Abstract

This paper investigates the impact of financial inclusion on sustainable firm growth in Northern African countries (Egypt, Morocco, and Tunisia) during the period of 2007–2020. To this end, this study employs a dynamic panel threshold regression (DPTR) model. This model is a panel-data model that can capture different behaviors of data, depending on a threshold variable. The main results showed the existence of a threshold effect. This means that when financial inclusion is low (high), sustainable firm growth is limited (significant) due to the absence (presence) of appropriate financing, information, and financial tools. However, the levels of financial inclusion in North African countries are insufficient and require improvement. Therefore, it is essential for policymakers and managers to continue to promote the quality of financial inclusion by improving access to financial services and the regulatory environment to facilitate firms’ access to financing and support their sustainability.

1. Introduction

Sustainable growth is essential for any firm, as it can not only increase revenues and profits, but also contribute to the long-term viability of firms. However, achieving sustainable growth may require significant investment, which can be financed in various ways, including debt. However, not all firms can use debt as a source of financing due to constraints related to information asymmetry, such as adverse selection and moral hazard. As a result, some firms are unable to access credit, which limits their ability to grow (; ).

In recent years, financial inclusion has been the subject of intense academic and policy debates, especially in the context of firm growth (e.g., ; ). A lack of financial inclusion can limit the growth potential of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) by limiting their access to financing, insurance, and other financial services. This, in turn, can stifle innovation and reduce economic growth (). In addition, financial inclusion can improve firms’ access to traditional financing sources, such as banks and financial markets. This is due to a reduction in information asymmetries between borrowers and lenders, as well as better financial transparency (; ). Thus, financial inclusion widens the range of financing choices available to firms and enhances their ability to obtain funds, which can stimulate their growth.

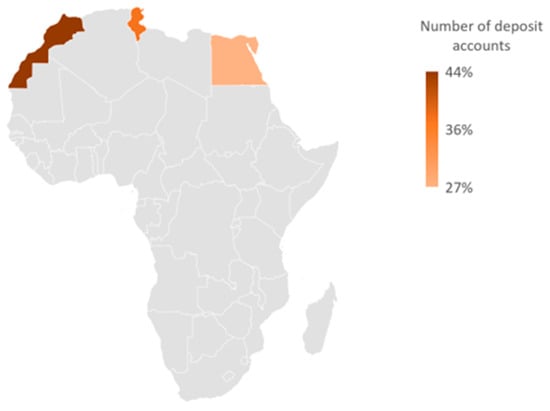

North African governments, especially those of Egypt, Tunisia, and Morocco, are focusing on strategies to encourage financial inclusion for SMEs. This is important because many SMEs struggle to access traditional bank loans, limiting their growth and job-creation potential. Although progress has been made in recent years, access to financial services remains low in the region, with only 36% of adults having a bank account (). Figure 1 illustrates a map of the number of deposit accounts with commercial banks per 1000 adults (in Tunisia, it is 37%, in Egypt, it is 27%, and in Morocco, it is 44%). However, mobile banking and other digital financial services are becoming increasingly popular, especially among young people and those in rural areas. Tunisia, Morocco, and Egypt have implemented successful financial-inclusion programs, including partnerships with microfinance institutions and national strategies to increase access to financial services for all citizens, especially SMEs and startups. The Central Bank of Egypt has launched a new financial-inclusion strategy for 2022–2025, with a focus on expanding access to financial services.

Figure 1.

Map of the number of deposit accounts in North African countries. Source: IMF FAS and authors’ calculation.

Despite the efforts made by these three countries to promote financial inclusion, it has been found that levels of financial inclusion remain relatively low. This raises concerns about the effectiveness of current policies and initiatives to support access to financial services for individuals and firms. In highlighting the low levels of financial inclusion in these countries, it is important to emphasize a critical issue that requires attention and appropriate action. In addition, by exploring the effects of financial inclusion on business growth in countries with low levels of inclusion, it is important to identify the specific barriers that limit access to financial services and hinder firms’ development. This in-depth understanding of the constraints encountered in these countries will enable the development of recommendations and targeted strategies to improve financial inclusion and stimulate sustainable firm growth.

Various theories have been set forth to explain the debt–firm-growth nexus, such as the agency theory (), the trade-off theory (), and the pecking-order theory (). These theories focus on firms’ financing choices by emphasizing the costs, benefits, and risks associated with each source of financing. However, in the era of financial inclusion, these theories are no longer sufficient to understand firms’ financing choices and their impact on sustainable growth. Indeed, financial inclusion has a significant impact on firms’ financing decisions by offering new sources of financing and improving forms’ access to existing sources. Traditional theories of capital structure do not take this new reality into account and need to be adapted to understand the effects of financial inclusion on firms’ financing choices and their growth.

From an empirical viewpoint, the results of prior studies that focused on the relationship between financial inclusion and firm growth are mixed and inconclusive. On the one hand, the few studies that examined this relationship suggested a positive impact of financial inclusion on sales growth (e.g., ; ). On the other hand, other studies indicated the existence of a nonlinear relationship between access to credit and sales growth (), and between leverage and sustainable firm growth (). Hence, this study intends to fill this research gap by examining the threshold effect of financial inclusion on sustainable firm growth in North African countries. This threshold effect indicates two types of firm: those whose level of sustainable growth decreases as they should be more financially inclusive, but only up to a certain point (threshold), where lenders begin to extend credit to them because of high levels of financial inclusion; and those who exceed the optimal level, resulting in increase in their growth.

In this context, the main objective of this paper is to analyze the impact of financial inclusion on sustainable firm growth in the North African region. Specifically, this study investigates the threshold effect of financial inclusion on sustainable firm growth. It uses a sample of Northern African countries (Egypt, Morocco, and Tunisia) from the period of 2007–2020. It also uses the dynamic panel threshold regression (DPTR) model, run on a sample of listed North African firms. Furthermore, this study investigates the non-linear relationship between financial inclusion and sustainable firm growth by considering that managers–shareholders may react positively (negatively) to high (low) levels of financial inclusion. The main findings of this paper are that financial inclusion does not necessarily lead to increased sustainable firm growth, and that a certain threshold of financial inclusion must be reached by North African non-financial firms in order to enhance their growth. Most of the current studies indicate that an increase (decrease) in financial inclusion-level always leads to sustainable (unsustainable) firm growth. However, although several studies on financial inclusion and sustainable firm growth have been conducted in other countries, there are few studies on emerging regions such as North Africa (Egypt, Morocco, and Tunisia).

