Building a Macroeconomic Simulator with Multi-Layered Supplier–Customer Relationships

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Works

2.1. Macroeconomic Approach and Agent-Based Computational Economics

2.2. Sector-Focused Approach

2.3. Advantages and Disadvantages of the Two Approaches

3. Model

3.1. Overall Attributes of the Model

- Firm Agents: firms develop a production strategy, secure the necessary labor and intermediate input materials, and then manufacture products. Wages are paid to employees. Products are sold to households and firms through supplier–customer relationships. Firms also seek loans from banks to fund their operations and cover shortfalls. Meanwhile, the government taxes the profits earned from business activities. After-tax profits are distributed to households as dividends, and the remainder is kept in bank deposits.

- Banking Agents: banks accept deposits from households and firms while lending to firms, but not to households. When they have excess funds, they invest them in government bonds. Banks are subject to financial regulations, such as liquidity ratio regulations, and they must borrow short-term funds from the central bank when they do not have enough funds to meet these regulations. Banks do not employ workers.

- Household Agents: households provide labor to firms and the government in exchange for wages. Wages are accumulated in the form of bank deposits. They spend their wages and some of their accumulated assets to consume and purchase goods from firms. Households do not borrow. Households are shareholders in firms and banks, depending on the size of their assets. They receive distributions from the firms’ and banks’ profits. In addition, they earn interest on their bank deposits. Moreover, they receive unemployment benefits from the government while unemployed. They must pay income taxes to the government if they receive income from wages or dividends.

- Government Agent: the government hires and compensates government employees. It also provides unemployment benefits to people who are unemployed. Revenue is generated by the amount of taxes collected from each entity, and if the fiscal balance is negative, the government issues government bonds.

- Central Bank Agent: the central bank is responsible for issuing legal tender, maintaining central bank accounts for banks and the government, and holding central bank reserves. It also holds the portion of government bond issues that banks do not hold. The central bank lends short-term funds to banks to meet their funding needs. The government receives all interest income from government bond holdings and short-term lending. The central bank does not employ workers.

3.2. Order of Events

3.3. Construction of Business-to-Business Supplier–Customer Networks

- With the number of firm agents as , we generate a matrix (called the SC matrix), where the rows of the SC matrix represent product sales destinations, and the columns represent intermediate input material suppliers. For example, the first row represents firm 1’s product sales destinations, and the first column represents the suppliers of intermediate input materials required by firm 1 to manufacture its product.

- Determine the number of firms to which products are sold per firm according to the following probabilities:.According to Fujiwara and Aoyama (2008), the number of clients for Japanese firms follows the cumulative frequency distribution , and Fujiwara and Aoyama (2008) estimated as , where x represents the thickness of the right hem of the distribution, or the large proportion of large values in the frequency distribution.2 Such probabilities are based on Fujiwara and Aoyama (2008) and have been adjusted to account for the number of firm agents. The number of clients of the final consumer goods firms is set to zero.

- For each firm, select a destination firm randomly from the remaining firms, excluding itself, based on the number of destination firms determined in the previous step. Accordingly, 1 is entered in the cell corresponding to the number of destination firms in the row for the selling firms in the SC matrix. If a company does not have any intermediate input material suppliers, it is assigned a supplier.

- The proportion of the value of intermediate input materials required for a firm to manufacture one product is distributed equally among the suppliers of intermediate input materials. The value ratio of intermediate input materials procured by firm i from the intermediate input material supplier, firm j, is denoted by . To determine the proportions of the values, we divide the value of each cell by the sum of the columns in the SC matrix.

