifts in its intercept term (

Hamilton 1989;

Hamilton 1990). If the timing of the switches is known, the model above can be expressed as;

where

is

if the process is in state

and

if it is not. MSDR models are designed to capture swift transitions between regimes, making them well-suited for modelling data at monthly or higher frequencies. When the process is in state

s at time

t, the MSDR model to achieve the set objective of understanding MP and FP is specified as follows;

where in Equation (13)

is the dependent variable,

is the state-dependent intercept,

is a vector of exogenous variables with state-invariant coefficients,

is a vector of exogenous variables with state-dependent coefficients

, and

is an independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) normal error with mean 0, and state-dependent variance

.

xt and

may contain lags of

.

Equations (14) and (15) are the FP and MP rules, respectively. Equation (14) defines the FP equation developed by

Bohn (

1998). Where

is the FP variable, where for this study is government expenditure.

,

,

and

represent GDP, lagged debt-to-GDP ratio, and the interest and inflation rates, respectively. Equation (15) defines the MP equation as

Davig et al. (

2006) specified. Where

represents the interest rate.

,

and

represent the inflation rate, gross domestic product, fiscal variable, and government expenditure.

In the MSDR framework, the unobserved regimes evolve using a first-order Markov process. The transition probability matrix

governs the likelihood of shifting from one regime to another, where each element.

represents the probability of switching from regime

at time

to regime

at time

. The transition probabilities matrix can be specified as follows:

These probabilities are estimated jointly with the model parameters using maximum likelihood. The diagonal elements and represent the persistence of each regime, while the off-diagonal elements and capture the likelihood of switching between regimes. A high diagonal probability implies a stable regime, whereas lower values suggest more frequent transitions.

The estimated transition matrix provides insight into the duration and stability of MP and FP regimes, enabling the identification of periods characterised by different policy behaviours (e.g., active vs. passive stances)

3.4. Unit Root Testing and Lags Determination

The variables are tested for stationarity using the Augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) test. The ADF test examines the null hypothesis that a given series contains a unit root (i.e., is non-stationary). The test will be conducted on all variables at different levels and first differences, where appropriate. Additionally, to determine the optimal lag length of the model, the Akaike information criterion (AIC), the Schwarz criterion (SC) and the Hannan-Quinn criterion (HQ) are employed. These tests are applied to the constant parameter VAR.

3.5. Limitations

While the analysis offers valuable insights, it is not without limitations. The TVP-VAR is highly sensitive to lag selection, prior assumptions, and the relatively small sample size, while the MSDR framework may oversimplify gradual or overlapping regime shifts. Moreover, specifying government expenditure as a share of GDP can mechanically distort fiscal shocks, and unclear identification strategies risk confounding genuine policy effects with endogenous responses. These limitations suggest the findings should be interpreted cautiously and validated using complementary approaches.

5. Conclusions

This study attempts to understand the characteristics of South Africa’s MP and FP interactions. Using the TVP-VAR model and the MSDR, we model these interactions and attempt to identify any potential changes in policy interactions under different regimes. The main findings from the TVP-VAR model analysis indicate that GDP persists in response to a fiscal expansion, except during the 2008 GFC and COVID-19 pandemic, suggesting crowding-out effects during economic crises. This can be attributed to SA’s high debt levels and ongoing supply shocks. Contrary to conventional theory, the findings suggest that a fiscal expansion reduces inflation. These results align with

Buthelezi (

2024), who finds a decrease in CPI following a fiscal expansion. These findings reflect anchored inflation expectations, especially with the adoption of the inflation-targeting framework in SA. Conversely, the effects of a monetary expansion on GDP can be attributed to structural supply constraints and capital flight due to a loss of business confidence.

Furthermore, inflation exhibits a weak response to IR shocks, suggesting MP ineffectiveness during liquidity traps. The main findings from the MSDR analysis indicate that SA MP is active, while FP is passive. There is also a higher tendency for the economy to be in a state where MP is active and FP is passive. However, the interest rate and government expenditure exhibit a positive relationship, challenging conventional theory and alluding to fiscal dominance risks in SA.

These results necessitate understanding the characteristics of MP and FP to make informed policy decisions in dealing with unexpected economic shocks. The fiscal expansion and CPI relationship suggests that fiscal stimulus measures may fail to stimulate demand in SA. The recommendation is for much more targeted government spending, focusing on infrastructure investment. Additionally, passive FP and active MP limit policy effectiveness during economic downturns. The recommendation would be higher levels of policy coordination during economic downturns and policy design which is more regime aware, especially within SA’s volatile economic environment. While this paper furthers the understanding of MP and FP interactions, Further research can attempt to analyse the structural factors within SA that hinder the achievement of an optimal policy mix.