This study makes an important contribution to the literature by examining the non-linear relationship between financial inclusion and sustainable firm growth in North African countries. While many studies have addressed the relationship between financial inclusion and economic growth or sustainable economic growth (e.g., ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ), few have examined sustainable firm growth specifically (). By focusing on the North African region, this study fills a research gap by providing new, region-specific knowledge. The findings may have important policy and practical implications for policy makers, financial institutions, and firms in these countries. Unlike previous research, which focused primarily on sales growth, this study uses the rate of sustainable firm growth as the dependent variable. Sustainable firm growth encompasses not only short-term financial performance, but also long-term financial performance (, ; ; ). By focusing on this more comprehensive measure of firm growth, this study seeks to assess how financial inclusion can influence long-term value creation, while considering one of the sustainable aspects of business development. This approach makes it possible to better assess the impact of financial inclusion on the overall performance and sustainability of firms. Finally, in contrast to previous studies, which focused on examining the linear relationship between financial inclusion and sustainable growth (), this study uses a DPTR model to analyze the relationship between financial inclusion and sustainable firm growth. This model differs from previous approaches, which used curvilinear or static-panel-threshold regression models (). The DPTR model is an advanced tool for identifying the threshold at which the level of change in financial inclusion has a significant impact on sustainable firm growth. By determining this threshold, this study provides valuable information on the specific conditions under which financial inclusion can have a significant effect on business performance. In addition, the econometric model used also makes it possible to identify differences in the threshold effect of financial inclusion on sustainable firm growth in different regimes (lower and higher). This provides a finer understanding of the complex relationship between financial inclusion and sustainable firm growth.

Although previous studies on the impact of financial inclusion on sustainable firm growth were conducted in other countries, there are few studies on developing countries, such as Egypt, Morocco, and Tunisia. Therefore, this research aims to answer the following research questions (RQ):

RQ1: Is there a critical threshold of financial inclusion beyond which firm sustainable growth in these countries is significantly stimulated?

RQ2: What are the specific barriers to financial inclusion faced by firms in these countries, and how can they be overcome?

The organization of this paper is as follows. Section 2 outlines the literature review and hypotheses, while Section 3 presents the methodology and data used in the study. Section 4 presents and discusses the findings, and Section 5 highlights the conclusion and implications, as well as the limitations of the study and future research directions.

2. Related Research and Hypothesis

According to (), the sustainable-growth rate is defined as the maximum speed at which a firm can increase its sales without exhausting its financial resources. This growth depends primarily on the expansion of its assets, which, in turn, is influenced by the rate of growth of its equity, provided that the firm maintains its operational efficiency and stable financial policies (, ).

For more information on this concept, () offers a complementary perspective by emphasizing that the sustainable-growth rate is the maximum annual sales-growth rate that a firm can achieve within predetermined operating, debt, and dividend ratios. These concepts are part of the financial theories on financial decisions and firm performance. More specifically, the relationship between financial inclusion and sustainable firm growth can be explained through the combination of sustainable-growth theory () and the literature related to leverage and firm performance. In fact, there is a strong relationship between the theories related to leverage and firm performance and the link between financial inclusion and sustainable firm growth. Both areas of research aim to optimize access to finance for firms. Traditional theories related to firm performance, such as the agency theory (), the trade-off theory (), and the pecking-order theory (), seek to determine the most effective mechanisms for firms to optimize their financing structure and increase their performance. Similarly, financial inclusion aims to broaden the access of firms to a variety of traditional and alternative sources of financing to stimulate their growth. Therefore, although capital-structure theories are more focused on firms’ financing choices, while financial inclusion is more focused on the availability of financing sources, both areas share the common objective of improving firms’ access to financing. Financial inclusion provides alternative sources of financing for firms due to information asymmetry (). However, SMEs face external financing challenges due to the problem of asymmetric information (). According to the (), financial constraints, such as high concentration, low competition, and the predominance of public ownership in financial institutions, are major problems for SME financing. Financial inclusiveness, which encourages financial stability and provides opportunities for sound risk management and financial facilities, can address the financial-inclusion gap among SMEs and lead to significant growth. However, the very low rate of financial inclusion suggests that there is considerable untapped potential for developing better access to finance for SMEs.

In practice, regarding the use of credit to promote firm growth, there are two important factors to consider. The first is the ability to access credit, which several studies showed to be a significant factor in enhancing firm growth (e.g., ; ; ; ; ). The second factor concerns lending relationships, which are another means through which to alleviate financing constraints. To protect themselves against the risk of default, lenders require restrictive clauses in the debt contract ().

In this context, firm managers (especially in SMEs) always seek to improve lending relationships to receive credit (; ). Thus, firms evaluate their need for external financing based on the level of their sales. However, there is an opposing viewpoint, according to which access to credit is not beneficial for small firms (; ; ; ). In fact, small firms in particular face an increased risk of a lack of adequate repayment sources. Therefore, they seek to establish close lending relationships to improve their financing conditions. In addition, on the one hand, information asymmetries (adverse selection and moral hazard) limit the ability of firms to obtain bank loans (). On the other hand, non-performing loans or economic recessions may require bankers to limit the granting of loans to firms (). This is likely to reduce firms’ sales growth, mainly resulting from credit rationing (; ; ).