3.4. Demand Matching

| Algorithm 1 Market demand–supply matching process |

|

3.5. Agent Behaviors

3.6. Firm Behavior

3.6.1. Production Planning

3.6.2. Product Price

3.6.3. Firms’ Profits

3.6.4. Firms’ Finances

3.6.5. Labor, Credit, Product Trading, and Deposit Market

3.6.6. Firms’ Bankruptcy

3.7. Bank Behavior

3.7.1. Bank Loans

3.7.2. Financial Regulations

3.7.3. Deposit Interest Rates

3.7.4. Bank Profit

3.7.5. Bank Bankruptcy

3.8. Household Behavior

3.8.1. Providing Labor

3.8.2. Consumption

3.9. Government Behavior

3.10. Central Bank Behavior

4. Simulation Results

4.1. Simulation Settings

4.2. Results

5. Discussion

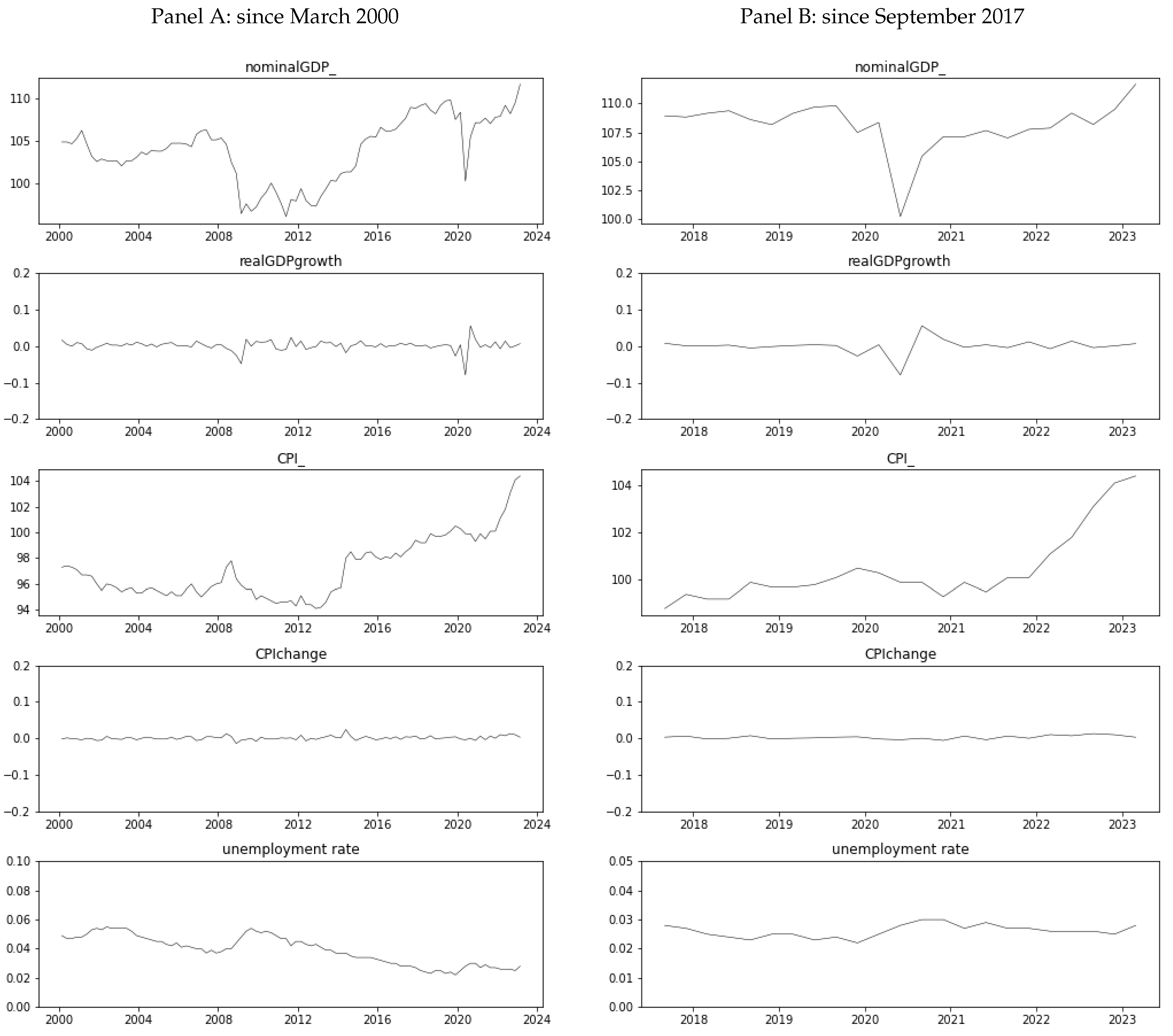

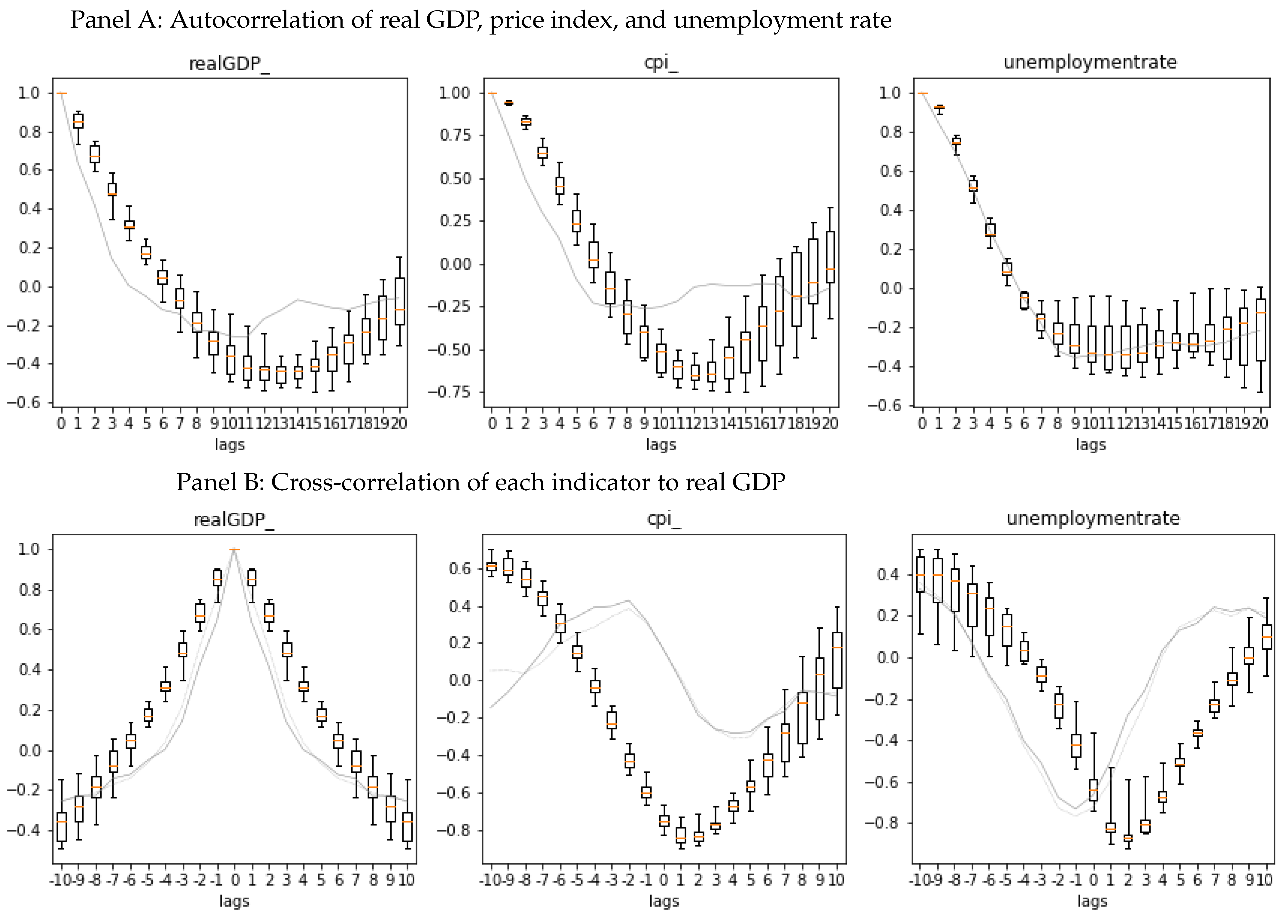

5.1. Validation

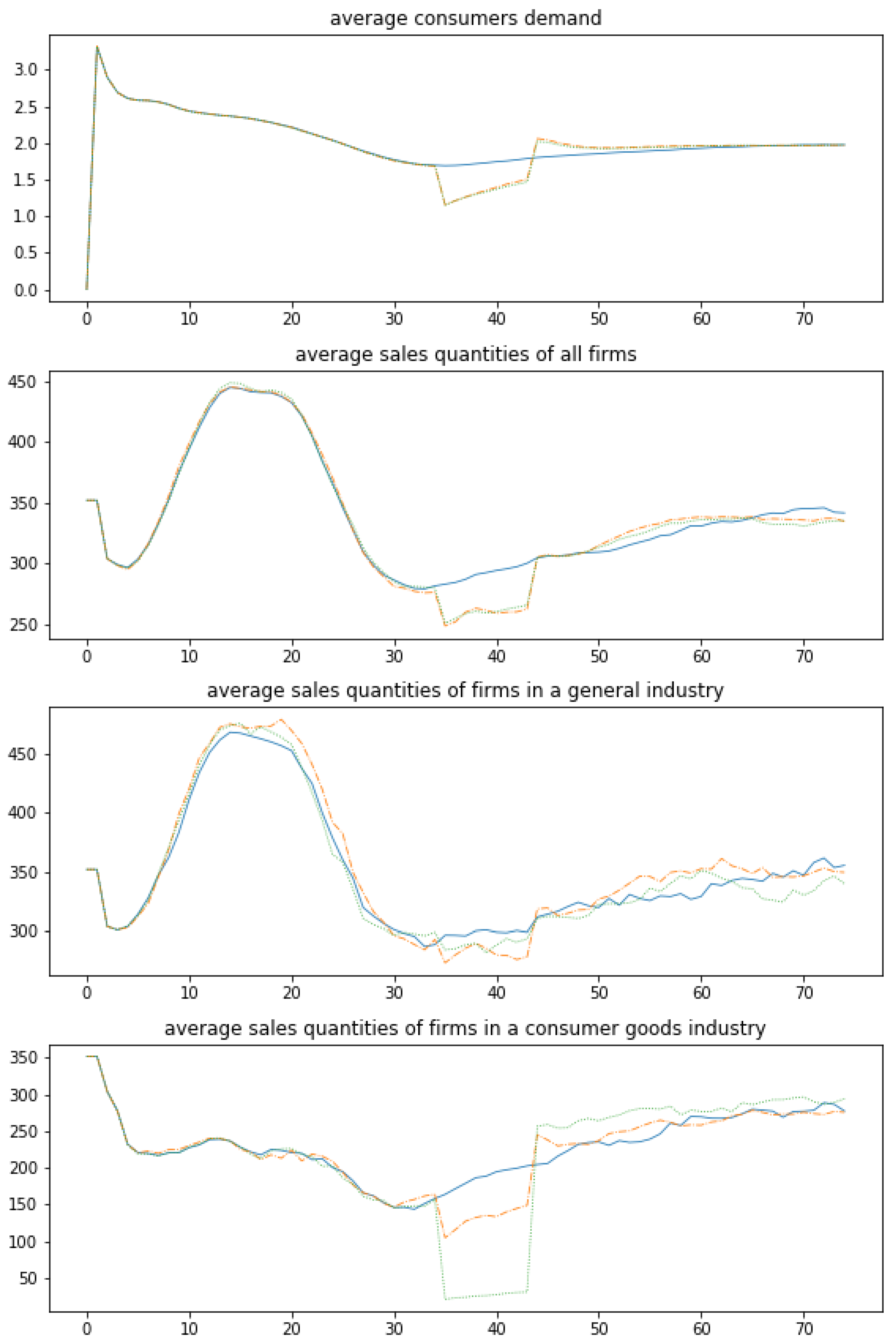

5.2. Rebound of the Economy after the Resolution of Economic Shocks

5.3. Avoidance of Final Consumer Goods during Economic Shocks

5.4. Sensitivity Analysis

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| No. | Event | Outline |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Production planning | Each firm updates its expected product sales and production volume. |

| 2 | Firm labor demand | Each firm estimates the labor required. |

| 3 | Price, interest rate, and wage setting | Each agent estimates the value of the goods that each entity can offer. (Firms, banks, and households determine product prices, deposit and lending rates, and desired wage levels, respectively.) |