However, recent studies examined the effects of financial inclusion on growth. These effects can be classified into two main levels: macroeconomic and microeconomic. At the macroeconomic level, previous studies investigated the linear and nonlinear links between financial inclusion, economic growth, and sustainable economic growth. Empirical studies on the linear correlation between financial inclusion and economic growth produced contradictory findings. Indeed, several previous studies showed that economic growth is driven by financial inclusion in both developed and developing countries (e.g., ; ; ; ; ; ; ). In addition, other studies showed the importance of financial inclusion in determining sustainable economic growth in countries (e.g., ; ; ). However, other studies revealed the opposite. In fact, these studies indicated that the inaccessibility or inadequacy of financial services is the main obstacle to the development of economies in developing countries, especially for financially limited firms or those located in remote regions, where financial services are not available (e.g., ; ). It should be noted that other recent studies explored the non-linearity between financial inclusion and economic growth, albeit using different econometric techniques (; ). These studies showed that increasing financial access for businesses and individuals leads to higher economic growth up to a certain threshold. However, beyond this threshold, this effect becomes negative in some economies. According to (), the financial system plays a crucial role in investment flows, as it facilitates the transfer of capital investments, creating value for multiple uses in the production process. Efficient financial systems use available resources to accelerate industrial productivity. Financial markets, which are integral parts of financial systems, stimulate income growth by reducing transaction costs and facilitating the distribution of resources. Consequently, financial development contributes to economic growth by encouraging capital accumulation and improving overall factor productivity.

The same finding is confirmed at the microeconomic level. More specifically, several studies have demonstrated a linear relationship between financial inclusion and firm growth, indicating that financial inclusion is a key determinant of firm growth (; ; ; ; ). In addition, () demonstrated the existence of an optimal FI threshold (particularly credit access) below which FI stimulates sales growth, but beyond which it reduces it. Referring to previous research, it is noted that studies also found a non-linear relationship between access to credit and sales growth (e.g., ; ; ; ). However, in the literature, the non-linear relationship between financial inclusion and sustainable firm growth has not been examined. This study aims to fill this gap while examining the threshold effect of financial inclusion on sustainable firm growth. Based on these different empirical studies, the hypotheses of this research are as follows:

H1.

There is a threshold effect of financial inclusion on sustainable firm growth.

H1(a).

Financial inclusion positively affects sustainable firm growth.

H1(b).

Financial inclusion negatively affects sustainable firm growth.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Data

The sample in our study included non-financial firms listed on North African stock markets, namely those of Tunisia, Egypt, and Morocco. There were several reasons for choosing these three countries. Firstly, these three countries have implemented ambitious digital transformation strategies, aiming to leverage the potential of digital technologies for industrialization, innovation, and competitiveness. They have invested in developing their digital infrastructure, skills, and ecosystems, as well as developing e-government, e-commerce, and e-learning (). Secondly, the economies of other countries in the North African region (e.g., Algeria and Mauritania) are heavily dependent on natural resources, particularly the hydrocarbon sector. This can make their economies more vulnerable to fluctuations in oil and gas prices, and potentially less diversified than those of Egypt, Tunisia, and Morocco, which have sought to diversify their economic sectors. Finally, the selection of these three countries was influenced by the availability of data on financial inclusion, especially financial data on listed non-financial firms.

We used annual data from the period of 2007–2020, excluding financial institutions. To be included in the sample, firms needed to have at least three consecutive years of available data during the study period. After applying these criteria, we obtained a final sample of 155 firms, representing 11 different industries, as classified by (), with a total of 2170 firm–year observations. Table 1 presents the distribution of the firms in each country. To minimize the influence of outliers on our analysis, we winsorized all firm-level variables at the 1st and 99th percentiles.

Table 1.

Distribution of firms.

This choice is particularly important because our study period coincided with major changes that affected the economies of the North African region, as well as the business sector. Indeed, the subprime crisis of 2007 had negative effects on the region’s economies, and the post-2010 period was marked by significant political and economic unrest, particularly with the Arab Spring, which hindered the growth of some countries in our sample, such as Egypt and Tunisia. In addition, the COVID-19 pandemic had a negative impact on the economies in the North African region, as well as on the global economy. Finally, we excluded insurance companies, financial institutions, and banks from our sample because they have different accounting methods, governance practices, and financial structures from non-financial firms.

In this study, data were collected from different sources. The Refinitiv Eikon database was used to obtain information at the firm level, while macroeconomic data, such as gross domestic product (GDP)-growth rate, were extracted from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators (WDI). Data related to the two dimensions of FI and the composite index were collected from International Monetary Fund (IMF)’s Financial Access Survey (FAS).

3.2. Econometric Model

To explore the nonlinear relationship between financial inclusion and sustainable firm growth in the North Africa region, we applied the DPTR model, developed by (), considering potential endogeneity. To test the validity of our hypothesis, we used Equation (1), where sustainable firm growth (SFG) is considered as the dependent variable, while financial inclusion is considered as the variable of interest. We included several control variables in Equation (1) due to their potential effects on SFG. Since the growth in the current year is assumed to be the result of operations in the previous year (), we established empirical model with a lag of one year for the variable of interest (FI). The empirical DPTR model’s equation was then written as follows:

where is the dependent variable, is the time-varying regressor, , , , , , and are the control variables, is an indicator function, and is the threshold variable (). The denotes the threshold parameter. The () are the error components, where is the individual fixed effects and is the idiosyncratic random disturbance. The and denote the coefficients of all exogenous variables for the lower and upper regimes, respectively. For more details, please refer to ().

3.3. Definition of Variables

3.3.1. Dependent Variable

The SFG rate represents the rate at which a firm can finance its growth using its own funds without borrowing from banks or other financial institutions. This rate is commonly used to forecast asset acquisitions, cash-flow projections, and borrowing strategies, measure long-term competitiveness and profitability, and evaluate the sustainability of long-term growth. According to (), the Higgins model () is used to calculate the SGR, which is defined as follows:

where NPR is the net-profit ratio calculated by dividing the profit after tax by net sales, ATR is the asset-turnover ratio, calculated by dividing net sales by total assets, RR is the retention ratio, calculated by dividing retained earnings by net profit, and EM is the equity multiplier, calculated by dividing total assets by total equity.