| 4 | Planning for ordering intermediate inputs | Each firm estimates the intermediate input materials required. |

| 5 | Business-to-business product market (demand) | A customer firm places an order with the supplier firms for the number of intermediate inputs required. Note that the intermediate inputs ordered and received are used in production after the next step. |

| 6 | Credit market (demand) | Each firm calculates its financing needs, selects a bank to apply for a loan, and applies for a loan. |

| 7 | Credit market (supply) | Banks evaluate the loan applications received and provide loans to the successful applicants. |

| 8 | Labor market | Firms and governments interact with households to secure labor. |

| 9 | Production of products | Firms produce products based on intermediate inputs and labor inventories. |

| 10 | Business-to-business product market (supply) | Supplier firms sell products to customer firms based on order quantity and production volume. |

| 11 | Business-to-household product trading market | Households purchase products from firms and consume. |

| 12 | Interest rates, government bonds, and loan repayments | Arrangement of loan/loan relationships (firms repay part of the principal and pay interest on loans, the government repays the principal and pays interest on government bonds, and banks repay the principal and pay interest if they receive short-term funding from the central bank, along with interest payments on deposits). |

| 13 | Wages and unemployment benefits | The firms and government pay wages to households. The government pays unemployment benefits to the unemployed. |

| 14 | Tax payments | Taxes on profits and income are paid to the government. |

| 15 | Dividends | Firms and banks pay a portion of their after-tax profits as dividends to households. |

| 16 | Bankruptcy | Bankruptcy resolution for any failed firms and banks. |

| 17 | Depositor selection | Firms and households choose the bank where they deposit their cash holdings. |

| 18 | Government bond purchases | The government issues new government bonds depending on fiscal balance, and the banks purchase them. The central bank holds any remaining amount. |

| 19 | Short-term funds (liquidity) supply | The central bank provides short-term funds to banks upon the bank’s request. |

| Category | Symbol | Item | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of agents | Firms | 110 | |

| Households | 8000 | ||

| Banks | 10 | ||

| Gov. | 1 | ||

| Central bank | 1 | ||

| Product-related | Physical labor productivity | 8.0 | |

| Raw material productivity | 1.5 | ||

| Initial firm product markup | 0.01(1%) | ||

| Initial household product markup | 0.35(35%) | ||

| Market-related | Number of trading candidates on B2C market | 5 | |

| Number of trading candidates on labor market | 10 | ||

| Number of trading candidates on credit market | 3 | ||

| Number of trading candidates on deposit market | 3 | ||

| Interest-related | Initial interest rate on deposit | 0.0010(0.10%) | |

| Initial interest rate on loan | 0.0075(0.75%) | ||

| Interest rate on bond | 0.0025(0.25%) | ||

| Interest rate on short-term liquidity | 0.0050(0.50%) | ||

| Profit-related | Corporate tax rate, income tax rate | 0.18(18%) | |

| Dividend payout ratio for firms and banks | 0.90(90%) | ||

| Common behavior | Adaptive expectations parameters | 0.25 | |

| Normal distribution parameters | 0.0, 0.0094 | ||

| Firm behavior | Lower bound of desired production quantity | 240 | |

| Number of employees, adjust rate | 0.5 | ||

| Initial firm product markup | 0.01(1%) | ||

| Initial household product markup | 0.35(35%) | ||

| Amount of external financing | 1.0 | ||

| Bank behavior | Bank’s risk aversion | 3.0 | |

| Loan term | 20 steps | ||

| Estimated recovery rate | 0.0 | ||

| Household behavior | Propensity to consume out of income | 0.38581 | |

| Propensity to consume out of wealth | 0.25 | ||

| Periods of unemployment begin to reduce desired wage | 3 steps |

| Item | Households | Firms | Banks | Government | Central Bank | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deposit | 90,000 | 30,000 | −120,000 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Loan | 0 | −15,000 | 15,000 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Product inventory | 0 | 2694 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2694 |

| Material inventory | 0 | 36,418 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 36,418 |