3.3.2. Independent Variable

Following (), we used two dimensions (access and usage) to measure financial inclusion. For the first dimension, we used the number of deposit accounts with commercial banks per 1000 adults, the number of ATMs per 100,000 adults (demographic penetration), and the number of ATMs per 1000 square kilometers (geographic penetration). For the second dimension, we also used two indicators, namely the outstanding deposits with commercial banks (% of GDP) and the outstanding loans from commercial banks (% of GDP). To construct the composite indicator, we followed () by using principal component analysis (PCA). Before performing the PCA, the indicators employed from each dimension must be normalized using the min-max normalization technique. Since the access dimension was composed of two indicators and the usage dimension was also composed of two indicators, we initially captured the common variation between the two indicators of each dimension using PCA and constructed the two dimensions of access and usage. We then applied PCA to extract principal component (PC) common to the two dimensions.

Two specific tests were performed in order to test the data’s applicability for factor analysis: Bartlett’s test of sphericity and the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test. The results of these two tests are reported in Table A1. The p-values of the Bartlett sphericity test were all less than 0.05 (0.00), and the KMO values were equal to 0.50, which shows that the data were applicable to the PCA. Panel B in Table 2 shows the results of the PCA. Regarding the access dimension, the eigenvalues of the three PCs were 2.745, 0.217, and 0.038, respectively. These results reveal that the first PC explained about 91% of the variance of the corresponding sample. Except for the first PC, no other PC had an eigenvalue greater than one, indicating that it was suitable to take only the first PC and extract the access dimension using the weights (i.e., 0.698, 0.704, and −0.130) assigned to the first PC. Regarding the usage dimension, the eigenvalues of the two PCs were 1.196, and 0.804, respectively. These results show that the first PC explained about 96% of the variance of the corresponding sample. Apart from the first PC, no other PC had an eigenvalue greater than one, suggesting that it was crucial to take only the first PC and extract the usage dimension using the weights (i.e., 0.7071 and 0.7071) assigned to the first PC. Finally, for FI, the eigenvalues of the two PCs were 1.822 and 0.178, respectively, which indicated that the first PC explained about 91% of the variance of the corresponding sample. Furthermore, only the first PC had an eigenvalue greater than one, so we can suppose that the first PC appropriately explained the joint variation between the two dimensions.

Table 2.

Financial-inclusion indicators across North African countries.

Following (), we then constructed a multidimensional index for FI, as follows:

where is the component weights and is the original variables. We used the same weights (i.e., 0.7071) for both dimensions. To facilitate analysis, following (), we further normalized (using min–max normalization technique) this index on a scale of 0 to 1. Note that 0 indicates financial exclusion and 1 indicates financial inclusion.

Table 2 presents the financial-inclusion indicators across North African countries. The results suggest that the levels of financial inclusion in three countries are relatively low. However, it appears that the level of financial inclusion in Morocco, particularly access to credit, is higher than that of other countries in the region.

3.3.3. Control Variables

To assess the impact of financial inclusion on sustainable firm growth, we considered several control variables that were mentioned in previous studies. We employed firm size (size) to control financial constraints, determined by the natural logarithm of total assets. To assess the firm’s ability to obtain external financing, we used the tangibility, calculated as the ratio of tangible assets to total assets (). To control the firm risk, we followed () using Altman’s Z-score (). This variable is calculated using the following formula:

where WC is working capital, TA is total assets, NI is net income, EBIT is earnings before interest and taxes, BE is book value of equity, TBVL is total book value of liabilities, and SAL is sales.

In addition, we included non-debt tax shields (NDTS), measured by the ratio of depreciation to total assets (). To evaluate the firm’s ability to meet its short-term commitments, we employed liquidity (LIQ) variable, measured as the current-assets-to-current-liabilities ratio (e.g., ; ). Finally, to control for macroeconomic stability and economic conditions, we employed GDP growth (; ). All variables are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Variable definition.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Summary Statistics and Correlation Matrix

Table 4 provides the descriptive statistics of all the variables for the period from 2007 to 2020. The average SFG was 0.30. The strong growth of financial markets and recent listings on the stock exchange partly explain this increase in the growth rates of firms in North Africa. Additionally, the financial-inclusion index had an average value of 0.301, ranging from 0.191 to 0.536. However, access to credit was still insufficient for the listed firms in the region, with an average value of 0.513, which is little higher than that of households for the use of financial services (0.543) in the USE. This situation suggests that firms in the North African region have limited access to formal financial services. Therefore, it is important that governments in the region improve financial-inclusion policies, particularly in relation to access to credit. The other variables showed steady growth from 2007 to 2020.

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics.

According to (), if the correlation coefficients between the explanatory variables are less than 0.80, multicollinearity should not have a significant impact on the multiple-regression analysis. The results reported in Table 5 indicate the absence of a strong correlation between the independent variables in our study, reinforcing the validity of the results of our multiple-regression analysis. In addition, Table 5 also reveals the findings of a variance-inflation factor (VIF) test, which was employed to check the presence of multi-collinearity among all the independent variables. The values were clearly within the acceptable limit, i.e., VIF < 5, which confirmed that multicollinearity was absent among the variables ().

Table 5.

Correlation matrix.

4.2. Baseline Results

In this subsection, we examine the threshold effect of financial inclusion on the sustainable growth of the listed firms in North Africa. To this end, we adopted the DPTR model. The findings are reported in Table 6. The results of the bootstrap linearity test prove the existence of a threshold effect of FI on the SFG at the 1% significance level. Using financial inclusion as the transition variable, the threshold value was estimated at 0.284. In addition, of the observations, 51% fell in the lower regime and 49% in the upper regime.

Table 6.

Baseline results.

The results presented in Table 6 indicate that the lagged variable coefficients of the SFG exhibited contrasting signs in different regimes (positive in the lower regime and negative in the upper regime), and that they were statistically significant at the 1% level. These results indicate that the current SFG is lower than the previous SFG, suggesting a lack of accelerated growth, and vice versa.

The findings show that the coefficients of the FI variable were significant for both regimes (lower and upper). In the lower regime, which demonstrated a low FI level, the estimated coefficient was positive and statistically significant, supporting the existence of a positive relationship between financial inclusion and SFG. However, in the upper regime, which had a high FI level, the estimated coefficient was negative and statistically significant, indicating the presence of a negative relationship between FI and SFG. Based on these results, the lower regime appears to be the optimal regime, since the coefficient is greater than the upper-regime coefficient. Specifically, a 1.0% FI leads to a 5.75% increase in SFG.