| Bond | 0 | 0 | 80,000 | −110,000 | 30,000 | 0 |

| Reserve | 0 | 0 | 30,000 | 0 | −30,000 | 0 |

| Short-term liquidity | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Net wealth | 90,000 | 54,112 | 5000 | −110,000 | 0 | 39,112 |

| 1 | Dilaver et al. identified the strategy switching (SS) model as the fourth of the representative ACE models. The SS model is a general mechanism characterized by utilizing multiple types of agents with different expectation formation mechanisms; it is mainly used to analyze finances. However, it is not included in this volume because it is frequently used in financial markets to analyze investor behavior and financial asset prices. |

| 2 | The parameters of the supply chain networks’ degree distribution vary somewhat across regions, industries, and datasets studied. The authors of Perera et al. (2017) consulted 10 sources and reported that the parameters of the degree distribution of the corporate SCN ranged from 1.0 to 3.3, depending on the literature. Meanwhile, Fujiwara and Aoyama (2008) estimated the parameters of the cumulative degree distribution. The author of Newman (2005) found that the power-law exponent of the cumulative degree distribution is 1 less than the power-law exponent of the degree distribution, which is approximately 2.3 for the parameter of the degree distribution and which is within the range of values reported by Perera et al. Therefore, Fujiwara and Aoyama (2008)’s estimated parameters are considered to be of a general level. |

| 3 | According to the Basic Survey of Corporate Activities conducted by the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, the cost-to-income ratio of domestic firms has remained around 80% year after year. Note that 1.5 was chosen as the parameter that produces stable results when the model is run because the reciprocal of 1.5 is close to this level at around 67%. |

| 4 | According to the data from the Growth Strategy Subcommittee of the 2nd Industrial Structure Council organized by the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, the median markup ratio for Japanese firms is approximately 1.2, although it varies slightly by industry. In this model, each markup is set so that product prices for firms and households can be differentiated based on this level. |

| 5 | Based on statistical data for Japanese firms, the product turnover rate (annualized) is about 11.1 for the manufacturing sector, 19.9 for the wholesale sector, and 11.4 for the retail sector, giving an approximate average rate of 14 for all industries. The quarterly conversion is about 3.5, and taking the reciprocal of this value, the inventory ratio is about 0.28. Since there is no significant deviation from the estimates of Caiani et al. (2016), we use 0.10 as the inventory ratio in this model. |

| 6 | Around 2016, when Caiani et al. (2016) was published, Italy’s GDP growth rate was around 1%, and the ECB was easing its monetary policy by introducing negative interest rates. Japan also introduced negative interest rates in 2016 and continues to have a negative interest rate policy. As the economic situation is not significantly different from seven years ago, it is reasonable to refer to the setting of Caiani et al. (2016). |

| 7 | The number of industries is based on the number of industry categories used with the Japanese business statistics data, of which the model will be adapted to in the future. |

| 8 | The source of each indicator is as follows: the GDP is based on the data published by the Cabinet office; the CPI is based on the quarterly rate of change based on the data published by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications; and the unemployment rate is based on the Labour Force Survey published by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. |

References

- Brancaccio, Emiliano, Mauro Gallegati, and Raffaele Giammetti. 2021. Neoclassical influences in agent-based literature: A systematic review. Journal of Economic Surveys 36: 350–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caiani, Alessandro, Antoine Godin, and Stefano Lucarelli. 2014. Innovation and finance: A stock flow consistent analysis of great surges of development. Journal of Evolutionary Economics 24: 421–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caiani, Alessandro, Antoine Godin, Eugenio Caverzasi, Mauro Gallegati, Stephen Kinsella, and Joseph E. Stiglitz. 2016. Agent based-stock flow consistent macroeconomics: Towards a benchmark model. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 69: 375–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cincotti, Silvano, Marco Raberto, and Andrea Teglio. 2010. Credit Money and Macroeconomic Instability in the Agent-Based Model and Simulator Eurace. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1726782 (accessed on 29 April 2023).

- Cincotti, Silvano, Marco Raberto, and Andrea Teglio. 2012. Macroprudential policies in an agent-based artificial economy. Revue de l’OFCE 124: 205–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copeland, Morris A. 1949. Social Accounting for Moneyflows. The Accounting Review 24: 254–64. [Google Scholar]

- Dawid, Herbert, and Domenico Delli Gatti. 2018. Agent-Based Macroeconomics. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3112074 (accessed on 29 April 2023).