Regarding the control variables, we observed that the size variable had a negative correlation with sustainable firm growth in the lower FI regime, but a positive correlation in the upper regime. These results indicate that small firms have higher (lower) growth than large (small) firms. Although large (small) firms may benefit from considerable economies of scale, they often reach a minimum cost threshold, beyond which they cannot continue to grow. The negative correlation suggests that Gibrat’s law does not apply, and vice versa. These results are consistent with those obtained by () and ().

In addition, the tangibility (TANG) had negative and positive effects in the lower and upper regimes, respectively. From an economic viewpoint, the negative effect of the TANG on sustainable firm growth suggests that firms in North African countries do not have sufficient tangible assets to guarantee their sustainability, and vice versa. Specifically, a lack of guarantees prevents firms from accessing external financing, discourages lenders from granting loans to finance their investment projects, and ensures their sustainability.

However, firm risk (risk) had a positive correlation with sustainable firm growth in the lower FI regime, but a negative correlation in the upper FI regime. These results indicate that North African firms that are high in risk may find it more difficult to attract investors or secure financing, which can limit their ability to invest in new projects or expand their operations, and vice versa.

Furthermore, the NDTS variable had a negative and significant effect on sustainable firm growth in all the regimes. From an economic perspective, this negative correlation indicates that these North African firms with higher levels of NDTS may have lower taxable income, which may limit their ability to reinvest profits into growth opportunities. This is because they may have less cash available for investment after paying taxes.

However, the liquidity (LIQ) had a negative correlation with sustainable firm growth in the lower FI regime, but a positive correlation in the upper FI regime. Indeed, North African firms that maintain high levels of liquidity may be more conservative in their investment decisions, as they prioritize maintaining a cash cushion over pursuing growth opportunities, and vice versa. This can limit their ability to invest in new projects, expand their operations, or pursue new markets.

The macroeconomic variables had a considerable influence on sustainable firm growth. Indeed, GDP had a negative correlation with sustainable firm growth in the lower FI regime, but a positive correlation in the upper FI regime. This suggests that sustained economic growth in the region promotes firm growth, and vice versa. This is because strong economic growth stimulates demand for goods and services, resulting in increased sales and profits for listed firms.

4.3. Robustness Checks

4.3.1. Alternative Measure of Dependent Variable

To ensure the robustness of our findings, we conducted a further test by changing the SFG measure. Following () and (), we employed Van Horne’s static model of the SFG denoted by SFGA. The SFGA is measured as follows: retained profits × net profit rate × (1 + debt/equity ratio) × {1/(total assets/total sale) − 1}. The DPTR results are reported in Table 7. Our findings were consistent with those in Table 6, indicating the presence of a threshold effect of financial inclusion on sustainable firm growth. In addition, the estimated threshold value () was 0.252, which was close to the threshold value of 0.284 in the baseline results. Furthermore, the sign and significance of the coefficients of FI ( and ) were consistent with the outcomes demonstrated in Table 6. This suggests that the previous results were robust.

Table 7.

Robustness check: alternative measurement of SFG.

4.3.2. Decomposition of FI

Next, we performed an additional robustness test by examining the impact of each of the financial-inclusion components (ACC and USE) on the sustainable firm growth. To this end, we also employed the DPTR model. Table 8 presents the results, which suggest how the various components of financial inclusion affect North African sustainable firm growth. Compared with the results obtained in the previous regressions (Table 6), there were some differences, indicating the robustness of our results.

Table 8.

Robustness checks: decomposition of FI.

For the first dimension (ACC), the bootstrap test for linearity was significant at the 1% level, which confirmed the existence of a threshold effect of ACC on sustainable firm growth. The threshold value was estimated at 0.392. In the lower regime, with low ACC, the estimated coefficient () was significantly negative, suggesting that the relationship between ACC and sustainable firm growth was negative. However, in the upper regime, with high ACC, the estimated coefficient () was significantly positive, suggesting that the relationship between ACC and sustainable firm growth was positive. These results can be explained by the fact that when credit access is very high, it is more likely that some of the available credit is misallocated towards less productive uses that do not boost sustainable firm growth. This diminishes the benefits of increased access at higher levels, and vice versa.

For the second dimension (USE), the bootstrap test for linearity was significant at the 1% level, which also confirmed the existence of a threshold effect of the USE on the SFG. The threshold value was estimated at 0.293. The sign and significance of the coefficients of the USE ( and ) were consistent with the results shown in column (2). These results can also be explained by the fact that at low levels of financial-service usage (USE), firms may face capital constraints that limit their ability to grow and vice versa. As they gain more access to financing, these constraints ease, and growth accelerates.

4.3.3. Alternative Econometric Techniques

To assess the robustness of the empirical findings, this study employs three alternative econometric techniques, namely ’s () DPTR model, with a kink, ’s () DPTR model, and ’s () Static PTR model to estimate Equation (2).

According to (), the presence of a model kink depends on this condition, i.e., if for some k. The results are reported in column (1) in Table 9. The estimated threshold value () was 0.278, which was close to the threshold value of 0.284 mentioned in the baseline results. These results confirm the previous findings when the presence of a kink is considered.

Table 9.

Robustness check: changing the econometric method using DPTR model.

For ’s () model, we also considered financial inclusion as the threshold variable and the core independent variable. The findings are reported in column (2) in Table 9. We observed that the estimated threshold value () was 0.249, and the sign and significance of the coefficients of financial inclusion ( and ) were in line with the findings reported in Table 6. This suggests that the results discussed above are robust.

The results from ’s () static PTR model are reported in Table 10. The estimated threshold value () was 0.336. In addition, the coefficients of FI in the two regimes ( and ) were 0.432 and −0.187, respectively, and their sign and significance were in line with the findings reported in Table 6, suggesting that the main results were robust.

Table 10.

Robustness check: results of ’s () static PTR model.