- Dawid, Herbert, and Philipp Harting. 2012. Capturing firm behavior in agent-based models of industry evolution and macroeconomic dynamics. In Evolution, Organization and Economic Behavior. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. [Google Scholar]

- Deissenberg, Christophe, Sander van der Hoog, and Herbert Dawid. 2008. Eurace: A massively parallel agentbased model of the european economy. Applied Mathematics and Computation 204: 541–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delli Gatti, Domenico, Corrado Di Guilmi, Edoardo Gaffeo, Gianfranco Giulioni, Mauro Gallegati, and Antonio Palestrini. 2005. A new approach to business uctuations. heterogeneous interacting agents, scaling laws and financial fragility. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 56: 489–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delli Gatti, Domenico, Mauro Gallegati, Bruce Greenwald, Alberto Russo, and Joseph E. Stiglitz. 2006. Business fluctuations in a credit-network economy. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and Its Applications 370: 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delli Gatti, Domenico, and Elisa Grugni. 2022. Breaking bad: Supply chain disruptions in a streamlined agent-based model. The European Journal of Finance 28: 1446–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delli Gatti, Domenico, and Severin Reissl. 2022. ABC: An Agent Based Exploration of the Macroeconomic Effects of COVID-19. Industrial and Corporate Change 2: 410–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Domenico, Lorenzo, Karolina Safarzynska, and Marco Raberto. 2022. Resource Scarcity, Circular Economy and the Energy Rebound: A Macro-Evolutionary Input-Output Model. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4266965 (accessed on 22 June 2023).

- Di Guilmi, Corrado. 2017. The agent-based approach to post Keynesian macro-modeling. Journal of Economic Surveys 31: 1183–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilaver, Özge, Robert Calvert Jump, and Paul Levine. 2018. Agent-based macroeconomics and dynamic stochastic general equilibrium models: Where do we go from here? Journal of Economic Surveys 32: 1134–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosi, Giovanni, Giorgio Fagiolo, and Andrea Roventini. 2006. An evolutionary model of endogenous business cycles. Computational Economics 27: 3–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosi, Giovanni, Giorgio Fagiolo, and Andrea Roventini. 2008. The microfoundations of business cycles: An evolutionary multi-agent model. Journal of Evolutionary Economics 18: 413–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosi, Giovanni, Giorgio Fagiolo, and Andrea Roventini. 2010. Schumpeter meeting Keynes: A policy-friendly model of endogenous growth and business cycle. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 34: 1748–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosi, Giovanni, Marcelo C. Pereira, Andrea Roventini, and Maria Enrica Virgillito. 2022. Technological paradigms, labour creation and destruction in a multi-sector agent-based model. Research Policy 51: 104565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, Yoshi, and Hideaki Aoyama. 2008. Large-scale structure of a nation-wide production network. The European Physical Journal B 77: 565–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godley, Wynne, and Marc Lavoie. 2007. Monetary Economics An Integrated Approach to Credit, Money, Income, Production and Wealth. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, Dabo, Daoping Wang, Stephane Hallegatte, Steven J. Davis, Jingwen Huo, Shuping Li, Yangchun Bai, Tianyang Lei, Qianyu Xue, D’Maris Coffman, and et al. 2020. Global supply-chain effects of COVID-19 control measures. Nature Human Behaviour 4: 577–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldane, Andrew, and Arthur Turrell. 2018. An interdisciplinary model for macroeconomics. Oxford Review of Economic Policy 34: 219–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, Robert, Sebastian Barnes, George Wharf, and Duncan MacDonald. 2021. A New Firm-Level Model of Corporate Sector Interactions and Fragility: The Corporate Agent-Based (CAB) Model. OECD Economics Department Working Papers 1675. Paris: OECD. [Google Scholar]

- Hodrick, Robert J., and Edward C. Prescott. 1997. Postwar U.S. Business Cycles: An Empirical Investigation. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 21: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, Hiroyasu. 2021. Propagation of International Supply-Chain Disruptions between Firms in a Country. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 14: 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, Hiroyasu, and Yasuyuki Todo. 2019. Firm-level propagation of shocks through supply-chain networks. Nature Sustainability 2: 841–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, Hiroyasu, and Yasuyuki Todo. 2020. The propagation of economic impacts through supply chains: The case of a mega-city lockdown to prevent the spread of COVID-19. PLoS ONE 15: e0239251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinsella, Stephen. Words to the Wise: Stock Flow Consistent Modeling of Financial Instability. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1955613 (accessed on 29 April 2023).