4.4. Discussion

The objective of this study was to theoretically clarify and empirically evaluate how financial inclusion affects sustainable firm growth, addressing the mixed findings in the literature (). The literature indicates that financial inclusion is strictly related to firm sustainability, and that access to formal financial services is beneficial for sustainable firm growth (). On the other hand, previous findings also suggested that high levels of financial inclusion (access to credit) are detrimental to sales growth, as they involve costs that generate risk (). To verify whether positive and negative aspects coexist in the relationship between financial inclusion and sustainable firm growth, we examined this relationship by considering both the positive and the negative effects of financial inclusion, testing the threshold effect of financial inclusion on sustainable firm growth. To this end, we ran the DPTR model, using recent data covering the period of 2007–2020. Our results provide empirical evidence that supports hypothesis H1, that financial inclusion exerts a threshold effect on sustainable firm growth.

Furthermore, the estimated threshold indicates that there is an optimal level below which financial inclusion is beneficial for the sustainable growth of North African non-financial firms. However, above this optimal level, financial inclusion hinders the sustainable growth of these firms. This leads to lower and upper regimes (; ; ). More specifically, in the lower regime, when financial inclusion is low, a positive effect is observed on sustainable firm growth. This means that when firms have limited access to formal financial services, an increase in this access has a positive impact on their sustainable growth. This may be explained by the fact that financial inclusion improves firms’ access to the financial resources they need to invest, develop, and innovate, which stimulates their long-term growth. In this case, agency theory and Hypothesis H1(a) are accepted. North African firms are likely to have alternative sources of finance and access to credit to support their growth. Based on these results, it appears that the levels of financial inclusion in North African countries are still increasing. Therefore, it is important for governments and policy makers in this region to adopt appropriate policies to reduce the problems related to difficulties in accessing formal financial services. These results are like those found in other studies (macroeconomic (; ; ) and microeconomic (; ; ; ).

However, in the upper regime, when financial inclusion is high, there is a negative effect on sustainable firm growth. This suggests that high levels of financial inclusion may lead to additional costs and risks for firms. These costs and risks may limit the ability of firms to maintain sustainable growth, as they face greater competitive pressures and increased financial constraints. These results prove the validity of the sustainable growth and trade-off theories, supporting Hypothesis H1(b). Furthermore, this negative impact reveals that North African firms are unable to access formal financial services to grow because they are weakly inclusive. They therefore face external financing constraints. Certainly, these results are not surprising, since previous analyses showed that FI levels in North African countries are low. These results are like those found by () and (). Finally, our results provide support for the agency, trade-off, and sustainable-growth theories. Specifically, an optimal financial-inclusion threshold was detected, indicating that at low levels of financial inclusion, non-financial firms in North Africa (particularly Egypt, Morocco, and Tunisia) can count on formal financial services to maintain their sustainability. This result was in line with the predictions of agency theory. However, beyond this level, firms must modify their financing policies, limiting their access to financial services to avoid costs and risks that would jeopardize their sustainability. Under these conditions, firms can reinvest their own capital and avoid additional external financing. This is consistent with the sustainable-growth and trade-off theories. In conclusion, the validity of our findings was reinforced by the thorough robustness test.

5. Conclusions and Implications

This study attempted to examine the nonlinear relationship between financial inclusion and SFG. To this end, we used the DPTR method. The findings showed that there is a threshold effect of financial inclusion on sustainable firm growth. This means that when financial inclusion is high (low), the growth of firms is significant (limited) due to the presence (absence) of appropriate financing, information, and financial tools. However, at an optimal level, when financial inclusion decreases (increases), firms can limit (access) financing and additional resources to invest in their growth (to avoid risks), which can lead to a decrease (increase) in their growth. In this case, the agency and trade-off theories are partially accepted, as they predict the existence of a threshold effect of financial inclusion. More specifically, they are accepted for the case of the nonlinear relationship between access and sustainable growth. Previous sustainable growth, as well as financial and macroeconomic variables, are also considered significant.

5.1. Implications

These findings may be useful for managers and policy makers. Managers should focus on finding the optimal level of financial inclusion (ACC and USE) for optimizing growth. Limited access to finance constrains growth, but excessive access can also be detrimental. In addition, firms need to improve their learning and expertise in managing leverage and financial resources and closely monitor the costs of capital and interest payments. If these start to overwhelm real investment and constrain growth, excessive financial inclusion may have occurred. Policymakers should strive to expand access to finance for North African SMEs and encourage financial inclusion. However, it must be recognized that more is not always better—extreme over-indebtedness must also be avoided. Policies should be designed to ensure optimal and moderate financial-inclusion levels. In addition, macroprudential policies and countercyclical buffers that can help to curb excess leverage during economic crises should be considered. Finally, financial education and resources for North African SMEs should be improved to help them maximize the benefits of increased financial inclusion. This includes education on the prudent use of leverage, managing costs of financing, and preventing over-indebtedness.

5.2. Limitations and Future Research

This study has some limitations that open up many opportunities for future research. To ensure the applicability of the results, future studies should have a broader scope and include other African countries. In addition, future research could focus on the methods that firms can adopt to optimize the use of financial services and improve their sustainable growth. Furthermore, our sample was limited to listed firms, so we urge scholars to perform studies that also include non-listed firms in the future. Finally, this research on sustainable firm growth reflects the context of North African countries. We encourage scholars to conduct further research by examining other African countries and performing comparative analyses.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.K., A.C. and F.A.; methodology, W.K., A.C. and F.A.; software, A.C.; validation, W.K., A.C. and F.A.; formal analysis, W.K., A.C. and F.A.; investigation, W.K., A.C. and F.A.; resources, A.C.; data curation, W.K., A.C. and F.A.; writing—original draft, W.K., A.C. and F.A.; writing—review and editing, W.K., A.C. and F.A.; visualization, W.K., A.C. and F.A.; supervision, W.K., A.C. and F.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Results of Bartlett test of sphericity, KMO measure of sampling adequacy, and PCA (total variance explained).

Table A1.