- Newman, Mark E. J. 2005. Power laws, Pareto distributions and Zipf’s law. Contemporary Physics 5: 323–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohno, Takashi, and Hiroshi Nishi. 2011. Reconstructing Kaleckian Model: Stock-Flow Consistent Model. Political Economy Quarterly 47: 6–18. (In Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- Otto, Christian, Sven N. Willner, Leonie Wenz, and Katja Frieler. 2017. Modeling loss-propagation in the global supply network: The dynamic agent-based model acclimate. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 83: 232–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, Supun, Michael G. H. Bell, and Michiel C. J. Bliemer. 2017. Network science approach to modelling the topology and robustness of supply chain networks: A review and perspective. Applied Network Science 2: 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichler, Anton, Marco Pangallo, R. Maria del Rio-Chanona, François Lafond, and J. Doyne Farmer. 2020. Production Networks and Epidemic Spreading: How to Restart the UK Economy? Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3606984 (accessed on 7 July 2023).

- Poledna, Sebastian, Michael Gregor Miess, Cars Hommes, and Katrin Rabitsch. 2023. Economic forecasting with an agent-based model. European Economic Review 151: 104306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, Towfique, Firouzeh Taghikhah, Sanjoy Kumar Paul, Nagesh Shukla, and Renu Agarwal. 2021. An agent-based model for supply chain recovery in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Computers and Industrial Engineering 158: 107401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reissl, Severin, Alessandro Caiani, Francesco Lamperti, Mattia Guerini, Fabio Vanni, Giorgio Fagiolo, Tommaso Ferraresi, Leonardo Ghezzi, Mauro Napoletano, and Andrea Roventini. 2022. Assessing the Economic Impact of Lockdowns in Italy: A Computational Input–Output Approach. Industrial and Corporate Change 31: 358–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Hoog, Sander, and Herbert Dawid. 2015. Bubbles, Crashes and the Financial Cycle Insights from a Stock-Flow Consistent Agent-Based Macroeconomic Model. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2616662 (accessed on 29 April 2023).

| Market | Demand Side | Supply Side |

|---|---|---|

| Business-to-business product market | Firms | Firms |

| Business-to-household product market | Households | Firms |

| Labor market | Firms, government | Households |

| Credit market | Firms | Banks |

| Deposit market | Firms, households | Banks |

| Market | Repetitions | Extracts | Sort by | Matching Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B2B market | 1 | 1 | – | All demand |

| B2C market | 10 | 5 | Lowest price | One at a time |

| Labor market | 100 | 10 | Lowest asking wage | All demand |

| Credit market | 10 | 3 | Lowest loan interest rate | All demand |

| Deposit market | 100 | 3 | Highest interest rate | All demand |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Obata, T.; Sakazaki, J.; Kurahashi, S. Building a Macroeconomic Simulator with Multi-Layered Supplier–Customer Relationships. Risks 2023, 11, 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks11070128

Obata T, Sakazaki J, Kurahashi S. Building a Macroeconomic Simulator with Multi-Layered Supplier–Customer Relationships. Risks. 2023; 11(7):128. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks11070128

Chicago/Turabian StyleObata, Takahiro, Jun Sakazaki, and Setsuya Kurahashi. 2023. "Building a Macroeconomic Simulator with Multi-Layered Supplier–Customer Relationships" Risks 11, no. 7: 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks11070128

APA StyleObata, T., Sakazaki, J., & Kurahashi, S. (2023). Building a Macroeconomic Simulator with Multi-Layered Supplier–Customer Relationships. Risks, 11(7), 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks11070128