Results of Bartlett test of sphericity, KMO measure of sampling adequacy, and PCA (total variance explained).

| Panel A: Tests of Applicability | |||||

| Bartlett Test of Sphericity | KMO | ||||

| Chi-Square | Degrees of Freedom | p-Value | |||

| Access dimension | 95.554 | 3 | 0.000 | 0.696 | |

| Usage dimension | 38.103 | 1 | 0.000 | 0.500 | |

| Financial inclusion | 28.663 | 1 | 0.000 | 0.500 | |

| Panel B: PCA (Total Variance Explained) | |||||

| Component | Eigenvalue | Difference | % of Variance | Cumulative Variance % | |

| Access dimension | 1 | 2.745 | 2.529 | 0.915 | 0.915 |

| 2 | 0.217 | 0.179 | 0.072 | 0.987 | |

| 3 | 0.038 | - | 0.013 | 1.000 | |

| Usage dimension | 1 | 1.196 | 0.392 | 0.958 | 0.598 |

| 2 | 0.804 | - | 0.402 | 1.000 | |

| Financial inclusion | 1 | 1.822 | 1.643 | 0.911 | 0.911 |

| 2 | 0.178 | - | 0.089 | 1.000 | |

References

- Abdul Karim, Zulkefly, Rosmah Nizam, Siong Hook Law, and M. Kabir Hassan. 2022. Does Financial Inclusiveness Affect Economic Growth? New Evidence Using a Dynamic Panel Threshold Regression. Finance Research Letters 46: 102364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adabor, Opoku, and Ankita Mishra. 2023. The Resource Curse Paradox: The Role of Financial Inclusion in Mitigating the Adverse Effect of Natural Resource Rent on Economic Growth in Ghana. Resources Policy 85: 103810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahamed, M. Mostak, and Sushanta K. Mallick. 2019. Is Financial Inclusion Good for Bank Stability? International Evidence. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 157: 403–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Ahmad Hassan, Christopher J. Green, Fei Jiang, and Victor Murinde. 2023. Mobile Money, ICT, Financial Inclusion and Growth: How Different Is Africa? Economic Modelling 121: 106220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, Muhammad, Kong Yusheng, Muhammad Haris, Qurat Ul Ain, and Hafiz Mustansar Javaid. 2022. Impact of Financial Leverage on Sustainable Growth, Market Performance, and Profitability. Economic Change and Restructuring 55: 737–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinrinola, Olalekan Oladipo, and Oladayo Folorunso. 2022. Evaluation of The Nexus Between Financial Inclusion and Economic Growth in Nigeria (1980–2020). European Journal of Accounting, Auditing and Finance Research 10: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, Edward I. 1983. Corporate Financial Distress: A Complete Guide to Predicting, Avoiding, and Dealing with Bankruptcy. Hoboken: Wiley Interscience; John Wiley and Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Attia, Eman Fathi, Hamsa hany Ezz Eldeen, and Sameh said Daher. 2023. Size-Threshold Effect in the Capital Structure–Firm Performance Nexus in the MENA Region: A Dynamic Panel Threshold Regression Model. Risks 11: 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayaydın, Hasan, and Pınar Hayaloglu. 2014. The Effect of Corruption on Firm Growth: Evidence from Firms in Turkey. Asian Economic and Financial Review 4: 607–24. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, Thorsten, Berrak Büyükkarabacak, Felix K. Rioja, and Neven T. Valev. 2012. Who Gets the Credit? And Does It Matter? Household vs. Firm Lending Across Countries. The B.E. Journal of Macroeconomics 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, Michael, Gregg A. Jarrell, and E. Han Kim. 1984. On the Existence of an Optimal Capital Structure: Theory and Evidence. The Journal of Finance 39: 857–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J. David, John S. Earle, and Dana Lup. 2005. What Makes Small Firms Grow? Finance, Human Capital, Technical Assistance, and the Business Environment in Romania. Economic Development and Cultural Change 54: 33–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, Anh Tuan, Thu Phuong Pham, Linh Chi Pham, and Thi Khanh Van Ta. 2021. Legal and Financial Constraints and Firm Growth: Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) versus Large Enterprises. Heliyon 7: e08576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, John Y. 1996. Understanding Risk and Return. Journal of Political Economy 104: 298–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, Robert E., and Bruce C. Petersen. 2002. Is the Growth of Small Firms Constrained by Internal Finance? The Review of Economics and Statistics 84: 298–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreira, Carlos, and Filipe Silva. 2010. No Deep Pockets: Some Stylized Empirical Results on Firms’ Financial Constraints. Journal of Economic Surveys 24: 731–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauvet, Lisa, and Luc Jacolin. 2017. Financial Inclusion, Bank Concentration, and Firm Performance. World Development 97: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Zhong, Sajid Ali, Majid Lateef, Ahmad Imran Khan, and Muhammad Khalid Anser. 2023. The Nexus between Asymmetric Financial Inclusion and Economic Growth: Evidence from the Top 10 Financially Inclusive Economies. Borsa Istanbul Review 23: 368–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coricelli, Fabrizio, Nigel Driffield, Sarmistha Pal, and Isabelle Roland. 2012. When Does Leverage Hurt Productivity Growth? A Firm-Level Analysis. Journal of International Money and Finance 31: 1674–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daud, Siti Nurazira Mohd, and Abd Halim Ahmad. 2023. Financial Inclusion, Economic Growth and the Role of Digital Technology. Finance Research Letters 53: 103602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirgüç-Kunt, Asli, Leora Klapper, Dorothe Singer, and Saniya Ansar. 2022. The Global Findex Database 2021: Financial Inclusion, Digital Payments, and Resilience in the Age of COVID-19. Washington, DC: World Bank Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond, Douglas W. 1984. Financial Intermediation and Delegated Monitoring. The Review of Economic Studies 51: 393–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrov, Valentin, and Sheri Tice. 2006. Corporate Diversification and Credit Constraints: Real Effects across the Business Cycle. The Review of Financial Studies 19: 1465–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donati, Cristiana. 2016. Firm Growth and Liquidity Constraints: Evidence from the Manufacturing and Service Sectors in Italy. Applied Economics 48: 1881–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Aynaoui, Karim, Larabi Jaïdi, and Akram Zaoui. 2022. Digitalise to Industrialise: Egypt, Morocco, Tunisia, and the Africa–Europe Partnership. In Africa–Europe Cooperation and Digital Transformation. London: Routledge, pp. 100–15. [Google Scholar]

- Emara, Noha, and Ayah El Said. 2021. Financial Inclusion and Economic Growth: The Role of Governance in Selected MENA Countries. International Review of Economics and Finance 75: 34–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, Saibal. 2011. Does Financial Outreach Engender Economic Growth? Evidence from Indian States. Journal of Indian Business Research 3: 74–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalan, Radhakrishnan, Gregory F. Udell, and Vijay Yerramilli. 2011. Why Do Firms Form New Banking Relationships? Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 46: 1335–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gujarati, Damodar. N. 2004. Basic Econometrics, 4th ed. New York: Tata McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, Robert C. 1977. How Much Growth Can a Firm Afford? Financial Management, 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, Robert C. 2003. Analysis for Financial Management, International Edition. Boston: Mc Graw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, Shahzad, Raazia Gul, and Sabeeh Ullah. 2023. ‘Role of Financial Inclusion and ICT for Sustainable Economic Development in Developing Countries’. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 194: 122725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, Kim P., and Robert J. Petrunia. 2010. Age Effects, Leverage and Firm Growth. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 34: 1003–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, Michael C., and William H. Meckling. 1976. Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure. Journal of Financial Economics 3: 305–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khémiri, Wafa, and Hédi Noubbigh. 2020. Size-Threshold Effect in Debt-Firm Performance Nexus in the Sub-Saharan Region: A Panel Smooth Transition Regression Approach. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance 76: 335–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khémiri, Wafa, and Hédi Noubbigh. 2021. Joint Analysis of the Non-Linear Debt-Growth Nexus and Capital Account Liberalization: New Evidence from Sub-Saharan Region. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance 80: 614–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremer, Stephanie, Alexander Bick, and Dieter Nautz. 2013. Inflation and Growth: New Evidence from a Dynamic Panel Threshold Analysis. Empirical Economics 44: 861–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Chien-Chiang, Chih-Wei Wang, and Shan-Ju Ho. 2020. Financial Inclusion, Financial Innovation, and Firms’ Sales Growth. International Review of Economics and Finance 66: 189–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Na, and Di Wu. 2023. Nexus between Natural Resource and Economic Development: How Green Innovation and Financial Inclusion Create Sustainable Growth in BRICS Region? Resources Policy 85: 103883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcelin, Isaac, Aklesso Y. G. Egbendewe, Djoulassi K. Oloufade, and Wei Sun. 2022. Financial Inclusion, Bank Ownership, and Economy Performance: Evidence from Developing Countries. Finance Research Letters 46: 102322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinari, Massimo. 2013. Joint Analysis of the Non-Linear Debt–Growth Nexus and Cash-Flow Sensitivity: New Evidence from Italy. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics 24: 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, Stewart C., and Nicholas S. Majluf. 1984. Corporate Financing and Investment Decisions When Firms Have Information That Investors Do Not Have. Journal of Financial Economics 13: 187–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nizam, Rosmah, Zulkefly Abdul Karim, Tamat Sarmidi, and Aisyah Abdul Rahman. 2021. Financial inclusion and firm growth in ASEAN-5: A new evidence using threshold regression. Finance Research Letters 41: 101861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, Blandina, and Adelino Fortunato. 2006. Firm Growth and Liquidity Constraints: A Dynamic Analysis. Small Business Economics 27: 139–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, Ilhan, and Sana Ullah. 2022. Does Digital Financial Inclusion Matter for Economic Growth and Environmental Sustainability in OBRI Economies? An Empirical Analysis. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 185: 106489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, Rudra P., Mak B. Arvin, Mahendhiran S. Nair, John H. Hall, and Sara E. Bennett. 2021. Sustainable Economic Development in India: The Dynamics between Financial Inclusion, ICT Development, and Economic Growth. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 169: 120758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahaman, Mohammad M. 2011. Access to Financing and Firm Growth. Journal of Banking and Finance 35: 709–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, Faheem Ur, and Md Monirul Islam. 2023. Financial Infrastructure—Total Factor Productivity (TFP) Nexus within the Purview of FDI Outflow, Trade Openness, Innovation, Human Capital and Institutional Quality: Evidence from BRICS Economies. Applied Economics 55: 783–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, Myung Hwan, and Yongcheol Shin. 2016. Dynamic Panels with Threshold Effect and Endogeneity. Journal of Econometrics 195: 169–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, Myung Hwan, Sueyoul Kim, and Young-Joo Kim. 2019. Estimation of Dynamic Panel Threshold Model Using Stata. The Stata Journal 19: 685–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, Dinabandhu, and Debashis Acharya. 2018. Financial Inclusion and Economic Growth Linkage: Some Cross Country Evidence. Journal of Financial Economic Policy 10: 369–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiglitz, Joseph E., and Andrew Weiss. 1981. Credit Rationing in Markets with Imperfect Information. The American Economic Review 71: 393–410. [Google Scholar]

- Van Horne. 1987. Sustainable Growth Modeling. Journal of Corporate Finance 2: 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Rui, and Hang (Robin) Luo. 2022. How Does Financial Inclusion Affect Bank Stability in Emerging Economies? Emerging Markets Review 51: 100876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank Group. 2016. Competition in the GCC SME Lending Markets: An Initial Assessment. Washington, DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Xueping, and Chau Kin Au Yeung. 2012. Firm Growth Type and Capital Structure Persistence. Journal of Banking and Finance 36: 3427–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Liu, and Youtang Zhang. 2020. Digital Financial Inclusion and Sustainable Growth of Small and Micro Enterprises—Evidence Based on China’s New Third Board Market Listed Companies. Sustainability 12: 3733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Kai Quan, and Hsing Hung Chen. 2017. Environmental Performance and Financing Decisions Impact on Sustainable Financial Development of Chinese Environmental Protection Enterprises. Sustainability 9: 2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).